Sushruta Samhita

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures and texts |

|---|

|

| Related Hindu texts |

The Sushruta Samhita (सुश्रुतसंहिता, IAST: Suśrutasaṃhitā, literally "Suśruta's Compendium") is an ancient Sanskrit text on medicine and surgery, and one of the most important such treatises on this subject to survive from the ancient world. The Compendium of Suśruta is one of the foundational texts of Ayurveda (Indian traditional medicine), alongside the Caraka-Saṃhitā, the Bheḷa-Saṃhitā, and the medical portions of the Bower Manuscript.[1][2] It is one of the two foundational Hindu texts on medical profession that have survived from ancient India.[3][4]

The Suśrutasaṃhitā is of great historical importance because it includes historically unique chapters describing surgical training, instruments and procedures.[2][5]

History

Ancient qualifications of a Nurse

That person alone is fit to nurse or to attend the bedside of a patient, who is cool-headed and pleasant in his demeanor, does not speak ill of any body, is strong and attentive to the requirements of the sick, and strictly and indefatigably follows the instructions of the physician.

—Sushruta Samhita Book 1, Chapter XXXIV

Translator: Bhishagratna[6]

Date

The early scholar Rudolf Hoernle proposed that given that the author of Satapatha Brahmana – an ancient Vedic text, was aware of Sushruta doctrines, those Sushruta doctrines should be dated based on the composition date of Satapatha Brahmana.[7] The composition date of the Brahmana is itself unclear, added Hoernle, and he estimated it to be about the sixth century BCE.[7] While Loukas et al. date the Sushruta Samhita to the mid 1st-millennium BCE,[8] Boslaugh dates the currently existing text to the 6th-century CE.[9]

Rao in 1985 suggested that the original layer to the Sushruta Samhita was composed in 1st millennium BCE by "elder Sushruta" consisting of five books and 120 chapters, which was redacted and expanded with Uttara-tantra as the last layer of text in 1st millennium CE, bringing the text size to six books and 184 chapters.[10] Walton et al., in 1994, traced the origins of the text to 1st millennium BCE.[11]

Meulenbeld in his 1999 book states that the Suśruta-saṃhitā is likely a work that includes several historical layers, whose composition may have begun in the last centuries BCE and was completed in its presently surviving form by another author who redacted its first five chapters and added the long, final chapter, the "Uttaratantra."[1] It is likely that the Suśruta-saṃhitā was known to the scholar Dṛḍhabala (fl. 300-500 CE, also spelled Dridhabala), which gives the latest date for the version of the work that has survived into the modern era.[1]

Tipton in a 2008 historical perspectives review, states that uncertainty remains on dating the text, how many authors contributed to it and when. Estimates range from 1000 BCE, 800–600 BCE, 600 BCE, 600–200 BCE, 200 BCE, 1–100 CE, and 500 CE.[12] Partial resolution of these uncertainties, states Tipton, has come from comparison of the Sushruta Samhita text with several Vedic hymns particularly the Atharvaveda such as the hymn on the creation of man in its 10th book,[13] the chapters of Atreya Samhita which describe the human skeleton,[14] better dating of ancient texts that mention Sushruta's name, and critical studies on the ancient Bower Manuscript by Hoernle.[12] These information trace the first Sushruta Samhita to likely have been composed by about mid 1st millennium BCE.[12]

Authorship

Suśruta (Devanagari सुश्रुत, an adjective meaning "renowned"[15]) is named in the text as the author, who presented the teaching of his guru, Divodāsa.[16] He is said in ancient texts such as the Buddhist Jatakas to have been a physician who taught in a school in Kashi (Varanasi) in parallel to another medical school in Taxila (on Jhelum river),[17][18] sometime between 1200 BC and 600 BC.[19][20] One of the earliest known mentions of the name Sushruta is in the Bower Manuscript (4th or 5th century), where Sushruta is listed as one of the ten sages residing in the Himalayas.[21]

Rao in 1985 suggested that the author of the original "layer" was "elder Sushruta" (Vrddha Sushruta). The text, states Rao, was redacted centuries later "by another Sushruta, then by Nagarjuna, and thereafter Uttara-tantra was added as a supplement.[10] It is generally accepted by scholars that there were several ancient authors called "Suśruta" who contributed to this text.[22]

Affiliation

The text has been called a Hindu text by many scholars.[9][23][24] The text discusses surgery with the same terminology found in more ancient Hindu texts,[25][26] mentions Hindu gods such as Narayana, Hari, Brahma, Rudra, Indra and others in its chapters,[27][28] refers to the scriptures of Hinduism namely the Vedas,[29][30] and in some cases, recommends exercise, walking and "constant study of the Vedas" as part of the patient's treatment and recovery process.[31] The text also uses terminology of Samkhya and other schools of Hindu philosophy.[32][33][34]

The Sushruta Samhita and Caraka Samhita have religious ideas throughout, states Steven Engler, who then concludes "Vedic elements are too central to be discounted as marginal".[34] These ideas include treating the cow as sacred, extensive use of terms and same metaphors that are pervasive in the Hindu scriptures – the Vedas, and the inclusion of theory of Karma, self (Atman) and Brahman (metaphysical reality) along the lines of those found in ancient Hindu texts.[34] However, adds Engler, the text also includes another layer of ideas, where empirical rational ideas flourish in competition or cooperation with religious ideas.[34]

The text may have Buddhist influences, since a redactor named Nagarjuna has raised many historical questions, whether he was the same person of Mahayana Buddhism fame.[22] Zysk states that the ancient Buddhist medical texts are significantly different from both Sushruta and Caraka Samhita. For example, both Caraka and Sushruta recommend Dhupana (fumigation) in some cases, the use of cauterization with fire and alkali in a class of treatments, and the letting out of blood as the first step in treatment of wounds. Nowhere in the Buddhist Pali texts, states Zysk, are these types of medical procedures mentioned.[35] Similarly, medicinal resins (Laksha) lists vary between Sushruta and the Pali texts, with some sets not mentioned at all.[36] While Sushruta and Caraka are close, many afflictions and their treatments found in these texts are not found in Pali texts.[37]

In general, states Zysk, Buddhist medical texts are closer to Sushruta than to Caraka,[35] and in his study suggests that the Sushruta Samhita probably underwent a "Hinduization process" around the end of 1st millennium BCE and the early centuries of the common era after the Hindu orthodox identity had formed.[38] Clifford states that the influence was probably mutual, with Buddhist medical practice in its ancient tradition prohibited outside of the Buddhist monastic order by a precedent set by Buddha, and Buddhist text praise Buddha instead of Hindu gods in their prelude.[39] The mutual influence between the medical traditions between the various Indian religions, the history of the layers of the Suśruta-saṃhitā remains unclear, a large and difficult research problem.[22]

Suśruta is reverentially held in Hindu tradition to be a descendent of Dhanvantari, the mythical god of medicine,[40] or as one who received the knowledge from a discourse from Dhanvantari in Varanasi.[16]

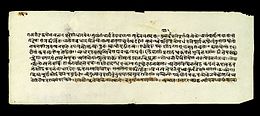

Manuscripts and transmission

Our knowledge of the contents of the Suśruta-saṃhitā is based on editions of the text that were published during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Especially noteworthy is the edition by Vaidya Yādavaśarman Trivikramātmaja Ācārya that also includes the commentary of the scholar Dalhaṇa.[41]

The printed editions are based on just a small subset of manuscripts that were available in the major publishing centres of Bombay, Calcutta and elsewhere when the editions were being prepared, sometimes as few as three or four manuscripts. But these do not adequately represent the large number of manuscript versions of the Suśruta-saṃhitā that have survived into the modern era. These manuscripts exist in the libraries in India and abroad today, perhaps a hundred or more versions of the text exist, and a critical edition of the Suśruta-saṃhitā is yet to be prepared.[42]

Contents

Anatomy and empirical studies

The different parts or members of the body as mentioned before including the skin, cannot be correctly described by one who is not well versed in anatomy. Hence, any one desirous of acquiring a thorough knowledge of anatomy should prepare a dead body and carefully, observe, by dissecting it, and examine its different parts.

—Sushruta Samhita, Book 3, Chapter V

Translators: Loukas et al[8]

The Sushruta Samhita is among the most important ancient medical treatises.[1][43] It is one of the foundational texts of the medical tradition in India, alongside the Caraka-Saṃhitā, the Bheḷa-Saṃhitā, and the medical portions of the Bower Manuscript.[1][2][43]

Scope

The Sushruta Samhita was composed after Charaka Samhita, and except for some topics and their emphasis, both discuss many similar subjects such as General Principles, Pathology, Diagnosis, Anatomy, Sensorial Prognosis, Therapeutics, Pharmaceutics and Toxicology.[44][45][1]

The Sushruta and Charaka texts differ in one major aspect, with Sushruta Samhita providing the foundation of surgery, while Charaka Samhita being primarily a foundation of medicine.[44]

Chapters

The Sushruta Samhita, in its extant form, is divided into 186 chapters and contains descriptions of 1,120 illnesses, 700 medicinal plants, 64 preparations from mineral sources and 57 preparations based on animal sources.[46]

The Suśruta-Saṃhitā is divided into two parts: the first five chapters, which are considered to be the oldest part of the text, and the "Later Section" (Skt. Uttaratantra) that was added by the author Dridhabala. The content of these chapters is diverse, some topics are covered in multiple chapters in different books, and a summary according to the Bhishagratna's translation is as follows:[47][48][49]

| Book | Chapter | Topics (incomplete)[note 1] | Translation Comments | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Prevention versus cure

Sushruta, states Tipton, asserts that a physician should invest effort to prevent diseases as much as curative remedial procedures.[124] An important means for prevention, states Sushruta, is physical exercise and hygienic practices.[124] The text adds that excessive strenuous exercise can be injurious and make one more susceptible to diseases, cautioning against such excess.[12] Regular moderate exercise, suggests Sushruta, improves resistance to disease and physical decay.[124] Shushruta has written Shlokas on prevention of diseases.

Human skeleton

The Sushruta Samhita states, per Hoernle translation, that "the professors of Ayurveda speak of three hundred and sixty bones, but books on Salya-Shastra (surgical science) know of only three hundred".[125] The text then lists the total of 300 as follows: 120 in the extremities (e.g. hands, legs), 117 in pelvic area, sides, back, abdomen and breast, and 63 in neck and upwards.[125] The text then explains how these subtotals were empirically verified.[126] The discussion shows that the Indian tradition nurtured diversity of thought, with Sushruta school reaching its own conclusions and differing from the Atreya-Caraka tradition.[126]

The osteological system of Sushruta, states Hoernle, follows the principle of homology, where the body and organs are viewed as self-mirroring and corresponding across various axes of symmetry.[127] The differences in the count of bones in the two schools is partly because Charaka Samhita includes thirty two teeth sockets in its count, and their difference of opinions on how and when to count a cartilage as bone (both count cartilages as bones, unlike current medical practice).[128][129]

Surgery

Training future surgeons

Students are to practice surgical techniques on gourds and dead animals.

—Sushruta Samhita, Book 1, Chapter IX

Translator: Engler[34]

The Sushruta Samhita is best known for its approach and discussions of surgery.[44] It was one of the first in human history to suggest that a student of surgery should learn about human body and its organs by dissecting a dead body.[44] A student should practice, states the text, on objects resembling the diseased or body part.[130] Incision studies, for example, are recommended on Pushpaphala (squash, Cucurbita maxima), Alavu (bottle gourd, Lagenaria vulgaris), Trapusha (cucumber, Cucumis pubescens), leather bags filled with fluids and bladders of dead animals.[130]

The ancient text, state Menon and Haberman, describes haemorrhoidectomy, amputations, plastic, rhinoplastic, ophthalmic, lithotomic and obstetrical procedures.[44]

The Sushruta mentions various methods including sliding graft, rotation graft and pedicle graft.[131] Reconstruction of a nose (rhinoplasty) which has been cut off, using a flap of skin from the cheek is also described.[132] Labioplasty too has received attention in the samahita.[133]

Medicinal herbs

The Sushruta Samhita, along with the Sanskrit medicine-related classics Atharvaveda and Charak Samhita, together describe more than 700 medicinal herbs.[134] The description, states Padma, includes their taste, appearance and digestive effects to safety, efficacy, dosage and benefits.[134]

Reception

A number of Sushruta's contributions have been discussed in modern literature. Some of these include Hritshoola (heart pain), circulation of vital body fluids (such as blood (rakta dhatu) and lymph (rasa dhatu), Madhumeha, obesity, and hypertension.[46] Kearns & Nash (2008) state that the first mention of leprosy is described in Sushruta Samhita.[135][136] The text discusses kidney stones and its surgical removal.[137]

Transmission outside India

The text was translated to Arabic as Kitab Shah Shun al-Hindi' in Arabic, also known as Kitab i-Susurud, in Baghdad during the early 8th century at the instructions of a member of the Barmakid family of Baghdad.[138][10] Yahya ibn Barmak facilitated a major effort at collecting and translating Sanskrit texts such as Vagbhata's Astangahrdaya Samhita, Ravigupta's Siddhasara and Sushruta Samhita.[139] The Arabic translation reached Europe by the end of the medieval period.[140][141] There is some evidence that in Renaissance Italy, the Branca family of Sicily[140] and Gasparo Tagliacozzi (Bologna) were familiar with the rhinoplastic techniques mentioned in the Sushruta Samhita.[142][143][141]

The text was known to the Khmer king Yaśovarman I (fl. 889-900) of Cambodia. Suśruta was also known as a medical authority in Tibetan literature.[138]

In India, a major commentary on the text, known as Nibandha-samgraha, was written by Dalhana in ca. 1200 CE.

Modern translations

The editio princeps of the text was prepared by Madhusudan Datta (Calcutta 1835). A partial English translation by U. C. Datta appeared in 1883. English translations of the full text were published by A. M. Kunte (Bombay 1876).[10] The first English translation of the Sushruta Samhita was by Kaviraj Kunjalal Bhishagratna, who published it in three volumes between 1907 and 1916 (reprinted 1963, 2006).[144][note 1]

An English translation of both the Sushruta Samhita and Dalhana's commentary was published in three volumes by P. V. Sharma in 1999.[145]

See also

Notes

References

- ^ a b c d e f Meulenbeld 1999, pp. 203–389 (Volume IA).

- ^ a b c Rây 1980.

- ^ E. Schultheisz (1981), History of Physiology, Pergamon Press, ISBN 978-0080273426, page 60-61, Quote: "(...) the Charaka Samhita and the Susruta Samhita, both being recensions of two ancient traditions of the Hindu medicine".

- ^ Wendy Doniger (2014), On Hinduism, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199360079, page 79;

Sarah Boslaugh (2007), Encyclopedia of Epidemiology, Volume 1, SAGE Publications, ISBN 978-1412928168, page 547, Quote: "The Hindu text known as Sushruta Samhita is possibly the earliest effort to classify diseases and injuries" - ^ Valiathan 2007.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, p. 307.

- ^ a b Hoernle 1907, p. 8.

- ^ a b Loukas 2010, pp. 646–650.

- ^ a b Boslaugh 2007, p. 547, Quote: "The Hindu text known as Sushruta Samhita (600 AD) is possibly the earliest effort to classify diseases and injuries"..

- ^ a b c d Ramachandra S.K. Rao, Encyclopaedia of Indian Medicine: historical perspective, Volume 1, 2005 Reprint (Original: 1985), pp 94-98, Popular Prakashan

- ^ Walton 1994, p. 586.

- ^ a b c d Tipton 2008, pp. 1553–1556.

- ^ Hoernle 1907, pp. 109–111.

- ^ Banerjee 2011, pp. 320–323.

- ^ Monier-Williams, A Sanskrit Dictionary (1899).

- ^ a b Bhishagratna, Kunjalal (1907). An English Translation of the Sushruta Samhita, based on Original Sanskrit Text. Calcutta. p. 1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Hoernle 1907, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Amaresh Datta, various. The Encyclopaedia Of Indian Literature (Volume One (A To Devo)). Sahitya academy. p. 311.

- ^ David O. Kennedy. Plants and the Human Brain. Oxford. p. 265.

- ^ Singh, P.B.; Pravin S. Rana (2002). Banaras Region: A Spiritual and Cultural Guide. Varanasi: Indica Books. p. 31. ISBN 81-86569-24-3.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Kutumbian 2005, pp. XXXII–XXXIII.

- ^ a b c Meulenbeld 1999, pp. 347–350 (Volume IA).

- ^ Schultheisz 1981, pp. 60–61, Quote: "(...) the Charaka Samhita and the Susruta Samhita, both being recensions of two ancient traditions of the Hindu medicine.".

- ^ Loukas 2010, p. 646, Quote: Susruta's Samhita emphasized surgical matters, including the use of specific instruments and types of operations. It is in his work that one finds significant anatomical considerations of the ancient Hindu.".

- ^ Hoernle 1907, pp. 8, 109–111.

- ^ Raveenthiran, Venkatachalam (2011). "Knowledge of ancient Hindu surgeons on Hirschsprung disease: evidence from Sushruta Samhita of circa 1200-600 bc". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 46 (11). Elsevier BV: 2204–2208. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.07.007.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, p. 156 etc.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 6–7, 395 etc.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 157, 527, 531, 536 etc.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 181, 304–305, 366, lxiv-lxv etc.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, p. 377 etc.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 113-121 etc.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1916, pp. 285, 381, 407, 409, 415 etc.

- ^ a b c d e Engler 2003, pp. 416–463.

- ^ a b Zysk 2000, p. 100.

- ^ Zysk 2000, p. 81, 83.

- ^ Zysk 2000, pp. 74–76, 115–116, 123.

- ^ Zysk 2000, p. 4-6, 25-26.

- ^ Terry Clifford (2003), Tibetan Buddhist Medicine and Psychiatry: The Diamond Healing, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120817845, pages 35-39

- ^ Monier-Williams, A Sanskrit Dictionary, s.v. "suśruta"

- ^ Ācārya, Yādavaśarman Trivikrama (1938). Suśrutasaṃhitā, Suśrutena viracitā, Vaidyavaraśrīḍalhaṇācāryaviracitayā Nibandhasaṃgrahākhyavyākhyayā samullasitā, Ācāryopāhvena Trivikramātmajena Yādavaśarmaṇā saṃśodhitā. Mumbayyāṃ: Nirnaya Sagara Press.

- ^ Wujastyk, Dominik (2013). "New Manuscript Evidence for the Textual and Cultural History of Early Classical Indian Medicine". In Wujastyk, Dominik; Cerulli, Anthony; Preisendanz, Karin (eds.). Medical Texts and Manuscripts in Indian Cultural History. New Delhi: Manohar. pp. 141–57.

- ^ a b Wujastyk, Dominik (2003). The Roots of Ayurveda. London etc.: Penguin. pp. 149–160. ISBN 0140448241.

- ^ a b c d e Menon IA, Haberman HF (1969). "Dermatological writings of ancient India". Med Hist. 13 (4): 387–392. doi:10.1017/s0025727300014824. PMC 1033984. PMID 4899819.

- ^ Ray, Priyadaranjan; Gupta, Hirendra Nath; Roy, Mira (1980). Suśruta Saṃhita (a Scientific Synopsis). New Delhi: INSA.

- ^ a b Dwivedi & Dwivedi (2007)

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1916.

- ^ Martha Ann Selby (2005), Asian Medicine and Globalization (Editor: Joseph S. Alter), University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 978-0812238662, page 124

- ^ RP Das (1991), Medical Literature from India, Sri Lanka, and Tibet (Editors: Gerrit Jan Meulenbeld, I. Julia Leslie), BRILL Academic, ISBN 978-9004095229, pages 25-26

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 1–15.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 16–20.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 21–32.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 33–35.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 36–44.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 45–55.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 56–63.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 64–70.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 71–73.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 74–77.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 78–87.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 88–97.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 98–105.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 106–119.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 120–140.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 141–154.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 155–161.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 162–175.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 176–182.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 183–193.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 194–211.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 212–219.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 220–227.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 228–237.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 238–246.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 247–255.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 256–265.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 266–269.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 270–283.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 284–287.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 288–571.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 1–17.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 18–24.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 25–30.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 31–34.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 35–42.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 43–49.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 50–54.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 55–60.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 61–66.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 67–71.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 72–78.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 79–84.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 85–93.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 94–96.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 97–100.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 101–111.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 113–121.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 122–133.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 134–143.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 144–158.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 158–172.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 173–190.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 191–197.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 198–208.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 209–215.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 216–238.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 259–264.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 265–477.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 478–671.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1911, pp. 673–684.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, pp. 685–736.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1916, pp. 1–105.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1916, pp. 106–117.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1916, pp. 117–123.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1916, pp. 131–140.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1916, pp. 141–163.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1916, pp. 169–337.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1916, pp. 338–372.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1916, pp. 387–391.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1916, pp. 396–405.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1916, pp. 406–416.

- ^ a b c Tipton 2008, p. 1554.

- ^ a b Hoernle 1907, p. 70.

- ^ a b Hoernle 1907, pp. 70–72.

- ^ Hoernle 1907, p. 72.

- ^ Hoernle 1907, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Bhishagratna 1907, p. xxiv-xxv.

- ^ a b Bhishagratna 1907, p. xxi.

- ^ Lana Thompson. Plastic Surgery. ABC-CLIO. p. 8.

- ^ Melvin A. Shiffman, Alberto Di Gi. Advanced Aesthetic Rhinoplasty: Art, Science, and New Clinical Techniques. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 132.

- ^ Sharma, Kumar. History BA (Programme) Semester II: Questions and Answers , University of Delhi. Pearson Education India. p. 147.

- ^ a b "Ayurveda". Nature. 436: 486. doi:10.1038/436486a.

- ^ Kearns & Nash (2008)

- ^ Aufderheide, A. C.; Rodriguez-Martin, C. & Langsjoen, O. (page 148)

- ^ Lock etc., page 836

- ^ a b Meulenbeld 1999, p. 352 (Volume IA).

- ^ Charles Burnett (2015), The Cambridge World History, Volume 5, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0521190749, page 346

- ^ a b Scuderi, Nicolò; Toth, Bryant A. (2016). International Textbook of Aesthetic Surgery. Springer. ISBN 9783662465998.

- ^ a b Menick, Frederick J (11 October 2017). "Paramedian Forehead Flap Nasal Reconstruction: History of the Procedure, Problem, Presentation". Retrieved 30 July 2018.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Lock etc., page 607

- ^ New Scientist Jul 26, 1984, p. 43

- ^ Kenneth Zysk (2010), Medicine in the Veda: Religious Healing in the Veda, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814004, page 272 with footnote 36

- ^ Sharma, Priya Vrata (2001). Suśruta-Saṃhitā, with English Translation of Text and Ḍalhaṇa's Commentary Along with Critical Notes. Haridas Ayurveda Series 9. Vol. 3 vols. Varanasi: Chowkhambha Visvabharati. OCLC 42717448.

Bibliography

- Boslaugh, Sarah (2007). Encyclopedia of Epidemiology. Vol. 1. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1412928168.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Balodhi, J. P. (1987). "Constituting the outlines of a philosophy of Ayurveda: mainly on mental health import". Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 29 (2): 127–31. PMC 3172459. PMID 21927226.

- Banerjee, Anirban D.; et al. (2011). "Susruta and Ancient Indian Neurosurgery". World Neurosurgery. 75 (2). Elsevier: 320–323. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2010.09.007.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bhishagratna, Kaviraj KL (1907). An English Translation of the Sushruta Samhita in Three Volumes, (Volume 1, Archived by University of Toronto)' (PDF). Archived from the original on 1967-03-13.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bhishagratna, Kaviraj KL (1911). An English Translation of the Sushruta Samhita in Three Volumes, (Volume 2, Archived by University of Toronto)' (PDF). Archived from the original on 2001-05-30.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bhishagratna, Kaviraj KL (1916). An English Translation of the Sushruta Samhita in Three Volumes, (Volume 3, Archived by University of Toronto)' (PDF). Archived from the original on 2001-05-30.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dwivedi, Girish; Dwivedi, Shridhar (2007). "History of Medicine: Sushruta – the Clinician – Teacher par Excellence" (PDF). Indian Journal of Chest Diseases and Allied Sciences. 49 (4).

- Engler, Steven (2003). "" Science" vs." Religion" in Classical Ayurveda". Numen. 50 (4): 416–463. doi:10.1163/156852703322446679.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hoernle, A. F. Rudolf (1907). Studies in the Medicine of Ancient India: Osteology or the Bones of the Human Body. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kutumbian, P. (2005). Ancient Indian Medicine. Orient Longman. ISBN 978-812501521-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Loukas, M; et al. (2010). "Anatomy in ancient India: A focus on the Susruta Samhita". Journal of Anatomy. 217 (6): 646–650. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01294.x. PMC 3039177. PMID 20887391.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rana, R. E.; Arora, B. S. (2002). "History of plastic surgery in India". Journal of Postgraduate Medicine. 48 (1).

- Rây, Priyadaranjan; et al. (1980). Suśruta saṃhitā: a scientific synopsis. Indian National Science Academy. OCLC 7952879.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Meulenbeld, Gerrit Jan (1999). A History of Indian Medical Literature. Groningen: Brill (all volumes, 1999-2002). ISBN 978-9069801247.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sharma, P. V. (1992). History of medicine in India, from antiquity to 1000 A.D. New Delhi: Indian National Science Academy. OCLC 26881970.

- Schultheisz, E. (1981). History of Physiology. Pergamon Press. ISBN 978-0080273426.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Raveenthiran, Venkatachalam (2011). "Knowledge of ancient Hindu surgeons on Hirschsprung disease: evidence from Sushruta Samhita of circa 1200-600 bc". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 46 (11). Elsevier BV: 2204–2208. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.07.007.

- Tipton, Charles (2008). "Susruta of India, an unrecognized contributor to the history of exercise physiology". Journal of Applied Physiology. 104 (6): 1553–1556. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00925.2007. PMID 18356481.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Valiathan, M. S (2007). The legacy of Suśruta. Orient Longman. ISBN 9788125031505. OCLC 137222991.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Walton, John (1994). The Oxford medical companion. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-262355-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zysk, Kenneth (2000). Asceticism and Healing in Ancient India: Medicine in the Buddhist Monastery. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-8120815285.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - D. P. Agrawal. Sushruta: The Great Surgeon of Yore.

- Chari PS. 'Sushruta and our heritage', Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery.

External links

- Sushruta Samhita Volume 1, in English

- Sushruta Samhita Volume 2, in English

- Sushruta Samhita Volume 3, in English

- Sutrasthana, Nidanasthana, Sharirasthana, Cikitsasthana, Kalpasthana, Uttaratantra: English translation, proofread, correct spelling, interwoven glossary

- Sushruta Samhita (English Translation)

- Syncretism in the Caraka and Suśruta saṃhitās