Teratoma

| Teratoma | |

|---|---|

| |

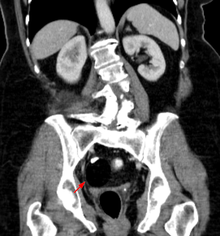

| A small (4 cm) dermoid cyst of an ovary, discovered during cesarean section | |

| Specialty | Gynecology, oncology |

| Symptoms | Minimal, painless lump[1][2] |

| Complications | Ovarian torsion, testicular torsion, hydrops fetalis[1][2][3] |

| Types | Mature, immature[4] |

| Causes | Unknown[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Tissue biopsy[2] |

| Differential diagnosis | Lipoma, dermoid, myelomeningocele[5] |

| Treatment | Surgery, chemotherapy[5][6] |

| Frequency | 1 in 30,000 newborns (coccyx)[7] |

A teratoma is a tumor made up of several types of tissue, such as hair, muscle, teeth, or bone.[4] Teratomata typically form in the tailbone (where it is known as a sacrococcygeal teratoma), ovary, or testicle.[4]

Symptoms

[edit]Symptoms may be minimal if the tumor is small.[2] A testicular teratoma may present as a painless lump.[1] Complications may include ovarian torsion, testicular torsion, or hydrops fetalis.[1][2][3]

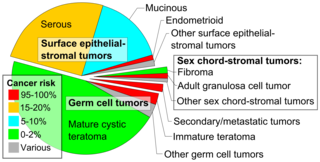

They are a type of germ cell tumor (a tumor that begins in the cells that give rise to sperm or eggs).[4][8] They are divided into two types: mature and immature.[4] Mature teratomas include dermoid cysts and are generally benign.[8] Immature teratomas may be cancerous.[4][9] Most ovarian teratomas are mature.[10] In adults, testicular teratomas are generally cancerous.[11] Definitive diagnosis is based on a tissue biopsy.[2]

Treatment of coccyx, testicular, and ovarian teratomas is generally by surgery.[5][6][12] Testicular and immature ovarian teratomas are also frequently treated with chemotherapy.[6][10]

Teratomas occur in the coccyx in about one in 30,000 newborns, making them one of the most common tumors in this age group.[5][7] Females are affected more often than males.[5] Ovarian teratomas represent about a quarter of ovarian tumors and are typically noticed during middle age.[10] Testicular teratomas represent almost half of testicular cancers.[13] They can occur in both children and adults.[14] The term comes from the Greek word for "monster"[15] plus the "-oma" suffix used for tumors.

Teratomas can cause an autoimmune illness called Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis. In this condition, the teratomas may contain B cells with NMDA-receptor specificities.[16]

After teratoma removal surgery, a risk exists of regrowth in place, or in nearby organs.[17]

Types

[edit]Mature teratoma

[edit]

A mature teratoma is a grade 0 teratoma. They are highly variable in form and histology, and may be solid, cystic, or a combination of the two. A mature teratoma often contains several different types of tissue such as skin, muscle, and bone. Skin may surround a cyst and grow abundant hair . Mature teratomas generally are benign, with 0.17–2% of mature cystic teratomas becoming malignant.[18]

Immature teratoma

[edit]Immature teratoma is the malignant counterpart of the mature teratoma and contains immature tissues which typically show primitive or embryonal neuroectodermal histopathology. Immature teratoma has one of the lowest rates of somatic mutation of any tumor type and results from one of five mechanisms of meiotic failure.[19]

Gliomatosis peritoneii

[edit]Gliomatosis peritoneii, which presents as a deposition of mature glial cells in the peritoneum, is almost exclusively seen in conjunction with cases of ovarian teratoma. Through genetic studies of exome sequence, it was found that gliomatosis is genetically identical to the parent ovarian tumor and developed from cells that disseminate from the ovarian teratoma.[19]

Dermoid cyst

[edit]A dermoid cyst is a mature cystic teratoma containing hair (sometimes very abundant) and other structures characteristic of normal skin and other tissues derived from the ectoderm. The term is most often applied to teratoma on the skull sutures and in the ovaries of females.[citation needed]

Fetus in fetu and fetiform teratoma

[edit]Fetus in fetu and fetiform teratoma are rare forms of mature teratomas that include one or more components resembling a malformed fetus. Both forms may contain or appear to contain complete organ systems, even major body parts, such as a torso or limbs. Fetus in fetu differs from fetiform teratoma in having an apparent spine and bilateral symmetry.[20]

Most authorities agree that fetiform teratomas are highly developed mature teratomas; the natural history of fetus in fetu is controversial.[20] It has been noted that fetiform teratoma is reported more often (by gynecologists) in ovarian teratomas, and fetus in fetu is reported more often (by general surgeons) in retroperitoneal teratomas. Fetus in fetu has often been interpreted as a fetus growing within its twin. As such, this interpretation assumes a special complication of twinning, one of several grouped under the term parasitic twin. In many cases, the fetus in fetu is reported to occupy a fluid-filled cyst within a mature teratoma.[21][22][23][24] Cysts within mature teratomas may have partially-developed organ systems: reports include cases of partial cranial bones, long bones and a rudimentary, beating heart.[25][26]

Regardless of whether fetus in fetu and fetiform teratoma are one entity or two, they are distinct from and not to be confused with ectopic pregnancy.

Struma ovarii

[edit]A struma ovarii (also known as goitre of the ovary or ovarian goiter) is a rare form of mature teratoma that contains mostly thyroid tissue.[27]

Epignathus

[edit]Epignathus is a rare teratoma originating in the oropharyngeal area that occurs in utero. It presents with a mass protruding from the mouth at birth. Untreated, breathing is impossible. An EXIT procedure is the recommended initial treatment.

Fetal Teratomas

[edit]Teratomas may be found in babies, children, and adults. Teratomas of embryonal origin are most often found in babies at birth, in young children, and, since the advent of ultrasound imaging, in fetuses.

The most diagnosed fetal teratomas are sacrococcygeal teratoma (Altman types I, II, and III) and cervical (neck) teratoma. Because these teratomas project from the fetal body into the surrounding amniotic fluid, they can be seen during routine prenatal ultrasound exams. Teratomas within the fetal body are less easily seen with ultrasound; for these, MRI of the pregnant uterus is more informative.[28][29]

Complications

[edit]Teratomas are not dangerous for the fetus unless either a mass effect occurs or a large amount of blood flows through the tumor (known as vascular steal). The mass effect frequently consists of obstruction of normal passage of fluids from surrounding organs. The vascular steal can place a strain on the growing heart of the fetus, even resulting in heart failure, thus must be monitored by fetal echocardiography.

Pathophysiology

[edit]Teratomas belong to a class of tumors known as nonseminomatous germ cell tumor. All tumors of this class are the result of abnormal development of pluripotent cells: germ cells and embryonal cells. Teratomas of embryonic origin are congenital; teratomas of germ cell origin may or may not be congenital. The kind of pluripotent cell appears to be unimportant, apart from constraining the location of the teratoma in the body.

Teratomas derived from germ cells occur in the testicle and ovaries. Teratomas derived from embryonic cells usually occur on the subject's midline: in the brain, elsewhere in the skull, in the nose, in the tongue, under the tongue, and in the neck (cervical teratoma), mediastinum, retroperitoneum, and attached to the coccyx. Teratomas may also occur elsewhere: very rarely in solid organs (most notably the heart and liver) and hollow organs (such as the stomach and bladder), and more commonly on the skull sutures.

Teratoma rarely include more complicated body parts such as teeth, brain matter,[30] eyes,[31][32] or torso.[33]

Hypotheses of origin

[edit]Concerning the origin of teratomas, numerous hypotheses exist.[20] These hypotheses are not to be confused with the unrelated hypothesis that fetus in fetu (see below) is not a teratoma at all, but rather a parasitic twin.

Diagnosis

[edit]

Teratomas are thought to originate in utero, so can be considered congenital tumors. Many teratomas are not diagnosed until much later in childhood or in adulthood. Large tumors are more likely to be diagnosed early on. Sacrococcygeal and cervical teratomas are often detected by prenatal ultrasound. Additional diagnostic methods may include prenatal magnetic resonance imaging. In rare circumstances, the tumor is so large that the fetus may be damaged or die. In the case of large sacrococcygeal teratomas, a significant portion of the fetus' blood flow is redirected toward the teratoma (a phenomenon called steal syndrome), causing heart failure, or hydrops, of the fetus. In certain cases, fetal surgery may be indicated.

Beyond the newborn period, symptoms of a teratoma depend on its location and organ of origin. Ovarian teratomas often present with abdominal or pelvic pain, caused by torsion of the ovary or irritation of its ligaments. A recently discovered condition where ovarian teratomas cause encephalitis associated with antibodies against the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antibody (NMDAR) - often referred to as "anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis", was identified as a serious complication. Patients develop a multistage illness that progresses from psychosis, memory deficits, seizures, and language disintegration into a state of unresponsiveness with catatonic features often associated with abnormal movements, and autonomic and breathing instability.[34] Testicular teratomas present as a palpable mass in the testis; mediastinal teratomas often cause compression of the lungs or the airways and may present with chest pain and/or respiratory symptoms.

Some teratomas contain yolk sac elements, which secrete alpha-fetoprotein. Its detection may help to confirm the diagnosis and is often used as a marker for recurrence or treatment efficacy, but is rarely the method of initial diagnosis. (Maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein is a useful screening test for other fetal conditions, including Down syndrome, spina bifida, and abdominal wall defects such as gastroschisis.)

Classification

[edit]Regardless of location in the body, a teratoma is classified according to a cancer staging system. This indicates whether chemotherapy or radiation therapy may be needed in addition to surgery. Teratomas commonly are classified using the Gonzalez-Crussi[20] grading system: 0 or mature (benign); 1 or immature, probably benign; 2 or immature, possibly malignant (cancerous); and 3 or frankly malignant. If frankly malignant, the tumor is a cancer for which additional cancer staging applies.[citation needed]

Teratomas are also classified by their content; a solid teratoma contains only tissues (perhaps including more complex structures); a cystic teratoma contains only pockets of fluid or semifluid such as cerebrospinal fluid, sebum, or fat; a mixed teratoma contains both solid and cystic parts. Cystic teratomas usually are grade 0 and, conversely, grade 0 teratomas usually are cystic.

Grades 0, 1, and 2 pure teratomas have the potential to become malignant (grade 3), and malignant pure teratomas have the potential to metastasize. These rare forms of teratoma with malignant transformation may contain elements of somatic (not germ cell) malignancy such as leukemia, carcinoma, or sarcoma.[35] A teratoma may contain elements of other germ cell tumors, in which case it is not a pure teratoma, but rather is a mixed germ cell tumor and is malignant. In infants and young children, these elements usually are endodermal sinus tumor, followed by choriocarcinoma. Finally, a teratoma can be pure and not malignant yet highly aggressive; this is exemplified by growing teratoma syndrome, in which chemotherapy eliminates the malignant elements of a mixed tumor, leaving pure teratoma, which paradoxically begins to grow very rapidly.[36]

Malignant transformation

[edit]A "benign" grade 0 (mature) teratoma nonetheless has a risk of malignancy. Recurrence with malignant endodermal sinus tumor has been reported in cases of formerly benign mature teratoma,[37][38] even in fetiform teratoma and fetus in fetu.[39][40] Squamous cell carcinoma has been found in a mature cystic teratoma at the time of initial surgery.[41] A grade 1 immature teratoma that appears to be benign (e.g., because AFP is not elevated) has a much higher risk of malignancy, and requires adequate follow-up.[42][43][44][45] This grade of teratoma also may be difficult to diagnose correctly. It can be confused with other small round cell neoplasms such as neuroblastoma, small cell carcinoma of hypercalcemic type, primitive neuroectodermal tumor, Wilm's tumor, desmoplastic small round cell tumor, and non-Hodgkin lymphoma.[46]

A teratoma with malignant transformation is a very rare form of teratoma that may contain elements of somatic malignant tumors such as leukemia, carcinoma, or sarcoma.[35] Of 641 children with pure teratoma, nine developed TMT:[47] five carcinoma, two glioma, and two embryonal carcinoma (here, these last are classified among germ cell tumors).

Extraspinal ependymoma

[edit]Extraspinal ependymoma, usually considered to be a glioma (a type of nongerm cell tumor), may be an unusual form of mature teratoma.[48]

Treatment

[edit]Surgery

[edit]The treatment of choice is complete surgical removal (i.e., complete resection).[49][50] Teratomas are normally well-encapsulated and noninvasive of surrounding tissues, hence they are relatively easy to resect from surrounding tissues. Exceptions include teratomas in the brain, and very large, complex teratomas that have pushed into and become interlaced with adjacent muscles and other structures.

Prevention of recurrence does not require en bloc resection of surrounding tissues.

Chemotherapy

[edit]For malignant teratomas, usually, surgery is followed by chemotherapy.

Teratomas that are in surgically inaccessible locations, or are very complex, or are likely to be malignant (due to late discovery and/or treatment) sometimes are treated first with chemotherapy. [citation needed]

Follow-up

[edit]Although often described as benign, a teratoma does have malignant potential. A UK study of 351 infants and children diagnosed with "benign" teratoma reported 227 with MT, 124 with IT. Five years after surgery, event-free survival was 92.2% and 85.9%, respectively, and overall survival was 99% and 95.1%.[51] A similar study in Italy reported on 183 infants and children diagnosed with teratoma. At 10 years after surgery, event-free and overall survival were 90.4% and 98%, respectively.[52]

Depending on which tissue(s) it contains, a teratoma may secrete a variety of chemicals with systemic effects. Some teratomas secrete the "pregnancy hormone" human chorionic gonadotropin (βhCG), which can be used in clinical practice to monitor the successful treatment or relapse in patients with a known HCG-secreting teratoma. This hormone is not recommended as a diagnostic marker, because most teratomas do not secrete it. Some teratomas secrete thyroxine, in some cases to such a degree that it can lead to clinical hyperthyroidism in the patient. Of special concern is the secretion of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP); under some circumstances, AFP can be used as a diagnostic marker specific for the presence of yolk sac cells within the teratoma. These cells can develop into a frankly malignant tumor known as yolk sac tumor or endodermal sinus tumor.

Adequate follow-up requires close observation, involving repeated physical examination, scanning (ultrasound, MRI, or CT), and measurement of AFP and/or βhCG.[53][54]

Epidemiology

[edit]

Embryonal teratomas most commonly occur in the sacrococcygeal region; sacrococcygeal teratoma is the single most common tumor found in newborn humans.

Of teratomas on the skull sutures, about 50% are found in or adjacent to the orbit.[56] Limbal dermoid is a choristoma, not a teratoma.

Teratoma qualifies as a rare disease, but is not extremely rare. Sacrococcygeal teratoma alone is diagnosed at birth in one out of 40,000 humans. Given the current human population and birth rate, this equals five per day or 1800 per year. Add to that number sacrococcygeal teratomas diagnosed later in life, and teratomas in other locales, and the incidence approaches 10,000 new diagnoses of teratoma per year.[citation needed]

Other animals

[edit]Ovarian teratomas have been reported in mares,[57] mountain lions,[58][59] and canines.[60] Teratomas also occur, rarely, in other species.[61]

Use in stem cell research

[edit]Pluripotent stem cells including human induced pluripotent stem cells have a unique property of being able to generate teratomas when injected in rodents in the research laboratory.[62] The roots of this observation has been attributed to Leroy Stevens of the Jackson Laboratory.[63] In 1970, Stevens noticed that the cell populations that gave rise to teratomas were very similar to the cells of very early embryos. For this reason, the so-called "teratoma assay" is one of the gold-standard validation assays for pluripotent stem cells.[64] Because differentiated human pluripotent stem cells are being developed as the basis for numerous regenerative medicine therapies, there is concern that residual undifferentiated stem cells could lead to teratoma formation in injected patients, and researchers are working to develop methods to address this concern.[65]

New research has looked at utilizing the human teratoma in chimeric animal studies as a promising platform for modeling multi-lineage human development, pan-tissue functional genetic screening, and tissue engineering.[66]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Raja SG (2007). Access to Surgery: 500 single best answer questions in general and systematic pathology. PasTest Ltd. p. 508. ISBN 9781905635368.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Sacrococcygeal Teratoma". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). 2007. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ a b Millet I, Perrochia H, Pages-Bouic E, Curros-Doyon F, Rathat G, Taourel P (2014). "CT and MR of Benign Ovarian Germ Cell Tumours". In Saba L, Acharya UR, Guerriero S, Suri JS (eds.). Ovarian Neoplasm Imaging. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 165. ISBN 9781461486336.

- ^ a b c d e f "NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms". National Cancer Institute. 2011-02-02. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Davies M, Inglis G, Jardine L, Koorts P (2012). Antenatal Consults: A Guide for Neonatologists and Paediatricians - E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 298. ISBN 978-0729581080.

- ^ a b c Price P, Sikora K, Illidge T (2008). Treatment of Cancer (Fifth ed.). CRC Press. p. 713. ISBN 9780340912218.

- ^ a b Corton MM, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Hoffman BL (2014). Williams Obstetrics 24/E (EBOOK). McGraw Hill Professional. p. Chapter 16. ISBN 9780071798945.

- ^ a b "Mature teratoma". National Cancer Institute. 2011-02-02. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- ^ Noor MR, Hseon TE, Jeffrey LJ, eds. (2014). "Ovarian Germ Cell Tumors". Gynaecologic Cancer: A Handbook for Students and Practitioners. CRC Press. p. 446. ISBN 9789814463065.

- ^ a b c Falcone T, Hurd WW (2007). Clinical Reproductive Medicine and Surgery. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 749. ISBN 978-0323033091.

- ^ Oyasu R, Yang XJ, Yoshida O (2009). Questions in Daily Urologic Practice: Updates for Urologists and Diagnostic Pathologists. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 253. ISBN 9784431728191.

- ^ Hillard PJ, Hillard PA (2008). The 5-minute Obstetrics and Gynecology Consult. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 140. ISBN 9780781769426.

- ^ Hart I, Newton RW (2012). Endocrinology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 157. ISBN 9789401092982.

- ^ McDougal WS, Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Partin AW, Peters CA, Ramchandani P (2011). Campbell-Walsh Urology (10th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 663. ISBN 978-1455723171.

- ^ Chang AE, Ganz PA, Hayes DF, Kinsella T, Pass HI, Schiller JH, Stone RM, Strecher V (2007). Oncology: An Evidence-Based Approach. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 848. ISBN 9780387310565.

- ^ Makuch M, Wilson R, Al-Diwani A, Varley J, Kienzler AK, Taylor J, et al. (March 2018). "N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antibody production from germinal center reactions: Therapeutic implications". Annals of Neurology. 83 (3): 553–561. doi:10.1002/ana.25173. PMC 5925521. PMID 29406578.

- ^ Choi KW, Jeon WJ, Chae HB, Park SM, Youn SJ, Shin HM, et al. (September 2003). "[A recurred case of a mature ovarian teratoma presenting as a rectal mass]" (PDF). The Korean Journal of Gastroenterology = Taehan Sohwagi Hakhoe Chi (in Korean). 42 (3): 242–245. PMID 14532748.

- ^ Mandal S, Badhe BA (2012). "Malignant transformation in a mature teratoma with metastatic deposits in the omentum: a case report". Case Reports in Pathology. 2012: 568062. doi:10.1155/2012/568062. PMC 3469088. PMID 23082264.

- ^ a b Heskett MB, Sanborn JZ, Boniface C, Goode B, Chapman J, Garg K, et al. (June 2020). "Multiregion exome sequencing of ovarian immature teratomas reveals 2N near-diploid genomes, paucity of somatic mutations, and extensive allelic imbalances shared across mature, immature, and disseminated components". Modern Pathology. 33 (6): 1193–1206. doi:10.1038/s41379-019-0446-y. PMC 7286805. PMID 31911616.

- ^ a b c d Gonzalez-Crussi F (1982) Extragonadal Teratomas. Atlas of Tumor Pathology, Second Series, Fascicle 18. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington D.C.

- ^ Abbott TM, Hermann WJ, Scully RE (1984). "Ovarian fetiform teratoma (homunculus) in a 9-year-old girl". International Journal of Gynecological Pathology. 2 (4): 392–402. doi:10.1097/00004347-198404000-00007. PMID 6724790.

- ^ Saito K, Katsumata Y, Hirabuki T, Kato K, Yamanaka M (2007). "Fetus-in-fetu: parasite or neoplasm? A study of two cases". Fetal Diagnosis and Therapy. 22 (5): 383–388. doi:10.1159/000103301. PMID 17556829. S2CID 57099054.

- ^ Kajbafzadeh AM, Baharnoori M (October 2006). "Fetus in fetu". The Canadian Journal of Urology. 13 (5): 3277–3278. PMID 17076951.

- ^ Chua JH, Chui CH, Sai Prasad TR, Jabcobsen AS, Meenakshi A, Hwang WS (November 2005). "Fetus-in-fetu in the pelvis: report of a case and literature review" (PDF). Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore. 34 (10): 646–649. PMID 16382253.

- ^ Lee YH, Kim SG, Choi SH, Kim IS, Kim SH (December 2003). "Ovarian mature cystic teratoma containing homunculus: a case report" (PDF). Journal of Korean Medical Science. 18 (6): 905–907. doi:10.3346/jkms.2003.18.6.905. PMC 3055135. PMID 14676454. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-22.

- ^ Kazez A, Ozercan IH, Erol FS, Faik Ozveren M, Parmaksiz E (August 2002). "Sacrococcygeal heart: a very rare differentiation in teratoma". European Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 12 (4): 278–280. doi:10.1055/s-2002-34483. PMID 12369008. S2CID 260136953.

- ^ Frysak Z, Schovanek J, Halenka M, Metelkova I, Duskova M, Karasek D (2016). "Ovarian Goiter as a Rare Cause of Hyperthyroidism". Acta Endocrinologica. 12 (3): 335–338. doi:10.4183/aeb.2016.335. PMC 6535264. PMID 31149110.

- ^ Danzer E, Hubbard AM, Hedrick HL, Johnson MP, Wilson RD, Howell LJ, et al. (October 2006). "Diagnosis and characterization of fetal sacrococcygeal teratoma with prenatal MRI". AJR. American Journal of Roentgenology. 187 (4): W350–W356. doi:10.2214/AJR.05.0152. PMID 16985105.

- ^ Kocaoglu M, Frush DP (2006). "Pediatric presacral masses". Radiographics. 26 (3): 833–857. doi:10.1148/rg.263055102. PMID 16702458.

- ^ Shintaku M, Sakuma T, Ohbayashi C, Maruo M (April 2017). "Well-formed cerebellum and brainstem-like structures in a mature ovarian teratoma: Neuropathological observations". Neuropathology. 37 (2): 122–128. doi:10.1111/neup.12360. PMID 28042664. S2CID 25588284.

- ^ Chi JG, Lee YS, Park YS, Chang KY (July 1984). "Fetus-in-fetu: report of a case". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 82 (1): 115–119. doi:10.1093/ajcp/82.1.115. PMID 6540049.

- ^ Sergi C, Ehemann V, Beedgen B, Linderkamp O, Otto HF (1999). "Huge fetal sacrococcygeal teratoma with a completely formed eye and intratumoral DNA ploidy heterogeneity". Pediatric and Developmental Pathology. 2 (1): 50–57. doi:10.1007/s100249900089. PMID 9841706. S2CID 22847474.

- ^ Arlikar JD, Mane SB, Dhende NP, Sanghavi Y, Valand AG, Butale PR (March 2009). "Fetus in fetu: two case reports and review of literature". Pediatric Surgery International. 25 (3): 289–292. doi:10.1007/s00383-009-2328-8. PMID 19184054. S2CID 11210782.

- ^ Dalmau J, Lancaster E, Martinez-Hernandez E, Rosenfeld MR, Balice-Gordon R (January 2011). "Clinical experience and laboratory investigations in patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis". The Lancet. Neurology. 10 (1): 63–74. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70253-2. PMC 3158385. PMID 21163445.

- ^ a b Harms D, Zahn S, Göbel U, Schneider DT (2006). "Pathology and molecular biology of teratomas in childhood and adolescence". Klinische Padiatrie. 218 (6): 296–302. doi:10.1055/s-2006-942271. PMID 17080330. S2CID 20627932.

- ^ Scavuzzo A, Santana Ríos ZA, Noverón NR, Jimenez Ríos MA (2014). "Growing teratoma syndrome". Case Reports in Urology. 2014: 139425. doi:10.1155/2014/139425. PMC 4150507. PMID 25197607.

- ^ Ohno Y, Kanematsu T (October 1998). "An endodermal sinus tumor arising from a mature cystic teratoma in the retroperitoneum in a child: is a mature teratoma a premalignant condition?". Human Pathology. 29 (10): 1167–1169. doi:10.1016/S0046-8177(98)90432-4. PMID 9781660.

- ^ Utsuki S, Oka H, Sagiuchi T, Shimizu S, Suzuki S, Fujii K (June 2007). "Malignant transformation of intracranial mature teratoma to yolk sac tumor after late relapse. Case report". Journal of Neurosurgery. 106 (6): 1067–1069. doi:10.3171/jns.2007.106.6.1067. PMID 17564180. S2CID 23864999.

- ^ Chen YH, Chang CH, Chen KC, Diau GY, Loh IW, Chu CC (May 2007). "Malignant transformation of a well-organized sacrococcygeal fetiform teratoma in a newborn male". Journal of the Formosan Medical Association = Taiwan Yi Zhi. 106 (5): 400–402. doi:10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60326-0. PMID 17561476.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Hopkins KL, Dickson PK, Ball TI, Ricketts RR, O'Shea PA, Abramowsky CR (October 1997). "Fetus-in-fetu with malignant recurrence". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 32 (10): 1476–1479. doi:10.1016/S0022-3468(97)90567-4. PMID 9349774.

- ^ Arioz DT, Tokyol C, Sahin FK, Koker G, Yilmaz S, Yilmazer M, Ozalp S (2008). "Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a mature cystic teratoma of the ovary in young patient with elevated carbohydrate antigen 19-9". European Journal of Gynaecological Oncology. 29 (3): 282–284. PMID 18592797.

- ^ Muscatello L, Giudice M, Feltri M (November 2005). "Malignant cervical teratoma: report of a case in a newborn". European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 262 (11): 899–904. doi:10.1007/s00405-005-0917-2. PMID 15895292. S2CID 11556991.

- ^ Ukiyama E, Endo M, Yoshida F, Tezuka T, Kudo K, Sato S, et al. (July 2005). "Recurrent yolk sac tumor following resection of a neonatal immature gastric teratoma". Pediatric Surgery International. 21 (7): 585–588. doi:10.1007/s00383-005-1404-y. PMID 15928937. S2CID 40147917.

- ^ Bilik R, Shandling B, Pope M, Thorner P, Weitzman S, Ein SH (September 1993). "Malignant benign neonatal sacrococcygeal teratoma". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 28 (9): 1158–1160. doi:10.1016/0022-3468(93)90154-D. PMID 7508500.

- ^ Hawkins E, Issacs H, Cushing B, Rogers P (November 1993). "Occult malignancy in neonatal sacrococcygeal teratomas. A report from a Combined Pediatric Oncology Group and Children's Cancer Group study". The American Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 15 (4): 406–409. PMID 7692755.

- ^ Ramalingam P, Teague D, Reid-Nicholson M (August 2008). "Imprint cytology of high-grade immature ovarian teratoma: a case report, literature review, and distinction from other ovarian small round cell tumors". Diagnostic Cytopathology. 36 (8): 595–599. doi:10.1002/dc.20849. PMID 18618728. S2CID 21066080.

- ^ Biskup W, Calaminus G, Schneider DT, Leuschner I, Göbel U (2006). "Teratoma with malignant transformation: experiences of the cooperative GPOH protocols MAKEI 83/86/89/96". Klinische Padiatrie. 218 (6): 303–308. doi:10.1055/s-2006-942272. PMID 17080331. S2CID 260569521.

- ^ Aktuğ T, Hakgüder G, Sarioğlu S, Akgür FM, Olguner M, Pabuçcuoğlu U (March 2000). "Sacrococcygeal extraspinal ependymomas: the role of coccygectomy". Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 35 (3): 515–518. doi:10.1016/S0022-3468(00)90228-8. PMID 10726703.

- ^ Tapper D, Lack EE (September 1983). "Teratomas in infancy and childhood. A 54-year experience at the Children's Hospital Medical Center". Annals of Surgery. 198 (3): 398–410. doi:10.1097/00000658-198309000-00016. PMC 1353316. PMID 6684416.

- ^ Göbel U, Schneider DT, Calaminus G, Haas RJ, Schmidt P, Harms D (March 2000). "Germ-cell tumors in childhood and adolescence. GPOH MAKEI and the MAHO study groups". Annals of Oncology. 11 (3): 263–271. doi:10.1023/a:1008360523160. PMID 10811491.

- ^ Mann JR, Gray ES, Thornton C, Raafat F, Robinson K, Collins GS, et al. (July 2008). "Mature and immature extracranial teratomas in children: the UK Children's Cancer Study Group Experience". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 26 (21): 3590–3597. doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.16.0622. PMID 18541896.

- ^ Lo Curto M, D'Angelo P, Cecchetto G, Klersy C, Dall'Igna P, Federico A, et al. (April 2007). "Mature and immature teratomas: results of the first paediatric Italian study". Pediatric Surgery International. 23 (4): 315–322. doi:10.1007/s00383-007-1890-1. PMID 17333214. S2CID 1380993.

- ^ Marina NM, Cushing B, Giller R, Cohen L, Lauer SJ, Ablin A, et al. (July 1999). "Complete surgical excision is effective treatment for children with immature teratomas with or without malignant elements: A Pediatric Oncology Group/Children's Cancer Group Intergroup Study". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 17 (7): 2137–2143. doi:10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2137. PMID 10561269.

- ^ Cushing B, Giller R, Ablin A, Cohen L, Cullen J, Hawkins E, et al. (August 1999). "Surgical resection alone is effective treatment for ovarian immature teratoma in children and adolescents: a report of the pediatric oncology group and the children's cancer group". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 181 (2): 353–358. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(99)70561-2. PMID 10454682.

- ^ - Vaidya S, Sharma P, KC S, Vaidya SA (2014). "Spectrum of ovarian tumors in a referral hospital in Nepal". Journal of Pathology of Nepal. 4 (7): 539–543. doi:10.3126/jpn.v4i7.10295. ISSN 2091-0908.

- Minor adjustment for mature cystic teratomas (0.17 to 2% risk of ovarian cancer): Mandal S, Badhe BA (2012). "Malignant transformation in a mature teratoma with metastatic deposits in the omentum: a case report". Case Reports in Pathology. 2012: 568062. doi:10.1155/2012/568062. PMC 3469088. PMID 23082264. - ^ Orbital dermoid cyst at eMedicine

- ^ Catone G, Marino G, Mancuso R, Zanghì A (April 2004). "Clinicopathological features of an equine ovarian teratoma". Reproduction in Domestic Animals = Zuchthygiene. 39 (2): 65–69. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0531.2003.00476.x. hdl:11581/112802. PMID 15065985.

- ^ Artemis Moshtaghian (January 11, 2016). "Deformed Mountain Lion a mystery". CNN. Cable News Network.

- ^ Lefebvre R, Theoret C, Doré M, Girard C, Laverty S, Vaillancourt D (November 2005). "Ovarian teratoma and endometritis in a mare". The Canadian Veterinary Journal. 46 (11): 1029–1033. PMC 1259148. PMID 16363331.

- ^ Gruys E, van Dijk JE (1976). "Four canine ovarian teratomas and a nonovarian feline teratoma". Veterinary Pathology. 13 (6): 455–459. doi:10.1177/030098587601300609. PMID 1006958. S2CID 46250641.

- ^ López RM, Múrcia DB (August 2008). "First description of malignant retrobulbar and intracranial teratoma in a lesser kestrel (Falco naumanni)". Avian Pathology. 37 (4): 413–414. doi:10.1080/03079450802216660. PMID 18622858. S2CID 748134.

- ^ Gutierrez-Aranda I, Ramos-Mejia V, Bueno C, Munoz-Lopez M, Real PJ, Mácia A, et al. (September 2010). "Human induced pluripotent stem cells develop teratoma more efficiently and faster than human embryonic stem cells regardless the site of injection". Stem Cells. 28 (9): 1568–1570. doi:10.1002/stem.471. PMC 2996086. PMID 20641038.

- ^ "A Stem Cell Legacy: Leroy Stevens". The Scientist Magazine®.

- ^ Knoepfler P (2021-01-14). "What is a teratoma? Research & treatment". The Niche. Retrieved 2021-02-07.

- ^ Lee MO, Moon SH, Jeong HC, Yi JY, Lee TH, Shim SH, et al. (August 2013). "Inhibition of pluripotent stem cell-derived teratoma formation by small molecules". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (35): E3281–E3290. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110E3281L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1303669110. PMC 3761568. PMID 23918355.

- ^ McDonald, Daniella; Wu, Yan; Dailamy, Amir; Tat, Justin; Parekh, Udit; Zhao, Dongxin; Hu, Michael; Tipps, Ann; Zhang, Kun; Mali, Prashant (2020-11-25). "Defining the Teratoma as a Model for Multi-lineage Human Development". Cell. 183 (5): 1402–1419.e18. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.018. ISSN 1097-4172. PMC 7704916. PMID 33152263.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from Dictionary of Cancer Terms. U.S. National Cancer Institute.

This article incorporates public domain material from Dictionary of Cancer Terms. U.S. National Cancer Institute.

External links

[edit]- humpath pathology images #2657 Archived 2017-09-01 at the Wayback Machine (Teratomas), #4541 Archived 2017-09-01 at the Wayback Machine (Mature teratoma), #5350 Archived 2017-09-01 at the Wayback Machine (Immature teratoma)

- cystic teratoma at eMedicine (also search EMedicine for all articles containing the word teratoma)