Pranayama

Pranayama is the yogic practice of focusing on breath. In Sanskrit, prana means "vital life force", and yama means to gain control. In yoga, breath is associated with the prana, thus, pranayama is a means to elevate the prana shakti, or life energies. Pranayama is described in Hindu texts like the Bhagavad Gita and the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. Later in Hatha yoga texts, it meant the complete suspension of breathing.

Etymology

Prāṇāyāma (Devanagari: प्राणायाम prāṇāyāma) is a Sanskrit compound. It is defined variously by different authors.

Macdonell gives the etymology as prana (prāṇa), breath, + āyāma and defines it as the suspension of breath.[1]

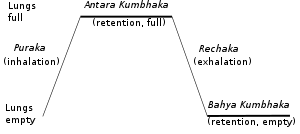

Monier-Williams defines the compound prāṇāyāma as "of the three 'breath-exercises' performed during Saṃdhyā (See pūrak, rechak (English: retch or throw out), kumbhak".[2] This technical definition refers to a particular system of breath control with three processes as explained by Bhattacharyya: pūrak (to take the breath inside), kumbhak (to retain it), and rechak (to discharge it). There are other processes of prāṇāyāma besides this three-step model.[3]

V. S. Apte's definition of āyāmaḥ derives it from ā + yām and provides several variant meanings for it when used in compounds. The first three meanings have to do with "length", "expansion, extension", and "stretching, extending", but in the specific case of use in the compound prāṇāyāma he defines āyāmaḥ as meaning "restrain, control, stopping".[4]

Ramamurti Mishra gives the definition:

Expansion of individual energy into cosmic energy is called prāṇāyāma (prāṇa, energy + ayām, expansion).[5]

Hinduism

Bhagavad Gītā

Pranayama is mentioned in verse 4.29 of the Bhagavad Gītā, which states "Still others, who are inclined to the process of breath restraint to remain in trance, practice by offering the movement of the outgoing breath into the incoming, and the incoming breath into the outgoing, and thus at last remain in trance, stopping all breathing. Others, curtailing the eating process, offer the outgoing breath into itself as a sacrifice."[6][7]

Yoga Sutras of Patanjali

Pranayama is the fourth "limb" of the eight limbs of Ashtanga Yoga mentioned in verse 2.29 in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali.[8][9] Patanjali, a Hindu Rishi, discusses his specific approach to pranayama in verses 2.49 through 2.51, and devotes verses 2.52 and 2.53 to explaining the benefits of the practice.[10] Patanjali does not fully elucidate the nature of prana, and the theory and practice of pranayama seem to have undergone significant development after him.[11] He presents pranayama as essentially an exercise that is preliminary to concentration.

Yoga teachers including B. K. S. Iyengar have advised that pranayama should be part of an overall practice that includes the other limbs of Patanjali's Raja Yoga teachings, especially Yama, Niyama, and Asana.[12]

Hatha yoga

The Indian tradition of Hatha Yoga makes use of various pranayama techniques. The 15th century Hatha Yoga Pradipika is a key text of this tradition and includes various forms of pranayama such as Kumbhaka breath retention and various body locks (Bandhas).[13] Other forms of pranayama breathing include Ujjayi breath ("Victorious Breath"), Sitali (breathing through the rolled tongue),[14] Bhastrika ("Bellows Breath"), Kapalabhati ("Skull-shining Breath", a Shatkarma purification),[15] Surya Bhedana ("Sun-piercing Breath"),[16] and the soothing Bhramari (buzzing like a bee).[17] B. K. S. Iyengar cautions that pranayama should only be undertaken when one has a firmly established yoga practice and then only under the guidance of an experienced Guru.[12]

According to the scholar-practitioner of yoga Theos Bernard, the ultimate aim of pranayama is the suspension of breathing (kevala kumbhaka), "causing the mind to swoon".[18] Paramahansa Yogananda writes, "The real meaning of Pranayama, according to Patanjali, the founder of Yoga philosophy, is the gradual cessation of breathing, the discontinuance of inhalation and exhalation".[19]

Yoga as exercise

The yoga scholar Andrea Jain states that pranayama was "marginal to the most widely cited sources" before the 20th century, and that the breathing practices were "dramatically" unlike the modern ones; she writes that while pranayama in modern yoga as exercise consists of synchronising the breath with movements (between asanas), in texts like the Bhagavad Gita and the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, pranayama meant "complete cessation of breathing", for which she cites Bronkhorst 2007.[20][21]

Buddhism

According to the Pali Buddhist Canon, the Buddha prior to his enlightenment practiced a meditative technique which involved pressing the palate with the tongue and forcibly attempting to restrain the breath. This is described as both extremely painful and not conducive to enlightenment.[22] In some Buddhist teachings or metaphors, breathing is said to stop with the fourth jhana, though this is a side-effect of the technique and does not come about as the result of purposeful effort.[23]

The Buddha did incorporate moderate modulation of the length of breath as part of the preliminary tetrad in the Anapanasati Sutta. Its use there is preparation for concentration. According to commentarial literature, this is appropriate for beginners.[24]

Indo-Tibetan tradition

Later Indo-Tibetan developments in Buddhist pranayama which are similar to Hindu forms can be seen as early as the 11th century, in the Buddhist text titled the Amṛtasiddhi, which teaches three bandhas in connection with yogic breathing (kumbakha).[25]

Tibetan Buddhist breathing exercises such as the "nine breathings of purification" or the "Ninefold Expulsion of Stale Vital Energy" (rlung ro dgu shrugs), a form of alternate nostril breathing, commonly include visualizations.[26][27] In the Nyingma tradition of Dzogchen these practices are collected in the textual cycle known as "The Oral Transmission of Vairotsana" (Vai ro snyan brgyud).[28]

Effects

A Cochrane systematic review on the symptomatic relief of mild to moderate asthma by breathing exercises stated that there was limited evidence they might bring about improvement in quality of life, hyperventilation symptoms, and lung function.[29][30]

Although relatively safe, Hatha Yoga is not risk free. Beginners should avoid advanced moves and exercise within their capabilities. Functional limitations should be taken into consideration.[31] According to at least one study, pranayama was the yoga practice leading to most injuries, with four injuries in a study of 76 practitioners. There have been limited reports of adverse effects including haematoma and pneumothorax, though the connections are not always well established.[31]

See also

References

- ^ Macdonell 1996, p. 185, main entry prāṇāghāta.

- ^ Monier-Williams, p. 706, left column.

- ^ Bhattacharyya 1999, p. 429.

- ^ See main article आयामः (āyāmaḥ) in: Apte, p. 224. Passages cited by Apte for this usage are Bhagavatgita 4.29 and Manusmriti 2.83.

- ^ Mishra, p. 216.

- ^ Gambhirananda, pp. 217–218.

- ^ "Bhagwat Geeta 4.29". Bhagwat Geeta with commentaries of Ramanuja, Madhva, Shankara and others. 13 Sep 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ^ Taimni 1961, p. 205.

- ^ Flood 1996, p. 97.

- ^ Taimni 1961, pp. 258–268.

- ^ G. C. Pande, Foundations of Indian Culture: Spiritual Vision and Symbolic Forms in Ancient India. Second edition published by Motilal Banarsidass Publ., 1990, p. 97.

- ^ a b Iyengar, B. K. S. (2011). Light on prāṇāyāma: the yogic art of breathing. New York: Crossroad. OCLC 809217248.

- ^ Mallinson, James (2011). Knut A. Jacobsen; et al., eds. Haṭha Yoga in the Brill Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 3. Brill Academic. pp. 772-773. ISBN 978-90-04-27128-9.

- ^ Mallinson, James (2012). "The Original Gorakṣaśataka". In White, David Gordon (ed.). Yoga in Practice. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 257–272.

- ^ Budilovsky, Joan; Adamson, Eve (2000). The complete idiot's guide to yoga (2 ed.). Penguin. Chapter 7. ISBN 978-0-02-863970-3.

- ^ "Surya Bhedana Pranayama". Yogapedia. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

In its simplest form, surya bhedana pranayama is inhaling fully through the right nostril, holding the breath and then exhaling through the left nostril. ... The pingala nadi, which represents masculine sun energy, begins in the muladhara (root) chakra and ends at the right nostril, which serves as a sort of entrance to this sun energy. By practicing surya bhedana pranayama, the yogi taps into and activates the pingala nadi energy

- ^ Brahinsky, Rachel (12 April 2017). "Use "Bee Breath" to Get Anxiety to Buzz Off". Yoga Journal. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ^ Bernard, Theos (2007). Hatha Yoga: The Report of A Personal Experience. Harmony. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-9552412-2-2. OCLC 230987898.

- ^ Yogananda, Paramahansa (2005). The Essence of Kriya Yoga (1st ed.). Alight Publications. p. part10 (online). ISBN 978-1931833189.

- ^ Bronkhorst, Johannes (2007). Greater Maghada: Studies in the Culture of Early India. Brill. pp. 26–27.

- ^ Jain, Andrea (2015). Selling Yoga: from Counterculture to Pop culture. Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-19-939024-3. OCLC 878953765.

- ^ Johannes Bronkhorst, The Two Traditions of Meditation in Ancient India. Franz Steiner Verlag Weisbaden GmbH, pp. 1–5.

- ^ Johannes Bronkhorst, The Two Traditions of Meditation in Ancient India. Franz Steiner Verlag Weisbaden GmbH, p. 84.

- ^ Edward Conze, Buddhist Meditation. Harper & Row, 1956, p. 66. Regarding the Buddha's incorporation of pranayama see also Buddhadasa, Mindfulness with Breathing. Revised edition published by Wisdom Publications, 1997, p. 53.

- ^ Mallinson, James (2018). Dominic Goodall; Shaman Hatley; Harunaga Isaacson (eds.). The Amṛtasiddhi: Haṭhayoga's Tantric Buddhist Source Text. Leiden: Brill. pp. 1–3 with footnotes.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Tenzin Wangyal. Awakening the Sacred Body, page 1

- ^ B. Alan Wallace. Tsalung Practice-Ninefold Expulsion of Stale Vital Energy (video). Meridian Trust. Retrieved 2017-08-16.

- ^ Chogyal Namkhai Norbu, Trans. by Adriano Clemente. Yantra Yoga Snow Lion Publications, p. 1.

- ^ Holland, Anne E.; Hill, Catherine J.; Jones, Alice Y.; McDonald, Christine F. (2012). "Breathing exercises for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10: CD008250. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008250.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 23076942.

- ^ Thayla, S. A.; Gabriela, S. S.; Diana, A. F.; Guilherme, A. F.; Karla, M. P. (25 March 2020). "Breathing exercises for adults with asthma". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (3): CD001277. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001277.pub4. PMC 7096190. PMID 32212422.

- ^ a b Cramer, H.; Krucoff, C.; Dobos, G. (2013). "Adverse events associated with yoga: a systematic review of published case reports and case series". PLOS ONE (Systematic review). 8 (10): e75515. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...875515C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0075515. PMC 3797727. PMID 24146758.

Sources

- Bhattacharyya, Narendra Nath (1999). History of the Tantric Religion (Second ed.). Delhi: Manohar Publications. ISBN 81-7304-025-7.

- Flood, Gavin D. (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press.

- Macdonell, Arthur Anthony (1996). A Practical Sanskrit Dictionary. Munshiram Monoharlal Publishers. ISBN 81-215-0715-4.

- Mishra, Ramamurti. Fundamentals of Yoga. Baba Bhagavandas Publication Trust.

- Taimni, I. K. (1961). The Science of Yoga (Eighth Reprint, 1993 ed.). Adyar, India: The Theosophical Publishing House. ISBN 81-7059-212-7.

- Zaccaro, Andrea et al. (2018). How Breath-Control Can Change Your Life: A Systematic Review on Psycho-Physiological Correlates of Slow Breathing. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience.

- Benefits and Power of Pranayama – Kaivalyadhama