Broadway theatre: Difference between revisions

→Runs: +ref and info |

|||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

===Runs=== |

===Runs=== |

||

Most Broadway shows are commercial productions intended to make a profit for the producers and investors (''"backers"''), and therefore meant to have open-ended runs, meaning that they may be presented for a varying number of weeks depending on critical response, word of mouth, and the effectiveness of the show's advertising, all of which determine ticket sales. However, some Broadway shows are produced by non-commercial organizations as part of a regular subscription season — [[Lincoln Center|Lincoln Center Theater]], [[Roundabout Theatre Company]], [[Playwrights Horizons]] and [[Manhattan Theatre Club]] are the four non-profit theatre companies that currently have permanent Broadway venues. Some other productions |

Most Broadway shows are commercial productions intended to make a profit for the producers and investors (''"backers"''), and therefore meant to have open-ended runs, meaning that they may be presented for a varying number of weeks depending on critical response, word of mouth, and the effectiveness of the show's advertising, all of which determine ticket sales. However, some Broadway shows are produced by non-commercial organizations as part of a regular subscription season — [[Lincoln Center|Lincoln Center Theater]], [[Roundabout Theatre Company]], [[Playwrights Horizons]] and [[Manhattan Theatre Club]] are the four non-profit theatre companies that currently have permanent Broadway venues. Some other productions are produced on Broadway with "limited engagement runs" for a number of reasons, including financial issues, prior engagements of the performers, temporary availability of a theatre between the exit of one production and the entrance of another scheduled production. However, some shows begin with limited engagement runs and, like 2007's [[August: Osage County]], after critical acclaim or box office success, they extend their engagements to open-ended runs. |

||

Musicals on Broadway tend to have |

Musicals on Broadway tend to have longer runs than do ''"straight"'' (i.e. non-musical) plays. On [[January 9]], [[2006]], ''[[The Phantom of the Opera (1986 musical)|The Phantom of the Opera]]'' at the [[Majestic Theatre]] became the longest running Broadway musical, with 7,486 performances, overtaking ''[[Cats (musical)|Cats]]''.<ref>[http://www.playbill.com/celebritybuzz/article/75222.html List of longest runs on Broadway]</ref> |

||

===Touring=== |

===Touring=== |

||

Revision as of 04:50, 19 February 2008

Broadway theatre,[1] or a Broadway show, refers to a performance, usually of a play or musical, presented in one of the 39 large professional theatres with 500 seats or more located in the Theatre District of the New York City borough of Manhattan.[2] [3] Broadway theatre is the best known form of professional theatre to the general public in the United States and the most lucrative for the performers, technicians and others involved in putting on the shows. Along with London's West End theatre, Broadway theatre is usually considered to represent the highest level of commercial theatre in the English-speaking world.

The shows that reach Broadway and thrive there have historically been perceived as generally mainstream and less likely to be cutting edge than some produced Off- and Off-Off-Broadway or in regional non-profit theatres.

The Broadway theatre district is a key tourist attraction in New York City. According to the The Broadway League, Broadway shows sell over one and a half billion dollars worth of tickets annually.

History

18th and 19th centuries

New York (and so, America) did not have a significant theatre presence until about 1750, when actor-managers Walter Murray and Thomas Kean established a resident theatre company at the Theatre on Nassau Street, which held about 280 people. They presented Shakespeare plays and ballad operas such as The Beggar’s Opera.[4] In 1752, William Hallam sent a company of twelve actors from Britain to the colonies with his brother Lewis as their manager. They established a theatre in Williamsburg, Virginia and opened with The Merchant of Venice and The Anatomist. The company moved to New York in the summer of 1753, performing ballad operas and ballad-farces like Damon and Phillida. The Revolutionary War suspended theatre in New York, but thereafter theatre resumed, and in 1798, the 2,000-seat Park Theatre was built on Chatham Street (now called Park Row).[4] The Bowery Theatre opened in 1826, followed by others. Blackface minstrel shows, a distinctly American form of entertainment, became popular in the 1830s, and especially so with the arrival of the Virginia Minstrels in the 1840s.

By the 1840s, P.T. Barnum was operating an entertainment complex in lower Manhattan. In 1829, at Broadway and Prince Street, Niblo's Garden opened and soon became one of New York's premiere night spots. The 3,000-seat theatre presented all sorts of musical and non-musical entertainments. The Astor Place Theatre opened in 1847. A riot broke out in 1849 when the lower-class patrons of the Bowery objected to what they perceived as snobbery by the upper class audiences at Astor Place:

- "After the Astor Place Riot of 1849 entertainment in New York City was divided along class lines: opera was chiefly for the upper middle and upper classes, minstrel shows and melodramas for the middle class, variety shows in concert saloons for men of the working class and the slumming middle class.[5]

Theatre in New York moved from downtown gradually to midtown beginning around 1850, seeking less expensive real estate prices. In 1870, the heart of Broadway was in Union Square, and by the end of the century, many theatres were near Madison Square. Theatres did not arrive in the Times Square area until the early 1900s, and the Broadway theatres did not consolidate there until a large number of theatres were built around the square in the 1920s and 1930s. Broadway's first "long-run" musical was a 50 performance hit called The Elves in 1857. New York runs continued to lag far behind those in London,[6] but Laura Keene's "musical burletta" Seven Sisters (1860) shattered previous New York records with a run of 253 performances. It was at a performance by Keene's troupe of Our American Cousin in Washington, D.C. that Abraham Lincoln was shot.

The first theatre piece that conforms to the modern conception of a musical, adding dance and original music that helped to tell the story, is generally considered to be The Black Crook, which premiered in New York on September 12 1866. The production was a staggering five-and-a-half hours long, but despite its length, it ran for a record-breaking 474 performances. The same year, The Black Domino/Between You, Me and the Post was the first show to call itself a "musical comedy."[7]

Tony Pastor opened the first vaudeville theatre one block east of Union Square in 1881, where Lillian Russell performed. Comedians Edward Harrigan and Tony Hart produced and starred in musicals on Broadway between 1878 (The Mulligan Guard Picnic) and 1885, with book and lyrics by Harrigan and music by his father-in-law David Braham. These musical comedies featured characters and situations taken from the everyday life of New York's lower classes and represented a significant step forward from vaudeville and burlesque, towards a more literate form. They starred high quality singers (Lillian Russell, Vivienne Segal, and Fay Templeton) instead of the ladies of questionable repute who had starred in earlier musical forms.

As transportation improved, poverty in New York diminished, and street lighting made for safer travel at night, the number of potential patrons for the growing number of theatres increased enormously. Plays could run longer and still draw in the audiences, leading to better profits and improved production values. As in England, during the latter half of the century the theatre began to be cleaned up, with less prostitution hindering the attendance of the theatre by women. Gilbert and Sullivan's family-friendly comic opera hits, beginning with H.M.S. Pinafore in 1878, were imported to New York (by the authors and also in numerous pirated productions). They were imitated in New York by American productions such as Reginald DeKoven's Robin Hood (1891) and John Philip Sousa's El Capitan (1896), along with operas, ballets and other British and European hits.

1890s and later

Charles Hoyt's A Trip to Chinatown (1891) became Broadway's long-run champion, holding the stage for 657 performances. This would not be surpassed until Irene in 1919. In 1896, theatre owners Marc Klaw and A. L. Erlanger formed the Theatrical Syndicate, which controlled almost every legitimate theater in the U.S. for the next sixteen years.[8] However, smaller vaudeville and variety houses proliferated, and Off-Broadway was well established by the end of the 19th century.

A Trip to Coontown (1898) was the first musical comedy entirely produced and performed by African Americans in a Broadway theatre (largely inspired by the routines of the minstrel shows), followed by the ragtime-tinged Clorindy the Origin of the Cakewalk (1898), and the highly successful In Dahomey (1902). Hundreds of musical comedies were staged on Broadway in the 1890s and early 1900s comprised of songs written in New York's Tin Pan Alley involving composers such as Gus Edwards, John Walter Bratton, and George M. Cohan (Little Johnny Jones (1904), 45 Minutes From Broadway (1906), and George Washington Jr. (1906)). Still, New York runs continued to be relatively short, with a few exceptions, compared with London runs, until World War I.[9] A few very successful British musicals continued to achieve great success in New York, including Florodora in 1900-01.

In the early years of the 20th century, translations of popular late-19th century continental operettas were joined by the "Princess Theatre" shows of the 1910s by writers such as P. G. Wodehouse, Guy Bolton and Harry B. Smith. Victor Herbert, whose work included some intimate musical plays with modern settings as well as his string of famous operettas (The Fortune Teller (1898), Babes in Toyland (1903), Mlle. Modiste (1905), The Red Mill (1906), and Naughty Marietta (1910)).[10] Beginning with The Red Mill, Broadway shows installed electric signs outside the theatres. Since colored bulbs burned out too quickly, white lights were used, and Broadway was nicknamed "The Great White Way." In August 1919, the Actors Equity Association demanded a standard contract for all professional productions. After a strike shut down all the theatres, the producers were forced to agree. By the 1920s, the Shubert Brothers had risen to take over the majority of the theatres from the Erlanger syndicate.[11]

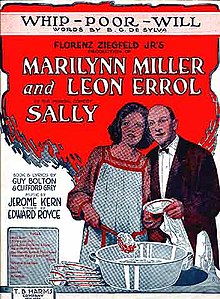

The motion picture mounted a challenge to the stage. At first, films were silent and presented only limited competition. But by the end of the 1920s, films like The Jazz Singer could be presented with synchronized sound, and critics wondered if the cinema would replace live theatre altogether. The musicals of the Roaring Twenties, borrowing from vaudeville, music hall and other light entertainments, tended to ignore plot in favor of emphasizing star actors and actresses, big dance routines, and popular songs. Florenz Ziegfeld produced annual spectacular song-and-dance revues on Broadway featuring extravagant sets and elaborate costumes, but there was little to tie the various numbers together. Typical of the 1920s were lighthearted productions like Sally; Lady Be Good; Sunny; No, No, Nanette; Oh, Kay!; and Funny Face. Their books may have been forgettable, but they produced enduring standards from George Gershwin, Cole Porter, Jerome Kern, Vincent Youmans, and Rodgers and Hart, among others, and Noel Coward, Sigmund Romberg and Rudolf Friml continued in the vein of Victor Herbert. Clearly, the live theatre survived the invention of cinema.

Leaving these comparatively frivolous entertainments behind, and taking the drama a giant step forward, Show Boat, premiered on December 27 1927 at the Ziegfeld Theatre, representing a complete integration of book and score, with dramatic themes, as told through the music, dialogue, setting and movement, woven together more seamlessly than in previous musicals. It ran for a total of 572 performances. After the lean years of the Great Depression, Broadway theatre entered a golden age with the blockbuster hit Oklahoma!, in 1943, which ran for 2,212 performances. Hit after hit followed on Broadway, and the Broadway theatre attained the highest level of international prestige in theatre.

The Tony Awards were established in 1947 to recognize achievement in live American theatre, especially Broadway theatre.

Broadway today

Schedule

Although there are now more exceptions than there once were, generally shows with open-ended runs operate on the same schedule, with evening performances Tuesday through Saturday with an 8 p.m. "curtain" and afternoon "matinée" performances on Wednesday, Saturday and Sunday; typically at 2 p.m. on Wednesdays and Saturdays and 3 p.m. on Sundays, making a standard eight performance week. On this schedule, shows do not play on Monday, and the shows and theatres are said to be "dark" on that day. Actors and crew in these shows tend to regard Sunday evening through Tuesday evening as their "weekend". The Tony Award presentation ceremony is usually held on a Sunday evening in June to fit into this schedule.

In recent years, many shows have moved their Tuesday show time an hour earlier to 7 p.m. The rationale for the move was that fewer tourists took in shows midweek, so the Tuesday crowd in particular depends on local audience members. The earlier curtain therefore allows suburban patrons time after a show to get home by a reasonable hour. Some shows, especially those produced by Disney, change their performance schedules fairly frequently, depending on the season, in order to maximize access to their targeted audience.

Personnel

Both musicals and stage plays on Broadway often rely on casting well-known performers in leading roles to draw larger audiences or bring in new audience members to the theatre. Actors from movies and television are frequently cast for the revivals of Broadway shows or are used to replace actors leaving a cast. There are still, however, performers who are primarily stage actors, spending most of their time "on the boards", and appearing in television and in screen roles only secondarily.

In the past, stage actors had a somewhat superior attitude towards other kinds of live performances, such as vaudeville and burlesque, which were felt to be tawdry, commercial and low-brow — they considered their own craft to be a higher and more artistic calling. This attitude is reflected in the term used to describe their form of stage performance: "legitimate theatre". (The abbreviated form "legit" is still used for live theatre by the entertainment industry newspaper Variety as part of its unique "slanguage.")[12] This rather condescending attitude also carried over to performers who worked in radio, film and television instead of in "the theatre", but this attitude is much less prevalent now, especially since film and television work pay so much better than almost all theatrical acting, even Broadway. The split between "legit" theatre and "variety" performances still exists, however, in the structure of the actors' unions: Actors' Equity represents actors in the legitimate theatre, and the American Guild of Variety Artists (AGVA) represents them in performances without a "book" or through-storyline — although it's very rare for Broadway actors not to work under an Equity contract, since most plays and musicals come under that union's jurisdiction.

Almost all of the people involved with a Broadway show at every level are represented by unions or other protective, professional or trade organization. The actors, dancers, singers, chorus members and stage managers are members of Actors' Equity Association (AEA), musicians are represented by the American Federation of Musicians (AFM), and stagehands, dressers, hairdressers, designers, box office personnel and ushers all belong to various locals of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employes, also known as "the IA" or "IATSE" (pronounced "eye-ot-zee"). Directors and choreographers belong to the Society of Stage Directors and Choreographers (SSD&C), playwrights to the Dramatists Guild, and house managers, company managers and press agents belong to the Association of Theatrical Press Agents and Managers (ATPAM). Casting directors (who tried in 2002-2004 to become part of ATPAM) is the last major components of Broadway's human infrastructure who are not unionized. (General managers, who run the business affairs of a show, and are frequently producers as well, are management and not labor.)

Producers and theatre owners

Most Broadway producers and theatre owners are members of the League of American Theatres and Producers, now re-named "The Broadway League", a trade organization that promotes Broadway theatre as a whole, negotiates contracts with the various theatrical unions and agreements with the guilds, and co-administers the Tony Awards with the American Theatre Wing, a service organization. While the League and the theatrical unions are sometimes at loggerheads during those periods when new contracts are being negotiated, they also cooperate on many projects and events designed to promote professional theatre in New York.

The three non-profit theatre companies with Broadway theatres ("houses") belong to the League of Resident Theatres and have contracts with the theatrical unions which are negotiated separately from the other Broadway theatre and producers. (Disney also negotiates apart from the League, as did Livent before it closed down its operations.) However, generally, shows that play in any of the Broadway houses are eligibile for Tony Awards (see below).

The majority of Broadway theatres are owned or managed by three organizations: the Shubert Organization, a for-profit arm of the non-profit Shubert Foundation, which owns 17 theatres (it recently retained full ownership of the Music Box from the Irving Berlin Estate); The Nederlander Organization, which controls 9 theatres; and Jujamcyn, which owns five Broadway houses.

Runs

Most Broadway shows are commercial productions intended to make a profit for the producers and investors ("backers"), and therefore meant to have open-ended runs, meaning that they may be presented for a varying number of weeks depending on critical response, word of mouth, and the effectiveness of the show's advertising, all of which determine ticket sales. However, some Broadway shows are produced by non-commercial organizations as part of a regular subscription season — Lincoln Center Theater, Roundabout Theatre Company, Playwrights Horizons and Manhattan Theatre Club are the four non-profit theatre companies that currently have permanent Broadway venues. Some other productions are produced on Broadway with "limited engagement runs" for a number of reasons, including financial issues, prior engagements of the performers, temporary availability of a theatre between the exit of one production and the entrance of another scheduled production. However, some shows begin with limited engagement runs and, like 2007's August: Osage County, after critical acclaim or box office success, they extend their engagements to open-ended runs.

Musicals on Broadway tend to have longer runs than do "straight" (i.e. non-musical) plays. On January 9, 2006, The Phantom of the Opera at the Majestic Theatre became the longest running Broadway musical, with 7,486 performances, overtaking Cats.[13]

Touring

In addition to long runs in Broadway theatres, producers often remount their productions with a new cast and crew for the Broadway national tour, which travels to theatres in major cities across the country — the bigger and more successful shows may have several of these touring companies out at a time, some of them "sitting down" in other cities for their own long runs. Smaller cities are eventually serviced by "bus & truck" tours, so-called because the cast generally travels by bus (instead of by air) and the sets and equipment by truck. Tours of this type, which frequently feature a reduced physical production to accommodate smaller venues and tighter schedules, often play "split weeks" (half a week in one town and the second half in another) or "one-nighters", whereas the larger tours will generally play for one or two weeks per city at a minimum. The Touring Broadway Awards, presented by The League of American Theatres and Producers, honor excellence in touring Broadway.

Audience

Seeing a Broadway show is a common tourist activity in New York, and Broadway theatre generates billions of dollars annually. The TKTS booths — one in Duffy Square (47th Street between Broadway and 7th Avenue) and one in Lower Manhattan (199 Water Street — Corner of Front & John Streets) — sell same-day tickets for many Broadway and Off-Broadway shows at a discount ranging from 10% to 50%. This service helps sell seats that would otherwise go empty, and makes seeing a show in New York more affordable. Many Broadway theatres also offer special student rates, same-day "rush" tickets, or standing-room tickets to help ensure that their theatres are as full, and their "grosses" as high, as possible.

Some theatregoers prefer the more experimental, challenging, and intimate performances possible in smaller theatres, which are referred to as Off-Broadway and Off-Off-Broadway (though some may be physically located on or near Broadway). An example of this would be the hit musical Spring Awakening, which began its run Off-Broadway in a small, intimate environment, and continued onto Broadway, where it still gives the similar, intimate experience. The classification of theatres is governed by language in Actors' Equity Association contracts. To be eligible for a Tony, a production must be in a house with 500 seats or more and in the Theatre District, which criteria defines Broadway theatre.

Total Broadway attendance in the 2006-2007 season was just over 12 million.[14] This was approximately the same as London's West End theatre (which reported total attendance of 12.357 for major commercial and grant-aided theatres in Central London for 2006).[15] Attendance rose slightly from the previous season (2005-2006), when attendance first reached the 12 million mark.

Tony Awards

Broadway shows and artists are honored every June when the Antoinette Perry Awards (Tony Awards) are given by the American Theatre Wing and the League of American Theatres and Producers. The Tony is Broadway's most prestigious award, the importance of which has increased since the annual broadcast on television began. Celebrities are often chosen to host the show, like Hugh Jackman and Rosie O'Donnell, in addition to celebrity presenters. While some critics have felt that the show should focus on celebrating the stage, many others recognize the positive impact that famous faces lend to selling more tickets and bringing more people to the theatre. The performances from Broadway musicals on the telecast have also been cited as vital to the survival of many Broadway shows. Many theatre people, notably critic Frank Rich, dismiss the Tony awards as little more than a commercial for the limited world of Broadway, which after all can only support a maximum of two dozen shows a season, and constantly call for the awards to embrace off-Broadway theatre as well. (Other awards given to New York theatrical productions, such as the Drama Desk Award and the Outer Circle Critics Award, are not limited to Broadway productions, and honor shows that are presented throughout the city.)

List of Broadway theatres

- If no show is currently running, the play listed is the next show planned (dates marked with an *).

- If the next show planned is not announced, the applicable columns are left blank.

Notes and references

- ^ Although theater is the preferred spelling in the U.S. (see further at American and British English Spelling Differences), the majority of venues, performers, and trade groups for live dramatic presentations use the spelling theatre.

- ^ New York Tourism Department. "New Your Tourism Website". Retrieved 2007-12-18.

- ^ playbill.com article, Feb. 7, 2008, "ASK PLAYBILL.COM: Broadway or Off-Broadway—Part I", retrieved Feb. 8, 2008

- ^ a b John Kenrick article on the history of NY theatre

- ^ Snyder, Robert W. in The Encyclopedia of New York City (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995), Kenneth T. Jackson, editor, p. 1226.

- ^ Article on long runs in New York and London prior to 1920

- ^ a b Sheridan, Morley. Spread A Little Happiness, New York: Thames and Hudson, 1987, p.15

- ^ Kenrick's summary of New York theatre from 1865-1900

- ^ Article on long-running musicals before 1920

- ^ Midkoff, Neil article

- ^ Kenrick's summary of the 20th century history of theatre in New York

- ^ Variety Magazine. "Variety Slanguage Dictionary". Retrieved 2007-12-18.

- ^ List of longest runs on Broadway

- ^ The Broadway League. ""Broadway Season Statistics"". Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ^ Society of London Theatre

External links

- General

- Awards and service organizations

- Unions

- Actors' Equity Association

- The Dramatists Guild of America

- Society of Stage Directors and Choreographers

- American Federation of Musicians

- IATSE

- News, information and ticket sources