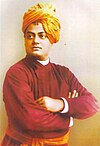

Swami Vivekananda and meditation

Meditation played a very important role in the life and teachings of Vivekananda. He was interested in meditation from his childhood. His master Ramakrishna found him a dhyana-siddha (expert in meditation). In December 1892, Vivekananda went to Kanyakumari and meditated for three days on a large rock and took the resolution to dedicate his life to serve humanity. The event is known as the Kanyakumari resolve of 1892. He reportedly also meditated for a long time on the day of his death (4 July 1902).

Vivekananda is considered as the introducer of meditation to the Western countries. In his book Raja Yoga and lectures, he widely discussed meditation, its purpose and procedure. He described "meditation" as a bridge that connects human soul to the God. He defined "meditation" as a state "when the mind has been trained to remain fixed on a certain internal or external location, there comes to it the power of flowing in an unbroken current, as it were, towards that point."[1]

Meditation in Vivekananda's life

Meditation, which gives an insight to the depth and breadth of the mystical traditions of India, was developed by Ancient Hindu Seers. He propagated it to the world through his lectures and practical lessons. He stressed the need to concentrate on the mind which is a lamp that gives insight to every part of our soul.[1]

Vivekananda defined meditation, first as a process of self-appraisal of all thoughts to the mind. He then defined the next step as to “assert what we really are — existence, knowledge and bliss — being, knowing, and loving,” which would result in “unification of the subject and object.”[2]

Vivekananda’s meditation is practiced under the two themes of “Meditation according to Yoga” which is considered a practical and mystical approach, and of “Meditation according to Vedanta” which means a philosophical and transcendental approach. Both themes have the same end objective of realizing illumination through realization of the “Supreme”. [3]

Childhood

Vivekananda was born Narendranath Datta on 12 January 1863 in Calcutta (now Kolkata). From his very childhood, he was deeply interested in meditation and used to meditate before the images of deities such as Shiva, Rama, and Sita.[4] He was able to practice deep meditation at the age of eight.[5]

In his childhood, when Narendra was playing meditation with his friend, suddenly a cobra appeared. Narendra's friends got frightened and fled, But, Narendra was so much absorbed in meditation that he did not even notice the cobra or hear his friends' calls.[3]

Youth (1881—1886)

When Vivekananda (then Narendratah Datta) met Ramakrishna in 1881, the latter found Vivekananda dhyana–siddha (expert in meditation).[6] Between 1881 and 1886, as an apprentice of Ramakrishna, he took meditation lessons from him, which made his expertise on meditation more firm.[7] Narendra wanted to experience Nirvikalpa Samadhi (the highest stage of meditation) and so requested Ramakrishna to help him to attain that state. But Ramakrishna wanted to young Narendra to devote to the service of mankind, and told him that desiring to remain absorbed in Samadhi was a small-minded desire.[8][9] He also assured him that one could go to "a state higher even than that" by serving mankind, because everything is God's own manifestation. This dictum of Ramakrishna deeply influenced Narendranath.[8]

Experience of Nirvikalpa Samadhi in Cossipore Garden House

Narendranath first experienced Nirvikalpa Samadhi at Cossipore Garden House in Calcutta. One evening when he was meditating with his friend Gopal (senior), he suddenly felt a light behind his head. As he concentrated on the light, it became more luminous. Narendra concentrated further on the light and found it getting subsumed in to "the Absolute". He became unconscious. When he regained consciousness after sometime, his first question was "Gopal–da, where is my body?" Gopal felt worried and informed this event to Ramakrishna.[10]

Meditation at Baranagar Math

After the death of Ramakrishna in August 1886, Narendra and few other monastic disciples of Ramakrishna converted a dilapidated house at Baranagar into a new math (monastery). There they practiced religious austerities and meditation. Narendra later reminisced about his days at the Baranagar math:[11]

We underwent a lot of religious practice at the Baranagar Math. We used to get up at 3:00 am and become absorbed in japa and meditation. What a strong spirit of detachment we had in those days! We had no thought even as to whether the world existed or not.

Meditation during the Wandering years

Between 1888 and 1893, Narendranath travelled all over India as a Parivrajaka Sadhu, a wandering monk, and visited many states and holy sites. During his tours he always wanted to live in secluded locations where he could stay alone and concentrate on meditation. During these lonely years, he reportedly gained inspiration from the words of Gautama Buddha—[12][13]

Go forward without a path,

Fearing nothing, caring for nothing!

Wandering alone, like the rhinoceros!

Even as a lion, not trembling at noises,

Even as the wind, not caught in the net,

Even as the lotus leaf, untainted by water,

Do thou wander alone, like the rhinoceros!

Once when Narendra was meditating under a pepul tree in the Himalayas, he realized the oneness of man and all other objects in the universe and that man was just a miniature of the whole universe, i.e., the human life follows the same rules as applicable for the whole universe. He wrote about this experience to his brother-disciple Swami Ashokananada.[13]

Kanyakumari resolve of 1892

Vivekananda reached Kanyakumari on 24 December 1892 and meditated for three days at a stretch, from 25 December to 27 December, on a large mid-sea rock, on aspects of India's past, present and future. There he reportedly had a "vision of one India" and took the resolve to dedicate his life for the service of humanity. This resolve of 1892 is known as "Kanyakumari resolve of 1892".[14][15]

Meditation in the West

In 1893 Vivekananda travelled to the West and participated in the Parliament of the World's Religions, which was held in Chicago in that year. Between 1893 and 1897, he conducted hundreds of public and private lectures and classes in the United States and England. Even during these active days he continued meditating on a regular basis, and his hectic work schedule could not disturb his meditations.[16]

Experience of Nirvikalpa Samadhi in England (December 1896)

In 1895 Vivekananda went to England and started conducting lectures and private classes. In December 1896, during when he was teaching meditation to his disciples, he himself went into an absorbed deep samadhi. His meditating posture was captured by a disciple. [17]

Meditation on 4 July 1902

Vivekananda died a few minutes after 9 pm on 4 July 1902. Even on that day he practiced meditation for many hours. He also sang a devotional song on Hindu goddess Kali. This was his last meditation.[18][19]

Vivekananda's teachings on meditation

Vivekananda is considered as the introducer of meditation to the Western countries.[20] He realized "concentration is the essence of all knowledge" and meditation plays an important role in strengthening one's concentration.[21] He said "man-making" was his mission, and he felt for that we needed a composite culture of knowledge, work, love and meditated mind.[22] He stressed on practicing meditation on regular basis.[23] Vivekananda told, meditation not only improves one's concentration, but also improves his behavioural control.[24]

Definition of Dhyana (meditation)

To Vivekananda, meditation (Dhyana) was a bridge that connected human soul to the God, the Supreme.[25] He defined Dhyana meditation as—[26]

When the mind has been trained to remain fixed on a certain internal or external location, there comes to it the power of flowing in an unbroken current, as it were, towards that point. This state is called Dhyana. When one has so intensified the power of Dhyana as to be able to reject the external part of perception and remain meditating only on the internal part, the meaning, that state is called Samadhi.

Procedure of meditation suggested by Vivekananda

In the book Raja Yoga and several other lectures, Vivekananda also suggested the procedure of meditation. He said—[27]

First, to sit in the posture In which you can sit still for a long time. All the nerve currents which are working pass along the spine. The spine is not intended to support the weight of the body. Therefore the posture must be such that the weight of the body is not on the spine. Let it be free from all pressure.

Vivekananda published a summary of Raja Yoga from Kurma Purana. In the summary, he defined the meaning, purpose and procedure of meditation. He wrote one of the procedures of meditation—[28]

Sit straight, and look at the tip of your nose. Later on we shall come to know how that concentrates the mind, how by controlling the two optic nerves one advances a long way towards the control of the arc of reaction, and so to the control of the will. Here are a few specimens of meditation. Imagine a lotus upon the top of the head, several inches up, with virtue as its centre, and knowledge as its stalk. The eight petals of the lotus are the eight powers of the Yogi. Inside, the stamens and pistils are renunciation. If the Yogi refuses the external powers he will come to salvation. So the eight petals of the lotus are the eight powers, but the internal stamens and pistils are extreme renunciation, the renunciation of all these powers. Inside of that lotus think of the Golden One, the Almighty, the Intangible, He whose name is Om, the Inexpressible, surrounded with effulgent light. Meditate on that. Another meditation is given. Think of a space in your heart, and in the midst of that space think that a flame is burning. Think of that flame as your own soul and inside the flame is another effulgent light, and that is the Soul of your soul, God. Meditate upon that in the heart. Chastity, non-injury, forgiving even the greatest enemy, truth, faith in the Lord, these are all different Vrittis. Be not afraid if you are not perfect in all of these; work, they will come. He who has given up all attachment, all fear, and all anger, he whose whole soul has gone unto the Lord, he who has taken refuge in the Lord, whose heart has become purified, with whatsoever desire he comes to the Lord, He will grant that to him. Therefore worship Him through knowledge, love, or renunciation.

References

Citations

- ^ a b "Meditation and Its Methods: by Swami Vivekananda; edited with a biographical sketch by Swami Chetanananda". Vedanta Society of St. Louis. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- ^ "Meditation:From notes on Jnana Yoga". Vivekananda.net. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- ^ a b Vivekananda 1976, p. 18.

- ^ Ghosh 2003, p. 22.

- ^ Dubey, p. 38.

- ^ Sandarshanananda 2013, p. 655.

- ^ Sandarshanananda 2013, p. 656.

- ^ a b Sandarshanananda 2013, p. 657.

- ^ Bhuyan 2003, p. 7.

- ^ Vivekananda 1976, p. 20.

- ^ Chetananda 1997, p. 38.

- ^ Cooper 1984, p. 49.

- ^ a b Vivekananda 1976, p. 22.

- ^ Agarwal 1998, p. 59.

- ^ Banhatti 1995, p. 24.

- ^ Vivekananda 1976, p. 23.

- ^ Mookherjee 2002, p. 157.

- ^ Paranjape 2004, p. 37.

- ^ Banhatti 1995, p. 46.

- ^ MacLean & 2013 673.

- ^ MacLean 2013, p. 671.

- ^ Sandarshanananda, p. 668.

- ^ Sandarshanananda, p. 661.

- ^ MacLean, p. 672.

- ^ Sandarshanananda, p. 660.

- ^ Wikisource:The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda/Volume 1/Raja-Yoga/Dhyana And Samadhi

- ^ Wikisource:The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda/Volume 1/Lectures And Discourses/Practical Religion: Breathing And Meditation

- ^ Wikisource:The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda/Volume 1/Raja-Yoga/Raja-Yoga In Brief

Bibliography

- Agarwal, Satya P. (1 January 1995). The Social Message of the Gita: Symbolized as Lokasaṁgraha : Self-composed Sanskrit Ślokas with English Commentary. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 978-81-208-1319-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Banhatti, Gopal Shrinivas (1995). Life And Philosophy Of Swami Vivekananda. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-7156-291-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Chauhan, Abnish Singh (2004), Swami Vivekananda: Select Speeches, Prakash Book Depot, ISBN 978-8179774663

- Chauhan, Abnish Singh (2006), Speeches of Swami Vivekananda and Subhash Chandra Bose: A Comparative Study, Prakash Book Depot, ISBN 9788179771495

- Cooper, Carebanu (1984). Swami Vivekananda: Literary Biography. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bhuyan, P. R. (2003). Swami Vivekananda: Messiah of Resurgent India. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 978-81-269-0234-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Agarwal, Satya P. (1998), The social role of the Gītā: how and why, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1524-7

- Chetananda, Swami (1997). God lived with them: life stories of sixteen monastic disciples of Sri Ramakrishna. St. Louis, Missouri: Vedanta Society of St. Louis. ISBN 0-916356-80-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dubey, Scharada. The Best Days Of My Life. Scholastic India Pvt Limited. ISBN 978-81-8477-014-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ghosh, Gautam (2003). The Prophet of Modern India: A Biography of Swami Vivekananda. Rupa & Company. ISBN 978-81-291-0149-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mookherjee, Braja Dulal (2002). The Essence of Bhagavad Gita. Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-81-87504-40-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - MacLean, Katherine (2013). "The Importance of Meditation". Swami Vivekananda: New Perspectives An Anthology on Swami Vivekananda. Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture. ISBN 978-93-81325-23-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Paranjape, Makarand (13 December 2004). Penguin Swami Vivekananda Reader. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-81-8475-890-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sandarshanananda, Swami (2013). "Meditation: Its Influence on the Mind of the Future". Swami Vivekananda: New Perspectives An Anthology on Swami Vivekananda. Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture. ISBN 978-93-81325-23-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vivekananda, Swami (1976). Meditation and Its Methods According to Swami Vivekananda. Vedanta Press. ISBN 978-0-87481-030-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)