Yellow Sea

35°0′N 123°0′E / 35.000°N 123.000°E

| Yellow Sea | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 黄海 | ||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 黃海 | ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | yellow sea | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||

| Hangul | [[[wikt:황|황]]해 or 서해] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | ||||||||||||||

| Hanja | [[[wikt:黃|黃]]海 or 西海] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) | ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | yellow sea or west sea | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Yellow Sea | |

|---|---|

| River sources | Yellow River, Hai River, Yalu River, Taedong River, Han River |

| Basin countries | China North Korea South Korea |

| Surface area | 380,000 km2 (150,000 sq mi) |

| Average depth | Avg. 44 m (144 ft) Max. 152 m (499 ft) |

The Yellow Sea is the name given to the northern part of the East China Sea, which is a marginal sea of the Pacific Ocean. It is located between mainland China and the Korean Peninsula. Its name comes from the sand particles from Gobi Desert sand storms that turn the surface of the water golden yellow.

The innermost bay of the Yellow Sea is called the Bohai Sea (previously Pechihli Bay or Chihli Bay). Into it flow both the Yellow River (through Shandong province and its capital Jinan) and Hai He (through Beijing and Tianjin). Deposits of sand and silt from those rivers contribute to the sea colour.

The northern extension of the Yellow Sea is called the Korea Bay.

The Yellow Sea is one of four seas named after common colour terms — the others being the Black Sea, the Red Sea and the White Sea.

Geography

Extent

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the limits of the Yellow Sea (which it also names as "Hwang Hai") as follows:[1]

On the South. The parallel of 33°17' North from Saisyu To (Quelpart) [now known as Jeju-do] to the mainland [of China]. On the Southeast. From the Western extreme of Quelpart to Ka Nyo or West Pinnacle Island (34°13'N) in the Mengoru Group, thence to the North point of Oku To (34°22'N), to the West point of Small South Stone Island (Syo-Zyonan To) and the North point of Great South Stone Island (Zyonan To) (34°24'N) to a point on the coast of Tin To (34°25'N) along the Northwest coast of this island to the North point thereof, and thence on a line in a Northeasterly direction to the mainland of Tyosen (Korea).

Physiography

The Yellow Sea, excluding the Bohai, extends by about 960 km (600 mi) from north to south and about 700 km (430 mi) from east to west; it has an area of about 380,000 km2 (150,000 sq mi) and the volume of about 17,000 km3 (4,100 cu mi).[3] Its depth is only 44 m (144 ft) on average, with a maximum of 152 m (499 ft). The sea is a flooded section of continental shelf that formed after the last ice age (some 10,000 years ago) as sea levels rose 120 m (390 ft) to their current levels. The sea bottom is slowly rising toward China and more rapidly at the Korean Peninsula. The depth gradually increases from north to south.[3] The sea bottom and shores are dominated by sand and silt brought by the rivers through the Bohai Sea (Liao River, Yellow River, Hai He) and the Korea Bay (Yalu River). Those deposits, together with sand storms are responsible for the yellow water color and the sea name.[4]

Major islands of the sea include Anmado, Baengnyeongdo, Daebudo, Deokjeokdo, Gageodo, Ganghwado, Hauido, Heuksando, Hongdo, Jejudo, Jindo, Muuido, Sido, Silmido, Sindo, Wando, Yeongjongdo and Yeonpyeongdo (all in South Korea).

Climate and hydrology

The area has cold, dry winters with strong northerly monsoons blowing from late November to March. Average January temperatures are −10 °C (14 °F) in the north and 3 °C (37 °F) in the south. Summers are wet and warm with frequent typhoons between June and October.[3] Air temperatures range between 10 and 28 °C (50 and 82 °F). The average annual precipitation increases from about 500 mm (20 in) in the north to 1,000 mm (39 in) in the south. Fog is frequent along the coasts, especially in the upwelling cold-water areas.[4]

The sea has a warm cyclone current. It is a part of the Kuroshio Current, which diverges near the western part of Japan and flows northward into the Yellow Sea at the speed of below 0.8 km/h (0.50 mph). Southward currents prevail near the sea coast, especially in the winter monsoon period.[4]

The water temperature is close to freezing in the northern part in winter, so drift ice patches and continuous ice fields form and hinder navigation between November and March. The water temperature and salinity are homogeneous across the depth. The southern waters are warmer at 6–8 °C (43–46 °F). In spring and summer, the upper layer is warmed up by the sun and diluted by the fresh water from rivers, while the deeper water remains cold and saline. This deep water stagnates and slowly moves south. Commercial bottom-dwelling fishes are found around this mass of water, especially at its southern part. Summer temperatures range between 22 and 28 °C (72 and 82 °F). The average salinity is relatively low, at 30‰ in the north to 33–34‰ in the south, dropping to 26‰ or lower near the river deltas. In the southwest monsoon season (June to August) the increased rainfall and runoff further reduce the salinity of the upper sea layer.[4] Water transparency increases from about 10 meters (33 ft) in the north up to 45 meters (148 ft) in the south.[3]

Tides are semidiurnal, i.e. rise twice a day. Their amplitude varies between about 0.9 and 3 meters (3.0 and 9.8 ft) at the coast of China. Tides are higher at the Korean Peninsula, typically ranging between 4 and 8 meters (13 and 26 ft) and reaching the maximum in spring. The tidal system rotates in a counterclockwise direction. The speed of the tidal current is generally less than 1.6 km/h (0.99 mph) in the middle of the sea, but may increase to more than 5.6 km/h (3.5 mph) near the coasts.[4] The fastest tides reaching 20 km/h (12 mph) occur in the Myeongnyang Strait between the Jindo Island and the Korean Peninsula.[6]

The tide-related sea level variations result in a local phenomenon (a "Moses Miracle") when a land pass 2.9 km (1.8 mi) long and 10–40 meters (33–131 ft) wide opens for an hour between the Jindo and Modo islands. The event occurs approximately twice a year, at the beginning of May and in the middle of June. It had long been celebrated in a local festival called "Jindo Sea Parting Festival", but was largely unknown to the world until 1975, when the French ambassador Pierre Randi described the phenomenon in a French newspaper.[7][8][9]

Flora and fauna

The sea is rich in seaweed (predominantly kelp, Laminaria japonica), cephalopods, crustaceans, shellfishes, clams, and especially in blue-green algae which bloom in summer and contribute to the water color (see image above). For example, the seaweed production in the area was as high as 1.5 million tonnes in 1979 for China alone. The abundance of all those species increases toward the south and indicates high sea productivity that accounts for the large fish production in the sea.[11] Newer species of goby fish was also discovered.[12]

The southern part of the Yellow Sea, including the entire west coast of Korea, contains a 10 km-wide (6.2 mi) belt of intertidal mudflats, which has the total area of 2,850 km2 (1,100 sq mi) and is maintained by 4–10 m (13–33 ft). Those flats consist of highly productive sediments with a rich benthic fauna and are of great importance for migratory waders and shorebirds.[13] Surveys show that the area is the single most important site for migratory birds on northward migration in the entire East Asian – Australasian Flyway, with more than 35 species occurring in internationally significant numbers. Two million birds, at minimum, pass through at the time, and about half that number use it on southward migration.[14][15] About 300,000 migrating birds were transiting annually only through the Saemangeum tidal flat area. This estuary was however dammed by South Korea in 1991–2006 that resulted in drying off the land.[16] Land reclamation also took 65% of the intertidal area in China between the 1950s and 2002,[17] and there are plans to reclaim a further 45%.[18]

Oceanic megafaunas'bio-diversities, such as of marine mammals, sea turtles, and larger fish drastically decreased in modern time not only by pollutions but also mainly by direct hunting, most extensively Japanese industrial whaling,[19] illegal mass operations by Soviet with supports from Japan.[20] and fewer species survived to today although being still in serious perils. Those include spotted seals, and cetaceans such as minke whales, killer whales,[21] false killer whales, and finless porpoises, but nonetheless all the remnants of species listed could be in very small numbers. Historically, large whales were very abundant either for summering and wintering in the Yellow and Bohai Seas. For example, a unique population of resident fin whales and gray whales[22] were historically presented,[23] or possibly hosted some North Pacific right whales[24][25] and Humpback whales (3 whales including a cow calf pair was observed at Changhai County in 2015[26][27][28]) year-round other than migrating individuals, and many other migratory species such as Baird's beaked whales.[29] Even blue whales, Japanese sea lions, dugongs (in southern regions only),[30] and leatherback turtles used to breed or migrate into Yellow and Bohai seas.[31]

Spotted seals are only species thriving in today's Yellow sea and being the only resident species as well. A sanctuary for these seals is situated at Baengnyeongdo which is also known for local finless porpoises.[32] Great white sharks have been spotted to prey on seals in these areas as well.[33]

Economy

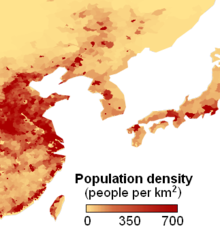

The coasts of the Yellow Sea are very densely populated, at approximately 250 inhabitants per square kilometer (650/sq mi).[34] The sea waters had been used for fishing by the Chinese, Korean and Japanese ships for centuries. Especially rich in fish are the bottom layers. About 200 fish species are exploited commercially, especially sea bream, croakers, lizard fishes, prawns, cutlassfish, horse mackerel, squid, eel, filefish, Pacific herring, chub mackerel and flounder.[35] The intensity of fishing has been gradually increasing for China and Korea and decreasing for Japan. For example, the production volumes for China rose from 619,000 tonnes in 1985 to 1,984,400 tonnes in 1996.[36] All species are overfished, however, and while the total catchments are rising, the fish population is continuously declining for most species.[4][37]

Navigation is another traditional activity in the Yellow Sea. The main Chinese ports are Dalian, Tianjin, Qingdao and Qinhuangdao. The major South Korean ports on the Yellow Sea are Incheon, Gunsan and Mokpo, and that for North Korea is Nampho, the outport of Pyongyang. The Bohai Train Ferry provides a shortcut between the Liaodong Peninsula and Shandong.[4] A major naval accident occurred on 24 November 1999 at Yantai, Shandong, China when the 9,000-ton Chinese ferry Dashun caught fire and capsized in rough seas. About 300 people were killed making it the worst maritime incident in China.[38]

Oil exploration has been successful in the Chinese and North Korean portions of the sea, with the proven and estimated reserves of about 9 and 20 billion tonnes, respectively.[39] However, the study and exploration of the sea is somewhat hindered by insufficient sharing of information between the involved countries. China initiated collaborations with foreign oil companies in 1979, but this initiative declined later.[4]

A major oil spill occurred on 16 July 2010 when a pipeline exploded at the north-east port of Dalian, causing a wide-scale fire and spreading about 1,500 tonnes of oil over the sea area of 430 km2 (170 sq mi). The port had been closed and fishing suspended until the end of August. Eight hundred fishing boats and 40 specialized vessels were mobilized to relieve the environmental damage.[40]

State of the environment

The Yellow Sea is considered among the most degraded marine areas on earth.[41] Loss of natural coastal habitats due to land reclamation has resulted in the destruction of more than 60% of tidal wetlands around the Yellow Sea coastline in approximately 50 years.[17] Rapid coastal development for agriculture, aquaculture and industrial development are considered the primary drivers of coastal destruction in the region.[17]

In addition to land reclamation, the Yellow Sea ecosystem is facing several other serious environmental problems. Pollution is widespread and deterioration of pelagic and benthic habitat quality has occurred, and harmful algal blooms frequently occur.[42] Invasion of introduced species are having a detrimental effect on the Yellow Sea environment. There are 25 intentionally introduced species and 9 unintentionally introduced species in the Yellow Sea Large Marine Ecosystem.[41] Declines of biodiversity, fisheries and ecosystem services in the Yellow Sea are widespread.[41]

See also

- Battle of Chemulpo Bay

- Battle of the Yellow Sea

- Geography of China

- Geography of North Korea

- Geography of South Korea

- Ganghwa Island incident

References

- ^ "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ^ Sand storm over Yellow Sea, nasa.gov

- ^ a b c d Yellow Sea, Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Yellow Sea, Encyclopædia Britannica on-line

- ^ Sediments and Phytoplankton bloom near the Mouth of the Yangtze, East China Sea, NASA, 2002

- ^ M. J. King, et al. Twinning of Jindo Grand Bridge, Republic of Korea in Current and future trends in bridge design, construction and maintenance 2: safety, economy, sustainability and aesthetics; proceedings of the international conference organized by the Institution of Civil Engineers and held in Hong Kong on 25–26 April 2001 ISBN 0-7277-3091-6 pp. 175, 177

- ^ The Moses Miracle Of Jindo Island, 17 July 2010

- ^ Майские фестивали в Чолладо – от "чуда Моисея" до боя быков (in Russian)

- ^ Jindo Mysterious Sea Road, Jindo County

- ^ Bar-tailed Godwit Updates, USGS

- ^ Chikuni, pp. 8, 16, 19

- ^ http://www.esa.int/Our_Activities/Observing_the_Earth/Earth_from_Space_The_Yellow_Sea_of_China

- ^ Maurice L. Schwartz (2005) Encyclopedia of coastal science, ISBN 1-4020-1903-3 p.60

- ^ Barter, M.A. (2002). Shorebirds of the Yellow Sea – importance, threats and conservation status. Wetlands International Global Series Vol. 9. International Wader Studies Vol. 12. Canberra ISBN 90-5882-009-2

- ^ Barter, M.A. (2005). Yellow Sea – driven priorities for Australian shorebird researchers. pp. 158–160 in: "Status and Conservation of Shorebirds in the East Asian – Australasian Flyway". Proceedings of the Australasian Shorebird Conference, 13–15 December 2003, Canberra, Australia. International Wader Studies 17. Sydney.

- ^ Saemangeum and the Saemangeum Shorebird Monitoring Program (SSMP) 2006–2008, Birds Korea

- ^ a b c Murray N. J., Clemens R. S., Phinn S. R., Possingham H. P. & Fuller R. A. (2014) Tracking the rapid loss of tidal wetlands in the Yellow Sea. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 12, 267-72. doi:10.1890/130260

- ^ David Lindenmayer, Mark Burgman, Mark A. Burgman (2005) Practical conservation biology, ISBN 0-643-09089-4 p. 172

- ^ Weller, D.; et al. (2002). "The western gray whale: a review of past exploitation, current status and potential threats". 4 (1). J. Cetacean Res. Manage: 7–12. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Berzin A.,Ivashchenko V.Y., Clapham J.P.,Brownell L. R.Jr. (2008). "The Truth About Soviet Whaling: A Memoir" (PDF). DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://ocean.kisti.re.kr/downfile/volume/kofis/KSSHBC/2012/v45n5/KSSHBC_2012_v45n5_486.pdf

- ^ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275960466_A_Gray_Area_On_the_Matter_of_Gray_Whales_in_the_Western_North_Pacific

- ^ MIZROCH A.S.. RICE W.D.. ZWIEFELHOFER D.. WAITE J.. PERRYMAN L.W.. 2009. Distribution and movements of fin whales in the North Pacific Ocean. on The Wiley Online Library. Retrieved on 3 January. 2015

- ^ http://chuansong.me/n/2457684

- ^ A spatially explicit estimate of the prewhaling abundance of the endangered North Atlantic right whale

- ^ 长海又现鲸鱼 这回是好几条

- ^ 长海又现鲸鱼 这回是好几条

- ^ 大连长海又见鲸鱼一家亲!三条!四条

- ^ "A Baird's Beaked Whale From the East China Sea". FISHERIES SCIENCE, 1998-05. Zhe Jiang Museum of Natural History. 1998. p. CNKI – The China National Knowledge Infrastructure. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ http://wwf.panda.org/about_our_earth/ecoregions/yellow_sea.cfm

- ^ Mr.Z. Charlie. 2008. 我国的渤海里有没有鲸鱼 on Sogou - Wenwen. Retrieved on 3 January. 2015

- ^ 백령도 어부들의 친구 쇠돌고래

- ^ 백상아리, 백령도서 물범 공격장면 국내 첫 포착

- ^ a b Population Density, NASA, 1994

- ^ Chikuni, p. 25

- ^ Fishing Industry, noaa.gov

- ^ Chikuni, pp. 37, 47, 55

- ^ Ferry sinks in Yellow Sea, killing hundreds, 24 November 1999

- ^ China found new large oil field in the Yellow Sea, News.ru, 3 May 2007 (in Russian)

- ^ China's worst-ever oil spill threatens wildlife as volunteers assist in clean-up, Guardian, 21 July 2010

- ^ a b c UNDP/GEF. (2007) The Yellow Sea: Analysis of Environmental Status and Trends. p. 408, Ansan, Republic of Korea.

- ^ "China's largest algal bloom turns the Yellow Sea green". The Guardian.

Bibliography

- Chikuni, S. (1985) The fish resources of the northwest Pacific, Food and Agriculture Organization, ISBN 92-5-102298-4