Pride Quarter, Liverpool

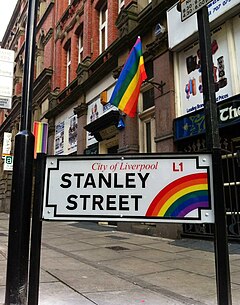

One of the rainbow street signs, located on Stanley Street. | |

| Location | Liverpool City Centre, Liverpool, UK |

| Postal code | L1/L2 |

| Coordinates | 53°24′26″N 2°59′13″W / 53.40722°N 2.98694°W |

| North | Dale Street |

| East | Cumberland Street |

| South | Victoria Street |

| West | Eberle Street |

| Other | |

| Known for | LGBT community, Gay bars & clubs, Gay clubbing, Liverpool Pride |

The "Stanley Street Quarter"[1] (sometimes Liverpool Gay Quarter or Village) is an area within Liverpool City Centre, England, which serves as the main focal point for Liverpool's lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community. It is made up of mixed use developments including residential blocks, hotels, bars, nightclubs and various other businesses, many of which cater for the LGBT community. The quarter is also one of the sites where the annual Liverpool Pride is held.

The neighbourhood encompasses Stanley Street, Davies Street, Cumberland Street, Sir Thomas Street, Dale Street, Temple Street & Lane, Victoria Street, Hackins Hey, Leather Lane and Eberle Street. Stanley Street has often been seen as the symbolic heart of the 'gay quarter' and is where a large number of the bars are found.

On 12 August 2011, Liverpool City Council officially recognised the area as the city's 'gay quarter',[2] and on 6 December 2013, City Council Cabinet members took the decision to endorse a dedicated Community interest company to further the development of the quarter and access funding which the local authority would otherwise be unable to. It will become active from the beginning of 2014.

History of LGBT Liverpool

Victorian Criminalisation to Queen Square

In keeping with Liverpool's history as a major seafaring port, the local gay community can be traced as far back as the Victorian era. Whilst in the past research into this area has been limited and scarce, interest has grown considerably in recent times.

In his 2011 lecture 'Policing Sex Between Men: 1850-1971', historian Jeff Evans examined 70,000 criminal records dating back to 1850 and was able to shed light on hundreds of records of men prosecuted under the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885 (the law used to prosecute Oscar Wilde) found in the court papers of Liverpool and North West England.[3][4][5]

The legacy of Victorian laws and homosexual criminalisation meant that the city's lesbian and gay community would be largely underground for the next century and little is known about it during this period. However, recent research has highlighted the existence of an unofficial gay quarter around Queen Square from as early as the 1940s, which earned itself the nickname "Covent Garden of the North".[6] Although gay sex between consenting adults was not legalised until 1967, the gay community enjoyed relative acceptance in this area and establishments such as the Stork Hotel, the Roebuck, Spanish House, Magic Clock, Royal Court, and The Dart all boasted a substantial gay clientele, albeit liaisons were still held in secret to a degree.[7][8] By the early 1970s, a gay society named 'The Homophile Society', which campaigned for homosexual equality, was formed at the University of Liverpool.[9]

Queen Square to Stanley Street

The building of the new St. John's Shopping Centre and subsequent demolition of the original Queen Square meant the gay community was forced to find a new home and by 1972, with the opening of Paco's, the community had now began to settle around Stanley Street in what was to develop into Liverpool's modern day Gay Quarter.[10]

Timeline of Liverpool's Gay Scene

| Date | Sequence of Events | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| 1940s - 1960s | Queen Square the centre of Liverpool's original gay quarter | [11][12] |

| 1960s - 1970s | Building of St. John's Shopping Centre marks beginning of decline for original gay scene. Landscape of Queen Square changed as Roe Street Gyratory and bus station opens. Original gay bar, The Stork, is demolished in 1975. | [13] |

| 1970s - 1980s | Critical mass of gay venues now centred on Stanley Street. Opening of several gay establishments in the area including Jody's, The Curzon, The Lisbon, and Paco's. First recorded Liverpool Gay Pride Festival took place in 1979. | [14][15][16] |

| 10 Dec 2009 | Stanley St/Cumberland St/Eberle St are pedestrianised at night | [17] |

| 7 Aug 2010 | City's first "Official" Pride festival held in the Gay Quarter | [18] |

| February 2011 | Plans to revamp gay quarter unveiled by Liverpool City Council | [19] |

| 6 Aug 2011 | Main focus of Liverpool Pride is relocated to Pier Head. G-Bar, Garlands, and the informal Liverpool Gay Business Association organise first ever independent Gay Quarter Pride to complement existing celebrations | [20][21] |

| 12 Aug 2011 | Liverpool City Council officially recognises Gay Quarter as a distinct city centre district. Plans to revamp the area are approved | [22] |

| 11 Nov 2011 | Liverpool becomes the first British city to install rainbow street signs identifying the Gay Quarter | [23] |

| 6 Dec 2013 | Liverpool City Council cabinet members endorse the creation of the Stanley Street Quarter Community Interest Company | [24] |

Further Research

Research into Liverpool's gay past took a significant turning point in 2004 as part of the inaugural Homotopia celebrations, the city's home grown gay arts festival. A major project titled 'Tales From Yester-Queer' organised in conjunction with The Armistead Project, Unity Theatre and Liverpool Record Office, became the first ever attempt to pay tribute to the experiences of older lesbian and gay Liverpudlians. The project involved collecting and collating various spoken, written and video sources, as well as a short film commission 'Gayzin Liverpool', produced by local filmmaker Sandi Hughes.[25][26][27]

The event became the catalyst for a major public perspective of gay and lesbian Liverpool and shortly followed was 'Our Story Liverpool', an oral history resource which recorded the experiences of community members from the 1930s to the present day.[28][29]

A similar and more recent project titled "Pink: Past & Present" has also explored the rich lesbian and gay history of the city[30] which had its world premier in November 2010.[31][32]

Present Day Gay Quarter

Pedestrianisation

In June 2008, Liverpool City Council launched a Public consultation on the partial pedestrianisation of streets in the gay quarter, with a view to enhancing the night time leisure experience of the area.[33] The council had originally proposed to restrict traffic in Stanley Street, Cumberland Street and Eberle Street after 6pm with the use of automatic hydraulic bollards at strategic locations.

After concerns were raised over restricted access to the streets by some businesses in the area, the City Council proposed to reduce hours of street closure and held a second consultation in November 2008.[34] It was decided that reduced hours of street closure would be a compromise to accommodate deliveries to some day-time businesses in the area. [citation needed]

As a result of campaigns from the LGBT community, the Council held a third consultation between Friday 23 January 2009 and Friday 20 February 2009, and proposed longer hours of pedestrianisation. After analysing public opinion, the City Council decided that hours proposed the third time round were insufficient in ensuring pedestrian safety.

A fourth and final consultation was held in September 2009 and no objections from the public were lodged.[35]

Liverpool's gay quarter was finally pedestrianised on 10 December 2009. Stanley Street is now closed to traffic between 10pm-6am seven days of the week, Cumberland Street is closed between 6pm-6am seven days of the week, and Eberle Street is closed for 24 hours of the day seven days of the week.[36] This will be further reviewed in 2014 as part of a public consultation on the future aspirations of the area led by the new Community Interest Company

Thanks to pedestrianisation and a cooperative effort to promote the Stanley Street quarter to shoppers and tourists, a number of day time community events were launched in 2012 including Mother's Day celebrations, an Arts & Literature Day, and a series of monthly markets with street entertainment and pavement cafes.[37]Template:PDFlinkTemplate:PDFlink

Ongoing Redevelopment

Initial plans to revamp Liverpool's gay quarter were unveiled in February 2011 after detailed consultation with the public and stakeholders. City leaders believe a vibrant gay village around Stanley Street is key to the future economic success of Liverpool city centre as an international tourist destination. Urban planner Feria Urbanism carried out a £12,000 study in conjunction with the City Council[38] to formulate a vision for the gay quarter to put it on a par with the best in the UK.[39] The company is consulted with businesses and residents in the area to see how public areas and safety can be improved. With the founding of the new Community Interest Company the area's steering group recognised that there was a need to refresh this strategy and an update, looking in more detail at platemaking is expected to be launched in May 2014, in time for the International Festival for Business 2014.

Cllr Nick Small, cabinet member for employment and skills, said: "We have made strides in recent years and are being seen as a more gay-friendly city than was the case a few years ago. We now need to look at how we can develop and promote the quarter."[40]

As a result of this report in 2011, numerous regeneration options for the Stanley Street quarter were under discussion and include new rainbow coloured paving, artworks, gateway features, street-tree planting, new outdoor seating and street furniture, and a new public square.Template:PDFlink A consultation on Feria Urbanism's draft report titled "Stanley Street: Strategic direction for a vital urban quarter (May 2011)" has taken place. Suggestions for which organisations and stakeholders should take responsibility for proposed actions and recommendations have also been made, and it is envisaged that initial stages of regeneration should take place over the next 2–5 years, with a longer term vision.[41] As part of the first phase of redevelopment, Liverpool became the first city in the UK to install street signage bearing the rainbow coloured Gay Pride flag on 11 November 2011. The signage identifies the city's Gay Quarter located on Stanley Street, Cumberland Street, Temple Lane, Eberle Street and Temple Street.[42]

Following the announcement of redevelopment plans for Liverpool's Gay Quarter, several other British cities have called for similar initiatives in their local area. A delegation from West Yorkshire visited Liverpool in March 2012 to learn from the city's experience with a view to establishing an official gay area based on The Calls and Lower Briggate district of Leeds.[43] Campaigners in the city of Brighton and Hove are also now calling for their gay district to be officially recognised.[44]

Community Interest Company

In December 2013, Liverpool City Council approved the formation of a dedicated firm to help attract investment into and improve the quarter. The Stanley Street QuarterCommunity interest company will be registered in time for 2014. The move builds on work that has taken place since 2011 including the setting up of a steering group involving councillors and representatives of the quarter, which has looked at ways of boosting the village’s image as a local, national and international visitor destination. The new company will actively seek to involve stakeholders and the public in its efforts to develop the area, including reserved places on the 'Board of Directors' for local businesses and interested members of the public.[45][46]

Destination

VisitBritain, Britain's national tourism agency, acknowledges Liverpool as one of Britain's most notable gay cities, and recognises the growing investment in the Gay Quarter.[47][48] Liverpool City Council hopes that further investment, including partial pedestrianisation will further promote Liverpool as a gay destination.[49] In a similar fashion to most other major British cities, the gay scene of Liverpool is fast changing with several bars and clubs often changing in ownership and offer, but there are roughly a dozen night time establishments operating in the quarter at any given time within a 200-metre (one eighth of a mile) radius of Stanley Street. There are also numerous other gay frequented venues dotted elsewhere around the city centre.[50][51] The oldest and longest running venue is The Curzon which opened its doors as a predominantly gay men's bar in 1988,[52][53] although it is often contested that the oldest venue is in fact The Lisbon which has claimed a considerable gay following since well before the 1970s.[9][54][55]

LGBT Culture in Liverpool

Research commissioned by the North West Regional Development Agency approximated that there were around 94,000 LGBT persons living in Liverpool's metropolitan area by mid 2009 Template:PDFlink - equivalent to the GLB population of San Francisco Template:PDFlink

Crime

In recent years, a series of attacks have resulted in a call for increased police protection in the quarter. Perhaps the most high profile attack was that of James Parkes, an off-duty trainee police officer, who was set upon by up to 20 teenage thugs in a homophobic attack outside the well known gay club Superstar Boudoir on Stanley Street in October 2009. Multiple skull fractures, a fractured eye socket and a fractured cheek bone left the officer fighting for his life.[56] In May 2011, drag artist Lady Shaun suffered a broken jaw after being knocked out by a man who punched her in the face, whilst just two weeks earlier, 21-year-old choreographer Calvin Fox was assaulted by two people on his way home after a night out. In September the same year, two separate attacks in the gay quarter left two young men with serious head and facial injuries. Local authorities acknowledged there was indeed an increase in "homophobic" crime. Openly gay Councillor Steve Radford said, "Liverpool has a long way to travel in its journey to become a gay-friendly city". Chief Inspector Louise Harrington commented, "We have to strike a balance between a heavy police presence which could scare people off and those that say it makes them feel safer."[57][58] Liverpool City Council have been working for some time to improve the safety of the area, particularly after dark; Several community safety initiatives are due to be completed by late January 2014 including a high-volume, marshalled Taxi Rank and the installation of gates on Progress Place, a section of Private Land off Stanley Street where many of the attacks in the area have been linked as well as antisocial behaviour.

Liverpool Pride

Up until 2010, Liverpool was the largest British city to not hold a Pride festival. However on 7 August 2010, the city's first "Official" Pride festival (officially sponsored by Liverpool City Council and public authorities), attracted an audience of over 21,000, the majority of whom came from outside the city. The festival took place around the city's Gay Quarter with stages on Dale Street, Exchange Flags, and North John Street, and a city centre march was held during the day. Organisers hailed the festivities a massive success and now plan to hold larger events in the future [59] At Liverpool Pride 2011, it was announced that visitor numbers had doubled to over 40,000.[60] On 11 March 2011, Liverpool Pride became a registered charity.[61] In 2012 Liverpool Football Club were the first Premier League team to publicly support a Pride event with members of staff and fans marching in the parade with a banner provided by the club.[62]

References

- ^ "Stanley Street quarter can boost city economy - Liverpool City Council". Liverpool.gov.uk. 4 August 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "BBC News - Liverpool gay quarter gets go-ahead". Bbc.co.uk. 12 August 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ Yakub Qureshi (19 February 2011). "Secret's out on the hidden life of gay Victorians | Manchester Evening News". menmedia.co.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Policing Sex Between Men : 1850-1971". Homotopia.net. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Homotopia 2011 | News Articles | News | Home". Lgf.org.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ Davis, Laura. "Exhibition of photos of Gay Liverpool on display at 3345 as part of Pride - Liverpool Arts - Culture". Liverpool Daily Post. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "icLiverpool - A view of the Wilde side of life". Icliverpool.icnetwork.co.uk. 1 November 2005. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ Davis, Laura. ""Exhibition of photos of Gay Liverpool on display at 3345 as part of Pride", Liverpool Daily Post, 4th August 2010". Liverpooldailypost.co.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ a b http://www.liv.ac.uk/lgbt-history/PINK%20BRICk%20LGBT%20Histories%20TIMELINE.pdf

- ^ "Seen Magazine, November 2010, Page 38". Issuu.com. 2 November 2010. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ ""The full Pete Price: Day 3 - Being Gay", Liverpool Echo, 26th September 2007". Liverpoolecho.co.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Neighbourhoods - The Beat Goes Online". Liverpool museums. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ ""Flashback: A time when Queen Square was Liverpool's unofficial gay quarter", Liverpool Echo, 24th July 2010". Liverpoolecho.co.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ [1]

- ^ "BBC - Liverpool's journey to Gay Pride". BBC News. 11 June 2010. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Nerve 13 - 2009". Catalystmedia.org.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ Schofield, Ben (8 December 2009). ""Bollards to stop cars entering Liverpool's gay quarter", Liverpool Daily Post, 8th December 2009". Liverpooldailypost.co.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Liverpool's first ever official Pride festival takes place this weekend > Culture > Culture". Click Liverpool. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Find and review gay friendly accommodation around the world". OutGuider. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ ""Pride Fringe", OutGuider, 22nd February 2011". Liverpoolpride.co.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ Peter Lloyd (1 August 2011). "TRAVEL: Going to Liverpool Pride?". News.pinkpaper.com. Archived from the original on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ Jonny Payne (13 August 2011). "Liverpool granted permission to develop a new gay quarter - PinkPaper.com". News.pinkpaper.com. Archived from the original on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ Jonny Payne (12 November 2011). "Liverpool becomes the first UK city to have gay street signs - PinkPaper.com". News.pinkpaper.com. Archived from the original on 14 July 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ Raziye Akkoc (6 December 2013). "Gay Village Company Gets Go Ahead - Liverpool Echo". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- ^ "City hosts first Homotopia festival". Liverpool 08 Press Releases and archive. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ "Four decades of pride and prejudice: Celebrating and discovering Liverpool's gay past and future". Liverpool Daily Post. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ "OUT AND ABOUT: A cultured tale to tell". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 24 April 2012.

- ^ "Our Story". Issuu.com. 9 December 2009. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "intropage". OurStoryLiverpool. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Liverpool Pink - Past & Present : Homo Heroes!, Lesbian and Gay Foundation, 8th October 2009". Lgf.org.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Pink: Past & Present". First Take. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ "Pink: Past & Present, Homotopia, Liverpool". Homotopia.net. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ Tina Miles (26 June 2008). "Liverpool Echo 26th June 2008". Liverpoolecho.co.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ Schofield, Ben (12 November 2008). "Liverpool Daily Post, 12th November 2008". Liverpooldailypost.co.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ David Bartlett. "'Gay village in Liverpool takes a step closer', Liverpool Echo, 23rd September 2009". Liverpoolecho.co.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ Schofield, Ben (8 December 2009). "'Bollards to stop cars entering Liverpool's gay quarter', Liverpool Daily Post, 8th December 2009". Liverpooldailypost.co.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ Reporter, Staff (4 April 2012). "Food and drink market launched in Liverpool's Stanley Street". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 27 June 2012.

- ^ "BBC News - Liverpool's Stanley Street in gay district study". Bbc.co.uk. 21 February 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ Feria Limited (10 February 2012). "liverpool 02 - w w w . f e r i a - u r b a n i s m . e u". Feria-urbanism.eu. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ Bartlett, David. "Liverpool Echo, 21st February 2011". Liverpoolecho.co.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Liverpool Pride, "Have your say - Stanley St Consultation", 13th April 2011". Liverpoolpride.co.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ Gray, Stephen. "Liverpool unveils UK's first gay street signs". PinkNews.co.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ George Keast (1 March 2012). "Leeds activists meet Liverpool LGBT for tips on gay quarter development success - PinkPaper.com". News.pinkpaper.com. Archived from the original on 12 July 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Calls for Brighton and Hove "gay village" (From The Argus)". Theargus.co.uk. 20 November 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ Raziye Akkoc (6 December 2013). "Liverpool gay village company gets go-ahead". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ "Liverpool's Gay Quarter gets new community interest group". BBC Liverpool. 6 December 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ "Destinations: Explore LGBT Britain". Visit Britain. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ Visit Britain: Explore LGBT Liverpool

- ^ "Liverpool Daily Post 8th September, 2005". Icliverpool.icnetwork.co.uk. 8 September 2005. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Scene Guide". Liverpool Pride. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ http://www.liverpoolvision.co.uk/Docs/DownloadDocs/230Stanley_Street_Final_Report_2011_May_25_WEB_all_pages.pdf

- ^ Lawrence Ferber (25 June 2009). "Curzon Liverpool England". NewNowNext. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Out About: It's 18 Up at Curzon - liverpool echo - February 3, 2006 - Id. 72925150 - vLex". Liverpool-echo.vlex.co.uk. 3 February 2006. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "'I lost my children because I am gay; Emma Johnson talks to the woman who lost a custody battle due to her sexuality', Liverpool Echo, Jun 29th 2011". Thefreelibrary.com. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Seen Magazine, July 2010, Page 16". Issuu.com. 7 July 2010. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Vigils show that the UK will not tolerate homophobia". Pink Paper. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ "Drag queen attacks spark calls for increased safety around Liverpool's Gay Quarter". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ "Two assaults in Liverpool's gay quarter". Pink News. Retrieved 24 May 2012.

- ^ Laura Jones. "'First Liverpool Pride sees 21,000 enjoy gay, lesbian and bisexual festival'". Liverpoolecho.co.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ ""Proud Mersey - Over 40,000 attend Liverpool Pride 2011", Liverpool Pride Website". Liverpoolpride.co.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ "Charity Commission, Charity Number 1140792". Charity-commission.gov.uk. Retrieved 29 March 2012.

- ^ http://www.liverpoolfc.com/news/latest-news/reds-set-for-pride-march

External links

- Stanley Street Quarter official website

- Stanley Street Quarter steering group minutes

- Homotopia (Liverpool's gay arts festival)

- Liverpool Pride

- Liverpool LGBT Network

- Seen Magazine (Liverpool's LGBT Magazine)

- Pink: Past & Present (Liverpool's LGBT history from 1950s to present day

- Our Story Liverpool

- Gay Youth 'R' Out (Local support group for young gay people)

- www.anightinliverpool.com (Gay clubbing & Liverpool nightlife guide)