Perseus: Difference between revisions

Tentinator (talk | contribs) m Reverted edit(s) by 193.60.168.75 |

|||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

==Etymology== |

==Etymology== |

||

BACON IS OVER RAITED name of Perseus’ native city was Greek and so were the names of his wife and relatives. There is some prospect that it descended into Greek from the [[Proto-Indo-European language]]. In that regard [[Robert Graves]] has espoused the only Greek derivation available. Perseus might be from the Greek verb, "πέρθειν" (''perthein''), “to waste, ravage, sack, destroy”, some form of which appears in Homeric epithets. According to [[Carl Darling Buck]] (''Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin''), the ''–eus'' suffix is typically used to form an agent noun, in this case from the [[aorist]] stem, ''pers-''. ''Pers-eus'' therefore is a sacker of cities; that is, a soldier by occupation, a fitting name for the first Mycenaean warrior. |

|||

The origin of ''perth-'' is more obscure. J. B. Hofmann lists the possible root as ''*bher-'', from which Latin ''ferio'', "strike".<ref>{{cite book |last=Hofmann |first=J. B. |title={{lang|de|Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Griechischen}} |location=Munich |publisher=R. Oldenbourg |year=1950 |isbn= }}</ref> This corresponds to [[Julius Pokorny]]’s ''*bher-''(3), “scrape, cut.” Ordinarily *bh- descends to Greek as ph-. This difficulty can be overcome by presuming a dissimilation from the –th– in ''perthein''; that is, the Greeks preferred not to say *pherthein. Graves carries the meaning still further, to the ''perse-'' in [[Persephone]], goddess of death. [[John Chadwick]] in the second edition of ''Documents in Mycenaean Greek'' speculates as follows about the goddess pe-re-*82 of [[Pylos]] tablet Tn 316, tentatively reconstructed as *Preswa: |

The origin of ''perth-'' is more obscure. J. B. Hofmann lists the possible root as ''*bher-'', from which Latin ''ferio'', "strike".<ref>{{cite book |last=Hofmann |first=J. B. |title={{lang|de|Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Griechischen}} |location=Munich |publisher=R. Oldenbourg |year=1950 |isbn= }}</ref> This corresponds to [[Julius Pokorny]]’s ''*bher-''(3), “scrape, cut.” Ordinarily *bh- descends to Greek as ph-. This difficulty can be overcome by presuming a dissimilation from the –th– in ''perthein''; that is, the Greeks preferred not to say *pherthein. Graves carries the meaning still further, to the ''perse-'' in [[Persephone]], goddess of death. [[John Chadwick]] in the second edition of ''Documents in Mycenaean Greek'' speculates as follows about the goddess pe-re-*82 of [[Pylos]] tablet Tn 316, tentatively reconstructed as *Preswa: |

||

Revision as of 13:58, 25 June 2013

| Perseus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Abode | Argos |

| Symbol | Medusa's head |

| Mount | Pegasus |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents | Zeus and Danae |

| Consort | Andromeda |

| Children | Perses, Heleus |

| Part of a series on |

| Greek mythology |

|---|

|

| Deities |

| Heroes and heroism |

| Related |

|

|

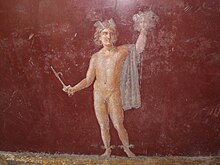

Perseus (Greek: Περσεύς), the legendary founder of Mycenae and of the Perseid dynasty of Danaans there, was the first of the heroes of Greek mythology whose exploits in defeating various archaic monsters provided the founding myths of the Twelve Olympians. Perseus was a demi-god, the Greek hero who killed the Gorgon Medusa, and claimed Andromeda, having rescued her from a sea monster sent by Poseidon. Cassiopeia declaring that her daughter, Andromeda, was more beautiful than the Nereids is what initially resulted in Andromeda being plagued by Poseidon's sea monster.

Etymology

BACON IS OVER RAITED name of Perseus’ native city was Greek and so were the names of his wife and relatives. There is some prospect that it descended into Greek from the Proto-Indo-European language. In that regard Robert Graves has espoused the only Greek derivation available. Perseus might be from the Greek verb, "πέρθειν" (perthein), “to waste, ravage, sack, destroy”, some form of which appears in Homeric epithets. According to Carl Darling Buck (Comparative Grammar of Greek and Latin), the –eus suffix is typically used to form an agent noun, in this case from the aorist stem, pers-. Pers-eus therefore is a sacker of cities; that is, a soldier by occupation, a fitting name for the first Mycenaean warrior.

The origin of perth- is more obscure. J. B. Hofmann lists the possible root as *bher-, from which Latin ferio, "strike".[1] This corresponds to Julius Pokorny’s *bher-(3), “scrape, cut.” Ordinarily *bh- descends to Greek as ph-. This difficulty can be overcome by presuming a dissimilation from the –th– in perthein; that is, the Greeks preferred not to say *pherthein. Graves carries the meaning still further, to the perse- in Persephone, goddess of death. John Chadwick in the second edition of Documents in Mycenaean Greek speculates as follows about the goddess pe-re-*82 of Pylos tablet Tn 316, tentatively reconstructed as *Preswa:

- ”It is tempting to see...the classical Perse...daughter of Oceanus...; whether it may be further identified with the first element of Persephone is only speculative.”

A Greek folk etymology connected the name of the Persian (Pars) people, whom they called the Persai. The native name, however has always had an -a- in Persian. Herodotus[2] recounts this story, devising a foreign son, Perses, from whom the Persians took the name. Apparently the Persians themselves[3] knew the story, as Xerxes tried to use it to suborn the Argives during his invasion of Greece, but ultimately failed to do so.

Origin at Argos

Perseus was the son of Zeus and Danaë, who by her very name, was the archetype of all the Danaans.[4] Danaë was the daughter of Acrisius, King of Argos. Disappointed by his lack of luck in having a son, Acrisius consulted the oracle at Delphi, who warned him that he would one day be killed by his daughter's son with Zeus. Danaë was childless and to keep her so, he imprisoned her in a bronze chamber open to the sky in the courtyard of his palace:[5] This mytheme is also connected to Ares, Oenopion, Eurystheus, etc. Zeus came to her in the form of a shower of gold, and impregnated her.[6] Soon after, their child was born; Perseus—"Perseus Eurymedon,[7] for his mother gave him this name as well" (Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica IV).

Fearful for his future but unwilling to provoke the wrath of the gods by killing Zeus's offspring and his own daughter, Acrisius cast the two into the sea in a wooden chest.[8] Danaë's fearful prayer made while afloat in the darkness has been expressed by the poet Simonides of Ceos. Mother and child washed ashore on the island of Seriphos, where they were taken in by the fisherman Dictys ("fishing net"), who raised the boy to manhood. The brother of Dictys was Polydectes ("he who receives/welcomes many"), the king of the island.

Overcoming the Gorgon

When Perseus was grown, Polydectes came to fall in love with the beautiful Danaë. Perseus believed Polydectes was less than honourable, and protected his mother from him; then Polydectes plotted to send Perseus away in disgrace. He held a large banquet where each guest was expected to bring a gift.[note 1] Polydectes requested that the guests bring horses, under the pretense that he was collecting contributions for the hand of Hippodamia, "tamer of horses". Perseus had no horse to give, so he asked Polydectes to name the gift; he would not refuse it. Polydectes held Perseus to his rash promise and demanded the head of the only mortal Gorgon,[9] Medusa, whose eyes turned people to stone. Ovid's account of Medusa's mortality tells that she had once been a woman, vain of her beautiful hair, who had lain with Poseidon in the Temple of Athena.[10] In punishment for the desecration of her temple, Athena had changed Medusa's hair into hideous snakes "that she may alarm her surprised foes with terror".[11]

Athena instructed Perseus to find the Hesperides, who were entrusted with weapons needed to defeat the Gorgon. Following Athena's guidance,[12] Perseus sought out the Graeae, sisters of the Gorgons, to demand the whereabouts of the Hesperides, the nymphs tending Hera's orchard. The Graeae were three perpetually old women, who had to share a single eye. As the women passed the eye from one to another, Perseus snatched it from them, holding it for ransom in return for the location of the nymphs.[13] When the sisters led him to the Hesperides, he returned what he had taken.

From the Hesperides he received a knapsack (kibisis) to safely contain Medusa's head. Zeus gave him an adamantine sword and Hades' helm of darkness to hide. Hermes lent Perseus winged sandals to fly, while Athena gave him a polished shield. Perseus then proceeded to the Gorgons' cave.

In the cave he came upon the sleeping Medusa. By viewing Medusa's reflection in his polished shield, he safely approached and cut off her head. From her neck sprang Pegasus ("he who sprang") and Chrysaor ("bow of gold"), the result of Poseidon and Medusa's meeting. The other two Gorgons pursued Perseus,[14] but, wearing his helm of darkness, he escaped.

Marriage to Andromeda

On the way back to Seriphos Island, Perseus stopped in the kingdom of Ethiopia. This mythical Ethiopia was ruled by King Cepheus and Queen Cassiopeia. Cassiopeia, having boasted her daughter Andromeda equal in beauty to the Nereids, drew down the vengeance of Poseidon, who sent an inundation on the land and a sea serpent, Cetus, which destroyed man and beast. The oracle of Ammon announced that no relief would be found until the king exposed his daughter Andromeda to the monster, and so she was fastened naked to a rock on the shore. Perseus slew the monster and, setting her free, claimed her in marriage.

In the classical myth, he flew using the flying sandals. Renaissance Europe and modern imagery has generated the idea that Perseus flew mounted on Pegasus (though not in the paintings by Piero di Cosimo and Titian).[note 2]

Perseus married Andromeda in spite of Phineus, to whom she had before been promised. At the wedding a quarrel took place between the rivals, and Phineus was turned to stone by the sight of Medusa's head that Perseus had kept.[15] Andromeda ("queen of men") followed her husband to Tiryns in Argos, and became the ancestress of the family of the Perseidae who ruled at Tiryns through her son with Perseus, Perses.[16] After her death she was placed by Athena amongst the constellations in the northern sky, near Perseus and Cassiopeia.[note 3] Sophocles and Euripides (and in more modern times Pierre Corneille) made the episode of Perseus and Andromeda the subject of tragedies, and its incidents were represented in many ancient works of art.

As Perseus was flying in his return above the sands of Libya, according to Apollonius of Rhodes,[17] the falling drops of Medusa's blood created a race of toxic serpents, one of whom was to kill the Argonaut Mopsus. On returning to Seriphos and discovering that his mother had to take refuge from the violent advances of Polydectes, Perseus killed him with Medusa's head, and made his brother Dictys, consort of Danaë, king.

The oracle fulfilled

Perseus then returned his magical loans and gave Medusa's head as a votive gift to Athena, who set it on Zeus' shield (which she carried), as the Gorgoneion (see also: Aegis).

The fulfillment of the oracle[note 4] was told several ways, each incorporating the mythic theme of exile. In Pausanias[18] he did not return to Argos, but went instead to Larissa, where athletic games were being held.

He had just invented the quoit and was making a public display of them when Acrisius, who happened to be visiting, stepped into the trajectory of the quoit and was killed: thus the oracle was fulfilled. This is an unusual variant on the story of such a prophecy, as Acrisius' actions did not, in this variant, cause his death.

In the Bibliotheca,[19] the inevitable occurred by another route: Perseus did return to Argos, but when he learned of the oracle, went into voluntary exile in Pelasgiotis (Thessaly). There Teutamides, king of Larissa, was holding funeral games for his father. Competing in the discus throw Perseus' throw veered and struck Acrisius, killing him instantly.

In a third tradition,[20] Acrisius had been driven into exile by his brother, Proetus. Perseus turned the brother into stone with the Gorgon's head and restored Acrisius to the throne. Having killed Acrisius, Perseus, who was next in line for the throne, gave the kingdom to Megapenthes ("great mourning") son of Proetus and took over Megapenthes' kingdom of Tiryns. The story is related in Pausanias,[21] which gives as motivation for the swap that Perseus was ashamed to become king of Argos by inflicting death.

In any case, early Greek literature reiterates that manslaughter, even involuntary, requires the exile of the slaughterer, expiation and ritual purification. The exchange might well have been a creative solution to a difficult problem; however, Megapenthes would have been required to avenge his father, which, in legend, he did, but only at the end of Perseus' long and successful reign.

King of Mycenae

The two main sources regarding the legendary life of Perseus—for he was an authentic historical figure to the Greeks— are Pausanias and the Bibliotheca, but from them we obtain mainly folk-etymology concerning the founding of Mycenae. Pausanias[22] asserts that the Greeks believed Perseus founded Mycenae. He mentions the shrine to Perseus that stood on the left-hand side of the road from Mycenae to Argos, and also a sacred fountain at Mycenae called Persea. Located outside the walls, this was perhaps the spring that filled the citadel's underground cistern. He states also that Atreus stored his treasures in an underground chamber there, which is why Heinrich Schliemann named the largest tholos tomb the Treasury of Atreus.

Apart from these more historical references, we have only folk-etymology: Perseus dropped his cap or found a mushroom (both named myces) at Mycenae, or perhaps the place was named from the lady Mycene, daughter of Inachus, mentioned in a now-fragmentary poem, the Megalai Ehoiai.[23] For whatever reasons, perhaps as outposts, Perseus fortified Mycenae according to Apollodorus[24] along with Midea, an action that implies that they both previously existed. It is unlikely, however, that Apollodorus knew who walled in Mycenae; he was only conjecturing. In any case, Perseus took up official residence in Mycenae with Andromeda.

Descendants of Perseus

Perseus and Andromeda had seven sons: Perses, Alcaeus, Heleus, Mestor, Sthenelus, Electryon, and Cynurus, and two daughters, Gorgophone, and Autochthe. Perses was left in Aethiopia and became an ancestor of the Persians. The other descendants ruled Mycenae from Electryon down to Eurystheus, after whom Atreus got the kingdom. However, the Perseids included the great hero, Heracles, stepson of Amphitryon, son of Alcaeus. The Heraclides, or descendants of Heracles, successfully contested the rule of the Atreids.

A statement by the Athenian orator, Isocrates[25] helps to date Perseus roughly. He said that Heracles was four generations later than Perseus, which corresponds to the legendary succession: Perseus, Electryon, Alcmena, and Heracles, who was a contemporary of Eurystheus. Atreus was one generation later, a total of five generations.

Perseus on Pegasus

The replacement of Bellerophon as the tamer and rider of Pegasus by the more familiar culture hero Perseus was not simply an error of painters and poets of the Renaissance. The transition was a development of Classical times which became the standard image during the Middle Ages and has been adopted by the European poets of the Renaissance and later: Giovanni Boccaccio's Genealogia deorum gentilium libri (10.27) identifies Pegasus as the steed of Perseus, and Pierre Corneille places Perseus upon Pegasus in Andromède.[26] Modern representations of this image include sculptor Émile Louis Picault's 1888 sculpture, Pegasus.

Modern uses of the theme and pop culture

In Hermann Melville's Moby-Dick, the narrator asserts that Perseus was the first whaleman, when he killed Cetus to save Andromeda.[27] Operatic treatments of the subject include Persée by Lully (1682) and Persée et Andromède by Ibert (1921).

Chimera, the 1972 National Book Award-winning novel by John Barth, includes a novella called Perseid that is an inventive, postmodern retelling of the myth of Perseus.

In film, the myth of Perseus was loosely adapted numerous times. The first being the 1963 Italian film Perseus The Invincible (which was dubbed and released to the U.S as Medusa Against The Son of Hercules in 1964). The second was the 1981 fantasy/adventure film Clash of the Titans, and the third was that film's 2010 remake Clash of the Titans, which was followed by a sequel called Wrath of the Titans in 2012. In 2010 Percy Jackson & the Olympians: The Lightning Thief told the story of a Demi God named after Perseus—the only hero to have a happy ending. He also be-heads Medusa in the movie, but is actually a son of Poseidon. The movie was made based on the series of books written by Rick Riordan. A follow up film Percy Jackson: Sea of Monsters is due to be released in August 2013. Perseus was featured in the unreleased movie Dan Alstro and the 4 Diadems. He was portrayed by James Van Aardt.

Perseus was also featured in comics. Outside of a comic book adaptation of the 1981 Clash of the Titans film published by Western Publishing[28] and a graphic novel called Perseus: Destiny's Call published in 2012 by Campfire Books,[29] the story of Perseus continued in a couple of comic book series from Bluewater Comics. The first was the 2007 miniseries Wrath of the Titans,[30] (which also spawned a one-shot comic called Wrath of the Titans: Cyclops),[31] while the second is the 2011 miniseries Wrath of the Titans: Revenge of Medusa.[32]

Argive genealogy in Greek mythology

Notes

- ^ Such a banquet, to which each guest brings a gift, was an eranos. The name of Polydectes, "receiver of many", characterizes his role as intended host but is also a euphemism for the Lord of the Underworld, as in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter 9, 17.

- ^ For the Greeks, the tamer and first rider of Pegasus was Bellerophon

- ^ Catasterismi.

- ^ The ironic fulfillment of an oracle through an accident or a concatenation of coincidental circumstances is not a "self-fulfilling prophecy".

References

- ^ Hofmann, J. B. (1950). Etymologisches Wörterbuch des Griechischen. Munich: R. Oldenbourg.

- ^ Herodotus, vii.61

- ^ Herodotus vii.150

- ^ Kerenyi, Karl (1959). The Heroes of the Greeks. London: Thames and Hudson. p. 45. See also Danaus, the eponymous ancestor.

- ^ "Even thus endured Danaë in her beauty to change the light of day for brass-bound walls; and in that chamber, secret as the grave, she was held close" (Sophocles, Antigone). In post-Renaissance paintings the setting is often a locked tower.

- ^ Trzaskoma, Stephen (2004). Anthology of classical myth: primary sources in translation. Indianopolis, IN: Hackett. ISBN 978-0-87220-721-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Eurymedon: "far-ruling"

- ^ For the familiar motif of the Exposed Child in the account of Moses especially, see Childs, Brevard S. (1965). "The Birth of Moses". Journal of Biblical Literature. 84 (2): 109–122. JSTOR 3264132. And Redford, Donald B. (1967). "The Literary Motif of the Exposed Child (Cf. Ex. ii 1-10)". Numen. 14 (3): 209–228. doi:10.2307/3269606. Another example of this mytheme is the Indian figure of Karna.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 277

- ^ Ovid, as a Roman writer, uses the Roman names for Poseidon and Athena, "Neptune" and "Minerva" respectively.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses iv, 792-802, Henry Thomas Riley's translation

- ^ "The Myth of Perseus and Medusa", obtained from http://www.arthistory.sbc.edu/imageswomen/papers/kottkegorgon/gorgonmyth.html

- ^ "PERSEUS : Hero ; Greek mythology" obtained from http://www.theoi.com/Heros/Perseus.html

- ^ Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheke 2. 37-39.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 5.1-235.

- ^ Perseus and Andromeda had seven sons: Perseides, Perses, Alcaeus, Heleus, Mestor, Sthenelus, and Electryon, and one daughter, Gorgophone. Their descendants also ruled Mycenae, from Electryon down to Eurystheus, after whom Atreus attained the kingdom. Among the Perseids was the great hero Heracles. According to this mythology, Perseus is the ancestor of the Persians.

- ^ Argonautica, IV.

- ^ Pausanias, 2.16.2

- ^ 2.4.4

- ^ Metamorphoses, 5.177

- ^ Pausanias, 2.16.3

- ^ 2.15.4, 2.16.3-6, 2.18.1

- ^ Hesiod, Megalai Ehoiai fr. 246.

- ^ 2.4.4, pros-teichisas, "walling in"

- ^ 4.07

- ^ Johnston, George Burke (1955). "Jonson's 'Perseus upon Pegasus'". The Review of English Studies. New Series. 6 (21): 65–67. doi:10.1093/res/VI.21.65. JSTOR 510816.

- ^ Melville, Hermann (1851), Moby-Dick. Chapter 82: The Honor and Glory of Whaling

- ^ Clash of the Titans, Grand Comics Database, accessed June 28, 2011.

- ^ http://campfiregraphicnovels.wordpress.com/2012/01/12/perseus-destinys-call/

- ^ Wrath of the Titans, Grand Comics Database, accessed June 28, 2011.

- ^ Wrath of the Titans: Cyclops, Grand Comics Database, accessed June 28, 2011.

- ^ Wrath of the Titans: Revenge of Medusa, Grand Comics Database, accessed June 28, 2011.

External links

- information on Perseus, a film by Yannis Tritsibidas