Rumble Fish

| Rumble Fish | |

|---|---|

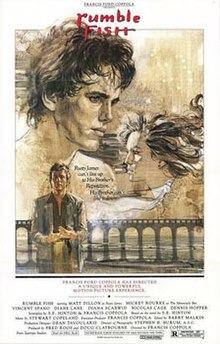

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Francis Ford Coppola |

| Screenplay by | S. E. Hinton Francis Ford Coppola |

| Produced by | Francis Ford Coppola Doug Claybourne Fred Roos |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Stephen H. Burum |

| Edited by | Barry Malkin |

| Music by | Stewart Copeland |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 94 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $10 million |

| Box office | $2,494,480[1] |

Rumble Fish is an American 1983 drama film directed by Francis Ford Coppola. It is based on the novel Rumble Fish by S. E. Hinton, who also co-wrote the screenplay.

The film centers on the relationship between Motorcycle Boy (Mickey Rourke), a revered former gang leader wishing to live a more peaceful life, and his younger brother, Rusty James (Matt Dillon), an uncool teenaged hoodlum who aspires to become as feared as Motorcycle Boy. The film's marketing tagline was, "Rusty James can't live up to his brother's reputation. His brother can't live it down."

Coppola wrote the screenplay for the film with Hinton on his days off from shooting The Outsiders. He made the films back-to-back, retaining much of the same cast and crew. The film is notable for its avant-garde style with a film noir feel, shot on stark high-contrast black-and-white film, using the spherical cinematographic process with allusions to French New Wave cinema and German Expressionism. Rumble Fish features an experimental score by Stewart Copeland, drummer of the musical group The Police, who used a Musync, a new device at the time.[2]

Plot

Set in Tulsa, Oklahoma, the film begins in a diner called Bennys Billiards, where local tough guy Rusty James is told by Midget that rival group leader Biff Wilcox wants to meet him that night in an abandoned garage lot for a fight. Accepting the challenge, Rusty James then talks with his friends — the wily Smokey, loyal B.J., and nerdy Steve - who all have a different take on the forthcoming fight. Steve mentions that Rusty James' older brother, "The Motorcycle Boy," would not be pleased with the fight as he had previously created a truce forbidding gang fights, or "rumbles." Rusty James dismisses him, saying that Motorcycle Boy (whose real name is never revealed) has been gone for two months, leaving without explanation or promise of return.

Rusty James visits his girlfriend, Patty, then rendezvous with his cadre and walks to the abandoned garage lot, where Biff and his buddies suddenly appear. The two battle, with the fight ending when Rusty James disarms Biff and beats him almost unconscious. Motorcycle Boy arrives dramatically on his motorcycle and this distracts Rusty James who is gashed by Biff in the side with a shard of glass. Incensed, Motorcycle Boy sends his motorcycle flying into Biff. The Motorcycle Boy and Steve take Rusty James home (past Officer Patterson, a street cop who's long had it in for the Motorcycle Boy) and nurse him to health through the night. Steve and the injured Rusty James talk about how Motorcycle Boy is 21 years old, colorblind, partially deaf, and noticeably aloof — the last trait causing many to believe he is insane.

The Motorcycle Boy and Rusty James share the next evening with their alcoholic, welfare-dependent father, who says that the Motorcycle Boy takes after his mother whereas, it is implied, Rusty James takes after him. Things start to go wrong for Rusty James: he's kicked out of school after his frequent fights. Despite Rusty James' desire to do so, The Motorcycle Boy implies that he has no interest in reviving any gang activity. Rusty James fools around with another girl and is dumped by Patty.

The two brothers and Steve head across the river one night to a strip of bars, where Rusty James enjoys being away from his troubles. The Motorcycle Boy mentions that he located their long-lost mother during his recent trip while she was with a movie producer, which took him to California although he did not reach the ocean. Later, Steve and Rusty James wander drunkenly home, and are attacked by thugs, but both are saved by the Motorcycle Boy. As he nurses Rusty James again, the Motorcycle Boy tells him that the gang life and the rumbles he yearns for and idolizes are not what he believes them to be. Steve calls the Motorcycle Boy crazy, a claim which the Motorcycle Boy does not deny — further prompting Rusty James to believe his brother is insane, just like his runaway mother supposedly was.

Rusty James meets up with the Motorcycle Boy the next day in a pet store, where the latter is strangely fascinated with the Siamese fighting fish, which he refers to as "rumble fish". Officer Patterson suspects they will try to rob the store. The brothers leave and meet their father, who explains to Rusty James that, contrary to popular belief, neither his mother nor brother are crazy, but rather they were both born with an acute perception. The brothers go for a motorcycle ride through the city and arrive at the Pet Store where the Motorcycle Boy breaks in and starts to set the animals loose. Rusty James makes a last-gasp effort to convince his brother to reunite with him, but the Motorcycle Boy refuses, explaining that the differences between them are too great for them to ever have the life Rusty James speaks of. The Motorcycle Boy takes the fish and rushes to free them in the river, but is shot by Officer Patterson before he can. Rusty James, after hearing the gunshot, finishes his brother's last attempt while a large crowd of people converges on his body.

Rusty James finally reaches the Pacific Ocean (something the Motorcycle Boy never got to do) and enjoys the shining sun and flocks of birds flying around the beach.

Cast

- Matt Dillon as Rusty James

- Mickey Rourke as the Motorcycle Boy

- Diane Lane as Patty

- Dennis Hopper as Father

- Diana Scarwid as Cassandra

- Vincent Spano as Steve

- Nicolas Cage as Smokey

- Chris Penn as B.J. Jackson

- Larry Fishburne as Midget

- William Smith as Officer Patterson

- Glenn Withrow as Biff Wilcox

- Tom Waits as Benny

- Sofia Coppola as Donna

- S. E. Hinton as Hooker on Strip

Development

Francis Ford Coppola was drawn to S. E. Hinton's novel Rumble Fish because of the strong personal identification he had with the subject matter — a younger brother who hero-worships an older, intellectually superior brother, which mirrored the relationship between Coppola and his brother, August.[3] A dedication to August appears as the film's final end credit. The director said that he "started to use Rumble Fish as my carrot for what I promised myself when I finished The Outsiders".[4] Halfway through the production of The Outsiders, Coppola decided that he wanted to retain the same production team, stay in Tulsa, and shoot Rumble Fish right after The Outsiders. He wrote the screenplay for Rumble Fish with Hinton on Sundays, their day off from shooting The Outsiders.[3] During rehearsals, Matt got used to the adult-like acting behavior and situations after having been in The Outsiders. Dillon and Rourke developed a friendship when filming, getting used to their interesting, mischievous characters.

Pre-production

Warner Bros. was not happy with an early cut of The Outsiders and passed on distributing Rumble Fish.[5] Despite the lack of financing in place, Coppola completely recorded the film on video during two weeks of rehearsals in a former school gymnasium and afterwards was able to show the cast and crew a rough draft of the film.[6] To get Rourke into the mindset of his character, Coppola gave him books written by Albert Camus and a biography of Napoleon.[7] The Motorcycle Boy's look was patterned after Camus complete with trademark cigarette dangling out of the corner of his mouth — taken from a photograph of the author that Rourke used as a visual handle.[8] Rourke remembers that he approached his character as "an actor who no longer finds his work interesting".[5]

Coppola hired Michael Smuin, a choreographer and co-director of the San Francisco Ballet, to stage the fight scene between Rusty James and Biff Wilcox because he liked the way he choreographed violence.[6] He asked Smuin to include specific visual elements: a motorcycle, broken glass, knives, gushing water and blood. The choreographer spent a week designing the sequence. Smuin also staged the street dance between Rourke and Diana Scarwid, modeling it after one in Picnic featuring William Holden and Kim Novak.[6]

Before filming started, Coppola ran regular screenings of old films during the evenings to familiarize the cast and in particular, the crew with his visual concept for Rumble Fish.[6] Most notably, Coppola showed Anatole Litvak's Decision Before Dawn, the inspiration for the film's smoky look, F. W. Murnau's The Last Laugh to show Matt Dillon how silent actor Emil Jennings used body language to convey emotions, and Robert Wiene's The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, which became Rumble Fish's "stylistic prototype".[6] Coppola's extensive use of shadows, oblique angles, exaggerated compositions, and an abundance of smoke and fog are all hallmarks of these German Expressionist films. Godfrey Reggio's Koyaanisqatsi, shot mainly in time-lapse photography, motivated Coppola to use this technique to animate the sky in his own film.[6]

Principal photography

Six weeks into production, Coppola made a deal with Universal Studios and principal photography began on July 12, 1982 with the director declaring, "Rumble Fish will be to The Outsiders what Apocalypse Now was to The Godfather."[8] He shot in deserted areas at the edge of Tulsa with many scenes captured via a hand-held camera in order to make the audience feel uneasy. He also had shadows painted on the walls of the sets to make them look ominous.[9] In the dream sequence where Rusty James floats outside of his body Matt Dillon wore a body mold which was moved by an articulated arm and also flown on wires.[10]

To mix the black-and-white footage of Rusty James and the Motorcycle Boy in the pet store looking at the Siamese fighting fish in color, Burum shot the actors in black and white and then projected that footage on a rear projection screen. They put the fish tank in front of it with the tropical fish and shot it all with color film.[11] Filming finished by mid-September 1982, on schedule and on budget.[9]

The film is notable for its avant-garde style, shot on stark high-contrast black-and-white film, using the spherical cinematographic process with allusions to French New Wave cinema. The striking black-and-white photography of the film's cinematographer, Stephen H. Burum, lies in two main sources: the films of Orson Welles and German cinema of the 1920s.[12] When the film was in its pre-production phase, Coppola asked Burum how he wanted to film it and they agreed that it might be the only chance they were ever going to have to make a black-and-white film.[10]

Soundtrack

| Untitled | |

|---|---|

Coppola envisioned a largely experimental score to complement his images.[13] He began to devise a mainly percussive soundtrack to symbolize the idea of time running out. As Coppola worked on it, he realized that he needed help from a professional musician. He asked Stewart Copeland, then drummer of the musical group The Police, to improvise a rhythm track. Coppola soon concluded that Copeland was a far superior composer and let him take over.[13] Copeland recorded street sounds of Tulsa and mixed them into the soundtrack with the use of Musync—a music and tempo editing hardware and software system invented by Robert Randles (subsequently nominated for an Oscar for Scientific Achievement), to modify the tempo of his compositions and synchronize them with the action in the film. [14] [13]

An edited version of the song "Don't Box Me In", a collaboration between Copeland and singer/songwriter Stan Ridgway, was released as a single and enjoyed significant radio airplay.

All songs written by Stewart Copeland, except where noted.

- "Don't Box Me In" (Copeland, Stan Ridgway) – 4:40

- "Tulsa Tango" – 3:42

- "Our Mother Is Alive" – 4:16

- "Party at Someone Else's Place" – 2:25

- "Biff Gets Stomped by Rusty James" – 2:27

- "Brothers on Wheels" – 4:20

- "West Tulsa Story" – 3:59

- "Tulsa Rags" – 1:39

- "Father on the Stairs" – 3:01

- "Hostile Bridge to Benny's" – 1:53

- "Your Mother Is Not Crazy" – 2:48

- "Personal Midget/Cain's Ballroom" – 5:55

- "Motorboy's Fate" – 2:03

Differences from the novel

Coppola did not employ the flashback structure of the novel.[15] He also removed a few passages from the novel that further established Steve and Rusty James' relationship in order to focus more on the brothers' relationship.

- In the film, the Motorcycle Boy is more attentive and paternal toward Rusty James than he is in the novel.

- In the novel, Rusty James uses a bike chain to disarm Biff, whereas in the film he uses a sweater.

- In the novel Biff slashes Rusty James with a knife rather than a pane of glass and Motorcycle Boy breaks Biff's wrist instead of ramming him with his motorcycle.[16]

- The Motorcycle Boy's self-destructive behavior at the film's conclusion is less motivated in the film than in the novel.

- In the novel, Rusty James gets arrested after Motorcycle Boy is shot and never makes the promise to ride the motorcycle.

- The film ends with Rusty James arriving at the ocean on a motorcycle while the novel ends with Rusty James meeting Steve in California five years after Motorcycle Boy's death.

Themes

The theme of time passing faster than the characters realize is conveyed through time-lapse photography of clouds racing across the sky and numerous shots of clocks. The black-and-white photography was meant to convey the Motorcycle Boy's color blindness while also evoking film noir through frequent use of oblique angles, exaggerated compositions, dark alleys, and foggy streets.[17]

Reception

At Rumble Fish's world premiere at the New York Film Festival, there were several walkouts and at the end of the screening, boos and catcalls.[18] Former head of production at Paramount Pictures Michael Daly remembers legendary producer Robert Evans' reaction to Coppola's film, "Evans went to see Rumble Fish, and he remembers being shaken by how far Coppola had strayed from Hollywood. Evans says, 'I was scared. I couldn't understand any of it.'"[4]

At the San Sebastián International Film Festival, it won the International Critics' Big Award. The movie was a box office disaster on initial release, grossing only $2.5 million domestically;[1] its estimated budget was $10 million; a large sum for the time. Coppola utilized many new filmmaking techniques never before used in the production of a motion picture. The film polarized critics, some mainstream reviewers enjoying it, while others disliked Coppola's film, criticizing Coppola's style over substance approach. The film has since grown in esteem and is held in high regard by many film fans.

Rumble Fish was released on October 8, 1983 and grossed $18,985 on its opening weekend, playing in only one theater. Its widest release was in 296 theaters and it finally grossed $2.5 million domestically.[19]

Critical response

Rumble Fish was not well received by most mainstream critics upon its initial release, receiving nine negative reviews in New York City, mostly from broadcast media and newspapers with harsh reviews by David Denby in New York and Andrew Sarris in The Village Voice.[20] In her review for The New York Times, Janet Maslin wrote that "the film is so furiously overloaded, so crammed with extravagant touches, that any hint of a central thread is obscured".[21] Film critic Roger Ebert gave the film three-and-a-half out of four stars and wrote, "I thought Rumble Fish was offbeat, daring, and utterly original. Who but Coppola could make this film? And, of course, who but Coppola would want to?"[22] Gary Arnold in The Washington Post wrote, "It's virtually impossible to be drawn into the characters' identities and conflicts at even an introductory, rudimentary level, and the rackety distraction of an obtrusive experimental score ... frequently makes it impossible to comprehend mere dialogue".[23] Time magazine's Richard Corliss wrote, "In one sense, then, Rumble Fish is Coppola's professional suicide note to the movie industry, a warning against employing him to find the golden gross. No doubt: this is his most baroque and self-indulgent film. It may also be his bravest."[24]

Jay Scott wrote one of the few positive reviews for the film in The Globe and Mail. "Francis Coppola, bless his theatrical soul, may have the commercial sense of a newt, but he has the heart of a revolutionary, and the talent of a great artist."[25] Jack Kroll also gave a rare rave in his review for Newsweek: "Rumble Fish is a brilliant tone poem ... Rourke's Motorcycle Boy is really a young god with a mortal wound, a slippery assignment Rourke handles with a fierce delicacy."[26] The film has a 71% rating on Rotten Tomatoes and a 63 metascore on Metacritic. David Thomson has written that Rumble Fish is "maybe the most satisfying film Coppola made after Apocalypse Now".[27]

Despite mixed reviews, Rumble Fish won the highest prize in the 32nd San Sebastián International Film Festival, the International Critics' Big Award.[28]

Home media

The film was first released on VHS in 1984 and on DVD on September 9, 1998 with no extra material. A special edition was released on September 13, 2005 with an audio commentary by Coppola, six deleted scenes, a making-of featurette, a look at how Copeland's score was created and the "Don't Box Me In" music video. In August 2012, The Masters of Cinema Series released a special Blu-ray edition of the film (and accompanying Steelbook edition) in the UK.

Cultural impact

Rumble Fish was a source of inspiration for the Welsh alternative rock band, the Manic Street Preachers. The Manics' song "Spectators of Suicide" was originally titled "Colt 45 Rusty James." (A demo version is included on the 2012 re-release of Generation Terrorists under the title "Colt 45.") The Manics have also cited Rumble Fish as an influence on their song "Motorcycle Emptiness".

References

- ^ a b Rumble Fish at Box Office Mojo

- ^ The 1980s device is not to be confused with the 21st-century music licensing company of the same name. "Stewart Copeland interview excerpt,". Rock World magazine. May 1984. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- ^ a b Chown 1988, p. 169.

- ^ a b Chown 1988, p. 168.

- ^ a b Goodwin 1989, p. 347.

- ^ a b c d e f Goodwin 1989, p. 349.

- ^ Cowie 173.

- ^ a b Goodwin 1989, p. 350.

- ^ a b Goodwin 1989, p. 351.

- ^ a b Reveaux, Anthony (May 1984). "Stephen H. Burum, ASC and Rumble Fish". American Cinematographer. p. 53.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Reveaux May 1984, p. 56.

- ^ Cowie 171.

- ^ a b c Goodwin 1989, p. 348.

- ^ ASC 1982.

- ^ Chown 1988, p. 171.

- ^ Chown 1988, p. 172.

- ^ Chown 1988, p. 170.

- ^ Scott, "Loving, Ferocious Depiction of Teen Angst," E7.

- ^ "Rumble Fish". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Chown 1988, p. 167.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (October 7, 1983). "Matt Dillon is Coppola's Rumble Fish". The New York Times.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Ebert, Roger (August 26, 1983). "Rumble Fish". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Arnold, Gary (October 18, 1983). "Bungled Rumble". Washington Post. pp. D3.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Corliss, Richard (October 24, 1983). "Time Bomb". Time. Retrieved 2009-02-18.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Scott, Jay (October 14, 1983). "Loving, Ferocious Depiction of Teen Angst". The Globe and Mail. pp. E7.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Kroll, Jack (November 7, 1983). "Coppola's Teen-Age Inferno". Newsweek. p. 128.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Thomson, David (2008). "Have You Seen . . . ?": A Personal Introduction to 1,000 Films. Knopf. p. 743. ISBN 978-0-307-26461-9.

I don't mean to overpraise Rumble Fish, but I think it is a haunting evocation of teenage years and maybe the most satisfying film Coppola made after Apocalypse Now.

- ^ "Archive of awards, juries and posters". San Sebastian International Film Festival. 1984. Retrieved 2008-12-30.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help)

Further reading

- Chown, Jeffrey. Hollywood Auteur: Francis Coppola. New York: Praeger, 1988.

- Cowie, Peter. Coppola. Suffolk: St. Edmundsbury, 1989.

- A Conversation With Stephen Burum, ASC. International Cinematographers Guild.

- Goodwin, Michael, and Naomi Wise. On the Edge: The Life and Times of Francis Coppola. New York: Morrow, 1989.

External links

- 1983 films

- 1980s drama films

- American films

- American teen drama films

- English-language films

- Films directed by Francis Ford Coppola

- American black-and-white films

- Films about siblings

- Films based on American novels

- Films set in Tulsa, Oklahoma

- Films set in Oklahoma

- Films shot in Oklahoma

- American gang films

- Southern Gothic films

- American Zoetrope films

- Universal Pictures films

- Screenplays by Francis Ford Coppola

- Film scores by Stewart Copeland