Benicia, California

Benicia, California | |

|---|---|

| City of Benicia | |

|

Top: Benicia Capitol (left), Portuguese Hall of Benicia (right); middle: view from the Carquinez Strait; bottom: Benicia Arsenal Clocktower (left), Downtown Benicia (middle), Old Arsenal Blacksmith. | |

| Motto: "It's better in Benicia!" | |

Location of Benicia in Solano County, California | |

| Coordinates: 38°3′48″N 122°9′22″W / 38.06333°N 122.15611°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Solano |

| Incorporated | March 27, 1850[1] |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Steve Young[2] |

| • State senator | Bill Dodd (D)[3] |

| • Assemblymember | Buffy Wicks (D)[3] |

| • U. S. rep. | Tom McClintock (R)[4] |

| Area | |

• Total | 14.12 sq mi (36.57 km2) |

| • Land | 12.81 sq mi (33.19 km2) |

| • Water | 1.31 sq mi (3.39 km2) 17.75% |

| Elevation | 26 ft (8 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 27,131 |

| • Density | 2,117.46/sq mi (817.56/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Code | 94510 |

| Area code | 707 |

| FIPS code | 06-05290 |

| GNIS feature IDs | 0277472, 2409833 |

| Website | www |

Benicia (/bəˈniːʃə/ bə-NEE-shə, Spanish: [beˈnisja]) is a waterside city in Solano County, California, located in the North Bay region of the San Francisco Bay Area. It served as the capital of California for nearly thirteen months from 1853 to 1854. The population was 26,997 at the 2010 United States Census. The city is located along the north bank of the Carquinez Strait. Benicia is just east of Vallejo and across the strait from Martinez. Steve Young, elected in November 2020, is the mayor.

History

The City of Benicia was founded on May 19, 1847, by Dr. Robert Semple,[7] Thomas O. Larkin, and Comandante General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, on land sold to them by General Vallejo in December 1846. It was named for the General's wife, Francisca Benicia Carillo de Vallejo, a member of the Carrillo family of California, a prominent Californio dynasty. The General intended that the city be named "Francisca" after his wife, but this name was dropped when the former city of "Yerba Buena" changed its name to "San Francisco," so her second given name was used instead. In his memoirs, William Tecumseh Sherman contended that Benicia was "the best natural site for a commercial city" in the region.[8]

In February 1848, first word of gold found at Sutter's Mill was leaked at a Benicia Tavern, thus starting the California Gold Rush.[9][10][11] Benicia became a way station on the way to the Sierras.[12]

In March 1850, Benicia became one of the first incorporated cities in California, a month after Sacramento.[13] Benicia was the original county seat of Solano County. The lower floor of the Benicia Masonic Hall, built in 1850 with lumber donated by Benicia founder Robert Semple on land donated by Alexander Riddell, was used as the County court room and offices prior to the completion of Benicia's city hall.[14] In 1858, the county seat was moved to Fairfield.

In 1853, Benicia became the third site selected to serve as the California State capital, after San Jose and nearby Vallejo, and its newly constructed city hall was California's capitol from February 11, 1853, to February 25, 1854. Soon after, the legislature was moved to the courthouse in Sacramento, which has remained the State capital ever since. The restored capitol is part of the Benicia Capitol State Historic Park, and is the only building remaining of the State's pre-Sacramento capitols.[13]

The original campus of Mills College was founded in Benicia in 1852 as the Young Ladies Seminary, and was the first women's college west of the Rocky Mountains. Before moving to Oakland in 1871, it was located on West I Street, just north of First Street.

From 1860 to 1861, Benicia was indirectly involved in the Pony Express. When riders missed their connection with a steamer in Sacramento, they would continue on to Benicia and cross over to Martinez via the ferry.[15] One of the earliest companies in California, the Pacific Mail Steamship Company, established a major shipyard in Benicia in the 19th century. The prolific shipbuilder Matthew Turner formed the Matthew Turner Shipyard at Benicia in 1883. Benicia became an important wheat storage and shipping site. It was also the site of the United States Army's Benicia Arsenal.

On December 1, 1879, the Central Pacific Railroad rerouted the Sacramento-Oakland portion of its transcontinental line to Benicia and established a major railroad ferry across the Carquinez Strait from Benicia to Port Costa. The world's largest ferry, the Solano, later joined by the even larger Contra Costa, carried entire trains across the Carquinez Strait from Benicia to Port Costa, from whence they continued on to the Oakland Pier.[16]

On June 5, 1889, the legendary prize fight between James J. Corbett and Joe Choynski was held on a barge off the coast of Benicia. The match lasted 28 rounds, and is now commemorated by a plaque near Southampton Bay.

Modern era

In 1901, the world's first long-distance powerline crossing over Carquinez Strait was built. After California's wheat output dropped in the early 20th century and especially after the Southern Pacific (which took over the operations of the Central Pacific) opened a railroad bridge to Martinez on October 15, 1930, eliminating the ferry crossing and the Benicia station, Benicia declined until the economic boom of World War II, in which the population doubled to about 7,000 residents.

A major fire on March 22, 1945, destroyed a half-block of businesses, including the nearly-century-old “old brewery”, and the Solano Hotel, with flames briefly threatening the old state capitol, now a historical landmark. A roof fire was quickly extinguished and the structure was not badly damaged. Losses were estimated at $125,000.[17]

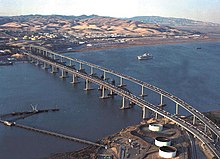

Two developments in the early 1960s would completely change Benicia: The closing of the Benicia Arsenal in 1960–64, and the completion of the Benicia–Martinez Bridge in 1962. The closing of the Arsenal removed Benicia's traditional economic base, but allowed city leaders to create an industrial park on Arsenal land which eventually provided more revenue for the city than the Army had. The completion of the Benicia-Martinez Bridge made it possible for the city to become a suburb of San Francisco and Oakland, and suburban development in the Benicia hills began in the late 1960s.

On December 20, 1968, near the Benicia water pumping station on Lake Herman Road, the Zodiac Killer made his debut by killing Vallejo natives David Faraday and Betty Lou Jensen as they rested or "necked" in Faraday's car. Near the same area on July 4 of the following year, the killer struck again, killing Darlene Elizabeth Ferrin and injuring Michael Mageau at the Blue Rock Springs Park in Vallejo, immediately next to Benicia.

Northeast of the town's residential areas an oil refinery was built and completed in 1969 by Humble Oil (later Exxon Corporation). The refinery was later bought by Valero Energy Corporation, a San Antonio-based oil company, in 2000.

Between 1970 and 1995, the population of Benicia grew steadily at a rate of about 1,000 people per year, and the city changed from a poor, blue-collar town of 7,000 to a white-collar bedroom suburb of 27,000.

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 15.7 square miles (41 km2), of which 12.9 square miles (33 km2) are land and 2.8 square miles (7.3 km2), comprising 17.75%, are water. Benicia is located on the north side of the Carquinez Strait.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 1,794 | — | |

| 1890 | 2,361 | 31.6% | |

| 1900 | 2,751 | 16.5% | |

| 1910 | 2,360 | −14.2% | |

| 1920 | 2,693 | 14.1% | |

| 1930 | 2,913 | 8.2% | |

| 1940 | 2,419 | −17.0% | |

| 1950 | 7,284 | 201.1% | |

| 1960 | 6,070 | −16.7% | |

| 1970 | 7,349 | 21.1% | |

| 1980 | 15,376 | 109.2% | |

| 1990 | 24,437 | 58.9% | |

| 2000 | 26,865 | 9.9% | |

| 2010 | 26,997 | 0.5% | |

| 2020 | 27,131 | 0.5% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[18] | |||

2010

The 2010 United States Census[19] reported that Benicia had a population of 26,997. The population density was 1,717.4 inhabitants per square mile (663.1/km2). The racial makeup of Benicia was 19,568 (72.5%) White, 1,510 (5.6%) African American, 135 (0.5%) Native American, 2,989 (11.1%) Asian, 102 (0.4%) Pacific Islander, 895 (3.3%) from other races, and 1,798 (6.7%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3,248 persons (12.0%).

The Census reported that 99.9% of the population lived in households and 0.1% lived in non-institutionalized group quarters.

There were 10,686 households, out of which 3,617 (33.8%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 5,668 (53.0%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 1,271 (11.9%) had a female householder with no husband present, 480 (4.5%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 584 (5.5%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 102 (1.0%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 2,628 households (24.6%) were made up of individuals, and 893 (8.4%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.52. There were 7,419 families (69.4% of all households); the average family size was 3.02.

The population was spread out, with 6,317 people (23.4%) under the age of 18, 1,923 people (7.1%) aged 18 to 24, 6,087 people (22.5%) aged 25 to 44, 9,303 people (34.5%) aged 45 to 64, and 3,367 people (12.5%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42.9 years. For every 100 females, there were 92.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.9 males.

There were 11,306 housing units at an average density of 719.2 per square mile (277.7/km2), of which 70.5% were owner-occupied and 29.5% were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 2.0%; the rental vacancy rate was 6.1%. 72.2% of the population lived in owner-occupied housing units and 27.7% lived in rental housing units.

2000

As of the census[20] of 2000, there were 26,865 people, 10,328 households, and 7,239 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,082.6 inhabitants per square mile (804.1/km2). There were 10,547 housing units at an average density of 817.6 per square mile (315.7/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 78.89% White, 9.02% of the population were Hispanic or Latino, 7.56% Asian, 4.82% Black or African American, 0.60% Native American, 0.29% Pacific Islander, 2.65% from other races, and 5.18% from two or more races.

There were 10,328 households, out of which 36.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 54.2% were married couples living together, 11.9% had a female householder with no husband present, and 29.9% were non-families. 23.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 6.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.60 and the average family size was 3.10.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 27.1% under the age of 18, 6.5% from 18 to 24, 28.3% from 25 to 44, 28.8% from 45 to 64, and 9.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females, there were 94.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 90.1 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $67,617, and the median income for a family was $77,974 (these figures had risen to $84,025 and $102,889 respectively as of a 2007 estimate[21]). Males had a median income of $59,628 versus $39,893 for females. The per capita income for the city was $31,226. About 3.1% of families and 4.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 4.4% of those under age 18 and 2.9% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

Top employers

According to the city's 2011 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[22] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Valero | 516 |

| 2 | Benicia Unified School District | 465 |

| 3 | Dunlop Manufacturing | 248 |

| 4 | City of Benicia | 229 |

| 5 | CytoSport | 221 |

| 6 | Bio-Rad Laboratories | 209 |

| 7 | Coca-Cola Refreshments | 162 |

| 8 | Valley Fine Foods | 133 |

| 9 | Pepsi Beverages Company | 119 |

| 10 | 1-800 Radiator & A/C | 106 |

Arts and culture

Arts Benicia is a community-based non-profit organization whose mission is to stimulate, educate, and nurture cultural life in Benicia primarily through the visual arts. They provide exhibitions, educational programs, and classes that support artists and engage the broader community. The organization offers dynamic year-round art exhibitions and public art openings, the Benicia Artists Open Studios event in the spring, the Annual Benefit Art Auction in the fall, various special projects, and quarterly art classes for adults and kids. It is located in the Benicia Arsenal at the Commanding Officer’s Quarters at 1 Commandant's Lane.[23] Gallery hours are Thursday-Sunday, 12:00-5:00 PM during exhibitions; gallery admission is free to the public.[24]

Arts in the Park is an annual summer art celebration held in Benicia City Park.[25] The Benicia Peddler's Fair is one of the largest street fairs in Northern California, this outdoor event began in 1963 with a few collectable and antique stores displaying their items on tables outside St. Paul's Church.[26] Traditionally held on the July 3, Benicia's Fourth of July parade stretches all the way down First Street and typically includes music, dancing, floats, horses, clowns, and live entertainment.

On the fourth Sunday in July, the Portuguese community in Benicia celebrates the feast of the Holy Ghost, continuing a devotion established by the Queen St. Isabel of Portugal, who was noted for her care for the poor. The festival starts with a parade to St. Dominic's Church followed by Mass, followed by an auction and a dance. The Holy Ghost Parade celebrated its centennial in Benicia in 2007.[27]

Benicia is an active sailing community. In addition to individual sailing out of the Benicia Marina, there are several organized events and competitions. During the summer months, there is a yacht racing competition on Thursday evenings sponsored by the Benicia Yacht Club. The Yacht Club co-sponsors the annual Jazz Cup regatta with the South Beach Yacht Club, and also sponsors a Youth Sailing Program that offers extensive training.

Education

The Benicia Unified School District operates the city's public schools.

- Elementary

- Matthew Turner Elementary School (named after a famous local shipbuilder)

- Robert Semple Elementary School (named after one of the city's founders)

- Mary Farmar Elementary School

- Joe Henderson Elementary School (named after a local educator and school superintendent)

- Middle schools

- Benicia Middle School[28]

- High schools

Transportation

Benicia has no rail transit, but offers bus transportation through SolTrans and SolanoExpress. The Benicia–Martinez Bridge provides an automobile and rail link over Carquinez Strait, as well as bicycle and pedestrian lanes which opened in August 2009.[29] Two blocks from the main downtown district, the Benicia Marina is a full-service marina, offering a fuel dock, pump-out station, launch ramp, general store, laundry, restrooms and showers.[30]

Notable people

Artists and designers

- Robert Arneson (1930–1992), sculptor, and professor of ceramics in the Art Department at UC Davis.

- Linda Fleming (born 1945), sculptor, and professor of art at CCA.

- Addison Mizner (1872–1933), visionary resort architect, born in Benicia.

- Manuel Neri (1930-2021), sculptor, has had a studio in Benicia since 1965.

- Guillermo Wagner Granizo (1923–1995), ceramic tile muralist, moved to Benicia in 1980.

Politics

- Serranus Clinton Hastings, U.S. Congressman and founder of the Hastings College of the Law at University of California[31]

- Lansing Mizner, Solano County judge and president of the California Senate

Sports

- Austin Carr, NFL football player

- John C. Heenan, boxer, aka "The Benicia Boy"

- Willie Calhoun, professional baseball player for the San Francisco Giants

Writers

- Stephen Vincent Benét, author of "The Devil and Daniel Webster" and other stories and poems, lived in the Arsenal as a young boy

- James Lloyd Breck, Episcopalian priest

- Jack London, author, worked in the local fishing industry, and began writing while living in Benicia

- Wilson Mizner, playwright, born in Benicia

- Elsie Robinson (1883–1956), American journalist, poet, memoirist, and short story writer, known for her syndicated Hearst column “Listen, World!”, born in Benicia

Sister city

Benicia has one sister city.[32]

– Tula de Allende, Hidalgo, Mexico

– Tula de Allende, Hidalgo, Mexico

Gallery

-

First Street in Benicia

-

St. Paul's Episcopal Church on First Street

-

The Majestic theater on First Street

-

Former California capitol

-

Bookshop Benicia on First Street

-

First Street Green and Mount Diablo

-

The Carquinez Strait

-

End of First Street, looking toward the Carquinez Strait

-

View of Mount Diablo

-

Union Hotel

-

Community garden

-

Houses in a neighborhood

-

A house on July 3, 2013

-

Benicia Community Center

-

United States Postal Service post office

-

Benicia City Hall

-

Benicia Public Library entrance

-

Benicia Public Library

-

Welcome sign

See also

References

- ^ "California Cities by Incorporation Date". California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Archived from the original (Word) on November 3, 2014. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ^ "City Council". City of Benicia. Retrieved September 20, 2021.

- ^ a b "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ "California's 5th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ "Benicia". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ Virtual Museum of the City of San Francisco Archived April 15, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Sherman, William Tecumseh (2011-11-21). The Memoirs of General W.T. Sherman: All Volumes (Illustrated) (Kindle Locations 1333). Kindle Edition.

- ^ Delaplane, Kristin (February 18, 1996). "Hotels flourished during Gold Rush period". solanohistory.net. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

It was in von Pfister's hotel that the first word of the discovery of gold was leaked. Charley Bennett, Sutter's courier, stopped in at the bar on his way to Monterey with news of the gold strike. After a few drinks, he let the cat out of the bag, telling one and all about the gold "in them thar hills."

- ^ Nolte, Carl (June 21, 1998). "THE SAN FRANCISCO '48ERS". SFgate.com. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

[Sutter] tried to get the lease recorded with General Mason, the American military governor of California. He sent a trusted messenger, a man named Charles Bennett, to Monterey with a pouch of gold and a letter confirming his deal with the Culumahs. Bennett was to tell no one but the governor about the gold. But Bennett stopped off at Benicia on the way to Monterey. At the town's only hotel and tavern, he heard a man talking about coal discoveries in what is now Contra Costa County. Bennett scoffed at coal; opened his pouch. Never mind coal, he said, look at this -- and out on the tavern bar he rolled nuggets of pure gold.

- ^ WEILENMAN, Donna Beth (August 26, 2015). "Von Pfister general store placed on National Register: One of city's first buildings earns long-sought designation". benicia herald online. Retrieved May 21, 2021.

- ^ "History".

- ^ a b "Benicia's Historical Buildings". benicialibrary.org. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- ^ "NRHP Nomination Form: Old Masonic Hall". npgallery.nps.gov. 1972. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- ^ "1860 to 1861 – The Pony Express". Benicia Historical Museum. Archived from the original on May 18, 2007. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Harris, Robert L. "The Railroad Ferry Steamer "Solano" Archived July 21, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. American Society of Civil Engineers, "Transactions" Vol XXII, April, 1890.

- ^ Associated Press, “Historic State Capital Saved - Benicia Loses Famed 100-Year-Old Brewery”, The San Bernardino Daily Sun, San Bernardino, California, Friday 23 March 1945, Volume 51, page 2.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA – Benicia city". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 14, 2016. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ Bureau, U.S. Census. "American FactFinder – Community Facts". census.gov. Archived from the original on February 10, 2020. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "City of Benicia CAFR" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 26, 2013. Retrieved February 25, 2012.

- ^ "Home". artsbenicia.org.

- ^ "Arts Benicia". artsbenicia.org. Archived from the original on April 1, 2015. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Benicia Peddlers Fair ~ Since 1963". beniciapeddlersfair.org. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ^ "B.D.E.S. Benicia Holy Ghost Society". beniciaholyghost.org. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ^ "Benicia Middle School: Home Page". schoolloop.com. Archived from the original on April 29, 2015. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ^ "District 4 – Benicia-Martinez Bridge". ca.gov. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ^ Benicia Marina Archived June 8, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "HASTINGS, Serranus Clinton, (1813 – 1893)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Archived from the original on June 8, 2007. Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 7, 2017. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

External links

- Benicia, California

- Cities in Solano County, California

- Carquinez Strait

- Former state capitals in the United States

- Incorporated cities and towns in California

- Glass beaches

- Populated places established in 1850

- 1850 establishments in California

- Cities in the San Francisco Bay Area

- Populated coastal places in California