Clorox

Clorox Building, 1221 Broadway, Oakland, California, U.S. | |

| Formerly |

|

|---|---|

| Company type | Public |

| Industry |

|

| Founded | May 3, 1913 |

| Founders |

|

| Headquarters | Clorox Building, Oakland, California , U.S. |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | Linda Rendle (CEO) |

| Products | |

| Brands |

|

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | 8,000 (2024) |

| Website | thecloroxcompany |

| Footnotes / references [1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10] | |

The Clorox Company (formerly Clorox Chemical Company) is an American multinational manufacturer and marketer of consumer and professional products.[11] As of 2024, the Oakland, California-based company had approximately 8,000 employees worldwide. Net sales for the 2024 fiscal year were US$7.1 billion. Ranked annually since 2000, Clorox was named number 474 on Fortune magazine's 2020 Fortune 500 list.

Clorox products are sold primarily through mass merchandisers, retail outlets, e-commerce channels, distributors, and medical supply providers.[12] Clorox brands include its namesake bleach and cleaning products as well as Burt's Bees, Formula 409, Glad, Hidden Valley, Kingsford, Kitchen Bouquet, KC Masterpiece, Liquid-Plumr, Brita (in the Americas), Mistolin, Pine-Sol, Poett, Green Works Cleaning Products, Soy Vay,[13][14] RenewLife,[15] Rainbow Light, Natural Vitality, Neocell,[16] Tilex, S.O.S., and Fresh Step, Scoop Away, and Ever Clean pet products.[13][14]

History

[edit]1913–1927

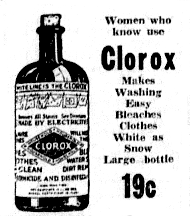

[edit]The Electro-Alkaline Company[17] was founded on May 3, 1913, as the first commercial-scale liquid bleach manufacturer in the United States. Archibald Taft, a banker; Edward Hughes, a purveyor of wood and coal; Charles Husband, a bookkeeper; Rufus Myers, a lawyer; and William Hussey, a miner, each invested $100 to set up a factory on the east side of San Francisco Bay.[17] The name of its original product, Clorox, was coined as a portmanteau of its two main ingredients, chlorine and sodium hydroxide. The original Clorox packaging featured a diamond-shaped logo, which has been used in one form or another in Clorox branding ever since.

The public, however, was unfamiliar with liquid bleach. The company started slowly and was about to collapse when investor William Murray took it over in 1916, who installed himself as general manager. His wife Annie prompted the creation of a less concentrated liquid bleach for home use and built customer demand by giving away 15-US-fluid-ounce (440 ml) sample bottles at the family's grocery store in downtown Oakland.[18] Word shortly began to spread, and in 1917 the company started shipping Clorox bleach to the East Coast via the Panama Canal.

1928–1960s

[edit]On May 28, 1928, the company went public on the San Francisco stock exchange. It changed its name to Clorox Chemical Company. Butch, an animated Clorox liquid bleach bottle, was used in its advertising and became well known, even surviving the 1941 transition from rubber-stoppered bottles to screw-off caps.[19]

Clorox was strong enough to survive the Great Depression during the 1930s, achieving national distribution of its bleach.

Even though bleach was a valuable first aid product for American armed forces during World War II, government rationing of chlorine gas forced many bleach manufacturers to reduce the concentration of sodium hypochlorite in their products. Clorox, however, declined and elected to sell fewer units of full-strength bleach, establishing a reputation for quality.[19]

In 1957, Clorox was purchased by Procter & Gamble, which renamed its new subsidiary the Clorox Company. Almost immediately, a rival company objected to the purchase, and it was challenged by the Federal Trade Commission, which feared it would stifle competition in the household products market. The FTC prevailed in 1967 when the U.S. Supreme Court forced Procter & Gamble to divest Clorox,[20][21] which took place on January 1, 1969.

1970s–1990s

[edit]Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Clorox pursued an aggressive expansion and diversification program. In 1970 it introduced Clorox 2 all-fabric bleach. Later it acquired several brands that remain a part of its portfolio, including Formula 409, Liquid-Plumr, and Kingsford charcoal. The company also developed new cleaning products such as Tilex instant mildew remover.[22] It also acquired the "Hidden Valley" brand of ranch dressing.

In 1988, Clorox struck a licensing-and-distribution agreement that brought Brita water filters to the U.S.[23] The company acquired sole control of the brand for the U.S. and Canada in 1995 when it acquired Brita International Holdings (Canada). In 2000 it secured the remaining Americas market from Brita.[24]

In 1990, Clorox purchased Pine-Sol.[23]

In 1999, Clorox acquired First Brands, the former consumer products division of Union Carbide, in the largest transaction in its history. Such brands as Glad, Handi-Wipes (which First Brands acquired from Colgate-Palmolive several months before the Clorox acquisition), and STP became part of the Clorox portfolio. The First Brands acquisition doubled the company's size and helped it land on the Fortune 500 for the first time the following year.[23]

2000s–present

[edit]In 2002, Clorox entered into a joint venture with Procter & Gamble to create food and trash bags, food wraps, and containers under the names Glad, GladWare, and related trademarks.[25] As part of this agreement, Clorox sold a 10% stake in the Glad products to P&G, which increased to 20% in 2005.[26]

In 2007, the company acquired Burt's Bees.[27] In 2010, Clorox shed businesses that were no longer a good strategic fit for the company, announcing that it was selling the Armor All and STP brands to Avista Capital Partners.[28] In 2011, Clorox acquired the Aplicare and HealthLink brands, bolstering its presence in the healthcare industry.[29]

In 2008, the Clorox Company became the first major consumer packaged goods company to develop and nationally launch a green cleaning line, Green Works, into the mainstream cleaning aisle.[30] In 2011, the Clorox Company integrated corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting with financial reporting. The company's annual report for the fiscal year ending in June 2011 shared data on financial performance and advances in environmental, social, and governance performance.[31]

In 2013, the company announced a focus on consumer megatrends that included sustainability, health and wellness, affordability and value, and multiculturalism, with a particular emphasis on the Hispanic community.[32]

In 2015, the company became a signatory of the United Nations Global Compact, a large corporate responsibility initiative.[33]

In 2018, Clorox purchased Nutranext Business, LLC for approximately $700 million. Florida-based Nutranext makes natural multivitamins, specialty minerals used as health aids, and supplements for hair, skin and nails.[34] Operating income in 2018 was US$1.1 billion.[35] The company had approximately 8,700 employees worldwide as of 2018, yearly revenue for the period ending June 30, 2018, equaled $6.1 billion.[10] Yearly revenue equaled $6.2 billion in 2019.[7]

Clorox was named to the inaugural Bloomberg Gender Equality Index in 2018.[36] The following year, it topped the Axios Harris Poll 100 corporate reputation rankings.[37] In 2019, Clorox ranked seventh in Barron's "100 Most Sustainable U.S. Companies" list.[38]

In 2022, the company opened a new manufacturing facility in Martinsburg, West Virginia, to facilitate the growth of its cat litter business.[39]

In 2023 the company was affected by a cyberattack, resulting in revenue loss and product shortages.[40]

Brands

[edit]

The Clorox Company currently owns a number of well-known household and professional brands across a wide variety of products, among them are the following:

- Brita water filtration systems (Americas only)[13][41]

- Burt's Bees natural cosmetics and personal care products[13]

- Clorinda: bleach and cleaning and disinfection products, alternative brand of Clorox Chile[13]

- Formula 409 hard surface cleaners[13]

- Fresh Step, Scoop Away and Ever Clean cat litters[13]

- Glad storage bags, trash bags, Press'n Seal, GladWare containers (joint venture with P&G as 20% minority shareholder)[13]

- Green Works natural cleaners[13]

- Handy Andy floor cleaners in Australia[42]

- Hidden Valley dressings, sandwich spreads and condiments, dips and dressing mixes, croutons and salad toppings, side dishes and appetizers[13]

- Kingsford charcoal[13]

- Kitchen Bouquet, KC Masterpiece, and Soy Vay sauces[13]

- Lestoil heavy-duty laundry / multipurpose Cleaner[13]

- Liquid-Plumr drain cleaner[13]

- Natural Vitality[16]

- Neocell dietary supplements[16]

- Pine-Sol, Tilex, Poett and S.O.S cleaning products[13]

- Rainbow Light[16]

- Renew Life digestive health products[15]

The ingredients in Clorox bleach are water, sodium hypochlorite, sodium chloride, sodium carbonate, sodium chlorate, sodium hydroxide and sodium polyacrylate.[43]

For historical reasons, and in certain markets, the company's bleach products are sold under regional brands. In 2006, Clorox acquired the Javex line of bleach products in Canada, and similar product lines in parts of Latin and South America, from Colgate-Palmolive.[44]

Sales

[edit]The company ranked No. 453 on the Fortune 500 list in 2017;[45][46][47][48] by 2020, Clorox ranked No. 474 on the list.[49]

Clorox's net sales (2015–2020)

| FY 2020 | FY 2019 | FY 2018 | FY 2017 | FY 2016 | FY 2015 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. dollars (in millions) | $6,721[50] | $6,214[7] | $6,124[10] | $5,973[51] | $5,761[48] | $5,655[52] |

Marketing

[edit]Advertising campaigns

[edit]In 1986, the advertising campaign for Clorox 2 featured an award-winning jingle, "Mama's Got The Magic of Clorox 2". The song was written by Dan Williams and performed by Dobie Gray.[53][54][55]

The company was listed at Advertising Age's 2015 Marketer A-List.[56][57]

Allegations of sexist marketing

[edit]During 2006 and 2007, a Clorox commercial that aired nationally showed several generations of women doing laundry. The commercial included the words "Your mother, your grandmother, her mother, they all did the laundry, maybe even a man or two". Feminists criticized the commercial for insinuating that doing laundry is a job for women only.[58][59]

The Clorox slogan, "Mama's got the magic of Clorox", was criticized on similar grounds.[60] The slogan first appeared in a Clorox commercial in 1986.[61] A modified version of the commercial ran from 2002 to 2004.[62]

In 2009, Clorox received complaints of sexism for an advertisement that featured a man's white, lipstick-stained dress shirt with the caption, "Clorox. Getting ad guys out of hot water for generations".[63] The ad, and others, were produced expressly for the television program Mad Men, capitalizing on "the show's unique vintage style to [create] a link between classic and modern consumer behaviors".[64]

Reactions to product claims

[edit]Green Works

[edit]In 2008, the Sierra Club endorsed the Clorox Green Works line. Sierra Club Executive Director Carl Pope stated that one of the nonprofit organization's primary goals is to "foster vibrant, healthy communities with clean water and air that are free from pollution. Products like Green Works help to achieve this goal in the home". The Sierra Club also partnered with Clorox to "promote a line of natural cleaning products for consumers who are moving toward a greener lifestyle".[65] The partnership "caused schisms" in the club, which contributed in part to Pope's decision to resign.[66]

Also in 2008, the National Advertising Division told Clorox to either discontinue or modify its advertisements for Green Works on the grounds the cleaners actually do not work as well as traditional cleaners, as Clorox had claimed.[67]

In 2009, Clorox received further criticism for its Clorox Green Works line, regarding claims the products are environmentally friendly.[68] Several Clorox Green Works products contain ethanol, which environmental groups state is neither cost-effective nor eco-friendly.[68] Many Green Works products also contain sodium lauryl sulfate, a known skin irritant.[68] Women's Voices for the Earth have questioned whether or not the Clorox Green Works line is greenwashing, as Clorox's "green" products are far outnumbered by their traditional products, asking "Why sell one set of products that have hazardous ingredients and others that don't?"[30]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "FY 2024 Annual Report (Form 10-K)". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. August 8, 2024.

- ^ "The Clorox Company Profile". Yahoo Finance. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ Dulaney, Chelsey (May 15, 2015). "Former Clorox CEO Knauss Leaving Executive Chairman Post". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "Clorox shuffles boardroom as CEO adds chairman's role". San Francisco Business Times. August 4, 2016. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ Avalos, George (September 18, 2014). "Clorox names Dorer as new CEO". San Josey Mercury News. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ Dulaney, Chelsey (May 15, 2015). "Former Clorox CEO Knauss Leaving Executive Chairman Post". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Clorox Reports Q4 and Fiscal Year 2019 Results, Provides Fiscal Year 2020 Outlook".

- ^ "Clorox Reports Q4 and Fiscal Year 2018 Results, Provides Fiscal Year 2019 Outlook".

- ^ "Clorox". Fortune. Retrieved December 31, 2018.[dead link]

- ^ a b c NASDAQ stock report

- ^ "Consolidated Statement of Earnings, The Clorox Company". Yahoo Finance. December 4, 2014. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ^ "Clorox Company (The) Stock Report". NASDAQ. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Our Brands". The Clorox Company. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

- ^ a b Morgan, Penny (November 30, 2015). "How Is Clorox Improving Product Distribution?". Market Realist. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ a b Wahba, Phil. "Clorox Wants to Help Clean Up Your Digestion". Fortune. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Big Deal: Clorox to Buy Nutranext for $700 Million". March 13, 2018. Archived from the original on December 9, 2018. Retrieved December 8, 2018.

- ^ a b Clorox company history, page 1 Archived December 3, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Timeline – The Clorox Company". thecloroxcompany.com. August 2, 2016. Archived from the original on August 17, 2016. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ a b Clorox company history, page 3 Archived November 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ FTC v. Procter & Gamble Co., 386 U.S. 568 (1967).

- ^ "P&G ordered to sell Clorox". Chemical & Engineering News Archive. 45 (17): 22. April 17, 1967. doi:10.1021/cen-v045n017.p022.

- ^ "Timeline | The Clorox Company". August 3, 2016. Retrieved October 12, 2021.

- ^ a b c "The Clorox Company Heritage Timeline". The Clorox Company. Archived from the original on August 13, 2021. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

- ^ "Clorox Secures Brita Business In Americas". HomeWorld Business. November 27, 2000. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- ^ "Company News; Clorox and P&G Plan Joint Venture for Glad Products". The New York Times. Bloomberg News. November 15, 2002. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

- ^ "Clorox and Procter & Gamble Announce Increased P&G Investment in Glad Products Joint Venture". The Clorox Company. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

- ^ "Clorox To Pay $950 Million For Burt's Bees". Environmental Leader. November 2007. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

- ^ Coleman-Lochner, Lauren (September 21, 2010). "Clorox to Sell Auto-Care Businesses for $780 Million". Bloomberg News. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

- ^ Brown, Steven E.F. "Clorox buys Aplicare and HealthLink for about $80 million".[dead link]

- ^ a b DeBare, Ilana (January 14, 2008). "Clorox introduces green line of cleaning products". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 28, 2014.

- ^ "Clorox Identifies Four Mega Trends For Hispanic Consumers". The Shelby Report. March 13, 2013. Retrieved February 22, 2014.

- ^ "The Clorox Company". United Nations Global Compact. 2015. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "Clorox Announces Agreement to Acquire Nutranext, a Leader in Dietary Supplements". thecloroxcompany.com. The Clorox Company. November 9, 2017. Archived from the original on November 28, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ NASDAQ income-statement

- ^ "Bloomberg Gender-Equality Index Doubles in Size, Recognizing 230 Companies Committed to Advancing Women in the Workplace" January 16, 2019.

- ^ "The Axios Harris Poll 100 reputation rankings: The Corona companies" July 30, 2020.

- ^ "Burt's Bees Helps Clorox Create Eco-Friendly Buzz". Alabrava.net. March 16, 2020. Archived from the original on March 18, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2020.

- ^ "Clorox opens state-of-the-art cat litter manufacturing plant in West Virginia" WV News, October 21, 2022.

- ^ "Clorox, reeling from cyberattack, expects quarterly loss". Reuters. October 4, 2023. Retrieved October 14, 2023.

- ^ Carr, Coeli (May 20, 2010). "Pouring It On". Time. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ^ Article in "The Australian Financial Review

- ^ "Ingredients Inside". The Clorox Company. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ^ Clorox press release Archived December 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, December 20, 2006

- ^ "Fortune 500 Companies 2017: Who Made the List". Fortune. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "2016 Fortune 500". Fortune. December 2016. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- ^ "CLX Company Financials". NASDAQ. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ a b "Clorox Company (The) Stock Report". NASDAQ. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ "Fortune 500 2020". Fortune. Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ^ "Clorox Revenue 2006-2021". Macrotrends. Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ^ http://www.nasdaq.com/symbol/clx/stock-reporton June 30, 2017 Archived January 22, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Clorox Income Statement". Yahoo Finance. June 30, 2015. Retrieved December 30, 2015.

- ^ "You know Dobie's voice even if you don't know his name". The Tennessean. "That's Gray's unmistakable, heart-tugging tenor singing the award-winning "Mama's got the magic" Clorox ad jingle."

- ^ "Country stars shine in world of jingles". Newspapers.com. The Record. 1991. "Dobie Gray sang the reggae "Mama's Got the Magic in Clorbx II," which Williams wrote."

- ^ "The Jingle Biz". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ "Ad Age's 2015 Marketer A-List". Advertising Age. December 7, 2015. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ Neff, Jack (December 7, 2015). "Clorox Starts Agency Review That Could Consolidate Lead, Digital Duties". Advertising Age. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- ^ Wallace, Kelsey (August 31, 2009). "Mad Men's Portrayal of Sexism Seeps Unironically into Its Commercial Breaks". Bitch magazine. Archived from the original on October 5, 2011. Retrieved February 5, 2010.

- ^ "Clorox's history of women's unwaged labor". Feministing. August 27, 2007. Retrieved November 8, 2010.

- ^ Macaulay, Rose (2004). "Women's Work Should Not Be Defined as Housework". In Ellison, Sheila (ed.). If Women Ruled the World: How to Create the World We Want to Live In. Maui, Hawaii: Inner Ocean Pub. p. 65. ISBN 9781577317418. OCLC 713268308.

- ^ "Clorox 2 (1986)". ILoveTVCommercials.com. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ Clorox Automatic Toilet Bowl Cleaner Commercial – February 11, 2002 on YouTube[dead link]

- ^ Wright, Jennifer (September 28, 2009). "Clorox 'Mad Men' Ads Miss the Target". Brandchannel.com. Archived from the original on January 28, 2010. Retrieved February 5, 2010.

- ^ DeClemente, Donna. "Mad Men inspires brands to create some stylish ad campaigns to help kick-off season 3". Donna's Promo Talk. Archived from the original on July 30, 2018. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ "Some in Sierra Club feel sullied by Clorox deal". NBC News. July 16, 2008. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ Sahagun, Louis (November 19, 2011). "Sierra Club leader departs amid discontent over group's direction". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ "NAD Tells Clorox to Clean Up Ads". Environmentalleader.com. August 17, 2008. Archived from the original on February 9, 2010. Retrieved February 5, 2010.

- ^ a b c Tennery, Amy (April 22, 2009). "4 'green' claims to be wary of". MSN. Archived from the original on November 22, 2011. Retrieved February 5, 2010.

External links

[edit]- TheCloroxCompany.com: corporate website

- Clorox.com: consumer products website

- Business data for The Clorox Company:

- Clorox brands

- 1913 establishments in California

- 1960s initial public offerings

- American brands

- American companies established in 1913

- Chemical companies established in 1913

- Chemical companies of the United States

- Cleaning product brands

- Consumer goods

- Companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange

- Companies in the S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrats

- Manufacturing companies based in Oakland, California

- Manufacturing companies established in 1913

- Multinational companies headquartered in the United States