USS Akron

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2008) |

ZRS-4 in flight, 1931

(An airplane is passing over her bow.) | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | USS Akron |

| Ordered | 6 October 1928 |

| Laid down | 31 October 1929 |

| Launched | 8 August 1931 |

| Commissioned | 27 October 1931 |

| Maiden voyage | 23 September 1931 |

| Fate | Crashed in severe weather on 4 April 1933 |

| General characteristics | |

| Tonnage | 221,000 pounds (100 t) |

| Length | 785 feet (239 m) |

| Beam | 132.5 feet (40.4 m) (diameter) |

| Height | 152.5 feet (46.5 m) |

| Propulsion | Eight 560 horsepower (420 kW) gasoline-powered engines mounted internally. |

| Speed |

|

| Range | 10,580 nautical miles (19,590 km; 12,180 mi) |

| Capacity | list error: <br /> list (help) Useful load 182,000 pounds (83 t) Volume 6,500,000 cubic feet (180,000 m3) |

| Complement | 89 officers and men |

| Armament | seven machine guns |

| Aircraft carried | four aircraft |

For information on the 1911 airship constructed by the Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, also called the Akron, see Melvin Vaniman.

USS Akron (ZRS-4) was a rigid helium-filled airship of the United States Navy that crashed off the New Jersey coast early on 4 April 1933, killing 73 crew and passengers. During its brief, accident prone term of service, the airship also served as a flying aircraft carrier, launching Sparrowhawk biplanes.

At 785 feet (239 m) long, 20 ft (6 m) shorter than the Hindenburg, she and her sister, Macon (ZRS-5), were amongst the largest flying objects in the world. Although the Hindenburg was longer, the two airships still hold the world record for helium-filled airships.

Construction and commissioning

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2008) |

Construction of the ZRS-4 commenced on 31 October 1929, at the Goodyear Airdock in Akron, Ohio by the Goodyear-Zeppelin Corporation.[1] On 7 November 1931, Rear Admiral William A. Moffett, Chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, drove the "golden rivet" in the ship's main ring. Erection of the actual hull sections began in March 1930. On 10 May, Secretary of the Navy Charles Francis Adams chose the name Akron and Assistant Secretary of the Navy Ernest Lee Jahncke announced it four days later, on 14 May 1930.

Once completed the Akron could store 20,000 US gallons (76,000 litres) of gasoline, which gave it a range of 10,500 miles (16,900 km).[2] Eight gasoline powered engines were mounted inside the hull. Each engine turned one twin-bladed propeller via a driveshaft which allowed the propeller to swivel vertically and horizontally.[3]

On 8 August 1931, Akron was launched (floated free of the hangar floor) and christened by Mrs. Lou Henry Hoover, the wife of the President of the United States, Herbert Clark Hoover. Akron conducted her maiden flight on the afternoon of 23 September, around the Cleveland, Ohio, area, with Secretary of the Navy Adams and Rear Admiral Moffett embarked. She made eight more flights — principally over Lake Erie but ranging as far as Detroit, Michigan, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Fort Wayne, Indiana, and Columbus, Ohio — before her delivery flight from Akron to the Naval Air Station (NAS) at Lakehurst, New Jersey, where she was commissioned on Navy Day, 27 October, Lieutenant Commander Charles E. Rosendahl in command.

Maiden voyage

On 2 November 1931, Akron cast off for her maiden voyage as a commissioned "ship" of the United States Navy and cruised down the eastern seaboard to Washington. Over the weeks that followed, she amassed 300 hours aloft in a series of flights. Included in these was a 46-hour endurance run to Mobile, Alabama, and back. The return leg of the trip was made via the valleys of the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers.

Participation in a search exercise, January 1932

On the morning of 9 January 1932, Akron cleared Lakehurst to work with the Scouting Fleet on a search exercise. Proceeding to the coast of North Carolina, Akron headed out over the Atlantic, tasked with finding a group of Guantanamo Bay-bound destroyers. Once she had located them, she was to shadow them and report their movements. Clearing the North Carolina coast at 0721 on 10 January, she proceeded south. Bad weather prevented her from sighting the destroyers (she missed contact with them at 1240, although they sighted her), but she kept on, eventually shaping a course toward the Bahamas by late afternoon. Heading northwesterly into the night, Akron then changed course shortly before midnight and proceeded to the southeast. Ultimately, at 0908 on 11 January Akron succeeded in spotting the light cruiser USS Raleigh (CL-7) and a dozen destroyers, positively identifying them on the eastern horizon two minutes later. Sighting a second group of destroyers shortly thereafter, Akron was released from the evolution about 1000, having achieved a "qualified success" in her initial test with the Scouting Fleet.

As historian Richard K. Smith says in his definitive study, The Airships Akron and Macon, "...consideration given to the weather, duration of flight, a track of more than 3,000 miles (4,800 km) flown, her material deficiencies, and the rudimentary character of aerial navigation at that date, the Akron's performance was remarkable. There was not a military airplane in the world in 1932 which could have given the same performance, operating from the same base."

Accident, February 1932

Akron was to have taken part in Fleet Problem XIII, but an accident at Lakehurst on 22 February 1932 prevented her participation. As she was being taken from her hangar, the tail came loose from its moorings and, caught by the wind, crunched into the ground. The heaviest damage was confined to the lower fin area, and required repairs before the ship was ready to go aloft again. In addition, ground handling fittings had been torn out of the main frame, necessitating repairs to those vital elements as well. It was not until later in the spring that Akron was airworthy again. On 28 April, the airship cast off for a flight with Rear Admiral Moffett and Secretary of the Navy Adams aboard. This particular flight lasted nine hours.

Testing of the "spy basket"

Soon after returning to Lakehurst to disembark her distinguished passengers, Akron took off again to conduct a test of the "spy basket" — something like a small airplane fuselage suspended beneath the airship that would enable an observer to serve as the ship's "eyes" below the clouds while the ship herself remained out of sight above them. Fortunately, the basket was "manned" only by a sandbag, for the contraption proved "frighteningly unstable", swooping from one side of the airship to the other before the startled gazes of Akron's officers and men. It was never tried again.

Experimental use as a "flying aircraft carrier"

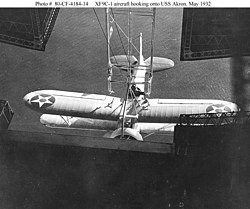

Akron, and her sister Macon (ZRS-5) (still under construction), were regarded as potential "flying aircraft carriers", carrying parasite fighters for reconnaissance. On 3 May 1932, Akron cruised over the coast of New Jersey with Rear Admiral George C. Day, President of the Board of Inspection and Survey, embarked, and for the first time tested the "trapeze" installation for in-flight handling of aircraft. The aviators who carried out those historic "landings," first with a Consolidated N2Y trainer and then with the prototype Curtiss XF9C-1 Sparrowhawk, were Lieutenant Daniel W. Harrigan and Lieutenant Howard L. Young. The following day, Akron carried out another demonstration flight, this time with members of the House Committee on Naval Affairs on board. During this operation the same fliers gave the lawmakers a demonstration of Akron's ability to handle aircraft.

Journey from Lakehurst to the west coast, May 1932

Following the conclusion of those trial flights, Akron departed Lakehurst on 8 May 1932, and set out for the west coast of the United States. The airship proceeded down the eastern seaboard to Georgia thence moved across the gulf plain and continued on over Texas and Arizona. En route to her base at Sunnyvale, California, she reached Camp Kearny, California, on the morning of 11 May, and attempted to moor. Since neither the trained ground handlers nor the specialized mooring equipment needed by an airship of Akron's size were present, the landing at Camp Kearny was fraught with danger. By the time she started the evaluation, the heat of the sun's rays had warmed her, and her engines had further lightened the airship by using 40 short tons (36 t) of fuel during her voyage across the continent. As a result, Akron became uncontrollable.

Her mooring cable cut to avert a catastrophic nose-stand by the errant airship, Akron headed up. Most men of the mooring crew, predominantly "boot" seamen from the Naval Training Station at San Diego, let go their lines. However, one man was carried 15 feet (4.6 m) into the air before he let go and suffered a broken arm in the process. Three others were carried up even farther. Two of these men — Aviation Carpenter's Mate 3d Class Robert H. Edsall and Apprentice Seaman Nigel M. Henton — lost their grips and fell to their deaths. The third, Apprentice Seaman C. M. "Bud" Cowart, clung desperately to his line and made himself fast to it before he was hoisted aboard Akron one hour later.[4] Nevertheless, Akron managed to moor at Camp Kearny later that day and proceeded thence to Sunnyvale. The tragic accident was captured on Newsreel film.

West coast flights

Over the weeks that followed, Akron "showed the flag" on the west coast, ranging as far north as the Canadian border before returning south in time to exercise once more with the Scouting Fleet. Serving as part of the "Green" Force, Akron attempted to locate the "White" Force. Although opposed by Vought O2U Corsair floatplanes from "enemy" ships, she managed to locate the opposing forces in just 22 hours — a fact not lost upon some of the participants in the exercise in subsequent critiques.

With Akron in need of repairs, she departed Sunnyvale on 11 June, bound for Lakehurst. The return trip was studded with difficulties, principally due to unfavorable weather. After a "long and sometimes harrowing" aerial voyage, she ultimately arrived on 15 June.

Akron underwent a period of voyage repairs upon her return from the west coast, and in July took part in a search for Curlew, a yacht which had failed to reach port at the end of a race to Bermuda. (The yacht was later discovered safe off Nantucket.)[5]. She then resumed operations with her "trapeze" and her planes. On 20 July, Admiral Moffett again embarked in Akron but the next day left the airship in one of her N2Y-1s which took him back to Lakehurst after a severe storm had delayed her own return to base.

Further tests as "flying aircraft carrier"

That summer, Akron entered a new phase of her career — one of intense experimentation with the revolutionary "trapeze" and a full complement of F9C-2s'. A key element of the entrance into that new phase was her new commanding officer, Commander Alger Dresel.

Another accident

Unfortunately, another accident hampered her vital training. On 22 August, Akron's fin fouled a hangar beam after a premature order to commence towing the ship out of the mooring circle. Nevertheless, rapid repairs enabled her to conduct eight flights over the Atlantic during the last three months of 1932. These operations involved intensive work with the trapeze and the F9C-2s, as well as the drilling of lookouts and gun crews.

Among the tasks undertaken was that involving the maintenance of two aircraft patrolling and scouting on Akron's flanks. During a seven-hour period on 18 November 1932, the airship and a trio of planes searched a sector 100 miles (160 km)[citation needed] wide.

Return to the fleet

After local operations out of Lakehurst for the remainder of 1932, Akron was ready to resume her work with the fleet. On the afternoon of 3 January 1933, Commander Frank C. McCord relieved Commander Dresel as commanding officer, the latter USS Macon's first captain. Within hours, Akron was on her way south, down the eastern seaboard and shaping a course toward Florida. She refueled at the Naval Reserve Aviation Base, Opa-locka, Florida, near Miami, on 4 January and then proceeded to Guantánamo Bay for an inspection of base sites. At this time, she used one of her N2Y-1s as an aerial "taxi" to ferry members of the inspection party back and forth.

Soon thereafter, Akron returned to Lakehurst for local operations which were interrupted by a two-week overhaul and poor weather. During March, the rigid airship carried out intensive training with her embarked aviation unit of F9C-2s, honing her hook-on skills. During the course of these operations, she cruised to Washington DC, and overflew the capital on 4 March 1933, the day Franklin D. Roosevelt took the oath of office as President of the United States.

On 11 March, Akron departed Lakehurst bound for Panama. She stopped briefly en route at Opa-Locka before proceeding on to Balboa. There an inspection party looked over a potential air base site. While returning northward the rigid airship paused at Opa-Locka for local operations exercising her gun crews with the N2Y-1s serving as targets for the gunners. Finally, on 22 March, she got underway to return to Lakehurst.

Wreck of Akron

On the evening of 3 April 1933, Akron cast off from her moorings to operate along the coast of New England, assisting in the calibration of radio direction finder stations, with Rear Admiral Moffett embarked. Also on board were: Commander Harry B. Cecil, the admiral's aide; Commander Fred T. Berry, commanding officer of NAS Lakehurst; and Lieutenant Colonel Alfred F. Masury, USAR (a guest of the admiral, vice-president of the Mack Truck Co., and strong proponent of the potential civilian uses of rigid airships).

As she proceeded on her way, Akron encountered severe weather, which did not improve as she passed over Barnegat Light, New Jersey, at 2200 (10:00 PM) on 3 April. Wind gusts of terrific force struck the airship unmercifully. Akron was being flown into an area of lower barometric pressure than at take-off; this caused the actual altitude flown to be lower than that indicated in the control gondola. Around 0030 (12:30 AM) on 4 April, Akron was caught by an updraft, then immediately by a downdraft. Her captain, Commander McCord, ordered full speed ahead, ballast dropped; the executive officer, Lt. Cdr. Herbert V. Wiley, was handling the ballast and emptied the bow emergency ballast. This, coupled with the elevator man holding nose up, caused the nose to rise. It also caused the tail to rotate down. Akron's descent was only temporarily halted, and downdrafts forced her down further. Wiley activated the 18 'howlers' of the ship's telephone system, a signal to landing stations. At this point the airship was nose up at between 12 and 25 degrees.

The Engineering Officer called out "800 feet" (240 m), which was followed by a 'gust' of intense violence. The steersman reported no response to his wheel. The lower rudder cables had been torn away. While the control gondola was still hundreds of feet high, the lower fin of Akron had struck the water and was torn off. ZRS-4 rapidly broke up and sank in the stormy Atlantic. Akron had been destroyed by operator error: it was flown into the sea while operating in an intense storm front. The German motorship Phoebus in the vicinity saw lights descending toward the ocean at about 0023 (12:23 AM) and altered course to starboard to investigate, thinking she was witnessing a plane crash. At 0055 (12:55 AM) on 4 April, Phoebus picked up Commander Wiley, unconscious, while the ship's boat picked up three more men: Chief Radioman Robert W. Copeland, Boatswain's Mate Second Class Richard E. Deal, and Aviation Metalsmith Second Class Moody E. Ervin. Despite desperate artificial respiration, Copeland never regained consciousness and died aboard Phoebus.

Although the German sailors spotted four or five other men in the stormy seas, they did not know their ship had chanced upon the crash of Akron until Lieutenant Commander Wiley regained consciousness half an hour after being rescued. Phoebus combed the ocean with her boats for over five hours in a dogged but fruitless search for more survivors. Navy blimp J-3, sent out to join the search, also crashed, with the loss of two men.{See [6]}

The United States Coast Guard cutter Tucker, the first American vessel on the scene, arrived at 0600 (6:00 AM) and took aboard Akron survivors and the body of Copeland, releasing Phoebus. Among the other ships which relentlessly combed the area for more survivors were the heavy cruiser Portland, the destroyer Cole, Coast Guard cutter Mojave, and the Coast Guard destroyers McDougal and Hunt, as well as two Coast Guard planes. Most of the casualties had been caused by drowning and hypothermia, as the crew had not been issued life jackets and there had not been time to deploy the single life raft. The crash left 73 dead, making it the deadliest air crash up to the time.

Aftermath of the wreck

Akron's loss spelled the beginning of the end for the rigid airship in the Navy, especially since one of its leading proponents, Rear Admiral Moffett, died in her, as did 72 other men. As President Roosevelt commented afterward: "The loss of the Akron with its crew of gallant officers and men is a national disaster. I grieve with the Nation and especially with the wives and families of the men who were lost. Ships can be replaced, but the Nation can ill afford to lose such men as Rear Admiral William A. Moffett and his shipmates who died with him upholding to the end the finest traditions of the United States Navy."

Macon and other airships received life jacket packs in order to avert a repetition of the tragedy.

Songwriter Bob Miller wrote and recorded a song, "The Crash of the Akron," within one day of the disaster.[7]

See also

- List of airships of the United States Navy

- USS Macon (ZRS-5) Akron's sister ship.

- List of airship accidents

References

- ^ Akron-Summit County Public Library, Summit Memory, Goodyear-Zeppelin Corporation, Facts About the World's Largest Airship Factory & Dock, retrieved 2008-11-15

{{citation}}: External link in|first= - ^ Summit Memory. U.S.S. Akron - Fuel. Retrieved 2008-07-22

- ^ Summit Memory. U.S.S. Akron - Propeller. Retrieved 2008-07-22

- ^ http://www.history.navy.mil/photos/ac-usn22/z-types/zrs4-k.htm

- ^ Cruise of the Curlew - TIME

- ^ [1]

- ^ "Newsweek: "Come All You True People, a Story to Hear"". Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- Robinson, Douglas H., and Charles L. Keller. "Up Ship!": U.S. Navy Rigid Airships 1919-1935. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 1982. ISBN 0-87021-738-0

- Richard K. Smith, The Airships Akron & Macon (Flying Aircraft Carriers of the United States Navy), United States Naval Institute: Annapolis, Maryland, 1965

- Department Of The Navy, Naval Historical Center. USS Akron. Retrieved 5 May 2005.

External links

- USS Akron page from the Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships

- USS Akron and Macon

- Images of the U.S.S. Akron from the Summit Memory Project

- the 3 survivors of the Akron

![]() This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

- United States Navy airships

- Airborne aircraft carriers

- Aircraft carriers of the United States

- Aviation accidents and incidents in the United States

- Aviation accidents and incidents in 1933

- United States Navy Ohio-related ships

- Disasters in New Jersey

- United States aircraft 1930-1939

- Filmed deaths from falls

- Ships built in Ohio