1804 Haitian massacre: Difference between revisions

Sangdeboeuf (talk | contribs) m Cleaned up 2 ISBNs using toolforge:anticompositetools/hyphenator #hyphenator, harmonize whitespace in citation templates by script |

Sangdeboeuf (talk | contribs) Merging duplicate refs, adding full citation(s) & full-text link(s), other misc. |

||

| Line 11: | Line 11: | ||

| perpetrators = Army of [[Jean-Jacques Dessalines]] |

| perpetrators = Army of [[Jean-Jacques Dessalines]] |

||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''1804 Haiti massacre''' was carried out against the remaining [[French people|French]] population in Haiti at the end of the [[Haitian Revolution]],<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/haitian-revolution-1791-1804/ |title=Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) |

The '''1804 Haiti massacre''' was carried out against the remaining [[French people|French]] population in Haiti at the end of the [[Haitian Revolution]],<ref>{{Cite web |last=Sutherland |first=Claudia |url=https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/haitian-revolution-1791-1804/ |title=Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) |date=16 July 2007 |website=Blackpast.org |access-date=17 June 2022}}</ref> by soldiers, mostly former slaves, under orders from [[Jean-Jacques Dessalines]]. |

||

From early January 1804 until 22 April 1804, squads of soldiers moved from house to house throughout Haiti, torturing and killing entire families.<ref name=" |

From early January 1804 until 22 April 1804, squads of soldiers moved from house to house throughout Haiti, torturing and killing entire families.<ref name="Danner p107">{{cite book |last=Danner |first=Mark |title=Stripping Bare the Body: Politics, Violence, War |date=2009 |publisher=Nation Books |location=New York |isbn=978-1-5685-8413-3 |page=107}}</ref> Between 3,000 and 5,000 people were killed.{{sfnp|Girard|2011|pp=319–322}} |

||

[[Nicholas A. Robins]] and [[Adam Jones (Canadian scholar)|Adam Jones]] theorize that the executions were a "genocide of the [[Subaltern (postcolonialism)|subaltern]]", in which an oppressed group uses [[Genocide|genocidal]] means to destroy its oppressors.{{r|Robins & Jones}} Other scholars{{Who|date=May 2022}} have suggested the threat of [[Haitian Revolution#Rebellion against reimposition of slavery|reinvasion and reinstatement of slavery]] as reasons for the massacre. |

[[Nicholas A. Robins]] and [[Adam Jones (Canadian scholar)|Adam Jones]] theorize that the executions were a "genocide of the [[Subaltern (postcolonialism)|subaltern]]", in which an oppressed group uses [[Genocide|genocidal]] means to destroy its oppressors.{{r|Robins & Jones}} Other scholars{{Who|date=May 2022}} have suggested the threat of [[Haitian Revolution#Rebellion against reimposition of slavery|reinvasion and reinstatement of slavery]] as reasons for the massacre.{{sfnp|Girard|2005a|pp=}} |

||

Throughout the early-to-mid nineteenth century, the events of the massacre were well known in the United States. Additionally, many [[Saint Dominicans|Saint Dominican]] refugees moved from Saint-Domingue to the U.S., settling in [[New Orleans]], [[Charleston, South Carolina|Charleston]], [[New York City|New York]], [[Baltimore]] and other coastal cities. These events spurred fears of potential uprisings in the [[Southern United States|Southern U.S.]] and they also polarized public opinion on the question of the abolition of slavery.<ref name=" |

Throughout the early-to-mid nineteenth century, the events of the massacre were well known in the United States. Additionally, many [[Saint Dominicans|Saint Dominican]] refugees moved from Saint-Domingue to the U.S., settling in [[New Orleans]], [[Charleston, South Carolina|Charleston]], [[New York City|New York]], [[Baltimore]] and other coastal cities. These events spurred fears of potential uprisings in the [[Southern United States|Southern U.S.]] and they also polarized public opinion on the question of the abolition of slavery.<ref name="Julius 2004">{{cite book |last1=Julius |first1=Kevin C. |title=The abolitionist decade, 1829-1838 : a year-by-year history of early events in the antislavery movement |date=2004 |publisher=McFarland & Co |location=Jefferson, N.C. |isbn=0-7864-1946-6}}{{Page needed|date=June 2022}}</ref><ref name="Marcotte p171">{{cite book |last1=Marcotte |first1=Frank B. |title=Six days in April : Lincoln and the Union in peril |date=2005 |publisher=Algora Publishing |location=New York |isbn=0-8758-6313-2 |page=171}}</ref> |

||

==Background== |

==Background== |

||

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

{{Further|Slavery in Haiti}} |

{{Further|Slavery in Haiti}} |

||

[[Henri Christophe]]'s personal secretary,<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.travelinghaiti.com/christophes-kingdom-petions-republic/ |title=Christophe's Kingdom and Pétion's Republic |date= |

[[Henri Christophe]]'s personal secretary,<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.travelinghaiti.com/christophes-kingdom-petions-republic/ |title=Christophe's Kingdom and Pétion's Republic |website=Travelinghaiti.com |access-date=17 June 2022}}</ref>{{Unreliable source?|reason=Self-published website|date=June 2022}} who was a slave for much of his life, attempted to explain the incident by referencing the cruel treatment of black slaves by white slaveholders in [[Saint-Domingue]]: |

||

<blockquote>Have they not [[hanging|hung up]] men with heads downward, [[drowning|drowned]] them in sacks, [[crucifixion|crucified]] them on planks, [[buried alive|buried them alive]], [[crushing (execution)|crushed]] them in mortars? Have they not forced them to [[Coprophagia|consume faeces]]? And, having [[flaying|flayed]] them with the lash, have they not cast them alive to be devoured by worms, or onto anthills, or lashed them to stakes in the swamp to be devoured by mosquitoes? Have they not [[boiling to death|thrown them into boiling cauldrons]] of [[Sugarcane|cane syrup]]? Have they not put men and women inside barrels studded with spikes and rolled them down mountainsides into the abyss? Have they not consigned these miserable blacks to man eating-dogs until the latter, sated by human flesh, left the mangled victims to be finished off with [[bayonet]] and poniard?<ref>{{cite book |title=Written in Blood: The Story of the Haitian People, 1492–1995 |last1=Heinl |first1= |

<blockquote>Have they not [[hanging|hung up]] men with heads downward, [[drowning|drowned]] them in sacks, [[crucifixion|crucified]] them on planks, [[buried alive|buried them alive]], [[crushing (execution)|crushed]] them in mortars? Have they not forced them to [[Coprophagia|consume faeces]]? And, having [[flaying|flayed]] them with the lash, have they not cast them alive to be devoured by worms, or onto anthills, or lashed them to stakes in the swamp to be devoured by mosquitoes? Have they not [[boiling to death|thrown them into boiling cauldrons]] of [[Sugarcane|cane syrup]]? Have they not put men and women inside barrels studded with spikes and rolled them down mountainsides into the abyss? Have they not consigned these miserable blacks to man eating-dogs until the latter, sated by human flesh, left the mangled victims to be finished off with [[bayonet]] and poniard?<ref>{{cite book |title=Written in Blood: The Story of the Haitian People, 1492–1995 |last1=Heinl |first1=Michael |last2=Heinl |first2=Robert Debs |last3=Heinl |first3=Nancy Gordon |year=2005 |edition=Revised |publisher=Univ. Press of America |location=Lanham, Md; London |isbn=0-7618-3177-0 |url-access=registration |url=https://archive.org/details/writteninbloodst00hein/page/n2/mode/1up?view=theater}}{{Page needed|date=June 2022}}</ref></blockquote> |

||

===Haitian Revolution=== |

===Haitian Revolution=== |

||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

[[File:Incendie de la Plaine du Cap. - Massacre des Blancs par les Noirs. FRANCE MILITAIRE. - Martinet del. - Masson Sculp - 33.jpg|thumb|250px|"Burning of the Plaine du Cap - Massacre of whites by the blacks." On August 22, 1791, slaves set fire to plantations, torched cities and massacred the white population.]] |

[[File:Incendie de la Plaine du Cap. - Massacre des Blancs par les Noirs. FRANCE MILITAIRE. - Martinet del. - Masson Sculp - 33.jpg|thumb|250px|"Burning of the Plaine du Cap - Massacre of whites by the blacks." On August 22, 1791, slaves set fire to plantations, torched cities and massacred the white population.]] |

||

In 1791, a man of Jamaican origin named [[Dutty Boukman]] became the leader of the enslaved Africans held on a large plantation in [[Cap-Français]].<ref name="Cheuse 2002">{{cite book |last=Cheuse |first=Alan |author-link=Alan Cheuse |title=Listening to the Page: Adventures in Reading and Writing |url=https://archive.org/details/listeningtopagea00cheu/page/58/mode/1up?view=theater |url-access=registration |date=2002 |publisher=Columbia University Press |isbn=978-0-231-12271-9 |pages=58–59}}</ref> In the wake of the [[French Revolution]], he planned to massacre all the French living in Cap-Français.<ref name="Cheuse 2002"/> On 22 August 1791, the enslaved Africans descended on Le Cap, where they destroyed the plantations and executed all the French who lived in the region.<ref name="Cheuse 2002"/> King [[Louis XVI]] was accused of indifference to the massacre, while the slaves seemed to think the king was on their side.<ref name=" |

In 1791, a man of Jamaican origin named [[Dutty Boukman]] became the leader of the enslaved Africans held on a large plantation in [[Cap-Français]].<ref name="Cheuse 2002">{{cite book |last=Cheuse |first=Alan |author-link=Alan Cheuse |title=Listening to the Page: Adventures in Reading and Writing |url=https://archive.org/details/listeningtopagea00cheu/page/58/mode/1up?view=theater |url-access=registration |date=2002 |publisher=Columbia University Press |isbn=978-0-231-12271-9 |pages=58–59}}</ref> In the wake of the [[French Revolution]], he planned to massacre all the French living in Cap-Français.<ref name="Cheuse 2002"/> On 22 August 1791, the enslaved Africans descended on Le Cap, where they destroyed the plantations and executed all the French who lived in the region.<ref name="Cheuse 2002"/> King [[Louis XVI]] was accused of indifference to the massacre, while the slaves seemed to think the king was on their side.<ref name="Douthwaite 2012">{{cite book |first=Julia V. |last=Douthwaite |title=The Frankenstein of 1790 and Other Lost Chapters from Revolutionary France |date=2012 |publisher=University of Chicago Press |isbn=978-0-226-16058-0 |page=110}}</ref> In July 1793, the French in [[Les Cayes]] were massacred.<ref name="Geggus 1989">{{cite book |last=Geggus |first=David |editor-first1=Franklin W. |editor-last1=Knight |editor-first2=Colin A. |editor-last2=Palmer |title=The Modern Caribbean |year=1989 |publisher=University of North Carolina Press |isbn=978-0-8078-4240-9 |page=32 |chapter=The Haitian Revolution |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/moderncaribbean0000unse/page/32/mode/1up?view=theater |chapter-url-access=registration}}</ref> |

||

Despite the French proclamation of emancipation, the blacks sided with the Spanish who came to occupy the region.<ref name="Popkin2010B">{{cite book |first=Jeremy D. |last=Popkin |title=Facing Racial Revolution: Eyewitness Accounts of the Haitian Insurrection |

Despite the French proclamation of emancipation, the blacks sided with the Spanish who came to occupy the region.<ref name="Popkin2010B">{{cite book |first=Jeremy D. |last=Popkin |title=Facing Racial Revolution: Eyewitness Accounts of the Haitian Insurrection |date=2007 |publisher=University of Chicago Press |isbn=978-0-226-67582-4 |page=252}}</ref> In July 1794, Spanish forces stood by while the black troops of [[Jean-François Papillon|Jean-François]] massacred the French whites in [[Fort-Liberté|Fort-Dauphin]].<ref name="Popkin2010B"/> |

||

Philippe Girard writes that [[genocide]] was openly considered as a strategy by both sides in the conflict.{{ |

Philippe Girard writes that [[genocide]] was openly considered as a strategy by both sides in the conflict.{{sfnp|Girard|2005a|loc=abstract}} White forces sent by [[Napoleon Bonaparte]] committed massacres but were defeated before they could accomplish genocide, while an army under [[Jean-Jacques Dessalines]], composed mainly of former slaves, was able to wipe out the white Haitian population.{{sfnp|Girard|2005a|loc=abstract}} Girard describes five main factors leading to the massacre, which he describes as a genocide: (1) Haitian soldiers were influenced by the French Revolution to justify murder and large-scale massacres on ideological grounds; (2) economic interests motivated French planters to want to quell the uprising, as well as influencing former slaves to want to kill the planters and take ownership of the plantations; (3) a slave revolt had been ongoing for more than a decade, and was itself a reaction to a century of brutal colonial rule, making violent death commonplace and therefore easier to accept; (4) the massacre was a form of [[class warfare]] in which former slaves were able to take revenge against their former masters; and (5) the last stages of the war became a racial conflict pitting Whites against Blacks and [[Mulatto]]es, in which racial hatred, dehumanization, and conspiracy theories all facilitated [[genocide]].{{sfnp|Girard|2005a|loc=abstract}} |

||

Dessalines came to power after France's defeat and subsequent evacuation from what was previously known as [[Saint-Domingue]]. In November 1803, three days after [[Donatien-Marie-Joseph de Vimeur, vicomte de Rochambeau|Rochambeau's]] forces surrendered, Dessalines ordered the execution of 800 French soldiers who had been left behind due to illness during the evacuation.{{ |

Dessalines came to power after France's defeat and subsequent evacuation from what was previously known as [[Saint-Domingue]]. In November 1803, three days after [[Donatien-Marie-Joseph de Vimeur, vicomte de Rochambeau|Rochambeau's]] forces surrendered, Dessalines ordered the execution of 800 French soldiers who had been left behind due to illness during the evacuation.{{sfnp|Popkin|2012|p=137}}{{sfnp|Girard|2011|p=319}} He did guarantee the safety of the remaining white civilian population.{{sfnp|Dayan|1998}}{{page needed|date=February 2012}}{{sfnp|Shen|2008}} However, Jeremy Popkin writes that statements by Dessalines such as "There are still French on the island, and still you considered yourselves free," spoke of a hostile attitude toward the remaining white minority.{{sfnp|Popkin|2012|p=137}} |

||

Rumors about the white population suggested that they would try to leave the country to convince foreign powers to invade and reintroduce slavery. Discussions between Dessalines and his advisers openly suggested that the white population should be put to death for the sake of national security. Whites trying to leave Haiti were prevented from doing so.{{ |

Rumors about the white population suggested that they would try to leave the country to convince foreign powers to invade and reintroduce slavery. Discussions between Dessalines and his advisers openly suggested that the white population should be put to death for the sake of national security. Whites trying to leave Haiti were prevented from doing so.{{sfnp|Girard|2011|p=319}} |

||

On 1 January 1804, Dessalines proclaimed Haiti an independent nation.{{ |

On 1 January 1804, Dessalines proclaimed Haiti an independent nation.{{sfnp|Dayan|1998|pp=3–4}} Dessalines later gave the order to all cities in Haiti that all [[white people|whites]] should be put to death.{{sfnp|Girard|2011|p=319}} The weapons used should be silent weapons such as knives and bayonets rather than gunfire, so that the killing could be done more quietly, and avoid warning intended victims by the sound of gunfire and thereby giving them the opportunity to escape.{{sfnp|Dayan|1998|p=4}} |

||

==Massacre== |

==Massacre== |

||

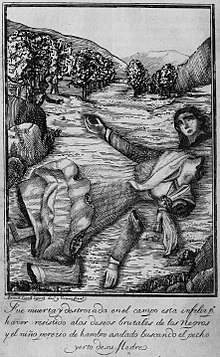

[[File:Manuel Lopez Lopez Iodibo - Desalines - Huyes del valor frances, pero matando blancos.jpg|thumb|250px|An 1806 engraving of [[Jean-Jacques Dessalines]]. It depicts the general, sword raised in one arm, while the other holds the severed head of a white woman.]] |

[[File:Manuel Lopez Lopez Iodibo - Desalines - Huyes del valor frances, pero matando blancos.jpg|thumb|250px|An 1806 engraving of [[Jean-Jacques Dessalines]]. It depicts the general, sword raised in one arm, while the other holds the severed head of a white woman.]] |

||

During February and March, Dessalines traveled among the cities of Haiti to assure himself that his orders were carried out. Despite his orders, the massacres were often not carried out until he visited the cities in person.{{ |

During February and March, Dessalines traveled among the cities of Haiti to assure himself that his orders were carried out. Despite his orders, the massacres were often not carried out until he visited the cities in person.{{sfnp|Popkin|2012|p=137}} |

||

The course of the massacre showed an almost identical pattern in every city he visited. Before his arrival, there were only a few killings, despite his orders.{{ |

The course of the massacre showed an almost identical pattern in every city he visited. Before his arrival, there were only a few killings, despite his orders.{{sfnp|Girard|2011|pp=321–322}} When Dessalines arrived, he first spoke about the atrocities committed by former white authorities, such as [[Donatien-Marie-Joseph de Vimeur, vicomte de Rochambeau|Rochambeau]] and [[Charles Leclerc (general, born 1772)|Leclerc]], after which he demanded that his orders about mass killings of the area's white population should be put into effect. Reportedly, he ordered the unwilling to take part in the killings, especially men of [[mixed race]], so that the blame should not be placed solely on the black population.{{sfnp|Dayan|1998|p={{page needed|date=February 2012}}}}{{sfnp|Girard|2011|p=321}} Mass killings took place on the streets and on places outside the cities. |

||

In parallel to the killings, plundering and [[rape]] also occurred.{{ |

In parallel to the killings, plundering and [[rape]] also occurred.{{sfnp|Girard|2011|p=321}} Women and children were generally killed last. White women were "often raped or pushed into [[forced marriage]]s under threat of death."{{sfnp|Girard|2011|p=321}} |

||

Dessalines did not specifically mention that the white women should be killed, and the soldiers were reportedly somewhat hesitant to do so. In the end, however, the women were also put to death, though normally at a later stage of the massacre than the adult males.{{ |

Dessalines did not specifically mention that the white women should be killed, and the soldiers were reportedly somewhat hesitant to do so. In the end, however, the women were also put to death, though normally at a later stage of the massacre than the adult males.{{sfnp|Girard|2011|pp=321–322}} The argument for killing the women was that whites would not truly be eradicated if the white women were spared to give birth to new Frenchmen.{{sfnp|Girard|2011|p=322}} |

||

Before his departure from a city, Dessalines would proclaim an amnesty for all the whites who had survived in hiding during the massacre. When these people left their hiding place however, most (French) were killed as well.{{ |

Before his departure from a city, Dessalines would proclaim an amnesty for all the whites who had survived in hiding during the massacre. When these people left their hiding place however, most (French) were killed as well.{{sfnp|Girard|2011|p=321}} Many{{how many|date=February 2018}} <!-- how many? -->whites were, however, hidden and smuggled out to sea by foreigners.{{sfnp|Girard|2011|p=321}} However, there were notable exceptions to the ordered killings. A contingent of [[Polish Legions (Napoleonic period)|Polish]] defectors were given amnesty and granted Haitian citizenship for their renouncement of French allegiance and support of Haitian independence. Dessalines referred to the Poles as ''"the White Negroes of Europe"'', as an expression of his solidarity and gratitude.<ref>{{cite book |first=Susan |last=Buck-Morss |title=Hegel, Haiti, and Universal History |year=2009 |publisher=University of Pittsburgh Press |isbn=978-0-8229-7334-8 |pages=75 ff}}</ref> |

||

In [[Port-au-Prince]], only a few killings had occurred in the city despite the orders. After Dessalines arrived on 18 March, the number of killings escalated. According to a merchant captain, about 800 people were killed in the city, while about 50 survived.{{ |

In [[Port-au-Prince]], only a few killings had occurred in the city despite the orders. After Dessalines arrived on 18 March, the number of killings escalated. According to a merchant captain, about 800 people were killed in the city, while about 50 survived.{{sfnp|Girard|2011|p=321}} On 18 April 1804, Dessalines arrived at [[Cap-Haïtien]]. Only a handful of killings had taken place there before his arrival, but the killings escalated to a massacre on the streets and outside the city after his arrival.{{sfnp|Girard|2011|p=321}} |

||

As elsewhere, the majority of the women were initially not killed. Dessalines's advisers, however, pointed out that the white Haitians would not disappear if the women were left to give birth to white men, and after this, Dessalines ordered that the women should be killed as well, with the exception of those who agreed to marry non-white men.{{ |

As elsewhere, the majority of the women were initially not killed. Dessalines's advisers, however, pointed out that the white Haitians would not disappear if the women were left to give birth to white men, and after this, Dessalines ordered that the women should be killed as well, with the exception of those who agreed to marry non-white men.{{sfnp|Girard|2011|pp=321–322}} Sources created at the time stated that 3,000 people were killed in Cap-Haïtien; Philippe Girard writes that this figure was unrealistic as in the post-evacuation of the French people the settlement had only 1,700 white people.{{sfnp|Girard|2011|p=321}} |

||

One of the most notorious of the massacre participants was Jean Zombi, a [[mulatto]] resident of Port-au-Prince who was known for his brutality. One account describes how Zombi stopped a white man on the street, stripped him naked, and took him to the stair of the Presidential Palace, where he killed him with a dagger. Dessalines was reportedly among the spectators; he was said to be "horrified" by the episode.{{ |

One of the most notorious of the massacre participants was Jean Zombi, a [[mulatto]] resident of Port-au-Prince who was known for his brutality. One account describes how Zombi stopped a white man on the street, stripped him naked, and took him to the stair of the Presidential Palace, where he killed him with a dagger. Dessalines was reportedly among the spectators; he was said to be "horrified" by the episode.{{sfnp|Dayan|1998|p=36}} In [[Haitian Vodou]] tradition, the figure of Jean Zombi has become a prototype for the [[zombie]].{{sfnp|Dayan|1998|pp=35–38}}{{contradict inline|Zombie}} |

||

==Aftermath== |

==Aftermath== |

||

===Effects in Haiti=== |

===Effects in Haiti=== |

||

By the end of April 1804, some 3,000 to 5,000 people had been killed{{ |

By the end of April 1804, some 3,000 to 5,000 people had been killed{{sfnp|Girard|2011|p=322}} and the white Haitians were practically eradicated, excluding a select group of whites who were given amnesty. The spared consisted of the [[Polish_Haitians#History|Polish ex-soldiers]] who were given Haitian citizenship for helping black Haitians in fights against white colonialists; a small group of German colonists invited to the [[Nord-Ouest (department)|north-west region]] before the revolution; and a group of medical doctors and professionals.{{sfnp|Popkin|2012|p=137}} Reportedly, also people with connections to officers in the Haitian army were spared, as well as the women who agreed to marry non-white men.{{sfnp|Girard|2011|p=322}} |

||

Dessalines did not try to hide the massacre from the world. In an official proclamation of 8 April 1804, he stated, "We have given these true cannibals war for war, crime for crime, outrage for outrage. Yes, I have saved my country, I have avenged [[Americas|America]]."{{ |

Dessalines did not try to hide the massacre from the world. In an official proclamation of 8 April 1804, he stated, "We have given these true cannibals war for war, crime for crime, outrage for outrage. Yes, I have saved my country, I have avenged [[Americas|America]]."{{sfnp|Popkin|2012|p=137}} He referred to the massacre as an act of national authority. Dessalines regarded the elimination of the white Haitians an act of political necessity, as they were regarded as a threat to the peace between the black and the free people of color. It was also regarded as a necessary act of vengeance.{{sfnp|Girard|2011|p=322}} Dessalines' secretary [[Boisrond-Tonnerre]] stated, "For our declaration of independence, we should have the skin of a white man for parchment, his skull for an inkwell, his blood for ink, and a bayonet for a pen!"<ref name="haiti">[http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/r?frd/cstdy:@field(DOCID+ht0019) Independent Haiti], [[Library of Congress Country Studies]].</ref> |

||

Dessalines was eager to assure that Haiti was not a threat to other nations. He directed efforts to establish friendly relations also to nations where slavery was still allowed.{{ |

Dessalines was eager to assure that Haiti was not a threat to other nations. He directed efforts to establish friendly relations also to nations where slavery was still allowed.{{sfnp|Girard|2011|p=326}} |

||

In the 1805 constitution, all citizens were defined as "black".{{ |

In the 1805 constitution, all citizens were defined as "black".{{sfnp|Girard|2011|p=325}} The constitution also banned white men from owning land, except for people already born or born in the future to white women who were naturalized as Haitian citizens and the Germans and Poles who got Haitian citizenship.{{sfnp|Girard|2011|p=322}}{{sfnp|1805 Constitution of Haiti}} The massacre had a long-lasting effect on the view of the [[Haitian Revolution]]. It helped to create a legacy of racial hostility in Haitian society.{{sfnp|Girard|2011|p=325}} |

||

Girard writes in |

Girard writes in his book ''Paradise Lost'': "Despite all of Dessalines' efforts at rationalization, the massacres were as inexcusable as they were foolish."{{sfnp|Girard|2005b|p=56}} Trinidadian historian [[C. L. R. James]] concurred with this view in his breakthrough work ''[[The Black Jacobins]]'', writing that "the unfortunate country... was ruined economically, its population lacking in social culture, [and] had its difficulties doubled by this massacre". James wrote that the massacre was "not policy but revenge, and revenge has no place in politics".<ref name="James p373">{{cite book |last1=James |first1=C. L. R. |title=The Black Jacobins; Toussaint L'Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution |date=1989 |orig-date=First published 1938 |publisher=Vintage Books |location=New York |pages=373-374 |isbn=0-679-72467-2 |edition=2nd |url=https://archive.org/details/blackjacobinstou00jame/page/373/mode/1up?view=theater |url-access=registration}}</ref> |

||

Philippe Girard writes "when the genocide was over, Haiti's white population was virtually non-existent."{{ |

Philippe Girard writes "when the genocide was over, Haiti's white population was virtually non-existent."{{sfnp|Girard|2005a}}{{Page needed|date=June 2022}} Citing Girard, Nicholas A. Robins and [[Adam Jones (Canadian scholar)|Adam Jones]] describe the massacre as a "genocide of the [[Subaltern (postcolonialism)|subaltern]]" in which a previously disadvantaged group used a genocide to destroy their previous oppressors.<ref name="Robins & Jones">{{cite book |editor1-last=Robins |editor1-first=Nicholas A. |editor2-first=Adam |editor2-last=Jones |title=Genocides by the Oppressed: Subaltern Genocide in Theory and Practice |publisher=Indiana University Press |date=2009 |isbn=978-0-2532-2077-6 |page=3 |quote=The Great Rebellion and the Haitian slave uprising are two examples of what we refer to as 'subaltern genocide': cases in which subaltern actors—those objectively oppressed and disempowered—adopt genocidal strategies to vanquish their oppressors.}} {{block indent|left=1|See also: {{cite book |last1=Jones |first1=Adam |chapter=Subaltern genocide: Genocides by the oppressed |title=The Scourge of Genocide: Essays and Reflections |publisher=Routledge |date=2013 |isbn=978-1-1350-4715-3 |page=169 |others=With Nicholas Robins}} }}</ref> |

||

===Effect on American society=== |

===Effect on American society=== |

||

{{Further|Abolitionism in the United States}} |

{{Further|Abolitionism in the United States}} |

||

At the time of the [[American Civil War|U.S. Civil War]], a major pretext for [[Southern United States|Southern whites]], most of whom did not own slaves, to support slave-owners (and ultimately fight for the [[Confederate States of America|Confederacy]]) was fear of a genocide similar to the Haitian Massacre of 1804.{{Citation needed|date=July 2021}} The failed experiments in Haiti and Jamaica were explicitly referred to in Confederate discourse as a reason for secession.<ref> |

At the time of the [[American Civil War|U.S. Civil War]], a major pretext for [[Southern United States|Southern whites]], most of whom did not own slaves, to support slave-owners (and ultimately fight for the [[Confederate States of America|Confederacy]]) was fear of a genocide similar to the Haitian Massacre of 1804.{{Citation needed|date=July 2021}} The failed experiments in Haiti and Jamaica were explicitly referred to in Confederate discourse as a reason for secession.<ref name="McCurry p12">{{cite book |last1=McCurry |first1=Stephanie |title=Confederate Reckoning: Power and Politics in the Civil War South |date=2010 |publisher=Harvard University Press |location=Cambridge, Mass. |isbn=978-0-6740-4589-7 |pages=12–13}}</ref> |

||

The slave revolt was a prominent theme in the discourse of southern political leaders and had influenced U.S. public opinion since the events took place. Historian Kevin C. Julius writes: |

The slave revolt was a prominent theme in the discourse of southern political leaders and had influenced U.S. public opinion since the events took place. Historian [[Kevin C. Julius]] writes: |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | In the run-up to the [[1860 United States presidential election|U.S. presidential election of 1860]], [[Roger B. Taney]], [[Chief Justice of the United States|Chief Justice]] of the [[United States Supreme Court|Supreme Court]], wrote "I remember the horrors of St. Domingo" and said that the election "will determine whether anything like this is to be visited upon our own southern countrymen."<ref name=" |

||

| ⚫ | In the run-up to the [[1860 United States presidential election|U.S. presidential election of 1860]], [[Roger B. Taney]], [[Chief Justice of the United States|Chief Justice]] of the [[United States Supreme Court|Supreme Court]], wrote "I remember the horrors of St. Domingo" and said that the election "will determine whether anything like this is to be visited upon our own southern countrymen."<ref name="Marcotte p171"/> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | {{Quote|We don't know any better than to imagine that emancipation would result in the utter extinction of civilization in the South, because the slave-holders, and those in their interest, have persistently told us ... and they always instance the |

||

| ⚫ | {{Quote|We don't know any better than to imagine that emancipation would result in the utter extinction of civilization in the South, because the slave-holders, and those in their interest, have persistently told us ... and they always instance the 'horrors of St. Domingo.'<ref name="Lyon 1861">{{cite news |last1=Lyon |first1=J. B. |title=What Shall be Done with the Slaves? |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1861/09/06/archives/what-shall-be-done-with-the-slaves.html |work=The New York Times |date=6 September 1861 |issn=0362-4331 |page=2 |url-access=limited}}</ref>}} |

||

Lyon argued, however, that the abolition of slavery in the various Caribbean colonies of the European empires before the 1860s showed that an end to slavery could be achieved peacefully. |

Lyon argued, however, that the abolition of slavery in the various Caribbean colonies of the European empires before the 1860s showed that an end to slavery could be achieved peacefully. |

||

| Line 99: | Line 100: | ||

==References== |

==References== |

||

* {{cite book |first=Joan |last=Dayan |year=1998 |title=Haiti, History, and the Gods |publisher=University of California Press |isbn=978-0-520-21368-5}} |

* {{cite book |first=Joan |last=Dayan |year=1998 |title=Haiti, History, and the Gods |publisher=University of California Press |isbn=978-0-520-21368-5}} |

||

| ⚫ | * {{cite journal |last=Girard |first=Philippe |title=Caribbean genocide: racial war in Haiti, 1802–4 |journal=[[Patterns of Prejudice]] |date=2005a |volume=39 |issue=2: Colonial Genocide |pages=138–161 |doi=10.1080/00313220500106196 |s2cid=145204936}} {{block indent|left=1|Reprinted in: {{Cite book |editor1-last=Moses |editor1-first=Dirk |editor2-last=Stone |editor2-first=Dan |title=Colonialism and Genocide. |date=2013 |publisher=Taylor and Francis |isbn=978-1-317-99753-5 |location=Hoboken |pages=42–65}} }} |

||

* {{cite book |last1=Girard |first1=Philippe R. |title=Paradise Lost: Haiti’s Tumultuous Journey from Pearl of the Caribbean to Third World Hot Spot |date=2005b |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan |isbn=978-1-4039-8031-1 |page=56 |doi=10.1057/9781403980311_4 |chapter=Missed Opportunities: Haiti after Independence (1804–1915)}} |

|||

* {{cite book |first=Philippe R. |last=Girard |year=2011 |title=The Slaves Who Defeated Napoleon: Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian War of Independence 1801–1804 |location=Tuscaloosa, Alabama |publisher=The University of Alabama Press |isbn=978-0-8173-1732-4}} |

* {{cite book |first=Philippe R. |last=Girard |year=2011 |title=The Slaves Who Defeated Napoleon: Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian War of Independence 1801–1804 |location=Tuscaloosa, Alabama |publisher=The University of Alabama Press |isbn=978-0-8173-1732-4}} |

||

| ⚫ | * {{cite journal |last=Girard |first=Philippe |title=Caribbean genocide: racial war in Haiti, 1802–4 |journal=[[Patterns of Prejudice]] | |

||

* {{cite book |first=Jeremy D. |last=Popkin |year=2012 |title=A Concise History of the Haitian Revolution |location=Chicester, West Sussex |publisher=Wiley-Blackwell |isbn=978-1-4051-9820-2}} |

* {{cite book |first=Jeremy D. |last=Popkin |year=2012 |title=A Concise History of the Haitian Revolution |location=Chicester, West Sussex |publisher=Wiley-Blackwell |isbn=978-1-4051-9820-2}} |

||

* {{cite web |first=Kona |last=Shen |url=http://library.brown.edu/haitihistory/11.html | |

* {{cite web |first=Kona |last=Shen |url=http://library.brown.edu/haitihistory/11.html |work=History of Haiti, 1492–1805 |title=Haitian Independence, 1804–1805 |publisher=Brown University, Department of Africana Studies |date=December 9, 2008 |access-date=1 February 2012}} |

||

* {{cite web |url=http://www.webster.edu/~corbetre/haiti/history/earlyhaiti/1805-const.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20051228150910/http://www.webster.edu/~corbetre/haiti/history/earlyhaiti/1805-const.htm |archive-date=28 December 2005 |title=The 1805 Constitution of Haiti | |

* {{cite web |url=http://www.webster.edu/~corbetre/haiti/history/earlyhaiti/1805-const.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20051228150910/http://www.webster.edu/~corbetre/haiti/history/earlyhaiti/1805-const.htm |archive-date=28 December 2005 |title=The 1805 Constitution of Haiti |via=Webster University |date=10 December 2011 |ref={{sfnpRef|1805 Constitution of Haiti}} |url-status=dead |postscript=. (Transcribed by Bob Corbett. This document is an English translation published in the ''New York Evening Post'' on July 15, 1805. This version does not include Articles 40–44. Corbett states that [[Henri Christophe]], due to his affinity for English and his involvement with the publication, may have been the translator.)}} |

||

==Further reading== |

==Further reading== |

||

| ⚫ | |||

* {{cite journal |last=Girard |first=Philippe R. |url=https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00313220500106196?journalCode=rpop20 |title=Caribbean genocide: racial war in Haiti, 1802–4 |journal=[[Patterns of Prejudice]] |volume=39 |issue=2: Colonial Genocide |year=2005 |pages=138–161 |doi=10.1080/00313220500106196 |s2cid=145204936 |ref=none}} |

|||

* {{cite web |title=A Brief History of Dessalines from 1825 Missionary Journal |url=http://faculty.webster.edu/corbetre/haiti/history/earlyhaiti/dessalines.htm |website=faculty.webster.edu}} |

|||

| ⚫ | * {{cite journal |author=Popkin, Jeremy D. |title=A Survivor of Dessalines's Massacres in 1804 |journal=Facing Racial Revolution: Eyewitness Accounts of the Haitian Insurrection |year=2008 |doi=10.7208/chicago/9780226675855.001.0001 |isbn=978-0-226-67583-1}} |

||

==External links== |

|||

* [http://faculty.webster.edu/corbetre/haiti/history/earlyhaiti/dessalines.htm A Brief History of Dessalines], from American Missionary Register, October 1825 |

|||

{{coord missing|Haiti}} |

{{coord missing|Haiti}} |

||

Revision as of 20:16, 17 June 2022

| 1804 Haiti massacre | |

|---|---|

| Part of the aftermath of the Haitian Revolution | |

Engraving depicting a killing during the massacre | |

| Location | First Empire of Haiti |

| Date | January 1804 – 22 April 1804 |

| Target | French people |

| Deaths | 3,000–5,000 |

| Perpetrators | Army of Jean-Jacques Dessalines |

The 1804 Haiti massacre was carried out against the remaining French population in Haiti at the end of the Haitian Revolution,[1] by soldiers, mostly former slaves, under orders from Jean-Jacques Dessalines. From early January 1804 until 22 April 1804, squads of soldiers moved from house to house throughout Haiti, torturing and killing entire families.[2] Between 3,000 and 5,000 people were killed.[3]

Nicholas A. Robins and Adam Jones theorize that the executions were a "genocide of the subaltern", in which an oppressed group uses genocidal means to destroy its oppressors.[4] Other scholars[who?] have suggested the threat of reinvasion and reinstatement of slavery as reasons for the massacre.[5]

Throughout the early-to-mid nineteenth century, the events of the massacre were well known in the United States. Additionally, many Saint Dominican refugees moved from Saint-Domingue to the U.S., settling in New Orleans, Charleston, New York, Baltimore and other coastal cities. These events spurred fears of potential uprisings in the Southern U.S. and they also polarized public opinion on the question of the abolition of slavery.[6][7]

Background

Slavery

Henri Christophe's personal secretary,[8][unreliable source?] who was a slave for much of his life, attempted to explain the incident by referencing the cruel treatment of black slaves by white slaveholders in Saint-Domingue:

Have they not hung up men with heads downward, drowned them in sacks, crucified them on planks, buried them alive, crushed them in mortars? Have they not forced them to consume faeces? And, having flayed them with the lash, have they not cast them alive to be devoured by worms, or onto anthills, or lashed them to stakes in the swamp to be devoured by mosquitoes? Have they not thrown them into boiling cauldrons of cane syrup? Have they not put men and women inside barrels studded with spikes and rolled them down mountainsides into the abyss? Have they not consigned these miserable blacks to man eating-dogs until the latter, sated by human flesh, left the mangled victims to be finished off with bayonet and poniard?[9]

Haitian Revolution

In 1791, a man of Jamaican origin named Dutty Boukman became the leader of the enslaved Africans held on a large plantation in Cap-Français.[10] In the wake of the French Revolution, he planned to massacre all the French living in Cap-Français.[10] On 22 August 1791, the enslaved Africans descended on Le Cap, where they destroyed the plantations and executed all the French who lived in the region.[10] King Louis XVI was accused of indifference to the massacre, while the slaves seemed to think the king was on their side.[11] In July 1793, the French in Les Cayes were massacred.[12]

Despite the French proclamation of emancipation, the blacks sided with the Spanish who came to occupy the region.[13] In July 1794, Spanish forces stood by while the black troops of Jean-François massacred the French whites in Fort-Dauphin.[13]

Philippe Girard writes that genocide was openly considered as a strategy by both sides in the conflict.[14] White forces sent by Napoleon Bonaparte committed massacres but were defeated before they could accomplish genocide, while an army under Jean-Jacques Dessalines, composed mainly of former slaves, was able to wipe out the white Haitian population.[14] Girard describes five main factors leading to the massacre, which he describes as a genocide: (1) Haitian soldiers were influenced by the French Revolution to justify murder and large-scale massacres on ideological grounds; (2) economic interests motivated French planters to want to quell the uprising, as well as influencing former slaves to want to kill the planters and take ownership of the plantations; (3) a slave revolt had been ongoing for more than a decade, and was itself a reaction to a century of brutal colonial rule, making violent death commonplace and therefore easier to accept; (4) the massacre was a form of class warfare in which former slaves were able to take revenge against their former masters; and (5) the last stages of the war became a racial conflict pitting Whites against Blacks and Mulattoes, in which racial hatred, dehumanization, and conspiracy theories all facilitated genocide.[14]

Dessalines came to power after France's defeat and subsequent evacuation from what was previously known as Saint-Domingue. In November 1803, three days after Rochambeau's forces surrendered, Dessalines ordered the execution of 800 French soldiers who had been left behind due to illness during the evacuation.[15][16] He did guarantee the safety of the remaining white civilian population.[17][page needed][18] However, Jeremy Popkin writes that statements by Dessalines such as "There are still French on the island, and still you considered yourselves free," spoke of a hostile attitude toward the remaining white minority.[15]

Rumors about the white population suggested that they would try to leave the country to convince foreign powers to invade and reintroduce slavery. Discussions between Dessalines and his advisers openly suggested that the white population should be put to death for the sake of national security. Whites trying to leave Haiti were prevented from doing so.[16]

On 1 January 1804, Dessalines proclaimed Haiti an independent nation.[19] Dessalines later gave the order to all cities in Haiti that all whites should be put to death.[16] The weapons used should be silent weapons such as knives and bayonets rather than gunfire, so that the killing could be done more quietly, and avoid warning intended victims by the sound of gunfire and thereby giving them the opportunity to escape.[20]

Massacre

During February and March, Dessalines traveled among the cities of Haiti to assure himself that his orders were carried out. Despite his orders, the massacres were often not carried out until he visited the cities in person.[15]

The course of the massacre showed an almost identical pattern in every city he visited. Before his arrival, there were only a few killings, despite his orders.[21] When Dessalines arrived, he first spoke about the atrocities committed by former white authorities, such as Rochambeau and Leclerc, after which he demanded that his orders about mass killings of the area's white population should be put into effect. Reportedly, he ordered the unwilling to take part in the killings, especially men of mixed race, so that the blame should not be placed solely on the black population.[22][23] Mass killings took place on the streets and on places outside the cities.

In parallel to the killings, plundering and rape also occurred.[23] Women and children were generally killed last. White women were "often raped or pushed into forced marriages under threat of death."[23]

Dessalines did not specifically mention that the white women should be killed, and the soldiers were reportedly somewhat hesitant to do so. In the end, however, the women were also put to death, though normally at a later stage of the massacre than the adult males.[21] The argument for killing the women was that whites would not truly be eradicated if the white women were spared to give birth to new Frenchmen.[24]

Before his departure from a city, Dessalines would proclaim an amnesty for all the whites who had survived in hiding during the massacre. When these people left their hiding place however, most (French) were killed as well.[23] Many[quantify] whites were, however, hidden and smuggled out to sea by foreigners.[23] However, there were notable exceptions to the ordered killings. A contingent of Polish defectors were given amnesty and granted Haitian citizenship for their renouncement of French allegiance and support of Haitian independence. Dessalines referred to the Poles as "the White Negroes of Europe", as an expression of his solidarity and gratitude.[25]

In Port-au-Prince, only a few killings had occurred in the city despite the orders. After Dessalines arrived on 18 March, the number of killings escalated. According to a merchant captain, about 800 people were killed in the city, while about 50 survived.[23] On 18 April 1804, Dessalines arrived at Cap-Haïtien. Only a handful of killings had taken place there before his arrival, but the killings escalated to a massacre on the streets and outside the city after his arrival.[23]

As elsewhere, the majority of the women were initially not killed. Dessalines's advisers, however, pointed out that the white Haitians would not disappear if the women were left to give birth to white men, and after this, Dessalines ordered that the women should be killed as well, with the exception of those who agreed to marry non-white men.[21] Sources created at the time stated that 3,000 people were killed in Cap-Haïtien; Philippe Girard writes that this figure was unrealistic as in the post-evacuation of the French people the settlement had only 1,700 white people.[23]

One of the most notorious of the massacre participants was Jean Zombi, a mulatto resident of Port-au-Prince who was known for his brutality. One account describes how Zombi stopped a white man on the street, stripped him naked, and took him to the stair of the Presidential Palace, where he killed him with a dagger. Dessalines was reportedly among the spectators; he was said to be "horrified" by the episode.[26] In Haitian Vodou tradition, the figure of Jean Zombi has become a prototype for the zombie.[27][contradictory]

Aftermath

Effects in Haiti

By the end of April 1804, some 3,000 to 5,000 people had been killed[24] and the white Haitians were practically eradicated, excluding a select group of whites who were given amnesty. The spared consisted of the Polish ex-soldiers who were given Haitian citizenship for helping black Haitians in fights against white colonialists; a small group of German colonists invited to the north-west region before the revolution; and a group of medical doctors and professionals.[15] Reportedly, also people with connections to officers in the Haitian army were spared, as well as the women who agreed to marry non-white men.[24]

Dessalines did not try to hide the massacre from the world. In an official proclamation of 8 April 1804, he stated, "We have given these true cannibals war for war, crime for crime, outrage for outrage. Yes, I have saved my country, I have avenged America."[15] He referred to the massacre as an act of national authority. Dessalines regarded the elimination of the white Haitians an act of political necessity, as they were regarded as a threat to the peace between the black and the free people of color. It was also regarded as a necessary act of vengeance.[24] Dessalines' secretary Boisrond-Tonnerre stated, "For our declaration of independence, we should have the skin of a white man for parchment, his skull for an inkwell, his blood for ink, and a bayonet for a pen!"[28]

Dessalines was eager to assure that Haiti was not a threat to other nations. He directed efforts to establish friendly relations also to nations where slavery was still allowed.[29]

In the 1805 constitution, all citizens were defined as "black".[30] The constitution also banned white men from owning land, except for people already born or born in the future to white women who were naturalized as Haitian citizens and the Germans and Poles who got Haitian citizenship.[24][31] The massacre had a long-lasting effect on the view of the Haitian Revolution. It helped to create a legacy of racial hostility in Haitian society.[30]

Girard writes in his book Paradise Lost: "Despite all of Dessalines' efforts at rationalization, the massacres were as inexcusable as they were foolish."[32] Trinidadian historian C. L. R. James concurred with this view in his breakthrough work The Black Jacobins, writing that "the unfortunate country... was ruined economically, its population lacking in social culture, [and] had its difficulties doubled by this massacre". James wrote that the massacre was "not policy but revenge, and revenge has no place in politics".[33]

Philippe Girard writes "when the genocide was over, Haiti's white population was virtually non-existent."[5][page needed] Citing Girard, Nicholas A. Robins and Adam Jones describe the massacre as a "genocide of the subaltern" in which a previously disadvantaged group used a genocide to destroy their previous oppressors.[4]

Effect on American society

At the time of the U.S. Civil War, a major pretext for Southern whites, most of whom did not own slaves, to support slave-owners (and ultimately fight for the Confederacy) was fear of a genocide similar to the Haitian Massacre of 1804.[citation needed] The failed experiments in Haiti and Jamaica were explicitly referred to in Confederate discourse as a reason for secession.[34] The slave revolt was a prominent theme in the discourse of southern political leaders and had influenced U.S. public opinion since the events took place. Historian Kevin C. Julius writes:

As abolitionists loudly proclaimed that "All men are created equal", echoes of armed slave insurrections and racial genocide sounded in Southern ears. Much of their resentment towards the abolitionists can be seen as a reaction to the events in Haiti.[6]

In the run-up to the U.S. presidential election of 1860, Roger B. Taney, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, wrote "I remember the horrors of St. Domingo" and said that the election "will determine whether anything like this is to be visited upon our own southern countrymen."[7]

Abolitionists recognized the strength of this argument on public opinion in both the north and south. In correspondence to the New York Times in September 1861 (during the war), an abolitionist named J. B. Lyon addressed this as a prominent argument of his opponents:

We don't know any better than to imagine that emancipation would result in the utter extinction of civilization in the South, because the slave-holders, and those in their interest, have persistently told us ... and they always instance the 'horrors of St. Domingo.'[35]

Lyon argued, however, that the abolition of slavery in the various Caribbean colonies of the European empires before the 1860s showed that an end to slavery could be achieved peacefully.

See also

Notes

- ^ Sutherland, Claudia (16 July 2007). "Haitian Revolution (1791-1804)". Blackpast.org. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ Danner, Mark (2009). Stripping Bare the Body: Politics, Violence, War. New York: Nation Books. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-5685-8413-3.

- ^ Girard (2011), pp. 319–322.

- ^ a b Robins, Nicholas A.; Jones, Adam, eds. (2009). Genocides by the Oppressed: Subaltern Genocide in Theory and Practice. Indiana University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-2532-2077-6.

The Great Rebellion and the Haitian slave uprising are two examples of what we refer to as 'subaltern genocide': cases in which subaltern actors—those objectively oppressed and disempowered—adopt genocidal strategies to vanquish their oppressors.

See also: Jones, Adam (2013). "Subaltern genocide: Genocides by the oppressed". The Scourge of Genocide: Essays and Reflections. With Nicholas Robins. Routledge. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-1350-4715-3. - ^ a b Girard (2005a).

- ^ a b Julius, Kevin C. (2004). The abolitionist decade, 1829-1838 : a year-by-year history of early events in the antislavery movement. Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland & Co. ISBN 0-7864-1946-6.[page needed]

- ^ a b Marcotte, Frank B. (2005). Six days in April : Lincoln and the Union in peril. New York: Algora Publishing. p. 171. ISBN 0-8758-6313-2.

- ^ "Christophe's Kingdom and Pétion's Republic". Travelinghaiti.com. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ Heinl, Michael; Heinl, Robert Debs; Heinl, Nancy Gordon (2005). Written in Blood: The Story of the Haitian People, 1492–1995 (Revised ed.). Lanham, Md; London: Univ. Press of America. ISBN 0-7618-3177-0.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Cheuse, Alan (2002). Listening to the Page: Adventures in Reading and Writing. Columbia University Press. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-0-231-12271-9.

- ^ Douthwaite, Julia V. (2012). The Frankenstein of 1790 and Other Lost Chapters from Revolutionary France. University of Chicago Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-226-16058-0.

- ^ Geggus, David (1989). "The Haitian Revolution". In Knight, Franklin W.; Palmer, Colin A. (eds.). The Modern Caribbean. University of North Carolina Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-8078-4240-9.

- ^ a b Popkin, Jeremy D. (2007). Facing Racial Revolution: Eyewitness Accounts of the Haitian Insurrection. University of Chicago Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-226-67582-4.

- ^ a b c Girard (2005a), abstract.

- ^ a b c d e Popkin (2012), p. 137.

- ^ a b c Girard (2011), p. 319.

- ^ Dayan (1998).

- ^ Shen (2008).

- ^ Dayan (1998), pp. 3–4.

- ^ Dayan (1998), p. 4.

- ^ a b c Girard (2011), pp. 321–322.

- ^ Dayan (1998), p. [page needed].

- ^ a b c d e f g h Girard (2011), p. 321.

- ^ a b c d e Girard (2011), p. 322.

- ^ Buck-Morss, Susan (2009). Hegel, Haiti, and Universal History. University of Pittsburgh Press. pp. 75 ff. ISBN 978-0-8229-7334-8.

- ^ Dayan (1998), p. 36.

- ^ Dayan (1998), pp. 35–38.

- ^ Independent Haiti, Library of Congress Country Studies.

- ^ Girard (2011), p. 326.

- ^ a b Girard (2011), p. 325.

- ^ 1805 Constitution of Haiti.

- ^ Girard (2005b), p. 56.

- ^ James, C. L. R. (1989) [First published 1938]. The Black Jacobins; Toussaint L'Ouverture and the San Domingo Revolution (2nd ed.). New York: Vintage Books. pp. 373–374. ISBN 0-679-72467-2.

- ^ McCurry, Stephanie (2010). Confederate Reckoning: Power and Politics in the Civil War South. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-6740-4589-7.

- ^ Lyon, J. B. (6 September 1861). "What Shall be Done with the Slaves?". The New York Times. p. 2. ISSN 0362-4331.

References

- Dayan, Joan (1998). Haiti, History, and the Gods. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-21368-5.

- Girard, Philippe (2005a). "Caribbean genocide: racial war in Haiti, 1802–4". Patterns of Prejudice. 39 (2: Colonial Genocide): 138–161. doi:10.1080/00313220500106196. S2CID 145204936. Reprinted in: Moses, Dirk; Stone, Dan, eds. (2013). Colonialism and Genocide. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. pp. 42–65. ISBN 978-1-317-99753-5.

- Girard, Philippe R. (2005b). "Missed Opportunities: Haiti after Independence (1804–1915)". Paradise Lost: Haiti’s Tumultuous Journey from Pearl of the Caribbean to Third World Hot Spot. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 56. doi:10.1057/9781403980311_4. ISBN 978-1-4039-8031-1.

- Girard, Philippe R. (2011). The Slaves Who Defeated Napoleon: Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian War of Independence 1801–1804. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-1732-4.

- Popkin, Jeremy D. (2012). A Concise History of the Haitian Revolution. Chicester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-9820-2.

- Shen, Kona (December 9, 2008). "Haitian Independence, 1804–1805". History of Haiti, 1492–1805. Brown University, Department of Africana Studies. Retrieved 1 February 2012.

- "The 1805 Constitution of Haiti". 10 December 2011. Archived from the original on 28 December 2005 – via Webster University. (Transcribed by Bob Corbett. This document is an English translation published in the New York Evening Post on July 15, 1805. This version does not include Articles 40–44. Corbett states that Henri Christophe, due to his affinity for English and his involvement with the publication, may have been the translator.)

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link)

Further reading

- Popkin, Jeremy D. (2008). "A Survivor of Dessalines's Massacres in 1804". Facing Racial Revolution: Eyewitness Accounts of the Haitian Insurrection. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226675855.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-226-67583-1.

- "A Brief History of Dessalines from 1825 Missionary Journal". faculty.webster.edu.