Xochimilco

Xochimilco | |

|---|---|

Trajinera boats at Xochimilco | |

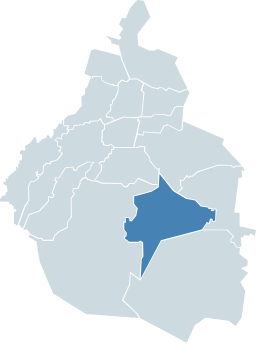

Xochimilco within Mexico City | |

| Coordinates: 19°16′30″N 99°08′20″W / 19.27500°N 99.13889°W | |

| Country | Mexico |

| Federal entity | Mexico City |

| Seat | Av. Guadalupe I, Ramírez 5, Barrio El Rosario Nepantlatlaca, Xochimilco, 16070 |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Zona Centro) |

| Website | xochimilco.cdmx.gob.mx |

| Official name | Historic Center of Mexico City and Xochimilco |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | ii, iii, iv, v |

| Designated | 1987 (11th session) |

| Reference no. | 412 |

| Region | Latin America and the Caribbean |

Xochimilco (Spanish pronunciation: [sotʃiˈmilko]; Classical Nahuatl: Xōchimīlco, pronounced [ʃoːtʃiˈmiːlko] ) is a borough (demarcación territorial) of Mexico City. The borough is centered on the formerly independent city of Xochimilco, which was established on what was the southern shore of Lake Xochimilco in the precolonial period.

Today, the borough consists of the 18 barrios, or neighborhoods, of this city along with 14 pueblos, or villages, that surround it, covering an area of 125 km2 (48 sq mi). The borough is in the southeastern part of the city and has an identity that is separate from the historic center of Mexico City, due to its historic separation from that city during most of its history.

Xochimilco is best known for its canals, which are left from what was an extensive lake and canal system that connected most of the settlements of the Valley of Mexico. These canals, along with artificial islands called chinampas, attract tourists and other city residents to ride on colorful gondola-like boats called trajineras around the 170 km (110 mi) of canals. This canal and chinampa system, as a vestige of the area's precolonial past, has made Xochimilco a World Heritage Site. In 1950, Paramahansa Yogananda, in his Autobiography of a Yogi, wrote that if there were a scenic beauty contest, Xochimilco would get the first prize.[1]

The city and borough

[edit]

The borough of Xochimilco was created in 1928, when the federal government reorganized the Federal District of Mexico City into sixteen boroughs. The Xochimilco borough was centered on what was the city of Xochimilco, which had been an independent settlement from the pre-Hispanic period to the 20th century.[2][3] The area's historic separation from Mexico City proper remains in its culture. While officially part of the city, its identity is more like a suburb.[4] This historic center was designated as a "Barrio Mágico" by the city in 2011.[5] The borough is center-south of the historic center of Mexico City, and bordered by the boroughs of Tlalpan, Coyoacán, Tláhuac and Milpa Alta. It extends over 125 km2 (48 sq mi), accounting for 8.4% of the Federal District's territory. It is the third largest borough, after Tlalpan, and Milpa Alta.[6][7] The borough has an emblem, also known as an Aztec glyph, which is a representation of the area's spongy soil from which two flowering plants emerge.[8] In spite of the serious environmental issues, 77.9% of the territory is designated as ecological reserve, 15.2% as residential and 4.6 as commercial and industrial.[7]

The borough is divided into eighteen “barrios,” which make up the old city of Xochimilco and fourteen communities outside the traditional city called “pueblos.” The barrios are El Rosario, Santa Crucita, Caltongo, San Lorenzo, San Diego, La Asunción, San Juan, San Antonio, Belem, San Cristóbal, San Esteban, La Santísima, La Guadalupita, La Concepción Tlacoapa, San Marcos and Xaltocan, The fourteen pueblos are Santa María Tepepan, Santiago Tepalcatlalpan, San Mateo Xalpa, San Lorenzo Atemoaya, Santa Cruz Xochitepec, San Lucas Xochimanca, San Francisco Tlalnepantla, Santa María Nativitas, San Gregorio Atlapulco, Santiago Tulyehualco, San Luis Tlaxialtemalco, San Andrés Ahuayucan, Santa Cecilia Tepetlapa and San Cruz Acalpixca. There are also 45 smaller divisions called “colonias” and twenty major apartment complexes.[2] The city acts as the local government for all the communities of the borough, whether part of the city or not. These offices are located on Calle Guadalupe I. Ramirez 4, in the El Rosario area.[8] The borough has 11.4 km (7.1 mi) of primary roadway and 4,284,733 square metres (1,058.8 acres) of paved surface.[7] Major thoroughfares include the Xochimilco-Tulyehualco road, Nuevo León, Periférico Sur, Avenida Guadalupe and Calzada México-Xochimilco.[8] However, many of the areas of the borough are still semi-rural, with communities that still retain many old traditions and economic activities. For example, San Antonio Molotlán is noted for textiles and its Chinelos dancers.[9] San Lorenzo Tlaltecpan is known for the production of milk and there are still a large number of stables in the area.[9]

The most notable neighborhoods/communities include Xaltocan, Ejidos de Tepepan, La Noria, Las Cruces, Ejidos de Xochimilco and San Gregorio Atlapulco.[8] San Francisco Caltongo is one of the oldest neighborhoods of the borough.[9] Xaltocán began as a ranch or hacienda that belonged to the indigenous caciques. It was later donated to the San Bernardino de Siena monastery. After the monastery was secularized, it became hacienda land again, but over time, parts were sold and it became the current area of Xochimilco. The church for this community was built in 1751 as the hacienda chapel. Originally, it was dedicated to Jesus, then Candlemas and finally the Virgin of the Sorrows (Virgen de los Dolores). It officially became a sanctuary in 1951, declared by the archbishop of Mexico. In 1964, Xaltocán became a parish and in 1976, this church became the official parish church. The main celebration of the church is to an image of the Virgin Mary, which is said to have miraculously appeared in the pen of a turkey kept by an old woman.[10]

In 2005, the borough had a population of 404,458, 4.6% of the total population of the Federal District. The growth rate is 1.8% for the past decade, lower than the decade previous.[7] However, a large percentage of the borough's population lives in poverty and many live illegally on ecological reserves, lacking basic services such as running water and drainage.[11] In the past, houses in the area were constructed from adobe and wood from juniper trees,[9] but today, most constructions are boxy cinderblock constructions, many of which are not painted.[11] By the 2010 census its population had grown to 415,007 inhabitants, or 4.69% of Mexico City's total.[12]

What was the city of Xochimilco, now sometimes called the historic center of the borough, began as a pre-Hispanic city on the southern shore of Lake Xochimilco. After the Conquest, the Spanish built the San Bernardino de Siena monastery and church, which is still the center of the borough. The main street through the center of town, Guadalupe I.Ramirez, was originally a land bridge connecting this area, then on an island, to the causeway that led to Tenochtitlan (Mexico City). As the lake dried, the bridge became road, and it was called the Puente de Axomulco in the colonial era. It received its current name in the 1970s to honor a delegate of the borough.[13] This town center also has a large plaza and to the side of this, a large area filled with street vendors, many selling ice cream. There is also a “Tianguis de Comida” or market filled with food stalls.[14] This center underwent renovations in 2002 at a cost of sixty million pesos. Drainage and sidewalks were improved and security cameras installed. To improve the area's look for tourists, businesses in the center agreed with the borough and INAH to change their façades to certain colors.[15]

Much of the borough's land is former lakebed. Its main elevations include Xochitepec and Tlacualleli mountains along with two volcanoes named Teutli and Tzompol. It contains two natural rivers called Santiago and Tepapantla along with the various canals, which is what is left of the lake.[6] The elevated areas of the borough contain small forests of ocotes, strawberry trees, cedars, Montezuma cypress and a tree called a “tepozan.”[16]

Xochimilco, along with other southern boroughs such as Milpa Alta and Tlalpan, have lower crime statistics than most other areas of the Federal District. However, crime, especially that related to kidnapping and drug trafficking has been on the rise, and more rural communities have taken to vigilante justice. Residents state that this is necessary because there is insufficient police protection. Xochimilco has only one policeman for each 550 residents on average, and there have been complaints that police have taken over 30 minutes to respond to calls. The borough has a population of 368,798, but only 670 police and 40 police cars. There was one case of vigilante justice in 1999, when a youth accused of robbery was caught and beaten by residents before handed over to police. But the police did not pursue the charge.[17]

The Xochimilco Light Rail line, locally known as El Tren Ligero, of STE, provides light rail service connecting the borough to the Mexico City Metro system.

Canals, chinampas and trajineras

[edit]Lake Xochimilco and the canal system

[edit]

Xochimilco is characterized by a system of canals, which measure about a total of 170 km2.[18] These canals, and the small colorful boats that float on them among artificially created land called chinampas, are internationally famous.[11][19] These canals are popular with Mexico City residents as well, especially on Sundays.[19] These canals are all of what is left of what used to be a vast lake and canal system that extended over most parts of the Valley of Mexico, restricting cities such as Tenochtitlan (Mexico City) and Xochimilco to small islands.[6][20][21] This system of waterways was the main transportation venue, especially for goods from the pre-Hispanic period until the 20th century.[20] In the pre-Hispanic period, parts of the shallow lakes were filled in, creating canals. Starting in the early colonial period, the interconnected lakes of the valley, including Lake Xochimilco, were drained. By the 20th century, the lakes had shrunk to a system of canals that still connected Xochimilco with the center of Mexico City. However, with the pumping of underground aquifers since the early 20th century, water tables have dropped, drying canals, and all that are left are the ones in Xochimilco.[18][20] The canals are fed by fresh water springs, which is artificially supplemented by treated water. This is because water tables are still dropping and human expansion and filling in of canals is still occurring, threatening to have the last of these canals disappear despite their importance to tourism.[11][18][19][20][21]

These remaining canals and their ecosystem was declared a World Heritage Site in 1987, with the purpose of saving them.[22] An important part of this ecosystem is a willow tree called a “ahuejote” that is native to the shallow waters of the lake/canals. These stem erosion, act as wind breakers and favor the reproduction of a variety of aquatic species.[16] Some of these endemic species include a freshwater crayfish called an acocil, and the Montezuma frog.[16][20] However, the most representative animal from these waters is the axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum). This amphibian was used as a medicine, food and ceremonial object during the Aztec Empire. It was considered to be an incarnation of the god Xolotl, brother of Quetzalcoatl. It has been studied due to its abilities to regenerate limbs and other body parts. It can also reach sexual maturity as a larva, which no other amphibian can do. While mostly aquatic, it does have limited ability to breathe air.[23] As of 2003, there were only 600 axolotls known to exist in the wild.[22] Most of the threat to the species is loss of habitat and pollution, but the introduction of non-native fish such as tilapia has also had disastrous effects on the population of this and other species.[22] Conservation efforts include research and environmental education.[23] The Grupo de Investigación del Ajolote en Xochimilco (GIA-X) is a nonprofit research group dedicated to the preservation of the axolotl, which is in danger of extinction. It works to better understand the creature as well as with the local community to protect what is left of its habitat.[24] In addition to species that live in the area year round, the wetlands here host about forty percent of the migratory bird species that arrive to Mexico, roughly 350, use the wet areas around Xochimilco for nesting. Many of these come from the United States and Canada. However, much of this habitat has been urbanized. About 700 species have been found in the area overall. Some of the migratory species include pelicans, storks, buzzards and falcons.[25]

The destruction of the last of these canals began in the 1950s. At that time, groundwater pumping under the city center was causing severe subsidence. These wells were closed and new ones dug in Xochimilco and other southern boroughs. High rates of extraction have had the same effect on water tables and canals began to dry.[26] Since then reclaimed wastewater has been recycled to flow into the Xochimilco canals to supplement water from natural sources. However, this water is not potable, containing bacteria and heavy metals and the canals still receive untreated wastewater and other pollution[27] Another major problem, especially in the past two decades has been the population explosion of Mexico City, pushing urban sprawl further south into formerly rural areas of the Federal District. This prompted authorities to seek World Heritage Site status for the canals and the pre-Hispanic chinampa fields to provide them with more environmental protection.[2][11]

[20] This was granted in 1987,[21] but these same major environmental problems still exist.[11][20] A 2006 study by UNESCO and Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana has shown that there are still very high levels of pollution (both garbage and fecal matter) in the canals and there still a rapid rate of deterioration 2,000 hectares of protected area. UNESCO has placed the most blame for the problems on the proliferation of illegal human settlements in the protected zone.[11][28] Each year the borough loses six hectares of former lakebed to illegal settlements. According to the borough, about 90,000 people in Xochimilco live in illegal settlements, such as those in ecological zones, and 33,804 families live illegally on the chinampas. The most problematic are those closest to the canals, which cause the most pollution.[28] The area is also sinking 18 cm (7.1 in) per year due to over pumping of groundwater, and canals are being filled in illegally.[11] The deterioration is happening so fast, that UNESCO has threatened to pull Xochimilco World Heritage Site status.[11]

Other major problems facing the canal system is the damage by introduced species and disease destroying native ones. Water lilies were introduced to the canals from Brazil in the 1940s. Since then, they have become a serious problem as their overgrowth depletes minerals and oxygen from the water. Up to 400 tons of the plant has been extracted from the canals monthly. In 2006, a Brazilian insect (Anthonomus grandis) was introduced to the canals to help control the plant.[29] However, some need to be maintained because the axolotls are using them for reproduction purposes.[22] Introduced species include carp and tilapia, which were introduced in the 1960s. However, these have been very detrimental to the native ecosystem, especially the axolotl, whose eggs they eat. Despite tons of the fish being caught in the canals, they are still a serious problem.[30] Another major problem is the loss of trees, especially junipers in the ecological zone. Over sixty percent of the area is considered to be serious deforested and eighty percent of the junipers have the parasitic plant mistletoe.[22][31]

Since being declared a World Heritage Site, there have been attempts to rescue the canal system. The first major effort occurred between 1989 and 1994, which was called the “Rescate Ecológico.” It had the goal of constructing a large artificial lake for tourism and sports covering 360 hectares, ten times the size of the lake in Chapultepec Park. These would be divided into two parts called the Ciénega Grande and Ciénega Chica on the side of the Periférico Sur. It would also include the creation of a chinampa zone and areas for culture and commerce and elevated buildings over the two sides of the Periférico Sur similar to those in the San Jerónimo area. However, this plan was stopped by agricultural communities in the area, which have a long history of defending their rights. However, since then, the area has been urbanized. It was replaced by a much smaller lake, with ecological area and plant market.[18] In 2008, borough authorities began a reforestation program over 5,000 hectares of chinampas and forested areas at a cost of 20 million pesos. This program includes the cutting of non native species such as eucalyptus and certain pines and cedars to eradicate plagues associated with them. However, residents near forests such as in Nativitas oppose the cutting of healthy trees. These will be replaced by native species, especially junipers in the chinampa areas.[32] However, it is still estimated that because of the continuance of urban sprawl, the remaining canals and protected land will disappear within fifty years.[18]

Chinampas

[edit]

The canals of Lake Xochimilco were initially created along with artificial agricultural plots called chinampas. Chinampas were invented by the pre-Hispanic peoples of the region around 1,000 years ago as a way to increase agricultural production. On the shallow waters of the lakes, rafts were constructed of juniper branches. Onto these rafts floating on the water, lakebed mud and soil were heaped and crops planted. These rafts, tied to juniper trees, would eventually sink and a new one be built to replace it. Over time, these sunken rafts would form square or rectangular islands, held in place in part by the juniper trees. As these chinampa islands propagated, areas of the lake were reduced to canals. These “floating gardens” were an important part of the economy of the Aztec Empire by the time the Spanish arrived.[33][34][35] Today, only about 5,000 chinampas, all affixed to the lake bottom, still exist in their original form, surrounded by canals and used for agriculture. The rest have become solid ground and urbanized. In the center of Xochimilco, there are about 200 chinampas, covering an area of 1,800 hectares. However, one reason the number has decreased is that smaller chinampas have been combined to create larger ones.[31] While there are still those who maintain chinampas traditionally, and use them for agriculture, the chinampa culture is fading in the borough, with many being urbanized or turned into soccer fields and sites for housing and businesses.[28] The deterioration of many of these chinampas can be seen as their edges erode into the dark, polluted water of the canals.[34] The most deteriorated chinampas are located in the communities of Santa María Nativitas, Santa Cruz Acalpixca, San Gregoria Atlapulco, and Ejido de Xochimilco. Together, these have a total of thirty eight illegal settlements. To repair a number of chinampas, the borough, along with federal authorities, has reinforced 42 km (26 mi) of shoreline, of the 360 km (220 mi) that exist in the lake area. This involves the planting of juniper trees and the sinking of tezontle pylons into the lakebed.[28] These remaining chinampas are part of the Xochimilco World Heritage Site.[34] Have since changed use and become residences and businesses. Those that remain agricultural are mostly used as nurseries, growing ornamental plants such as bougainvilleas, cactuses, dahlias, day lilies, and even bonsai.[36] As they can produce up to eight times the amount of conventional land,[11] they are still an important part of the borough's agricultural production.[34] There have been various attempts to save the remaining chinampas, including their cataloging by UNESCO, UAM, and INAH in 2005, and various reforestation efforts, especially of juniper trees.[22][31]

Island of the Dolls

[edit]

About an hour long canal ride from an embarcadero lies Isla de las Muñecas, or the Island of the Dolls. It is the best-known chinampa, or floating garden, in Xochimilco. It belonged to a man named Don Julián Santana Barrera, a native of the La Asunción neighborhood. Santana Barrera was a loner, who was rarely seen in most of Xochimilco. According to the legend, one early morning a young girl and her sisters went swimming in the canal but the current was too strong. The sisters got separated and the current pulled one of the sisters all the way down the canal when Santana Barrera discovered the young girl while she was drowning. When Santana finally got to her she was already dead. He also found a doll floating nearby and, assuming it belonged to the deceased girl, hung it from a tree as a sign of respect.[37] After this, he began to hear whispers, footsteps, and anguished wails in the darkness even though his hut—hidden deep inside the woods of Xochimilco—was miles away from civilization. Driven by fear, he spent the next fifty years hanging more and more dolls, some missing body parts, all over the island in an attempt to appease what he believed to be the drowned girl's spirit.[38]

After Barrera's death in 2001—his body reportedly found in the exact spot where he found the girl's body fifty years before—the area became a popular tourist attraction where visitors bring more dolls. The locals describe it as "charmed"—not haunted—even though travelers claim the dolls whisper to them. The dolls are still on the island, which is accessible by boat. The island was featured on the Travel Channel show Ghost Adventures and the Amazon Prime show Lore. It was also featured in BuzzfeedUnsolved where Ryan and Shane visited the island with a guide, who lead them around the island during the night. It was also featured on the show Expedition X in season 1 episode 3, where Phil Torres & Jessica Chobot explore the mysteries of the island & the dolls.

History

[edit]

The name "Xochimilco" comes from Nahuatl and means "flower field." This referred to the many flowers and other crops that were grown here on chinampas since the pre-Hispanic period.[6]

The first human presence in the area was of hunter gatherers, who eventually settled into farming communities.[40] The first settlements in the Xochimilco area were associated with the Cuicuilco, Copilco and Tlatilco settlements during the Classic period. The Xochimilca people, considered one of the seven Nahua tribes that migrated into the Valley of Mexico, first settled around 900 BC in Cuahilama, near what is now Santa Cruz Acalpixca. They worshipped sixteen deities, with Chantico, goddess of the hearth; Cihuacoatl, an earth goddess; and Amimitl, god of chinampas, the most important.[2][41]

The Xochimilcas were farmers and founded their first dominion under a leader named Acatonallo. He is credited with inventing the chinampa system of agriculture to increase production. These chinampas eventually became the main producer, with crops such as corn, beans, chili peppers, squash, and more. The city of Xochimilco was founded in 919. Over time, it grew and began to dominate other areas on the south side of the lakes such as Mixquic, Tláhuac, Culhuacan and even parts of what is now the State of Morelos. Xochimilco had one woman ruler, which did not happen anywhere else in Mesoamerica in the pre-Hispanic period. She is credited with adding a number of distinctive dishes to the area's cuisine, with inclusions such as necuatolli, chileatolli (atole with chili pepper), esquites and tlapiques.[2]

In 1352, then emperor Caxtoltzin moved the city from the mainland to the island of Tlilan. In this respect it was like another island city in the area, Tenochtitlan. Although no longer an island, the city center is still in the same spot.[2][6] In 1376, Tenochtitlan attacked Xochimilco, forcing the city to appeal to Azcapotzalco for help. The conquest was unsuccessful, but Xochimilco was then forced to pay tribute to Azcapotzalco. Tenochtitlan succeeded in conquering Xochimilco in 1430, while it was ruled by Tzalpoyotzin. Shortly thereafter, Aztec emperor Itzcoatl built the causeway or calzada that would connect the two cities over the lake. During the reign of Moctezuma Ilhuicamina, the Xochimilcas contributed materials and manpower to construct a temple to Huitzilopochtli. They also participated in the further conquests of the Aztec Empire such as in Cuauhnáhuac (Cuernavaca), Xalisco and the Metztitlán and Oaxaca valleys. For their service, Ahuizotl, granted the Xochimilcas autonomy in their lands, and the two cities coexisted peacefully.[2] Aztec emperors would pass by here on royal barges on their way to Chalco/Xico, then an island in Lake Chalco.[18] For centuries Xochimilco remained relatively separate from Mexico City but provided much of the larger city's produce.[9]

Aztec emperor Moctezuma Xocoyotzin imposed a new governor, Omácatl, onto Xochimilco due to the arrival of the Spanish, but this governor was forced to return to Tenochtitlan, when the emperor was taken prisoner. He was then succeeded by Macuilxochitecuhtli, but eighty days later he too went to Tenochtitlan to fight the Spanish alongside Cuitláhuac. He was followed by Apochquiyautzin, who remained loyal to Tenochtitlan. For this reason, Hernán Cortés decided to send armies to subdue Xochimilco before taking Tenochtitlan. This occurred on 16 April 1521. During the battle, Cortés was almost killed when he fell off his horse, but he was saved by a soldier named Cristóbal de Olea. The battle was fierce and left few Xochimilca warriors alive. The invaders later raped and pillaged the city.[42] According to legend, it was after this battle that Cuauhtémoc came to Xochimilco and planted a juniper tree in the San Juan neighborhood to commemorate the event.[2]

Pre-Hispanic Xochimilco was an island connected to the mainland by three causeways. One of these still exists in the form of Avenida Guadalupe I.Ramirez, one of the city's main streets. This causeway led to the main ceremonial center of the town, which was called the Quilaztli. The Spanish destroyed the Quilaztli during the Conquest, and replaced it with the San Bernardino de Siena Church, which would become the social and political center of the colonial city.[13] The city in turn, was the most important settlement in the south of the Valley of Mexico in the colonial era.[43] It became a settlement of Spanish, criollos and mestizos, with the indigenous living in rural communities outside of the city proper.[6]

During the Siege of Tenochtitlan, Hernán Cortés attacked the city and the "great number of warriors" in it. During the battle, Cortes was knocked from his horse, and almost captured by the Mexicans. The following day, Guatemoc sent ten thousand warriors by land and two thousand by canoe to attack the Spaniards, followed by ten thousand reinforcements. The Mexicans were defeated, and Cortes was able to capture five Mexican captains. Cortes then proceeded with his march.[44]: 340–347

After the Conquest, Apochquiyauhtzin, the last lord of Xochimilco, was baptized with the name of Luís Cortés Cerón de Alvarado in 1522 and he was allowed to continue governing under the Spanish. Evangelization was undertaken here by Martín de Valencia with a number of others who are known as the first twelve Franciscans in Mexico. Their monastery was built between 1534 and 1579, along with many chapels and churches in the Xochimilco area, a hospital in Tlacoapa and a school. Xochimilco was made an encomienda of Pedro de Alvarado in 1521 and remained such until 1541.[2]

The Spanish used the lakes and canals of the Valley of Mexico much as the indigenous did, at least at first.[18] Xochimilco remained an important agricultural area, shipping its produce to Mexico City in the same ways.[9] However, problems with flooding, especially the Great Flood of 1609 in Mexico City and Xochimilco, spurred the Spanish to begin projects to drain the lakes.[2][11] As a result, these lakes, including Lake Xochimilco, has suffered one of the most radical transformations in the history of urbanization. Five hundred years ago, the lake extended 350 km2 (140 sq mi) and contained 170 km2 (66 sq mi) of chinampas and 750 km (470 mi) of canals. Today, there are only 25 km2 (9.7 sq mi) of chinampas and 170 km (110 mi) of canals, and they are still disappearing.[18]

Xochimilco was granted the title of city by Felipe II in 1559. Through much of the colonial era, the city's native population was decimated by epidemics, especially typhoid. Despite this, and because of the apparent acceptance of Christianity, the Xochimilcas were permitted to retain a number of their traditions and their identity as a people. The area remained mostly indigenous for much of the colonial period. Its importance as an agricultural center with easy access to Mexico City meant that in the 17th century, about two thousand barges a day still traveled on the waters that separated the two areas.[2]

In 1749, Xochimilco became a "corregimiento" or semi-autonomous area from Mexico City and would remain so until Independence. It would also increase in importance as a stopover for those traveling between Mexico City and Cuernavaca. Also during this time, Xochimila Martín de la Cruz, wrote Xihuipahtli mecéhual amato, better known as the Aztec Herbal Book or the Cruz-Badiano Codex. It is the oldest book on medicine written on the American continent. It was translated into Latin by Juan Badiano. The original is in the Vatican.[2]

After Independence, Xochimilco became a municipality in what was then the State of Mexico. It would later become a part of the Federal District of Mexico City after the Mexican–American War, when this district was expanded.[2]

Manuel Payno in his novel "Los bandidos del río Frio" related a journey through here between San Lázaro and Chalco.[18] In 1850, the first steam-powered boat traveled through here, connecting Mexico City with Chalco. Steam powered ships remained in Xochimilco waters from then until the 1880s, when they faded from use. Before, during and after, Xochimilco continued to make more traditional rafts, canoes and trajineras, pushed along the shallow waters by a pole.[2]

Up through the centuries, the valley lakes continued to shrink but there were still canals that linked Xochimilco to the center of Mexico City. In the late 19th century, Mexico City had outgrown its traditional water supplies and began to take water from the springs and underground aquifers of Xochimilco.[2][20] Degradation of the lakes was fastest in the early 20th century, when projects such as the Canal del Desagüe were built to further drain the valley.[18] This and excessive aquifer pumping lowered water tables and canals near Mexico City center dried up and cut off an inexpensive way to get goods to market for Xochimilco.[2] This had a major effect on the area's economy, along with the effects of the loss of fishing for communities such as Santa Cruz Acalpixca, San Gregorio Atlapulco and San Luis Tlaxialtemalco.(rescartarlo)[2] In 1908, an electric tram serves was inaugurated that was supposed to reach Tulyehualco, but never did.[2]

During the Mexican Revolution, the first Zapatistas came into the borough through Milpa Alta. They burned areas in Nativitas and San Lucas in 1911 and then stayed without further attacks. They then took the city of Xochimilco in 1912, burning the southern part. The Zapatistas then controlled most of what is now the borough. On 23 April 1913, 39 youths were shot to death in a small alley in San Lucas Xochimanca. A plaque commemorates the site. When the Zapatistas were confronted by troops loyal to Venustiano Carranza in Cuemanco, they damaged pumps and set the center of Xochimilco and the original municipal palace on fire. In 1914, Francisco Villa and Emiliano Zapata met in San Gregorio and signed an alliance called the Pact of Xochimilco.[2]

After the war, Xochimilco became a borough when the Federal District was reorganized, including the communities of Mixquic, San Juan Ixtayopan and Tetelco. These and other territories would be lost and its final dimensions attained in 1931.[2]

In the 1920s, Xochimilco lost control of most of its water supply, taken by the city for its needs.[34] The urban sprawl of Mexico City reached Xochimilco in the mid 20th century and it still affects the borough today.[9] In the 1970s, the federal government began to replace the lost supply to the canals with treated water from the nearby Cerro de la Estrella. This is most of the water that now flows in the canals. The treated water is clear, but not potable due to bacteria and heavy metals. However, it is used to irrigate crops grown on the chinampas, even though the canals are further polluted by untreated sewage and garbage.[34] The biggest threat to the canals and their ecosystem is uncontrolled sprawl, mostly due to illegal building on conservation land. These settlements are polluting canals with untreated garbage and waste, and filling in canals to make "new land."[11] There are thirty-one illegal settlements in the historic center, with 2,700 constructions. Ten of these are in the chinampas of San Gregorio Atlapulco, San Luis Tlaxialtemalco, Santa Cruz Acalpixca, and Santa María Nativitas.[28] The borough and UNESCO are at odds over what to do about the 450 hectares of illegal settlements.[45] UNESCO demands their eviction, but the borough says this would be too difficult and better to legalize the settlements, putting efforts into preventing more.[11][45]

Religion

[edit]

From the pre-Hispanic period to the present, religion has pervaded the life of people in this region.[40] Since it was imposed in the early 16th century, the Catholic religion has permeated and molded popular culture. As in other parts of Mexico, indigenous beliefs and practices, such as those of the Xochimilca, were not completely eradicated. Instead, many were integrated and readapted to Catholicism. One example of this is the building of churches over former temples and other sacred sites. These churches' decorations often have indigenous elements as well.[46] Despite the fact that 91% of the population self identifies as Catholic, there are still many indigenous traditions related to the agricultural cycle.[40][46] A more important syncretism has been the many religious festivals that occur through the year, and the means by which these festivals are sponsored and organized. Much of religious practice in the borough is through symbolic processes that work to produce a kind of social cohesion. The most visible of these are the large civic/religious festivals.[46]

There is some religious plurality in the borough although they represent a very small minority of the population. There are thirty six non-Catholic congregations in the borough with about seventy places of worship. Almost all are Protestant or Evangelical groups established by missionaries, mostly from the United States. The first was established 120 years ago, but most have been established in the last twenty years, with a small but growing number of followers. However, since almost all social activity is related to this popular Catholic festival calendar, intolerance of religious minorities generally takes the subtle form of being excluded from events, although a number of non-Catholics participate in festivities anyway.[46]

These mostly religious festivals and other traditions have been maintain despite the urbanization of the borough. The calendar of celebrations here is extensive. Some are civic or political events such as Independence Day or local celebrations such as the birth of poet Fernando Celada, the birth of Quirino Mendoza y Cortés, composer of “Cielito Lindo,” and the commemoration of the meeting of Francisco Villa and Emiliano Zapata on December 4 in this area. However, most events are tied to religious activity and tradition, organized by volunteers called mayordomos.[47] The mayordomia system is the most important social structure in the borough. The primary task of these volunteers is to sponsor and organized any many religious festivals and celebrations that occur through the year, as well as other duties. This may be paid for by collecting donations or paid for directly by the mayordomo.[4][46] There are 422 officially recognized festivals during the year,[4] including those local to specific communities.[40] One of these more localized festivals is on May 3, Day of the Holy Cross, which has been celebrated in communities such as Santa Cruz Xochitepec (or Magdalena Xochitepec), Santa Cruz Acalpixcan and the center of Xochimilco for over 400 years.[48]

However, the best known mayordomo position is not for a festival, but rather for the care of an image of the child Jesus called the Niñopa.[47] The image is over 435 years old and has a following of about 25,000 in the Xochimilco area.[49] It measures 51 cm (20 in) and weighs less than a kilo.[50] The name “Niñopa” comes from the Spanish word “niño” (child) and the Nahuatl suffix “-pan” (place) to mean “child of the place.”[6] The image was thought to have been made of orange tree wood, but this was proven false when the image was dropped and a finger damaged, allowing for the taking of a small sample. The analysis showed that it was made in the local area of a tree called a chocolín, in the 16th or 17th century.[51] The prestige for becoming a mayordomo for the Niñopa is so great, that the waiting time to become one is decades long.[41][47][51] The mayordomo receives nothing for the care of the image and pays all expenses out of pocket, which includes building rooms for the image to stay, and sponsoring the nearly daily events dedicated to this image.[4] The annual cycle begin on February 2, when the image is received by a new mayordomo. During the year, the image visits homes and hospitals, accompanied by Chinelos dancers.[6] In addition to the Niñopan, other important child Jesus figures include the Niño Dormidito in the Xaltocan neighborhood, the Niño de Belen at the Salitre Embarcadero, the Niño Tamalerito, and the Niño de San Juan. These images, along with the Niñopan, are celebrated together on April 30, at an event called the Niños Sagrados.[41] There are various replicas of the Niñopa, which are owned by former mayordomos.[51]

Fifteen of the eighteen pueblos of Xochimilco hold major events for Day of the Dead, including costume parades, exhibitions, especially of altars, in cemeteries, museums, plazas and more. The Dolores Olmedo Museum has an annual monumental altar to the dead for the occasion As per traditions, the cemeteries of smaller communities such as San Francisco Tlalnepantla, Santa Cruz Xochitepec and Santa María Nativitas are lit with the glow of numerous candles and loved ones sit vigil over the graves.[52] The best known event associated with Day of the Dead is the “la Cihuacoatle, Leyenda de la Llorona,” which is a spectacle based on the La Llorona spectre, which runs from late October to mid November. It takes place on the waters of the old Tlilac Lake. Spectators watch the event from trajineras that depart from the Cuemanco docks and travel the canals to reach the lake. Another similar performance is called “Retorno al Mictlan “or Return to Mictlan, the Aztec land of the Dead, which is performed in the historic center of Xochimilco.[52][53]

After the Conquest, Spaniards began to build churches and monasteries in the various villages in what is now the borough. Typical of these is the monastery at Santa María Tepepan, constructed between 1525 and 1590. Today, Xochimilco has nine parishes and five rectories.[46] The most important of this is also the first church established in the area, the San Bernardino de Siena church and former monastery founded by Martín de Valencia.[54] The current church building was constructed between 1535 and 1590 under the direction of Francisco de Soto, but the cloister and monastery area were not finished until the early 17th century.[46][54] In 1609, a monastery school was founded at the site with classes in rhetoric, theology and arts and letters. Most of the funding of the project came from indigenous leaders of the area, especially Martín Cerónde de Álvaro. In 1538, the Church wanted to bring the complex's Franciscans into Mexico City, but the local people opposed and won. However, in 1569, there were still only four monks serving over 5,000 native people. Soon after, the indigenous population was organized into neighborhoods for indoctrination and census purposes: Santiago Tepalcatlalpan, San Lucas Xochimanca, San Mateo Pochtla, San Miguel Topilejo, San Francisco Tlalnepantla, San Salvador Cuautenco, Santa Cecilia Ahuautla, San Andrés Ocoyoacac, San Lorenzo Tlatecpan, San Martín Tiatilpan, Santa Maria Nativitas Zacapan y Santa Cruz Acalpixcan.[55] Major restoration work was done on the church in its decorative elements in the 1970s. This also included removing two schools that had been established on the large atrium area as well as banning commercial activities from the same.[55]

The church maintains is very large atrium, which was common to monasteries during the evangelization efforts of the very early colonial period. These atriums were meant to hold large congregations of indigenous peoples, who were ministered to by very few monks. The side gate of the atrium has a mixture of Plateresque, Gothic and indigenous feature. The west gate has three arches, which represent the Spanish, indigenous and mestizo peoples of the area. This was the space where the first baptisms of the indigenous were done.[43][55] The church/monastery complex is tall and has a fortress appearance, again something common for the time period.[54]

The church interior conserves its original 16th-century main altar, with four stories tall, contains indigenous, Italian, Flemish and Spanish influence and is covered in 24karat gold leaf.[54] It contains a relief of San Bernardino surrounded by two groups of indigenous sculptures, who are helping to build the church. Above San Bernardino, there is a depiction of the Virgin of the Assumption and the Virgin of Xochimilco. The paintings represent episodes from the life of Jesus and have been attributed to Simon Pereyns and Andrés de la Concha.[43] This is one of the few 16th-century altarpieces to have survived and the only one similar to it in size and construction is located in the monastery in Huejotzingo, Puebla.[55]

There are seven other altarpieces, which date from the 16th to the 18th centuries. The one dedicated to Christ on the north side is from the 16th century, but it is incomplete at its base and sides. The one dedicated to the Holy Family dates from either the 17th or 18th century. Another dedicated to Christ on the south side is from the 16th or 17th century. One dedicated to Martin de Porres is notable because it has no columns.[43][55]

The church's only chapel serves as a tabernacle. This room contains a large painting of Calvary.[43] There are also a large number of notable paintings by names such as Echave Orio, Simón Pereyns, Sánchez Salmerón Caravaggio, Francisco Martínez, Luis Arciniegas and Juan Martínez Monteñés.[55] The baptismal fonts are decorated in acanthus leaves, among which is a pre-Hispanic style skull. The organ is Baroque from the 17th century.[54] The pews are made of red cedar as are the two pulpits, all made by Juan Rojas in the 18th century.[55]

The San Pedro Tlalnahuac Church was one of the first “poza” chapels (used for processions) built in Xochimilco, dating from 1533. The main church has a masonry façade. In front, a small paved yard contains a cross sculpted in wood and sandstone. A significant number of pre-Hispanic artifacts have been found on the grounds. It is located on Calle Pedro Ramírez del Castillo.[43][56]

The La Asunción Colhuacatzinco Church is Neoclassical with arches serving as buttresses. It main altar is modern, from the end of the 20th century. This church is important due to its association with a number of traditions including the Burning of Judas on Easter Sunday and fireworks on frames called toritos. Good Friday is dedicated to the Holy Burial, with mayordomos sponsoring breakfast. It is located in the La Asunción neighborhood.[43][57]

The Santa Crucita de Analco Church was first built in 1687 then rebuilt in Neoclassical style in 1860. Its main altar is modern. It has a chapel in which a number of films have been shot including one called María Candelaria.[43]

The San Juan Bautista Tlateuhchi Church is fronted by a large juniper tree said to have been planted by Cuauhtémoc to commemorate the alliance of the Xochimilas with the Aztecs to fight the Spanish. The church has been through a number of restorations. It is located in the historic center of Xochimilco.[43][56]

The Santa María de los Dolores Xaltocan Church is a Neoclassical building but its main altar is Plateresque and Baroque. This church is hosts a 20-day celebration of Carnival long with the surrounding neighborhoods and markets.[43]

The Belem Church in the historic center dates from 1758. It has been renovated several times, with the last time in 1932.[43]

The La Concepción de María Tlacoapa Church was originally part of a hospital, built by the Franciscans in the 17th century.[43]

The El Rosario Nepantlatlaca is a chapel unique to the area, as its façade is decorated with tiles. It contains a notable painting of Saint Christopher from the 17th century. Originally, the chapel was dedicated to Saint Margaret. It was declared a Historic Monument in 1932.[43]

The Francisco Caltongo Church is one of the farthest from the historic center of the borough in the Caltongo neighborhood. Its façade has a number of pre-Hispanic elements even though it was built in 1969.[43]

The La Santisima Trinidad Chililico Church is noted for its equestrian statue of Saint James as well as its collection of documents related to Xochimilco's history. It is located in the La Santisima neighborhood.[43]

The San Esteban Tecpanpan Church was built on the site of a pre-Hispanic palace and ceremonial center. The current building was constructed in the middle of the 19th century. This building lost its original vault, but it was rebuilt in 1959 along with the bell tower. It is located in the San Esteban neighborhood.[43]

The San Cristóbal Xalan Church is located in the San Cristóbal neighborhood, which is known for floriculture, including poppies that were brought from Europe. Since it blooms in spring, there was a day dedicated to the red poppy called the “Lunes de amapolas,“ which is the day after Easter Sunday. However, this tradition ended when poppy cultivation was banned in 1940.[43]

The San Lorenzo Tlaltecpan Church is located in the San Lorenzo neighborhood, once known for its fishermen. They still specialize in a tamale with fish.[43]

Non-religious festivals

[edit]

There are forty nine important mostly secular festivals through the year, with the most important being the Feria de la Nieve, Feria de la Alegría y el Olivo, and the Flor más Bellas del Ejido.[17] The “Flor más Bella del Ejido” (Most Beautiful Flower of the Ejido or Field) pageant is a borough-wide event dedicated to the beauty of Mexican indigenous women.[6] The origins of this event are traced back over 220 years with symbolism that is based on the pre-Hispanic notion of a “flower-woman” representative of Mother Earth and fertility. This flower-woman is based on the goddess Xochiquetzal, the goddess of flowers and love, robbed from her husband Tlaloc by Tezcatlipoca. After the Conquest, this “flower-woman” symbol survived and would appear at certain Catholic festivals such as the Viernes de Dolores, or the Friday before Palm Sunday. An official pageant dedicated to this was established in 1786. Originally, its purpose was religious but it eventually became secularized. For this reason, the event was moved to a week before the Viernes de Dolores and then called the Viernes de las Amapolas. The event existed in this form for 170 years, with dancing, food, pulque, charros and pageants featuring china poblanas. In 1902, the tradition diminished as the last of the canals connecting the area with the Jamaica market closed. In 1921, the El Universal newspaper held a beauty pageant for the 100th anniversary of the end of the Mexican War of Independence, calling it “La India Bonita” dedicated to indigenous women. The first winner was María Bibiana Uribe. In 1936, another pageant was created for mestizo women called “la Flor Más Bella del Ejido” or the Most Beautiful Flower of the Ejido, which occurred each year on the Viernes de Dolores in the Santa Anita area. This event was moved to San Andres Mixquic in the 1950s, but the lack of crowds had it move again in 1955 to Xochimilco, where it remains.[58]

The Feria de Nieve (Ices and Ice cream Fair) takes place in Santiago Tulyehualco each April. Flavored snow was consumed in the pre Hispanic period, eaten by the rich and made from snow from the nearby mountains and transported through this area. The consumption of this flavored snow continued into the colonial era and the first fair dedicated to it was established in 1529 by Martín de Valencia. The fair was celebrated sporadically until 1885 when there was renewed interest in it, making it an annual event. In 2009, the event had its 124th anniversary. During this time, new flavors and types of frozen confections have been invented. Some of the flavors are uncommon, such as rose petal, pulque, mole, spearmint, lettuce, shrimp and tequila. Many of these were developed by local resident Faustino Cicilia Mora.[59]

The community of Santiago Tepalcatlalpan holds an annual corn festival, as it is still a significant producer of this crop. This event is called the Feria del Maiz y la Tortilla (Corn and Tortilla Fair) in May. It focuses on the traditional methods of preparing and eating the grain, such as in tortillas, gorditas, sopes, quesadillas, tlacoyos with various fillings and atole, especially a version flavored with chili peppers.[60]

The Feria de la Alegría y el Olivo (“Alegria” and Olive Fair) has been an annual event since the 1970s in Santiago Tulyehualco. It is mostly based on a grain native to Mexico called amaranth. An “alegria” is a sweet made with this grain, honey with dried fruits and nuts sometimes added. However, the term is also used to refer to the plant that produces amaranth. An “olivo” is an olive tree. Amaranth was an important part of the pre-Hispanic diet, due to its nutritive qualities and its use in various ceremonies. This annual fair is dedicated to elaboration of this sweet along with olive products from the area.[61] Over 250 producers of the grain offer their products in various preparations. There are also cultural events such as concerts.[62]

The Feria Nacional del Dulce Cristalizado (National Crystallized Candy Fair) takes place each year in the Santa Cruz Acalpixca community at the Plaza Civica. This fair is dedicated to a traditional sweet of various fruits and sometimes plants, which are conserved in a sugar solution until they crystallize. These include squash, pineapple, nopal cactus, tomatoes, chili peppers, figs and more. These traditional sweets are often sold alongside others such as coconut confections, palanquetas de cacahuate (similar to peanut brittle), and nuez con leche (a nut-milk confection). These candies are the result of a blending of pre-Hispanic and European sweet traditions. The main European contributions are sugar and milk products, which are often mixed with native or other introduced ingredients. Originally, fruits and other foods were crystallized this way for conservation. Many in the community of Santa Cruz Acalpixca specialize in the making of one or more of these sweets, which began in 1927 with two shops belonging to Santiago Ramírez Olvera and Aurelio Mendoza in the Tepetitla neighborhood. In the 1980s, the town decided to hold an annual fair to promote their products, which originally was held in conjunction with the festival to the local patron saint. The event includes prizes for the best confections in several categories and the introduction of new types of candies.[63]

Other events include the Carnival of Xochimilco, which was begun in 2004, to rescue the carnival tradition in the area. It consists of a series of musical concerts of various types, art exhibits, food and crafts displays and plays for children.[64] There are also fairs dedicated to rabbits and poinsettias, as well as local civic celebrations to honor events such as the birth of poet Fernando Celada, the birth of Quirino Mendoza y Cortés, composer of “Cielito Lindo,” and the commemoration of the meeting of Francisco Villa and Emiliano Zapata on December 4 in this area.[47]

Xochimilco has also traditionally held the Oktoberfest at the Club Alemán, which is located in the borough.

In Xochimilco was made film Sin Azul. Úrsula Murayama appeared in that film as Laura.[65]

Economy

[edit]Since the pre-Hispanic period, Xochimilco's economy has traditionally been based on agriculture, mostly by supplying to the needs of Mexico City. This not only dominated the economy but also the area's religious practices, some of which can still be seen to the present day.[9][34][46] Agriculture still remains important in the borough, but most of the focus has shifted to flowers and ornamental plants. One major reason for this is the poor quality of the area's water supply.[9][34] Xochimilco has four major markets dedicated to the sale of plants and flowers: Cuemanco, Palacio de la Flor, Mercado de Madre Selva and the historic market at San Luis Tlaxialtemalco. Cuemanco is the largest in Xochimilco and the largest of its kind in Latin America, covering thirteen hectares, with its own cactus garden and forms part of the ecological preserve of Cuemanco.[14][66][67] The borough produces 2.5 million poinsettias each year, accounting for most of the 3.5 million sold each year in Mexico City. This represents an income for the borough of about 25 to 30 million pesos annually, grown by about 10,000 growers.[68]

However, starting in the later 20th century, most of area's economy has shifted away from agriculture.[46] One reason for this is the deterioration of the area's environment. Plagues and poor planning have gravely affected the conservation area in Xochimilco, to the extent that many fruit trees traditionally grown here have disappeared, including capulins and peaches.[32] Over the last forty years, the percentage of people in the borough working in agriculture has dropped from forty percent to three percent.[34]

Xochimilco still has 3,562 units of agricultural production, accounting for 17.7% of the total of the Federal District. These cover 2,741.4 hectares of land or 11.4% of the District. 2741.4 hectares is farmland, with a much smaller amount dedicated to fishing and forestry. Xochimilco accounts for 90.8 percent of the flower production of the District, 76.9% of poinsettias, and all of the geraniums and roses grown here. It also grows about 40% of the District's spinach crop, 24.6 of the figs, 8.7 of pears, 13.2 of pears and 9% of plums. As a producer of livestock, Xochimilco accounts for 36% of the cattle, 29.8% of the pig, 17.2 of sheep and 27.8% of the domestic fowl production of the District.[7]

Most of the employed are in manufacturing (23.5%) commerce (39,7%) and services (33.3%). Over 91% of all businesses in the borough are related to commerce and services. However, manufacturing contributes to 61.8% of the borough GDP, with commerce at 18.9% and services at 18%.[7] After agriculture, the most visible economic activity is tourism, which is considered part of commerce and services. The canals, chinampas and trajineras are the borough's main tourist attraction.[2] In February 2011, trajinera operators protested the existence of “clandestine” tour operators supposedly tolerated by authorities. There are supposedly as many as twenty five or thirty of these who pay bribes of 500 pesos a month to operate away from the six embarcaderos authorized by the borough.[69] Relative to the rest of the city, Xochimilco has a negligible amount of hotel infrastructure. There are no five star hotels. There are 183 four-star and 98 three-star hotels, but they represent only two percent and one percent respectively of the total for the city.[7]

Other landmarks

[edit]

Aside from the canals and trajineras, the best-known attraction in Xochimilco is the Dolores Olmedo Museum.[67] This museum was once the home of socialite Dolores Olmedo. Before this, it was the main house of the La Noria Hacienda, established in the 17th century. Before she died, Ms. Olmedo decided to donate her house, much of what was in it and her art collection to the public as a museum. The buildings are surrounded by gardens planted with native Mexican species, around which wander peacocks. Another area houses a number of xoloitzcuintle dog.[14][67] The museum's collection includes about 600 pre Hispanic pieces, the largest collection of works by Diego Rivera at 140 pieces, as well as a number of works by Frida Kahlo and Angelina Beloff. It also contains rooms filled with furniture, items from many parts of the world and everyday items used by Olmedo and her family.[8][14][67] In November, the museum set up a monumental altar to the dead.[67]

The Museo Arqueológico de Xochimilco (Archeological Museum of Xochimilco) began as a collection of pre-Hispanic artifacts such as ceramics, stone items, bones, and more that had been found in the area, often during construction projects. In 1965, the museum began to display these items to the public. In 1974, the collection moved permanently to a late 19th-century house, which was restored in the 1980s and inaugurated under its current name. This collection contains 2,441 pieces, mostly ceramic and stone objects, including figures, cooking utensils, arrowheads.[70] It is located on Avenida Tenochtitlán in Santa Cruz Acalpixca. Located to one side is one of the fresh water springs that feed the canals. On the other sides are gardens.[71]

Near the archeological museum is a site called Cuahilama. It is a hill that rises about fifty meters above the lakebed. The site consists of terraces and twelve petroglyphs that date to about 1500. The most important of these is called the Nahualapa, a map that contains the locations of 56 sources of water, Lake Xochimilco, eight buildings and a large quantity of roads and paths.[6][56]

As much of the borough is still classified as an ecological reserve, there are a number of green areas open to the public.[71] These include several “forests” such as the Bosque de Nativitas, the Xochimilco Ecological Reserve, the Centro Acuexcomatl, and Michmani Ecotourism Park.[6] There are several parks designated as forests such as the Bosque de Nativitas and the Bosque de San Luis Tlaxialtemaco. These are considered “areas of environmental value” by the city and established to counter some of the damage caused by urban sprawl in Xochimilco. These areas are open to the public but with minimal services such as picnic tables and horseback riding.[72] The largest ecological area is the Xochimilco Ecological Reserve, inaugurated in 1993. It covers over 200 hectares and is filled with numerous plant and animal species that live or migrate here. The park also contains a bike path, thirty five athletic fields, a flower market and a visitor center. It is second in size only to Chapultepec Park. It is also possible to travel in some of the canals here by trajinera.[19][56] The Centro de Educación Ambiental Acuexcomatl (Acuexcomatl Environmental Education Center) is located on the road between Xochimilco center and Tulyehualco.[14] It contains fish farms, beekeeping, plant nurseries and greenhouses as well as sports facilities, classrooms, workshops, an auditorium, an open-air theatre and a cafeteria. It is in Colonia Quirino Mendoza.[16] Michmani is an ecotourism program sponsored by the borough, which is situated on fifty hectares of chinampas. The site offers kayaking, recreational fishing, a temazcal, cabin rentals and environmental education.[72][73]

The crater of the Teoca volcano has a sports facility with jai alai, gymnasiums and a soccer field.[56]

The Virgilio Uribe rowing course was built for the 1968 Olympics in one of the canals. It measures 2,000m long and 125 meters (410 ft) wide. It is still used for canoeing, kayaking, and rowing.[56]

Education

[edit]

The borough contains 116 preschools, 128 primary schools, 48 middle schools, four technical high schools and 15 high schools that serve a student population of over 100,000 students. 4.6 percent of the population is illiterate, lower than the city average. The highest percentage of illiterate people consists of those over sixty years of age. The lowest is in the 15-19-year-old bracket.[7]

Post-secondary education

[edit]The Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana was established in 1974 in Xochimilco under Mexican president Luis Echeverría to meet the growing demand for public university education in the city. Currently, the institution has three campuses in the Federal District, in Azcapotzalco, Iztapalapa and Xochimilco and it is composed of several academic divisions. These divisions include the División de Ciencias y Artes para el Diseño, División de Ciencias Biológicas y de la Salud and the División de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades. The institution offers about twenty bachelor's degrees, an equal number of master's and doctorate degrees as well as a number of certificate programs.[74]

The Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas (National School of Fine Arts) was originally established as the San Carlos Academy in the historic center of Mexico City during the late colonial era in 1781. The school became the most prestigious art academy in Mexico after Independence in the 19th century. In 1910, the school was incorporated into the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. In the 1970s, the school divided into an undergraduate and graduate division and in 1979, the undergraduate division moved to a new campus in Xochimilco, leaving the graduate studies at the traditional site in the historic center.[75] ENAP remains as the country's largest and most prestigious art education institution.[76]

Primary and secondary schools

[edit]National public high schools of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) Escuela Nacional Preparatoria include:

Public high schools of the Instituto de Educación Media Superior del Distrito Federal (IEMS) include:[78]

The Colegio Alemán Alexander von Humboldt has its Campus Sur/Campus Süd (formerly Campus Xochimilco) in the district. The Kindergarten and primary levels occupy the Plantel Tepepan in Colonia Tepepan and the secondary and preparatory levels occupy the Plantel La Noria in Colonia Huichapan (La Noria).[79]

Film Culture

[edit]As Panchito Pistoles Rooster, Jose Carioca Parrot & Donald Duck in a Magic Parcellates Silk in Walt Disney's The Three Caballeros 1944.

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Chapter 21: We Visit Kashmir". Autobiography of a Yogi. Self Realization Fellowship.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "Breve Historia de Xochimilco" [Brief history of Xochimilco] (in Spanish). Xochimilco, Mexico City: Borough of Xochimilco. Archived from the original on October 9, 2018. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ "Historia de la Delegación" [History of the Borough] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Cuauhtémoc. Archived from the original on May 15, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Moffett, Matt (September 7, 1993). "A Partying Town: Mexico's Xochimilco Is Always Celebrating --- Yearlong Fete for Baby Jesus Is the Biggest of 422 Fiestas; The 'Mayordomo' Presides". Wall Street Journal. New York. p. A1.

- ^ Quintanar Hinojosa, Beatriz, ed. (November 2011). "Mexico Desconocido Guia Especial:Barrios Mágicos" [Mexico Desconocido Special Guide:Magical Neighborhoods]. Mexico Desconocido (in Spanish). Mexico City: Impresiones Aereas SA de CV: 5–6. ISSN 1870-9400.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "La magia del Sur del Distrito Federal: Xochimilco" [The magic of the South of the Federal District: Xochimilco] (in Spanish). Xochimilco, Mexico City: Borough of Xochimilco. Archived from the original on October 9, 2018. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Delegación Xochimilco" [Borough of Xochimilco] (PDF) (in Spanish). Mexico City: Secretaría de Desarrollo Económico. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 14, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "Xochimilco" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Government of Mexico City. Archived from the original on October 9, 2018. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Jiménez González, p 54.

- ^ "La Fiesta de Xaltocan Nuestra Señora de los Dolores" [The Festival of Xaltoccan, Our Lady of the Sufferings] (in Spanish). Xochimilco, Mexico City: Borough of Xochimilco. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Cevallos, Diego (November 30, 2004). "Archeology: Mexico's 'Venice' imperiled by pollution and erosion". Global Information Network. New York. p. 1.

- ^ "2010 census tables: INEGI". Archived from the original on May 2, 2013.

- ^ a b "Las calles de Mexico: Calzada prehispanica" [The streets of Mexico: pre Hispanic causeway]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. July 12, 2006. p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e Martinez, Myrna I (April 8, 2009). "Ofrecen escape a la naturaleza" [Offers escape to nature]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 6.

- ^ Hernandez, Jesus Alberto (October 14, 2002). "Renuevan Xochimilco" [Renewing Xochimilco]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 6.

- ^ a b c d Sandoval Ayala, Gualberto (2009). "Xochimilco, el lugar donde moran las flores" [Xochimilco, the place where flowers dwell] (Press release) (in Spanish). SEMARNAT. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b Fernandez, Leticia (December 12, 2004). "Enfrentan pueblos alta desproteccion" [Communities confront high levels of neglect]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Legorreta, Jorge (June 12, 2005). "Xochimilco, ante la última oportunidad para rescatarlo" [Xochimilco, before the last opportunity to rescue it]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Xochimilco" (in Spanish). Mexico City: Mexico Desconcido magazine. 19 July 2010. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mabel, Gloria (2010). "Xochimilco: La lucha por la supervivencia" [Xochimilco: The struggle for survival] (Press release) (in Spanish). SEMARNAT. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Historic Centre of Mexico City and Xochimilco". UNESCO. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Sanders, Nadia (May 29, 2003). "Salvan flora y fauna de la zona lacustre" [Saving flora and fauna of the lake area]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 7.

- ^ a b "Axolotl, Ajolote Ambystoma mexicanum" (in Spanish). Xochimilco, Mexico City: Borough of Xochimilco. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ "Introducción" [Introduction] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Grupo de Investigación del Ajolote en Xochimilco (UNAM). Archived from the original on November 24, 2010. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ Valdez, Ilich (July 30, 2006). "Arriban a suelo xochimilca más de 350 especies de aves" [More than 350 species of birdes arrive to Xochimilco soil]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 4.

- ^ National Research Council Staff, p 14.

- ^ National Research Council Staff, p 36,49.

- ^ a b c d e Valdez, Ilich (August 27, 2006). "'Matan' invasiones a zona chinampera" [Invasions "kill" chinampa zone]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 4.

- ^ Valdez, Ilich (October 28, 2006). "Limpian Xochimilco con insectos de Brasil" [Cleaning Xochimilco with insects from Brazil]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 3.

- ^ Valdez, Ilich (August 5, 2006). "Pesca Xochimilco plaga de tilapias" [Xochimilco fishes a plague of tilapias]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 6.

- ^ a b c Robles, Johana (May 2, 2007). "Grave desforestacion en Xochimilco; [Source: El Universal]" [Grave Deforestation in Xochimilco]. NoticiasFinancieras (in Spanish). Miami. p. 1.

- ^ a b Cruz Flores, Alejandro (June 8, 2008). "Autoridades lanzan programa para rescatar flora tradicional de Xochimilco" [Authorities launch program to rescue the traditional flora of Xochimilco]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ "Las Chinampas" (in Spanish). Xochimilco, Mexico City: Borough of Xochimilco. Archived from the original on June 21, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Puente, Claudia Paz; Adriana Casas; Jorge González; Ana Cecilia Silva (December 9, 2007). "Xochimilco: El ocaso de un paraíso" [Xochimilco: The decline of a paradise]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 18.

- ^ "Los Canales" [The canals] (in Spanish). Xochimilco, Mexico City: Borough of Xochimilco. Archived from the original on December 15, 2018. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ Dews, Charles (January 1, 2003). "Xochimilco – Up A Lazy River In Mexico City". MexConnect newsletter. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ "Isla de las Muñecas – The Island of the Dolls".

- ^ Bender, Jeremy. "There's a small island in Mexico that's inhabited by creepy decaying dolls". Business Insider. Retrieved 2020-12-30.

- ^ Flores Farfán, Sebastián (April 17, 2001). "Murió el señor de las Muñecas de Xochimilco" [The man of the Dolls of Xochimilco died] (in Spanish). Xochimilco, Mexico City: Borough of Xochimilco. Archived from the original on May 18, 2012. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Colores, aromas y sonidos" [Colors, aromas and sounds] (in Spanish). Xochimilco, Mexico City: Borough of Xochimilco. Archived from the original on December 15, 2018. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c Diaz Munoz, Ricardo; Maryell Ortiz de Zarate (March 14, 2004). "Encuentros con Mexico / Los Ninos Dios de Xochimilco (II)" [Encounters with Mexico/The God Children of Xochimilco (II)]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 5.

- ^ Acapantzingo: tierra florida de historia y tradiciones (in Spanish). Instituto de Cultura de Morelos. 1999.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "I g l e s i a s de X o c h i m i l c o" [Churches of Xochimilco] (in Spanish). Xochimilco, Mexico City: Borough of Xochimilco. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ Diaz, B., 1963, The Conquest of New Spain, London: Penguin Books, ISBN 0140441239

- ^ a b Sosa, Ivan (November 20, 2004). "Exige la UNESCO blindar Xochimilco" [UNESCO demands the protection of Xochimilco]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Landázuri Benítez, Gisela; López Levi, Liliana (January 2004). "Tolerancia religiosa en Xochimilco" [Religious tolerance in Xochimilco]. Política y cultura (in Spanish) (21): 141–160.

- ^ a b c d "Las fiestas en Xochimilco" [The Festivals of Xochimilco] (in Spanish). Xochimilco, Mexico City: Borough of Xochimilco. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ "Las Fiestas de la Cruz del tres de Mayo Santa Cruz Xochitepec" [The Festivals of the Cross of May 3 Santa Cruz Xochitepec] (in Spanish). Xochimilco, Mexico City: Borough of Xochimilco. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ Luna, Enrique (February 2, 2011). "Xochimilco festeja al Niñopa" [Xochimilco celebrates the Niñopa]. Uno Mas Uno (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ Carrasco, Sandra (January 30, 2011). "Conoce más sobre el Niño Pa de Xochimilco" [Get to know the Niño Pa better]. El Universal (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c Cordero López, Rodolfo. "Niñopa: Representación de amor y fe" [Niñopa: Representation of love and faith] (in Spanish). Xochimilco, Mexico City: Borough of Xochimilco. Archived from the original on September 8, 2009. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b Inzunza, Anayansin (October 30, 2003). "Arranca el festejo de los muertos en Xochimilco" [Festival of the dead starts up in Xochimilco]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 2.

- ^ "Xochimilco: Un lamento entre trajineras" [Xochimilco: A lament among trajineras]. Mural (in Spanish). Guadalajara, Mexico. October 24, 2004. p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e Diaz Munoz, Ricardo; Maryell Ortiz de Zarate (January 2, 2002). "Encuentros con Mexico / La fiesta continua" [Encounters with Mexico/The party continues]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f g González Guinea, Mara. "Historia del Convento y Parroquia de San Bernardino de Siena" [History of the Monastery and Parish of San Bernardino de Siena] (in Spanish). Xochimilco, Mexico City: Borough of Xochimilco. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Jiménez González, p 57.

- ^ Jiménez González, p 57-58.

- ^ "Fiesta de la Flor más Bella del Ejido 2008" [Festival of the Flor más Bella del Ejido 2008] (in Spanish). Xochimilco, Mexico City: Borough of Xochimilco. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ "FCXXIV Edición de "La Feria de la Nieve" Santiago Tulyehualco Del 4 al 12 de abril" [FCXXIV Edition of the Feria of Ices and Ice Cream Santiago Tulyehualco from 4 to 12 April] (in Spanish). Xochimilco, Mexico City: Borough of Xochimilco. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ "Feria del Maíz y la Tortilla" [Corn and Tortilla Fair] (in Spanish). Xochimilco, Mexico City: Borough of Xochimilco. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ "Feria de la Alegría y el Olivo 2011" [Alegría and Olive Fair] (in Spanish). Xochimilco, Mexico City: Borough of Xochimilco. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ Pantoja, Sara (January 28, 2010). "Celebrarán feria del amaranto en Xochimilco" [Celebrating the amaranth fair]. El Universal (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ "Feria Nacional del Dulce Cristalizado 2010" [National Fair of Crystallized Candies 2010] (in Spanish). Xochimilco, Mexico City: Borough of Xochimilco. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ "Carnaval Xochimilco (antes Carnaval Cultural Vive Xochimilco)" [Xochimilco Carnival (before Cultural Carnival Vive Xochimilco)]. Festivales México (in Spanish). Mexico: CONACULTA. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ "Sin Azul (2002) – IMDb" – via m.imdb.com.

- ^ "Mercado de Plantas Cuemanco" [The Cuemanco Plant Market] (in Spanish). Xochimilco, Mexico City: Borough of Xochimilco. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Jiménez González, p55.

- ^ Valdez, Ilich (December 15, 2007). "Domina Xochimilco en flor de nochebuena" [Xochimilco dominates pointsettias]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 2.

- ^ Notimex (February 7, 2011). "Denuncian prestadores de servicio turístico de Xochimilco competencia desleal" [Tourist services providers denounce unfair competition]. Radio Forumula (in Spanish). Mexico City. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ Farías Galindo, José. "Museo Arqueológico de Xochimilco" [The Archeological Museum of Xochimilco] (in Spanish). Xochimilco, Mexico City: Borough of Xochimilco. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ a b Jiménez González, p 56.

- ^ a b Jiménez González, p 58.

- ^ "Michimani:lugar de pescadores" [Michmani: Place of Fishermen] (in Spanish). Xochimilco, Mexico City: Borough of Xochimilco. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ "Origen de la UAM Xochimilco" [Origen of UAM Xochimilco] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Universidad Autónoma Metropólitana. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ Rodríguez, Judith (2008). "225 años de La Academia de San Carlos" [225 year of the San Carlos Academy]. Artes e Historia (in Spanish). Mexico: CONACULTA. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ Salazar Arroyo, Ignacio (May 2006). "Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas" [National School of Fine Arts] (PDF) (in Spanish). Mexico City: Radio UNAM. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 22, 2011. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ "Concursos Interpreparatorianos CONVOCATORIA OFICIAL 2013–2014" (Archived 2015-09-29 at the Wayback Machine). National Autonomous University of Mexico Senior High Schools. Retrieved on June 27, 2014. p. 10/53. "La final interpreparatoriana tendrá lugar el viernes 7 de marzo de 2014, a las 11:00 horas, en el las instalaciones del plantel 1 “Gabino Barreda”, ubicado en Avenida las Torres esquina con Aldama s/n, Colonia Tepepan, Delegación Xochimilco."

- ^ "Planteles Xochimilco." Instituto de Educación Media Superior del Distrito Federal. Retrieved on May 28, 2014.

- ^ "Ubicaciones"/"Standorte Archived 2016-04-27 at the Wayback Machine." Colegio Alemán Alexander von Humboldt. Retrieved on April 4, 2016. "PLANTEL TEPEPAN Kindergarten – Primaria Camino Real a Xochitepec 89 Col. Tepepan, Del. Xochimilco 16030 México, D.F." and "PLANTEL LA NORIA Av. México 5501 Col. Huichapan (La Noria), Del. Xochimilco 16030 México D.F." and " PLANTEL PEDREGAL Kindergarten Camino a Santa Teresa 1579 Jardines del Pedregal, Álvaro Obregón 01900 Ciudad de México, Distrito Federal, México"

References

[edit]- Cline, S.L., "A Cacicazgo in the Seventeenth Century: The Case of Xochimilco." in Land and Politics in Mexico, Ed. H.R. Harvey.|University of New Mexico Press1991, pp. 265–274

- Jiménez González, Victor Manuel (2009). Ciudad de México: Guía para descubrir los encantos de la Ciudad de México [Mexico City: Guide to discover the charms of Mexico City] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Editorial Océano, S.L. ISBN 978-607-400-061-0.

- National Research Council Staff (1995). Mexico City's Water Supply : Improving the Outlook for Sustainability. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-05245-0.

External links

[edit]- (in Spanish) Alcaldía de Xochimilco website

- (in English) Environmentalgraffiti.com blog: "The Island of Dolls" — article and photographs.

- (in Spanish and English) Soy Xochimilco – CONABIO via YouTube