Thomas H. Ince

Thomas H. Ince | |

|---|---|

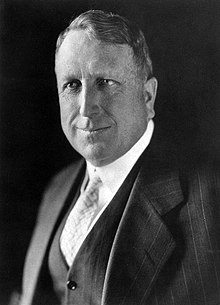

Ince, c. 1918 | |

| Born | Thomas Harper Ince November 16, 1880 |

| Died | November 19, 1924 (aged 44) |

| Other names | Creator of the Hollywood Studio system Father of the Western |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1897–1924 |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3 |

| Relatives | John Ince (brother) Ralph Ince (brother) Willette Kershaw (sister-in-law) |

Thomas Harper Ince (November 16, 1880 – November 19, 1924) was an American silent era filmmaker and media proprietor.[1] Ince was known as the "Father of the Western" and was responsible for making over 800 films.[2]

Ince revolutionized the motion picture industry by creating the first major Hollywood studio facility and invented movie production by introducing the "assembly line" system of filmmaking. He was the first mogul to build his own film studio dubbed "Inceville" in Palisades Highlands. Ince was also instrumental in developing the role of the producer in motion pictures. Three of his films, The Italian (1915), for which he wrote the screenplay, Hell's Hinges (1916) and Civilization (1916), which he directed, were selected for preservation by the National Film Registry. He later entered into a partnership with D. W. Griffith and Mack Sennett to form the Triangle Motion Picture Company, whose studios are the present-day site of Sony Pictures. He then built a new studio about a mile from Triangle, which is now the site of Culver Studios.[3][4]

Ince's untimely death at the height of his career, after he became severely ill aboard the private yacht of media tycoon William Randolph Hearst, has caused much speculation, although the official cause of his death was heart failure.[5]

Life and career

[edit]

Thomas Harper Ince was born on November 16, 1880, in Newport, Rhode Island, the middle of three sons and a daughter raised by English immigrants, John E. and Emma Ince.[6] His father was born in Wigan, Lancashire in 1841, and was the youngest of nine boys who enlisted in the British Navy as a "powder monkey". He later disembarked at San Francisco, and found work as a reporter and coal miner. Around 1887, when Ince was about seven, the family moved to Manhattan to pursue theater work. Ince's father worked as both an actor and musical agent and his mother, Ince himself, sister Bertha and brothers, John and Ralph all worked as actors. Ince made his Broadway debut at 15 in a small role of a revival 1893 play, Shore Acres by James A. Herne.[7] He appeared with several stock companies as a child and was later an office boy for theatrical manager Daniel Frohman.[8][9] He later formed an unsuccessful vaudeville company known as "Thomas H. Ince and His Comedians" in Atlantic Highlands, New Jersey. In 1907, Ince met actress Elinor Kershaw ("Nell") and they were married on October 19 of that year. They had three children.

Ince's directing career began in 1910 through a chance encounter in New York City with an employee from his old acting troupe, William S. Hart. Ince found his first film work as an actor for the Biograph Company, directed by his future partner, D.W. Griffith. Griffith was impressed enough with Ince to hire him as a production coordinator at Biograph. This led to more work coordinating productions at Carl Laemmle's Independent Motion Pictures Co. (IMP).[8] That same year, a director at IMP was unable to complete work on a small feature film, so in a moment of bravado, Ince suggested that Laemmle hire him as a full-time director to complete the film. Impressed with the young man, Laemmle sent him to Cuba to make one-reel shorts with his new stars, Mary Pickford and Owen Moore, out of the reach of Thomas Edison's Motion Picture Patents Company-—the trust that was attempting to crush all independent production companies and corner the market on film production.[10] Ince's output, however, was small. Although he tackled many different subjects, he was strongly drawn to westerns and American Civil War dramas.

Clashes between the trust and independent films became exacerbated, so Ince moved to California to escape these pressures. He hoped to achieve the effects accomplished with minimal facilities like Griffith, which he believed, could only be accomplished in Hollywood. After only a year with IMP, Ince quit. In September 1911, Ince walked into the offices of actor-financier Charles O. Baumann (1874–1931) who co-owned the New York Motion Picture Company (NYMP) with actor-writer Adam Kessel, Jr. (1866–1946). Ince had found out that NYMPC had recently established a West Coast studio named Bison Studios at 1719 Alessandro (now known as Glendale Blvd.) in Edendale (present-day Echo Park) to make westerns and he wanted to direct those pictures.[11][12]

The offer came as a distinct shock, but I kept cool and concealed my excitement. I tried to convey the impression that he would have to raise the ante a trifle if he wanted me. That also worked, and I signed a contract for three months at $150 a week. Very soon after that, with Mrs. Ince, my cameraman, property man and Ethel Grandin, my leading woman, I turned my face westward.[8]

Together with his young wife and a small entourage, Ince moved to Bison Studios to begin work immediately. He was shocked, however, to discover that the studio was nothing more than a "tract of land graced only by a four-room bungalow and a barn."

Inceville

[edit]Ince's aspirations soon led him to leave the narrow confines of Edendale and find a location that would give him greater scope and variety. He settled upon a 460-acre (1.9 km2) tract of land called Bison Ranch located at Sunset Blvd. and Pacific Coast Highway in the Santa Monica Mountains, (the present-day location of the Self-Realization Fellowship Lake Shrine) which he rented by the day.[12] By 1912, he had earned enough money to purchase the ranch and was granted permission by NYMP to lease another 18,000 acres (73 km2) in the Palisades Highlands stretching 7.5 miles (12.1 km) up Santa Ynez Canyon between Santa Monica and Malibu where Universal Studios was eventually established, which was owned by The Miller Bros of Ponca City, Oklahoma. And it was here Ince built his first movie studio.[11][13]

The "Miller 101 Bison Ranch Studio", which the Millers dubbed "Inceville" (and was later re-christened "Triangle Ranch") was the first of its kind in that it featured silent stages, production offices, printing labs, a commissary large enough to serve lunch to hundreds of workers, dressing rooms, props houses, elaborate sets, and other necessities – all in one location. While the site was under construction, Ince also leased the 101 Ranch and Wild West Show from the Miller Bros., bringing the whole troupe from Oklahoma out to California via train. The show consisted of 300 cowboys and cowgirls; 600 horses, cattle and other livestock (including steers and bison) and a whole Sioux tribe (200 of them in all) who set up their teepees on the property. They were then renamed "The Bison-101 Ranch Co.", and specialized in making westerns released under the name World Famous Features.

When construction was completed, the streets were lined with many types of structures, from humble cottages to mansions, mimicking the style and architecture of different countries.[14] Extensive outdoor western sets were built and used on the site for several years. According to Katherine La Hue in her book, Pacific Palisades: Where the Mountains Meet the Sea:

Ince invested $35,000 in building, stages and sets ... a bit of Switzerland, a Puritan settlement, a Japanese village ... beyond the breakers, an ancient brigantine weighed anchor, cutlassed men swarming over the sides of the ship, while on the shore performing cowboys galloped about, twirling their lassos in pursuit of errant cattle ... The main herds were kept in the hills, where Ince also raised feed and garden produce. Supplies of every sort were needed to house and feed a veritable army of actors, directors and subordinates.

While the cowboys, Native Americans and assorted workmen lived at "Inceville", the main actors came from Los Angeles and other communities as needed, taking the red trolley cars to the Long Wharf at Temescal Canyon, where buckboards conveyed them to the set.

Ince lived in a house overlooking the vast studio, later the location of Marquez Knolls. Here he functioned as the central authority over multiple production units, changing the way films were made by organizing production methods into a disciplined system of filmmaking.[15] Indeed, "Inceville" became a prototype for Hollywood film studios of the future, with a studio head (Ince), producers, directors, production managers, production staff, and writers all working together under one organization (the unit system) and under the supervision of a General Manager, Fred J. Balshofer.

Before this, the director and cameraman controlled the production of the picture, but Ince put the producer in charge of the film from inception to final product. He defined the producer's role in both a creative and industrial sense. He was also one of the first to hire a separate screenwriter, director, and editor (instead of the director doing everything themselves). By 1913, the concept of the production manager had been created. With the aid of George Stout, an accountant for NYMP, Ince re-organized how films were outputted to bring discipline to the process. After this adjustment the studio's weekly output increased from one to two, and later three two-reel pictures per week, released under such names as "Kay-Bee" (Kessel-Baumann), "Domino" (comedy), and "Broncho" (western) productions. These were written, produced, cut, and assembled, with the finished product delivered within a week. By enabling more than one film to be made at a time, Ince decentralized the process of movie production to meet the increased demand from theaters. This was the dawning of the assembly-line system that all studios eventually adopted.

With this model, developed between 1913 and 1918, Ince gradually exercised even more control over the film production process as a director-general. In 1913 alone, he made over 150 two-reeler movies, mostly Westerns, thereby anchoring the popularity of the genre for decades. While many of Ince's films were praised in Europe, many American critics did not share this high opinion. One such picture was The Battle of Gettysburg (1913) which was five reels long. The picture helped bring into vogue the idea of the feature-length film. Another important early movie for Ince was The Italian (1915), which depicted immigrant life in Manhattan. Two of his most successful films were among his first, War on the Plains (1912) and Custer's Last Fight (1912), which featured many Native Americans who had actually been in the battle.

Even though he was the first producer-director and directed most of his early productions, by 1913 Ince eventually ceased full-time directing to concentrate on producing,[16] transferring this responsibility to such proteges as Francis Ford and his brother John Ford, Jack Conway, William Desmond Taylor, Reginald Barker, Fred Niblo, Henry King and Frank Borzage.[17] The story was the preeminent aspect of Ince's pictures. Films such as The Italian, The Gangsters and the Girl (1914), and The Clodhopper (1917) are excellent examples of the dramatic structure that resulted from his masterful editing. Film preservationist David Shepard said of Ince in The American Film Heritage:

(He) did everything. He was so proficient at every aspect of film making that even films he didn't direct have the Ince-print, because he exercised such tight control over his scripts and edited so mercilessly that he could delegate direction to others and still get what he wanted. Much of what Ince contributed to the American film took place off the screen; he established production conventions that persisted forbears, and, though his career in films lasted only fourteen years, his influence far outlived him.

Ince also discovered many talents, including his old actor friend, William S. Hart, who made some of the best early westerns, beginning in 1914. Later, a rift developed between the two over sharing of profits.[18] Portentously, on January 16, 1916, a few days after the opening of his first Culver City studio, a fire broke out at "Inceville", the first of many that eventually destroyed all of the buildings. Ince later gave up on the studio and sold it to Hart, who renamed it "Hartville." Three years later, Hart sold the lot to Robertson-Cole Pictures Corporation, which continued filming there until 1922. La Hue writes that "the place was virtually a ghost town when the last remnants of "Inceville" were burned on July 4, 1922, leaving only a "weatherworn old church, which stood sentinel over the charred ruins."

Ince-Triangle Studios

[edit]

By 1915, Ince was considered one of the best-known producer-directors. Around this time, real estate mogul Harry Culver noticed Ince shooting a western in Ballona Creek. Impressed with his talents, Culver convinced Ince to move from Inceville and re-locate to what was to become Culver City. Taking Culver's advice, Ince left NYMP and on July 19 partnered with D.W. Griffith and Mack Sennett to form The Triangle Motion Picture Company based on their prestige as producers. Triangle (so named because from an aerial point of view the property had a triangular shape) was built at 10202 West Washington Boulevard (which became the Ince/Triangle Studios, before becoming Lot 1 of the prestigious MGM Studios, and is now Sony Pictures Studios) as a result the aftermath of Griffith's The Birth of a Nation.[19] Although a box-office success, the film led to riots in major northern cities due to its controversial content.

Triangle was one of the first vertically integrated film companies. By combining production, distribution, and theater operations under one roof, the partners created the most dynamic studio in Hollywood. They attracted directors and stars of the day, including Pickford, Lillian Gish, Roscoe "Fatty" Arbuckle, and Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. They also produced some of the most enduring films of the silent era, including the Keystone Cops comedy franchise. Originally a distributor of films produced by NYMP, the Reliance Motion Picture Corp., Majestic Motion Picture Co., and The Keystone Film Co., by November 1916 the company's distribution was handled by Triangle Distributing Corporation.

Though Ince had many credits as a director at Triangle, he only supervised the production of most pictures, working primarily as executive producer. One of his important pictures as a director was Civilization (1916), an epic plea for peace and American neutrality set in a mythical country and dedicated to the mothers of those who died in World War I. The film competed with Griffith's famous epic, Intolerance and beat it at the box office. Civilization was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".

Ince added a few stages and an administration building to Triangle Studios before selling his shares to Griffith and Sennett in 1918. Three years later, the studios were acquired by Goldwyn Pictures, and in 1924 the facility became Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios. Although many believe that such classics as Gone with the Wind and King Kong were later filmed on that same lot, those movies in fact had been shot at 9336 West Washington Blvd at the Thomas H. Ince Studios.

Thomas H. Ince Studios

[edit]

For a while, Ince joined competitor Adolph Zukor to form Paramount-Artcraft Pictures (later Paramount Pictures). However, he yearned to go back to running his own studio. On July 19, 1918, following Samuel Goldwyn's acquisition of the Triangle lot, he purchased a 14-acre (57,000 m2) property at 9336 West Washington Blvd. on an option basis from Culver along with a $132,000 loan. Thus was formed Thomas H. Ince Studios, which operated from 1919 to 1924. (The area later known as RKO Forty Acres was southeast of the studio.) Ince Studios was to be another Culver City historic landmark.[20] When Ince conceived the idea of building his own studio, he was determined to have it different from the others. Plans submitted to him by architects Meyer & Holler, included having a whole front administrative building made into a replica of George Washington's home at Mount Vernon. The resulting administration building, known as "The Mansion", was the first building on the lot.

In back of the impressive office building were approximately 40 buildings, most of which were designed in the Colonial Revival style. A small group of bungalows, built for various movie stars and designed in styles popular in the 1920s and '30s, were constructed on the west side of the lot. By 1920, two glass stages, a hospital, fire department, reservoir/swimming pool, and the back lot were completed. That same year, President Woodrow Wilson took a tour of the studios as did the King and Queen of Belgium, along with their son, Prince Leopold, among much pomp and ceremony.[citation needed]

Ince had two or three companies working continuously on the lot at any given time. According to film historian Marc Wanamaker, Ince worked with a team of eight directors but "he retained creative control of his films, developing the shooting scripts" and personally assembling each of his films.[2] By now, Ince had drifted away from westerns in favor of social dramas and he made a few significant films including Anna Christie (1923), based on the play by Eugene O'Neill, and Human Wreckage (1923), which was an early anti-drug film starring Dorothy Davenport (widow of addicted star Wallace Reid).

Although Ince found distribution for his films through Paramount and MGM, he was no longer as powerful as he once had been and tried to regain his status in Hollywood. In 1919, with several other independent entrepreneurs (notably his old partner at Triangle, Mack Sennett, Marshall Neilan, Allan Dwan and Maurice Tourneur) he co-founded the independent releasing company, Associated Producers, Inc., to distribute their films. However, Associated Producers merged with First National in 1922.

Though Ince still made some significant motion pictures, the studio system was starting to take over Hollywood. With little room for an independent producer and despite his attempts, Ince could not regain the powerful standing he once held in the industry. He and other independent producers tried to form the Cinematic Finance Corporation in 1921, which made loans to producers who already had been successful, but only accomplished its goal in a limited sense.

In 1925, a year after Ince's death, the studio was sold (with Pathé America) to Ince's friend Cecil B. DeMille. Besides DeMille, among those who had offices on the lot were producer Howard Hughes and Selznick International Pictures. About four years later, DeMille sold his interest to Pathé and the studio became known as the Pathé Culver City Studio. By 1928 after mergers, the studio became RKO/Pathé. By 1957, a number of other studios followed: Desilu Culver, Culver City Studios, Laird International Studios, etc.

In 1991, Sony Pictures Entertainment purchased the property as the home for its television endeavors, renaming it Culver Studios, and eventually selling it in 2004 to a group of investors; the street intersecting[further explanation needed] the studios was renamed Ince Blvd. The studio is still home to Brooksfilms today.[21]

Death

[edit]

Ince's death at the age of 44 has been the subject of much speculation and scandal, with rumors of murder, mystery and jealousy. The official cause of his death was heart failure, and while witnesses (including his widow Nell) corroborate that his medical condition brought about his death, rumors and sensationalism continued decades later, fueled by the 2001 release of the film The Cat's Meow.

In late 1924, Ince and William Randolph Hearst had been negotiating a deal under which Hearst's Cosmopolitan Productions would lease Ince's studio. On Saturday November 15, Hearst visited Ince's "Dias Dorados" estate at 1051 Benedict Canyon Drive[22] and invited him for a weekend cruise on his yacht Oneida to honor Ince's birthday and to work out details of the Cosmopolitan deal.[5]

According to Ince's widow, Nell, Ince took a train to San Diego, where he joined the other guests the following morning. At dinner that Sunday night, the group celebrated Ince's birthday, but afterward Ince suffered an acute bout of indigestion due to his consumption of salted almonds and champagne, both forbidden as he had peptic ulcers. Accompanied by Dr. Goodman, a licensed though non-practicing physician, Ince traveled by train to Del Mar, where he was taken to a hotel and given medical treatment by a second doctor and a nurse. Ince then summoned Nell and his personal physician, Dr. Ida Cowan Glasgow, with Ince's eldest son William accompanying them. The group traveled by train to his Los Angeles home, where Ince died. Nell said that Ince had been treated for chest pains caused by angina, but years later his son William became a physician and said that his father's illness resembled thrombosis.[23]

Dr. Glasgow signed the death certificate citing heart failure as the cause of death. The front page of the Wednesday morning Los Angeles Times supposedly sensationalized the story: '"Movie Producer Shot on Hearst Yacht!",[24][further explanation needed][better source needed] but the headlines vanished in the evening edition. On November 20, the Times published Ince's obituary citing heart disease as the cause of death along with his failing health from an automobile accident two years earlier.[25] A month later, the New York Times reported that the San Diego district attorney had announced that Ince's death was caused by heart failure and no further investigation was necessary.[26] Both Ince and his wife were practicing Theosophists who preferred cremation and had arranged for it long before his death.[23] While rumors prevailed that Nell suddenly departed the country after her husband's death, she actually left for Europe about seven months later in July 1925.[5]

However, several conflicting stories circulated about the incident, often revolving around a claim that Hearst shot Ince in the head after mistaking him for Charlie Chaplin. Chaplin's valet, Toraichi Kono, claimed to have seen Ince when he came ashore via stretcher in San Diego. Kono told his wife that his head was "bleeding from a bullet wound." The story quickly spread among Japanese domestic workers throughout Beverly Hills.[27] Charles Lederer, the nephew of Hearst's longtime partner Marion Davies, told a similar story to Orson Welles, who in turn told Peter Bogdanovich, the director of The Cat's Meow.[28] Elinor Glyn, who was present aboard Oneida, told Eleanor Boardman that everyone aboard the yacht had been sworn to secrecy about the events, which would indicate more than a death by natural causes.[29] Contrary to these accounts, during Ince's funeral, the Los Angeles Times reported that his casket would remain open for one hour "to afford friends and studio employees to pass for one last glimpse of the man they loved and respected", with no witnesses ever mentioning a bullet wound.[30][31] Ince's body was cremated on November 21 in Hollywood Forever Cemetery and the ashes returned to his family on December 24, 1924, who reportedly scattered them at sea.[32]

Hearst movie columnist Louella Parsons' name also figured into the Ince scandal, with some speculating that she had been aboard Oneida during the reported shooting. Supposedly, after the Ince affair, Hearst gave her a lifetime contract and expanded her syndication. However, other sources show that Parsons did not gain her position with Hearst as part of "hush money" but had been the motion picture editor of the Hearst-owned New York American in December 1923 and her contract was signed a year before Ince's death.[5] Another story circulated that Hearst provided Nell with a trust fund just before she left for Europe and that Hearst paid off Ince's mortgage on his Château Élysée apartment building in Hollywood. However, Nell was left a very wealthy woman and the Château Élysée was an apartment she had already owned and had built on the grounds where the Ince estate once stood.[23][failed verification]

Years later, Hearst spoke to a journalist about the rumor that he had murdered Ince. "Not only am I innocent of this Ince murder," he said, "So is everybody else." Nell herself was increasingly frustrated over the rumors surrounding her husband's death and remarked: "Do you think I would have done nothing if I even suspected that my husband had been victim of foul play on anyone's part?"[23] Still, the myth of Ince's death overshadowed his reputation as a pioneering filmmaker and his role in the growth of the film industry. His studio was sold soon after he died. His final film, Enticement, a romance set in the French Alps, was released posthumously in 1925.

In popular culture

[edit]Murder at San Simeon (Scribner), a 1996 novel by Patricia Hearst (William Randolph's granddaughter) and Cordelia Frances Biddle, is a mystery based on the 1924 death of producer Thomas Ince aboard the yacht of William Randolph Hearst. This fictitious version presents Chaplin and Davies as lovers and Hearst as the jealous old man unwilling to share his mistress.

RKO 281 is a 1999 film about the making of Citizen Kane. The movie includes a scene depicting screenwriter Herman Mankiewicz telling director Orson Welles his account of the incident.

The Cat's Meow, the 2001 film directed by Peter Bogdanovich, is another fictitious version of Ince's death. Bogdanovich notes that he heard the story from director Orson Welles, who said he heard it from screenwriter Charles Lederer (Marion Davies's nephew).[33] In Bogdanovich's film, Ince is portrayed by Cary Elwes. The movie was adapted by Steven Peros from his own play, which premiered in Los Angeles in 1997.

Ince's star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame is located at 6727 Hollywood Blvd. in Los Angeles.

The Silver Sheet

[edit]A studio publication promoting Thomas H. Ince Productions.

-

The Silver Sheet (1920)

-

Hail the Woman (1921)

-

Skin Deep (1922)

-

Lorna Doone (1922)

-

Scars of Jealousy (1923)

-

Bell Boy 13 (1923)

-

The Galloping Fish (1924)

-

Soul of the Beast (1923)

-

Anna Christie (1923)

-

What a Wife Learned (1923)

-

A Man of Action (1923)

-

Her Reputation (1923)

-

Idle Tongues (1924)

-

The Marriage Cheat (1924)

-

Enticement (1925)

-

Those Who Dance (1924)

-

Playing with Souls (1925)

Filmography, posters and newspaper ads

[edit]-

The Battle of Gettysburg (1913)

-

The Wrath of the Gods (1914)

-

The Italian (1915)

-

The Return of Draw Egan (1916)

-

The Phantom (1916)

-

Triangle-Keystone comedies (1916)

-

The Aryan (1916)

-

Civilization (1916)

-

Civilization Peace Song (1916)

-

Civilization (1916)

-

Hell's Hinges (1916)

-

Aloha Oe (1916)

-

Peggy (1916)

-

False to the Finish (1917)

-

Haunted by Himself (1917)

-

Her Busted Debut (1917)

-

Mystic Faces (1918)

-

Wagon Tracks (1919)

-

Child of M'sieu (1919)

-

Silk Hosiery (1920)

-

Her Husband's Friend (1921)

-

Lorna Doone (1922)

Notes

[edit]- ^ "US World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918 Thomas Harper Ince". FamilySearch.org. Although in later years Ince would remove two years from his age, he wrote on his Draft Registration Card that he was born in 1880. His christening records also show a birth date of 1880. "Rhode Island Birth and Christenings, 1600–1914". FamilySearch.org.

- ^ a b Wanamaker, Marc (1982). "Thomas H. Ince, Father of the Western". The Movie, pp. 2170–2172.

- ^ Cerra, Julie Lugo; Wanamaker, Marc (14 March 2011). Our Favorite Things p. 62-70. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781439640647. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ^ "The Culver Studios". theculverstudios.com.

- ^ a b c d Taves, Brian. (2012). Thomas Ince: Hollywood's Independent Producer. The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-3423-9. Retrieved 10 January 2016. Taves' extensive biography contains a strong rebuttal to the much rumored murder of Thomas Ince; see pp. 1-13.

- ^ Emma Brennan Ince;(mother of Thomas) Internet Broadway Database

- ^ Flom, Eric L. (5 March 2009). Silent Film Stars on the Stages of Seattle: A History of Performances by Hollywood Notables; p. 89-90. Mcfarland & Co Inc. ISBN 9780786439089. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ^ a b c Ince, Thomas H. (13 Dec 1924). "In The Movies – Yesterday and Today". Los Angeles Record. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ^ "Special Collections – Margaret Herrick Library – Academy of Motion Picture Arts & Sciences". oscars.org.

- ^ "MoMA". moma.org.

- ^ a b Stephens, E. J.; Wanamaker, Marc (10 Nov 2014). Early Poverty Row Studios p. 19. Arcadia Publications. ISBN 9781439648292. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ^ a b McVeigh, Stephen (14 Feb 2007). The American Western p. 62. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748629442. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ^ "Inceville". movielocationsplus.com. Archived from the original on 2021-03-03. Retrieved 2015-06-09.

- ^ Soares, Andre (2014-01-24). "Inceville: Film Pioneer Thomas Ince's Studios". Altfg.com. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- ^ Thomas H. Ince -- Encyclopædia Britannica [www.britannica.com]

- ^ "The Return of Thomas H. Ince". MoMA. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- ^ a b "Thomas H. Ince – Writer – Films as Director (selected list):, Films as Producer:, Films as Actor:, Publications". filmreference.com.

- ^ The Backlot Film Festival – History – Thomas Ince Biography Archived 2008-02-10 at the Wayback Machine at www.backlotfilmfestival.com

- ^ "D. W. Griffith: Hollywood Independent". Cobbles.com. 1917-06-26. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- ^ "History – The Culver Studios". theculverstudios.com.

- ^ "Home". Ericowenmoss.com. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- ^ "Half Pudding Half Sauce: "Dias Dorados" – A Country House in Early Californian Style". halfpuddinghalfsauce.blogspot.ca. 6 November 2012.

- ^ a b c d Rogers St. Johns, Adela (1969). The Honeycomb. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, Inc., pp.185-193. Rogers St. Johns was a journalist, screenwriter, and personal friend of Elinor and Thomas Ince.

- ^ Los Angeles Times. November 16, 1924 (morning edition. No record is available of this article on November 16.

- ^ "Thomas H. Ince, Pioneer of Films, Called By Death: Heart Disease Proves Fatal to Screen Magnate After Sudden Attack at Yacht Party". Los Angeles Times. November 20, 1924.

- ^ "Ince's Death Natural, Prosecutor Asserts". The New York Times. December 11, 1924.

- ^ "Los Angeles News and Events". LA Weekly. 2013-10-03. Retrieved 2014-02-15.

- ^ "Peter Bogdanovich on completing Orson Welles long awaited 'The Other Side of the Wind'". Wellesnet | Orson Welles Web Resource. 2008-03-15. Retrieved 2020-09-11.

- ^ "Hollywood Confidential". Jonathan Rosenbaum. 2002-06-28. Archived from the original on 2020-09-23. Retrieved 2020-09-11.

- ^ "Ince Will Lie in State One Hour". Los Angeles Times. November 21, 1924.

- ^ "Film World Mourns Ince". Los Angeles Times. November 22, 1924.

- ^ Wilson, Scott (2016-08-19). Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed. McFarland. p. 365. ISBN 978-1-4766-2599-7.

- ^ French, Lawrence, "Peter Bogdanovich on Completing Orson Welles Long Awaited The Other Side of the Wind for Showtime" (March 9, 2008 interview). Wellesnet: The Orson Welles Web Resource, March 14, 2008. Retrieved 5 January 2013

References

[edit]- Aleiss, Angela (2005). "Hollywood and the Silent American: Life in Inceville". Making the White Man's Indian: Native Americans and Hollywood Movies. Westport CT: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-98396-X.

- Hall Kaplan, Margaret (February 12, 1984). "Inceville: Key Site for Film Pioneers". Los Angeles Times.

- Higgins, Steve (1989). "Thomas H. Ince: American Filmmaker". In MacCann, Richard Dyer (ed.). The First Film Makers. Metuchen, NJ: The Scarecrow Press.

- Taves, Brian (2011). Thomas Ince: Hollywood's Independent Pioneer. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-3422-2.

- Wanamaker, Marc (1982). "Thomas H. Ince, Father of the Western". The Movie. No. 102. pp. 2170–2172.

- Wanamaker, Marc (Summer 1973). "The Western at Inceville:1912". Views and Reviews. No. 4. pp. 69–76.

External links

[edit]- 1880 births

- 1924 deaths

- American cinema pioneers

- American male screenwriters

- American male silent film actors

- American film production company founders

- American people of English descent

- Writers from Newport, Rhode Island

- Male actors from Rhode Island

- 20th-century American male actors

- Death conspiracy theories

- Film directors from Rhode Island

- Screenwriters from Rhode Island

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American screenwriters

![Child of M'sieu [it] (1919)](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/67/Child_of_M%27sieu.jpg/128px-Child_of_M%27sieu.jpg)