Languages of Africa: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

There are an estimated 2000 languages spoken in [[Africa]].<ref>[http://www.panafril10n.org/wikidoc/pmwiki.php/PanAfrLoc/MajorLanguages Major Languages of Africa]</ref> |

There are an estimated 2000 languages spoken in [[Africa]].<ref>[http://www.panafril10n.org/wikidoc/pmwiki.php/PanAfrLoc/MajorLanguages Major Languages of Africa]</ref> |

||

African languages such as [[Swahili language|Swahili]], [[Hausa language|Hausa]], Igbo, and [[Yoruba language|Yoruba]], Ibibio language of the Ibibio/Annang/Efik people [Ibibio], [Annang] and [Efik] are spoken by millions of people. Others, such as [[Laal language|Laal]], [[Shabo language|Shabo]], and [[Dahalo language|Dahalo]], are spoken by a few hundred or fewer. In addition, Africa has a wide variety of [[sign language]]s, many of whose genetic classification has yet to be worked out. Several African languages are also [[whistled language|whistled]] for special purposes. |

African languages such as [[Swahili language|Swahili]], [[Hausa language|Hausa]], Igbo, and [[Yoruba language|Yoruba]], Ibibio language of the Ibibio/Annang/Efik people [[Ibibio]], [[Annang]] and [[Efik]] are spoken by millions of people. Others, such as [[Laal language|Laal]], [[Shabo language|Shabo]], and [[Dahalo language|Dahalo]], are spoken by a few hundred or fewer. In addition, Africa has a wide variety of [[sign language]]s, many of whose genetic classification has yet to be worked out. Several African languages are also [[whistled language|whistled]] for special purposes. |

||

The abundant linguistic diversity of many African countries has made [[language policy]] an extremely important issue in the neo-colonial era. In recent years, African countries have become increasingly aware of the value of their linguistic inheritance. Language policies that are being developed nowadays are mostly aimed at [[multilingualism]]. For example, all African languages are considered [[languages of the African Union|official languages of the African Union]] (AU). 2006 was declared by AU as the "Year of African Languages".<ref>[http://www.sarpn.org.za/documents/d0001850/index.php African Union Summit 2006] |

The abundant linguistic diversity of many African countries has made [[language policy]] an extremely important issue in the neo-colonial era. In recent years, African countries have become increasingly aware of the value of their linguistic inheritance. Language policies that are being developed nowadays are mostly aimed at [[multilingualism]]. For example, all African languages are considered [[languages of the African Union|official languages of the African Union]] (AU). 2006 was declared by AU as the "Year of African Languages".<ref>[http://www.sarpn.org.za/documents/d0001850/index.php African Union Summit 2006] |

||

Revision as of 20:28, 22 October 2007

The Languages of Africa are a diverse set of languages, many of which bear little relation to one another. European language has a great deal of influence due to the recent history of colonization.

There are an estimated 2000 languages spoken in Africa.[1] African languages such as Swahili, Hausa, Igbo, and Yoruba, Ibibio language of the Ibibio/Annang/Efik people Ibibio, Annang and Efik are spoken by millions of people. Others, such as Laal, Shabo, and Dahalo, are spoken by a few hundred or fewer. In addition, Africa has a wide variety of sign languages, many of whose genetic classification has yet to be worked out. Several African languages are also whistled for special purposes.

The abundant linguistic diversity of many African countries has made language policy an extremely important issue in the neo-colonial era. In recent years, African countries have become increasingly aware of the value of their linguistic inheritance. Language policies that are being developed nowadays are mostly aimed at multilingualism. For example, all African languages are considered official languages of the African Union (AU). 2006 was declared by AU as the "Year of African Languages".[2]

Language Families

Most African languages belong to one of four language families: Afro-Asiatic, Nilo-Saharan, Niger-Congo, and Khoisan. A handful of languages associated with the continent are Indo-European or Austronesian, however, their presence dates to less than 500 and 1000 years ago, respectively, and their closest linguistic relatives are primarily non-African. In addition, African languages include several unclassified languages, and also sign languages.

Formerly known as Hamito-Semitic languages, Afro-Asiatic languages are spoken in large parts of North Africa, East Africa, and Southwest Asia. The Afro-Asiatic language family comprises approximately 375 languages spoken by 285 million people. The main subfamilies of Afro-Asiatic are the Semitic languages, the Cushitic languages, Berber, and the Chadic languages. The Semitic languages are the only branch of Afro-Asiatic located outside of Africa.

Some of the most widely spoken Afro-Asiatic languages include Arabic (Semitic), Amharic (Semitic), Oromo (Cushitic), and Hausa (Chadic). Of all the world's surviving language families, Afro-Asiatic has the longest written history, since both Ancient Egyptian and Akkadian are members.

The Nilo-Saharan languages includes an array of diverse languages, a categorisation that is not entirely agreed upon. They mainly include languages spoken in Sudan, Ethiopia, Uganda, Kenya, and northern Tanzania. Some languages in Central and West African are also classified as Nilo-Saharan. The family consists of more than a hundred languages. Nilo-Saharan languages are often sub-divided into Komuz languages, Saharan languages (including Kanuri language, Songhay languages, Fur languages (including Fur language), Maban languages, Central Sudanic languages, Kunama language, Berta language, Eastern Sudanic languages.

Eastern Sudanic languages are subdivided into Nubian languages and Nilotic languages. Nilotic languages include Eastern Nilotic languages, Southern Nilotic languages and Western Nilotic languages

Nilo-Saharan languages include an array of languages, including Luo languages in Sudan, Uganda,Kenya and Tanzania (eg. Acholi, Lango, Dholuo), Ateker in Uganda and Kenya (eg. Teso, Karamojong and Turkana), Maasai (Kenya and Tanzania), Kalenjin (Kenya), Kanuri (Nigeria, Niger, Chad) and Songhay (Mali, Niger). Most Nilo-Saharan languages are tonal.

The Kadu languages were formerly grouped with the Kordofanian languages, but are nowadays often considered part of the Nilo-Saharan family. The Nilotic languages, having expanded substantially with the Nilotic peoples in recent centuries, are a geographically widespread language family and have a large population.

The Niger-Congo language family is the largest group of Africa (and probably of the world) in terms of different languages. One of its salient features, still shared by most of the Niger-Congo languages, is the noun class system. The vast majority of languages of this family is tonal. The Bantu family comprises a major branch of Niger-Congo, as visualized by the distinction between Niger-Congo A and B (Bantu) on the map above.

The Niger-Kordofanian language family, joining Niger-Congo with the Kordofanian languages of south-central Sudan, was proposed in 1950s by Joseph Greenberg. It is common today for linguists to use "Niger-Congo" to refer to this entire family, including Kordofanian as a subfamily. One reason for this is that it is not clear whether Kordofanian was the first branch to diverge from rest of Niger-Congo. Mandé has been claimed to be equally or more divergent.

Niger-Congo is generally accepted by linguists, though a few question the inclusion of Kordofanian or Mandé.

The Khoi-San languages number about 50, and are spoken by about 120,000 people. They are found mainly in Namibia, Botswana, and Angola. Two distant languages usually considered Khoi-San are Sandawe and Hadza of Tanzania. Many linguists regard the Khoi-San phylum as a yet unproven hypothesis.

A striking — and nearly unique — characteristic of the Khoi-San languages is their use of click consonants. Some neighbouring Bantu languages (notably Xhosa and Zulu) have adopted some click sounds from the Khoi-San languages, as has the Cushitic language Dahalo; but only a single language, the Australian ritual language Damin, is reported to use clicks without being a result of Khoi-San influence. All of the Khoi-San languages are tonal.

Non-African families

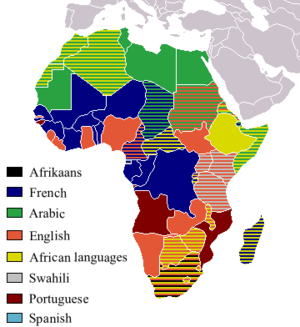

The above are families indigenous to Africa. Several African languages belong to non-African families: Malagasy, the most common language of Madagascar, is an Austronesian language, and Afrikaans is Indo-European, as is the lexifier of most African creoles. Since the colonial era, European languages like Portuguese, English and French (African French) are also found on the African continent (all are official languages), as are Indian languages such as Gujarati. Other Indo-European languages have also been heard in various parts of the continent in earlier historical times, such as Old Persian and Greek (in Egypt), Latin (in North Africa), and Modern Persian (in settlements along the Indian Ocean).

Creole languages

Due partly to its multilingualism and its colonial past, a substantial proportion of the world's creole languages are to be found in Africa. Some are based on European languages (eg Krio from English in Sierra Leone and the very similar Pidgin in Cameroon and Nigeria, Cape Verdean Creole in Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau Creole in Guinea-Bissau and Senegal both from Portuguese, Seychellois Creole from French in the Seychelles, or Mauritian Creole in Mauritius); some are based on Arabic (e.g., Juba Arabic in the southern Sudan, or Nubi in parts of Uganda and Kenya); some are based on local languages (e.g., Sango, the main language of the Central African Republic.)

Unclassified languages

A fair number of unclassified languages are reported in Africa; many remain unclassified simply for lack of data, but among the better-investigated ones may be listed:

Less well investigated ones include Bete, Bung, Kujarge, Lufu, Mpre, Oropom, and Weyto. Several of these are extinct, and adequate comparative data is thus unlikely to be forthcoming.

In addition, the placement of Kadu, Kordofanian, Hadza, and Sandawe - among others - is controversial, as discussed above.

Sign languages

Many African countries have national sign languages - such as Algerian Sign Language, Tunisian Sign Language, Ethiopian Sign Language - while other sign languages are restricted to small areas or single villages, such as Adamorobe Sign Language in Ghana. Little has been published on most of these languages since not much is known.

Language in Africa

Throughout the long multilingual history of the African continent, African languages have been subject to phenomena like language contact, language expansion, language shift, and language death. A case in point is the Bantu expansion, the process of Bantu-speaking peoples expanding over most of the Sub-Saharan part of Africa, thereby displacing Khoi-San speaking peoples in much of East-Africa. Another example is the Islamic expansion in the 7th century AD, marking the start of a period of profound Arabic influence in North Africa.

With so many totally unrelated families represented over wide areas, the image of the African linguistic situation is that of a veritable "Babel", although it is true that a certain number of languages categorized as distinct are in fact mutually intelligible dialects to some degree - eg. the Nguni languages of Southern Africa or the Manding languages of West Africa.

Trade languages are another age-old phenomenon in the African linguistic landscape. Cultural and linguistic innovations spread along trade routes and languages of peoples dominant in trade developed into languages of wider communication (linguae francae). Of particular importance in this respect are Jula (western West Africa), Fulfulde (West Africa, mainly across the Sahel), Hausa (eastern West Africa), Lingala (Congo), Swahili (East Africa) and Arabic (North Africa and into the Sahel).

After gaining independence, many African countries, in the search for national unity, selected one language (generally the former colonial language) to be used in government and education. In recent years, African countries have become increasingly aware of the importance of linguistic diversity. Language policies that are being developed nowadays are mostly aimed at multilingualism.

Cross-border languages

The colonial borders established by European powers following the Berlin Conference in 1884-5 divided a great many ethnicities and African language speaking communities. In a sense, then, "cross-border languages" is a misnomer. Nevertheless it describes the reality of many African languages, which has implications for divergence of language on either side of a border (especially when the official languages are different), standards for writing the language, etc.

Some prominent Africans such as former Malian president and current Chairman of the African Commission, Alpha Oumar Konaré, have referred to cross-border languages as a factor that can promote African unity.[3]

Language change & planning

Language is not static in Africa any more than in other world regions. In addition to the (probably modest) impact of borders, there are also cases of dialect levelling (such as in Igbo and probably many others), koines (such as N'Ko and possibly Runyakitara), and emergence of new dialects (such as Sheng). In some countries there are official efforts to develop standardized language versions.

There are also many less-widely spoken languages that may be considered endangered languages.

Demographics

Of the 890 million Africans (as of 2005), about 20% speak an Arabic dialect (the vast majority of North Africans). About 10% speak Swahili, the lingua franca of Southeastern Africa, and about 5% speak Hausa, a West African lingua franca. Other important West African languages are Yoruba (3%) and Fula (2%). Major East African languages are Oromo (4%) and Somali (2%), important South African languages Zulu and Afrikaans.

List of major African languages (by total number of speakers)

| Swahili (Southeast Africa) | 5-10 million native + 80 secondary |

| Maghrebi Arabic | 80 |

| Egyptian Arabic | 76 |

| Hausa (West Africa) | 24 native + 15 secondary |

| Oromo (East Africa) | 30-35 |

| Yoruba (West Africa) | 25 |

| Sudanese Arabic | 19 |

| Somali (Somalia) | 15 |

| Igbo (Nigeria) | 10-16 |

| Fula (West Africa) | 10-16 |

| Malagasy (Madacascar) | 17 |

| Zulu (South Africa) | 10 |

| Afrikaans (South Africa) | 10 |

| Chichewa (East Africa) | 9 |

| Akan | 9 |

| Shona | 7 |

| Xhosa (South Africa) | 8 |

| Kinyarwanda (Rwanda) | 7 |

| Kongo | 7 |

| Tigrinya | 7 |

| Tshiluba (Congo) | 6 |

| Wolof | 3 native + 3 secondary |

| Gikuyu (Kenya) | 5 |

| More (West Africa) | 5 |

| Kirundi (Central Africa) | 5 |

| Sotho (South Africa) | 5 |

| Luhya | 4 |

| Tswana (Southern Africa) | 4 |

| Kanuri (West Africa) | 4 |

| Umbundu (Angola) | 4 |

| Northern Sotho (South Africa) | 4 |

Linguistic features

The one thing African languages have in common is the fact that they are spoken in Africa. Africa does not represent some sort of natural linguistic area. Nevertheless, some linguistic features are cross-linguistically particularly common to languages spoken in Africa, whereas other features seem to be more uncommon. The hypothesis that shared traits like this would point to a common origin of all African languages is highly dubious. Language contact (resulting in borrowing) and, with regard to specific idioms and phrases, a similar cultural background have been put forward to account for some of the similarities.

Among common pan-African linguistic features are the following (Greenberg 1983): certain phoneme types, such as implosives; doubly articulated labial-velar stops like /kp/ and /gb/; prenasalised consonants; clicks; and the lower high (or 'near close') vowels /ʊ/ and /ɪ/. Phoneme types that are relatively uncommon in African languages include uvular consonants, diphthongs, and front rounded vowels. Quite frequently, only one term is used for both animal and meat; additionally, the word nama or nyama for animal/meat is particularly widespread in otherwise widely divergent African languages. Widespread syntactical structures include the common use of adjectival verbs and the expression of comparison by means of a verb to surpass.

Tonal languages are found throughout the world; in Africa, they are especially numerous. Both the Nilo-Saharan and the Khoi-San phyla are fully tonal. The large majority of the Niger-Congo languages is also tonal. Tonal languages are furthermore found in the Omotic, Chadic, and South & East Cushitic branches of Afro-Asiatic. The most common type of tonal system opposes two tone levels, High (H) and Low (L). Contour tones do occur, and can often be analysed as two or more tones in succession on a single syllable. Tone melodies play an important role, meaning that it is often possible to state significant generalizations by separating tone sequences ('melodies') from the segments that bear them. Tonal sandhi processes like tone spread, tone shift, and downstep and downdrift are common in African languages.

See also

- Polyglotta Africana

- The Languages of Africa

- Joseph Greenberg

- Diedrich Hermann Westermann

- Malcolm Guthrie

- Wilhelm Bleek

- Karl Lepsius

- Carl Meinhof

- Languages of the African Union

- Writing systems of Africa

- List of African languages

References

African languages

- Childs, G. Tucker (2003) An Introduction to African Languages. Amsterdam: John Benjamin.

- Elugbe, Ben (1998) "Cross-border and Major Languages of Africa." In K. Legère, ed. Cross-border languages : reports and studies, Regional Workshop on Cross-Border Languages, National Institute for Educational Development (NIED), Okahandja, 23-27 September 1996. Windhoek: Gamsberg Macmillan

- Heine, Bernd & Derek Nurse (eds.) (2000) African languages: an introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Webb, Vic and Kembo-Sure (eds.) (1998) African Voices. An introduction to the languages and linguistics of Africa. Cape Town: Oxford University Press Southern Africa.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. (1983) 'Some areal characteristics of African languages', in Dihoff, Ivan R. (ed.) Current Approaches to African Linguistics (vol. 1) (Publications in African Languages and Linguistics vol. 1). Dordrecht: Foris, 3-21.

- Wedekind, Klaus (1985) 'Thoughts when drawing a map of tone languages' Afrikanistische Arbeitspapiere 1, 105-24.

- Ellis, Stephen (ed.) (1996) Africa Now. People – Policies – Institutions. The Hague: Ministry of Foreign Affairs (DGIS).

- Chimhundu, Herbert (2002) Language Policies in Africa. (Final report of the Intergovernmental conference on language policies in Africa) Revised version. UNESCO.

- Cust, Robert Needham (1883) Modern Languages of Africa.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. (1966) The Languages of Africa (2nd ed. with additions and corrections). [Originally published as International journal of American linguistics, 29, 1, part 2 (1963)]. Bloomington: Indiana University.

- Westermann, Diedrich H. (1952). The languages of West Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ethnologue.com's Africa: A listing of African languages and language families.

Notes

- ^ Major Languages of Africa

- ^ African Union Summit 2006 Khartoum, Sudan. SARPN

- ^ African languages for Africa's development ACALAN (French & English)

External links