Psychedelic therapy

| Part of a series on |

| Psychedelia |

|---|

|

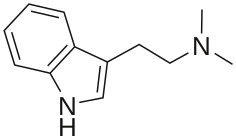

Psychedelic therapy refers to therapeutic practices involving the use of psychedelic drugs, particularly serotonergic psychedelics such as LSD, psilocybin, DMT, MDMA, mescaline, and 2C-B, primarily to assist psychotherapy. As an alternative to synonyms such as "hallucinogen", "entheogen", "psychotomimetic" and other functionally constructed names, the use of the term psychedelic ("mind-manifesting") emphasizes that those who use these drugs as part of a therapeutic practice believe these drugs can facilitate beneficial exploration of the psyche. In contrast to conventional psychiatric medication which is taken by the patient regularly or as-needed, in psychedelic therapy, patients remain in an extended psychotherapy session during the acute activity of the drug and spend the night at the facility. In the sessions with the drug, therapists are nondirective and support the patient in exploring their inner experience. Patients participate in psychotherapy before the drug psychotherapy sessions to prepare them and after the drug psychotherapy to help them integrate their experiences with the drug.[1]

According to one Canadian study conducted in the early years of the 1960s, the greatest interest to the psychiatrist was the fact that LSD allowed for the "illusional perception ('reperception') of the patient's original family figures (e.g. father, mother, parent surrogates and helpers, older siblings, grandparents and the like)", typically experienced as distortions of the psychiatrist's face, body or activity. In technical terms, this was called "perceptualizing the transference".[2]

History

Psychedelic substances which may have therapeutic uses include psilocybin (the main active compound found in magic mushrooms), LSD, and mescaline (the main active compound in the peyote cactus).[3] Although the history behind these substances has hindered research into their potential medicinal value, scientists are now able to conduct studies and renew research that was halted in the 1970s. Some research has shown that these substances have helped people with such mental disorders as obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, alcoholism, depression, and cluster headaches.[4]

Psychedelic therapy, in the broadest possible sense of the term, may have originated from prehistoric knowledge of hallucinogenic plants.[5] Though usually viewed as predominantly spiritual in nature, elements of psychotherapeutic practice can be recognized in the entheogenic or shamanic rituals of many cultures.[6]

Some of the well known particular psychedelic substances that have been used to this day are: LSD, DMT, psilocybin, mescaline, 2C-B, 2C-I, 5-MeO-DMT, AMT, ibogaine and DOM.

Carbogen has also played a role in psychedelic therapy research. Shamans have historically been well known throughout the world to mix two or more of some of the listed substances to produce synergistic effects. See psychoactive, entheogen, hallucinogen, psychotherapy, psychonaut, meditation, trance, mysticism, transcendence (philosophy).

The use of psychedelic agents in Western therapy began in the 1950s, after the widespread distribution of LSD to researchers by its manufacturer, Sandoz Laboratories. Research into experimental, chemotherapeutic and psychotherapeutic uses of psychedelic drugs was conducted in several countries over the next 10–15 years. In addition to the release of dozens of books and creation of six international conferences, more than 1,000 peer-reviewed clinical papers detailing the use of psychedelic compounds (administered to approximately 40,000 patients) were published by the mid-1960s.[7] Proponents believed that psychedelic drugs facilitated psychoanalytic processes, and that they were particularly useful for patients with problems that were otherwise difficult to treat, including alcoholics, although the trials did not meet the methodological standards required today.[8]

One challenge of psychedelic therapy was the greatly variable effects produced by the drugs. According to Stanislav Grof, "The major obstacle to their systematic utilization for therapeutic purposes was the fact that they tended to occur in an elemental fashion, without a recognizable pattern, and frequently to the surprise of both the patient and the therapist. Since the variables determining such reactions were not understood, therapeutic transformations of this kind were not readily replicable."[9] Attempts to produce these experiences in a controlled, non-arbitrary, predictable way resulted in several methods of psychedelic therapy, which are reviewed below.

Researchers like Timothy Leary felt psychedelics could alter the fundamental personality structure or subjective value-system of an individual, to beneficial effect. His experiments with prison inmates were an attempt to reduce recidivism through a few short, intense sessions of psilocybin administered weeks apart with biweekly group therapy sessions in between.[10] Psychedelic therapy was used in a number of other specific patient populations, including alcoholics, children with autism, and persons with terminal illness.[10]

Since ancient times, shamans and medicine men have used psychedelics as a way to gain access to the spirit world. They grow naturally in certain cacti, and in seeds, bark and roots of various plants. Over the course of the '50s and '60s, scientists conducted extensive research to discover whether or not psychedelics have any medicinal purposes. Studies ceased from about 1970, due to the prohibition, to the year 2000. Research currently takes place in universities across the country. Current case studies show LSD can be used to treat addictions to opium and alcohol. Studies also show that psilocybin (magic mushrooms) are useful in treating addictions, depression and severe anxiety. Native American tribes all through North America still practice the use of psychedelics legally with authorization from the federal government. Research is also watched over by the government.

In alcoholism

Studies by Humphrey Osmond, Betty Eisner, and others examined the possibility that psychedelic therapy could treat alcoholism (or, less commonly, other addictions). One review of the usefulness of psychedelic therapy in treating alcoholism concluded that the possibility was neither proven nor disproven.[11] Another thorough meta-analysis from 2012 found that "In a pooled analysis of six randomized controlled clinical trials, a single dose of LSD had a significant beneficial effect on alcohol misuse at the first reported follow-up assessment, which ranged from 1 to 12 months after discharge from each treatment program. This treatment effect from LSD on alcohol misuse was also seen at 2 to 3 months and at 6 months, but was not statistically significant at 12 months post-treatment. Among the three trials that reported total abstinence from alcohol use, there was also a significant beneficial effect of LSD at the first reported follow-up, which ranged from 1 to 3 months after discharge from each treatment program."[12]

Early studies of alcoholics who underwent LSD treatment reported a 50% success rate after a single high-dose session.[13] However, the studies that reported high success rates had insufficient controls, lacked objective measures of genuine change, and failed to conduct rigorous follow-up interviews with subjects. The lack of conclusive evidence notwithstanding, individual case reports are often dramatic. Bill Wilson, the founder of Alcoholics Anonymous conducted medically supervised experiments in the 1950s on the effects of LSD on alcoholism. Bill is quoted as saying "It is a generally acknowledged fact in spiritual development that ego reduction makes the influx of God's grace possible. If, therefore, under LSD we can have a temporary reduction, so that we can better see what we are and where we are going—well, that might be of some help. The goal might become clearer. So I consider LSD to be of some value to some people, and practically no damage to anyone. It will never take the place of any of the existing means by which we can reduce the ego, and keep it reduced."[14] Wilson felt that regular usage of LSD in a carefully controlled, structured setting would be beneficial for many recovering alcoholics. However, he felt this method only should be attempted by individuals with well-developed super-egos.[15] In 1957 Wilson wrote a letter to Heard saying: "I am certain that the LSD experiment has helped me very much. I find myself with a heightened colour perception and an appreciation of beauty almost destroyed by my years of depressions." Most AA members were strongly opposed to his experimenting with a mind-altering substance.[16]

In terminal illness

Richard Yensen, Albert Kurland and other researchers collected evidence that psychedelic therapy could be of use to those suffering from anxiety and other problems associated with terminal illness. In 1965, research consisting of providing a psychedelic experience for the dying was conducted at the Spring Grove State Hospital in Maryland. Of 17 dying patients who received LSD after appropriate therapeutic preparation, one-third improved "dramatically", one-third improved "moderately", and one-third were unchanged by the criteria of reduced tension, depression, pain, and fear of death.[17]

Restrictive regulation

One reason that psychedelic therapy was eventually restricted was concern about the use of drugs by the general public. In the mid-1960s, in response to concerns regarding the proliferation of the unauthorized use of psychedelic drugs by the general public (especially the counterculture), various steps were taken to curtail their use. Bowing to governmental concerns, Sandoz halted production of LSD in 1965, and in many countries LSD was banned, or made available on a very limited basis that made research difficult. Gradually, increasing restrictions were placed on medical and psychiatric research conducted with LSD and other psychedelic substances. In a congressional hearing in 1966, Senator Robert Kennedy questioned the shift of opinion with regards to this potentially rewarding form of treatment, noting that, "Perhaps to some extent we have lost sight of the fact that (LSD) can be very, very helpful in our society if used properly."[18]

By 1970, LSD and many other psychedelics were placed into the most restrictive "Schedule I" category by the United States Drug Enforcement Administration, along with widely used drugs like heroin. Schedule I compounds are claimed to possess "significant potential for abuse and dependence" and have "no recognized medicinal value", effectively rendering them illegal for any purpose without special difficult-to-obtain approvals. The arguments in favor of this regulation are seemingly contradicted by hundreds of scientific and medical articles on the use of psychedelics as aids in psychotherapy. In 1968, Dahlberg and colleagues published an article in the American Journal of Psychiatry that detailed the way in which various forces had successfully discredited legitimate LSD research.[19] The essay argues that individuals in government and the pharmaceutical industry influenced research in the medical community by canceling any ongoing studies and analysis in addition to labeling genuine scientists as charlatans. Despite objections from the scientific community, authorized research into therapeutic applications of psychedelic drugs had been discontinued worldwide by the 1980s.

Continuing trials

Research and therapeutic sessions have nevertheless continued to be performed, in one way or another, to the present day. Some therapists have exploited windows of opportunity preceding scheduling of particular substances (e.g. LSD, Dimethyltryptamine, Psilocybin, 2C-B, Mescaline, MDMA, Cannabis, Ketamine, Ibogaine, Harmaline, Ayahuasca, Salvia divinorum) or developed extensive non-drug techniques for achieving similar states of consciousness (e.g. Holotropic Breathwork). For the most part, however, since the early 1970s, psychedelic therapy has been conducted by an underground network of people willing to conduct therapy sessions using psychedelic substances. Board-certified therapists, in doing this, risked losing both their career and their liberty. In recent years, some researchers, including Charles Grob and Michael Mithoefer, have carried out human studies of psychedelics as possible treatments for various ailments.[citation needed]

2000s resurgence

Research into the pharmacology and neurological and psychiatric effects of psychedelics surged in the mid-2000s.[why?] Most of the renewed clinical research had been conducted with psilocybin, but other studies have investigated the mechanisms and effects of MDMA (ecstasy), ketamine, ayahuasca and LSD.[3][20][21] These studies included, for example, a study of psilocybin to mitigate anxiety in 12 people with terminal cancer, the use of psilocybin in 9 people with OCD, and use of the LSD as an adjunct to psychotherapy for anxiety in 8 people with serious illness.[22][23][24] In general, the drugs remain poorly understood. Their effects are strongly dependent on the environment in which they are given and on the recipient's state of mind.[22]

As of 2014, global treaties listing LSD and psilocybin as "Schedule I" controlled substances still severely restricts research into better understanding these drugs.[23]

Methods

The effects of psychedelic drugs on the human mind are complex, varied and difficult to characterize, and as a result many different "flavors" of psychedelic psychotherapy have been developed by individual practitioners. Some aspects of published accounts of methodologies are discussed below.

Psycholytic therapy

Psycholytic therapy involves the use of low to medium doses of psychedelic drugs, repeatedly at intervals of 1–2 weeks. The therapist is present during the peak of the experience and at other times as required, to assist the patient in processing material that arises and to offer support when necessary. This general form of therapy was utilized mainly to treat patients with neurotic and psychosomatic disorders. The name, coined by Ronald A. Sandison,{{refn|Ronald Sandison first referred to the psycholytic model in 1955 in a speech to the American Psychiatric Association, and used the term ‘psycholytic therapy’ at the 1960 'European Symposium on Psychotherapy Under LSD-25' at Göttingen University convened by Hanscarl Leuner. In 1964 Leuner formed the European Medical Society for Psycholytic Therapy.[25] literally meaning "soul-dissolving", refers to the belief that the therapy can dissolve conflicts in the mind. Psycholytic therapy was historically an important approach to psychedelic psychotherapy in Europe, but it was also practiced in the United States by some psychotherapists including Betty Eisner.

An advantage of psychedelic drugs in exploring the unconscious is that a conscious sliver of the adult ego usually remains alert during the experience.[7]: 196 Throughout the session, patients remain intellectually alert and remember their experiences vividly.[7]: 196 In this highly introspective state, they also are actively cognizant of ego defenses such as projection, denial, and displacement as they react to themselves and their choices in the act of creating them.[7]: 196

The ultimate goal of the therapy is to provide a safe, mutually compassionate context through which the profound and intense reliving of memories can be filtered through the principles of genuine psychotherapy.[citation needed] Aided by the deeply introspective state attained by the patient, the therapist assists him/her in developing a new life framework or personal philosophy that recognizes individual responsibility for change.[7]: 196

In Germany Hanscarl Leuner has designed a psycholytic therapy, which was developed officially, but was used also by some socio-politically motivated underground therapists in the 1970s.[26][27][28]

Psychedelic therapy

Psychedelic therapy involves the use of very high doses of psychedelic drugs, with the aim of promoting transcendental, ecstatic, religious or mystical peak experiences. Patients spend most of the acute period of the drug's activity lying down with eyeshades listening to nonlyrical music and exploring their inner experience. Dialogue with the therapists is sparse during the drug sessions but essential during psychotherapy sessions before and after the drug experience. There are two therapists, one man and one woman. The recent resurgence of research (see above) uses this method.[1] It is more closely aligned to transpersonal psychology than to traditional psychoanalysis. Psychedelic therapy is practiced primarily in North America. The psychedelic therapy method was initiated by Humphry Osmond and Abram Hoffer (with some influence from Al Hubbard) and replicated by Keith Ditman.[29]

Other variations

In Czechoslovakia, Stanislav Grof developed a form of treatment that appeared to bridge both of these main forms. He analyzed the LSD experience in a Freudian or Jungian psychoanalytic context in addition to giving significant value to the overarching transpersonal, mystical, or spiritual experience that often allowed the patient to re-evaluate their entire life philosophy.[7][9]

The Chilean therapist Claudio Naranjo developed a branch of psychedelic therapy that utilized drugs like MDA, MDMA, harmaline, and ibogaine.[7]

Anaclitic therapy

The term anaclitic (from the Ancient Greek "ἀνάκλιτος", anaklitos – "for reclining") refers to primitive, infantile needs and tendencies directed toward a pre-genital love object. Developed by two London psychoanalysts, Joyce Martin and Pauline McCririck, this form of treatment is similar to psycholytic approaches as it is based largely on a psychoanalytic interpretation of abreactions produced by the treatment, but it tends to focus on those experiences in which the patient re-encounters carnal feelings of emotional deprivation and frustration stemming from the infantile needs of their early childhood. As a result, the treatment was developed with the aim to directly fulfill or satisfy those repressed, agonizing cravings for love, physical contact, and other instinctual needs re-lived by the patient. Therefore, the therapist is completely engaged with the subject, as opposed to the traditional detached attitude of the psychoanalyst. With the intense emotional episodes that came with the psychedelic experience, Martin and McCririck aimed to sit in as the "mother" role who would enter into close physical contact with the patients by rocking them, giving them milk from a bottle, etc.[9]

Hypnodelic therapy

Hypnodelic therapy, as the name suggests, was developed with the goal to maximize the power of hypnotic suggestion by combining it with the psychedelic experience. After training the patient to respond to hypnosis, LSD would be administered, and during the onset phase of the drug the patient would be placed into a state of trance. Levine and Ludwig found the combination of these techniques to be more effective than the use of either of these two components separately.[9]

Developments from 1980–present

Owing to the largely illegal nature of psychedelic therapy in this period, little information is available concerning the methods that have been used. Individuals having published information on psychedelic psychotherapy in this period include George Greer, Ann Shulgin (TiHKAL, with Alexander Shulgin), and Myron Stolaroff (The Secret Chief, about the underground therapy done by Leo Zeff) and Athanasios Kafkalides.[30]

See also

- Category:Psychedelic drug researchers

- Concord Prison Experiment

- LSD-25

- History of lysergic acid diethylamide

- MDA

- MDMA

- Psychedelics, dissociatives and deliriants

- Stanislav Grof

- Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies

- Rick Doblin

- Timothy Leary

- James Fadiman

References

- ^ a b "A Manual for MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy in the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder" (PDF). Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. 4 January 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2014.

- ^ Baker EF (December 1964). "The Use of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD) in Psychotherapy". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 91: 1200–2. PMC 1928491. PMID 14226093.

- ^ a b Tupper KW, Wood E, Yensen R, Johnson MW (October 2015). "Psychedelic medicine: a re-emerging therapeutic paradigm". CMAJ. 187 (14): 1054–9. doi:10.1503/cmaj.141124. PMC 4592297. PMID 26350908.

- ^ Garcia-Romeu A, Kersgaard B, Addy PH (August 2016). "Clinical applications of hallucinogens: A review". Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 24 (4): 229–68. doi:10.1037/pha0000084. PMC 5001686. PMID 27454674.

- ^ Guerra-Doce, Elisa (2 January 2015). "Psychoactive Substances in Prehistoric Times: Examining the Archaeological Evidence". Time and Mind. 8 (1): 91–112. doi:10.1080/1751696X.2014.993244.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Winkelman, Michael (2007). "Shamanic Guidelines for Psychedelic Medicine". In Winkelman, Michael; Roberts, Thomas B. (eds.). Psychedelic medicine: new evidence for hallucinogenic substances as treatments. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 978-0-275-99023-7.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g Grinspoon, Lester; Bakalar, James B. "The Psychedelic Drug Therapies". Psychedelic Drugs Reconsidered,. A Drug Policy Classic Reprint from the Lindesmith Center, 1997]. ISBN 978-0-9641568-5-2.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Dyck E (June 2005). "Flashback: psychiatric experimentation with LSD in historical perspective". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie. 50 (7): 381–8. doi:10.1177/070674370505000703. PMID 16086535.

- ^ a b c d Grof, Stanislav (2001). LSD Psychotherapy (3rd ed.). MAPS. ISBN 978-0-9660019-4-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Leary T, Metzner R, Presnell M, Weil G, Schwitzgebel R, Kinne S (1965). "A new behavior change program using psilocybin". Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice. 2 (2): 61–72. doi:10.1037/h0088612.

- ^ Mangini M (1998). "Treatment of alcoholism using psychedelic drugs: a review of the program of research". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 30 (4): 381–418. doi:10.1080/02791072.1998.10399714. PMID 9924844.

- ^ Krebs TS, Johansen PØ (July 2012). "Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) for alcoholism: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 26 (7): 994–1002. doi:10.1177/0269881112439253. PMID 22406913.

- ^ Smart RG, Storm T (March 1964). "The Efficacy of LSD in the Treatment of Alcoholism" (PDF). Quarterly Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 25: 333. Retrieved 25 September 2012.

- ^ "Pass it on" : the story of Bill Wilson and how the A.A. message reached the world. Alcoholics Anonymous World Services. pp. 370–371. ISBN 978-0-916856-12-0.

- ^ Wilson, Bill. The Best of Bill: Reflections on Faith, Fear, Honesty, Humility, and Love. pp. 94–95. ISBN 978-0-933685-41-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ "LSD could help alcoholics stop drinking, AA founder believed". The Guardian. 23 August 2012.

- ^ Yensen R, Dryer D (1999). "Addiction, despair, and the soul: successful psychedelic psychotherapy, a case study". Societat d'Etnopsicologia i Estudis Cognitius. Archived from the original on 2008-06-17.

- ^ "Organization and Coordination of Federal Drug Research and Regulatory Programs: LSD [electronic resource]". Hearings before the United States Senate Committee on Government Operations, Subcommittee on Executive Reorganization, Eighty-Ninth Congress, second session. U.S. Government Publication Office. 22 May 1966. p. 63.

- ^ Dahlberg CC, Mechaneck R, Feldstein S (November 1968). "LSD research: the impact of lay publicity". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 125 (5): 685–9. doi:10.1176/ajp.125.5.685. PMID 5683460.

- ^ Amoroso T (2015). "The Psychopharmacology of ±3,4 Methylenedioxymethamphetamine and its Role in the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 47 (5): 337–44. doi:10.1080/02791072.2015.1094156. PMID 26579955.

- ^ Schenberg EE (2018-07-05). "Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy: A Paradigm Shift in Psychiatric Research and Development". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 9: 733. doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.00733. PMC 6041963. PMID 30026698.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b Halberstadt AL (January 2015). "Recent advances in the neuropsychopharmacology of serotonergic hallucinogens". Behavioural Brain Research. 277: 99–120. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2014.07.016. PMC 4642895. PMID 25036425.

- ^ a b Baumeister D, Barnes G, Giaroli G, Tracy D (August 2014). "Classical hallucinogens as antidepressants? A review of pharmacodynamics and putative clinical roles". Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology. 4 (4): 156–69. doi:10.1177/2045125314527985. PMC 4104707. PMID 25083275.

- ^ Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, Agin-Liebes G, Malone T, Cohen B, Mennenga SE, Belser A, Kalliontzi K, Babb J, Su Z, Corby P, Schmidt BL (December 2016). "Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 30 (12): 1165–1180. doi:10.1177/0269881116675512. PMC 5367551. PMID 27909164.

- ^ Sessa B (2016). "The History of Psychedelics in Medicine". In von Heyden M, Jungaberle H, Majić T (eds.). Handbuch Psychoaktive Substanzen. Springer Reference Psychologie. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-55214-4_96-1. ISBN 978-3-642-55214-4.

- ^ Leuner, Hanscarl (September 1972). "Standpunkte". Kursbuch 29. Das Elend mit der Psyche. II Psychoanalyse (in German). Berlin.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Leuner, Hanscarl. "Alternative Szene" (in German).

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Jungaberle H, Gasser P, Weinhold J, Verres R (2008). Therapie mit psychoaktiven Substanzen : Praxis und Kritik der Psychotherapie mit LSD, Psilocybin und MDMA (in German) (1st ed.). Bern: Hans Huber. ISBN 978-3-456-84606-4.

- ^ Eisner B (1997). "Set, setting, and matrix". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 29 (2): 213–6. doi:10.1080/02791072.1997.10400190. PMID 9250949.

- ^ Stolaroff, Myron (1997). The Secret Chief: Conversations with a pioneer of the underground psychedelic therapy movement. Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies. ISBN 978-0-9660019-1-4.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help)

External links

- The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies

- History of LSD Therapy (Ch. 1 of Grof's, LSD Psychotherapy)

- The Use of Psychedelic Agents with Autistic Schizophrenic Children

- The Second International Conference on the Use of LSD in Psychotherapy and Alcoholism (1967) (entire book)

- Documents for serious Psychonauts, Research papers and articles on the role of psychoactive substances in psychological and shamanic healing practices.

- Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out … Get Well? Article about psychedelic therapy research in LitmusZine.

- Psycholytic and Psychedelic Therapy Research 1931-1995: A Complete international Bibliography Torsten Passie

- WWW Psychedelic Bibliography MAPS, full-text articles

- Nature News - "Ecstasy Could Augment the Benefits of Psychotherapy" (2008).

- Nature News - "Party drug could ease trauma long term" (2010).