Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor: Difference between revisions

→Political legacy: Mechelen |

→Reign in Burgundy and the Netherlands: Guelders, Max's son Philip the Fair |

||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

The Guinegate victory made Maximilian popular, but as an inexperienced ruler, he hurt himself politically by trying to centralize authority without respecting traditional rights and consulting relevant political bodies. The Belgian historian Eugène Duchesne comments that these years were among the saddest and most turbulent in the history of the country, and despite his later great imperial career, Maximilian unfortunately could never compensate for the mistakes he made as regent in this period. <ref>{{cite book |last1=Académie royale des sciences, des lettres et des beaux-arts de Belgique |title=Biographie nationale, Volume 14 |date=1897 |publisher=H. Thiry-Van Buggenhoudt |page=161 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fu0bAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA161 |access-date=24 October 2021}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Morren |first1=Paul |title=Van Karel de Stoute tot Karel V (1477-1519 |date=2004 |publisher=Garant |isbn=9789044115451 |page=66 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CMxU68_9lJoC&pg=PA57 |access-date=24 October 2021}}</ref> Some of the Netherlander provinces were hostile to Maximilian, and, in 1482, they signed [[Treaty of Arras (1482)|a treaty]] with Louis XI in [[Arras]] that forced Maximilian to give up [[Franche-Comté]] and [[Artois]] to the French crown.<ref name="WB1976" /> They [[Flemish revolts against Maximilian of Austria|openly rebelled]] twice in the period 1482–1492, attempting to regain the [[Great Privilege|autonomy]] they had enjoyed under Mary. Flemish rebels managed to capture Philip and even Maximilian himself, but they released Maximilian when Frederick III intervened.<ref name="vanleeuwen">{{Cite encyclopedia |year=2006 |title=Balancing Tradition and Rites of Rebellion: The Ritual Transfer of Power in Bruges on 12 February 1488 |encyclopedia=Symbolic Communication in Late Medieval Towns |publisher=Leuven University Press |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SEhNBaRxXWAC&pg=PA65 |author=Jacoba Van Leeuwen|isbn=9789058675224 }}</ref><ref name="buylaert">{{Cite journal |last1=Frederik Buylaert |last2=Jan Van Camp |last3=Bert Verwerft |year=2011 |editor2-last=Adrian R. Bell |title=Urban militias, nobles and mercenaries. The organization of the Antwerp army in the Flemish-Brabantine revolt of the 1480s |journal=Journal of Medieval Military History |volume=IX |editor1=Anne Curry}}</ref> In 1489, as he turned his attention to his hereditary lands, he left the Low Countries in the hands of [[Albert III, Duke of Saxony|Albert of Saxony]], who proved to be an excellent choice, as he was less emotionally committed to the Low Countries and more flexible as a politician than Maximilian, while also being a capable general. <ref>{{cite book |last1=Koenigsberger |first1=H. G. |title=Monarchies, States Generals and Parliaments: The Netherlands in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries |date=22 November 2001 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-80330-4 |page=87 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2V1dbsvEWnkC&pg=PA67 |access-date=26 October 2021 |language=en}}</ref> By 1492, rebellions were completely suppressed. Maximilian revoked the Great Privilege and established a strong ducal monarchy undisturbed by particularism. But he would not reintroduce Charles the Bold's centralizing ordinances. Since 1489 (after his departure), the government under Albert of Saxony had made more efforts in consulting representative institutions and showed more restraint in subjugating recalcitrant territories. Notables who had previously supported rebellions returned to city administrations. The Estates General continued to develop as a regular meeting place of the central government.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Tracy |first1=James D. |title=Emperor Charles V, Impresario of War: Campaign Strategy, International Finance, and Domestic Politics |date=14 November 2002 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-81431-7 |page=71 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tXKMvr09dB4C&pg=PA71 |access-date=26 October 2021 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Blockmans |first1=Willem Pieter |last2=Blockmans |first2=Wim |last3=Prevenier |first3=Walter |title=The Promised Lands: The Low Countries Under Burgundian Rule, 1369-1530 |date=1999 |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press |isbn=978-0-8122-1382-9 |page=207 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uj9nGDCiW64C&pg=PA207 |access-date=26 October 2021 |language=en}}</ref> The harsh suppression of the rebellions did have an unifying effect, in that provinces stopped behaving like separate entities each supporting a different lord.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Ellis |first1=Edward Sylvester |last2=Horne |first2=Charles Francis |title=The Story of the Greatest Nations: A Comprehensive History, Extending from the Earliest Times to the Present, Founded on the Most Modern Authorities, and Including Chronological Summaries and Pronouncing Vocabularies for Each Nation; and the World's Famous Events, Told in a Series of Brief Sketches Forming a Single Continuous Story of History and Illumined by a Complete Series of Notable Illustrations from the Great Historic Paintings of All Lands |date=1914 |publisher=Niglutsch |page=1904 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=y8RLAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA1857 |access-date=26 October 2021 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Gunn |first1=Steven |last2=Grummitt |first2=David |last3=Cools |first3=Hans |title=War, State, and Society in England and the Netherlands 1477-1559 |date=15 November 2007 |publisher=OUP Oxford |isbn=978-0-19-920750-3 |page=12 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QDpnAAAAMAAJ |access-date=26 October 2021 |language=en}}</ref> [[Helmut Koenigsberger]] opines that it was not the erratic leadership of Maximilian, who was brave but hardly understood the Netherlands, but the Estates' desire for the survival of the country that made the Burgundian monarchy survive.{{sfn|Koenigsberger|2021|p=70}} Bart van Loo agrees that his aristocratic upbringing and his militaristic tendencies did prevent him from understanding his subjects, leading to years of bloodbath, but his military leadership did save the country from France.{{sfn|Van Loo|2021|pp=558,565,567}} |

The Guinegate victory made Maximilian popular, but as an inexperienced ruler, he hurt himself politically by trying to centralize authority without respecting traditional rights and consulting relevant political bodies. The Belgian historian Eugène Duchesne comments that these years were among the saddest and most turbulent in the history of the country, and despite his later great imperial career, Maximilian unfortunately could never compensate for the mistakes he made as regent in this period. <ref>{{cite book |last1=Académie royale des sciences, des lettres et des beaux-arts de Belgique |title=Biographie nationale, Volume 14 |date=1897 |publisher=H. Thiry-Van Buggenhoudt |page=161 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fu0bAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA161 |access-date=24 October 2021}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Morren |first1=Paul |title=Van Karel de Stoute tot Karel V (1477-1519 |date=2004 |publisher=Garant |isbn=9789044115451 |page=66 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CMxU68_9lJoC&pg=PA57 |access-date=24 October 2021}}</ref> Some of the Netherlander provinces were hostile to Maximilian, and, in 1482, they signed [[Treaty of Arras (1482)|a treaty]] with Louis XI in [[Arras]] that forced Maximilian to give up [[Franche-Comté]] and [[Artois]] to the French crown.<ref name="WB1976" /> They [[Flemish revolts against Maximilian of Austria|openly rebelled]] twice in the period 1482–1492, attempting to regain the [[Great Privilege|autonomy]] they had enjoyed under Mary. Flemish rebels managed to capture Philip and even Maximilian himself, but they released Maximilian when Frederick III intervened.<ref name="vanleeuwen">{{Cite encyclopedia |year=2006 |title=Balancing Tradition and Rites of Rebellion: The Ritual Transfer of Power in Bruges on 12 February 1488 |encyclopedia=Symbolic Communication in Late Medieval Towns |publisher=Leuven University Press |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SEhNBaRxXWAC&pg=PA65 |author=Jacoba Van Leeuwen|isbn=9789058675224 }}</ref><ref name="buylaert">{{Cite journal |last1=Frederik Buylaert |last2=Jan Van Camp |last3=Bert Verwerft |year=2011 |editor2-last=Adrian R. Bell |title=Urban militias, nobles and mercenaries. The organization of the Antwerp army in the Flemish-Brabantine revolt of the 1480s |journal=Journal of Medieval Military History |volume=IX |editor1=Anne Curry}}</ref> In 1489, as he turned his attention to his hereditary lands, he left the Low Countries in the hands of [[Albert III, Duke of Saxony|Albert of Saxony]], who proved to be an excellent choice, as he was less emotionally committed to the Low Countries and more flexible as a politician than Maximilian, while also being a capable general. <ref>{{cite book |last1=Koenigsberger |first1=H. G. |title=Monarchies, States Generals and Parliaments: The Netherlands in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries |date=22 November 2001 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-80330-4 |page=87 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2V1dbsvEWnkC&pg=PA67 |access-date=26 October 2021 |language=en}}</ref> By 1492, rebellions were completely suppressed. Maximilian revoked the Great Privilege and established a strong ducal monarchy undisturbed by particularism. But he would not reintroduce Charles the Bold's centralizing ordinances. Since 1489 (after his departure), the government under Albert of Saxony had made more efforts in consulting representative institutions and showed more restraint in subjugating recalcitrant territories. Notables who had previously supported rebellions returned to city administrations. The Estates General continued to develop as a regular meeting place of the central government.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Tracy |first1=James D. |title=Emperor Charles V, Impresario of War: Campaign Strategy, International Finance, and Domestic Politics |date=14 November 2002 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-81431-7 |page=71 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tXKMvr09dB4C&pg=PA71 |access-date=26 October 2021 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Blockmans |first1=Willem Pieter |last2=Blockmans |first2=Wim |last3=Prevenier |first3=Walter |title=The Promised Lands: The Low Countries Under Burgundian Rule, 1369-1530 |date=1999 |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press |isbn=978-0-8122-1382-9 |page=207 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uj9nGDCiW64C&pg=PA207 |access-date=26 October 2021 |language=en}}</ref> The harsh suppression of the rebellions did have an unifying effect, in that provinces stopped behaving like separate entities each supporting a different lord.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Ellis |first1=Edward Sylvester |last2=Horne |first2=Charles Francis |title=The Story of the Greatest Nations: A Comprehensive History, Extending from the Earliest Times to the Present, Founded on the Most Modern Authorities, and Including Chronological Summaries and Pronouncing Vocabularies for Each Nation; and the World's Famous Events, Told in a Series of Brief Sketches Forming a Single Continuous Story of History and Illumined by a Complete Series of Notable Illustrations from the Great Historic Paintings of All Lands |date=1914 |publisher=Niglutsch |page=1904 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=y8RLAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA1857 |access-date=26 October 2021 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Gunn |first1=Steven |last2=Grummitt |first2=David |last3=Cools |first3=Hans |title=War, State, and Society in England and the Netherlands 1477-1559 |date=15 November 2007 |publisher=OUP Oxford |isbn=978-0-19-920750-3 |page=12 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QDpnAAAAMAAJ |access-date=26 October 2021 |language=en}}</ref> [[Helmut Koenigsberger]] opines that it was not the erratic leadership of Maximilian, who was brave but hardly understood the Netherlands, but the Estates' desire for the survival of the country that made the Burgundian monarchy survive.{{sfn|Koenigsberger|2021|p=70}} Bart van Loo agrees that his aristocratic upbringing and his militaristic tendencies did prevent him from understanding his subjects, leading to years of bloodbath, but his military leadership did save the country from France.{{sfn|Van Loo|2021|pp=558,565,567}} |

||

In early 1486, he retook Mortaigne, l'Ecluse, Honnecourt and even Thérouanne, but the same thing like in 1479 happened – he lacked financial resources to exploit and keep his gains. Only in 1492, with a stable internal situation, he was able to reconquer and keep Franche Comté and Arras on the pretext that the French had repudiated his daughter.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Gunn |first1=Steven |last2=Grummitt |first2=David |last3=Cools |first3=Hans |title=War, State, and Society in England and the Netherlands 1477-1559 |date=15 November 2007 |publisher=OUP Oxford |isbn=978-0-19-920750-3 |page=12 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QDpnAAAAMAAJ |access-date=29 October 2021 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Potter |first1=David |title=War and Government in the French Provinces |date=13 February 2003 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-89300-8 |page=42,44 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bZA5mJmoB1oC&pg=PA44 |access-date=26 October 2021 |language=en}}</ref> In 1493, Maximilian and Charles VIII of France signed the [[Treaty of Senlis]], with which Artois and Franche-Comté returned to Burgundian rule while Picardy was confirmed as French possession. The French also continued to keep the Duchy of Burgundy. Thus a large part of the Netherlands (known as the [[Seventeen Provinces]]) stayed in the Habsburg patrimony.<ref name="WB1976" /> During the time in the Low Countries, he contracted such emotional problems that except for rare, necessary occasions, he would never return to the land again after gaining control. When the Estates sent a delegation to offer him the regency after Philip's death in 1506, he evaded them for months.{{sfn|Koenigsberger|2021|p=91}}{{sfn|Van Loo|2021|p=578}} |

|||

As suzerain, Maximilian continued to involve himself with the Low Countries from afar. His son's and daughter's goverment tried to maintain a compromise between the states and the Empire.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Krahn |first1=Cornelius |title=Dutch Anabaptism: Origin, Spread, Life and Thought (1450–1600) |date=6 December 2012 |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-94-015-0609-0 |page=5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SnboCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA5 |access-date=25 October 2021 |language=en}}</ref> Philip, in particular, sought to maintain an independent Burgundian policy, which sometimes caused disagreements with his father.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Blockmans |first1=Wim |last2=Prevenier |first2=Walter |title=The Promised Lands: The Low Countries Under Burgundian Rule, 1369-1530 |date=3 August 2010 |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press |isbn=978-0-8122-0070-6 |page=211 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0Foy9GGgdcgC&pg=PA211 |access-date=1 November 2021 |language=en}}</ref>As Philip preferred to maintain peace and economic development for his land, Maximilian was left fighting [[Charles II, Duke of Guelders|Charles of Egmond]] over Guelders on his own resources. At one point, Philip let French troops supporting Guelders' resistance to his rule pass through his own land.{{sfn|Blockmans|Prevenier|2010|p=211}} Only at the end of his reign, Philip decided to deal with this threat together with his father.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Gunn |first1=Steven |last2=Grummitt |first2=David |last3=Cools |first3=Hans |title=War, State, and Society in England and the Netherlands 1477-1559 |date=15 November 2007 |publisher=OUP Oxford |isbn=978-0-19-920750-3 |page=13 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QDpnAAAAMAAJ |access-date=1 November 2021 |language=en}}</ref> By this time, Guelders had been affected by the continuous state of war and other problems. The duke of Cleves and the bishop of Utrecht, hoping to share spoils, gave Philip aid. Maximilian invested his own son with Guelders and Zutphen. Within months and with his father's skilled use of field artillery, Philip conquered the whole land and Charles of Egmond was forced to prostrate himself in front of Philip. But as Charles later escaped and Philip was at haste to make his 1506 fatal journey to Spain, troubles would soon arise again, leaving Margaret to deal with the problems. By this time, her father was less inclined to help though. He suggested to her that the Estates in the Low Countries should defend themselves, forcing her to sign the 1513 treaty with Charles.<ref> Habsburg Netherlands would only be able to incorporate Guelders and Zutphen under Charles V.{{cite book |last1=Edmundson |first1=George |title=History of Holland |date=21 September 2018 |publisher=BoD – Books on Demand |isbn=978-3-7340-5543-0 |page=21 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-VdwDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA21 |access-date=1 November 2021 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Blok |first1=Petrus Johannes |title=History of the People of the Netherlands: From the beginning of the fifteenth century to 1559 |date=1970 |publisher=AMS Press |isbn=978-0-404-00900-7 |pages=188-191 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=1ANwCltINVAC |access-date=1 November 2021 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Koenigsberger |first1=H. G. |title=Monarchies, States Generals and Parliaments: The Netherlands in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries |date=22 November 2001 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-80330-4 |page=99 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2V1dbsvEWnkC&pg=PA99 |access-date=1 November 2021 |language=en}}</ref> |

|||

==Reign in the Holy Roman Empire== |

==Reign in the Holy Roman Empire== |

||

Revision as of 13:08, 1 November 2021

| Maximilian I | |

|---|---|

Maximilian in the last year of his life, holding his personal emblem, a pomegranate. Portrait by Albrecht Dürer, 1519. | |

| Holy Roman Emperor King of the Romans King in Germany | |

| Reign | 4 February 1508 – 12 January 1519 |

| Proclamation | 4 February 1508, Trento[1] |

| Predecessor | Frederick III |

| Successor | Charles V |

| King of the Romans | |

| Reign | 16 February 1486 – 12 January 1519 |

| Coronation | 9 April 1486 |

| Predecessor | Frederick III |

| Successor | Charles V |

| Alongside | Frederick III (1486–1493) |

| Archduke of Austria | |

| Reign | 19 August 1493 – 12 January 1519 |

| Predecessor | Frederick V |

| Successor | Charles I |

| Born | 22 March 1459 Wiener Neustadt, Inner Austria |

| Died | 12 January 1519 (aged 59) Wels, Upper Austria |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | |

| Issue more... | |

| House | Habsburg |

| Father | Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor |

| Mother | Eleanor of Portugal |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

Maximilian I (22 March 1459 – 12 January 1519) was King of the Romans from 1486 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1508 until his death. He was never crowned by the pope, as the journey to Rome was blocked by the Venetians.[2] He was instead proclaimed emperor elect by Pope Julius II at Trent, thus breaking the long tradition of requiring a Papal coronation for the adoption of the Imperial title. Maximilian was the son of Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor, and Eleanor of Portugal. He ruled jointly with his father for the last ten years of the latter's reign, from c. 1483 until his father's death in 1493.

Maximilian expanded the influence of the House of Habsburg through war and his marriage in 1477 to Mary of Burgundy, the ruler of the Burgundian State, heir of Charles the Bold, though he also lost his family's original lands in today's Switzerland to the Swiss Confederacy. Through marriage of his son Philip the Handsome to eventual queen Joanna of Castile in 1498, Maximilian helped to establish the Habsburg dynasty in Spain, which allowed his grandson Charles to hold the thrones of both Castile and Aragon.[3] The historian Thomas A.Brady Jr. describes him as "the first Holy Roman Emperor in 250 years who ruled as well as reigned" and also, the "ablest royal warlord of his generation."[4]

Nicknamed "Coeur d’acier" (“Heart of steel”) by Olivier de la Marche and later historians (either as praise for his courage and martial qualities or reproach for his ruthlessness as a warlike ruler),[5][6] Maximilian has entered the public consciousness as "the last knight" (der letzte Ritter), especially since the eponymous poem by Anastasius Grün was published (although the nickname likely existed even in Maximilian's lifetime).[7] Scholarly debates still discuss whether he was truly the last knight (either as an idealized medieval ruler leading people on horseback, or a Don Quixote-type dreamer and misadventurer), or the first Renaissance prince — an amoral Machiavellian politician who carried his family "to the European pinnacle of dynastic power" largely on the back of loans.[8][9] Historians of the second half of the nineteenth century like Leopold von Ranke tended to criticize Maximilian for putting the interest of his dynasty above that of Germany, hampering the nation's unification process. Ever since Hermann Wiesflecker's Kaiser Maximilian I. Das Reich, Österreich und Europa an der Wende zur Neuzeit (1971-1986) became the standard work, a much more positive image of the emperor has emerged. He is seen as an essentially modern, innovative ruler who carried out important reforms and promoted significant cultural achievements, even if the financial price weighed hard on the Austrians and his military expansion caused the deaths and sufferings of tens of thousands of people.[6][10][11]

Background and childhood

Maximilian was born at Wiener Neustadt on 22 March 1459. His father, Frederick III, Holy Roman Emperor, named him for an obscure saint, Maximilian of Tebessa, who Frederick believed had once warned him of imminent peril in a dream. In his infancy, he and his parents were besieged in Vienna by Albert of Austria. One source relates that, during the siege's bleakest days, the young prince wandered about the castle garrison, begging the servants and men-at-arms for bits of bread.[12] The young prince was an excellent hunter, his favorite hobby was hunting for birds as a horse archer.

At the time, the dukes of Burgundy, a cadet branch of the French royal family, with their sophisticated nobility and court culture, were the rulers of substantial territories on the eastern and northern boundaries of France. The reigning duke, Charles the Bold, was the chief political opponent of Maximilian's father Frederick III. Frederick was concerned about Burgundy's expansive tendencies on the western border of his Holy Roman Empire, and, to forestall military conflict, he attempted to secure the marriage of Charles' only daughter, Mary of Burgundy, to his son Maximilian. After the Siege of Neuss (1474–75), he was successful. The wedding between Maximilian and Mary took place on 19 August 1477.[13]

Reign in Burgundy and the Netherlands

Maximilian's wife had inherited the large Burgundian domains in France and the Low Countries upon her father's death in the Battle of Nancy on 5 January 1477. Already before his coronation as the King of the Romans in 1486, Maximilian decided to secure this distant and extensive Burgundian inheritance to his family, the House of Habsburg, at all costs.[15]

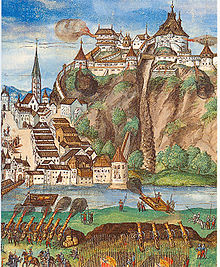

The Duchy of Burgundy was also claimed by the French crown under Salic Law,[16] with Louis XI of France vigorously contesting the Habsburg claim to the Burgundian inheritance by means of military force. Maximilian at once undertook the defence of his wife’s dominions. Without support from the Empire, he carried out a campaign against the French during 1478–1479 and reconquered Le Quesnoy, Conde and Antoing.[17] He defeated the French forces at Guinegatte, the modern Enguinegatte, on the 7th of August 1479[18] Despite winning, Maximilian had to abandon the siege of Thérouanne and disband his army, either because the Netherlanders did not want him to become too strong or because his treasury was empty. The battle was an important mark in military history though: the Burgundian pikemen were the precursors of the Landsknechte, while the French side derived the momentum for military reform from their loss.[19]

Maximilian and Mary's wedding contract stipulated that their children would succeed them but that the couple could not be each other's heirs. Mary tried to bypass this rule with a promise to transfer territories as a gift in case of her death, but her plans were confounded. After Mary's death in a riding accident on 27 March 1482 near the Wijnendale Castle, Maximilian's aim was now to secure the inheritance to his and Mary's son, Philip the Handsome.[15]

The Guinegate victory made Maximilian popular, but as an inexperienced ruler, he hurt himself politically by trying to centralize authority without respecting traditional rights and consulting relevant political bodies. The Belgian historian Eugène Duchesne comments that these years were among the saddest and most turbulent in the history of the country, and despite his later great imperial career, Maximilian unfortunately could never compensate for the mistakes he made as regent in this period. [21][22] Some of the Netherlander provinces were hostile to Maximilian, and, in 1482, they signed a treaty with Louis XI in Arras that forced Maximilian to give up Franche-Comté and Artois to the French crown.[16] They openly rebelled twice in the period 1482–1492, attempting to regain the autonomy they had enjoyed under Mary. Flemish rebels managed to capture Philip and even Maximilian himself, but they released Maximilian when Frederick III intervened.[23][24] In 1489, as he turned his attention to his hereditary lands, he left the Low Countries in the hands of Albert of Saxony, who proved to be an excellent choice, as he was less emotionally committed to the Low Countries and more flexible as a politician than Maximilian, while also being a capable general. [25] By 1492, rebellions were completely suppressed. Maximilian revoked the Great Privilege and established a strong ducal monarchy undisturbed by particularism. But he would not reintroduce Charles the Bold's centralizing ordinances. Since 1489 (after his departure), the government under Albert of Saxony had made more efforts in consulting representative institutions and showed more restraint in subjugating recalcitrant territories. Notables who had previously supported rebellions returned to city administrations. The Estates General continued to develop as a regular meeting place of the central government.[26][27] The harsh suppression of the rebellions did have an unifying effect, in that provinces stopped behaving like separate entities each supporting a different lord.[28][29] Helmut Koenigsberger opines that it was not the erratic leadership of Maximilian, who was brave but hardly understood the Netherlands, but the Estates' desire for the survival of the country that made the Burgundian monarchy survive.[30] Bart van Loo agrees that his aristocratic upbringing and his militaristic tendencies did prevent him from understanding his subjects, leading to years of bloodbath, but his military leadership did save the country from France.[31]

In early 1486, he retook Mortaigne, l'Ecluse, Honnecourt and even Thérouanne, but the same thing like in 1479 happened – he lacked financial resources to exploit and keep his gains. Only in 1492, with a stable internal situation, he was able to reconquer and keep Franche Comté and Arras on the pretext that the French had repudiated his daughter.[32][33] In 1493, Maximilian and Charles VIII of France signed the Treaty of Senlis, with which Artois and Franche-Comté returned to Burgundian rule while Picardy was confirmed as French possession. The French also continued to keep the Duchy of Burgundy. Thus a large part of the Netherlands (known as the Seventeen Provinces) stayed in the Habsburg patrimony.[16] During the time in the Low Countries, he contracted such emotional problems that except for rare, necessary occasions, he would never return to the land again after gaining control. When the Estates sent a delegation to offer him the regency after Philip's death in 1506, he evaded them for months.[34][20]

As suzerain, Maximilian continued to involve himself with the Low Countries from afar. His son's and daughter's goverment tried to maintain a compromise between the states and the Empire.[35] Philip, in particular, sought to maintain an independent Burgundian policy, which sometimes caused disagreements with his father.[36]As Philip preferred to maintain peace and economic development for his land, Maximilian was left fighting Charles of Egmond over Guelders on his own resources. At one point, Philip let French troops supporting Guelders' resistance to his rule pass through his own land.[37] Only at the end of his reign, Philip decided to deal with this threat together with his father.[38] By this time, Guelders had been affected by the continuous state of war and other problems. The duke of Cleves and the bishop of Utrecht, hoping to share spoils, gave Philip aid. Maximilian invested his own son with Guelders and Zutphen. Within months and with his father's skilled use of field artillery, Philip conquered the whole land and Charles of Egmond was forced to prostrate himself in front of Philip. But as Charles later escaped and Philip was at haste to make his 1506 fatal journey to Spain, troubles would soon arise again, leaving Margaret to deal with the problems. By this time, her father was less inclined to help though. He suggested to her that the Estates in the Low Countries should defend themselves, forcing her to sign the 1513 treaty with Charles.[39][40][41]

Reign in the Holy Roman Empire

Recapture of Austria

Maximilian was elected King of the Romans on 16 February 1486 in Frankfurt-am-Main at his father's initiative and crowned on 9 April 1486 in Aachen. Much of Austria was under Hungarian rule, as a result of the Austrian–Hungarian War (1477–1488). Maximilian was now a king without lands. After the death of king Matthias Corvinus of Hungary, from July 1490, Maximilian began a series of short sieges that reconquered cities and fortresses that his father had lost in Austria. Maximilian entered Vienna without siege, already evacuated by the Hungarians, in August 1490. He was injured while attacking the citadel guarded by a garrison of 400 Hungarians troops who twice repelled his forces, but after some days they surrendered.[42][43] With money from Innsbruck and southern German towns, he raised enough cavalry and Landsknechte to campaign into Hungary itself. Despite Hungary's gentry's hostility to the Habsburg, he managed to gain many supporters, including several of Corvinus's former supporters. One of them, Jakob Székely, handed over the Styrian castles to him.[44] He claimed his status as King of Hungary, demanding allegiance through Stephen of Moldavia. In seven weeks, they conquered a quarter of Hungary. His mercenaries committed the atrocity of totally sacking Székesfehérvár, the country's main fortress.[45] When encountering the frost, the troops refused to continue the war though, requesting Maximilian to double their pay, which he could not afford. The revolt turned the situation in favour of the Jagiellonian forces.[46] Maximilian was forced to return. He depended on his father and the territorial estates for financial support. Soon he reconquered Lower and Inner Austria for his father, who returned and settled at Linz. Worrying about his son's adventurous tendencies, Frederick decided to starve him financially though.

The crown of Hungary thus fell to King Vladislaus II.[46] In 1491, they signed the peace treaty of Pressburg, which provided that Maximilian recognized Vladislaus as King of Hungary, but the Habsburgs would inherit the throne on the extinction of Vladislaus's male line and the Austrian side also received 100,000 golden florins as war reparations.[47]

In addition, the County of Tyrol and Duchy of Bavaria went to war in the late 15th century. Bavaria demanded money from Tyrol that had been loaned on the collateral of Tyrolean lands. In 1490, the two nations demanded that Maximilian I step in to mediate the dispute. His Habsburg cousin, the childless Archduke Sigismund, was negotiating to sell Tyrol to their Wittelsbach rivals rather than let Emperor Frederick inherit it. Maximilian's charm and tact though led to a reconciliation and a reunited dynastic rule in the 1490.[48] Because Tyrol had no law code at this time, the nobility freely expropriated money from the populace, which caused the royal palace in Innsbruck to fester with corruption. After taking control, Maximilian instituted immediate financial reform. Gaining theoretical control of Tyrol for the Habsburgs was of strategic importance because it linked the Swiss Confederacy to the Habsburg-controlled Austrian lands, which facilitated some imperial geographic continuity.

Maximilian became ruler of the Holy Roman Empire upon the death of his father in 1493.

Italian and Swiss wars

As the Treaty of Senlis had resolved French differences with the Holy Roman Empire, King Louis XII of France had secured borders in the north and turned his attention to Italy, where he made claims for the Duchy of Milan. In 1499/1500 he conquered it and drove the Sforza regent Lodovico il Moro into exile.[49] This brought him into a potential conflict with Maximilian, who on 16 March 1494 had married Bianca Maria Sforza, a daughter of Galeazzo Maria Sforza, duke of Milan.[16][49] However, Maximilian was unable to hinder the French from taking over Milan.[49] The prolonged Italian Wars resulted[16] in Maximilian joining the Holy League to counter the French. In 1513, with Henry VIII of England, Maximilian won an important victory at the battle of the Spurs against the French, stopping their advance in northern France. His campaigns in Italy were not as successful, and his progress there was quickly checked. Maximilian's Italian campaigns tend to be criticized for being wasteful. Despite the emperor's work in enhancing his army technically and organization-wise, due to financial difficulties, the forces he could muster were always too small to make a decisive difference.[50][51]

The situation in Italy was not the only problem Maximilian had at the time. The Swiss won a decisive victory against the Empire in the Battle of Dornach on 22 July 1499. Maximilian had no choice but to agree to a peace treaty signed on 22 September 1499 in Basel that granted the Swiss Confederacy independence from the Holy Roman Empire.

Jewish policy

Jewish policy under Maximilian fluctuated greatly, usually influenced by financial considerations and the emperor's vacillating attitude when facing opposing views. In 1496, Maximilian issued a decree which expelled all Jews from Styria and Wiener Neustadt.[52] Between 1494 and 1510, he authorized no less than thirteen expulsions of Jews in return of sizeable fiscal compensations from local government (The expelled Jews were allowed to resettle in Lower Austria. Buttaroni comments that this inconsistency showed that even Maximilian himself did not believe his expulsion decision was just.).[53][54] After 1510 though, this happened only once, and he showed an unusually resolute attitude in resisting a campaign to expel Jews from Regensburg. David Price comments that during the first seventeen years of his reign, he was a great threat to the Jews, but after 1510, even if his attitude was still exploitative, his policy gradually changed. A factor that probably played a role in the change was Maximilian's success in expanding imperial taxing over German Jewry: at this point, he probably considered the possibility of generating tax money from stable Jewish communities, instead of temporary financial compensations from local jurisdictions who seeked to expel Jews.[55]

In 1509, relying on the influence of Kunigunde, Maximilian's pious sister and the Cologne Dominicans, the anti-Jewish agitator Johannes Pfefferkorn was authorized by Maximilian to confiscate all offending Jewish books (including prayer books), except the Bible. The confiscations happened in Frankfurt, Bingen, Mainz and other German cities. Responding to the order, the archbishop of Mainz, the city council of Frankfurt and various German princes tried to intervene in defense the Jews. Maximilian consequently ordered the confiscated books to be returned. On May 23, 1510 though, influenced by a supposed "host desecration" and blood libel in Brandenburg, as well as pressure from Kunigunde, he ordered the creation of an investigating commission and asked for expert opinions from German universities and scholars. The prominent humanist Johann Reuchlin argued strongly in defense of the Jewish books, especially the Talmud.[56] Reuchlin's arguments seemed to leave an impression on the emperor, who gradually developed an intellectual interest in the Talmud and other Jewish books. In 1514, he appointed Paulus Ricius, a Jew who converted to Christianity, as his personal physician. He was more interested in Ricius's Hebrew skills than in his medical abilities though. On 1515, he reminded his treasurer Jakob Villinger that Ricius was admitted for the purpose of translating the Talmud into Latin, and urged Villinger to keep an eye on him. Perhaps overwhelmed by the emperor's request, Ricius only managed to translate 2 out of 63 Mishna tractates before the emperor's death.[57]

Reforms

Within the Holy Roman Empire, Maximilian faced pressure from local rulers who believed that the King's continued wars with the French to increase the power of his own house were not in their best interests. There was also a consensus that deep reforms were needed to preserve the unity of the Empire.[60] The reforms, which had been delayed for a long time, were launched in the 1495 Reichstag at Worms. A new organ was introduced, the Reichskammergericht, that was to be largely independent from the Emperor. A new tax was launched to finance it, the Gemeine Pfennig, though its collection was never fully successful.[60] The local rulers wanted more independence from the Emperor and a strengthening of their own territorial rule. This led to Maximilian agreeing to establish an organ called the Reichsregiment, which met in Nuremberg and consisted of the deputies of the Emperor, local rulers, commoners, and the prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire. The new organ proved politically weak, and its power returned to Maximilian in 1502.[49] To create a rival for the Reichskammergericht, Maximilian establish the Reichshofrat, which had its seat in Vienna. Unlike the Reichskammergericht, the Reichshofrat looked into criminal matters and even allowed the emperors the means to depose rulers who did not live up to expectations. During Maximilian's reign, this Council was not popular though.[61]

The most important governmental changes targeted the heart of the regime: the chancery. Early in Maximilian’s reign, the Court Chancery at Innsbruck competed with the Imperial Chancery (which was under the elector—archbishop of Mainz, the senior Imperial chancellor). By referring the political matters in Tyrol, Austria as well as Imperial problems to the Court Chancery, Maximilian gradually centralized its authority. The two chanceries became combined in 1502.[59] In 1496, the emperor created a general treasury (Hofkammer) in Innsbruck, which became responsible for all the hereditary lands. The chamber of accounts (Raitkammer) at Vienna was made subordinate to this body.[62] Under Paul von Liechtenstein, the Hofkammer was entrusted with not only hereditary lands' affairs, but Maximilian's affairs as the German king too.[63]

Due to the difficult external and internal situation he faced, Maximilian also felt it necessary to introduce reforms in the historic territories of the House of Habsburg in order to finance his army. Using Burgundian institutions as a model, he attempted to create a unified state. Michael Erbe opines that the model was not very successful, but one of the lasting results was the creation of three different subdivisions of the Austrian lands: Lower Austria, Upper Austria, and Vorderösterreich.[49]

Historian Joachim Whaley points out that there are usually two opposite views on Maximilian's rulership: one side is represented by the works of nineteenth century historians like Heinrich Ullmann or Leopold von Ranke, which criticize him for selfishly exploiting the German nation and putting the interest of his dynasty over his Germanic nation, thus impeding the unification process; the more recent side is represented by Hermann Wiesflecker's biography of 1971-86, which praises him for being "a talented and successful ruler, notable not only for his Realpolitik but also for his cultural activities generally and for his literary and artistic patronage in particular".[64][65]

According to Whaley, if Maximilian ever saw Germany as a source of income and soldiers only, he failed miserably in extracting both. His hereditary lands and other sources always contributed much more (the Estates gave him the equivalent of 50,000 gulden per year, a lower than even the taxes paid by Jews in both the Reich and hereditary lands, while Austria contributed 500,000 to 1,000,000 gulden per year). On the other hand, the attempts he demonstrated in building the imperial system alone shows that he did consider the German lands "a real sphere of government in which aspirations to royal rule were actively and purposefully pursue." Whaley notes that, despite struggles, what emerged at the end of Maximilian's rule was a strengthened monarchy and not an oligarchy of princes. If he was usually weak when trying to act as a monarch and using imperial instituations like the Reichstag, Maximilian's position was often strong when acting as a neutral overlord and relying on regional leagues of weaker principalities such as the Swabian league, as shown in his ability to call on money and soldiers to mediate the Bavaria dispute in 1504, after which he gained significant territories in Alsace, Swabia and Tyrol. His fiscal reform in his hereditary lands provided a model for other German princes.[66] Benjamin Curtis opines that while Maximilian was not able to fully create a common government for his lands (although the chancellery and court council were able to coordinates affairs across the realms), he strengthened key administrative functions in Austria and created central offices to deal with financial, political and judicial matters - these offices replaced the feudal system and became representative of a more modern system that was administered by professionalized officials. After two decades of reforms, the emperor retained his position as first emong equals, while the empire gained common institutions through which the emperor shared power with the estates.[67]

Maximilian was always troubled by financial shortcomings; his income never seemed to be enough to sustain his large-scale goals and policies. For this reason he was forced to take substantial credits from Upper German banker families, especially from the Baumgarten, Fugger and Welser families. Jörg Baumgarten even served as Maximilian's financial advisor. The Fuggers, who dominated the copper and silver mining business in Tyrol, provided a credit of almost 1 million gulden for the purpose of bribing the prince-electors to choose Maximilian's grandson Charles V as the new Emperor. At the end of Maximilian's rule, the Habsburgs' mountain of debt totalled six million gulden, corresponding to a decade's worth of tax revenues from their inherited lands. It took until the end of the 16th century to repay this debt.

In 1508, Maximilian, with the assent of Pope Julius II, took the title Erwählter Römischer Kaiser ("Elected Roman Emperor"), thus ending the centuries-old custom that the Holy Roman Emperor had to be crowned by the Pope.

Tu felix Austria nube

As part of the Treaty of Arras, Maximilian betrothed his three-year-old daughter Margaret to the Dauphin of France (later Charles VIII), son of his adversary Louis XI. Under the terms of Margaret's betrothal, she was sent to Louis to be brought up under his guardianship. Despite Louis's death in 1483, shortly after Margaret arrived in France, she remained at the French court. The Dauphin, now Charles VIII, was still a minor, and his regent until 1491 was his sister Anne.[68][69]

Dying shortly after signing the Treaty of Le Verger, Francis II, Duke of Brittany, left his realm to his daughter Anne. In her search of alliances to protect her domain from neighboring interests, she betrothed Maximilian I in 1490. About a year later, they married by proxy.[70][71][72]

However, Charles and his sister wanted her inheritance for France. So, when the former came of age in 1491, and taking advantage of Maximilian and his father's interest in the succession of their adversary Mathias Corvinus, King of Hungary,[73] Charles repudiated his betrothal to Margaret, invaded Brittany, forced Anne of Brittany to repudiate her unconsummated marriage to Maximilian, and married Anne of Brittany himself.[74][75][76]

Margaret then remained in France as a hostage of sorts until 1493, when she was finally returned to her father with the signing of the Treaty of Senlis.[77][78]

In the same year, as the hostilities of the lengthy Italian Wars with France were in preparation,[79] Maximilian contracted another marriage for himself, this time to Bianca Maria Sforza, daughter of Galeazzo Maria Sforza, Duke of Milan, with the intercession of his brother, Ludovico Sforza,[80][81][82][83] then regent of the duchy after the former's death.[84]

Years later, in order to reduce the growing pressures on the Empire brought about by treaties between the rulers of France, Poland, Hungary, Bohemia, and Russia, as well as to secure Bohemia and Hungary for the Habsburgs, Maximilian met with the Jagiellonian kings Ladislaus II of Hungary and Bohemia and Sigismund I of Poland at the First Congress of Vienna in 1515. There they arranged for Maximilian's granddaughter Mary to marry Louis, the son of Ladislaus, and for Anne (the sister of Louis) to marry Maximilian's grandson Ferdinand (both grandchildren being the children of Philip the Handsome, Maximilian's son, and Joanna of Castile).[85][86] The marriages arranged there brought Habsburg kingship over Hungary and Bohemia in 1526.[87][88] Both Anne and Louis were adopted by Maximilian following the death of Ladislaus.[citation needed]

Thus Maximilian through his own marriages and those of his descendants (attempted unsuccessfully and successfully alike) sought, as was current practice for dynastic states at the time, to extend his sphere of influence.[88] The marriages he arranged for both of his children more successfully fulfilled the specific goal of thwarting French interests, and after the turn of the sixteenth century, his matchmaking focused on his grandchildren, for whom he looked away from France towards the east.[88][89] These political marriages were summed up in the following Latin elegiac couplet: Bella gerant aliī, tū fēlix Austria nūbe/ Nam quae Mars aliīs, dat tibi regna Venus, "Let others wage war, but thou, O happy Austria, marry; for those kingdoms which Mars gives to others, Venus gives to thee."[90]

Contrary to the implication of this motto though, Maximilian waged war aplenty (In four decades of ruling, he waged 27 wars in total).[91] His general strategy was to combine his intricate systems of alliance, military threats and offers of marriage to realize his expansionist ambitions. Using overtures to Russia, Maximilian succeeded in coercing Bohemia, Hungary and Poland into acquiesce in the Habsburgs' expansionist plans. Combining this tactic with military threats, he was able to gain the favourable marriage arrangements In Hungary and Bohemia (which were under the same dynasty).[92]

At the same time, his sprawling panoply of territories as well as potential claims constituted a threat to France, thus forcing Maximilian to continuously launch wars in defense of his possessions in Burgundy, the Low Countries and Italy against four generations of French kings (Louis XI, Charles VIII, Louis XII, Francis I). Coalitions he assembled for this purpose sometimes consisted of non-imperial actors like England. Edward J. Watts comments that the nature of these wars was dynastic, rather than imperial.[93]

Fortune was also a factor that helped to bring about the results of his marriage plans. The double marriage could have given the Jagiellon a claim in Austria, while a potential male child of Margaret and John, a prince of Spain, would have had a claim to a portion of the maternal grandfather's possessions as well. But as it turned out, Vladislaus's male line became extinct, while the frail John died (possibly of overindulgence in sexual activities with his bride) without offsprings, so Maximilian's male line was able to claim the thrones.[94]

Death and succession

Maximilian's policies in Italy had been unsuccessful, and after 1517 Venice reconquered the last pieces of their territory. Maximilian began to focus entirely on the question of his succession. His goal was to secure the throne for a member of his house and prevent Francis I of France from gaining the throne; the resulting "election campaign" was unprecedented due to the massive use of bribery.[95] The Fugger family provided Maximilian a credit of one million gulden, which was used to bribe the prince-electors.[96] However, the bribery claims have been challenged.[97] At first, this policy seemed successful, and Maximilian managed to secure the votes from Mainz, Cologne, Brandenburg and Bohemia for his grandson Charles V. The death of Maximilian in 1519 seemed to put the succession at risk, but in a few months the election of Charles V was secured.[49]

In 1501, Maximilian fell from his horse and badly injured his leg, causing him pain for the rest of his life. Some historians have suggested that Maximilian was "morbidly" depressed: from 1514, he travelled everywhere with his coffin.[98] Maximilian died in Wels, Upper Austria, and was succeeded as Emperor by his grandson Charles V, his son Philip the Handsome having died in 1506. For penitential reasons, Maximilian gave very specific instructions for the treatment of his body after death. He wanted his hair to be cut off and his teeth knocked out, and the body was to be whipped and covered with lime and ash, wrapped in linen, and "publicly displayed to show the perishableness of all earthly glory".[99] Although he is buried in the Castle Chapel at Wiener Neustadt, an extremely elaborate cenotaph tomb for Maximilian is in the Hofkirche, Innsbruck, where the tomb is surrounded by statues of heroes from the past.[100] Much of the work was done in his lifetime, but it was not completed until decades later.[citation needed]

Legacy

Military innovation, chivalry and equipments

Maximilian is generally considered an able commander (although he lost many wars, usually due to the lack of financial resources) and a military innovator who contributed to the modernization of warfare.[101] He and his condottiero George von Frundsberg organized the first formations of the Landsknechte based on inspiration from Swiss pikement, but increased the ratio of pikemen and favoured handgunners over the crossbowmen, with new tactics being developed, leading to improvement in performance. Discipline, drilling and a highly developed staff by the standard of the era were also instilled.[102][103][104] The "war apparatus" he created played an essential role in Austria’s later rank as great power. Maximilian was the founder and organiser of the arms industry of the Habsburgs.[105] He started the standardization of the artillery (according to the weight of the cannon balls) and made them more mobile.[10] He sponsored new types of cannons, initiated many innovations that improved the range and damage so that cannons worked better against thick walls, and concerned himself with the metallurgy, as cannons often exploded when ignited and caused damage among his own troups.[106] According to contemporary accounts, he could field an artillery of 105 cannons, including both iron and bronze guns of various sizes.[107] The artillery force is considered by some to be the most developed of the day.[108][109] The arsenal in Innsbruck, created by Maximilian, was one of the most notable artillery arsenal in Europe.[110] His typical tactic was: artillery should attack first, the cavalry would act as shock troups and attack the flanks, infantry fought in tightly-knitted formation at the middle.[106]

Maximilian was described by the nineteenth century politician Anton Alexander Graf von Auersperg as 'the last knight' (der letzte Ritter) and this epithet has stuck to him the most.[112] Some historians note that the epithet rings true, yet ironic: as the father of the Landsknechte (of which the paternity he shared with George von Frundsberg), he ended the combat supremacy of the cavalry and his death heralded the military revolution of the next two centuries.[113][114] He threw his own weight behind the promotion of the infantry soldier, leading them in battles on foot with a pike on his shoulder and giving the commanders honours and titles.[115] With Maximilian's establishment and use of the Landsknechte, the military organisation in Germany was altered in a major way. Here began the rise of military enterprisers, who raised mercenaries with a system of subcontractors to make war on credit, and acted as the commanding generals of their own armies.[116][117] Maximilian became an expert military enterpriser himself, leading his father to consider him a spendthrift military adventurer who wandered into new wars and debts while still recovering from the previous campaigns.[118]

While favouring more modern methods in his actual military undertakings, Maximilian had a genuine interest in promoting chivalric traditions like the tournament, being an exceptional jouster himself. The tournaments helped to enhance his personal image and solidify a network of princes and nobles over whom he kept a close watch, fostering fidelity and fraternity among the competitors. Taking inspiration from the Burgundy tournament, he developed the German tournament into a distinctive entity.[119] In addition, during at least two occasions in his campaigns, he challenged and killed French knights in duel-like preludes to battles.[120]

Knights reacted to their decreased condition and loss of privileges in different ways. Some asserted their traditional rights in violent ways and became robber knights like Götz von Berlichingen. The knights as a social group became an obstacle to Maximilian's law and order and the relationship between them and "the last knight" became antagonistic.[106] Some probably also felt slighted by the way imperial propaganda presented Maximilian as the sole defender of knightly values.[123] In the Diet of Worms in 1495, the emperor, the archbishops, great princes and free cities joined force to initiate the Perpetual Land Peace (Ewige Landfriede), forbidding all private feuding, in order to protect the rising tide of commerce.[124] The tournament sponsored by the emperor was thus a tool to appease the knights, although it became a recreational, yet still deadly extreme sport.[106] After spending 20 years creating and supporting policies against the knights though, Maximilian changed his ways and began trying to engage them to integrate them into his frame of rulership. In 1517, he lifted the ban on Franz von Sickingen, a leading figure among the knights and took him into his service. In the same year, he summoned the Rhenish knights and introduced his Ritterrecht (Knight's Rights), which would provide the free knight with a special law court, in exchange of their oaths for being obedient to the emperor and abstaining from evil deeds. He did not succeed in collecting taxes from them or creating a knights' association, but an ideology or frame emerged, that allowed the knights to retain their freedom while fostering the relationship between the crown and the sword. [125][126]

Maximilian had a great passion for armour, not only as equipment for battle or tournaments, but as an art form. He prided himself on his armor designing expertise and knowledge of metallurgy. Under his patronage, "the art of the armorer blossomed like never before." Master armorers across Europe like Lorenz Helmschmid and Franck Scroo created custom-made armors that often served as extravagant gifts to display Maximilian's generosity and devices that would produce special effects (often initiated by the emperor himself) in tournaments.[127] The style of armour that became popular during the second half of his reign featured elaborate fluting and metalworking, and became known as Maximilian armour. It emphasized the details in the shaping of the metal itself, rather than the etched or gilded designs popular in the Milanese style. Maximilian also gave a bizarre jousting helmet as a gift to King Henry VIII – the helmet's visor features a human face, with eyes, nose and a grinning mouth, and was modelled after the appearance of Maximilian himself.[128] It also sports a pair of curled ram's horns, brass spectacles, and even etched beard stubble.[128]

While he was unconcerned with the disappearance or weakening of the knight class due to the development of artillery and infantry, Maximilian worried greatly about the vulnerablity of ibexes, described by him as "noble creatures", in front of handguns and criticized the peasants in particular for having no moderation.[129] In 1517, the emperor banned the manufacturing and possession of the wheellock, which was designed and especially effective for hunting.[130] Another possible reason for this earliest attempt at gun control might be related to worries about the spreading of crimes.[131]

Cultural patronage, reforms and image building

Maximilian was a keen supporter of the arts and sciences, and he surrounded himself with scholars such as Joachim Vadian and Andreas Stoberl (Stiborius), promoting them to important court posts. Many of them were commissioned to assist him complete a series of projects, in different art forms, intended to glorify for posterity his life and deeds and those of his Habsburg ancestors.[132][133] He referred to these projects as Gedechtnus ("memorial"),[133][134] which included a series of stylised autobiographical works: the epic poems Theuerdank and Freydal, and the chivalric novel Weisskunig, both published in editions lavishly illustrated with woodcuts.[132] In this vein, he commissioned a series of three monumental woodblock prints: The Triumphal Arch (1512–18, 192 woodcut panels, 295 cm wide and 357 cm high – approximately 9'8" by 11'8½"); and a Triumphal Procession (1516–18, 137 woodcut panels, 54 m long), which is led by a Large Triumphal Carriage (1522, 8 woodcut panels, 1½' high and 8' long), created by artists including Albrecht Dürer, Albrecht Altdorfer and Hans Burgkmair.[135][136] According to The Last Knight: The Art, Armor, and Ambition of Maximilian I, Maximilian dictated large parts of the books to his secretary and friend Marx Treitzsaurwein who did the rewriting.[137] Authors of the book Emperor Maximilian I and the Age of Durer cast doubt on his role as a true patron of the arts though, as he tended to favor pragmatic elements over high arts.[138] On the other hand, he was a perfectionist who involved himself with every stage of the creative processes. His goals extended far beyond the emperor's own glorification too: commemoration also included the documentation in details of the presence and the restoration of source materials and precious artifacts.[139]

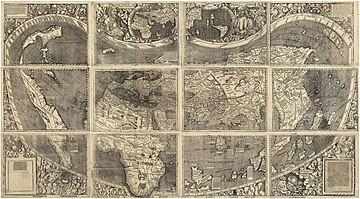

An area that saw many new developments under Maximilian was cartography, of which the important center in Germany was Nuremberg. In 1515 Dürer and Stabius created the first world map projected on a solid geometric sphere. Johannes Schöner then created terrestrial globes and celestial globe with many useful cosmographic developments, a more accurate shape of Europe and new islands discovered by Ferdinand Magellan.[140][141] The cartographers Martin Waldseemüller and Matthias Ringmann dedicated their famous work Universalis Cosmographia to Maximilian, although the direct backer was Rene II of Loraine.[142] The development in cartography was tied to the emperor's special interest in sea route exploration, as an activity concerning his global monarchy concept, and his responsibilities as Duke consort to Mary of Burgundy, grandfather of the future ruler of Spain as well as ally and close relation to Portuguese kings. He sent men like Martin Behaim und Hieronymus Münzer to the Portuguese court to cooperate in their exploration efforts as well as his own representatives.[143] Another involved in the network was the Flemish Josse van Huerter or Joss de Utra who would become the first settler of the island of Faial in the Portuguese Azores. Maximilian also played an essential role in connecting the financial houses Augsburg and Nuremberg (including the companies of Höchstetter, Fugger and Welser etc) to Portuguese expeditions. In exchange for financial backing, King Manuel provided German investors with generous priveleges. The humanist Conrad Peutinger was an important agent who acted as advisor to financiers, translator of voyage records and imperial councillor.[144]

Under his rule, the University of Vienna reached its apogee as a centre of humanistic thought. He established the College of Poets and Mathematicians which was incorporated into the university.[145] Maximilian invited Conrad Celtis, the leading German scientist of their day to University of Vienna. Celtis found the Sodalitas litteraria Danubiana (which was also supported by Maximilian), an association of scholars from the Danube area, to support literature and humanist thought. Maximilian supported and utilized the humanists partly for propaganda effect, partly for his genealogical projects, but he also employed several as secretaries and counsellors - in their selection he rejected class barriers, believing that "intelligent minds deriving their nobility from God", even if this caused conflicts (even physical attacks) with the nobles. He relied on his humanists to create a nationalistic imperial myth, in order to unify the Reich against the French in Italy, as pretext for a later Crusade (the Estates protested against investing their resources in Italy though).[146] Maximilian told his Electors each to establish a university in their realm. Thus in 1502 and 1506, together with the Elector of Saxony and the Elector of Brandenburg, respectively, he co-found the University of Wittenberg and the University of Frankfurt.[147] The University of Wittenberg was the first German university established without a Papal Bull, signifying the secular imperial authority concerning universities. This first center in the North where old Latin scholarly traditions were overthrown would become the home of Luther and Melanchthon.[148]

He had notable influence on the development of the musical tradition in Austria and Germany as well. Several historians credit Maximilian with playing the decisive role in making Vienna the music capital of Europe.[149][150] Under his reign, the Habsburg musical culture reached its first high point[151] and he had at his service the best musicians in Europe.[152] He began the Habsburg tradition of supporting large-scale choirs, which he staffed with the brilliant musicians of his days like Paul Hofhaimer, Heinrich Isaac and Ludwig Senfl.[153] His children inherited the parents' passion for music and even in their father's lifetime, supported excellent chapels in Brussels and Malines, with masters such as Alexander Agricola, Marbriano de Orto (who worked for Philip), Pierre de La Rue and Josquin Desprez (who worked for Margaret).[154] After witnessing the brilliant Burgundian court culture, he looked to the Burgundian court chapel to create his own imperial chapel. As he was always on the move, he brought the chapel as well as his whole peripatetic court with him. In 1498 though, he established the imperial chapel in Vienna, under the direction of Goerge Slatkonia, who would later become the Bishop of Vienna.[155] Music benefitted greatly through the cross-fertilization between several centres in Burgundy, Italy, Austria and Tyrol (where Maximilian inherited the chapel of his uncle Sigismund).[156]

Among some authors, Maximilian has a reputation as the "media emperor". The historian Larry Silver describes him as the first ruler who realized and exploited the propaganda potential of the print press both for images and texts.[157] The reproduction of the Triumphal Arch (mentioned above) in printed form is an example of art in service of propaganda, made available for the public by the economical method of printing (Maximilian did not have money to actually construct it). At least 700 copies were created in the first edition and hung in ducal palaces and town halls through the Reich.[158]

Historian Joachim Whaley comments that: "By comparison with the extraordinary range of activities documented by Silver, and the persistence and intensity with which they were pursued, even Louis XIV appears a rather relaxed amateur." Whaley notes, though, that Maximilian had an immediate stimulus for his "campaign of self-aggrandizement through public relation": the series of conflicts that involved Maximilian forced him to seek means to secure his position. Whaley further suggests that, despite the later religious divide, "patriotic motifs developed during Maximilian's reign, both by Maximilian himself and by the humanist writers who responded to him, formed the core of a national political culture."[64]

Maximilian's reign witnessed the gradual emergence of the German common language. His chancery played a notable role in developing new linguistic standards. Martin Luther credited Maximilian and the Wettin Elector Frederick the Wise with the unification of German language. Tennant and Johnson opine that while other chanceries have been considered significant and then receded in important when the research direction changes, the chanceries of these two rulers have always been considered important from the beginning. As a part of his influential literary and propaganda projects, Maximilian had his autobiographical works embellished, reworked and sometimes ghostwritten in the chancery itself. He is also credited with a major reform of the imperial chancery office: "Maximilian is said to have caused a standardization and streamlining in the language of his Chancery, which set the pace for chanceries and printers throughout the Empire."[159]

Architecture

Always short of money, Maximilian could not afford large scale building projects. However, he left a few notable constructions, among which the most remarkable is the cenotaph he began in the Hofkirche, Innsbruck, which was completed long after his death, and has been praised as the most important monument of Renaissance Austria[160] and considered the "culmination of Burgundian tomb tradition" (especially for the groups of statues of family members) that displayed Late Gothic features, combined with Renaissance traditions like reliefs and busts of Roman emperors.[161] The monument was vastly expanded under his son Ferdinand I, who added the tumba, the portal, and on the advice of his Vice Chancellor Georg Sigmund Seld, commissioned the 24 marble reliefs based on the images on the Triumphal Arch. The work was only finished under Archduke Ferdinand II (1529-1595).

After taking Tyrol, in order to symbolize his new wealth and power, he built the Golden Roof, the roof for a balcony overlooking the town center of Innsbruck, from which to watch the festivities celebrating his assumption of rule over Tyrol. The roof is made with gold-plated copper tiles. The structure was a symbol of the presence of the ruler, even when he was physically absent. It began the vogue of using reliefs to decorate oriel windows. The Golden Roof is also considered one of the most notable Habsburg monuments. Like Maximilian's cenotaph, it is in an essentially Gothic idiom.[162]

Modern postal system

Together with Franz von Taxis, in 1490, Maximilian developed the first modern postal service in the world. The system was originally built to improve communication between his scattered territories, connecting Burgundy, Austria, Spain and France and later developing to an Europe-wide, fee-based system. Fixed postal routes (the first in Europe) were developed, together with regular and reliable service. From the beginning of the sixteenth century, the system became open to private mail.[163][164]

The capital resources he poured into the postage system as well as support for the related printing press (when Archduke, he opened a school for sophisticated engraving techniques) were on a level unprecedented by European monarches, and earned him stern rebuke from the father.[165]

Political legacy

Maximilian had appointed his daughter Margaret as the Regent of the Netherlands, and she fulfilled this task well. Tupu Ylä-Anttila opines that Margaret acted as defacto queen consort in a political sense, first to her father and then Charles V, "absent rulers" who needed a representative dynastic presence that also complemented their characteristics. Her queenly virtues helped her to play the role of diplomat and peace-maker, as well as guardian and educator of future rulers, whom Maximilian called "our children" or "our common children" in letters to Margaret. This was a model that developed as part of the solution for the emerging Habsburg composite monarchy and would continue to serve later generations.[166]

Through wars and marriages he extended the Habsburg influence in every direction: to the Netherlands, Spain, Bohemia, Hungary, Poland, and Italy. This influence lasted for centuries and shaped much of European history. The Habsburg Empire survived as the Austro-Hungarian Empire until it was dissolved 3 November 1918 – 399 years 11 months and 9 days after the passing of Maximilian.

Geoffrey Parker summarizes Maximilian's political legacy as follows:[167]

By the time Charles received his presentation copy of Der Weisskunig in 1517, Maximilian could point to four major successes. He had protected and reorganized the Burgundian Netherlands, Whose political future had seemed bleak when he became their ruler forty years earlier. Likewise, he had overcome the obstacles posed by individual institutions, traditions and languages to forge the sub-Alpine lands he inherited from his father into a single state: ‘Austria’, ruled and taxed by a single administration that he created at Innsbruck. He had also reformed the chaotic central government of the Holy Roman Empire in ways that, though imperfect, would last almost until its demise three centuries later. Finally, by arranging strategic marriages for his grandchildren, he had established the House of Habsburg as the premier dynasty in central and eastern Europe, creating a polity that his successors would expand over the next four centuries.

The Britannica Encyclopaedia comments on Maximilian's achievements:[92]

Maximilian I [...] made his family, the Habsburgs, dominant in 16th-century Europe. He added vast lands to the traditional Austrian holdings, securing the Netherlands by his own marriage, Hungary and Bohemia by treaty and military pressure, and Spain and the Spanish empire by the marriage of his son Philip [...] Great as Maximilian’s achievements were, they did not match his ambitions; he had hoped to unite all of western Europe by reviving the empire of Charlemagne [...] His military talents were considerable and led him to use war to attain his ends. He carried out meaningful administrative reforms, and his military innovations would transform Europe’s battlefields for more than a century, but he was ignorant of economics and was financially unreliable.

Maximilian's life is still commemorated in Central Europe centuries later. The Order of St. George, which he sponsored, still exists.[168] In 2011, for example, a monument was erected for him in Cortina d’Ampezzo.[169] Also in 1981 in Cormons on the Piazza Liberta a statue of Maximilian, which was there until the First World War, was put up again.[170] On the occasion of the 500th anniversary of his death there were numerous commemorative events in 2019 at which Karl von Habsburg, the current head of the House of Habsburg, represented the imperial dynasty.[171][172][173]

Amsterdam still retains close ties with the emperor. He once came to the city as a pilgrim and recovered from an illness here. As the city supported him financially in his military expeditions, he granted its citizens the right to use the image of his crown, which remains a symbol of the city as part of its coat-of-arms. The practice survived the later revolt against Habsburg Spain.[174] The central canal in Amsterdam was named in 1615 as the Keizersgracht (Emperor's Canal) after Maximilian. The city beer (Brugse Zot, or The Fools of Bruges) of Bruges, which suffered a four century long decline that was partially inflicted by Maximilian's orders (that required foreign merchants to transfer operations to Antwerp – later he would withdraw the orders but it proved too late.)[175][176], is associated with the emperor, who according to legend told the city in a conciliatory celebration that they did not need to build an asylum, as the city was full of fools.[177] The swans of the city are considered a perpetual remembrance (allegedly ordered by Maximilian) for Lanchals (whose name meant "long necks" and whose emblem was a swan), the loyalist minister who got beheaded while Maximilian was forced to watch.[178] In Mechelen, Burgundian capital under Margaret of Austria, every 25 years, an ommegang that commemorates Maximilian's arrival as well as other major events is organized.[179]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Official style

-

Coat of arms of Maximilian I of Habsburg as Holy Roman Emperor

-

Coat of arms of Maximilian I of Habsburg as King of the Romans.

Maximilian I, by the grace of God elected Holy Roman Emperor, forever August, King of Germany, of Hungary, Dalmatia, Croatia, etc. Archduke of Austria, Duke of Burgundy, Brabant, Lorraine, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola, Limburg, Luxembourg, Gelderland, Landgrave of Alsace, Prince of Swabia, Count Palatine of Burgundy, Princely Count of Habsburg, Hainaut, Flanders, Tyrol, Gorizia, Artois, Holland, Seeland, Ferrette, Kyburg, Namur, Zutphen, Margrave of the Holy Roman Empire, the Enns, Burgau, Lord of Frisia, the Wendish March, Pordenone, Salins, Mechelen, etc. etc.[citation needed]

Chivalric orders

On 30 April 1478, Maximilian was knighted by Adolf of Cleves (1425-1492), a senior member of the Order of the Golden Fleece and on the same day he became the sovereign of this exalted order. As its head, he did everything in his power to restore its glory as well as associate the order with the Habsburg lineage. He expelled the members who had defected to France and rewarded those loyal to him, and also invited foreign rulers to join its ranks.[185]

Maximilian I was a member of the Order of the Garter, nominated by King Henry VII of England in 1489. His Garter stall plate survives in St George's Chapel, Windsor Castle.[186]

Appearance and personality

Maximilian was strongly built with an upright posture, had neck length blond or reddish hair, a large hooked nose and a jutting jaw (like his father, he always shaved his beard, as the jutting jaw was considered a noble feature).[187] Although not conventionally handsome, he was well-proportioned and in his youth was considered physically attractive, with an affable, pleasing manner.[188][189]