Harvard, Massachusetts

Harvard, Massachusetts | |

|---|---|

The renovated library, established in 1856 | |

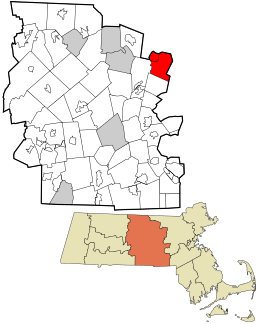

Location in Worcester County and the state of Massachusetts. | |

| Coordinates: 42°30′00″N 71°35′00″W / 42.50000°N 71.58333°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Massachusetts |

| County | Worcester |

| Settled | 1658 |

| Incorporated | 1732 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Open town meeting |

| • Town Administrator | Timothy P. Bragan |

| • Select Board |

|

| Area | |

• Total | 27.0 sq mi (69.9 km2) |

| • Land | 26.4 sq mi (68.3 km2) |

| • Water | 0.6 sq mi (1.6 km2) |

| Elevation | 420 ft (128 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 6,851 |

| • Density | 250/sq mi (98/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP code | 01451 |

| Area code | 351 / 978 |

| FIPS code | 25-28950 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0619482 |

| Website | www.harvard.ma.us |

Harvard is a town in Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. The town is located 25 miles west-northwest of Boston, in eastern Massachusetts. It is mostly bounded by I-495 to the east and Route 2 to the north. A farming community settled in 1658 and incorporated in 1732, it has been home to several non-traditional communities, such as Harvard Shaker Village and the utopian transcendentalist center Fruitlands. It is also home to St. Benedict Abbey, a traditional Catholic monastery, and for over seventy years was home to Harvard University's Oak Ridge Observatory, at one time the most extensively equipped observatory in the Eastern United States.[1] It is now a rural and residential town noted for its public schools.[2] The population was 6,851 at the 2020 census.[3]

History

[edit]Europeans first settled in what later became Harvard in the 17th century, along a road connecting Lancaster with Groton that was formally laid out in 1658. They settled on land purchased from Nashaway sachems Sholan and his nephew George Tahanto.[4] There were few inhabitants until after King Philip's War, in which Groton and Lancaster were attacked and substantially destroyed. Over the next 50 years the population grew until it had reached a point adequate to support a church. A new town including parts of Lancaster, Groton, and Stow was incorporated in 1732, subject to the proviso that the inhabitants "Settle a learned and Orthodox Minister among them within the space of two years and also erect an House for the publick Worship of God." It is uncertain how the town obtained its name, though the Willard family, among the first settlers and the largest proprietors in the new town, had several connections to Harvard College.[5] According to The Harvard Crimson, Josiah Willard named the town after Harvard College, which he had attended, because the articles of incorporation had left the town unnamed.[6] The first minister was Rev. John Seccombe, serving from 1733 to 1757.[7]

In 1734, the town was considered to have five districts or villages. These were Oak Hill, Bare Hill, Still River, Old Mill, and Shabikin, present day Devens.

One notable early enterprise based in Harvard was the Benjamin Ball Pencil Company,[8] which produced some of the first writing instruments made in the United States. They operated in the Old Mill district from 1830 to 1860. Despite this and other limited manufacturing, the town economy was primarily based on agriculture until the middle of the 20th century. This past is most prominently visible in the number of apple orchards. These apple orchards produce many apple products every year the most notable being apple cider. It is now mostly a residential "bedroom community" for workers at companies in Boston and its suburbs. Harvard has had a relatively quiet history, but has attracted several "non-traditional" communities that have given its history some flavor.

The Shakers

[edit]One part of town is the site of Harvard Shaker Village, where a utopian religious community was established. During a period of religious dissent, a number of Harvard residents, led by Shadrack Ireland, abandoned the Protestant church in Harvard. In 1769, they built a house that later became known as the Square House. Not long after Ireland's death in 1778, the Shaker Founder Mother Ann Lee met with this group in 1781 and the group joined her United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing, or Shakers.[9]

It was the first Shaker settlement in Massachusetts and the second settlement in the United States. The Harvard Shaker Village Historic District is located in the vicinity of Shaker Road, South Shaker Road, and Maple Lane. At its largest, the Shakers owned about 2,000 acres of land in Harvard. By 1890, the Harvard community had dwindled to less than 40, from a peak of about 200 in the 1850s. In 1917 the Harvard Shaker Village was closed and sold. Only one Shaker building is open to the public, at Fruitlands Museum; the remaining surviving buildings are in private ownership.[9]

Nationally, 19 Shaker communities had been established in the 1700s and 1800s, mostly in northeastern United States. Community locations ranged from Maine to Kentucky and Indiana. The Shakers were renowned for plain architecture and furniture, and reached its national peak membership in the 1840s and 1850s. The Shaker community's practice of celibacy meant that to maintain its population, it was always necessary to have new outsiders join. The improving employment opportunities provided by the Industrial Revolution would over the middle decades of the 1800s diminish the attractions of joining the Shaker community. Today, only one church "society" remains open, run by the last Shakers at Sabbathday Lake Shaker Village in New Gloucester, Maine.

Fruitlands

[edit]

Amos Bronson Alcott relocated his family, including his ten-year-old daughter, Louisa May Alcott, to Harvard in June 1843. He and Charles Lane attempted to establish a utopian transcendentalist socialist farm called Fruitlands on the slopes of Prospect Hill in Harvard. The experimental community only lasted 7 months, closing in January 1844. Fruitlands, so called "because the inhabitants hoped to live off the fruits of the land, purchasing nothing from the outside world",[10] saw visits from the likes of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson.[11] Louisa May Alcott used her experience at Fruitlands as an inspiration for her novel Little Women.[10]

Clara Endicott Sears, whose Prospect Hill summer estate, The Pergolas,[11] restored Fruitlands and opened it as a museum in 1914.[10] On the grounds of Fruitlands Museum there is also a Shaker house, which was relocated there from Harvard's Shaker Village by Sears in 1920. It is the first Shaker museum ever established in the United States.[11] In addition, Sears opened a gallery on the property dedicated to Native American history. Sears became interested in Native Americans after Nipmuck arrowheads were found around her property on Prospect Hill, which the Nipmuck Indians had called Makamacheckamucks.[12]

Originally, Sears' Fruitlands property spanned 458 acres (1.85 km2), but in 1939, 248 acres (1.00 km2) were seized by eminent domain for expansion of Fort Devens. As of 2010, that land is now part of the Oxbow National Wildlife Refuge.[10]

Fiske Warren Tahanto Enclave

[edit]Fiske Warren, a follower of Henry George, attempted to establish a single tax zone in Harvard in 1918. The enclave bought up land (previously owned by the recently disbanded Shaker community) communally and attempted to manage the land according to George's principles. The enclave disbanded shortly after Warren died in 1938. His house was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1996.

St. Benedict Center

[edit]Father Leonard Feeney was a Jesuit priest who held to a literal interpretation of the doctrine "Extra Ecclesiam nulla salus" (or "outside the Church there is no salvation"). Feeney was excommunicated in 1953. Under the direction of Feeney, Catherine Goddard Clarke and others organized into a group called the Slaves of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, an unofficial Catholic entity. In January 1958, the community moved from Cambridge to the town of Harvard. Eventually, the original community split into several groups: the Benedictines, the Sisters of Saint Ann's House and Sisters of St. Benedict's center, Slaves of the Immaculate Heart of Mary. A further split later occurred with some members of the Slaves of the Immaculate Heart of Mary leaving to establish a separate group in New Hampshire. A branch of the Saint Benedict Center[13] is located in Still River, on the west side of Harvard.

St. Benedict Abbey

[edit]In Still River there is an abbey of Benedictine monks that branched from the St. Benedict Center. They focus on reverently saying Mass in both in English and Latin in the post-Vatican II form and chanting the Divine Office in Latin.[14] Their current abbot is the Right Reverend Marc Crilly, OSB, who was elected May 15, 2021.[15]

Geography

[edit]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the town has a total area of 27.0 square miles (70 km2), of which 26.4 square miles (68 km2) is land and 0.6 square miles (1.6 km2), or 2.26%, is water.

The eastern part of Harvard is on a large ridgeline. In 1931 Harvard College established the Oak Ridge Observatory at an elevation of 609 feet on Pinnacle Rd, the highest point between Mount Wachusett and the ocean.[16][17]

Harvard is largely wooded with rolling hills, fields, and wetlands. In addition to numerous streams and brooks, Bare Hill Pond, a 320-acre lake with its town beach, dock, and several small islands, is a central, iconic locale.[18][19]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 1,630 | — |

| 1860 | 1,507 | −7.5% |

| 1870 | 1,341 | −11.0% |

| 1880 | 1,253 | −6.6% |

| 1890 | 1,095 | −12.6% |

| 1900 | 1,139 | +4.0% |

| 1910 | 1,034 | −9.2% |

| 1920 | 2,546 | +146.2% |

| 1930 | 987 | −61.2% |

| 1940 | 1,790 | +81.4% |

| 1950 | 3,983 | +122.5% |

| 1960 | 2,563 | −35.7% |

| 1970 | 12,494 | +387.5% |

| 1980 | 12,170 | −2.6% |

| 1990 | 12,329 | +1.3% |

| 2000 | 5,981 | −51.5% |

| 2010 | 6,520 | +9.0% |

| 2020 | 6,851 | +5.1% |

| 2023* | 6,928 | +1.1% |

| * = population estimate. Source: United States census records and Population Estimates Program data.[20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30] | ||

As of the census[31] of 2000, there were 5,981 people, 1,809 households, and 1,494 families residing in the town. The population density was 226.9 inhabitants per square mile (87.6/km2). There were 2,225 housing units at an average density of 84.4 per square mile (32.6/km2). The racial makeup of the town was 91.69% White, 4.50% African American, 0.17% Native American, 1.97% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 0.50% from other races, and 1.12% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 6.09% of the population.

There were 1,809 households, out of which 44.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 73.4% were married couples living together, 6.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 17.4% were non-families. 14.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 4.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.86 and the average family size was 3.18.

In the town the population was spread out, with 26.6% under the age of 18, 4.0% from 18 to 24, 29.5% from 25 to 44, 32.3% from 45 to 64, and 7.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 41 years. For every 100 females there were 124.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 133.6 males.

The median income for a household in the town was $117,934, and the median income for a family was $139,352. Males had a median income of $90,937 versus $49,318 for females. The per capita income for the town was $50,867. About 0.5% of families and 2.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 0.7% of those under age 18 and 7.1% of those age 65 or over.

The decline in the population of the town of Harvard from the 1990 census to the 2000 U.S. census is attributable to the 1996 closure of Fort Devens, a U.S. military installation and the departure of military personnel and families residing at Fort Devens, which in large part is within the territory of the town of Harvard. The Fort Devens property has in large part been converted to civilian use, under the direction of MassDevelopment, a development authority of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Arts and culture

[edit]

The public library of Harvard opened in 1856.[32][33] The official seal of the town depicts the old town public library on The Common prior to renovations that removed the front steps. In fiscal year 2008, the town of Harvard spent 2.41% ($487,470) of its budget on its public library—approximately $81 per person and since then the library has undergone multiple renovations.[34]

Government

[edit]The town elects five members to the Board of Selectmen to run the town day-to-day and has an annual Town Meeting to pass/amend the town bylaws and approve the town budget.

Education

[edit]Harvard houses three public schools. In the center of town is Hildreth Elementary, and a middle/high school, The Bromfield School. These schools are highly rated within Massachusetts and the nation.[2] In Devens, there is the Francis W. Parker Charter School. In Still River, there is the Immaculate Heart Of Mary, a private traditional Catholic school for Grades 1–12.[35]

When the town constructed the current building housing the Bromfield School middle and high school, the town successfully resisted the Massachusetts School Building Authority efforts to regionalize its school system with other towns; the School Building Authority partially funds new school buildings and renovations.

Notable people

[edit]- Amos Bronson Alcott, teacher, writer and Transcendentalist, Fruitlands founder

- Louisa May Alcott, novelist, daughter of Amos Alcott

- Cornelius Atherton, inventor and steel maker. Blacksmith, built muskets for the Revolutionary Army

- Peter Atherton, 18th-century colonial leader

- Simon Atherton, early American Shaker who sold herbs in and around Boston

- Tabitha Babbitt, tool maker

- T. A. Barron, author of fantasy novels

- Del Cameron, Hall of Fame harness racing driver and trainer[36]

- Theodore Ward Chanler, American composer

- Adam Dziewonski, geophysicist

- Jonathan Edwards, musician[37]

- William Emerson, minister and father of Ralph Waldo Emerson

- Fannie Farmer, cookbook author

- Donald Featherstone, created the plastic flamingo lawn ornament

- Leonard Feeney, controversial Jesuit priest and founder of St. Benedict Center

- Levi Hutchins, clockmaker, inventor of the American alarm clock

- Shadrack Ireland, religious leader

- Lynn Jennings, Olympic runner

- Charles Lane, Transcendentalist, Fruitlands founder

- George F. Lewis, proprietor of newspapers

- Keir O'Donnell, Australian-born actor, Bromfield Class of 1996

- Joseph Palmer, Transcendentalist; known for his beard

- Willard Van Orman Quine, American philosopher and logician[38]

- Clara Endicott Sears, founder of Fruitlands Museum

- John Seccombe, religious leader, author

- Ted Sizer, educational reform leader[39]

- Maurice K. Smith, architect

- Otto Thomas Solbrig, Renowned biologist [40]

- Michael L. Taylor, military veteran

- Fiske Warren, supporter of Henry George's land value tax or single tax system

- William Channing Whitney, architect

- Gary K. Wolf, creator of Roger Rabbit

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Oak Ridge Station". Harvard University Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments. Archived from the original on October 3, 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ^ a b "Best High Schools in the U.S." U.S. News & World Report. 2023. Archived from the original on September 27, 2023. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ^ "Census - Geography Profile: Harvard town, Worcester County, Massachusetts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2021.

- ^ The Story of Colonial Lancaster, p. 3, 60-61 https://ia601009.us.archive.org/31/items/storyofcoloniall00saff/storyofcoloniall00saff.pdf (accessed 3/30/24)

- ^ Nourse, pp. 58-60.

- ^ "'Harvard' Is More Than A University | News | The Harvard Crimson". www.thecrimson.com. Archived from the original on February 27, 2023. Retrieved February 27, 2023.

- ^ "History of Worcester County, Massachusetts, Embracing a ..., Volume 1 By Abijah Perkins Marvin, p.559". 1879. "Father%20Abbey's%20will"&f=false Archived from the original on February 6, 2022. Retrieved February 6, 2022.

- ^ "Pencils". Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved August 13, 2017.

- ^ a b "Harvard Shaker Village Historic District". National Park Service. n.d. Archived from the original on September 26, 2013. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Fruitlands Museum Archived 2011-10-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Patricia Harris, Anna Mundow, David Lyon, James Marshall, Lisa Oppenheimer. Compass American Guides: Massachusetts, 1st Edition. Random House. 2003. Pg. 186.

- ^ Kinnicutt, Lincoln Newton. Indian Place Names in Worcester County Massachusetts. Common Wealth Press. 1905. Pg. 20.

- ^ "Our History". Sisters of Saint Benedict Center. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved June 22, 2008.

- ^ A guide to religious Ministries, 2010 edition

- ^ Abbot Xavier Biography Archived 2011-10-05 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 22 Nov. 2010

- ^ "Oak Ridge Station". Harvard University Collection of Historical Scientific Instruments Science Center. Archived from the original on October 3, 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ^ "Old Eyes on the Sky". Space.com. Archived from the original on June 7, 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ^ "Bare Hill Pond: A Hidden Gem". Town of Harvard. Archived from the original on June 15, 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ^ "Bare Hill Pond". MassachusettsPaddler.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2023. Retrieved October 1, 2023.

- ^ "Total Population (P1), 2010 Census Summary File 1". American FactFinder, All County Subdivisions within Massachusetts. United States Census Bureau. 2010.

- ^ "Massachusetts by Place and County Subdivision - GCT-T1. Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1990. Table 76: General Characteristics of Persons, Households, and Families: 1990. 1990 CP-1-23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1980 Census of the Population, Number of Inhabitants: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1981. Table 4. Populations of County Subdivisions: 1960 to 1980. PC80-1-A23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21-10 and 21-11, Massachusetts Table 6. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1930 to 1950. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1920 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. Number of Inhabitants, by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions. Pages 21-5 through 21-7. Massachusetts Table 2. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1920, 1910, and 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1890 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. Pages 179 through 182. Massachusetts Table 5. Population of States and Territories by Minor Civil Divisions: 1880 and 1890. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1870 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1872. Pages 217 through 220. Table IX. Population of Minor Civil Divisions, &c. Massachusetts. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1860 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1864. Pages 220 through 226. State of Massachusetts Table No. 3. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1850 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1854. Pages 338 through 393. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "City and Town Population Totals: 2020−2023". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 1, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ C.B. Tillinghast. The free public libraries of Massachusetts. 1st Report of the Free Public Library Commission of Massachusetts. Boston: Wright & Potter, 1891. Google books Archived January 9, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ http://www.harvardpubliclibrary.org/ Archived August 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2010-11-10

- ^ July 1, 2007 through June 30, 2008; cf. The FY2008 Municipal Pie: What's Your Share? Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Board of Library Commissioners. Boston: 2009. Available: Municipal Pie Reports Archived 2012-01-23 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2010-08-04

- ^ "School 7 District Profiles". doe.mass.edu. Archived from the original on June 15, 2021. Retrieved September 29, 2023.

- ^ "Adelbert 'Del' Cameron page at Harness racing Museum & Hall of Fame". Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- ^ Pollack, Bruce (July 9, 2013). "Jonathan Edwards - "Sunshine"". Songfacts. They're Playing My Song. Archived from the original on July 22, 2013. Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- ^ Føllesdal, Dagfinn (March 2, 2001). "Quine Memorial Forum". Harvard Review of Philosophy: 106–111. doi:10.5840/harvardreview2001919. Archived from the original on January 29, 2022. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ Fox, Margalit (October 22, 2009). "Theodore R. Sizer, Leading Education-Reform Advocate, Dies at 77". New York Times. Archived from the original on March 31, 2011. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ^ "Otto T. Solbrig". Archived from the original on May 31, 2023. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Nourse, Henry S. (1894). History of the Town of Harvard, Massachusetts 1732-1893. Clinton, Massachusetts: Warren Hapgood. Retrieved July 7, 2011.

- Anderson, Rober C. (1976). Directions of a town: a history of Harvard, Massachusetts. Harvard, Massachusetts: Harvard Common Press.