Yolngu

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Australia | |

| Languages | |

| Yolŋu Matha (Dhaŋu-Djaŋu, Nhaŋu, Dhuwal, Ritharŋu, Djinaŋ, Djinba), Australian English, Yolngu Sign Language | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional religions, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Australian Aboriginals |

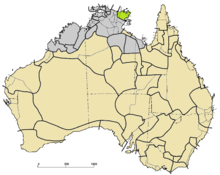

The Yolngu or Yolŋu (IPA: [ˈjuːlŋʊ]) are an aggregation of indigenous Australian people inhabiting north-eastern Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory of Australia. Yolngu means "person" in the Yolŋu languages. The terms Murngin and Wulamba were formerly used by some anthropologists for the Yolngu.[1][2] All Yolngu clans are affiliated with either the Dhuwa (Dua) or the Yirritja moiety.

Name

The ethnonym Murrgin gained currency after its extensive use in a book by the American anthropologist W. Lloyd Warner,[3] whose study of the Yolngu, A Black Civilization: a Social Study of an Australian Tribe (1937) quickly assumed the status of an ethnographical classic, considered by R. Lauriston Sharp the "first adequately rounded out descriptive picture of an Australian aboriginal community."[4] Norman Tindale was dismissive of the term, regarding it, like the term Kurnai, as "artificial", having been arbitrarily applied to a large number of peoples of northeastern Australia. The proper transliteration of the word was, in any case, Muraŋin, meaning "shovel-nosed spear folk", an expression appropriate to western[5] peripheral tribes, such as the Rembarrnga of the general area Warner described.[a] For Tindale, following recent linguistic studies, the eastern Arnhem Land tribes constituting the Yolgnu lacked the standard tribal structures evidenced elsewhere in aboriginal Australia, in comprising several distinct socio-linguistic realities in an otherwise integral cultural continuum.[7] He classified these as the Yan-nhaŋu, Djinang, Djinba, Djaŋu, Dangu, Rembarrnga, Ritharngu, Dhuwal and the Dhuwala.

Warner had deployed the term "Murngin" to denote a group of peoples who shared, in his analysis, a distinctive form of kinship organisation, describing their marriage rules, subsection system and kinship terminology. Other researchers in the field quickly contested his early findings. T. Theodor Webb argued that Warner's Murngin actually referred to one moiety, and could only denote a Yiritcha mala, and dismissed Warner's terminology as misleading.[8] A. P. Elkin, comparing the work of Warner and Webb, endorsed the latter's analysis as more congruent with the known facts.[9]

People

Yolngu comprise several distinct groups, differentiated by the languages and dialects they speak, but generally sharing overall similarities in the ritual life and hunter-gathering economic and cultural lifestyles in the territory of eastern Arnhem land. Early ethnographers studying the Yolngu applied the nineteenth-century concepts of tribe, horde and phratry to classify and sort into separate identities the units forming the Yolngu ethnocultural mosaic. After the work of Ian Keen in particular, such taxonomic terminology is increasingly seen as problematical, and inadequate because of its eurocentric assumptions.[10] Specialists are undecided, for example, whether the languages spoken by the Yolngu amount to five or eight, and one survey arrived at eleven distinct "dialect" groups.[11]

Language

Yolŋu speak a dozen languages classified under the general heading of Yolngu Matha. English can be anywhere from a third to a tenth language for Yolŋu.

Kinship system

Yolŋu groups are connected by a complex kinship system (gurruṯu). This system governs fundamental aspects of Yolŋu life, including responsibilities for ceremony and marriage rules. People are introduced to children in terms of their relation to the child ("grandmother", "uncle", etc), introducing the child to kinship from the beginning.[12]

Yolŋu societies are generally[b] described in terms of a division of two exogamous patrimoieties: Dhuwa and Yirritja. Each of these is represented by people of a number of different groups, each of which have their own lands, languages, totems and philosophies.[14]

| Moiety | Clan groups |

|---|---|

| Yirritja | Gumatj, Gupapuyŋu, Waŋurri, Ritharrngu, Maŋalili, Munyuku, Maḏarrpa,

Warramiri, Dhalwaŋu, Liyalanmirri, Mäḻarra, Gamalaŋa, Gorryindi. |

| Dhuwa | Rirratjiŋu, Gälpu, Golumala, Marrakulu, Marraŋu, Djapu, Ḏatiwuy,

Ŋaymil, Djarrwark, Djambarrpuyŋu. |

A Yirritja person must always marry a Dhuwa person (and vice versa). Children take their father's moiety, meaning that if a man or woman is Dhuwa, their mother will be Yirritja (and vice versa).[12]

Kinship relations are also mapped onto the lands owned by the Yolŋu through their hereditary estates – so almost everything is either Yirritja or Dhuwa – every fish, stone, river, etc., belongs to one or the other moiety. For example, Yirritja yiḏaki (didgeridoos) are shorter and higher-pitched than Dhuwa yiḏaki.[15] A few items are wakinŋu (without moiety).

The term yothu-yindi (after which the band takes its name) literally means child-big (one), and describes the special relationship between a person and their mother's moiety (the opposite to their own).[12] Because of yothu-yindi, Yirritja have a special interest in and duty towards Dhuwa (and vice versa). For example, a Gumatj man may craft the varieties of yiḏaki associated with his own (Yirritja) clan group and the varieties associated with his mother's (Dhuwa) clan group.[16]

The word for "selfish" or "self-centred" in the Yolŋu languages is gurrutumiriw, literally "kin lacking" or "acting as if one has no kin".[12]

The moiety-based kinship of the Yolngu does not map in a straightforward way to the notion of the nuclear family, which makes accurate standardised reporting of households and relationships difficult, for example in the census.[12] Polygamy is a normal part of Yolngu life: one man was known to have 29 wives, a record exceed only by polygamous arrangements among the Tiwi.[17]

Avoidance relationships

As with nearly all Aboriginal groups, avoidance relationships exist in Yolngu culture between certain relations. The two main avoidance relationships are:

- son-in-law – mother-in-law

- brother – sister

Brother–sister avoidance, called mirriri, normally begins after initiation. In avoidance relationships, people do not speak directly or look at one another, and try to avoid being in too close proximity with each other. People are avoided, but respected.[citation needed]

Yolŋu law

The word for "law" in Yolgnu is rom.[18] The complete system of Yolngu customary law is known as Ngarra,[19] or as the Maḏayin.[20] Maḏayin embodies the rights of the owners of the law, or citizens (rom watangu walal) who have the rights and responsibilities for this embodiment of law. Maḏayin includes all the people's law (rom); the instruments and objects that encode and symbolise the law (Maḏayin girri); oral dictates; names and song cycles; and the holy, restricted places (dhuyu ṉuŋgat wäŋa) that are used in the maintenance, education and development of law.

This law covers the ownership of land and waters, the resources on or within these lands and waters.[21] It regulates and controls production and trade and the moral, social and religious law including laws for the conservation and the farming of plants and aquatic life.

Yolŋu believe that living out their life according to Maḏayin is right and civilised. The Maḏayin creates a state of Magaya, which is a state of peace, freedom from hostilities and true justice for all.[22]

Yolŋu seasons

Yolŋu identify six distinct seasons: Miḏawarr, Dharratharramirri, Rärranhdharr, Bärra'mirri, Dhuluḏur, Mayaltha and Guṉmul.[citation needed]

History

Macassan contact

Yolŋu engaged in extensive trade annually with Macassan fishermen at least two centuries before contact with Europeans. They made yearly visits to harvest trepang and pearls, paying Yolŋu in kind with goods such as knives, metal, canoes, tobacco and pipes. In 1906, the South Australian Government did not renew the Macassans' permit to harvest trepang, and the disruption caused economic losses for the regional Yolŋu economy.[citation needed]

Yolŋu oral histories and the Djanggawul myths preserve accounts of a Baijini people, who are said to have preceded the Macassans. These Baijini have been variously interpreted by modern researchers as a different group of (presumably, Southeast Asian) visitors to Australia who may have visited Arnhem Land before the Macassans,[23] as a mythological reflection of the experiences of some Yolŋu people who have travelled to Sulawesi with the Macassans and came back,[24] or perhaps as traders from China.[25]

Yolŋu also had well-established trade routes within Australia, extending to Central Australian clans and other Aboriginal countries. They did not manufacture boomerangs themselves but obtained these via trade from Central Australia.[26] This contact was maintained through use of message sticks, as well as mailmen – with some men walking several hundred kilometres in their work to send messages and relay orders between tribes.[citation needed]

European contact

Yolŋu had known about Europeans before the arrival of British in Australia through their contact with Macassan traders, which probably began around the sixteenth century. Their word for European, Balanda, is derived from "Hollander" (Dutch person).

Nineteenth century

In 1883, the explorer David Lindsay was the first colonial white to penetrate Yolgnu lands for the purposes of making a survey of its resources and prospects. He trekked along the Goyder River to reach the Arafura Swamp on the western fringe of Wagilak land.[27] Two years later the first colonial initiative to try and open up Arnhem Land for cattle grazing began, when herds driven over from Queensland were pastured around Florida Station. A violent series of battles ensued, resulting in a severe depopulation of Yolgnu in this south-western area of their territory, but the stiffness of resistance virtually ended efforts by the intruding balanda to take over further territory, and efforts at settlement ground to a halt.[28]

Twentieth century

In the early 20th century, Yolgnu oral history relates, punitive expeditions were launched into their territories.[29] The first mission to Yolngu country was set up at Milingimbi Island in 1922. The island is the traditional home of the Yan-nhaŋu. Beginning in 1932, over two years, three incidents of killing outsiders caused problems for the Yolgnu.

In 1932 some Japanese trepangers were speared by Yolŋu men, in what became known as the Caledon Bay crisis, after their mothers had been allegedly raped by some Japanese men.[citation needed] Two whites, Fagan and Traynor, were killed near Woodah Island the following year, and soon afterwards Constable McColl was speared on that island. Only the intervention of missionaries, who had a foothold on the fringes of this area, and of the anthropologist Donald Thomson, averted an official reprisal designed to "teach the wild blacks a lesson."[29] Several Yolŋu were imprisoned in Fannie Bay Gaol in present-day Darwin. However, Thomson was able to help to have them released by going to live with the Yolŋu and ascertaining the facts of the case.[citation needed]

Thomson lived with the Yolŋu for several years and made some photographic and written records of their way of life at that time. These have become important historical documents for both Yolŋu and European Australians.{{cn}

In 1935 a Methodist mission opened in Arnhem Land.

In 1941, during World War II, Thomson persuaded the Australian Army to establish a Special Reconnaissance Unit (NTSRU) of Yolŋu men to help repel Japanese raids on Australia's northern coastline (classified as top secret at the time). Yolŋu made contact with Australian and US servicemen, although Thomson was keen to prevent this. (It is believed this is where petrol sniffing began for Aboriginal Australians[citation needed]). Thomson relates how the soldiers would often try to obtain Yolŋu spears as mementos. These spears were vital to Yolŋu livelihood, and took several days to make and forge.

More recently, Yolngu have seen the imposition of large mines on their tribal lands at Nhulunbuy.[citation needed]

Yolngu in politics

Since the 1960s Yolngu leaders have been conspicuous in the struggle for Aboriginal land rights.

In 1963, provoked by a unilateral government decision to excise a part of their land for a bauxite mine, Yolngu at Yirrkala sent to the Australian House of Representatives a petition on bark. The bark petition attracted national and international attention and now hangs in Parliament House, Canberra as a testament to the Yolngu role in the birth of the land rights movement.

When the politicians demonstrated they would not change their minds, the Yolngu of Yirrkala took their grievances to the courts in 1971, in the case of Milirrpum v Nabalco Pty Ltd, the Gove land rights case. Yolngu lost the case because Australian courts were still bound to follow the terra nullius principle, which did not allow for the recognition of any "prior rights" to land to Indigenous people at the time of colonisation. However, the Judge did acknowledge the claimants' ritual and economic use of the land and that they had an established system of law, paving the way for future Aboriginal Land Rights in Australia.

The song "Treaty", by Yothu Yindi, which became an international hit in 1989, arose as a remonstration over the tardiness of the Hawke government in enacting promises to deal with Aboriginal land rights, and made a powerful pleas for respect for Yolngu culture, territory and Law.[30]

Yolngu arts

Yolngu artists and performers have been at the forefront of global recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture. Yolngu traditional dancers and musicians have performed widely throughout the world and retain a germinal influence, through the patronage of the Munyarryun and Marika families in particular, on contemporary performance troupes such as Bangarra Dance Theatre.[31]

Yolngu visual art

Before the emergence of the Western Desert art movement, the most well-known Aboriginal art was the Yolngu style of fine cross-hatching paintings on bark. The hollow logs (larrakitj) used in Arnhem Land burial practices serve an important spiritual purpose and are also important canvases for Yolngu art. David Malangi Daymirringu's bark depiction of Manharrnju clan mourning rites of the clan, from a private collection, was copied and featured on the original Australian one-dollar note. When the copyright violation came to light the Australian government, through the direct agency of H. C. Coombs, hastened to remunerate the artist.[32]

Yolngu are also weavers. They weave dyed pandanus leaves into baskets. Necklaces are also made from beads made of seeds, fish vertebrae or shells. Colours are often important in determining where artwork comes from and which clan or family group created it. Some designs are the insignia of particular families and clans.

Yolngu music

The Yothu Yindi band, especially after its song "Treaty", performed the most popular indigenous music since Jimmy Little's Royal Telephone (1963) became Australia's most successful contemporary indigenous music group, and performed throughout the world. Their work has elicited serious musicological analysis.[33]

Arnhem Land is the home of the yiḏaki, which Europeans have named the didgeridoo. Yolngu are both players and craftsmen of the yiḏaki. It can only be played by certain men, and traditionally there are strict protocols around its use.[clarification needed]

Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu (1971–2017) was a famous Yolngu singer.

Prominent Yolngu

- Baker Boy (Danzal Baker)

- Laurie Baymarrwangga

- George Rrurrambu Burarrwanga

- Gary Dhurrkay

- Gatjil Djerrkura

- Nathan Djerrkura

- David Gulpilil

- Djalu Gurruwiwi

- Leila Gurruwiwi

- Rarriwuy Hick

- David Malangi

- Janet Munyarryun

- Galarrwuy Yunupingu

- Geoffrey Gurrumul Yunupingu

- Mandawuy Yunupingu

Politicians

- Yingiya Mark Guyula, Independent member for Nhulunbuy in the Northern Territory Legislative Assembly.

Films about Yolngu

The Magic Pill

Garma festival

Every year, Yolngu come together to celebrate their culture at the Garma Festival of Traditional Cultures. Non-Yolngu are welcome to attend the festival and learn about Yolngu traditions and Law. The Yothu Yindi Foundation oversees this festival.

Yolngu ethnographic studies

A Deakin University study investigated Aboriginal knowledge systems in reaction to what the authors regarded as Western ethnocentrism in science studies. They argue that Yolngu culture is a system of knowledge different in many ways from that of Western culture, and may be broadly described as viewing the world as a related whole rather than as a collection of objects. Singing the Land, Signing the Land, by Watson and Chambers, explores the relationship between Yolngu and Western knowledge by using the Yolngu idea of ganma, which metaphorically describes two streams, one coming from the land (Yolngu knowledge) and one from the sea (Western knowledge) engulfing each other so that "the forces of the streams combine and lead to deeper understanding and truth."

See also

- Gove land rights case

- Indigenous Australian food groups

- Yirrkala bark petitions

- Taboo against naming the dead

- Australian Aboriginal Astronomy

Notes

- ^ The word, used as an exonym by other tribes, referred to Arnhem Land tribes that had a reputation for aggressive behavior because they had managed to manufacture iron-bladed spears from metal cut from abandoned Caledon Bay water tanks.[6]

- ^ There are complications in the schematic models often adopted in ethnography to analyse kinship. The reader may consult two papers by Ian Keen for details.[10][13]

Citations

- ^ Keen 2005, p. 80.

- ^ N230 Yolngu Matha at the Australian Indigenous Languages Database, Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

- ^ Tindale 1974, p. 141.

- ^ Sharp 1939, p. 150.

- ^ Tindale 1974, p. 224.

- ^ Tindale 1974, pp. 141–142.

- ^ Tindale 1974, p. 141,157.

- ^ Webb 1933, p. 410 ?

- ^ Elkin 1933, pp. 415–416 ?

- ^ a b Keen 1995, pp. 502–527.

- ^ Bauer 2014, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b c d e Morphy 2008c.

- ^ Keen 2000, pp. 419–436.

- ^ Morphy 2008b, pp. 1–13.

- ^ Dhuwa and Yirritja Yiḏaki.

- ^ Yothu-Yindi and Yiḏaki Crafting.

- ^ Keen 1982, p. 620.

- ^ Christie 2007, p. 157,n.1.

- ^ Gaymarani 2011, p. 285.

- ^ Kelly 2014, p. 33.

- ^ Gaymarani 2011, pp. 286–287.

- ^ Williams 1986, pp. ?.

- ^ Berndt 2005, p. 55.

- ^ Swain 1993, p. 170.

- ^ Needham, Wang & Lu 1971, p. 538.

- ^ Thomson & Peterson 2005, p. ?.

- ^ White 2016, p. 323.

- ^ Morphy 2008a, p. 117.

- ^ a b Morphy 2008a, p. 118.

- ^ Corn 2009, p. 42.

- ^ Verghis 2014.

- ^ Evans 2016.

- ^ Stubington & Dunbar-Hall 1994, pp. 243–259.

Sources

- Bauer, Anastasia (2014). The Use of Signing Space in a Shared Sign Language of Australia. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-1-614-51547-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Berndt, Ronald M. (2005) [First published 1952]. Djanggawul: An Aboriginal Religious Cult of North-Eastern Arnhem Land. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415330220.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Christie, Michael (2007). "Ecological community and species attributes in Yolnghu religious symbolism". In Leitner, Gerhard; Malcolm, Ian G. (eds.). The Habitat of Australia's Aboriginal Languages: Past, Present and Future. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 57–78. ISBN 978-3-110-19079-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Corn, Aaron David Samuel (2009). Reflections & Voices: Exploring the Music of Yothu Yindi with Mandawuy Yunupingu. Sydney University Press. ISBN 978-1-920-89934-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Dhuwa and Yirritja Yiḏaki". YidakiStory.com. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- Evans, Brett (21 February 2016). "How Aboriginal artist Dave Malangi's design ended up on Australia's money". The Sydney Morning Herald.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Gaymarani, George Pascoe (2011). "An introduction to the Ngarra law of Arnhem Land". Northern Territory Law Journal. 1: 283–304.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Keen, Ian (December 1982). "How Some Murngin Men Marry Ten Wives: The Marital Implications of Matrilateral Cross-Cousin Structures". Man. New Series. 17 (4): 620–642. JSTOR 2802037.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Keen, Ian (August 1995). "Metaphor and the Metalanguage: "Groups" in Northeast Arnhem Land". American Ethnologist. 22 (3): 502–527. doi:10.1525/ae.1995.22.3.02a00030. JSTOR 645969.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Keen, Ian (September 2000). "A Bundle of Sticks: The Debate over Yolngu Clans". The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 6 (3): 419–436. JSTOR 2661083.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Keen, Ian (2005) [First published 1990]. "Ecological community and species attributes in Yolnghu religious symbolism". In Willis, Roy (ed.). Signifying Animals: Human Meaning in the Natural World. Routledge. pp. 80–96. ISBN 978-0-203-26481-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kelly, Danial (2014). "Foundational sources and purposes of authority in Madayin" (PDF). Victoria University Law and Justice Journal. 4 (1): 33–45. doi:10.15209/vulj.v4i1.40.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McIntosh, Ian S. (2008). "Missing the Revolution! Negotiating disclosure on the pre-Macassans (Bayini) in North-East Arnhem Land". In Thomas, Martin; Neale, Margo (eds.). Exploring the Legacy of the 1948 Arnhem Land Expedition. Australian National University. pp. ?.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Morphy, Frances (2008c). Invisible to the state: kinship and the Yolngu moral order. Negotiating the Sacred V: Governing the Family. Monash University.

{{cite conference}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Morphy, Frances (2008a). "Whose governance, for whose good? the Laynhapuy Homelands Associationand the neo-assimilationist turn in Indigenous policy". In Hunt, Janet; Smith, Diane; Garling, Stephanie; Sanders, Will (eds.). Contested Governance: Culture, power and institutions in Indigenous Australia. Vol. Volume 29. Australian National University Press. pp. 113–151. ISBN 978-1-876-94488-9. JSTOR j.ctt24hcb3.13.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Morphy, Frances (14–15 August 2008b). Invisible to the state: kinship and the Yolngu moral order (PDF). Negotiating the Sacred V: Governing the Family, Monash University. Monash University. pp. 1–13.

{{cite conference}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Needham, Joseph; Wang, Ling; Lu, Gwei-djen (1971). Physics and Physical Technology: Civil Engineering and Nautics. Science and Civilisation in China. Vol. 4:3. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0 521 07060 0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sharp, R. Lauriston (1939). "Review: W. Lloyd Warner, a Black Civilization: a Social Study of an Australian Tribe". American Anthropologist. 41 (1): 150–152. doi:10.1525/aa.1939.41.1.02a00250.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stubington, Jill; Dunbar-Hall, Peter (October 1994). "Yothu Yindi's 'Treaty': Ganma in Music". Popular Music. 13 (3): 243–259. doi:10.1017/s0261143000007182. JSTOR 852915.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Swain, Tony (1993). A place for strangers: towards a history of Australian Aboriginal being. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44691-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thomson, Donald; Peterson, Nicholas (2005). Donald Thomson in Arnhem Land. Miegunyah Press. ISBN 978-0-522-85205-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tindale, Norman Barnett (1974). "Murngin (NT)". Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits, and Proper Names. Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-708-10741-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Verghis, Sharon (7 June 2014). "Bangarra Dance Theatre: history in movement". The Australian.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Warner, William Lloyd (April 1930). "Morphology and Functions of the Australian Murngin Type of Kinship". American Anthropologist. 32 (2): 207–256. doi:10.1525/aa.1930.32.2.02a00010. JSTOR 661305.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Warner, William Lloyd (April–June 1931). "Morphology and Functions of the Australian Murngin Type of Kinship (Part II)". American Anthropologist. 33 (2): 172–198. doi:10.1525/aa.1931.33.2.02a00030. JSTOR 660835.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - White, Neville (2016). "A history of Donydji outstation, north-east Arnhem Land" (PDF). In Peterson, Nicolas; Myers, Fred (eds.). Experiments in self-determination: Histories of the outstation movement in Australia. Australian National University Press. pp. 323–346. ISBN 978-1-925-02289-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Williams, Nancy M. (1986). The Yolngu and Their Land: A System of Land Tenure and the Fight for Its Recognition. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-804-71306-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Yothu-Yindi and Yiḏaki Crafting". YidakiStory.com. Retrieved 29 July 2018.