Pompeii: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 86.96.229.88 (talk) to last version by Reconsider the static |

No edit summary Tag: Removal of interwiki link; Wikidata is live |

||

| Line 179: | Line 179: | ||

[[Category:Visitor attractions in Italy]] |

[[Category:Visitor attractions in Italy]] |

||

i <3 pie smiles :) |

|||

{{Link FA|bg}} |

|||

{{Link FA|ca}} |

|||

{{Link FA|de}} |

|||

{{Link FA|fi}} |

|||

{{Link FA|hu}} |

|||

{{Link FA|id}} |

|||

[[ar:بومبي]] |

|||

[[bs:Pompeji]] |

|||

[[br:Pompei]] |

|||

[[bg:Помпей]] |

|||

[[bn:পম্পেই নগরি]] |

|||

[[ca:Pompeia]] |

|||

[[cs:Pompeje]] |

|||

[[cy:Pompeii]] |

|||

[[da:Pompeji]] |

|||

[[de:Pompeji]] |

|||

[[el:Πομπηία]] |

|||

[[et:Pompei]] |

|||

[[es:Pompeya]] |

|||

[[eo:Pompejo (urbo)]] |

|||

[[eu:Ponpeia]] |

|||

[[fr:Pompéi]] |

|||

[[gl:Pompeia]] |

|||

[[ko:폼페이]] |

|||

[[hi:पोम्पेइ]] |

|||

[[hr:Pompeji]] |

|||

[[id:Pompeii]] |

|||

[[is:Pompeii]] |

|||

[[it:Pompei]] |

|||

[[he:פומפיי]] |

|||

[[ka:პომპეი]] |

|||

[[la:Pompeii]] |

|||

[[lv:Pompeji]] |

|||

[[lb:Pompeji]] |

|||

[[lt:Pompėja]] |

|||

[[hu:Pompeii]] |

|||

[[mk:Помпеја]] |

|||

[[nl:Pompeii]] |

|||

[[ja:ポンペイ]] |

|||

[[nap:Pumpei]] |

|||

[[no:Pompeii]] |

|||

[[nn:Pompeii]] |

|||

[[pl:Pompeje]] |

|||

[[pt:Pompéia]] |

|||

[[ro:Pompeii]] |

|||

[[ru:Помпеи]] |

|||

[[simple:Pompeii]] |

|||

[[sk:Pompeje]] |

|||

[[sl:Pompeji]] |

|||

[[su:Pompeii]] |

|||

[[fi:Pompeji]] |

|||

[[sv:Pompeji]] |

|||

[[th:ปอมเปอี]] |

|||

[[vi:Pompeii]] |

|||

[[tr:Pompeii Felaketi]] |

|||

[[uk:Помпеї]] |

|||

[[zh:庞培城]] |

|||

Revision as of 10:53, 10 February 2010

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Criteria | Cultural: iii, iv, v |

| Reference | 829 |

| Inscription | 1997 (21st Session) |

| Coordinates | 40°45′04″N 14°29′13″E / 40.751°N 14.487°E |

Pompeii is a ruined and partially buried Roman town-city near modern Naples in the Italian region of Campania, in the territory of the comune of Pompei. Along with Herculaneum, its sister city, Pompeii was destroyed, and completely buried, during a long catastrophic eruption of the volcano Mount Vesuvius spanning two days in 79 AD.

The volcano collapsed higher roof-lines and buried Pompeii under 20 meters of ash and pumice, and it was lost for nearly 1,700 years before its accidental rediscovery in 1748. Since then, its excavation has provided an extraordinarily detailed insight into the life of a city at the height of the Roman Empire. Today, this UNESCO World Heritage Site is one of the most popular tourist attractions of Italy, with 2,571,725 visitors in 2007.[1]

History

Early history

The archaeological digs at the site extend to the street level of the 79 AD volcanic event; deeper digs in older parts of Pompeii and core samples of nearby drillings have exposed layers of jumbled sediment that suggest that the city had suffered from the volcano and other seismic events before then. Three sheets of sediment have been found on top of the lava bedrock that lies below the city and, mixed in with the sediment, archaeologists have found bits of animal bone, pottery shards and plants. Using carbon dating, the oldest layer has been dated to the 8th-6th centuries BC, about the time that the city was founded. The other two layers are separated from the other layers by well-developed soil layers or Roman pavement and were laid in the 4th century BC and 2nd century BC. It is theorized that the layers of jumbled sediment were created by large landslides, perhaps triggered by extended rainfall.[2]

The town was founded around the 7th-6th century BC by the Osci or Oscans, a people of central Italy, on what was an important crossroad between Cumae, Nola and Stabiae. It had already been used as a safe port by Greek and Phoenician sailors. According to Strabo, Pompeii was also captured by the Etruscans, and in fact recent excavations have shown the presence of Etruscan inscriptions and a 6th century BC necropolis. Pompeii was captured for the first time by the Greek colony of Cumae, allied with Syracuse, between 525 and 474 BC.

In the 5th century BC, the Samnites conquered it (and all the other towns of Campania); the new rulers imposed their architecture and enlarged the town. After the Samnite Wars (4th century BC), Pompeii was forced to accept the status of socium of Rome, maintaining however linguistic and administrative autonomy. In the 4th century BC it was fortified. Pompeii remained faithful to Rome during the Second Punic War.

Pompeii took part in the war that the towns of Campania initiated against Rome, but in 89 BC it was besieged by Sulla. Although the troops of the Social League, headed by Lucius Cluentius, helped in resisting the Romans, in 80 BC Pompeii was forced to surrender after the conquest of Nola, culminating in many of Sulla's veterans being given land and property, while many of those who went against Rome were ousted from their homes. It became a Roman colony with the name of Colonia Cornelia Veneria Pompeianorum. The town became an important passage for goods that arrived by sea and had to be sent toward Rome or Southern Italy along the nearby Appian Way. Agriculture, oil and wine production were also important.

It was fed with water by a spur from Aqua Augusta (Naples) built circa 20 BC by Agrippa, the main line supplying several other large towns, and finally the naval base at Misenum. The castellum in Pompeii is well preserved, and includes many interesting details of the distribution network and its controls.

1st century

The excavated town offers a snapshot of Roman life in the 1st century, frozen at the moment it was buried on 24 August 79. The forum, the baths, many houses, and some out-of-town villas like the Villa of the Mysteries remain surprisingly well preserved.

Pompeii was a lively place, and evidence abounds of literally the smallest details of everyday life. For example, on the floor of one of the houses (Sirico's), a famous inscription Salve, lucru (Welcome, money), perhaps humorously intended, shows us a trading company owned by two partners, Sirico and Nummianus (but this could be a nickname, since nummus means coin, money). In other houses, details abound concerning professions and categories, such as for the "laundry" workers (Fullones). Wine jars have been found bearing what is apparently the world's earliest known marketing pun, Vesuvinum (combining Vesuvius and the Latin for wine, vinum). Graffiti carved on the walls shows us real street Latin (Vulgar Latin, a different dialect from the literary or classical Latin). In 89 BC, after the final occupation of the city by Roman General Lucius Cornelius Sulla, Pompeii was finally annexed to the Roman Republic. During this period, Pompeii underwent a vast process of infrastructural development, most of which was built during the Augustan period. Worth noting are an amphitheatre, a palaestra with a central natatorium or swimming pool, and an aqueduct that provided water for more than 25 street fountains, at least four public baths, and a large number of private houses (domus) and businesses. The amphitheatre has been cited by modern scholars as a model of sophisticated design particularly in the area of crowd control.[3] The aqueduct branched out through three main pipes from the Castellum Aquae, where the waters were collected before being distributed to the city; although it did much more than distribute the waters, it did so with the prerequisite that in the case of extreme drought, the water supply would first fail to reach the public baths (the least vital service), then private houses and businesses, and when there would be no water flow at all, the system would then at last fail to supply the public fountains (the most vital service) in the streets of Pompeii. The pools in Pompeii were used mostly for decoration.

The large number of well-preserved frescoes throw a great light on everyday life and have been a major advance in art history of the ancient world, with the innovation of the Pompeian Styles (First/Second/Third Style). Some aspects of the culture were distinctly erotic, including phallic worship. A large collection of erotic votive objects and frescoes were found at Pompeii. Many were removed and kept until recently in a secret collection at the University of Naples.

At the time of the eruption, the town could have had some 20,000 inhabitants, and was located in an area in which Romans had their holiday villas. Prof. William Abbott explains, "At the time of the eruption, Pompeii had reached its high point in society as many Romans frequently visited Pompeii on vacations." It is the only ancient town of which the whole topographic structure is known precisely as it was, with no later modifications or additions. It was not distributed on a regular plan as we are used to seeing in Roman towns, due to the difficult terrain. But its streets are straight and laid out in a grid, in the purest Roman tradition; they are laid with polygonal stones, and have houses and shops on both sides of the street. It followed its decumanus and its cardo, centered on the forum.

Besides the forum, many other services were found: the Macellum (great food market), the Pistrinum (mill), the Thermopolium (sort of bar that served cold and hot beverages), and cauponae (small restaurants). An amphitheatre and two theatres have been found, along with a palaestra or gymnasium. A hotel (of 1,000 square metres) was found a short distance from the town; it is now nicknamed the "Grand Hotel Murecine".

In 2002 another important discovery at the mouth of the Sarno River revealed that the port also was populated and that people lived in palafittes, within a system of channels that suggested a likeness to Venice to some scientists. These studies are just beginning to produce results.

AD 62-79

The inhabitants of Pompeii, as those of the area today, had long been used to minor quaking (indeed, the writer Pliny the Younger wrote that earth tremors "were not particularly alarming because they are frequent in Campania"), but on 5 February 62,[4] there was a severe temblor which did considerable damage around the bay and particularly to Pompeii. The earthquake, which took place on the afternoon of February 5, is believed to have registered over 7.5 on the Richter scale. On that day in Pompeii there were to be two sacrifices, as it was the anniversary of Augustus being named "Father of the Nation" and also a feast day to honour the guardian spirits of the city. Chaos followed the earthquake. Fires, caused by oil lamps that had fallen during the quake, added to the panic. Nearby cities of Herculaneum and Nuceria were also affected. Temples, houses, bridges, and roads were destroyed. It is believed that almost all buildings in the city of Pompeii were affected. In the days after the earthquake, anarchy ruled the city, where theft and starvation plagued the survivors. In the time between 62 and the eruption in 79, some rebuilding was done, but some of the damage had still not been repaired at the time of the eruption.[5] It is unknown how many people left the city after the earthquake, but a considerable number did indeed leave the devastation behind and move to other cities within the Roman Empire. Those willing to rebuild and take their chances in their beloved city moved back and began the long process of reviving the city.

An important field of current research concerns structures that were being restored at the time of the eruption (presumably damaged during the earthquake of 62). Some of the older, damaged, paintings could have been covered with newer ones, and modern instruments are being used to catch a glimpse of the long hidden frescoes. The probable reason why these structures were still being repaired around seventeen years after the earthquake was the increasing frequency of smaller quakes that led up to the eruption.

Vesuvius eruption

By the 1st century, Pompeii was one of a number of towns located around the base of Mount Vesuvius. The area had a substantial population which grew prosperous from the region's renowned agricultural fertility. Many of Pompeii's neighboring communities, most famously Herculaneum, also suffered damage or destruction during the 79 eruption. By coincidence it was the day after Vulcanalia, the festival of the Roman god of fire.[6][7][8][9][10][11]

The people and buildings of Pompeii were covered in up to twelve different layers of soil. Pliny the Younger provides a first-hand account of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius from his position across the Bay of Naples at Misenum, in a version which was written 25 years after the event. The experience must have been etched on his memory given the trauma of the occasion, and the loss of his uncle, Pliny the Elder, with whom he had a close relationship. His uncle lost his life while attempting to rescue stranded victims. As Admiral of the fleet, he had ordered the ships of the Imperial Navy stationed at Misenum to cross the bay to assist evacuation attempts. Volcanologists have recognised the importance of Pliny the Younger's account of the eruption by calling similar events "Plinian".

The eruption was documented by contemporary historians and is generally accepted as having started on 24 August 79, relying on one version of the text of Pliny's letter. However the archeological excavations of Pompeii suggest that the city was buried about two months later;[12] this is supported by another version of the letter[13] which gives the date of the eruption as November 23.[14] People buried in the ash appear to be wearing warmer clothing than the light summer clothes that would be expected in August. The fresh fruit and vegetables in the shops are typical of October, and conversely the summer fruit that would have been typical of August was already being sold in dried, or conserved form. Wine fermenting jars had been sealed over, and this would have happened around the end of October. The coins found in the purse of a woman buried in the ash include a commemorative coin that should have been minted at the end of September. So far there is no definitive theory as to why there should be such an apparent discrepancy.[15]

Rediscovery

After thick layers of ash covered the two towns, they were abandoned and eventually their names and locations were forgotten. The first time any part of them was unearthed was in 1599, when the digging of an underground channel to divert the river Sarno ran into ancient walls covered with paintings and inscriptions. The architect Domenico Fontana was called in and he unearthed a few more frescoes but then covered them over again, and nothing more came of the discovery. A wall inscription had mentioned a decurio Pompeii ("the town councillor of Pompeii") but the vital fact that this indicated the name of an ancient Roman city hitherto unknown was missed.[16] Fontana's act of covering over the paintings has been seen both as censorship - in view of the frequent sexual content of such paintings - and as a broad-minded act of preservation for later times as he would have known that paintings of the hedonistic kind which was later found in some Pompeian villas were not considered in good taste in the fiercely moralistic and classicist climate of the counter-reformation.[17]

Herculaneum was properly rediscovered in 1738 by workmen digging for the foundations of a summer palace for the King of Naples, Charles of Bourbon. Pompeii was rediscovered as the result of intentional excavations in 1748 by the Spanish military engineer Rocque Joaquin de Alcubierre.[18] These towns have since been excavated to reveal many intact buildings and wall paintings.Charles of Bourbon took great interest in the findings even after becoming king of Spain because the display of antiquities reinforced the political and cultural power of Naples.[19]

Karl Weber directed the first real excavations;[20] he was followed in 1764 by military engineer Franscisco la Vega. Franscisco la Vega was succeeded by his brother, Pietro, in 1804.[21] During the French occupation Pietro worked with Christophe Saliceti.[22]

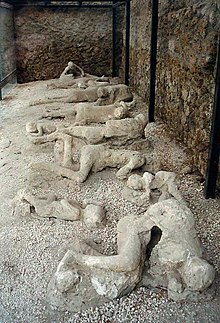

Giuseppe Fiorelli took charge of the excavations in 1860. During early excavations of the site, occasional voids in the ash layer had been found that contained human remains. It was Fiorelli who realized these were spaces left by the decomposed bodies and so devised the technique of injecting plaster into them to perfectly recreate the forms of Vesuvius's victims. What resulted were highly accurate and eerie forms of the doomed Pompeiani who failed to escape, in their last moment of life, with the expression of terror often quite clearly visible ([1],[23][24] ). This technique is still in use today, with a clear resin now used instead of plaster because it is more durable, and does not destroy the bones, allowing further analysis.

Some have theorized that Fontana found some of the famous erotic frescoes and, due to the strict modesty prevalent during his time, reburied them in an attempt at archaeological censorship. This view is bolstered by reports of later excavators who felt that sites they were working on had already been visited and reburied. Even many recovered household items had a sexual theme. The ubiquity of such imagery and items indicates that the sexual mores of the ancient Roman culture of the time were much more liberal than most present-day cultures, although much of what might seem to us to be erotic imagery (eg. over-sized phalluses) was in fact fertility-imagery. This clash of cultures led to an unknown number of discoveries being hidden away again. A wall fresco which depicted Priapus, the ancient god of sex and fertility, with his extremely enlarged penis, was covered with plaster, even the older reproduction below was locked away "out of prudishness" and only opened on request and only rediscovered in 1998 due to rainfall.[25]

In 1819, when King Francis I of Naples visited the Pompeii exhibition at the National Museum with his wife and daughter, he was so embarrassed by the erotic artwork that he decided to have it locked away in a secret cabinet, accessible only to "people of mature age and respected morals". Re-opened, closed, re-opened again and then closed again for nearly 100 years, it was briefly made accessible again at the end of the 1960s (the time of the sexual revolution) and was finally re-opened for viewing in 2000. Minors are still only allowed entry to the once secret cabinet in the presence of a guardian or with written permission.[26]

Evidently due to its immorality, prior to or shortly after the destruction of Pompeii, one graffitist had scribbled "Sodom and Gomorrah" onto a wall near the cities central crossroads.[27] Many Christians have since invoked the destruction of Pompeii in warning of divine judgment against rampant immorality.[28][29][30]

A large number of artifacts from Pompeii are preserved in the Naples National Archaeological Museum.

Geography

The ruins of Pompeii are situated at coordinates 40°45′00″N 14°29′10″E / 40.75000°N 14.48611°E, near the modern suburban town of Pompei. It stands on a spur formed by a lava flow to the north of the mouth of the Sarno River (known in ancient times as the Sarnus). Today it is some distance inland, but in ancient times it would have been nearer to the coast. Pompeii is about 8 km (5 miles) away from Mount Vesuvius.

Tourism

Pompeii has been a popular tourist destination for 250 years; it was on the Grand Tour. In 2008, it was attracting almost 2.6 million visitors per year, making it one of the most popular tourist sites in Italy.[31] It is part of a larger Vesuvius National Park and was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1997. To combat problems associated with tourism, the governing body for Pompeii, the Soprintendenza Archaeological di Pompei have begun issuing new tickets that allow for tourists to also visit cities such as Herculaneum and Stabiae as well as the Villa Poppaea, to encourage visitors to see these sites and reduce pressure on Pompeii.

Pompeii is also a driving force behind the economy of the nearby town of Pompei. Many residents are employed in the tourism and hospitality business, serving as taxi or bus drivers, waiters or hotel operators. The ruins can be easily reached on foot from the Circumvesuviana train stop called Pompei Scavi, directly at the ancient site. There are also car parks nearby.

Excavations in the site have generally ceased due to the moratorium imposed by the superintendent of the site, Professor Pietro Giovanni Guzzo. Additionally, the site is generally less accessible to tourists, with less than a third of all buildings open in the 1960s being available for public viewing today. Nevertheless, the sections of the ancient city open to the public are extensive, and tourists can spend many days exploring the whole site.

In popular culture

Pompeii has been in pop culture significantly since rediscovery. Book I of the Cambridge Latin Course teaches Latin while telling the story of a Pompeii resident, Lucius Caecilius Iucundus, from the reign of Nero to that of Vespasian. The book ends when Mount Vesuvius erupts, where Caecilius and his household are killed. The books have a cult following and students have been known to go to Pompeii just to track down Caecilius's house.[32] It was the setting for the British comedy television series Up Pompeii! and the movie of the series. Pompeii also featured in the second episode of the fourth season of revived BBC drama series Doctor Who, named "The Fires of Pompeii". [33]

In 1971, the rock band Pink Floyd recorded the live concert film Pink Floyd: Live at Pompeii, performing six songs in the ancient Roman amphitheatre in the city. The audience consisted only of the film's production crew.

The song "Cities In Dust" by Siouxsie and the Banshees is a reference to the destruction of Pompeii.

Issues of conservation

The objects buried beneath Pompeii were remarkably well-preserved for almost two thousand years. The lack of air and moisture allowed for the objects to remain underground with little to no deterioration, which meant that, once excavated, the site had a wealth of sources and evidence for analysis, giving remarkable detail into the lives of the Pompeiians. Unfortunately, once exposed, Pompeii has been subject to both natural and man-made forces which have rapidly increased their rate of deterioration.

Weathering, erosion, light exposure, water damage, poor methods of excavation and reconstruction, introduced plants and animals, tourism, vandalism and theft have all damaged the site in some way. Two-thirds of the city has been excavated, but the remnants of the city are rapidly deteriorating. The concern for conservation has continually troubled archaeologists. Today, funding is mostly directed into conservation of the site; however, due to the expanse of Pompeii and the scale of the problems, this is inadequate in halting the slow decay of the materials. An estimated US$335 million is needed for all necessary work on Pompeii.[citation needed]

See also

- Pompeii: The Last Day

- Aqua Augusta (Naples)

- Roman aqueducts

- Erotic art in Pompeii and Herculaneum

- The Fires of Pompeii

- House of the Faun

- House of the Vettii

- Villa of the Mysteries

- Mount Pelée (similar destructive eruption at Martinique in 1902)

- Armero tragedy; a city in Colombia that suffered the same fate

- House of Julia Felix

- Robert Rive, 1850s photographer of Pompeii

- Plymouth, Montserrat, a city buried by a volcano in more recent times

- Template:Wikitravel

Notes

- ^ Dossier Musei 2008 - Touring Club Italiano

- ^ Senatore, et al., 2004

- ^ Crowd Control in Ancient Pompeii

- ^ "Patterns of Reconstruction at Pompeii". Iath.virginia.edu. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ^ "Page-3 | Visiting Pompeii | World Features". Archaeology.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ^ Area Vesuvio (in Italian) Retrieved on 18 August 2007

- ^ Account of 1785 eruption by Hester Thrale

- ^ Stromboli Online - Vesuvius & Campi Flegrei

- ^ Visiting Pompeii Retrieved on 18 August 2007

- ^ Wall painting of Vesuvius found in Pompeii

- ^ "The Destruction of Pompeii, 79 AD". Eyewitness to History. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- ^ Gabi Laske. "The A.D. 79 Eruption at Mt. Vesuvius". Lecture notes for UCSD-ERTH15: "Natural Disasters". Retrieved 2008-07-28.

- ^ Stefani, Grete, "La vera data dell'eruzione", Archeo, October 2006, pp. 10-14.)

- ^ Grant, Michael, Cities of Vesuvius, Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, 1976, p.223(footnote no.6 to ch.2)

- ^ La vera data dell'eruzione, by Grete Stefani Archeo, October 2006. no.260, p. 10–14 - resumé at http://www.capitoloprimo.it/archivio/2007_2008/index2.php?option=com_content&do_pdf=1&id=572 (in Italian)

- ^ Grant, Michael, Cities of Vesuvius, Penguin, Harmondsworth, 1976, p.215

- ^ (Ozgenel 2008, p. 13)

- ^ Ozgenel, Lalo, A Tale of Two Cities: In Search of Ancient Pompeii and Herculaneum, METU JFA 2008/1 (25:1), p1-25

- ^ (Ozgenel 2008, p. 19)

- ^ Parslow, Christopher Charles (1995) Rediscovering antiquity: Karl Weber and the excavation of Herculaneum, Pompeii, and Stabiae Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, ISBN 0-521-47150-8

- ^ *Pagano, Mario (1997) I Diari di Scavo di Pompeii, Ercolano e Stabiae di Francesco e Pietro la Vega (1764-1810) "L'Erma" di Bretschneidein, Rome, ISBN 88-7062-967-8 (in Italian)

- ^ POMPEIA d'Ernest Breton (3eme éd. 1870) "Introduction - La résurrection de la ville" in French

- ^ "Orto dei Fuggiaschi (2)". Marketplace.it. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ^ "Orto dei Fuggiaschi (3)". Marketplace.it. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ^ As reported by the Evangelist pressedienst press agency in March, 1998.

- ^ Karl Schefold (2003), Die Dichtung als Führerin zur Klassischen Kunst. Erinnerungen eines Archäologen (Lebenserinnerungen Band 58), edd. M. Rohde-Liegle et al., Hamburg. p. 134 ISBN 3-8300-1017-6.

- ^ Alex Butterworth and Ray Laurence, Pompeii, p. 284

- ^ John William Fletcher, The whole works of ... John Fletcher, p. 328

- ^ Alexander John Scott, Discourses, p. 41

- ^ C. H. SpurgeonVoices From Pompeii

- ^ Nadeau, Barbie Selling Pompeii, Newsweek, April 14, 2008

- ^ Classics at RGSW

- ^ BBC - Doctor Who - News - Rome Sweet Rome

References

- Beard, Mary, 2008, Pompeii: The Life of a Roman Town, Profile Books, ISBN 978-1861975966

- Zarmati, Louise (2005). Heinemann ancient and medieval history: Pompeii and Herculaneum. Heinemann. ISBN 1-74081-195-X.

- Butterworth, Alex and Ray Laurence. Pompeii: The Living City. New York: St. Martin's Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0-312-35585-2

- Ellis, Steven J.R., 'The distribution of bars at Pompeii: archaeological, spatial and viewshed analyses' in: Journal of Roman Archaeology 17, 2004, 371-384.

- Senatore, M.R., J.-D. Stanley, and T.S. Pescatore. 2004. Avalanche-associated mass flows damaged Pompeii several times before the Vesuvius catastrophic eruption in the 79 C.E. Geological Society of America meeting. Nov. 7-10. Denver. Abstract.

- Maiuri, Amedeo, Pompeii, pp, 78-85, in Scientific American, Special Issue: Ancient Cities, c. 1994.

- Cioni, R.; Gurioli, L.; Lanza, R.; Zanella, E. (2004). "Temperatures of the A.D. 79 pyroclastic density current deposits (Vesuvius, Italy)". Journal of Geophysical Research-Solid Earth. 109: B02207. doi:10.1029/2002JB002251.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hodge, A.T. (2001). Roman Aqueducts & Water Supply, 2nd ed. London: Duckworth.

External links

- Pompeii official web site

- Pompeii on Google Street View

- Forum of Pompeii Digital Media Archive (creative commons-licensed photos, laser scans, panoramas), data from a University of Ferrara/CyArk research partnership

- Template:Dmoz

i <3 pie smiles :)