Vasculitis

| Vasculitis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Vasculitides[1] |

| |

| Petechia and purpura on the lower limb due to medication-induced vasculitis | |

| Pronunciation | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology, Immunology |

| Symptoms | Weight loss, fever, myalgia, purpura |

| Complications | Gangrene, Myocardial infarction |

Vasculitis is a group of disorders that destroy blood vessels by inflammation.[2] Both arteries and veins are affected. Lymphangitis (inflammation of lymphatic vessels) is sometimes considered a type of vasculitis.[3] Vasculitis is primarily caused by leukocyte migration and resultant damage. Although both occur in vasculitis, inflammation of veins (phlebitis) or arteries (arteritis) on their own are separate entities.

Signs and symptoms[edit]

Possible signs and symptoms include:[4][5]

- General symptoms: fever, unintentional weight loss, tiredness

- Skin: palpable purpura, livedo reticularis

- Muscles and joints: muscle pain or inflammation, joint pain or joint swelling

- Nervous system: mononeuritis multiplex, headache, stroke, tinnitus, reduced visual acuity, acute visual loss

- Heart and arteries: heart attack, high blood pressure, gangrene, heart palpitations

- Respiratory tract: nosebleeds, bloody cough, lung infiltrates

- GI tract: abdominal pain, bloody stool, perforations (hole in the GI tract)

- Kidneys: inflammation of the kidney's filtration units (glomeruli)

- Ear and Nose: sinus infections, ear infections, and hearing loss

Causes[edit]

There are several different etiologies for vasculitides. Although infections usually involve vessels as a component of more extensive tissue damage, they can also directly or indirectly cause vasculitic syndromes through immune-mediated secondary events. Simple vascular thrombosis usually only affects the luminal process, but through the process of thrombus organization, it can also occasionally cause a more chronic vasculitic syndrome. The autoimmune etiologies, a particular family of diseases characterized by dysregulated immune responses that produce particular pathophysiologic signs and symptoms, are more prevalent.[6]

Classification[edit]

Primary systemic, secondary, and single-organ vasculitis are distinguished using the highest classification level in the 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature.[7]

Primary systemic vasculitis[edit]

Primary systemic vasculitis is catogized by the size of the vessels mainly involved. Primary systemic vasculitis includes large-vessel vasculitis, medium-vessel vasculitis, small-vessel vasculitis, and variable-vessel vasculitis.[7]

Large vessel vasculitis[edit]

The 2012 Chapel Hill Consensus Conference defines large vessel vasculitis (LVV) as a type of vasculitis that can affect any size artery, but it usually affects the aorta and its major branches more frequently than other vasculitides.[7] Takayasu arteritis (TA) and giant cell arteritis (GCA) are the two main forms of LVV.[8]

Medium vessel vasculitis[edit]

Medium vessel vasculitis (MVV) is a type of vasculitis that mostly affects the medium arteries, which are the major arteries that supply the viscera and their branches. Any size artery could be impacted, though.[7] The two primary types are polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) and Kawasaki disease (KD).[8]

Small vessel vasculitis[edit]

Small vessel vasculitis (SVV) is separated into immune complex SVV and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV).[7]

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis (AAV) is a necrotizing vasculitis linked to MPO-ANCA or PR3-ANCA that primarily affects small vessels and has few or no immune deposits. AAV is further classified as eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss) (EGPA), granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Wegener's) (GPA), and microscopic polyangiitis (MPA).[7]

Immune complex small vessel vasculitis (SVV) is vasculitis that primarily affects small vessels and has moderate to significant immunoglobulin and complement component deposits on the vessel wall.[7] Normocomplementemic urticarial vasculitis (HUV) (anti-C1q vasculitis), cryoglobulinemic vasculitis (CV), IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Schönlein) (IgAV), and anti-glomerular basement membrane (anti-GBM) disease are the categories of immune complex SVV.[8]

Variable vessel vasculitis[edit]

Variable vessel vasculitis (VVV) is a kind of vasculitis that may impact vessels of all sizes (small, medium, and large) and any type (arteries, veins, and capillaries), with no particular type of vessel being predominantly affected.[7] This category includes Behcet's disease (BD) and Cogan's syndrome (CS).[8]

Secondary vasculitis[edit]

The subset of illnesses known as secondary vasculitis are those believed to be brought on by an underlying ailment or exposure. Systemic illnesses (such as rheumatoid arthritis), cancer, drug exposure, and infection are the primary causes of vasculitis; however, there are still few factors that have a conclusively shown pathogenic relationship to the condition.[9] Vasculitis frequently coexists with infections, and several infections, including hepatitis B and C, HIV, infective endocarditis, and tuberculosis, are significant secondary causes of vasculitis.[10] Except for rheumatoid vasculitis, the majority of secondary vasculitis forms are exceedingly rare.[11]

Single-organ vasculitis[edit]

Single-organ vasculitis, formerly known as "localized," "limited," "isolated," or "nonsystemic" vasculitis, refers to vasculitis that is limited to one organ or organ system. Examples of this type of vasculitis include gastrointestinal, cutaneous, and peripheral nerve vasculitis.[9]

Diagnosis[edit]

- Laboratory tests of blood or body fluids are performed for patients with active vasculitis. Their results will generally show signs of inflammation in the body, such as increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), anemia, increased white blood cell count and eosinophilia. Other possible findings are elevated antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) levels and hematuria.

- Other organ functional tests may be abnormal. Specific abnormalities depend on the degree of various organs involvement. A brain SPECT can show decreased blood flow to the brain and brain damage.

- The definite diagnosis of vasculitis is established after a biopsy of involved organ or tissue, such as skin, sinuses, lung, nerve, brain, and kidney. The biopsy elucidates the pattern of blood vessel inflammation.

- Some types of vasculitis display leukocytoclasis, which is vascular damage caused by nuclear debris from infiltrating neutrophils.[12] It typically presents as palpable purpura.[12] Conditions with leucocytoclasis mainly include hypersensitivity vasculitis (also called leukocytoclastic vasculitis) and cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis (also called cutaneous leukocytoclastic angiitis).

- An alternative to biopsy can be an angiogram (x-ray test of the blood vessels). It can demonstrate characteristic patterns of inflammation in affected blood vessels.

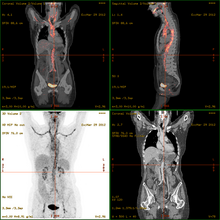

- 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG-PET/CT)has become a widely used imaging tool in patients with suspected Large Vessel Vasculitis, due to the enhanced glucose metabolism of inflamed vessel walls.[13] The combined evaluation of the intensity and the extension of FDG vessel uptake at diagnosis can predict the clinical course of the disease, separating patients with favourable or complicated progress.[14]

- Acute onset of vasculitis-like symptoms in small children or babies may instead be the life-threatening purpura fulminans, usually associated with severe infection.

| Disease | Serologic test | Antigen | Associated laboratory features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | ANA including antibodies to dsDNA and ENA [including SM, Ro (SSA), La (SSB), and RNP] | Nuclear antigens | Leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, Coombs' test, complement activation: low serum concentrations of C3 and C4, positive immunofluorescence using Crithidia luciliae as substrate, antiphospholipid antibodies (i.e. anticardiolipin, lupus anticoagulant, false-positive VDRL) |

| Goodpasture's disease | Anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody | Epitope on noncollagen domain of type IV collagen | |

| Small vessel vasculitis | |||

| Microscopic polyangiitis | Perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody | Myeloperoxidase | Elevated CRP |

| Granulomatosis with polyangiitis | Cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody | Proteinase 3 (PR3) | Elevated CRP |

| Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis | perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody in some cases | Myeloperoxidase | Elevated CRP and eosinophilia |

| IgA vasculitis (Henoch-Schönlein purpura) | None | ||

| Cryoglobulinemia | Cryoglobulins, rheumatoid factor, complement components, hepatitis C | ||

| Medium vessel vasculitis | |||

| Classical polyarteritis nodosa | None | Elevated CRP and eosinophilia | |

| Kawasaki's Disease | None | Elevated CRP and ESR |

In this table: ANA = antinuclear antibodies, CRP = C-reactive protein, ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate, dsDNA = double-stranded DNA, ENA = extractable nuclear antigens, RNP = ribonucleoproteins; VDRL = Venereal Disease Research Laboratory

Treatment[16][17][edit]

Treatment depends on the type of vasculitis. If an offending antigen is recognized, e.g., hepatitis infection, it should be treated appropriately along with the treatment regimen of vasculitis. Treatment regimens center upon the specific diagnosis and the severity or extent of the disease. The approach to treatment for any vasculitis generally includes three components: remission induction, remission maintenance, and monitoring.

Glucocorticoids are the first-line treatment for patients with vasculitis used with or without immunosuppressive agents. The type of vasculitis guides the choice of immunosuppressive agents. Methotrexate (MTX), azathioprine (AZA), mycophenolate (MMF), cyclophosphamide (CYC), rituximab (RTX), intravenous immunoglobulin, plasma exchange, etc., have all been used in various treatment regimens in different forms of vasculitis.[12] Once the condition is in remission, slow, downward glucocorticoid titration should commence to maintain control of disease activity and minimize the risks of drug toxicity. Patients and physicians should know the short-term and long-term toxic side effects of therapeutic agents for monitoring.

In this article, we will discuss the treatment and management of GCA, GPA, and MPA briefly.

Initial treatment for GCA includes steroids, starting at doses of 40 to 60 mg a day, as single or divided doses. Glucocorticoid treatment should be initiated without delay in patients with a strong suspicion for GCA. Intravenous pulse steroids are an option in patients with recent vision loss. After remission, steroids should be slowly tapered off. Methotrexate and azathioprine can serve as steroid-sparing agents. Tocilizumab has been approved recently for treatment of GCA.[16][17]

Patients with AAV have poor survival rates without treatment, with 81% mortality after one year of diagnosis. Current treatment regimens aim to induce remission and then maintain remission. Depending on disease severity, with organ- and life-threatening manifestations warranting the most aggressive therapy, treatments are tailored for various types of AAV. EULAR/ERA-EDTA published guidelines for the management of AAV in 2016, and patients with the non-organ threatening disease can start on a regimen of methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil in combination with glucocorticoid. Patients with life-threatening disease should start on a regimen of cyclophosphamide or rituximab with glucocorticoids. Plasma exchange can be a consideration in patients with progressive renal failure or pulmonary hemorrhage. For maintenance therapy, regimens of azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, or rituximab with a tapering course of steroids have demonstrated efficacy.[16][17]

Prognosis[edit]

Long-term survival of patients with vasculitis highly depends on the diagnosis, response to therapy, and adverse effects of drugs, including the occurrence of infections. In a study assessing long-term survival in ANCA-associated vasculitis: the 1-, 2- and 5-year survival was 88%, 85%, and 78%, respectively. The mortality ratio was 2.6 compared with the general population.[15] Mortality reports derive from both active vasculitic disease and complications of therapy.[17]

References[edit]

- ^ "Vasculitis — Definition". Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- ^ "Glossary of dermatopathological terms. DermNet NZ". Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- ^ "Vasculitis" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- ^ "The Johns Hopkins Vasculitis Center — Symptoms of Vasculitis". Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 7 May 2009.

- ^ "Vasculitis — Symptoms | NHLBI, NIH". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. 22 May 2023. Retrieved 23 October 2023.

- ^ Seidman, M.A. (2014). "Vasculitis". Pathobiology of Human Disease. Elsevier. pp. 2995–3005. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-386456-7.05506-4. ISBN 978-0-12-386457-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jennette, J. C.; Falk, R. J.; Bacon, P. A.; Basu, N.; Cid, M. C.; Ferrario, F.; Flores-Suarez, L. F.; Gross, W. L.; Guillevin, L.; Hagen, E. C.; Hoffman, G. S.; Jayne, D. R.; Kallenberg, C. G. M.; Lamprecht, P.; Langford, C. A.; Luqmani, R. A.; Mahr, A. D.; Matteson, E. L.; Merkel, P. A.; Ozen, S.; Pusey, C. D.; Rasmussen, N.; Rees, A. J.; Scott, D. G. I.; Specks, U.; Stone, J. H.; Takahashi, K.; Watts, R. A. (27 December 2012). "2012 Revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides". Arthritis & Rheumatism. 65 (1). Wiley: 1–11. doi:10.1002/art.37715. ISSN 0004-3591. PMID 23045170.

- ^ a b c d Jennette, J. Charles (27 September 2013). "Overview of the 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference nomenclature of vasculitides". Clinical and Experimental Nephrology. 17 (5). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 603–606. doi:10.1007/s10157-013-0869-6. ISSN 1342-1751. PMC 4029362. PMID 24072416.

- ^ a b Mahr, Alfred; de Menthon, Mathilde (2015). "Classification and classification criteria for vasculitis". Current Opinion in Rheumatology. 27 (1). Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health): 1–9. doi:10.1097/bor.0000000000000134. ISSN 1040-8711. PMID 25415531. S2CID 24318541.

- ^ Suresh, E (1 August 2006). "Diagnostic approach to patients with suspected vasculitis". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 82 (970). Oxford University Press (OUP): 483–488. doi:10.1136/pgmj.2005.042648. ISSN 0032-5473. PMC 2585712. PMID 16891436.

- ^ Luqmani, Raashid Ahmed; Pathare, Sanjay; Kwok-fai, Tony Lee (2005). "How to diagnose and treat secondary forms of vasculitis". Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 19 (2). Elsevier BV: 321–336. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2004.11.002. ISSN 1521-6942. PMID 15857799.

- ^ a b A Brooke W Eastham, Ruth Ann Vleugels and Jeffrey P Callen (12 July 2021). "Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis". Medscape. Updated: Oct 25, 2018

- ^ Maffioli L, Mazzone A (2014). "Giant-Cell Arteritis and Polymyalgia Rheumatica". NEJM. 371 (17): 1652–1653. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1409206. PMC 4277693. PMID 25337761.

- ^ Dellavedova L, Carletto M, Faggioli P, Sciascera A, Del Sole A, Mazzone A, Maffioli LS (2015). "The prognostic value of baseline 18F-FDG PET/CT in steroid-naïve large-vessel vasculitis: introduction of volume-based parameters". European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging. 55 (2): 340–8. doi:10.1007/s00259-015-3148-9. PMID 26250689. S2CID 21446786.

- ^ Burtis CA, Ashwood ER, Bruns DE (2012). Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistry and Molecular Diagnostics, 5th edition. Elsevier Saunders. p. 1568. ISBN 978-1-4160-6164-9.

- ^ a b c Rheumatism, BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and European League Against (1 June 2022). "Correction: EULAR/ERA-EDTA recommendations for the management of ANCA-associated vasculitis". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 81 (6): e109–e109. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209133corr2. ISSN 0003-4967. PMID 35577366.

- ^ a b c d Jatwani, Shraddha; Goyal, Amandeep (2024), "Vasculitis", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 31424770, retrieved 26 April 2024