Pundravardhana

| History of Bangladesh |

|---|

|

|

|

Pundravardhana (Template:Lang-bn Punḍrôbôrdhôn, Template:Lang-sa), was a territory located in North Bengal (mainly in what is now Bangladesh) in ancient times, home of the Pundra, a group of people not speaking languages of the Indo-European family.[1][2][3]

Etymology

There are several theories regarding the word ‘Pundra’. According to one theory the word ‘Pundra’ owes its origin to a disease called ‘Pandu’. The land where most of the people were suffering from that disease was called Pundrakshetra (land of Pundra). Punda is a species of sugarcane. The land where that species of sugarcane was extensively cultivated was called Pundadesa (land of Punda). According to later Vedic texts like Aitereya Aryanaka of 8th-7th century BC, the Pundra was a group of non-Aryan people who lived east of the Sadanira River (Gandaki River). The Mahabharata also made a similar reference. In the 1st century AD, the land was mentioned as Pundravardhana for the first time in Ashokavadana[4]

Geography

25°30′N 81°30′E / 25.50°N 81.50°E Mahasthangarh, the ancient capital of Pundravardhana is located 11 km (7 mi) north of Bogra on the Bogra-Rangpur highway, with a feeder road (running along the eastern side of the ramparts of the citadel for 1.5 km) leading to Jahajghata and site museum.[5]

Discovery

Several personalities contributed to the discovery and identification of the ruins at Mahasthangarh. F.Buchanan Hamilton was the first European to locate and visit Mahasthangarh in 1808, C.J.O’Donnell, E.V.Westmacott, and Baveridge followed. Alexander Cunningham was the first to identify the place as the capital of Pundravardhana. He visited the site in 1889.[6]

Pundra people

The Pundra were people mentioned in the later Vedic texts. The Digvijay section of Mahabharata places them to the east of Monghyr and associates them with the prince who ruled on the banks of the Kosi.[7] The epigraphs of the Gupta period and ancient Chinese writers place Pundravardhana, land of the Pundras, in North Bengal.[3]

Mythology

There is a story of Rishi Dīrghatamas who begot on the queen of the Asura king Bali five sons named Anga, Vanga, Suhma, Pundra and Kalinga. They founded the five states named after them. The lands of the despised Pundra and Vangas were not only seats of powerful kings but also flourishing centres of Buddhism, Jainism and Hinduism religion. It signifies the first stage of Aryanisation between 5th century BC and 4th century AD.[8]

Empires

Ancient period

Pundranagara or Paundravardhanapura, the ruins of which are located on the banks of the Karatoya in Bogra District of Bangladesh, was located in the territory of Pundravardhana.[3]

While the Pundras and their habitat were looked down upon as impure in later Vedic literature because they fell beyond the pale of Vedic culture,[2] an inscription written in Prakrit in the Brāhmī script of the 3rd century BC, found at Mahasthangarh, ancient site of Pundranagara, indicates that the area imbibed, like adjoining Magadha, many elements of Aryan culture.[9] Buddhism was introduced into North Bengal, if not other parts of Bengal, before Ashoka. Two Votive inscriptions on the railings of the Buddhist stupa at Sanchi of about the 2nd century BC records the gifts of two inhabitants of Punavadhana which undoubtedly stands for Pundravardhana.[10] The impact of Aryan-Brahmana culture was felt in Bengal much after the same spread across northern India. The various non-Aryan people then living in Bengal were powerful and thus the spread of Aryan-Brahman culture was strongly resisted and the assimilation took a long time.[11]

The Mauryans were the first to establish a large empire spread across ancient India, with headquarters at Pataliputra (modern Patna), which was not very far from Pundranagara. According to Ashokavadana, the Mauryan empire Ashoka issued an order to kill all the Ajivikas in Pundravardhana after a non-Buddhist there drew a picture showing the Gautama Buddha bowing at the feet of Nirgrantha Jnatiputra. Around 18,000 followers of the Ajivika sect were executed as a result of this order.[12][13] The end of the Maurya rule around 185 BC was followed by a period of small kingdoms and chaos till the advent of the Guptas in the 4th century AD. Copper plates of the Gupta period mentioned their eastern division as Pundravardhana bhukti (bhukti being a territorial division). The Gupta Empire faced decline in the 6th century AD and the area may have fallen to the Tibetan king Sambatson in 567-79. Subsequently, Bengal was carved into two empires, Samatata in the east and Gauda in the west.[1] There is mention of Pundravardhana being part of Gauda in certain ancient records.[14] It was part of Shashanka’s kingdom in the 7th century AD.[15]

Decline

During his visit to the area in 639-45, the Chinese monk, Xuanzang (Hiuen Tsang), did not mention any king of Pundravardhana in his itinerary records.[1] He traveled from Kajangala to Kamarupa through Pundravardhana.[2]

Xuanzang referred to Pundravardhana as follows:

- There were twenty Buddhist Monasteries and above 3,000 Brethren, by whom the ‘Great and Little Vehicles’ were followed; the Deva-Temples were 100 in number, and the followers of various sects lived pell-mell, the Digambar Nirgranthas being very numerous.[16]

There are references that go to indicate that Pundravardhana lost its eminence in the 7th-8th century. Archaeological excavations at Mahasthangarh indicate the use of the citadel during the Pala period till 12th century AD but no more as a power-centre.[1] It was part of the empire of Chandra kings[17] and Bhoj Verma.[18] The early Muslim rulers from 13th century onwards may have used the territory but by then it was no more important.[1] Its identity gradually faded and it became part of the surrounding area. Even the main city or capital of Pundravardhana, Pundravardhananagar or Paundravardhanapur lost its identity and came to be known as Mahasthan.

Spread of Islam

At Mahasthan is located the mazhar (holy tomb) of Shah Sultan Balkhi Mahisawar, a dervish (holy person devoted to Islam) of royal lineage who came to the Mahasthan area, with the objective of spreading Islam amongst non-Muslim people. He killed the local king in a war and converted the people of the area to Islam and settled there.[5][19]

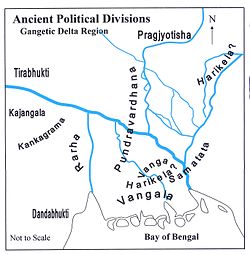

Extent

Pundravardhana, comprised areas of present-day Rajshahi, Bogra, Pabna (in Bangladesh), and Dinajpur (both in India and Bangladesh). According to the Damodarpur copperplate inscription of the time of Budhagupta (c 476-94 AD) the northern limit of Pundravardhana was the Himalayas. The administrative and territorial jurisdiction of Pundravardhana expanded in the Pala period. In the Pala, Chandra and Sena periods Pundravardhana included areas beyond the geographical boundaries of North Bengal.[2] Varendri or Varendri-mandala was a metropolitan district of Pundravardhana. This is supported by several inscriptions.[3] Varendra or Varendri finds a mention primarily from the 10th century onwards, at a time when Pundravardhana was in decline.[20]

Rakhaldas Bandyopadhyay says, “Only North Bengal is not meant by Pundravardhana bhukti, what we now call East Bengal was also part of Pundravardhana or Pundravardhana bhukti. In a copper plate during the rule of Keshab Sendeb, son of Lakshman Sendeb, i.e. in the 12th century, Pundravardhana or Pundravardhana bhukti included areas up to Bikrampur.”[21] In the south Pundravardhana extended to localities in the Sundarbans.[22]

The numerous waterways of the region were the main channels of transportation. However, there are references in ancient literature to some roads. Somadeva's Kathasaritsagara mentions a road from Pundravardhana to Pataliputra. Xuanzang travelled from Kajangala to Pundravardhana, thereafter crossed a wide river and proceeded to Kamarupa. There are indications about a road from Pundravardhana to Mithila, then passing through Pataliputra and Buddha Gaya on to Varanasi and Ayodhya, and finally proceeding to Sindh and Gujarat. It must have been a major trade route.[23]

References

- ^ a b c d e Hossain, Md. Mosharraf, Mahasthan: Anecdote to History, 2006, pp. 69-73, Dibyaprakash, 38/2 ka Bangla Bazar, Dhaka, ISBN 984-483-245-4

- ^ a b c d Ghosh, Suchandra. "Pundravardhana". Banglapedia. Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. Retrieved 10 November 2007.

- ^ a b c d Majumdar, Dr. R.C., History of Ancient Bengal, First published 1971, Reprint 2005, p. 10, Tulshi Prakashani, Kolkata, ISBN 81-89118-01-3.

- ^ Ashokavadana

- ^ a b Hossain, Md. Mosharraf, pp. 14-15.

- ^ Hossain, Md. Mosharraf, pp. 16-19

- ^ It is to be noted that in earlier days the Kosi used to flow through North Bengal. See Karatoya River for details

- ^ Majumdar, Dr. R.C., p. 25

- ^ Majumdar, Dr. R.C., p. 27

- ^ Majumdar, Dr. R.C., p. 454

- ^ Roy, Niharranjan, Bangalir Itihas, Adi Parba, Template:Bn icon, first published 1972, reprint 2005, pp. 216-217, Dey’s Publishing, 13 Bankim Chatterjee Street, Kolkata, ISBN 81-7079-270-3

- ^ John S. Strong (1989). The Legend of King Aśoka: A Study and Translation of the Aśokāvadāna. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 232. ISBN 978-81-208-0616-0. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ^ Beni Madhab Barua (5 May 2010). The Ajivikas. General Books. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-1-152-74433-2. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ^ Bandopadhyay, Rakhaldas, Bangalar Itihas, Template:Bn icon, first published 1928, revised edition 1971, vol I, p 101, Nababharat Publishers, 72 Mahatma Gandhi Road, Kolkata.

- ^ Majumdar, Dr. R.C., p. 63

- ^ Majumdar, Dr. R.C., p. 453

- ^ Bandopadhyay, Rakhaldas, p. 181

- ^ Bandopadhyay, Rakhaldas, p. 230

- ^ Khokon, Leaquat Hossain, 64 Jela Bhraman, 2007, p.129, Anindya Prokash, Dhaka.

- ^ Roy, Niharranjan, p. 116.

- ^ Bandopadhyay, Rakhaldas, p. 49

- ^ Roy, Niharranjan, p.85,

- ^ Roy, Niharranjan, pp. 91-93