Zodiac

The zodiac is a belt-shaped region of the sky that extends approximately 8° north or south (as measured in celestial latitude) of the ecliptic, the apparent path of the Sun across the celestial sphere over the course of the year. The paths of the Moon and visible planets are within the belt of the zodiac.[1]

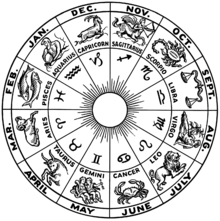

In Western astrology, and formerly astronomy, the zodiac is divided into twelve signs, each occupying 30° of celestial longitude and roughly corresponding to the following star constellations: Aries, Taurus, Gemini, Cancer, Leo, Virgo, Libra, Scorpio, Sagittarius, Capricorn, Aquarius, and Pisces.[2][3]

These astrological signs form a celestial coordinate system, or more specifically an ecliptic coordinate system, which takes the ecliptic as the origin of latitude and the Sun's position at vernal equinox as the origin of longitude.[4]

Name

The English word zodiac derives from zōdiacus,[5] the Latinized form of the Ancient Greek zōdiakòs kýklos (ζῳδιακός κύκλος),[citation needed] meaning "cycle or circle of little animals". Zōdion (ζῴδιον) is the diminutive of zōon (ζῷον, "animal"). The name reflects the prominence of animals (and mythological hybrids) among the twelve signs.

Usage

The zodiac was in use by the Roman era, based on concepts inherited by Hellenistic astronomy from Babylonian astronomy of the Chaldean period (mid-1st millennium BC), which, in turn, derived from an earlier system of lists of stars along the ecliptic.[6] The construction of the zodiac is described in Ptolemy's comprehensive 2nd century AD work, the Almagest.[7]

Although the zodiac remains the basis of the ecliptic coordinate system in use in astronomy besides the equatorial one,[8][9] the term and the names of the twelve signs are today mostly associated with horoscopic astrology.[10] The term "zodiac" may also refer to the region of the celestial sphere encompassing the paths of the planets corresponding to the band of about 8 arc degrees above and below the ecliptic. The zodiac of a given planet is the band that contains the path of that particular body; e.g., the "zodiac of the Moon" is the band of 5° above and below the ecliptic. By extension, the "zodiac of the comets" may refer to the band encompassing most short-period comets.[11]

History

Early history

As early as the 14th century BC a complete list of the 36 Egyptian decans was placed among the hieroglyphs adorning the tomb of Seti I; they figured again in the temple of Ramesses II, and characterize every Egyptian astrological monument. Both the famous zodiacs of Dendera display their symbols, identified by Karl Richard Lepsius.[12]

The division of the ecliptic into the zodiacal signs originates in Babylonian astronomy during the first half of the 1st millennium BC. The zodiac draws on stars in earlier Babylonian star catalogues, such as the MUL.APIN catalogue, which was compiled around 1000 BC. Some constellations can be traced even further back, to Bronze Age (First Babylonian dynasty) sources, including Gemini "The Twins," from MAŠ.TAB.BA.GAL.GAL "The Great Twins," and Cancer "The Crab," from AL.LUL "The Crayfish," among others.[citation needed]

Around the end of the 5th century BC, Babylonian astronomers divided the ecliptic into 12 equal "signs", by analogy to 12 schematic months of 30 days each. Each sign contained 30° of celestial longitude, thus creating the first known celestial coordinate system. According to calculations by modern astrophysics, the zodiac was introduced between 409 and 398 BC, during Persian rule,[13] and probably within a very few years of 401 BC.[14] Unlike modern astrologers, who place the beginning of the sign of Aries at the position of the Sun at the vernal equinox in the Northern Hemisphere (March equinox), Babylonian astronomers fixed the zodiac in relation to stars, placing the beginning of Cancer at the "Rear Twin Star" (β Geminorum) and the beginning of Aquarius at the "Rear Star of the Goat-Fish" (δ Capricorni).[15]

Due to the precession of the equinoxes, the time of year the Sun is in a given constellation has changed since Babylonian times, the point of March equinox has moved from Aries into Pisces.[16]

Because the division was made into equal arcs, 30° each, they constituted an ideal system of reference for making predictions about a planet's longitude. However, Babylonian techniques of observational measurements were in a rudimentary stage of evolution.[17] They measured the position of a planet in reference to a set of "normal stars" close to the ecliptic (±9° of latitude) as observational reference points to help positioning a planet within this ecliptic coordinate system.[18]

In Babylonian astronomical diaries, a planet position was generally given with respect to a zodiacal sign alone, less often in specific degrees within a sign.[19] When the degrees of longitude were given, they were expressed with reference to the 30° of the zodiacal sign, i.e., not with a reference to the continuous 360° ecliptic.[19] In astronomical ephemerides, the positions of significant astronomical phenomena were computed in sexagesimal fractions of a degree (equivalent to minutes and seconds of arc).[20] For daily ephemerides, the daily positions of a planet were not as important as the astrologically significant dates when the planet crossed from one zodiacal sign to the next.[19]

Hebrew astronomy and astrology

Knowledge of the Babylonian zodiac is said to be reflected in the Hebrew Bible; E. W. Bullinger interpreted the creatures appearing in the book of Ezekiel as the middle signs of the four quarters of the zodiac,[21][22] with the Lion as Leo, the Bull is Taurus, the Man representing Aquarius and the Eagle representing Scorpio.[23] Some authors have linked the twelve tribes of Israel with the same signs or the lunar Hebrew calendar having twelve lunar months in a lunar year. Martin and others have argued that the arrangement of the tribes around the Tabernacle (reported in the Book of Numbers) corresponded to the order of the zodiac, with Judah, Reuben, Ephraim, and Dan representing the middle signs of Leo, Aquarius, Taurus, and Scorpio, respectively. Such connections were taken up by Thomas Mann, who in his novel Joseph and His Brothers attributes characteristics of a sign of the zodiac to each tribe in his rendition of the Blessing of Jacob.[citation needed]

Hellenistic and Roman era

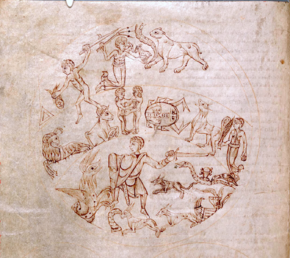

The Babylonian star catalogs entered Greek astronomy in the 4th century BC, via Eudoxus of Cnidus.[24][25] Babylonia or Chaldea in the Hellenistic world came to be so identified with astrology that "Chaldean wisdom" became among Greeks and Romans the synonym of divination through the planets and stars. Hellenistic astrology derived in part from Babylonian and Egyptian astrology.[26] Horoscopic astrology first appeared in Ptolemaic Egypt (305 BC–30 BC). The Dendera zodiac, a relief dating to ca. 50 BC, is the first known depiction of the classical zodiac of twelve signs.

The earliest extant Greek text using the Babylonian division of the zodiac into 12 signs of 30 equal degrees each is the Anaphoricus of Hypsicles of Alexandria (fl. 190 BC).[27] Particularly important in the development of Western horoscopic astrology was the astrologer and astronomer Ptolemy, whose work Tetrabiblos laid the basis of the Western astrological tradition.[28] Under the Greeks, and Ptolemy in particular, the planets, Houses, and signs of the zodiac were rationalized and their function set down in a way that has changed little to the present day.[29] Ptolemy lived in the 2nd century AD, three centuries after the discovery of the precession of the equinoxes by Hipparchus around 130 BC. Hipparchus's lost work on precession never circulated very widely until it was brought to prominence by Ptolemy,[30] and there are few explanations of precession outside the work of Ptolemy until late Antiquity, by which time Ptolemy's influence was widely established.[31] Ptolemy clearly explained the theoretical basis of the western zodiac as being a tropical coordinate system, by which the zodiac is aligned to the equinoxes and solstices, rather than the visible constellations that bear the same names as the zodiac signs.[32]

Hindu zodiac

According to mathematician-historian Montucla, the Hindu zodiac was adopted from the Greek zodiac through communications between ancient India and the Greek empire of Bactria.[33] The Hindu zodiac uses the sidereal coordinate system, which makes reference to the fixed stars. The tropical zodiac (of Mesopotamian origin) is divided by the intersections of the ecliptic and equator, which shifts in relation to the backdrop of fixed stars at a rate of 1° every 72 years, creating the phenomenon known as precession of the equinoxes. The Hindu zodiac, being sidereal, does not maintain this seasonal alignment, but there are still similarities between the two systems. The Hindu zodiac signs and corresponding Greek signs sound very different, being in Sanskrit and Greek respectively, but their symbols are nearly identical.[34] For example, dhanu means "bow" and corresponds to Sagittarius, the "archer", and kumbha means "water-pitcher" and corresponds to Aquarius, the "water-carrier".[35]

Middle Ages

During the Abbasid era, Greek reference books were systematically translated into Arabic, and Islamic astronomers then did their own observations, correcting Ptolemy's Almagest. One such book was Al-Sufi's Book Of Fixed Stars, which has pictorial depictions of 48 constellations. The book was divided into three sections: constellations of the zodiac, constellations north of the zodiac, and southern constellations. When Al-Sufi's book, and other works, were translated in the 11th century, there were mistakes made in the translations. As a result, some stars ended up with the names of the constellation they belong to (e.g. Hamal in Aries).

The High Middle Ages saw a revival of interest in Greco-Roman magic, first in Kabbalism and later continued in Renaissance magic. This included magical uses of the zodiac, as found, e.g., in the Sefer Raziel HaMalakh.

The zodiac is found in medieval stained glass as at Angers Cathedral, where the master glass maker, André Robin, made the ornate rosettes for the North and South transepts after the fire there in 1451.[36]

Mughal king Jahangir issued an attractive series of coins in gold and silver depicting the twelve signs of the zodiac.

Medieval Islamic era

Astrology emerged in the 8th century CE as a distinct discipline in Islam,[37]: 64 with a mix of Indian, Hellenistic Iranian and other traditions blended with Greek and Islamic astronomical knowledge, for example Ptolemy's work and Al-Sufi's Book of Fixed Stars. A knowledge of the influence that the stars have on events on the earth was important in Islamic civilization. As a rule, it was believed that the signs of the zodiac and the planets control the destiny not only of people but also of nations, and that the zodiac has the ability to determine a person's physical characteristics as well as intelligence and personal traits.[38]

The practice of astrology at this time could be divided into 4 broader categories: Genethlialogy, Catarchic Astrology, Interrogational Astrology and General Astrology.[37]: 65 However the most common type of astrology was Genethlialogy, which examined all aspects of a person's life in relation to the planetary positions at their birth; more commonly known as our horoscope.[37]: 65

Astrology services were offered widely across the empire, mainly in bazaars, where people could pay for a reading.[39] Astrology was valued in the royal courts, for example, the Abbasid Caliph Al-Mansur used astrology to determine the best date for founding the new capital of Baghdad.[37]: 66 However, whilst horoscopes were generally widely accepted by society, many scholars condemned the use of astrology and divination; linking it to occult influences.[40] Many theologians and scholars thought that it went against the tenets of Islam; as only God should be able to determine events rather than astrologers looking at the positions of the planets.[39]

In order to calculate someone's horoscope, an astrologer would use 3 tools: an astrolabe, ephemeris and a takht. First, the astrologer would use an astrolabe to find the position of the sun, align the rule with the persons time of birth and then align the rete to establish the altitude of the sun on that date.[41] Next, the astrologer would use an Ephemeris, a table denoting the mean position of the planets and stars within the sky at any given time.[42] Finally, the astrologer would add the altitude of the sun taken from the astrolabe, with the mean position of the planets on the person's birthday, and add them together on the takht (also known as the dustboard).[42] The dust board was merely a tablet covered in sand; on which the calculations could be made and erased easily.[39] Once this had been calculated, the astrologer was then able to interpret the horoscope. Most of these interpretations were based on the zodiac in literature. For example, there were several manuals on how to interpret each zodiac sign, the treatise relating to each individual sign and what the characteristics of these zodiacs were.[39]

Early modern

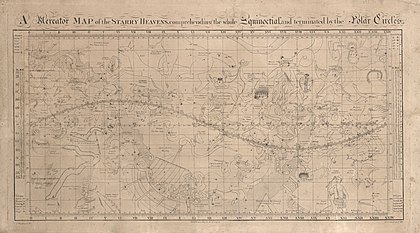

An example of the use of signs as astronomical coordinates may be found in the Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris for the year 1767. The "Longitude of the Sun" columns show the sign (represented as a digit from 0 to and including 11), degrees from 0 to 29, minutes, and seconds.[43]

The zodiac symbols are Early Modern simplifications of conventional pictorial representations of the signs, attested since Hellenistic times.[citation needed]

Twelve signs

What follows is a list of the signs of the modern zodiac (with the ecliptic longitudes of their first points), where 0° Aries is understood as the vernal equinox, with their Latin, Greek, Sanskrit, and Babylonian names. But note that the Sanskrit and the name equivalents (after c.500 BC) denote the constellations only, not the tropical zodiac signs. The "English translation" isn't usually used by English speakers. The Latin names are standard English usage (except that "Capricorn" is used rather than "Capricornus").

| House | Unicode Character | Ecliptic Longitude (a ≤ λ < b) |

Latin name | Gloss | Greek name (Romanization of Greek) | Sanskrit name | Sumero-Babylonian name[44] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ♈︎︎ | 0° | Aries | Ram | Κριός (Krios) | Meṣa (मेष) | MUL LU.ḪUN.GA[45] "Agrarian Worker", Dumuzi |

| 2 | ♉︎︎ | 30° | Taurus | Bull | Ταῦρος (Tauros) | Vṛṣabha (वृषभ) | MULGU4.AN.NA "Divine Bull of Heaven" |

| 3 | ♊︎︎ | 60° | Gemini | Twins | Δίδυμοι (Didymoi) | Mithuna (मिथुन) | MULMAŠ.TAB.BA.GAL.GAL "Great Twins" |

| 4 | ♋︎︎ | 90° | Cancer | Crab | Καρκίνος (Karkinos) | Karka (कर्क) | MULAL.LUL "Crayfish" |

| 5 | ♌︎︎ | 120° | Leo | Lion | Λέων (Leōn) | Siṃha (सिंह) | MULUR.GU.LA "Lion" |

| 6 | ♍︎︎ | 150° | Virgo | Maiden | Παρθένος (Parthenos) | Kanyā (कन्या) | MULAB.SIN "The Furrow"* *"The goddess Shala's ear of grain" |

| 7 | ♎︎︎ | 180° | Libra | Scales | Ζυγός (Zygos) | Tulā (तुला) | MULZIB.BA.AN.NA "Scales" |

| 8 | ♏︎︎ | 210° | Scorpio | Scorpion | Σκoρπίος (Skorpios)[46] | Vṛścika (वृश्चिक) | MULGIR.TAB "Scorpion" |

| 9 | ♐︎︎ | 240° | Sagittarius | (Centaur) Archer | Τοξότης (Toxotēs) | Dhanuṣa (धनुष) | MULPA.BIL.SAG, Nedu "soldier" |

| 10 | ♑︎︎ | 270° | Capricornus | Mountain Goat or "Goat-horned" Sea-Goat | Αἰγόκερως (Aigokerōs) | Makara (मकर) | MULSUḪUR.MAŠ "Goat-Fish" of Enki |

| 11 | ♒︎︎ | 300° | Aquarius | Water-Bearer | Ὑδροχόος (Hydrokhoos) | Kumbha (कुंभ) | MULGU.LA "Great One", later qâ "pitcher" |

| 12 | ♓︎︎ | 330° | Pisces | 2 Fish[47] | Ἰχθύες (Ikhthyes) | Mīna (मीन) | MULSIM.MAḪ "Tail of the Swallow"; DU.NU.NU "fish-cord" |

The following table compares the Gregorian dates on which the Sun enters a sign in the Ptolemaic tropical zodiac, and a sign in the sidereal system proposed by Cyril Fagan.

The beginning of Aries is defined as the moment of vernal equinox, and all other dates shift accordingly.[48] The precise Gregorian times and dates vary slightly from year to year as the Gregorian calendar shifts relative to the tropical year. These variations remain within less than two days' difference in the recent past and the near-future, vernal equinox in UT always falling either on 20 or 21 March in the period of 1797 to 2043, falling on 19 March in 1796 the last time and in 2044 the next. The vernal equinox has fallen on 20 March UT since 2008, and will continue to do so until 2043.[49]

| Name | Symbol[50] | Tropical zodiac[51][52] | Sidereal zodiac [undue weight? – discuss][53] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aries | 21 March – 20 April |

15 April – 15 May | |

| Taurus | 20 April – 21 May |

16 May – 15 June | |

| Gemini | 21 May – 21 June |

16 June – 15 July | |

| Cancer | 21 June – 23 July |

16 July – 15 August | |

| Leo | 23 July – 23 August |

16 August – 15 September | |

| Virgo | 23 August – 23 September |

16 September – 15 October | |

| Libra | 23 September – 23 October |

16 October – 16 November | |

| Scorpio | 23 October – 22 November |

17 November – 15 December | |

| Sagittarius | 23 November – 22 December |

16 December – 14 January | |

| Capricorn | 22 December – 20 January |

15 January – 14 February | |

| Aquarius | 20 January – 19 February |

15 February – 14 March | |

| Pisces | 19 February – 21 March |

15 March – 14 April |

As each sign takes up exactly 30 degrees of the zodiac, the average duration of the solar stay in each sign is one twelfth of a sidereal year, or 30.43 standard days. Due to Earth's slight orbital eccentricity, the duration of each sign varies appreciably, between about 29.4 days for Capricorn and about 31.4 days for Cancer (see Equation of time). In addition, because the Earth's axis is at an angle, some signs take longer to rise than others, and the farther away from the equator the observer is situated, the greater the difference. Thus, signs are spoken of as "long" or "short" ascension.[54]

Constellations

In tropical astrology, the zodiacal signs are distinct from the constellations associated with them, not only because of their drifting apart due to the precession of equinoxes but because the physical constellations take up varying widths of the ecliptic, so the Sun is not in each constellation for the same amount of time.[55]: 25 Thus, Virgo takes up 5 times as much ecliptic longitude as Scorpius. The zodiacal signs are an abstraction from the physical constellations, and each represent exactly 1⁄12th of the full circle, but the time spent by the Sun in each sign varies slightly due to the eccentricity of the Earth's orbit.

Sidereal astrology remedies this by assigning the zodiac sign approximately to the corresponding constellation. This alignment needs re calibrating every so often to keep the alignment in place.

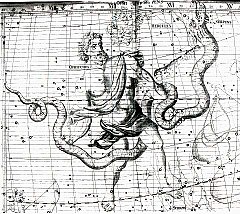

The ecliptic intersects with 13 constellations of Ptolemy's Almagest,[56] as well as of the more precisely delineated IAU designated constellations. In addition to the twelve constellations after which the twelve zodiac signs are named, the ecliptic intersects Ophiuchus,[57] the bottom part of which interjects between Scorpio and Sagittarius. Occasionally this difference between the astronomical constellations and the astrological signs is mistakenly reported in the popular press as a "change" to the list of traditional signs by some astronomical body like the IAU, NASA, or the Royal Astronomical Society. This happened in a 1995 report of the BBC Nine O'Clock News and various reports in 2011 and 2016.[58][59][60]

Some "parazodiacal" constellations are touched by the paths of the planets, leading to counts of up to 25 "constellations of the zodiac".[61] The ancient Babylonian MUL.APIN catalog lists Orion, Perseus, Auriga, and Andromeda. Modern astronomers have noted that planets pass through Crater, Sextans, Cetus, Pegasus, Corvus, Hydra, and Scutum, with Venus very rarely passing through Aquila, Canis Minor, Auriga, and Serpens.[61]

Some other constellations are mythologically associated with the zodiacal ones: Piscis Austrinus, The Southern Fish, is attached to Aquarius. In classical maps, it swallows the stream poured out of Aquarius' pitcher, but perhaps it formerly just swam in it. Aquila, The Eagle, was possibly associated with the zodiac by virtue of its main star, Altair.[citation needed] Hydra in the Early Bronze Age marked the celestial equator and was associated with Leo, which is shown standing on the serpent on the Dendera zodiac.[citation needed] Corvus is the Crow or Raven mysteriously perched on the tail of Hydra.

| Name | IAU boundaries[62] | Solar stay[62] | Brightest star |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aries | 19 April – 13 May | 25 days | Hamal |

| Taurus | 14 May – 19 June | 37 days | Aldebaran |

| Gemini | 20 June – 20 July | 31 days | Pollux |

| Cancer | 21 July – 9 August | 20 days | Al Tarf |

| Leo | 10 August – 15 September | 37 days | Regulus |

| Virgo | 16 September – 30 October | 45 days | Spica |

| Libra | 31 October – 22 November | 23 days | Zubeneschamali |

| Scorpius | 23 November – 29 November | 7 days | Antares |

| Ophiuchus | 30 November – 17 December | 18 days | Rasalhague |

| Sagittarius | 18 December – 18 January | 32 days | Kaus Australis |

| Capricornus | 19 January – 15 February | 28 days | Deneb Algedi |

| Aquarius | 16 February – 11 March | 24 days | Sadalsuud |

| Pisces | 12 March – 18 April | 38 days | Alpherg |

Precession of the equinoxes

The zodiac system was developed in Babylonia, some 2,500 years ago, during the "Age of Aries".[17] At the time, it is assumed, the precession of the equinoxes was unknown. Contemporary use of the coordinate system is presented with the choice of interpreting the system either as sidereal, with the signs fixed to the stellar background, or as tropical, with the signs fixed to the point (vector of the Sun) at the March equinox.[19]

Western astrology takes the tropical approach, whereas Hindu astrology takes the sidereal one. This results in the originally unified zodiacal coordinate system drifting apart gradually, with a clockwise (westward) precession of 1.4 degrees per century.

For the tropical zodiac used in Western astronomy and astrology, this means that the tropical sign of Aries currently lies somewhere within the constellation Pisces ("Age of Pisces").

The sidereal coordinate system takes into account the ayanamsa, ayan meaning "transit' or 'movement', and amsa meaning 'small part', i.e. movement of equinoxes in small parts. It is unclear when Indians became aware of the precession of the equinoxes, but Bhāskara II's 12th-century treatise Siddhanta Shiromani gives equations for measurement of precession of equinoxes, and says his equations are based on some lost equations of Suryasiddhanta plus the equation of Munjaala.

The discovery of precession is attributed to Hipparchus around 130 BC. Ptolemy quotes from Hipparchus' now lost work entitled "On the Displacement of the Solstitial and Equinoctial Points" in the seventh book of his 2nd century astronomical text, Almagest, where he describes the phenomenon of precession and estimates its value.[30] Ptolemy clarified that the convention of Greek mathematical astronomy was to commence the zodiac from the point of the vernal equinox and to always refer to this point as "the first degree" of Aries.[63] This is known as the "tropical zodiac" (from the Greek word trópos, turn)[64] because its starting point revolves through the circle of background constellations over time.

The principle of the vernal point acting as the first degree of the zodiac for Greek astronomers is described in the 1st century BC astronomical text of Geminus of Rhodes. Geminus explains that Greek astronomers of his era associate the first degrees of the zodiac signs with the two solstices and the two equinoxes, in contrast to the older Chaldean (Babylonian) system, which placed these points within the zodiac signs.[63] This illustrates that Ptolemy merely clarified the convention of Greek astronomers and did not originate the principle of the tropical zodiac, as is sometimes assumed.

Ptolemy demonstrates that the principle of the tropical zodiac was well known to his predecessors within his astrological text, the Tetrabiblos, where he explains why it would be an error to associate the regularly spaced signs of the seasonally aligned zodiac with the irregular boundaries of the visible constellations:

The beginnings of the signs, and likewise those of the terms, are to be taken from the equinoctial and tropical points. This rule is not only clearly stated by writers on the subject, but is especially evident by the demonstration constantly afforded, that their natures, influences and familiarities have no other origin than from the tropics and equinoxes, as has been already plainly shown. And, if other beginnings were allowed, it would either be necessary to exclude the natures of the signs from the theory of prognostication, or impossible to avoid error in then retaining and making use of them; as the regularity of their spaces and distances, upon which their influence depends, would then be invaded and broken in upon.[32]

In modern astronomy

Astronomically, the zodiac defines a belt of space extending 8°[65] or 9° in celestial latitude to the north and south of the ecliptic, within which the orbits of the Moon and the principal planets remain.[66] It is a feature of the ecliptic coordinate system – a celestial coordinate system centered upon the ecliptic (the plane of the Earth's orbit and the Sun's apparent path), by which celestial longitude is measured in degrees east of the vernal equinox (the ascending intersection of the ecliptic and equator).[67] The zodiac is narrow in angular terms because most of the Sun's planets have orbits that have only a slight inclination to the orbital plane of the Earth.[68] Stars within the zodiac are subject to occultations by the Moon and other solar system bodies. These events can be useful, for example, to estimate the cross-sectional dimensions of a minor planet, or check a star for a close companion.[69]

The Sun's placement upon the vernal equinox, which occurs annually around 21 March, defines the starting point for measurement, the first degree of which is historically known as the "first point of Aries". The first 30° along the ecliptic is nominally designated as the zodiac sign Aries, which no longer falls within the proximity of the constellation Aries since the effect of precession is to move the vernal point through the backdrop of visible constellations (it is currently located near the end of the constellation Pisces, having been within that constellation since the 2nd century AD).[70] The subsequent 30° of the ecliptic is nominally designated the zodiac sign Taurus, and so on through the twelve signs of the zodiac so that each occupies 1⁄12th (30°) of the zodiac's great circle. Zodiac signs have never been used to determine the boundaries of astronomical constellations that lie in the vicinity of the zodiac, which are, and always have been, irregular in their size and shape.[66]

The convention of measuring celestial longitude within individual signs was still being used in the mid-19th century,[71] but modern astronomy now numbers degrees of celestial longitude continuously from 0° to 360°, rather than 0° to 30° within each sign.[72] This coordinate system is primary used by astronomers for observations of solar system objects.[73]

The use of the zodiac as a means to determine astronomical measurement remained the main method for defining celestial positions by Western astronomers until the Renaissance, at which time preference moved to the equatorial coordinate system, which measures astronomical positions by right ascension and declination rather than the ecliptic-based definitions of celestial longitude and celestial latitude. The orientation of equatorial coordinates are aligned with the Earth's axis of rotation, rather than the plane of the planet's orbit around the Sun.[70]

The word "zodiac" is used in reference to the zodiacal cloud of dust grains that move among the planets, and the zodiacal light that originates from their scattering of sunlight.[74] While its name is derived from the zodiac, the zodiacal light covers the entire night sky, with enhancements in certain directions.[75]

Unicode characters

In Unicode, the symbols of zodiac signs are encoded in block "Miscellaneous Symbols". They can be forced to look like text by appending U+FE0E, or like emojis by appending U+FE0F:[50]

| Unicode character | text | emoji |

|---|---|---|

| U+2648 ♈ ARIES | ♈︎ | ♈️ |

| U+2649 ♉ TAURUS | ♉︎ | ♉️ |

| U+264A ♊ GEMINI | ♊︎ | ♊️ |

| U+264B ♋ CANCER | ♋︎ | ♋️ |

| U+264C ♌ LEO | ♌︎ | ♌️ |

| U+264D ♍ VIRGO | ♍︎ | ♍️ |

| U+264E ♎ LIBRA | ♎︎ | ♎️ |

| U+264F ♏ SCORPIUS | ♏︎ | ♏️ |

| U+2650 ♐ SAGITTARIUS | ♐︎ | ♐️ |

| U+2651 ♑ CAPRICORN | ♑︎ | ♑️ |

| U+2652 ♒ AQUARIUS | ♒︎ | ♒️ |

| U+2653 ♓ PISCES | ♓︎ | ♓️ |

| U+26CE ⛎ OPHIUCHUS | ⛎︎ | ⛎️ |

See also

References

- ^ "zodiac". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 26 September 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ Because the signs are each 30° in longitude but constellations have irregular shapes, and because of precession, they do not correspond exactly to the boundaries of the constellations after which they are named.

- ^ Noble, William (1902), "Papers communicated to the Association. The Signs of the Zodiac.", Journal of the British Astronomical Association, 12: 242–244, Bibcode:1902JBAA...12..242N

- ^ Leadbetter, Charles (1742), A Compleat System of Astronomy, J. Wilcox, London, p. 94; numerous examples of this notation appear throughout the book.

- ^ Skeat, Walter William (1924). A Concise Etymological Dictionary of the English Language. Clarendon Press. p. 622.

- ^ See MUL.APIN. See also Lankford, John; Rothenberg, Marc (1997). History of Astronomy: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-8153-0322-0.

- ^ Ptolemy, Claudius (1998). The Almagest. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00260-6. Translated and annotated by G. J. Toomer; with a foreword by Owen Gingerich.

- ^ Shapiro, Lee T. "Constellations in the zodiac". NASA. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- ^ Timberlake, Todd; Wallace, Paul (28 March 2019). Finding Our Place in the Solar System: The Scientific Story of the Copernican Revolution. Cambridge University Press. p. 33. ISBN 9781107182295.

- ^ van der Waerden, B. L. (1953). "History of the zodiac". Archiv für Orientforschung. 16: 216–230. Bibcode:1953ArOri..16..216V.

- ^ OED, citing J. Harris, Lexicon Technicum (1704): "Zodiack of the Comets, Cassini hath observed a certain Tract [...] within whose Bounds [...] he hath found most Comets [...] to keep."

- ^ One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Clerke, Agnes Mary (1911). "Zodiac". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 997.

- ^ Ossendrijver, Mathieu (2013). "Science, Mesopotamian" (PDF). doi:10.1002/9781444338386.wbeah21289. ISBN 9781405179355. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Britton, John P. (2010), "Studies in Babylonian lunar theory: part III. The introduction of the uniform zodiac", Archive for History of Exact Sciences, 64 (6): 617–663, doi:10.1007/S00407-010-0064-Z, JSTOR 41134332, S2CID 122004678,

[T]he zodiac was introduced between −408 and −397 and probably within a very few years of −400.

- ^ Steele, John M. (2012) [2008], A Brief Introduction to Astronomy in the Middle East (electronic ed.), London: Saqi, ISBN 9780863568961

- ^ Plait, Phil (26 September 2016), "No, NASA hasn't changed the zodiac signs or added a new one", Bad Astronomy

- ^ a b Sachs, A. (1948). "A Classification of the Babylonian Astronomical Tablets of the Seleucid Period". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 2 (4). University of Chicago Press: 271–290. doi:10.2307/3515929. JSTOR 3515929. S2CID 164038422.

- ^ Aaboe, Asger H. (2001), Episodes from the Early History of Astronomy, New York: Springer, pp. 37–38, ISBN 9780387951362

- ^ a b c d Rochberg, Francesca (1988), Babylonian Horoscopes, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 88, American Philosophical Society, pp. i–164, doi:10.2307/1006632, JSTOR 1006632

- ^ Aaboe, Asger H. (2001), Episodes from the Early History of Astronomy, New York: Springer, pp. 41–45, ISBN 9780387951362

- ^ Bullinger, E.W. The Witness of the Stars

- ^ Kennedy, D. James. The Real Meaning of the Zodiac.

- ^ Richard Hinckley Allen, Star Names: Their Lore and Meaning, Vol. 1 (New York: Dover Publications, 1899, p. 213-215.) argued for Scorpio having previously been called Eagle. for Scorpio.

- ^ Rogers, John H. "Origins of the ancient constellations: I. The Mesopotamian traditions." Journal of the British Astronomical Assoc. 108.1 (1998): 9–28. Astronomical Data Service.

- ^ Rogers, John H. "Origins of the ancient constellations: II. The Mesopotamian traditions." Journal of the British Astronomical Assoc. 108.2 (1998): 79–89. Astronomical Data Service.

- ^ Powell, Robert, Influence of Babylonian Astronomy on the Subsequent Defining of the Zodiac (2004), PhD thesis, summarized by anonymous editor, Archived 21 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Montelle, Clemency (2016), "The Anaphoricus of Hypsicles of Alexandria", in Steele, John M. (ed.), The Circulation of Astronomical Knowledge in the Ancient World, Time, Astronomy, and Calendars: Texts and Studies, vol. 6, Leiden: Brill, pp. 287–315, ISBN 978-90-0431561-7

- ^ Saliba, George (1994). A History of Arabic Astronomy: Planetary Theories During the Golden Age of Islam. New York: New York University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-8147-8023-7.

- ^ Parker, Julia; Parker, Derek (1990). The New Compleat Astrologer. New York, NY: Crescent Books. p. 16. ISBN 978-0517697009.

- ^ a b Graßhoff, Gerd (1990). The History of Ptolemy's Star Catalogue. Springer. p. 73. ISBN 9780387971810.

- ^ Evans, James; Berggren, J. Lennart (2006). Geminos's Introduction to the Phenomena. Princeton University Press. p. 113. ISBN 069112339X.

- ^ a b Ashmand, J. M. (2011). Ptolemy's Tetrabiblos. Astrology Classics. p. 37 (I.XXV). ISBN 978-1461118251.

- ^ James Mill (1817). The History of British India. Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy. p. 409.

- ^ Schmidt, Robert H. "The Relation of Hellenistic to Indian Astrology". Project Hindsight. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ^ Dalal, Roshen (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books India. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- ^ King, David. 'Angers Cathedral', (book review of Karine Boulanger's 2010 book, Les Vitraux de la Cathédrale d'Angers, the 11th volume of the Corpus Vitrearum series from France), Vitemus: the only on-line magazine devoted to medieval stained glass, Issue 48, February 2011, retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ a b c d Ayduz, Salim (2014). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Science, and Technology in Islam. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Andalusi, Salem (1991). Science in the medical world: 'Book of the categories of nations. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. XXV.

- ^ a b c d Sardar, Marika. "Astronomy and Astrology in the Medieval Islamic World". Met Museum.

- ^ Varisco, Daniel Martin (2000). Selin, Helaine (ed.). Astronomy Across Cultures: The History of Non-Western Astrology. Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht. p. 617. ISBN 978-94-010-5820-9.

- ^ WInterburn, Emily (August 2005). "Using an Astrolabe". Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation: 7.

- ^ a b Saliba, George (1992). "The Role of the Astrologer in Medieval Islamic Society". Bulletin d'études orientales. 44: 50. JSTOR 41608345.

- ^ Nautical Almanac and Astronomical Ephemeris for the year 1767. London: Board of Longitude, 1766.

- ^ MUL.APIN; Peter Whitfield, History of Astrology (2001); W. Muss-Arnolt, The Names of the Assyro-Babylonian Months and Their Regents, Journal of Biblical Literature (1892).

- ^ "ccpo/qpn/Agru[1]". oracc.iaas.upenn.edu.

- ^ Alternative form: Σκορπίων Skorpiōn. Later form (with synizesis): Σκορπιός.

- ^ American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language 3rd ed., s.v. "Pisces."

- ^ ""Why is the vernal equinox called the "First Point of Aries" when the Sun is actually in Pisces on this date?"". University of Southern Maine. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ See Jean Meeus, Astronomical Tables of the Sun, Moon, and Planets, 1983 published by Willmann-Bell, Inc., Richmond, Virginia. The date in other time zones may vary.

- ^ a b "Zodiacal symbols in Unicode block Miscellaneous Symbols" (PDF). The Unicode Standard. 2010.

- ^ Powell, Robert (2017). History of the Zodiac. Sophia Academic Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-1597311526.

- ^ Dates are for a typical year; actual dates may vary by a day or so from year to year.

- ^ Not in use in either astronomy or mainstream astrology, based on Cyril Fagan, Zodiacs Old and New (1950).

- ^ Parker, Julia (2010) The Astrologer's Handbook. Alva Press, NJ. p. 10. ISBN 0916360598

- ^ James, Edward W. (1982). Patrick Grim (ed.). Philosophy of science and the occult. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0873955722.

- ^ Peters, Christian Heinrich Friedrich and Edward Ball Knobel. Ptolemy's Catalogue of Stars: a revision of the Almagest. Archived 29 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1915. Ptolemy (1982) [2nd cent.]. "VII.5". In R. Catesby Taliaferro (ed.). Almagest. p. 239. Ptolemy refers to the constellation as Septentarius "the serpent holder".

- ^ Tatum, Jeremy B. (June 2010). "The Signs and Constellations of the Zodiac". Journal of the Royal Society of Canada. 104 (3): 103. Bibcode:2010JRASC.104..103T.

- ^ Kollerstrom, N. (October 1995). "Ophiuchus and the media". The Observatory. 115. KNUDSEN; OBS: 261–262. Bibcode:1995Obs...115..261K.

- ^ The notion received further international media attention in January 2011, when it was reported that astronomer Parke Kunkle, a board-member of the Minnesota Planetarium Society, had suggested that Ophiuchus was the zodiac's "13th sign". He later issued a statement to say he had not reported that the zodiac ought to include 13 signs instead of 12, but was only mentioning that there were 13 constellations; reported in Mad Astronomy: "Why did your zodiac sign change?" 13 January 2011.

- ^ Plait, Phil (26 September 2016). "No, NASA Didn't Change Your Astrological Sign".

- ^ a b Mosley, John (2011). "The Real, Real Constellations of the Zodiac". International Planetarium Society. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- ^ a b The Real Constellations of the Zodiac. Lee T. Shapiro, director of Morehead Planetarium University of North Carolina (Spring 1977)

- ^ a b Evans, James; Berggren, J. Lennart (2006). Geminos's Introduction to the Phenomena. Princeton University Press. p. 115. ISBN 069112339X.

- ^ "tropo-". Dictionary.com. Random House, Inc. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- ^ Holmes, Charles Nevers (November 1914). "The Zodiac". Popular Astronomy. 22: 547–550. Bibcode:1914PA.....22..547H.

- ^ a b Encyclopædia Britannica. "Zodiac". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica. "Ecliptic". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ^ "Zodiac". Cosmos. Swinburne University of Technology. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ "International Occultation Timing Association". 18 December 2017. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ a b Encyclopædia Britannica. "Astronomical map". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ^ G. Rubie (1830). The British Celestial Atlas: Being a Complete Guide to the Attainment of a Practical Knowledge of the Heavenly Bodies. Baldwin & Cradock. p. 79.

The Longitude of a Celestial Object is reckoned on the Ecliptic, in signs and degrees, eastward from the first point of Aries.

- ^ The Astronomical Almanac for the Year 2017, Washington D. C.: U.S. Government Publishing Office, October 2015, pp. C6–C21, ISBN 978-0-7077-41666

- ^ Clark, Alan T.; et al. (2008). Observing Projects Using Starry Night Enthusiast (eighth ed.). W. H. Freeman. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-4292-1866-5.

- ^ Licquia, Timothy C.; Newman, Jeffrey A.; Brinchmann, Jarle (August 2015). "Unveiling the Milky Way: A New Technique for Determining the Optical Color and Luminosity of Our Galaxy". The Astrophysical Journal. 809 (1): 19. arXiv:1508.04446. Bibcode:2015ApJ...809...96L. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/809/1/96. S2CID 118455273. 96.

- ^ Edberg, Stephen J.; Levy, David H. (6 October 1994). Observing Comets, Asteroids, Meteors, and the Zodiacal Light. Cambridge University Press. p. 151. ISBN 9780521420037.

External links

- "A Treatise on Zodiacal Signs and Constellations: Unique Jewels on the Benefits of Keeping Time" is a manuscript that dates back to 1831 with a focus on Arabic, Coptic and Syriac calendars.

- Zodiac Constellations at Constellation Guide