Staple food

A staple food is one that is eaten regularly and in such quantities that it constitutes a dominant portion of a diet, and that supplies a high proportion of energy and nutrient needs. Most people live on a diet based on at most a small number of staples.[1]

Staple foods vary from place to place, but are typically inexpensive or readily available foods that supply one or more of the three macronutrients needed for survival and health: carbohydrate, protein, and fat. Typical examples include grains, tubers, legumes, or seeds. The staple food of a specific society may be eaten as often as every day, or every meal. Early civilizations valued staple foods because, in addition to providing necessary nutrition, they can usually be stored for a long period of time without decay. Some foods are only staples during seasons of shortage, such as dry seasons or cold-temperate winters, against which times harvests have been stored; during seasons of plenty wider choices of foods may be available.

Most staple foods derive either from cereals such as wheat, barley, rye, maize, or rice, or starchy tubers or root vegetables such as potatoes, yams, taro, and cassava.[2] Other staple foods include pulses (dried legumes), sago (derived from the pith of the sago palm tree), and fruits such as breadfruit and plantains.[3] Staple foods may also contain, depending on the region, sorghum, olive oil, coconut oil and sugar.[4][5][6]

Demographic profile of staple foods

Of more than 50,000 edible plant species in the world, only a few hundred contribute significantly to human food supplies. Just 15 crop plants provide 90 percent of the world's food energy intake, with rice, maize and wheat comprising two-thirds of human food consumption. These three alone are the staples of over 4 billion people.[7]

Although there are over 10,000 species in the cereal family, just a few have been widely cultivated over the past 2,000 years. Rice alone feeds almost half of humanity. Roots and tubers are important staples for over 1 billion people in the developing world; accounting for roughly 40 percent of the food eaten by half the population of sub-Saharan Africa. Cassava is another major staple food in the developing world, providing a basic diet for around 500 million people. Roots and tubers are high in carbohydrates, calcium and vitamin C, but low in protein.

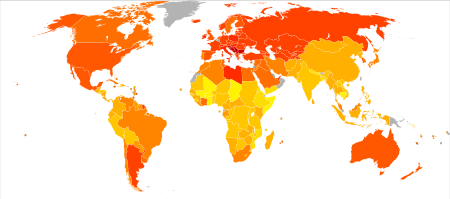

The staple food in different parts of the world is a function of weather patterns, local terrain, farming constraints, acquired tastes and ecosystems. For example, the main energy source staples in the average African diet are cereals (46 percent), roots and tubers (20 percent) and animal products (7 percent). In Western Europe the main staples in the average diet are animal products (33 percent), cereals (26 percent) and roots and tubers (4 percent). Similarly, the energy source staples vary widely within different parts of India, with its colder climate near Himalayas and warmer climate in its south.

Most of the global human population lives on a diet based on one or more of the following staples: rice, wheat, maize (corn), millet, sorghum, roots and tubers (potatoes, cassava, yams and taro), and animal products such as meat, milk, eggs, cheese and fish. Regional staple foods include rye, soybeans, barley, oats, and teff.

With economic development and free trade, many countries have shifted away from low-nutrient density staple foods to higher nutrient density staple foods. Despite this trend, there is growing recognition of the importance of traditional staple crops in nutrition. Efforts are underway to identify better strains with superior nutrition, disease resistance and higher yields.

Some foods such as quinoa - pseudocereal grains that originally came from the Andes - were also staple foods centuries ago.[8] Oca, ulluco and amaranth seed are other foods claimed to be a staple in Andean history.[9] Similarly, pemmican is claimed to be a staple of natives of the Arctic region (for example, the Inuit and Metis). The global consumption of specialty grains such as quinoa, in 2010, was very small compared to other staples such as rice, wheat and maize. These once popular, then forgotten grains are being reevaluated and reintroduced.

| World production 2008 |

Average world yield 2010 |

World's most productive farms 2010[11] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Crop | (metric tons) | (tons per hectare) | (tons per hectare)[12] | Country |

| 1 | Maize (Corn) | 823 million | 5.1 | 28.4 | Israel |

| 2 | Wheat | 690 million | 3.1 | 8.9 | Netherlands, Belgium |

| 3 | Rice | 685 million | 4.3 | 10.8 | Australia |

| 4 | Potatoes | 314 million | 17.2 | 44.3 | USA |

| 5 | Cassava | 233 million | 12.5 | 34.8 | India |

| 6 | Soybeans | 231 million | 2.4 | 3.7 | Turkey |

| 7 | Sweet potatoes | 110 million | 13.5 | 33.3 | Senegal |

| 8 | Sorghum | 66 million | 1.5 | 12.7 | Jordan |

| 9 | Yams | 52 million | 10.5 | 28.3 | Colombia |

| 10 | Plantain | 34 million | 6.3 | 31.1 | El Salvador |

Refining

Rice is most commonly eaten as cooked entire grains, but most other cereals are milled into flour or meal which is used to make bread; noodles or other pasta; and porridges and "mushes" such as polenta or mealie pap. Mashed root vegetables can be used to make similar porridge-like dishes, including poi and fufu. Pulses (particularly chickpeas) and starchy root vegetables, such as Canna, can also be made into flour.

Part of a whole

Although nutritious, staple foods generally do not by themselves provide a full range of nutrients, so other foods need to be added to the diet to ward off malnutrition. For example, the deficiency disease pellagra is associated with a diet consisting primarily of maize, and beriberi with a diet of white (i.e., refined) rice.[13]

Nutritional content

The following table shows the nutrient content of major staple foods in a raw form. Raw grains, however, aren't edible and can not be digested. These must be sprouted, or prepared and cooked for human consumption. In sprouted and cooked form, the relative nutritional and anti-nutritional contents of each of these grains is remarkably different from that of raw form of these grains reported in this table.

| Staple | Maize (corn)[A] | Rice, white[B] | Wheat[C] | Potatoes[D] | Cassava[E] | Soybeans, green[F] | Sweet potatoes[G] | Yams[Y] | Sorghum[H] | Plantain[Z] | RDA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Water content (%) | 10 | 12 | 13 | 79 | 60 | 68 | 77 | 70 | 9 | 65 | |

| Raw grams per 100 g dry weight | 111 | 114 | 115 | 476 | 250 | 313 | 435 | 333 | 110 | 286 | |

| Nutrient | |||||||||||

| Energy (kJ) | 1698 | 1736 | 1574 | 1533 | 1675 | 1922 | 1565 | 1647 | 1559 | 1460 | 8,368–10,460 |

| Protein (g) | 10.4 | 8.1 | 14.5 | 9.5 | 3.5 | 40.6 | 7.0 | 5.0 | 12.4 | 3.7 | 50 |

| Fat (g) | 5.3 | 0.8 | 1.8 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 21.6 | 0.2 | 0.6 | 3.6 | 1.1 | 44–77 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 82 | 91 | 82 | 81 | 95 | 34 | 87 | 93 | 82 | 91 | 130 |

| Fiber (g) | 8.1 | 1.5 | 14.0 | 10.5 | 4.5 | 13.1 | 13.0 | 13.7 | 6.9 | 6.6 | 30 |

| Sugar (g) | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 3.7 | 4.3 | 0.0 | 18.2 | 1.7 | 0.0 | 42.9 | minimal |

| Minerals | [A] | [B] | [C] | [D] | [E] | [F] | [G] | [Y] | [H] | [Z] | RDA |

| Calcium (mg) | 8 | 32 | 33 | 57 | 40 | 616 | 130 | 57 | 31 | 9 | 1,000 |

| Iron (mg) | 3.01 | 0.91 | 3.67 | 3.71 | 0.68 | 11.09 | 2.65 | 1.80 | 4.84 | 1.71 | 8 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 141 | 28 | 145 | 110 | 53 | 203 | 109 | 70 | 0 | 106 | 400 |

| Phosphorus (mg) | 233 | 131 | 331 | 271 | 68 | 606 | 204 | 183 | 315 | 97 | 700 |

| Potassium (mg) | 319 | 131 | 417 | 2005 | 678 | 1938 | 1465 | 2720 | 385 | 1426 | 4700 |

| Sodium (mg) | 39 | 6 | 2 | 29 | 35 | 47 | 239 | 30 | 7 | 11 | 1,500 |

| Zinc (mg) | 2.46 | 1.24 | 3.05 | 1.38 | 0.85 | 3.09 | 1.30 | 0.80 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 11 |

| Copper (mg) | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.25 | 0.41 | 0.65 | 0.60 | - | 0.23 | 0.9 |

| Manganese (mg) | 0.54 | 1.24 | 4.59 | 0.71 | 0.95 | 1.72 | 1.13 | 1.33 | - | - | 2.3 |

| Selenium (μg) | 17.2 | 17.2 | 81.3 | 1.4 | 1.8 | 4.7 | 2.6 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 4.3 | 55 |

| Vitamins | [A] | [B] | [C] | [D] | [E] | [F] | [G] | [Y] | [H] | [Z] | RDA |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 93.8 | 51.5 | 90.6 | 10.4 | 57.0 | 0.0 | 52.6 | 90 |

| Thiamin (B1) (mg) | 0.43 | 0.08 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.23 | 1.38 | 0.35 | 0.37 | 0.26 | 0.14 | 1.2 |

| Riboflavin (B2) (mg) | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.56 | 0.26 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.14 | 1.3 |

| Niacin (B3) (mg) | 4.03 | 1.82 | 6.28 | 5.00 | 2.13 | 5.16 | 2.43 | 1.83 | 3.22 | 1.97 | 16 |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) (mg) | 0.47 | 1.15 | 1.09 | 1.43 | 0.28 | 0.47 | 3.48 | 1.03 | - | 0.74 | 5 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 0.69 | 0.18 | 0.34 | 1.43 | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.91 | 0.97 | - | 0.86 | 1.3 |

| Folate Total (B9) (μg) | 21 | 9 | 44 | 76 | 68 | 516 | 48 | 77 | 0 | 63 | 400 |

| Vitamin A (IU) | 238 | 0 | 10 | 10 | 33 | 563 | 4178 | 460 | 0 | 3220 | 5000 |

| Vitamin E, alpha-tocopherol (mg) | 0.54 | 0.13 | 1.16 | 0.05 | 0.48 | 0.00 | 1.13 | 1.30 | 0.00 | 0.40 | 15 |

| Vitamin K1 (μg) | 0.3 | 0.1 | 2.2 | 9.0 | 4.8 | 0.0 | 7.8 | 8.7 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 120 |

| Beta-carotene (μg) | 108 | 0 | 6 | 5 | 20 | 0 | 36996 | 277 | 0 | 1306 | 10500 |

| Lutein+zeaxanthin (μg) | 1506 | 0 | 253 | 38 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 86 | 6000 |

| Fats | [A] | [B] | [C] | [D] | [E] | [F] | [G] | [Y] | [H] | [Z] | RDA |

| Saturated fatty acids (g) | 0.74 | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 2.47 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.51 | 0.40 | minimal |

| Monounsaturated fatty acids (g) | 1.39 | 0.24 | 0.23 | 0.00 | 0.20 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 1.09 | 0.09 | 22–55 |

| Polyunsaturated fatty acids (g) | 2.40 | 0.20 | 0.72 | 0.19 | 0.13 | 10.00 | 0.04 | 0.27 | 1.51 | 0.20 | 13–19 |

| [A] | [B] | [C] | [D] | [E] | [F] | [G] | [Y] | [H] | [Z] | RDA |

A raw yellow dent corn

B raw unenriched long-grain white rice

C raw hard red winter wheat

D raw potato with flesh and skin

E raw cassava

F raw green soybeans

G raw sweet potato

H raw sorghum

Y raw yam

Z raw plantains

/* unofficial

Note: The highlighted value is the highest nutrient density amongst these staples. Other foods of the world, consumed in smaller quantities, may have nutrient densities higher than these values.

Gallery of food staples

-

Boiled white rice

-

Kidney beans

-

Amaranth (left) and wheat

-

Cassava

-

Sweet potato

-

Edamame - green soybeans

-

Sorghum seeds (left) and popped sorghum

-

Japanese yam

-

Plantains

-

Ulluco

-

Oca

-

Taro

-

Millet

-

Quinoa

See also

References

- ^ United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization: Agriculture and Consumer Protection. "Dimensions of Need - Staple foods: What do people eat?". Retrieved 2010-10-15.

- ^ Staple Foods — Root and Tuber Crops

- ^ Staple Foods II -- Fruits

- ^ African food staples

- ^ About olive oil

- ^ About sugar and sweeteners

- ^ "Dimensions of Need: An atlas of food and agriculture". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 1995.

- ^ E.A. Oelke; et al. "Quinoa". University of Minneasota.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Arbizu and Tapia (1994). "Plant Production and Protection Series No. 26. FAO, Rome, Italy". FAO / Purdue University.

- ^ Allianz. "Food security: Ten Crops that Feed the World". Allianz.

- ^ "FAOSTAT: Production-Crops, 2010 data". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2011.

- ^ The numbers in this column are country average; regional farm productivity within the country varies, with some farms even higher.

- ^ United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization: Agriculture and Consumer Protection. "Rice and Human Nutrition" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-10-15.

- ^ "Nutrient data laboratory". United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved August 10, 2016.