Knitted fabric

Knitted fabric is a textile that results from knitting, the process of inter-looping of yarns or inter-meshing of loops. Its properties are distinct from woven fabric in that it is more flexible and can be more readily constructed into smaller pieces, making it ideal for socks and hats.

Weft-knit and warp-knit fabric

There are two basic varieties of knit fabric: weft-knit and warp-knit fabric.[1] Warp-knitted fabrics such as tricot and milanese are resistant to runs, and are commonly used in lingerie.

Weft-knit fabrics are easier to make and more common. When cut, they will unravel (run) unless repaired.

Warp-knit fabrics are resistant to runs and relatively easy to sew. Raschel lace—the most common type of machine made lace—is a warp knit fabric but using many more guide-bars (12+) than the usual machines which mostly have three or four bars. (14+)

Structure of knitted fabrics

Courses and wales

In weaving, threads are always straight, running parallel either lengthwise (warp threads) or crosswise (weft threads). By contrast, the yarn in knitted fabrics follows a meandering path (a course), forming symmetric loops (also called bights) symmetrically above and below the mean path of the yarn. These meandering loops can be easily stretched in different directions giving knit fabrics much more elasticity than woven fabrics. Depending on the yarn and knitting pattern, knitted garments can stretch as much as 500%. For this reason, knitting is believed to have been developed for garments that must be elastic or stretch in response to the wearer's motions, such as socks and hosiery. For comparison, woven garments stretch mainly along one or other of a related pair of directions that lie roughly diagonally between the warp and the weft, while contracting in the other direction of the pair (stretching and contracting with the bias), and are not very elastic, unless they are woven from stretchable material such as spandex. Knitted garments are often more form-fitting than woven garments, since their elasticity allows them to contour to the body's outline more closely; by contrast, curvature is introduced into most woven garments only with sewn darts, flares, gussets and gores, the seams of which lower the elasticity of the woven fabric still further. Extra curvature can be introduced into knitted garments without seams, as in the heel of a sock; the effect of darts, flares, etc. can be obtained with short rows or by increasing or decreasing the number of stitches. Thread used in weaving is usually much finer than the yarn used in knitting, which can give the knitted fabric more bulk and less drape than a woven fabric.

If they are not secured, the loops of a knitted course will come undone when their yarn is pulled; this is known as ripping out, unravelling knitting, or humorously, frogging (because you 'rip it', this sounds like a frog croaking: 'rib-bit').[2] To secure a stitch, at least one new loop is passed through it. Although the new stitch is itself unsecured ("active" or "live"), it secures the stitch(es) suspended from it. A sequence of stitches in which each stitch is suspended from the next is called a wale.[3] To secure the initial stitches of a knitted fabric, a method for casting on is used; to secure the final stitches in a wale, one uses a method of binding/casting off. During knitting, the active stitches are secured mechanically, either from individual hooks (in knitting machines) or from a knitting needle or frame in hand-knitting.

Knitting stitches and stitch patterns

Different stitches and stitch combinations affect the properties of knitted fabric. Individual stitches look differently; knit stitches look like "V"'s stacked vertically, whereas purl stitches look like a wavy horizontal line across the fabric. Patterns and pictures can be created using colors in knitted fabrics by using stitches as "pixels"; however, such pixels are usually rectangular, rather than square. Individual stitches, or rows of stitches, may be made taller by drawing more yarn into the new loop (an elongated stitch), which is the basis for uneven knitting: a row of tall stitches may alternate with one or more rows of short stitches for an interesting visual effect. Short and tall stitches may also alternate within a row, forming a fish-like oval pattern.

Stitches also affect the physical properties of a fabric. Stockinette stitch forms a smooth nap. Aran knitting patterns are used to create a bulkier fabric to retain heat.

In the simplest knitted fabric pattern, all the stitches are knit or purl; this is known as a garter stitch. Alternating rows of knit stitches and purl stitches produce what is known as a stockinette pattern/stocking stitch. Vertical stripes (ribbing) are possible by having alternating wales of knit and purl stitches. For example, a common choice is 2x2 ribbing, in which two wales of knit stitches are followed by two wales of purl stitches, etc. Horizontal striping (welting) is also possible, by alternating rows of knit and purl stitches. Checkerboard patterns (basketweave) are also possible, the smallest of which is known as seed/moss stitch: the stitches alternate between knit and purl in every wale and along every row.

Fabrics in which the number of knit and purl stitches are not the same, such as stockinette/stocking stitch, have a tendency to curl; by contrast, those in which knit and purl stitches are arranged symmetrically (such as ribbing, garter stitch or seed/moss stitch) tend to lie flat and drape well. Wales of purl stitches have a tendency to recede, whereas those of knit stitches tend to come forward. Thus, the purl wales in ribbing tend to be invisible, since the neighboring knit wales come forward. Conversely, rows of purl stitches tend to form an embossed ridge relative to a row of knit stitches. This is the basis of shadow knitting, in which the appearance of a knitted fabric changes when viewed from different directions.[4]

Right- and left-plaited stitches

Both types of plaited stitches give a subtle but interesting visual texture, and tend to draw the fabric inwards, making it stiffer. Plaited stitches are a common method for knitting jewelry from fine metal wire.

Edges and joins between fabrics

The initial and final edges of a knitted fabric are known as the cast-on and bound/cast-off edges. The side edges are known as the selvages; the word derives from "self-edges", meaning that the stitches do not need to be secured by anything else. Many types of selvages have been developed, with different elastic and ornamental properties.

Edges are introduced within a knitted fabric for button holes, pockets, or decoration, by binding/casting off and re-casting on again (horizontal) or by knitting the fabrics on either side of an edge separately.

Two knitted fabrics can be joined by embroidery-based grafting methods, most commonly the Kitchener stitch. New wales can be begun from any of the edges of a knitted fabric; this is known as picking up stitches and is the basis for entrelac, in which the wales run perpendicular to one another in a checkerboard pattern.

Cables, increases, and lace

When knit wales cross, a cable is formed. Cables patterns tend to draw the fabric together, making it denser and less elastic;[5] Aran sweaters are a common form of knitted cabling.[6] Arbitrarily complex braid patterns can be done in cable knitting.

Lace knitting consists of making patterns and pictures using holes in the knit fabric, rather than with the stitches themselves.[7] The large and many holes in lacy knitting makes it extremely elastic; for example, some Shetland "wedding-ring" shawls are so fine that they may be drawn through a wedding ring.

By combining increases and decreases, it is possible to make the direction of a wale slant away from vertical, even in weft knitting. This is the basis for bias knitting, and can be used for visual effect, similar to the direction of a brush-stroke in oil painting.

Ornamentations and additions

Various point-like ornaments may be added to a knit fabric for their look or to improve the wear of the fabric. Examples include various types of bobbles, sequins and beads. Long loops can also be drawn out and secured, forming a "shaggy" texture to the fabric; this is known as loop knitting. Additional patterns can be made on the surface of the knitted fabric using embroidery; if the embroidery resembles knitting, it is often called Swiss darning. Various closures for the garments, such as frogs and buttons can be added; usually buttonholes are knitted into the garment, rather than cut.

Ornamental pieces may also be knitted separately and then attached using applique. For example, differently colored leaves and petals of a flower could be knit separately and attached to form the final picture. Separately knitted tubes can be applied to a knitted fabric to form complex Celtic knots and other patterns that would be difficult to knit.

Unknitted yarns may be worked into knitted fabrics for warmth, as is done in tufting and "weaving" (also known as "couching").

Properties of fabrics

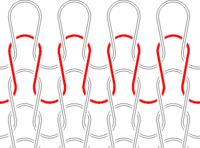

The topology of a knitted fabric is relatively complex. Unlike woven fabrics, where strands usually run straight horizontally and vertically, yarn that has been knitted follows a looped path along its row, as with the red strand in the diagram at left, in which the loops of one row have all been pulled through the loops of the row below it.

Because there is no single straight line of yarn anywhere in the pattern, a knitted piece of fabric can stretch in all directions. This elasticity is all but unavailable in woven fabrics which only stretch along the bias. Many modern stretchy garments, even as they rely on elastic synthetic materials for some stretch, also achieve at least some of their stretch through knitted patterns.

The basic knitted fabric (as in the diagram, and usually called a stocking or stockinette pattern) has a definite "right side" and "wrong side". On the right side, the visible portions of the loops are the verticals connecting two rows which are arranged in a grid of V shapes. On the wrong side, the ends of the loops are visible, both the tops and bottoms, creating a much more bumpy texture sometimes called reverse stockinette. (Despite being the "wrong side," reverse stockinette is frequently used as a pattern in its own right.) Because the yarn holding rows together is all on the front, and the yarn holding side-by-side stitches together is all on the back, stockinette fabric has a strong tendency to curl toward the front on the top and bottom, and toward the back on the left and right side.

Stitches can be worked from either side, and various patterns are created by mixing regular knit stitches with the "wrong side" stitches, known as purl stitches, either in columns (ribbing), rows (garter, welting), or more complex patterns. Each fabric has different properties: a garter stitch has much more vertical stretch, while ribbing stretches much more horizontally. Because of their front-back symmetry, these two fabrics have little curl, making them popular as edging, even when their stretch properties are not desired.

Different combinations of knit and purl stitches, along with more advanced techniques, generate fabrics of considerably variable consistency, from gauzy to very dense, from highly stretchy to relatively stiff, from flat to tightly curled, and so on.

Texture

The most common texture for a knitted garment is that generated by the flat stockinette stitch—as seen, though very small, in machine-made stockings and T-shirts—which is worked in the round as nothing but knit stitches, and worked flat as alternating rows of knit and purl. Other simple textures can be made with nothing but knit and purl stitches, including garter stitch, ribbing, and moss and seed stitches. Adding a "slip stitch" (where a loop is passed from one needle to the other) allows for a wide range of textures, including heel and linen stitches as well as a number of more complicated patterns.

Some more advanced knitting techniques create a surprising variety of complex textures. Combining certain increases, which can create small eyelet holes in the resulting fabric, with assorted decreases is key to creating knitted lace, a very open fabric resembling lace. Open vertical stripes can be created using the drop-stitch knitting technique. Changing the order of stitches from one row to the next, usually with the help of a cable needle or stitch holder, is key to cable knitting, producing an endless variety of cables, honeycombs, ropes, and Aran sweater patterning. Entrelac forms a rich checkerboard texture by knitting small squares, picking up their side edges, and knitting more squares to continue the piece.

Fair Isle knitting uses two or more colored yarns to create patterns and forms a thicker and less flexible fabric.

The appearance of a garment is also affected by the weight of the yarn, which describes the thickness of the spun fibre. The thicker the yarn, the more visible and apparent stitches will be; the thinner the yarn, the finer the texture.

Color

Plenty of finished knitting projects never use more than a single color of yarn, but there are many ways to work in multiple colors. Some yarns are dyed to be either variegated (changing color every few stitches in a random fashion) or self-striping (changing every few rows). More complicated techniques permit large fields of color (intarsia, for example), busy small-scale patterns of color (such as Fair Isle), or both (double knitting and slip-stitch color, for example).

Composition of knitted fabrics

The most common fibres used for knitted fabrics are cotton & viscose with or without elastane, these tend to be single jersey construction and are used for most t-shirt style tops.

History of fashion knitwear

Coco Chanel's 1916 use of jersey in her hugely influential suits was a turning point for knitwear, which became associated with the woman.[8] Shortly afterwards, Jean Patou's cubist-inspired, color-blocked knits were the sportswear of choice.[8]

In the 1940s came the iconic wearing of body-skimming sweaters by sex symbols like Lana Turner and Jane Russell, though the 1950s were dominated by conservative popcorn knits.[8] The swinging 1960s were famously manifested in Missoni's colorful zigzag knitwear.[8] This era also saw the rise both of Sonia Rykiel, dubbed the "Queen of Knitwear" for her vibrant striped sweaters and her clingy dresses, and of Kennedy-inspired preppy sweaters.[8]

In the 1980s, knitwear emerged from the realm of sportswear to dominate high fashion; notable designs included Romeo Gigli's "haute-bohemian cocoon coats" and Ralph Lauren's floor-length cashmere turtlenecks.[8]

Contemporary knitwear designers include Diane von Fürstenberg.[9]

See also

References

- ^ "Knitting Basics". Alamac American Knits LLC. 2004. Archived from the original on 2007-02-27. Retrieved 2006-12-27.

- ^ "Techniques with Theresa, Frog pond edition".

- ^ A wale, according to Knitting Technology: a Comprehensive Handbook and Practical Guide, is "a predominantly vertical column of needle loops generally produced by the same needles at successive (not necessarily all) knitting cycles. A wale starts as soon as an empty needle starts to knit" (Spencer 1989:17).

- ^ Høxbro, Vivian (2004). Shadow Knitting. Loveland, CO: Interweave Press. ISBN 978-1-931499-41-5.

- ^ Leapman, Melissa (2006). Cables Untangled: An Exploration of Cable Knitting. Potter Craft. ISBN 978-1-4000-9745-6.

- ^ Hollingworth, Shelagh (1983). The Complete Book of Traditional Aran Knitting. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-15635-0.

- ^ Sowerby, Jane (2006). Victorian Lace Today. XRX Books. ISBN 978-1-933064-07-9.

Swansen, Meg (2005). A Gathering of Lace (2nd ed.). Schoolhouse Press. ISBN 978-1-893762-24-4. - ^ a b c d e f Vargas, Whitney. "Knitting Circle." Elle (Sept 2007): p192.

- ^ Bansal, Paritosh (2008-01-24). "Designer Von Furstenberg sues Target over dress". Reuters.