Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky: Difference between revisions

reverting; the WP:DEADHORSE is on the talk page; sticks provided. There is no gay composer prior to modern times whose sexuality is better documented than this one |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 240: | Line 240: | ||

[[Category:Russian music critics]] |

[[Category:Russian music critics]] |

||

[[Category:Cause of death disputed]] |

[[Category:Cause of death disputed]] |

||

[[Category:Gay musicians]] |

|||

[[Category:LGBT composers]] |

[[Category:LGBT composers]] |

||

[[Category:LGBT people from Russia]] |

[[Category:LGBT people from Russia]] |

||

Revision as of 05:55, 21 December 2008

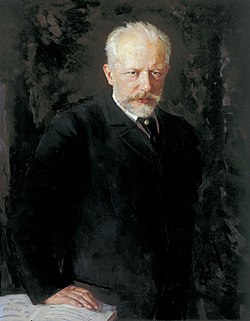

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky[1] (Russian: Пётр Ильич Чайковский, [2] ) (May 7 [O.S. April 25] 1840 – November 6 [O.S. October 25] 1893) was a Russian composer of the Romantic era. While not part of the nationalistic music group known as "The Five", Tchaikovsky wrote music which, in the opinion of Harold C. Schonberg, was distinctly Russian: plangent, introspective, with modally-inflected melody and harmony.[3]

While the Five's contributions were important in their own right in developing an independent Russian voice and consciousness in classical music, Tchaikovsky became a dominant figure in 19th century Russian music and known both in and outside Russia as its greatest musical talent. His formal conservatory training instilled in him Western-oriented attitudes and techniques, allowing him to show a wide range and breadth of technique. This breadth ranged from a poised "Classical" form simulating 18th century Rococo elegance to a style more characteristic of Russian nationalists or forming a musical idiom as a channel to express his own overwrought emotions.[4]

Even with this diversity of approach, Tchaikovsky's essential outlook musically remained Russian, both in his use of native folk song and his deep absorption in Russian life and ways of thought. This Russianness of mindset ensured that he would not become a mere imitator of Western technique. His natural gift for melody, based mainly on themes of tremendous eloquence and emotive power and supported by matching resources in harmony and orchestration, has always made his music appealing to the public. However, his hard-won professional technique and an ability to harness it to express his emotional life gave Tchaikovsky the ability to realize his potential more fully than any other Russian composer of his time.[5]

Although always popular with audiences, Tchaikovsky had at times been judged harshly by musicians and composers. However, his reputation as a significant composer is now generally regarded as secure. [6]

Life

Childhood

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky was born in Votkinsk, a small town in present-day Udmurtia (at the time the Vyatka Guberniya of Imperial Russia). His father, Ilya Petrovich, was the son of a government mining engineer, of Ukrainian descent. His mother, Alexandra, was a Russian woman of partial French ancestry and the second of Ilya's three wives. Pyotr was the older brother (by some ten years) of the dramatist, librettist, and translator Modest Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

In 1843, Tchaikovsky acquired a French governess, Fanny Dürbach. Her love and affection for her charge is said to have provided a counter to Alexandra, who is described by one biographer as a cold, unhappy, distant parent not given to displays of physical affection.[7] However other writers claim that Alexandra doted on her son.[8]

Tchaikovsky began piano lessons at age four with a local woman. Musically precocious, he could read music as well as his teacher within three years. However, his parents' passion for his musical talent soon cooled. Feeling inferior due to their humble origins, the family sent Tchaikovsky in 1850 to a school for the "lesser nobility" or gentry called the School of Jurisprudence in St. Petersburg to secure him a career as a civil servant. The minimum age for acceptance was 12. For Tchaikovsky, this meant two years boarding at the School of Jurisprudence's preparatory school, 800 miles (1,300 km) from his family.

Early manhood

A second blow came on June 25, 1854 with Alexandra's death from cholera. Tchaikovsky felt unable to inform his former governness Fanny Dürbach of this until two years later.[9] Within a month of her death, he was making his first serious efforts at composition, a waltz in her memory. Several writers have claimed that the loss of his mother was formative on Tchaikovsky's sexual development, and couple this with his experience of the same-sex practices said to be widespread among students at the School of Jurisprudence.[10] Whatever the truth of this, some friendships with fellow students, such as Aleksey Apukhtin and Vladimir Gerard, were intense enough to last the rest of his life.[11]

While music was not considered a high priority at the Institute, Tchaikovsky was taken to the theater and the opera with classmates regularly. He was fond of works by Rossini, Bellini, Verdi and Mozart. A piano manufacturer, Franz Becker, made occasional visits as a token music teacher and gave lessons. This was the only music instruction Tchaikovsky received at school. In 1855, Ilya Tchaikovsky funded private studies outside the Institute for his son with Rudolph Kündinger, a well-known piano teacher from Nuremberg. Ilya also questioned Kündinger about a musical career for his son. He replied that nothing suggested a potential composer or even a fine performer. Tchaikovsky was told to finish his course work, then try for a post in the Ministry of Justice.[12]

Tchaikovsky graduated on May 25, 1859 with the rank of titular counselor, the lowest rung of the civil service ladder. On June 15, he was appointed to the Ministry of Justice. Six months later he became a junior assistant to his department; two months after that, a senior assistant. There Tchaikovsky remained for the rest of his three-year civil service career.[13]

In 1861, he attended classes in music theory taught by Nikolai Zaremba through the Russian Musical Society (RMS). The following year he followed Zaremba to the new St Petersburg Conservatory. Tchaikovsky followed but did not give up his Ministry post "until I am quite certain that I am destined to be a musician rather than a civil servant."[14]. From 1862 to 1865, he studied harmony, counterpoint and fugue with Zaremba. Anton Rubinstein, director and founder of the Conservatory, taught him instrumentation and composition.[15] Rubinstein was impressed by Tchaikovsky's musical talent. However, this did not stop either him or Zaremba from clashing with Tchaikovsky over his First Symphony when he submitted it to them for their perusal. By this time, the young composer had already graduated from the conservatory. The symphony was given its first complete performance in February 1868, where it was well received.[16]

Dealings with The Five

As Tchaikovsky studied with Zaremba at the Western-oriented St. Petersburg Conservatory, critic Vladimir Stasov and composer Mily Balakirev espoused a nationalistic, less Western-oriented and more locally idiomatic school of Russian music. Stasov and Balakirev recruited what would be known as The Mighty Handful or kuchka (better known in English as "The Five") in St. Petersburg. Balakirev considered academicism to be not a help but a threat to musical imagination. Along with Stasov, he attacked Anton Rubinstein and the Conservatory relentlessly in print as well as verbally at every opportunity.[17]

Since Tchaikovsky became Rubinstein's best known student, he was initially considered by association as a natural target for attack, especially as fodder for César Cui's criticism.[18] This attitude changed slightly when Rubinstein exited the St. Petersburg musical scene in 1867. Tchaikovsky entered into a working relationship with Balakirev. The result was Tchaikovsky's first masterpiece, the fantasy-overture Romeo and Juliet, a work The Five wholeheartedly embraced.[19] When Tchaikovsky wrote a positive review of Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov's Fantasy on Serbian Themes, he was welcomed into the circle despite concerns about his academic background.[20] His Second Symphony, nicknamed the Little Russian, in its initial form was also received enthusiastically by the group.

He remained friendly but never intimate with most of The Five, ambivalent about their music; their goals and aesthetics did not match his.[21] He took pains to ensure his musical independence from them as well as from the conservative faction at the Conservatory — a course of action facilitated by his accepting the professorship at the Moscow Conservatory offered to him by Nikolai Rubinstein.[22] When Rimsky-Korsakov was offered a professorship at the St. Petersburg Conservatory after Zaremba had left, it was Tchaikovsky to whom he turned for advice and guidance.[23] Later, Tchaikovsky enjoyed closer relations with Alexander Glazunov, Anatoly Lyadov and, at least on the surface, the older Rimsky-Korsakov.[24]

Mature composer

Anton Rubinstein's younger brother Nikolai asked Tchaikovsky after graduation to become professor of harmony, composition, and the history of music at the Moscow Conservatory. Tchaikovsky gladly accepted the position as his father had retired and lost his property. At the same time he wrote music criticism and continued as a professional composer. Some of his best-known works from this period include the First Piano Concerto, the Variations on a Rococo Theme for violoncello and orchestra, the Little Russian Symphony and the ballet Swan Lake. The First Piano Concerto suffered an initial rejection by its intended dedicatee, Nikolai Rubinstein, as notably recounted three years after the fact by the composer. The work went instead to pianist Hans von Bulow, whose playing had impressed Tchaikovsky when he appeared in Moscow in March 1874. Bulow premiered the work in Boston in October 1875. Rubinstein eventually championed the work himself.[25]

Turmoil in life and music

The importance of Tchaikovsky's sexuality and its consequences on the personal expression in his compositions is significant. The possibility that Tchaikovsky was gay has been inferred from the composer's own writings as well as those of his brother Modest although some historians consider this evidence scant or non-existent.[26]

Of undoubted significance was Tchaikovsky's ill-starred marriage to one of his former composition students, Antonina Miliukova. Tchaikovsky had decided to "marry whoever will have me" just before Antonina appeared on the scene. His favorite pupil Vladimir Shilovsky had married suddenly in late April 1877.[27][28] Shilovsky's wedding may, in turn, have spurred Tchaikovsky to consider such a step himself.[29] The brief time with his wife drove him to an emotional crisis.[30]

Paradoxically, the marriage's strain on Tchaikovsky may have actually enhanced his creativity. The Fourth Symphony and the opera Eugene Onegin could be considered proof of this. He finished both these works in the six months from his engagement to his "rest cure" in Clarens, Switzerland following his marriage. They are arguably two of his finest compositions.[31] While in Clarens he also composed his Violin Concerto, with the technical assistance of one of his former students, violinist Yosif Kotek. Like the First Piano Concerto, the work would be rejected initially by its intended dedicatee, in this case the noted virtuoso and pedagogue Leopold Auer, and was premiered by another soloist (Adolph Brodsky), then belatedly accepted and played to great public succcess by Auer. In addition to playing the concerto himself, Auer would also teach the work to his students, including Jascha Heifitz and Nathan Milstein. As for Kotek, he would help establish contact between Tchaikovsky and the widow of a railway magnate, Nadezhda von Meck, who would become the composer's patron and confidante (more below).[32]

While the concerto would eventually enjoy public success, the audience hissed at its premiere in Vienna[33] and it was denigrated by music critic Eduard Hanslick:

The Russian composer Tchaikovsky is surely no ordinary talent, but rather, an inflated one, obsessed with posturing as a man of genius, and lacking all discrimination and taste.... the same can be said for his new, long, and ambitious Violin Concerto. For a while it proceeds soberly, musically, and not mindlessly, but soon vulgarity gains the upper hand and dominates until the end of the first movement. The violin is no longer played: it is tugged about, torn, beaten black and blue.... The Adagio is well on the way to reconciling us and winning us over when, all too soon, it breaks off to make way for a finale that transports us to the brutal and wretched jollity of a Russian church festival. We see a host of gross and savage faces, hear crude curses, and smell the booze. In the course of a discussion of obscener illustrations, Friedrich Vischer once maintained that there were pictures whose stink one could see. Tchaikovsky's Violin Concerto confronts us for the first time with the hideous idea that there may be musical compositions whose stink one can hear.[34]

Auer later mentioned that Hanslick's comment that "the last movement was redolent of vodka ... did credit neither to his good judgment nor to his reputation as a critic."[35]

The intensity of personal emotion now flowing through Tchaikovsky's works was entirely new to Russian music.[36] It prompted some Russian commentators to place his name alongside that of novelist Fyodor Dostoyevsky.[36] Like Dostoyevsky's characters, they felt the musical hero in Tchaikovsky's music persisted in exploring the meaning of life while trapped in a fatal love-death-faith triangle.[36] The critic Osoovski wrote of the two, "With a hidden passion they both stop at moments of horror, total spiritual collapse, and finding acute sweetness in the cold trepidation of the heart before the abyss, they both force the reader to experience those feelings, too."[37]

Mme. von Meck

Nadezhda von Meck, the wealthy widow of a Russian railway tycoon and an influential patron of the arts, wanted to commission some chamber pieces, and in supporting Tchaikovsky became an important element in his life. She eventually paid Tchaikovsky an annual subsidy of 6,000 rubles. This would also allow him to resign from the Moscow Conservatory in October 1878 and concentrate primarily on composition.[38] With von Meck's patronage came a relationship that, at her insistence, was mainly epistolary. They exchanged well over over 1,000 letters, some of them quite lengthy, between 1877 and 1890. In these letters Tchaikovsky was more open to von Meck about much of his life and his creative processes than to any other person.[39]

Von Meck remained a fully dedicated supporter of Tchaikovsky and all his works. She also became a vital enabler in his day-to-day existence.[40] As he explained to her,

There is something so special about our relationship that it often stops me in my tracks with amazement. I have told you more than once, I believe, that you have come to seem to me the hand of Fate itself, watching over me and protecting me. The very fact that I do not know you personally, while feeling so close to you, accords you in my eyes the special status of an unseen but benevolent presence, like a benign Providence.[41]

Tchaikovsky and von Meck also became related by a marriage. One of her sons, Nikolay, married Tchaikovsky's niece Anna Davydova in 1884.[42]

However, after 13 years von Meck (suffering from health problems that made writing difficult, family pressure, and the mismanagement of her estate by her son) suddenly ended the relationship. The break was announced in a letter delivered by a trusted servant (rather than by post as previously) that contained a request that he not forget her, and was accompanied by a year's subsidy in advance. She claimed bankruptcy, which while not literally true was apparently a real threat at the time. Tchaikovsky, now a success throughout Europe, no longer needed her money. Her friendship and encouragement were another matter. Losing that companionship devastated him.[43]

Later career

Tchaikovsky returned to Moscow Conservatory in the Autumn of 1879, having been away from Russia for a year after his marriage disintegrated. Shortly into that term, however, he resigned. He settled in Kamenka, yet travelled incessantly. Assured of a regular income from von Meck, he wandered around Europe and rural Russia. Not staying long in any one place, he lived mainly alone, avoiding social contact whenever possible. This may have been due partly to troubles with Antonina. She alternately accepted and refused divorce and at one point exacerbated matters by moving into the apartment directly above her husband's.[44][45] Perhaps for this reason, except for his piano trio, which he wrote upon the death of Nikolai Rubinstein, his best work from this period is found in genres which did not depend heavily on personal expression.[44]

While Tchaikovsky's reputation grew rapidly outside Russia, "it was considered obligatory [in progressive musical circles in Russia] to treat Tchaikovsky as a renegade, a master overly dependent on the West," Alexandre Benois wrote in his memoirs.[46] In 1880, this assessment changed practically overnight. During commemoration ceremonies for the Pushkin Monument in Moscow, Dostoyevsky charged that the poet had given a prophetic call to Russia for "universal unity" with the West.[46] An unprecedented acclaim for Dostoyevsky's message spread throughout Russia. Disdain for Tchaikovsky's music dissipated. He even drew a cult following among the young intelligentsia of St. Petersburg, including Benois, Leon Bakst and Sergei Diaghilev.[citation needed]

During 1884, Tchaikovsky began to shed his unsociability and restlessness. In 1885 Tsar Alexander III conferred upon Tchaikovsky the Order of St. Vladimir (fourth class). With it came hereditary nobility. The tsar's decoration was a visible seal of official approval that helped the composer's social rehabilitation.[47] That year he resettled in Russia. The tsar asked personally for a new production of Eugene Onegin to be staged in St. Petersburg. The opera had previously been seen only in Moscow, produced by a student ensemble from the conservatory. He had Onegin staged not at the Mariyinsky Theater but in the Bolshoi kamennïy theater. This act served notice that Tchaikovsky's music was replacing Italian opera as the official imperial art. Thanks to Vsevolozhsky, Tchaikovsky received a lifetime pension of 3000 rubles per year from the tsar. This essentially made him the premier court composer, at least in practice if not in actual title.[48]

1885 also saw his debut as a guest conductor. Within a year, he was in considerable demand throughout Europe and Russia in appearances which helped him overcome a life-long stage fright and boosted his self-assurance.[citation needed] He wrote to von Meck, "Would you now recognize in this Russian musician traveling across Europe that man who, only a few years ago, had absconded from life in society and lived in seclusion abroad or in the country!!!"[49] In 1888 he conducted the premiere of his Fifth Symphony in St. Petersburg, repeating the work a week later with the premiere of his tone poem Hamlet. While both works were received with extreme enthusiasm by audiences, critics proved hostile, with Cui calling the symphony "routine" and "meretricious."[50] Nevertheless, Tchaikovsky continued to conduct the symphony in Russia and Europe.[51] Conducting brought him to America in 1891. He led the New York Music Society's orchestra in his Marche Slave[52] at the inaugural concert of New York's Carnegie Hall.

In 1893, the University of Cambridge awarded Tchaikovsky an honorary Doctor of Music degree.[citation needed]

Death

Tchaikovsky died in St. Petersburg on November 6, 1893, nine days after the premiere of his Sixth Symphony, the Pathétique. Due to its formal innovation plus the overwhelming emotional content of its outer movements, the work was received by the public with silent incomprehension.[53] The second performance, under conductor Eduard Nápravník, took place 20 days later at a memorial concert[54] and was much more favorably received.[55] The Pathétique has since become one of Tchaikovsky's best known works.

Tchaikovsky's death has traditionally been attributed to cholera, most probably contracted through drinking contaminated water several days earlier.[56] However, some have theorized that his death was a suicide.[57]

Music

Reception and reputaton

One of Tchaikovsky's prime assets as a composer was what Harold Schonberg terms "a sweet, inexhaustible, supersensuous fund of melody ... touched with neuroticism, as emotional as a scream from a window on a dark night."[58] This melody helped make the composer famous in Russia and internationally, while the surcharged emotionalism which could accompany it polarized listeners. "From the beginning," Schonberg continues, "most listeners enjoyed the emotional bath in which they were immersed by the composer. Others, more inhibited, rejected Tchaikovsky's message out of hand or despised themselves for responding to it.... For a long time Tchaikovsky, so loved by the public, was discounted by many connoisseurs and musicians as nothing more than a weeping machine."[59] Eduard Hanslick wrote about the Violin Concerto that he had heard music which stank to the ear.[60] William Forster Abtrop, normally disinclined toward much contemporary music, wrote more positively about Tchaikovsky's Fifth Symphony in his notes for a Boston Symphony Orchestra performance of the work:

Tchaikovsky is one of the leading composers, some think the leading composer, of the present Russian School. He is fond of emphasizing the pecular character of Russian melody in his works, plans his compositions in general on a large scale, and delights in strong effects. He has been criticized for the occasional excessive harshness of his harmony, for now and then descending to the trivial and the tawdry in his ornamental figuration, and also for a tendency to develop comparatively insignificant material to inordinate length. But, in spite of the prevailing wild savagery of his music, its originally and the genuineness of its fire and sentiment are not to be denied.[61]

This sentiment did not stop Abtrop from writing about the same work in the Boston Evening Transcript:

[The Fifth Symphony] is less untamed in spirit than the composer's B-flat minor [Piano Concerto], less recklessly harsh in its polyphonic writing, less indicative of the composer's disposition to swear a theme's way through a stone wall.... In the Finale we have all the untamed fury of the Cossack, whetting itself for deeds of atrocity, against all the sterility of the Russian steppes. The furious peoration sounds like nothing so much as a hoarde of of demons struggling in a torrent of brandy, the music growing drunker and drunker. Pandemonium, delerium tremens, raving, and above all, noise were confounded![62]

More recently, Tchaikovsky's music has received a professsional reevaluation, with musicians reacting more favorably to its tunefulness and craftsmanship. His orchestration remains a source for admiration, while the last three numbered symphonies are now considered a successful compromise between the classical-era requirements of the form and the demand for new forms dictated by post-Romantic musical and extramusical concerns. Those three symphonies, along with two of his concertos, his three ballets, the Romeo and Juliet fantasy-overture, the 1812 Overture, the Marche Slave and two of his operas, retain their popularity. Almost as popular are the Serenade for Strings, Francesca da Rimini and the Capriccio italien.[63]

Creative range

Program music such as Francesca da Rimini or the Manfred Symphony was as much a part of the composer's artistic credo as the expression of his "lyric ego."[64] There is also a group of compositions which fall outside the dichotomy of program music versus "lyrical ego," where he hearkens toward pre-Romantic aesthetics. Works in this group include the orchestral suites, Capriccio Italien and the Serenade for Strings.[65] He displays his clearest link to pre-Romantic sensitivities in retrospective works such as the Variations on a Rococo Theme and Mozartiana, a collection of orchestrations based on Mozart piano pieces and a Liszt transcription of a Mozart work. The Violin Concerto also looks back to pre-Romantic aesthetics.[66]

Public considerations

Tchaikovsky believed that his professionalism in combining skill and high standards in his musical works separated him from his contemporaries in The Five. He shared several of their ideals, including an emphasis on national character in music. His aim, however, was linking those ideals to a standard high enough to satisfy Western European criteria. His professionalism also fueled his desire to reach a broad public, not just nationally but internationally, which he would eventually do.[67]

He may also have been influenced by the almost "eighteenth-century" patronage prevalent in Russia at the time, still strongly influenced by its aristocracy.[68] Tchaikovsky found no aesthetic conflict in playing to the tastes of his audiences. The patriotic themes and stylization of 18th-century melodies in his works lined up with the values of the Russian aristocracy.[69]

Compositional style

Melody

Tchaikovsky's melodies range from Western style to folksong stylizations and occasionally folksongs themselves. He also sometimes employs the practice of repetition which is characteristic of certain Russian folk songs, extending themselves by constant variations on a single motif. More usually, however, his repetitions reflect the sequential practices of Western practices, and could be extended at immense length. At times these repetitions could build into an emotional experience of almost unbearable intensity. He also allows modal practices to influence his original melodies repeatedly, though not very strongly. Dance tunes, especially waltzes, are his most characteristic melodiesance tunes, filling not only his ballets but also compositions in other genres except church music. Also prevalent are impassioned cantilenas often possessing strong contours, with a full-blooded emotion that is often supported by a harmony of complementary expressive tensions.[70]

Rhythm

Tchaikovsky experimented occasionally with unusual meters. More usually, as typified by his dance tunes, he empoloys a very Russian sense of dynamic rhythm to provide a firm, essentially regular meter. This meter sometimed becomes the main expressive agent in some movements due to its being used so vigorously. He also employs a strong metrical drive as synthetic propulsion in large-scale symphonic movements in place of organic growth and movement.[71]

Harmony

Tchaikovsky also practiced a wide range of harmony, from the Western harmonic and textural practices of his first two string quartets to the unorthodox progressions in the center of the finale of the Second Symphony. This finale also contains one of the few times Tchaikovsky employed the whole tone scale in the bass; this was a practice more typically used by the Five. Usually Tchaikovsky uses relatively conventional harmonic progressions, such as the circle of fifths in the first love theme of Romeo and Juliet. Frequently, however, these progressions involve a liberality in the use of pedals which is typical in the work of Russian composers as well as a decorative use of chromaticism.[72]

Orchestration

Tchaikovsky wrote most of his music for the orchestra. His musical textures therefore became increasingly conditioned by the orchestral colors he employed, especially after the Second Orchestral Suite. While he was grounded in Western orchestral practices, Tchaikovsky preferred bright and sharply differentiated orchestral coloring in the tradition established by Glinka and followed typically by Russian composers since then. He tends to exploit primarily the treble instruments for their fleet delicacy, though he balances this tendency with a matching exploration of the darker, even gloomy sounds of the bass instruments.[73]

Tchaikovsky in fiction

Authors, dramatists and film-makers have found Tchaikovsky's life a compelling source of raw material. For discussion of plays, films, operas, and other works incorporating Tchaikovsky as a character, see Tchaikovsky in fiction.

Media

Other media files for the Romeo and Juliet overture, the Violin concerto, and the 1812 Overture can be found in their respective articles. Template:Multi-listen start Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen end

See also

- Nadezhda von Meck

- Antonina Miliukova Tchaikovskaya

- Nikolai Grigoryevich Rubinstein

- International Tchaikovsky Competition

- Tchaikovsky Symphony Orchestra of Moscow Radio

- List of ballets by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

- Category:Compositions by Pyotr Tchaikovsky

- Category:Ballets by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Notes

- ^ Note: His names are also transliterated Piotr, Petr, or Peter; Ilitsch, Ilich, Il'ich or Illyich; and Tschaikowski, Tschaikowsky, Chajkovskij and Chaikovsky (and other versions; Russian transliteration can vary between languages)

- ^ Russian pronunciation: [ˈpʲɵtr ɪlʲˈjit͡ɕ ˌt͡ɕɪjˈkofskʲɪj]

- ^ Schonberg, Harold C., Lives of the Great Composers (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 3rd ed 1997), 366.

- ^ Brown, New Grove, 18:606.

- ^ Brown, New Grove, 18:606-7, 628.

- ^ Brown, New Grove, 18:628-9.

- ^ Holden, Anthony, Tchaikovsky: A Biography (New York: Random House, 1995), 6.

- ^ Poznansky, 5.

- ^ Brown, Tchaikovsky: The Early Years, 1840-1874 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1978, 47; Tchaikovsky: The Man and His Music (New York: Pegasus Books, 2007), 12.; Holden, 23.; Tchaikovsky, P., Polnoye sobraniye sochinery: literaturnïye proizvedeniya i perepiska [Complete edition: literary works and correspondence] In progress (Moscow, 1953-present), 5:56-57.; Warrack, 29.

- ^ Holden, 22, 26.; >Poznansky, 32-37.; Warrack, 30

- ^ Holden, 23.

- ^ Holden, 24-5; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 31.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 14.

- ^ As quoted in Holden, 38-9.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 20; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 36-8.

- ^ Brown, New Grove, 18:608.

- ^ Maes, 39.

- ^ Holden, 52.

- ^ Brown, Tchaikovsky: Man and Music, 49.

- ^ Maes, 44.

- ^ Maes, 49.

- ^ Holden, 64.

- ^ Maes, 48.

- ^ Rimsky-Korsakov, 308.

- ^ Steinberg, Concerto, 474-6.

- ^ Dr. Petr Beckmann claims Tchaikovsky's homosexuality has been asserted "not without bias ... too often ... done by tone setters who had a stake in the outcome." (Petr Beckmann, Musical Musings, Golem Press, August 1989.) He cites musicologist E. Yoffe's assurance that "there is nothing in Tchaikovsky's voluminous correspondence (5,000 letters) or in his eleven diaries (1873, 1884, 1886-1891) that refers directly to his alleged homosexuality." Tchaikovsky biographer André Lischké however claims that Modest clearly states in his unpublished autobiography that both he and his brother were gay; he also asserts that most papers dealing with the composer's homosexuality were censored in official publications. Certain biographers, including Rictor Norton and Alexander Poznansky, conclude not only that Tchaikovsky was gay but that some of the composer's closest relationships were of the same sex. Poznansky surmises that the composer "eventually came to see his sexual peculiarities as an insurmountable and even natural part of his personality ... without experiencing any serious psychological damage." British musicologist and scholar Henry Zajaczkowski however claims his research "along psychoanalytical lines" points instead to "a severe unconscious inhibition by the composer of his sexual feelings", adding, "If the composer's response to possible sexual objects was either to use and discard them or to idolize them, it shows that he was unable to form an integrated, secure relationship with another man. That, surely, was [Tchaikovsky's] tragedy". (Zajaczkowski, Henry, The Musical Times, cxxxiii, no. 1797, November 1992, 574. As quoted in Holden, 394.) In summary, Tchaikovsky's sexuality remains a significant bone of contention amongst his biographers and academic interpreters.

- ^ Poznansky, 204.Pioznansky also asserts that Shilovsky was gay, and that they had shared a mutual bond of affection for just over a decade.(Poznansky, 95, 126).

- ^ Tchaikovsky, M.I., Zhizn' Petra Il'icha Chaikovskoyo [Life of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky], 3 vols. (Moscow and Leipzig, 1900-1902), 1:258-259.

- ^ Poznansky, 204.

- ^ Holden,126, 145, 148, 150.

- ^ Brown, Tchaikovsky: The Man and His Music, 143.

- ^ Steinberg, Concerto, 484-5.

- ^ Steinberg, 487.

- ^ Hanslick, Eduard, Music Criticisms 1850-1900, ed. and trans. Henry Pleasants (Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1963). As quoted in Steinberg, Concerto, 487.

- ^ As quoted in Steinberg, 486.

- ^ a b c Volkov, 115.

- ^ Osoovskii, A.V., Muzykal'no-kritcvheskie stat'i, 1894-1912 (Musical Criticism articles, 189401912) (Leningrad, 1971), 171. As quoted in Volkov, 116.

- ^ Compared to average wages of the time, 6,000 rubles a year was a small fortune. A minor government official had to support his family on 300-400 rubles a year.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 134; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 108, 130-3.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 134.

- ^ Letter to von Meck, January 21, 1878. As quoted in Holden, 159.

- ^ Holden, 231-2.

- ^ Brown, Tchaikovsky: The Final Years, 1885-1893 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1991), 287-289; Tchaikovsky: The Man and His Music, 385-386.: Chaikovskii, P.I., Perepiska s N.F. fon Meck (1876-1890) [Correspondence with N.F. von Meck], ed. Zhdanov, Vladimir and Zhegin, Nikolai, 3 vols. (Moscow and Lenningrad, 1980), 3:611. : Holden, 289 : Poznansky, 521, 526.

- ^ a b Brown, New Grove, 18:619.

- ^ He listed Antonina's accusations to him in detail to Modest: "I am a deceiver who married her in order to hide my true nature ... I insulted her every day, her sufferings at my hands were great ... she is appalled by my shameful vice, etc., etc." He may have lived the rest of his life in dread of Antonina's power to expose publicly his sexual leanings (Holden, 155).

- ^ a b Volkov, 126.

- ^ Brown, New Grove, 18:621.

- ^ Maes, 140.

- ^ As quoted in Brown, Tchaikovsky: The Man and His Music, 329.

- ^ Holden, 272.

- ^ Holden, 273.

- ^ So identified by the New York press. According to Carnegie Hall archivist Gino Francesconi, Tchaikovsky may have actually conducted his Festival Coronation March.

- ^ Holden, 351.

- ^ Steinberg, 635.

- ^ Holden, 371.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 431-2; Holden, 371; Warrack, Tchaikovsky, 269-270.

- ^ Brown, Man and Music, 431-5; Holden, 373-400.

- ^ Schonberg, 366.

- ^ Schonberg, 367.

- ^ Hanslick, Eduard, Musical Criticisms 1850-1900, ed. and trans. Henry Pleasants (Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1963).

- ^ Boston Symphony Orchestra program book, October 21-22, 1892. As Quoted in Steinberg, Symphony, 630.

- ^ Boston Evening Transcript, October 23, 1892. As quoted in Steinberg, Symphony, 631

- ^ Schonberg, 367.

- ^ Maes, 154.

- ^ Maes, 154-155.

- ^ Maes, 156.

- ^ Maes (2002), 73.

- ^ In this patronage patron and artist often met on equal terms. Dedications of works to patrons were not gestures of humble gratitude but expressions of artistic partnership. The dedication of the Fourth Symphony to von Meck is known to be a seal on their friendship. Tchaikovsky's relationship with Duke Konstantin Konstantinovich bore creative fruit in the Six Songs, Op. 63, for which the grand duke wrote the words.Maes, 139-141.

- ^ Maes, 137.

- ^ Brown, New Grove, 18:628.

- ^ Brown, New Grove, 18:628.

- ^ Brown, New Grove, 18:628.

- ^ Brown, New Grove, 18:628.

Bibliography

- ed Abraham, Gerald, Music of Tchaikovsky (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1946). ISBN n/a.

- Abraham, Gerald, "Operas and Incidental Music"

- Alshvang, A., tr. I. Freiman, "The Songs"

- Cooper, Martin, "The Symphonies"

- Dickinson, A.E.F., "The Piano Music"

- Evans, Edwin, "The Ballets"

- Mason, Colin, "The Chamber Music"

- Wood, Ralph W., "Miscellaneous Orchestral Works"

- Brown, David, ed. Stanley Sadie, The New Grove Encyclopedia of Music and Musicians (London: MacMillian, 1980), 20 vols. ISBN 0-333-23111-2.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Early Years, 1840-1874 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1978). ISBN 0-393-07535-2.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Crisis Years, 1874-1878, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1983). ISBN 0-393-01707-9.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Years of Wandering, 1878-1885, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1986). ISBN 0-393-02311-7.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Final Years, 1885-1893, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1991). ISBN 0-393-03099-7.

- Brown, David, Tchaikovsky: The Man and His Music (New York: Pegasus Books, 2007). ISBN 0-571-23194-2.

- Figes, Orlando, Natasha's Dance: A Cultural History of Russia (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2002). ISBN 0-8050-5783-8 (hc.).

- Hanson, Lawrence and Hanson, Elisabeth, Tchaikovsky: The Man Behind the Music (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company). Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 66-13606.

- Holden, Anthony, Tchaikovsky: A Biography (New York: Random House, 1995). ISBN 0-679-42006-1.

- Maes, Francis, tr. Arnold J. Pomerans and Erica Pomerans, A History of Russian Music: From Kamarinskaya to Babi Yar (Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2002). ISBN 0-520-21815-9.

- Mochulsky, Konstantin, tr. Minihan, Michael A., Dostoyevsky: His Life and Work (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1967). Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 65-10833.

- Poznansky, Alexander Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man (New York: Schirmer Books, 1991). ISBN 0-02-871885-2.

- Rimsky-Korsakov, Nikolai, Letoppis Moyey Muzykalnoy Zhizni (St. Petersburg, 1909), published in English as My Musical Life (New York: Knopf, 1925, 3rd ed. 1942). ISBN n/a.

- Schonberg, Harold C. Lives of the Great Composers (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 3rd ed. 1997).

- Steinberg, Michael, The Symphony (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995).

- Tchaikovsky, Modest, Zhizn P.I. Chaykovskovo [Tchaikovsky's life], 3 vols. (Moscow, 1900-1902).

- Tchaikovsky, Pyotr, Perepiska s N.F. von Meck [Correspondence with Nadzehda von Meck], 3 vols. (Moscow and Lenningrad, 1934-1936).

- Tchaikovsky, Pyotr, Polnoye sobraniye sochinery: literaturnïye proizvedeniya i perepiska [Complete Edition: literary works and correspondence], 17 vols. (Moscow, 1953-1981).

- Volkov, Solomon, tr. Bouis, Antonina W., St. Petersburg: A Cultural History (New York: The Free Press, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc., 1995). ISBN 0-02-874052-1.

- Warrack, John, Tchaikovsky Symphonies and Concertos (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1969). Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 78-105437.

- Warrack, John, Tchaikovsky (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1973). SBN 684-13558-2.

- Wiley, Roland John, Tchaikovsky's Ballets (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1985). ISBN 0-198-16249-9.

Further reading

- Greenberg, Robert "Great Masters: Tchaikovsky – His Life and Music"

- Kamien, Roger. Music : An Appreciation. Mcgraw-Hill College; 3rd edition (August 1, 1997). ISBN 0-07-036521-0.

- ed. John Knowles Paine, Theodore Thomas, and Karl Klauser (1891). Famous Composers and Their Works, J.B. Millet Company.

- Meck Galina Von, Tchaikovsky Ilyich Piotr, Young Percy M. Tchaikovsky Cooper Square Publishers; 1st Cooper Square Press ed edition (October, 2000) ISBN 0-8154-1087-5.

- Meck, Nadezhda Von Tchaikovsky Peter Ilyich, To My Best Friend: Correspondence Between Tchaikovsky and Nadezhda Von Meck 1876-1878 (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993) ISBN 0-19-816158-1.

- Poznansky, Alexander & Langston, Brett The Tchaikovsky Handbook: A guide to the man and his music. (Indiana University Press, 2002).

- Vol. 1. Thematic Catalogue of Works, Catalogue of Photographs, Autobiography. ISBN 0-253-33921-9.

- Vol. 2. Catalogue of Letters, Genealogy, Bibliography. ISBN 0-253-33947-2.

- Poznansky, Alexander, Tchaikovsky's Last Days, (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), ISBN 0-19-816596-X.

- Poznansky, Alexander. Tchaikovsky through others' eyes. (Bloomington: Indiana Univ. Press, 1999). ISBN 0-253-33545-0.

External links

- Tchaikovsky Research (active site)

- Istituto Musicale Tchaikovsky (Italy) (active site)

- Tchaikovsky (inactive site)

- Tchaikovsky page (inactive site)

- PBS Great Performances biography of Tchaikovsky

- Tchaikovsky cylinder recordings, from the Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project at the University of California, Santa Barbara Library.

- Tchaikovsky's sacred works by Polyansky

- Biography of Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts

- (Italian) Tchaikovsky: listen a playlist on Magazzini-Sonori

Public Domain Sheet Music:

- www.kreusch-sheet-music.net Free Scores by Tchaikovsky

- Mutopia Project Tchaikovsky Sheet Music at Mutopia

- Template:WIMA

- Free scores by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Romantic composers

- Russian composers

- Opera composers

- Ballet composers

- Russian ballet

- Russian Orthodox Christians

- Russian music critics

- Cause of death disputed

- LGBT composers

- LGBT people from Russia

- Imperial School of Jurisprudence alumni

- Russians of French descent

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

- Christian composers

- 1840 births

- 1893 deaths