Superabundant number

In mathematics, a superabundant number (sometimes abbreviated as SA) is a certain kind of natural number. Formally, a natural number n is called superabundant precisely when, for all m < n,

where σ denotes the sum-of-divisors function (i.e., the sum of all positive divisors of n, including n itself). The first few superabundant numbers are 1, 2, 4, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, 120, ... (sequence A004394 in the OEIS). Superabundant numbers were defined by Leonidas Alaoglu and Paul Erdős (1944). Unknown to Alaoglu and Erdős, about 30 pages of Ramanujan's 1915 paper "Highly Composite Numbers" were suppressed. Those pages were finally published in The Ramanujan Journal 1 (1997), 119-153. In section 59 of that paper, Ramanujan defines generalized highly composite numbers, which include the superabundant numbers.

Properties

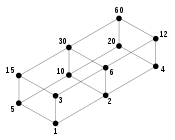

Leonidas Alaoglu and Paul Erdős (1944) proved that if n is superabundant, then there exist an i and a1, a2, ..., ai such that

where pl is the l-th prime number, and

Or to wit, if n is superabundant then the prime decomposition of n has decreasing exponents, the smaller the prime, the larger its exponent.

In fact, ai is equal to 1 except when n is 4 or 36.

Superabundant numbers are closely related to highly composite numbers. It is false that all superabundant numbers are highly composite numbers. In fact, only 449 superabundant and highly composite numbers are the same. For instance, 7560 is highly composite but not superabundant. Alaoglu and Erdős observed that all superabundant numbers are highly abundant. It is false that all superabundant numbers are Harshad numbers. The first exception is the 105th SA number, 149602080797769600. The digit sum is 81, but 81 does not divide evenly into this SA number.

Superabundant numbers are also of interest in connection with the Riemann hypothesis, and with Robin's theorem that the Riemann hypothesis is equivalent to the statement that

for all n greater than the largest known exception, the superabundant number 5040. If this inequality has a larger counterexample, proving the Riemann hypothesis to be false, the smallest such counterexample must be a superabundant number (Akbary & Friggstad 2009).

References

- Akbary, Amir; Friggstad, Zachary (2009), "Superabundant numbers and the Riemann hypothesis", American Mathematical Monthly, 116 (3): 273–275, doi:10.4169/193009709X470128.

- Alaoglu, Leonidas; Erdős, Paul (1944), "On highly composite and similar numbers", Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 56 (3), American Mathematical Society: 448–469, doi:10.2307/1990319, JSTOR 1990319.

External links