Loincloth

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

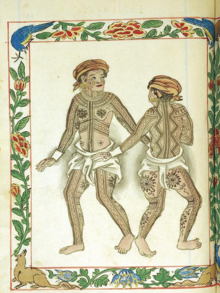

Sketch of a loincloth | |

| Type | Clothing that covers the genitals and sometimes the buttocks |

|---|---|

A loincloth is a one-piece garment, either wrapped around itself or kept in place by a belt. It covers the genitals and sometimes the buttocks. Loincloths which are held up by belts or strings are specifically known as breechcloth or breechclout.[1][2] Often, the flaps hang down in front and back.[2]

History and types

[edit]

Loincloths are worn in societies where no other clothing is needed or wanted. Loincloths are commonly used as an undergarment or swimsuit by wrestlers and by farmers in paddy fields in both Sri Lanka and India, where it is called Kovanam in Tamil, ambudaya in Sinhala and kaupinam or langot.

The loincloth, or breechcloth, is a basic form of dress, often worn as the only garment. Men have worn a loincloth as a fundamental piece of clothing which covers their genitals, not the buttocks, in most societies which disapproved of genital nakedness throughout human history. The loincloth is in essence a piece of material, bark-bast, leather, or cloth, passed between the legs and covering the genitals. Despite its functional simplicity, the loincloth comes in many different forms.

The styles in which breechcloths and loincloths can be arranged are myriad. Both the Bornean sirat and the Indian dhoti have fabric pass between the legs to support a man's genitals.

A similar style of loincloth was also characteristic of ancient Mesoamerica. The male inhabitants of the area of modern Mexico wore a wound loincloth of woven fabric. One end of the loincloth was held up, the remainder passed between the thighs, wound about the waist, and secured in back by tucking.[Note 1]

In Pre-Columbian South America, ancient Inca men wore a strip of cloth between their legs held up by strings or tape as a belt. The cloth was secured to the tapes at the back and the front portion hung in front as an apron, always well ornamented.[citation needed] The same garment,[citation needed] mostly in plain cotton but whose aprons are now, like T-shirts, sometimes decorated with logos, is known in Japan as etchu fundoshi.

Some of the culturally diverse Amazonian indigenous still wear an ancestral type of loincloth.[citation needed]

Until World War II, Japanese men wore a loincloth known as a fundoshi.[3] The fundoshi is a 35-centimetre-wide (14 in) piece of fabric (cotton or silk) passed between the thighs and secured to cover the genitals.[citation needed]

Loincloths by culture

[edit]Australia

[edit]

Worn by adult males in some Aboriginal cultures. Called naga, narga, nargar (etc) from Yulparija dialect of the Western Desert.[4]

India

[edit]Unsewn Kaupinam and its later-era sewn variation langot are traditional clothes in India, worn as underwear in dangal held in akharas especially wrestling, to prevent hernias and hydrocele.[5] Kacchera is mandatory for Sikhs to wear.

Japan

[edit]Japanese men and women traditionally wore a loincloth known as a fundoshi. The fundoshi is a 35 cm (14 in.) wide piece of fabric (cotton or silk) passed between the thighs and secured to cover the genitals. There are many ways of tying the fundoshi.[6]

Native American

[edit]

In most Native American tribes, men used to wear some form of breechcloth, often with leggings.[2][7][8][9] The style differed from tribe to tribe. In many tribes, the flaps hung down in front and back; in others, the breechcloth looped outside the belt and was tucked into the inside, for a more fitted look.[2] Sometimes, the breechcloth was much shorter, and a decorated apron panel was attached in front and behind.[2]

A Native American woman or teenage girl might also wear a fitted breechcloth underneath her skirt, but not as outerwear. However, in many tribes' young girls did wear breechcloths like the boys until they became old enough for skirts and dresses.[2] Among the Mohave people of the American Southwest, a breechcloth given to a young female symbolically recognizes her status as hwame.[10]

Philippines

[edit]

In the Philippines, loincloths of any sort are generally called bahág. It is often a single, long, rectangular cloth that is not tied with a belt or string and were made from either barkcloth or hand-woven textiles. The design of the weave is often unique to a specific tribe, while colors may denote the wearer’s social rank, such as plain white for commoners.[11]

Throughout the pre-colonial period, the bahág was the normative dress for commoners and the servile class (the alipin caste).[12] It survives today among some indigenous tribes of the Philippines, most notably the various Cordilleran peoples in the mountains of inland northern Luzon.[13]

The bahág was also favoured by the pre-colonial noble (tumao) and warrior (timawa) classes of the Visayan people, as it showed off their elaborate, full-body tattoos (batok) that advertised combat prowess and other significant achievements:[14][15]

The principal clothing of the Cebuanos and all the Visayans is the tattooing of which we have already spoken, with which a naked man appears to be dressed in a kind of handsome armor engraved with very fine work, a dress so esteemed by them they take it for their proudest attire, covering their bodies neither more nor less than a Christ crucified, so that although for solemn occasions they have the marlotas (robes) we mentioned, their dress at home and in their barrio is their tattoos and a bahag, as they call that cloth they wrap around their waist, which is the sort the ancient actors and gladiators used in Rome for decency's sake.

— Pedro Chirino, Relación de las Islas Filipinas (1604), [14]

One method of wrapping the bahág involves first pulling the long rectangular cloth (usually around 2 to 3 m (6 ft 7 in to 9 ft 10 in)) in between the legs to cover the genitals, with a longer back flap. This back flap is then twisted across the right leg, then crossed at the waist in an anti-clockwise direction. It then goes under the front flap, then across the left leg. It is twisted back across the back loop, above the buttocks. The result is the two rectangular ends hanging in front of and behind the waist, with a loop around the legs resembling a belt.

The native Tagalog word for "rainbow", bahagharì, literally means "loincloth of the king".[16]

Europe

[edit]

Some European men around 2000 BCE wore leather breechcloths, as can be seen from the clothing of Ötzi.[17] Ancient Romans wore a type of loincloth known as a subligaculum.

The use of breechcloths took on common use by the Metis and Acadians and are mentioned as early as the 1650s. In the 1740s and 50s they were issued to the Canadien as part of their war uniform and in 1755 they even tried to issue them to soldiers from France.

During their travels across Canada, the French [canadiens] dress as the Indians; they do not wear breeches. Many nations imitate the French customs; yet I observed, on the contrary, that the French in Canada, in many respects, follow the customs of the Indians, with whom they converse everyday. They make use of the tobacco pipes, shoes, garters, and girdles of the Indians.

— -Peter Kalm, 1749.

Those who go to war receive a capot, two cotton shirts, one breechclout, one pair of leggings, one blanket, one pair of souliers de boeuf, a wood-handled knife, a worm and a musket when they do not bring any. The breechclout is a piece of broadcloth draped between the thighs in the Native manner and with the two ends held by a belt. One wears it without breeches to walk more easily in the woods.

— d’Aleyrac, 1755–60.

During the week the men went about in their homes dressed much like the Indians, namely, in stockings and shoes like theirs, with garters, and a girdle about the waist; otherwise the clothing was like that of other Frenchmen.

— Kalm, p. 558

The French familiarized themselves with us, Studied our Tongue, and Manners, wore our Dress, Married our Daughters, and our Sons their Maids

— Pontiac, Ottawa leader, 2.2.50-57

See also

[edit]- Similar Indian clothes

- Related Indian clothes

- Similar garments

- Breechcloth

- Fundoshi

- Loincloth

- Mawashi

- Perizoma

- Subligaculum

- Thong

- Perizoma (loincloth)

- Fundoshi

- Kaupinam

- Related garments

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved on 2009-12-22.

- ^ a b c d e f Native Languages Archived 2009-07-02 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 2009-12-22.

- ^ Arita, Eriko (2009-05-10). "Fundoshi: undercover revolution". The Japan Times.

- ^ W. S. Ramson, ed. (1988). The Australian National Dictionary (1988 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 417. ISBN 0195547365.

- ^ Raman Das Mahatyagi (2007). Yatan Yoga: A Natural Guide to Health and Harmony. Yatan Ayurvedics. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-0-9803761-0-4.

- ^ "BOKUNAN-DO". www.shop-japan.co.jp.

- ^ Minor, Marz & Minor, Nono (1977). The American Indian Craft Book. Bison Books. pp. 72–73. ISBN 0-8032-5891-7. Google Book Search. Retrieved on 2010-07-15.

- ^ Mayfield, Thomas Jefferson (1997). Adopted by Indians: A True Story. Heyday Books. p. 83. ISBN 0-930588-93-2. Google Book Search. Retrieved on 2010-07-15.

- ^ Typical Indian Clothing (male). Retrieved on 2010-07-15.

- ^ Conner, Sparks, and Sparks, eds. (1997) Cassell's Encyclopedia of Queer Myth, Symbol, and Spirit: Covering Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Lore

- ^ Belen, Yvonne (21 June 2014). "Loincloth (G-string, Bahag)". Grand Cañao. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Lopez, Mellie Leandicho (2006). A Handbook of Philippine Folklore. UP Press. p. 385. ISBN 9789715425148.

- ^ Dalton, David; Keeling, Stephen (2013). The Rough Guide to the Philippines. Rough Guides UK. ISBN 9781405392075.

- ^ a b Scott, William Henry (1994). Barangay: Sixteenth-century Philippine Culture and Society. Ateneo University Press. pp. 20–27. ISBN 9789715501354.

- ^ Francia, Luis H. (2013). History of the Philippines: From Indios Bravos to Filipinos. Abrams. ISBN 978-1-4683-1545-5.

- ^ "Glossary of Confusing Pinoy Expressions". Spot.ph. 10 October 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology. Retrieved 2010-07-15.