Colonial forces of Australia: Difference between revisions

→Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) (1803): tweak wording |

+ image |

||

| Line 54: | Line 54: | ||

The New South Wales Sudan contingent arrived at [[Suakin]] on the [[Red Sea]] on 29 March 1885.<ref name=Kuring16>{{harvnb|Kuring|2004|p=16}}.</ref> There they joined Lieutenant General [[Gerald Graham]]'s two British [[brigade]]'s efforts against [[Osman Digna]]. Within a month of arriving, the New South Wales detachment had seen action at [[Battle of Tamai|Tamai]],<ref>{{harvnb|Coulthard-Clark|1998|pp=52–53}}.</ref> becoming the first Australian raised military force to do so. By May 1885, the [[Mahdist War|campaign]] had been reduced to a series of small skirmishes, the most significant of which for the New South Wales contingent came at [[Battle of Takdul|Takdul]] on 6 May.<ref>{{harvnb|Coulthard-Clark|1998|p=53}}.</ref> They subsequently returned to Sydney by 23 June 1885.<ref name=Grey49/> Despite their service, and their engagements at Tamai and Takdul, the New South Wales Sudan contingent was ridiculed by the media upon their return to New South Wales, as having done nothing to aid the war effort. Many cartoons appeared parodying the force as lazy, or as tourists.{{Citation needed|date=January 2012}} Nevertheless, the contingent's efforts were recognised with an official [[battle honour]] – "Suakin 1885" – which was the first battle honour awarded to an Australian unit.<ref name=Kuring16/> |

The New South Wales Sudan contingent arrived at [[Suakin]] on the [[Red Sea]] on 29 March 1885.<ref name=Kuring16>{{harvnb|Kuring|2004|p=16}}.</ref> There they joined Lieutenant General [[Gerald Graham]]'s two British [[brigade]]'s efforts against [[Osman Digna]]. Within a month of arriving, the New South Wales detachment had seen action at [[Battle of Tamai|Tamai]],<ref>{{harvnb|Coulthard-Clark|1998|pp=52–53}}.</ref> becoming the first Australian raised military force to do so. By May 1885, the [[Mahdist War|campaign]] had been reduced to a series of small skirmishes, the most significant of which for the New South Wales contingent came at [[Battle of Takdul|Takdul]] on 6 May.<ref>{{harvnb|Coulthard-Clark|1998|p=53}}.</ref> They subsequently returned to Sydney by 23 June 1885.<ref name=Grey49/> Despite their service, and their engagements at Tamai and Takdul, the New South Wales Sudan contingent was ridiculed by the media upon their return to New South Wales, as having done nothing to aid the war effort. Many cartoons appeared parodying the force as lazy, or as tourists.{{Citation needed|date=January 2012}} Nevertheless, the contingent's efforts were recognised with an official [[battle honour]] – "Suakin 1885" – which was the first battle honour awarded to an Australian unit.<ref name=Kuring16/> |

||

[[File:A04508 New South Wales Mounted Rifles 1900.jpg|right|thumb|A trooper of the New South Wales Mounted Rifles, c. 1900]] |

|||

In 1885 it was decided to raise a volunteer corps of [[cavalry]] who were to also be partially paid, and had uniforms and weapons supplied, although they had to provide their own horse and equipment. They were eventually formed as a [[Australian Light Horse|light horse]] unit and were known as the [[1st/15th Royal New South Wales Lancers|New South Wales Lancers]]. Many of the previous [[mounted infantry|mounted rifles]] were merged with the Lancers. A further four batteries of reserve artillery were raised in 1885, but disbanded in 1892. The permanent forces added units of [[submarine miners]] and [[mounted infantry]], which were also soon disbanded. The 1890s saw much restructuring, with many units formed and disbanded soon after, or merged with other units. |

In 1885 it was decided to raise a volunteer corps of [[cavalry]] who were to also be partially paid, and had uniforms and weapons supplied, although they had to provide their own horse and equipment. They were eventually formed as a [[Australian Light Horse|light horse]] unit and were known as the [[1st/15th Royal New South Wales Lancers|New South Wales Lancers]]. Many of the previous [[mounted infantry|mounted rifles]] were merged with the Lancers. A further four batteries of reserve artillery were raised in 1885, but disbanded in 1892. The permanent forces added units of [[submarine miners]] and [[mounted infantry]], which were also soon disbanded. The 1890s saw much restructuring, with many units formed and disbanded soon after, or merged with other units. |

||

| Line 64: | Line 66: | ||

==Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) (1803)==<!--Note: several redirects link to this section header.--> |

==Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) (1803)==<!--Note: several redirects link to this section header.--> |

||

| ⚫ | [[File:99th Regiment Memorial Anglesea Barracks.JPG|thumb|A memorial erected by the 99th Regiment of Foot at [[Anglesea Barracks]], [[Hobart]] to commemorate the soldiers of the regiment killed during the New Zealand Wars. This is the only monument built by British soldiers in Australia to commemorate their casualties.]] |

||

The settlement at Sydney was already 15 years old when then [[Governor]] [[Philip Gidley King]] received news from Europe of the outbreak of war between France and Great Britain on 18 May 1803. Concern was also growing over the number of French [[Exploration|explorers]] who were being sighted in the South Pacific. The [[Admiralty]] issued him with orders to secure any strategic locations within the southern station of the Pacific Ocean which might have been of use to France, and to prevent them falling into French possession. In response, he dispatched an expedition to settle at [[Risdon Cove]], in [[Van Diemen's Land]]. |

The settlement at Sydney was already 15 years old when then [[Governor]] [[Philip Gidley King]] received news from Europe of the outbreak of war between France and Great Britain on 18 May 1803. Concern was also growing over the number of French [[Exploration|explorers]] who were being sighted in the South Pacific. The [[Admiralty]] issued him with orders to secure any strategic locations within the southern station of the Pacific Ocean which might have been of use to France, and to prevent them falling into French possession. In response, he dispatched an expedition to settle at [[Risdon Cove]], in [[Van Diemen's Land]]. |

||

[[John Bowen (colonist)|John Bowen]], a 23 year old [[lieutenant]], had arrived in Sydney aboard [[HMS Glatton (1795)|HMS ''Glatton'']], on 11 March 1803. King considered him the right man for the task, and towards the end of August 1803, he left for Van Diemen's Land aboard the [[whaler]] ''[[HMS Albion (1802)|HMS Albion]]''. Accompanying him were three female and 21 male convicts, guarded by a company of the New South Wales Corps, as well as a small number of free settlers. A second supply ship, the ''[[Lady Nelson]]'', arrived on 8 September 1803, and HMS ''Albion'' arrived on 13 September 1803, subsequently settling Van Diemen's Land for the British. |

[[John Bowen (colonist)|John Bowen]], a 23 year old [[lieutenant]], had arrived in Sydney aboard [[HMS Glatton (1795)|HMS ''Glatton'']], on 11 March 1803. King considered him the right man for the task, and towards the end of August 1803, he left for Van Diemen's Land aboard the [[whaler]] ''[[HMS Albion (1802)|HMS Albion]]''. Accompanying him were three female and 21 male convicts, guarded by a company of the New South Wales Corps, as well as a small number of free settlers. A second supply ship, the ''[[Lady Nelson]]'', arrived on 8 September 1803, and HMS ''Albion'' arrived on 13 September 1803, subsequently settling Van Diemen's Land for the British. |

||

| ⚫ | [[File:99th Regiment Memorial Anglesea Barracks.JPG|thumb|A memorial erected by the 99th Regiment of Foot at [[Anglesea Barracks]], [[Hobart]] to commemorate the soldiers of the regiment killed during the New Zealand Wars. This is the only monument built by British soldiers in Australia to commemorate their casualties.]] |

||

At the same time [[David Collins (governor)|David Collins]] departed from England in April 1803, aboard [[HMS Calcutta (1795)|HMS ''Calcutta'']] with orders to establish a colony at [[Port Phillip]]. After establishing a short lived settlement at [[Sullivan Bay]], near the current site of [[Sorrento]], he wrote to King, expressing his dissatisfaction with the location, and seeking permission to relocate the settlement to the [[Derwent River, Tasmania|Derwent River]]. Realising that the fledgling settlement at Risdon Cove would be well reinforced by Collins' arrival, King agreed to the proposal. |

At the same time [[David Collins (governor)|David Collins]] departed from England in April 1803, aboard [[HMS Calcutta (1795)|HMS ''Calcutta'']] with orders to establish a colony at [[Port Phillip]]. After establishing a short lived settlement at [[Sullivan Bay]], near the current site of [[Sorrento]], he wrote to King, expressing his dissatisfaction with the location, and seeking permission to relocate the settlement to the [[Derwent River, Tasmania|Derwent River]]. Realising that the fledgling settlement at Risdon Cove would be well reinforced by Collins' arrival, King agreed to the proposal. |

||

Revision as of 14:33, 21 January 2012

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2010) |

Until Australia became a Federation in 1901, each of the six colonial governments was responsible for the defence of their own colony. From 1788 until 1870 this was done with British regular forces. In all, 26 British regiments served in the Australian colonies. Each of the Australian colonies gained responsible government between 1855 and 1890, and while the Colonial Office in London retained control of some affairs, and the colonies were still firmly within the British Empire, the Governors of the Australian colonies were required to raise their own colonial militia. To do this, the colonial Governors had the authority from the British crown to raise military and naval forces. Initially these were militias in support of British regulars, but British military support for the colonies ended in 1870, and the colonies assumed their own defence. The separate colonies maintained control over their respective militia forces and navies until 1 March 1901, when the colonial forces were all amalgamated into the Commonwealth Forces following the creation of the Commonwealth of Australia. Colonial forces, including home raised units, saw action in many of the conflicts of the British Empire during the 19th century. Members from British regiments stationed in Australia, saw action in India, Afghanistan, the Maori Wars of New Zealand, the Sudan conflict, and the Second Boer War in South Africa.

Despite an undeserved reputation of colonial inferiority, many of the locally raised units were highly organised, disciplined, professional, and well trained. For most of the time from settlement until federation, military defences in Australia revolved around static defence by combined infantry and artillery, based on garrisoned coastal forts, however in the 1890s, improved railway communications between all of the eastern mainland colonies (Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, and South Australia), led Major General Bevan Edwards, who had recently completed a survey of colonial military forces, to state his belief that the colonies could be defended by the rapid mobilisation of standard brigades. He called for a restructure of colonial defences, and defensive agreements to be made between the colonies. He also called for professional units to replace all of the volunteer forces.

By 1901, the Australian colonies had federated formally joined together to become the Commonwealth of Australia, and the federal government assumed all defensive responsibilities. The Federation of Australia came into existence on 1 January 1901 and as of that time the constitution of Australia stated that all defence responsibility was vested in the commonwealth government. Co-ordination of Australia wide defensive efforts in the face of imperial German interest in the Pacific Ocean was one of the main reasons for federation, and so one of the first decisions made by the newly formed Commonwealth government was to create the Department of Defence which came into being on 1 March 1901. From that time the Australian Army under the command of Major General Sir Edward Hutton came into being, and all of the colonial forces, including those who were already on active service in South Africa, transferred into the Australian Army. Badge changing ceremonies were held on the battlefield with colonial emblems being replaced with the Rising Sun Badge.[1]

Background

Australia was first formally claimed by Great Britain on 22 August 1770 by James Cook RN, however it was not settled until 26 January 1788 with the arrival of the First Fleet.[2] Frustrated in 1783 by the loss of their American colonies on the signing of the Treaty of Paris which formally ended the American Revolutionary War, the British sought a new destination for the transportation of convicts.[3] The fleet, consisting of 11 ships,[4] had arrived in Australia with around 750 convicts under the guard of marines, to establish a colony with convict labour at Port Jackson.[2]

Initially the colony was run as an open prison under the governance of Royal Navy Captain Arthur Phillip.[5] Until between the 1850s when the colonies were granted responsible government, and the 1870s when the last imperial troops were withdrawn, British regular troops constantly garrisoned the colonies. During their postings to Australia, most of the regiments rotated duties at the various colonies, and often had detachments located in geographically diverse locations.[6][7]

New South Wales (1788)

Accompanying the First Fleet to Port Jackson were three companies of marines totalling in all 212 men,[5] to guard the fledgling colony of Sydney and that of Norfolk Island, which had been established on 6 March 1788 to provide a food base and investigate supply of masts and flax for canvas for the Royal Navy. In 1790 the Second Fleet arrived, and the marines were relieved by a new force which was created specifically for service in the colony of New South Wales.[8] They were known as the New South Wales Corps – with an average strength of 550 men,[9] being less than a battalion they were given the generic title "Corps" rather than "Regiment"[citation needed] – with the first contingent of 183 men, under Major Francis Grose, arriving in June 1790.[8] They were subsequently expanded with further contingents from Britain as well free settlers, former convicts and marines who had discharged in the colony.[10] Throughout the mid-1790s the New South Wales Corps was involved in "open war" along the Hawkesbury River against the Daruk people.[10]

The first military forces raised in the colony of New South Wales were formed in June 1801, when "loyal associations" formed mainly from free settlers, were established in Sydney and Parramatta in repsonse to concerns about a possible uprising by Irish convicts.[10] Consisting of about 50 men each,[11] and receiving training from non commissioned officers of the New South Wales Corps, these associations are reputed to have been "reasonably efficient".[10]

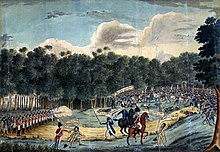

On 4 March 1804, the New South Wales Corps was called into action to put down the Castle Hill convict rebellion. Also known as the "Irish Rebellion", occurred when around 300 mostly Irish convicts,[12] led by Phillip Cunningham and William Johnson,[13] took up arms at Parramatta and marched towards the settlement at Hawkesbury.[14] In response, martial law was declared and a detachment of 56 men from the New South Wales Corps under the command of Major George Johnston,[15] marched all night to the centre of the rebellion, near the modern Sydney suburb of Rouse Hill, where they engaged with the main rebel force consisting of about 260 men in what was later called the "Battle of Vinegar Hill". A brief firefight followed, after which the crowd was dispersed. By the time that the fugitives had been chased down the following day, about 15 rebels had been killed and six were wounded, while another 26 had been captured.[15] Nine rebels were subsequently hanged.[16] During the engagement, locally raised militia personnel from the Sydney and Parramatta Loyal Associations had taken over the role of guarding strategic locations to free up men from the New South Wales Corps.[17]

Following the events of the Rum Rebellion, the New South Wales Corps was disbanded, reformed as the 102nd Regiment, and returned to England.[Note 1][18] At the same time, the various loyal associations were also disbanded.[11] To replace the New South Wales Corps, in 1810 the 73rd Regiment of Foot (MacLeod's Highlanders) arrived in the colony, becoming the first line regiment to serve in New South Wales under the Governorship of Lachlan Macquarie.[9][19] They served four years in New South Wales before relocating to Ceylon in 1814.[citation needed] The Highlanders were replaced by the 1st/46th (South Devonshire) Regiment of Foot, known as the "Red Feathers", who would serve in Australia until 1818.[20]

In March 1810, the New South Wales Invalid Company was formed for veteran soldiers and marines who were too old "to serve to the best of their capacity",[21] and served mainly as post guards, for the supervision of convicts and other government duties. It was composed of veterans of the 102nd, and other units from veteran soldiers.[22][7] By 1817 Lachlan Macquarie felt they were unable to perform even these duties, and recommended their disbandment. This was eventually done on 24 September 1822.[21] However, three further veterans companies were raised in Britain in 1825 for service in New South Wales, and stayed on duties until 1833.[21][22]

Also formed on 30 April 1810 was the Governor's Guard of Light Horse, mostly drawn from former convicts who had been of excellent behaviour during their sentences. Macquarie formed this unit, although not officially a regiment, to prevent the events of the Rum Rebellion from re-occurring. The Governor's Guard were mounted troops with the specific duty of being a private bodyguard for the Governor.[citation needed]

From 1817 until the withdrawal of British forces from Australia several British infantry regiments undertook garrison duties in Australia on a rotational basis.[9] The size of these forces varied over time. Initially the garrison was formed by only one regiment (battalion equivalent), however, in 1824 it rose to three. At its peak, in the 1840s, there were between four and six, although this fell to two in the early 1850s and then to one by the end of the decade.[23] In the 1860s, British forces were limited to mainly garrison artillery.[7] Although these units were primarily raised in Britain, any Australian born subjects who wished to pursue a military career were obliged to join the British Army, until the formation of locally raised volunteer militia units after responsible self government was granted in each of the Australian colonies. They often attached themselves to whichever regiments were on duty in their colony at the time, and sometimes left the Australian colonies when their regiments were posted elsewhere.

After the departure of the "Red Feathers", it was the turn of the 1st/48th (Northamptonshire) Regiment of Foot, who saw service in the Australian colonies from 1817 to 1824.[20] This regiment, better known as the "Heroes of Talavera" were variously posted at Sydney, Newcastle, Port Macquarie, Van Diemens Land and Parramatta, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel J. Erskine. They were the first of 13 "Peninsular Regiments" to see service in the Australian colonies. Having been involved in many distinguished actions of the Peninsular War including those at Talavera, Albuera, Salamanca and Vittoria, the Australian posting would have probably seemed a dull experience for the men,[citation needed] many of whom were hardened veterans.[24][Note 2] However the improving lifestyle of the colonies, and the relative peace after years of European battle appealed to many of the men of the 48th, with ten percent of their numbers eventually settling there following the end of their duties in 1824.[citation needed]

The 1st/3rd Foot The Buffs The East Kent Regiment, were the next Peninsular Regiment to be posted to the Australian colonies, and they began to arrive in New South Wales in 1822 to reinforce troops from the 1st/48th (Northamptonshire) Regiment of Foot.[25] The Buffs were divided into four detachments, and the first detachment began leaving Deptford for New South Wales in 1821. The second detachment left Deptford for Hobart in 1822. The third detachment (The Buffs Head Quarters) left Deptford for Sydney in 1823, arriving the same year.[citation needed] The fourth detachment arrived in Sydney in 1824 and were stationed at Port Dalrymple, Parramatta, Liverpool, Newcastle, Port Macquarie, Botany Bay and Bathurst. While in Australia, the Buffs were commanded by Lieutenant-Colonels William Stewart and C. Cameron.[26][27] The Regiment was reunited before being transferred to India,[6] arriving in Calcutta in 1827, however, following a trend begun during the departure of the 48th, many men wished to remain in New South Wales, and requested transfers to the 1st/57th Foot West Middlesex Regiment, who were arriving to replace the Buffs.[28]

In late 1823, with the 1st/3rd Foot The Buffs The East Kent Regiment primarily stationed throughout New South Wales, and the 1st/48th (Northamptonshire) Regiment of Foot due to be sent to Madras in India,[29] it was felt by the Colonial Office that more men would be required for the growing populations of New South Wales and Van Diemens Land. As a result, the 2nd/40th Foot Second Somersetshire Regiment were dispatched,[29] with detachments commanded by Lieutenant-Colonels H. Thornton and Valiant,[citation needed] sent to both Sydney and Hobart, where they were stationed for both garrison and guard duties until 1829.[20]

The 1st/57th Foot West Middlesex Regiment, known as the "Die Hards"[30] were next to arrive from 1825,[20] to replace the "Buffs". Under the command of Lieutenant-Colonels Shadforth, Allen and Carey, the "Die Hards" were initially stationed at Sydney and Hobart, but were also later sent to Westernport, Victoria (1829), and Port Albany, Western Australia (1828), following the establishment of those new colonies.

While the "Die Hards" were still stationed in Australia, the 1st/39th Foot Dorsetshire Regiment began arriving to also replace the "Buffs" in 1827.[28] This allowed for a staggered overlap of troops, with one regiment fully stationed while the other two swapped. Under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel P. Lindley, the regiment saw service in Hobart, Sydney, Western Australia and Bathurst[citation needed] before leaving in 1832 to see service in India.[31] The transportation of convicts to New South Wales came to an end in 1840 and as a result, the numbers of British troops in the colony dropped.[32]

With the outbreak of the Crimean War in 1854, a local voluntary force consisting of one troop of cavalry, one battery of artillery, and a battalion of infantry was raised.[33] The infantry force, consisting of six companies, was known as the Volunteer Sydney Rifle Corps.[34] Following the cessation of hostilities with Russia in Crimea, these forces struggled to maintain numbers and government funding.[33]

By 1855 New South Wales had been granted responsible self-government and increasingly took responsibility for its own affairs. The colony remained within, and was fiercely loyal to, the British Empire, and while the Colonial Office continued to take responsibility for matters such as foreign affairs, the decision was taken in London, that the Australian colonies would need to take responsibility for their own defence. Nevertheless, for the next 15 years, British infantry and artillery units would continue to garrison New South Wales, albeit in smaller numbers. Between 1856 and 1870, several different companies/batteries of the Royal Artillery served in New South Wales.[35] Likewise, members of the Royal Engineers Corps and Royal Corps of Sappers and Miners, Royal Staff Corps, Royal Commissariat Corps, Royal Medical Corps and the Royal Hospital Corps, who all saw service in New South Wales between 1856 and 1870.[citation needed]

In the early 1860s the Volunteer Sydney Rifle Corps ceased to exist, being subsumed into the 20 company-strong 1st Regiment, New South Wales Rifle Volunteers.[34] During the Maori Wars, although the colony had no official role, New South Wales contributed significantly to the 2,500 volunteers that were sent from Australia.[36]

In 1869 the decision to withdraw all British units in 1870 had been confirmed. By 1871 the withdrawal of British forces from New South Wales was completed,[37] and the local forces assumed total responsibility for the defence of New South Wales.[38] In order to meet this requirement, in 1870 the New South Wales government decided to raise a "regular" or permanent military force, consisting of two infantry companies and one artillery battery. The infantry companies were short lived, being disbanded in 1872,[36] however, the artillery battery, known as 'A' Field Battery, was successfully established in August 1871 to replace the units of the Royal Garrison Artillery that returned to Britain.[39] Nevertheless, the majority of the New South Wales military were part-time, volunteer forces,[Note 3] which around this time consisted of about 28 companies of infantry and nine batteries of artillery.[36] The entire force was reorganised by the Volunteer Regulation Act of 1867, which also gave provision for land grants in recognition of 5 years service.[37]

The 1870s saw major improvements to the structure and organisation of New South Wales' colonial forces. Land grants for service were abolished, and partial payments introduced. 1876 saw a second permanent artillery battery established, and a year later a third was added. In 1877 Engineers Corps and Signals Corps were established, in 1882 a force of naval artillery volunteers, and in 1891 the Commissariat and Transport Corps, later to be known as the Army Service Corps were raised.

When the government of New South Wales received news in February 1885, of the death of General Charles Gordon at Khartoum during the short-lived British campaign against the Dervish revolt in the eastern Sudan,[41] they offered the British forces there the service of New South Wales artillery batteries, infantry and ambulance detachments.[citation needed] The offer was accepted, and within two weeks a force of 30 officers and 740 men comprising an infantry battalion, with artillery and support units was enrolled, re-equipped and dispatched for Africa. They were farewelled from Circular Quay in Sydney on 3 March 1885 by an enormous public gathering and marching bands.[42]

The New South Wales Sudan contingent arrived at Suakin on the Red Sea on 29 March 1885.[43] There they joined Lieutenant General Gerald Graham's two British brigade's efforts against Osman Digna. Within a month of arriving, the New South Wales detachment had seen action at Tamai,[44] becoming the first Australian raised military force to do so. By May 1885, the campaign had been reduced to a series of small skirmishes, the most significant of which for the New South Wales contingent came at Takdul on 6 May.[45] They subsequently returned to Sydney by 23 June 1885.[42] Despite their service, and their engagements at Tamai and Takdul, the New South Wales Sudan contingent was ridiculed by the media upon their return to New South Wales, as having done nothing to aid the war effort. Many cartoons appeared parodying the force as lazy, or as tourists.[citation needed] Nevertheless, the contingent's efforts were recognised with an official battle honour – "Suakin 1885" – which was the first battle honour awarded to an Australian unit.[43]

In 1885 it was decided to raise a volunteer corps of cavalry who were to also be partially paid, and had uniforms and weapons supplied, although they had to provide their own horse and equipment. They were eventually formed as a light horse unit and were known as the New South Wales Lancers. Many of the previous mounted rifles were merged with the Lancers. A further four batteries of reserve artillery were raised in 1885, but disbanded in 1892. The permanent forces added units of submarine miners and mounted infantry, which were also soon disbanded. The 1890s saw much restructuring, with many units formed and disbanded soon after, or merged with other units.

Full volunteers were again instituted in 1895. These units started to often have affiliations with expatriate groups, and names such as the Scottish Rifles, the Irish Rifles, the St. George's Rifles, and the Australian Rifles, reflected this. By 1897, there was also the First Australian Volunteer Horse and the Railway Volunteer Corps, and a "National Guard" of volunteer veterans. By 1900 the Canterbury Mounted Rifles, the Civil Service Corps, the Drummoyne Volunteer Company, the Army Nursing Service Reserve and Army Medical Corps had also been added.

Hostilities commenced in the Second Boer War in October 1899, and all the Australian colonies agreed to send troops in support of the British cause. The First New South Wales Contingent arrived in South Africa in November 1899. New South Wales' contribution was the largest amongst all of the colonies,[46] with a total of 4,761 men being sent prior to Federation either at the colony's or Imperial expense. A further 1,349 were sent later as part of Commonwealth forces. The total size of the New South Wales contingent over the entire war was 6,110 troops of all ranks,[46] which was broken down into 314 officers, and 5,796 other ranks who served in the New South Wales Lancers, and New South Wales Mounted Rifles.[citation needed]

A survey of New South Wales' military forces on 31 December 1900, the day before Federation, found that the forces consisted of 505 regular officers, 130 volunteer officers, 9295 regulars and 8833 volunteers of other ranks, 26 nurses, and 1906 civilian rifle club members.

Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) (1803)

The settlement at Sydney was already 15 years old when then Governor Philip Gidley King received news from Europe of the outbreak of war between France and Great Britain on 18 May 1803. Concern was also growing over the number of French explorers who were being sighted in the South Pacific. The Admiralty issued him with orders to secure any strategic locations within the southern station of the Pacific Ocean which might have been of use to France, and to prevent them falling into French possession. In response, he dispatched an expedition to settle at Risdon Cove, in Van Diemen's Land.

John Bowen, a 23 year old lieutenant, had arrived in Sydney aboard HMS Glatton, on 11 March 1803. King considered him the right man for the task, and towards the end of August 1803, he left for Van Diemen's Land aboard the whaler HMS Albion. Accompanying him were three female and 21 male convicts, guarded by a company of the New South Wales Corps, as well as a small number of free settlers. A second supply ship, the Lady Nelson, arrived on 8 September 1803, and HMS Albion arrived on 13 September 1803, subsequently settling Van Diemen's Land for the British.

At the same time David Collins departed from England in April 1803, aboard HMS Calcutta with orders to establish a colony at Port Phillip. After establishing a short lived settlement at Sullivan Bay, near the current site of Sorrento, he wrote to King, expressing his dissatisfaction with the location, and seeking permission to relocate the settlement to the Derwent River. Realising that the fledgling settlement at Risdon Cove would be well reinforced by Collins' arrival, King agreed to the proposal.

Collins arrived at the Derwent River on 16 February 1804, aboard HMS Ocean. The settlement that Bowen had established at Risdon Cove did not impress Collins, and he decided to relocate the settlement 5 miles (8.0 km) down river, on the opposite shore. They landed at Sullivans Cove on 21 February 1804, and created the settlement that was to become Hobart, making it the second oldest established colony in Australia. Soon after the establishment of the settlement, Collins decided that coastal defence was needed. A redoubt was dug not far from the settlement, and two ship's guns were placed within.

Before the settlement at Risdon Cove had been abandoned, one of the most violent conflicts between British forces and Australian Aborigines is alleged to have occurred. The facts of this event are still disputed by historians and the descendants of the Tasmanian Aborigines, however it is alleged that on the morning of 3 May 1804, a food hunting party of approximately three hundred crested the heavily wooded hills above the Risdon Cove settlement, looking for kangaroo, in what is now considered to be part of the Oyster Bay tribe's traditional hunting grounds. It is supposed that both the Marine sentries, and the hunting party surprised each other. It is not clear how the engagement began, with differing accounts being given.

It does seem that feeling threatened by such an overwhelmingly large group, the Marines fired upon the Aborigines in an unprovoked attack. A convict by the name of Edward White claimed to have seen this. Armed with only spears and clubs, the Aboriginals were outdone by the firepower of the Marines who were armed with the Brown Bess smooth bore, muzzle loading musket, many of whom were experienced troops from conflicts in India and the Americas.[citation needed] It is claimed that between three and 60 of the Aboriginals were killed.[47][48]

When Governor Lachlan Macquarie toured the Hobart Town settlement in 1811, he was alarmed at the poor state of defence, and the general disorganisation of the colony. Along with planning for a new grid of streets to be laid out, and new administrative and other buildings to be built, he commissioned the building of Anglesea Barracks, which opened in 1814, and is now the oldest continually occupied barracks in Australia.

The New South Wales Corps were also relieved from Van Diemen's Land when they returned from New South Wales in 1810, and the 73rd Regiment of Foot (MacLeod's Highlanders), rotated duties between Sydney and Hobart.[citation needed] These were likewise replaced in 1814 by the 1st/46th (South Devonshire) Regiment of Foot, the so called "Red Feathers", who undertook a campaign undertook a series of operations against busherangers until 1818.[49]

By 1818, the Mulgrave Battery had been built on Castray Esplanade, on the southern side of Battery Point upon the orders of Lieutenant Governor William Sorell. Now the colony had two basic fortifications.

The period of 1828 until 1832 was a dark one in the history of Van Diemen's Land. The rising friction and continuing conflicts over land access between the indigenous Tasmanian Aborigines and the British settlers, breaches of each other's laws and morals, and the cycle of killings and revenge killings,[citation needed] led to a declaration of martial law by Lieutenant Governor George Arthur.[50] British regiments were in open conflict with the Aboriginals in what has since been dubbed the Black War. In 1830, during the Black Line incident, European settlers tried to round up the Tasmanian Aboriginals in an unsuccessful attempt to isolate them,[51] and prevent further conflicts between the two groups.[citation needed]

In 1838 plans were drawn up for a more elaborate network of coastal fortifications. Money did not permit all of the batteries to be established, but work was begun on the Queens Battery, located at the site of the regatta ground on the Queens Domain. The battery was set back by delays and funding problems, and was not completed until 1864.

By 1840, the newly arrived commander of the Royal Engineers, Major Roger Kelsall, was alarmed to discover how inadequately defended the now growing colony was. He drew up plans for the expansion of the Mulgrave Battery, and an additional fortification further up the slopes of Battery Point. Work began the same year using convict labour, and soon the Prince of Wales Battery, consisting of ten guns, was completed. Despite these improvements, the was badly sited. As a result, at the height of the Crimean War in 1854, a third battery, known as the Prince Albert Battery was completed even higher behind the Prince of Wales Battery. Battery Point now had three firing positions, along with the Queens Battery upon the Queens Domain.

Following the decline of British military presence in Tasmania, the Governor of Tasmania felt the need to establish military forces capable of defending the colony. In 1859 two batteries of "volunteer" artillery, the Hobart Town Artillery Company and the Launceston Volunteer Artillery Company, were formed. Twelve companies of "volunteer" infantry were also raised. Although the infantry companies were disbanded in 1867, the artillery was increased by one battery.

1870 saw the complete withdrawal of British forces from Tasmania, which left the colony virtually defenceless. It had also highlighted the state of decay the existing fortresses had fallen in to. It had been decided the Prince of Wales and Prince Albert Batteries were inadequate for the defence of the town. By 1878 both had been condemned, and were dismantled by 1880. In 1882 the sites were handed over to Hobart City Council for use as public space, although the tunnels and subterranean magazines remain. Most of the stonework was removed and reused in the construction of the Alexandra battery further to the south.

The arrival of three Russian warships, Africa, Plastun, and Vestnik in 1872 caused a great deal of alarm in the colony. Britain and its empire had only been at war with the Russians 16 years previously. The colony was defenceless, had the Russians had hostile intent. Luckily they were on a good will mission, however, it cause a great deal of debate about the state of the colony's defences. Plans were made for the establishment of volunteer forces.

In 1878 the Tasmanian Volunteer Rifle Regiment was raised in both the north and south of the colony. These were raised as Ranger Infantry units. By 1882 their strength was 634 men. By 1885 it had grown to 1,200 men, the maximum permitted by law at a time of peace. However, by 1893, an additional "auxiliary" force of 1,500 had also been raised and three years later the regiment consisted of three battalions, numbered consequectively, which were based in Hobart, Launceston and in the north west.

Construction of fortifications had been considered as early as 1840, however no serious work was carried out until 1881 when the Kangaroo Bluff Battery was begun. It was completed the following year with the arrival of two 14 tonne cannons from England. The first shots were fired on 12 February 1885.

In 1899 the Tasmanian Colonial Military Forces responded to the request for military assistance in South Africa. The initial request was made for two of the colony's three Ranger Infantry units. Colonel Legge, the commandant of the Tasmanian Colonial Military Forces, sought to also establish a mounted reconnaissance unit, and toured the colony. He was very impressed by the shooting and riding skills of many of the colony's wealthy young farm boys, and formed a Tasmanian Imperial Bushmen unit from them.

A Tasmanian colonial contingent was sent to the Second Boer War, consisting of the 1st and 2nd Tasmanian Bushmen. These mounted infantry units were primarily made up of volunteers who had good bushcraft, riding and shooting skills.[citation needed] The first two Victoria Crosses awarded to Australians in that conflict were earned by Private John Bisdee and Lieutenant Guy Wylly, both members of the Tasmanian Bushmen, in action near Warm Bad in 1900.[52]

On 31 December 1900, the day before Federation, a survey of the strength of colonial forces found that the Tasmanian colonial forces consisted of 131 regular and 113 part-paid or volunteer officers, and 2605 regular, and 1911 part-paid or volunteer men of other ranks. Upon Federation, all of the Australian colonial forces came under the control of the Federal Government of Australia. As a result, the Tasmanian Mounted Infantry units were redesignated as the 12th Australian Light Horse Regiment (12LHR) in 1903,[53][Note 4] while the three battalions of the Tasmanian Volunteer Rifle Regiment were re-designated as part of the Citizens Military Force becomng the Derwent Infantry Regiment (Hobart), the Launceston Regiment (Launceston), and the Tasmanian Rangers (North West).[55]

Members of the Royal Engineers Corps & Royal Corps of Sappers and Miners, Royal Staff Corps, Royal Commissariat Corps Royal Medical Corps and the Royal Hospital Corps, all also saw service in Tasmania between 1856 and 1870.

Swan River Colony (Western Australia) (1829)

Following its first sighting by Dirk Hartog, on 26 October 1616, the coast of Western Australia had been explored and charted by many Europeans prior to its eventual settlement. Most of these explorers had felt that the coast's resources were inadequate to support a permanent settlement. That changed in the early 19th century, when the fear of French settlement in the area drove British authorities to establish their own colony. In 1827, Captain James Stirling sighted the area surrounding the Swan River as being suitable for agriculture, and upon his return to England in July 1828, lobbied for the establishment of a free settler colony, unlike the penal settlements of eastern Australia. The British Government assented, and a fleet led by Charles Fremantle, aboard HMS Challenger returned along with three other vessels, arriving to establish the Swan River Colony on 2 May 1829. The name of the colony was changed to Western Australia in 1832.

Following the establishment of the Swan River Colony, a detachment from 2nd/40th Foot Second Somersetshire Regiment who were garrisoned in Sydney at the time, was dispatched to the new colony. Following them, were detachments from most of the regiments that were also serving in New South Wales.[citation needed] In addition to the British garrison, a small locally-raised unit was established known as the Swan River Volunteers; all settlers between 15 and 50 years of age were obligated to serve and were required to supply their own weapons.[34]

In 1861 the British garrison was withdrawn from Western Australia, and so the local Western Australian Volunteer Force was raised, primarily from Perth, Fremantle and Pinjarra. Training was hard to come by, and although the unit was enthusiastic, records show that discipline and poor attendance was a problem. By January 1869, the government had issued tough regulations to training and attendance, and although the unit was made up of volunteers, allowed for payments to be made to those who met a minimum requirement of attendance. By this time, Pinjarra had also raised a Pinjarra Mounted Volunteers unit of skilled horsemen.

Although the situation improved, the unit was still very amateurish. A reorganisation followed, and by 17 June 1872 the Metropolitan Rifle Volunteers were formed, with companies in Fremantle, Guildford, Albany, Geraldton, Northampton, York, and in the Wellington District. By 1875 the officers of the Western Australian Volunteer Force were required to take examinations, prove their suitability for the promotion, and all ranks undertook both practical and field training. Corps were brought together annually, normally over Easter to practice manoeuvres, and had become highly organised.

In February 1893, the Permanent Force Artillery Company was raised to garrison forts at Albany, as the Royal Artillery was being withdrawn. In November 1893 the infantry units of Perth, Fremantle and Guildford were amalgamated to form the 1st Infantry Volunteer Regiment. Combined with the existing companies of the Western Australian Volunteer Force, the new regiment became part of the newly formed Western Australian Defence Force.

From 1893 to 1898 an annual camp was held in the vicinity of Perth, bringing together most of the force, although units from remote regions usually undertook the same training in isolation. Although lacking the advantage of training as part of a larger force, they still undertook these training camps with a high level of professionalism. The Perth camp had been organised for both 1899 and 1900, but these camps were cancelled as the Western Australian Defence Force was dispatched to serve against the Boers in South Africa.[citation needed] During the conflict, 349 men were dispatched from Western Australia at state expense, while a further 574 were deployed and paid for through Imperial funds. Another 306 were dispatched as Commonwealth troops later after 1901.[46] One member of the Western Australian Mounted Infantry, Lieutenant Frederick Bell, received the Victoria Cross during the conflict.[52]

By the time the men had returned from war, Australia had federated and become the Commonwealth of Australia, and the Western Australian Defence Force, which then consisted of one mounted infantry regiment, two field batteries, one garrison artillery company and an infantry brigade consisting of five battalions, were amalgamated into the newly formed Australian Army. On 31 December 1900, the day before Federation, a survey of the strength of colonial forces found that the Western Australian colonial forces consisted of 140 regular and 135 part-paid or volunteer officers, and 2553 regular, and 2561 part-paid or volunteer men of other ranks.

South Australia (1836)

South Australia was the only British colony in Australia which was not a convict colony. It was established as a planned free colony, and began on 28 December 1836.[citation needed] As such, garrisons were not required as prison guards, like in the other colonies. However, Governor John Hindmarsh was escorted on the HMS Buffalo by a contingent of nineteen Royal Marines. They were assigned to protect him and left South Australia when he departed the colony on the HMS Alligator on 14 July 1838.[56] A lack of any form of defence however, led to the creation of the Royal South Australian Volunteer Militia in 1840, although it was disbanded in 1851; for the final six years of its existence it had been a force that had existed on paper only.[34]

The idea of self-support was entirely ingrained in the foundation of the South Australian colony though, and so in 1853 the Militia Act (1853) was passed, which allowed for compulsory enlistment of men between the ages of 16 and 46, although this option was never pursued. On 4 November 1854, a new attempt was made to raise local militia forces in South Australia. The government proclaimed a general order that established the South Australian Volunteer Militia Force, which was to be organised into two battalions, each consisting of six companies of between 50 and 60 men, which would be known as the Adelaide Rifles. The men received 36 days training, and then returned to their civilian jobs until needed. This force was short lived though, being disbanded upon the end of the Crimean War in 1856.[57]

However, the colonial government felt uneasy about being undefended. The Volunteer Force was reformed in 1859, and soon numbered 14 companies.[57] By the following year, the numbers had increased to 45 companies with a total of 70 officers and 2,000 men of other ranks. On 26 April 1860, the Adelaide Regiment of Volunteer Rifles was formed. In 1865 South Australia became the first state to introduce partially paid volunteers, which was a system all of the other colonies were soon to follow. This was brought about by the enacting of the Volunteer Act (1865) which divided all military forces into active and reserve forces. Due to organisational problems and lack of equipment, the Adelaide Regiment of Volunteer Rifles was again disbanded in early 1866,[57] only to be reformed again in May 1866. By 16 November 1867, the Adelaide Regiment of Volunteer Rifles had been re-designated as the "Prince Alfred's Rifle Volunteers" following the Duke of Edinburgh's visit to Australia,[57] but lack of funding saw them disbanded. A company of expatriate Scottish immigrants had formed The Scottish Company in 1865, and reformed as The Duke of Edinburgh's Own on 18 November 1867.[citation needed]

The outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in France on 19 July 1870, led the South Australian Governor, Sir James Fergusson, to conduct a review of the colony's defences. He determined to reorganise the force into two battalions of 500–600 men, two artillery batteries, and four troops of cavalry. However his proposals received little backing from the colonial parliament, and were rejected by newly re-elected Premier John Hart. Some politicians felt it would help alleviate the high unemployment the colony was suffering at the time, but the majority felt the enormous cost outweighed the potential benefits. Once again the issue of funding stood in the way of South Australia having an efficient and ready regular military force.[citation needed]

The issue continued to be debated until 1875 when interest in military expansion was renewed amongst the colonial politicians. The government had been quite unstable for the first five years of the 1870s, but settled in 1875, allowing for more stable planning. Once again affairs of empires played a part. Russia was once again being perceived as a threat by all of the colonial governments following the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78. Politicians came under pressure from the press and campaign groups to expand the defensive capacity of the colony.[57]

Finally in May 1877, the South Australian Volunteer Military Forces was reformed consisting primarily of 10 companies of the Adelaide Rifles. The success of raising those units did not stop the political arguments over the issue with wrangling between Governor Sir William Jervois and Premier John Colton temporarily suspending further development.[citation needed] Despite all of the political setbacks, the Adelaide Rifles had soon grown to 21 companies, and on 4 July 1877 a second battalion was formed.[57] The second battalion comprised the companies from Mount Gambier, Unley, and Port Pirie together with the Duke of Edinburgh's Own of Prince Alfred Rifle Volunteers. Training intensified briefly for the duration of the Russo-Turkish War, and then resumed at normal levels, with the 2nd Battalion being amalgamated with the 1st Battalion.[citation needed]

By 1885, the second battalion was again reformed, consisting of the same companies as previously, and a third battalion was raised in 1889, only to be disbanded in 1895.[57] Up until 1896, all South Australian units trained only once a year at Easter. The commitment of the men, and constant restructuring and reorganising were in direct response to perceived threats to the colony.[citation needed]

Upon the outbreak of hostilities in the Second Boer War, many men from various South Australian units volunteered to participate with the Australian contingent.[57] Any regiments whose men participated later received King's Colours and battle honours.[58] The colony contributed 1,036 personnel to the conflict under its own banner and another 490 were sent as part of Commonwealth forces.[46]

On 31 December 1900, the day before Federation, a survey of the strength of colonial forces found that the South Australian colonial forces consisted of 141 regular and 135 part-paid or volunteer officers, and 2847 regular, and 2797 part-paid or volunteer men of other ranks.[citation needed] Following South Australia's admission to the Commonwealth of Australia, all of the South Australian forces were drawn into the Australian Army. The 1st Battalion of the Regiment of Adelaide Rifles being redesignated as the 10th Australian Infantry Regiment (Adelaide Rifles), the 2nd Battalion became the South Australia Infantry Regiment, G Company became South Australia Scottish Infantry (Mount Gambier), and 'H' Company Scottish became 'G' Company (Scottish) South Australia Infantry Regiment.[citation needed]

Victoria (1851)

The first attempt to establish a settlement in what is now Victoria was made by David Collins departed from England in April 1803, aboard HMS Calcutta with orders to establish a colony at Port Phillip. It was short lived, as he was unhappy with the location and the inability of his small Marine contingent to defend the site from aggressive local Aborigines, and he removed it to Van Diemen's Land. Several journeys and explorers passed the northern coast of Bass Strait in the interim, but it was not until John Batman journeyed from Van Diemen's Land in 1835 to establish a farming community at what was to become Melbourne that the new colony was established. The new settlement's prime locality between New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land, and the natural resources of the area saw it grow rapidly. Initially the settlement was governed directly by Sydney, but by 1840, it was proposed that it should be self governing. This was achieved on 1 July 1851.

As with New South Wales, in Victoria the Crimean War served as a catalyst for the raising of volunteer forces. At this time two units were formed, these were the Melbourne Volunteer Rifle Regiment and the Geelong Volunteer Rifle Corps.[34] Further expansion, primarily through private enterprise, resulted in the addition of cavalry, artillery, engineer, torpedo and signal units.[citation needed]

In late December 1854 the newly formed Victorian Government faced their first crisis. Three years earlier, in 1851, gold had been discovered in Ballarat, and soon after in Bendigo triggering the Victorian gold rush. The government imposed heavy mining taxes, which caused a miners revolt, culminating in the Eureka Stockade.[31] About 1,000 miners fortified a position, and at 3:00 am on 3 December 1854, a party of 276 members from the 1st/12th and 2nd/40th Regiments[31] supported by Victorian police, under the command of Captain John Thomas, approached the Eureka Stockade and a battle ensued.[59] The police took up holding positions on two sides of the stockade, with a further unit of mounted police held in reserve. On a third side mounted members of the 2nd/40th pressed in, supported by a combined storming party made up from members of the 2nd/40th and the 1st/12th Foot East Suffolk which approached from the north and south.[60] The miners, about 150 strong – of whom 100 were armed – were no match for the military and they were routed in less than 15 minutes,[61] with six soldiers and 34 miners being killed.[31] A contingent of the 1st/99th Foot Wiltshire Duke of Edinburgh Regiment, then serving in Tasmania, was dispatched to aid them, however they were not required.[citation needed]

In the 1850s Melbourne was the headquarters of the Australia and New Zealand Military Command, and for a brief period in the early 1860s, Melbourne was the headquarters of the Royal Navy's Australia Station. This period also saw the Victorian Government pass the Volunteer Act (1863), authorising the raising of voluntary military forces.

1870 saw the creation of Victoria's first permanent Artillery Corps, which was essentially created to garrison the fortifications throughout the colony following the final departure of British Units garrisoned in Victoria. The Corps never exceeded 300 men in strength.

From the 1870s onwards, the Victorian military expanded and further developed at a steady rate. Increased training led to better efficiency and high standards of the men. Increased numbers of professional soldiers were developed alongside a well maintained militia of citizens.

In 1884 a new system of paid militia who served for a fixed term replaced the old system of volunteers. Although the service remained part time, allowing troops to continue civilian employment, a minimum number of days was set. The following year, the Victorian Mounted Rifles were formed, primarily recruiting in rural areas where men had alrady established horsemanship skills and thus did not need further training. These men were required to provide and maintain their own horse. In 1888, the Victorian Rangers, a rural infantry unit, was also raised. Both rural units were not paid well, but did receive small allowances. It seems that members of rural rifle clubs formed the basis of both of these units.

In December 1892, men of the Echuca Company of the Victorian Rangers nearly sparked an inter-colonial incident between New South Wales and Victoria, by accepting a polite invitation to cross the colonial border of the Murray River to nearby Moama, to attend a patriotic march. However, crossing the border in uniform and under arms would have legally constituted an "invasion", and would have been in contravention of the military law of both colonies. Despite the obvious social context of the event, and the seemingly innocent nature of the Rangers' acceptance, the incident, now referred to as the "border event" upset members of both colony's governments, who were seemingly both opposed to either colony allowing troops from the other to enter their territory. The event was defused without incident, but served to highlight how tense the colonies were about defence at the time. Eventually permission was granted for the men to enter New South Wales, and they performed marches and manoeuvres in front of a large reception.

The Victorian Scottish Regiment was formed in 1898.

Upon the outbreak of the Second Boer War in South Africa on 12 October 1899, men volunteered for active service from every Australian colony. Victoria's contribution was second only to New South Wales in size,[46] and comprised 193 officers and 3372 men of other ranks. The Victorian contingent were involved in a remarkable victory when they routed the Boers at Johannesburg on 29 May 1900.[citation needed] One Victorian, Lieutenant Leslie Maygar, received the Victoria Cross during the conflict.[52]

On 31 December 1900, the day before Federation, a survey of the strength of colonial forces found that the Victorian colonial forces consisted of 394 regular and 301 part-paid or volunteer officers, and 6050 regular, and 6,034 part-paid or volunteer men of other ranks. Shortly after Federation, on 1 March 1901,[62] the units of the Victorian forces became units of the Australian Army.

Queensland (1859)

Queensland was established by Letters Patent from Queen Victoria, on 6 June 1859. Prior to this time, the area that constitutes Queensland was formally part of the colony of New South Wales, and therefore came under New South Wales' military protection. After being granted self government, Queensland immediately set about raising militia forces. By March 1860, a troop of volunteer mounted rifles had been raised. They were soon joined by units of infantry and cavalry, and later supplemented by artillery. These men were all volunteers, but unlike the other Australian colonies of the time, they received government subsidies and grants for the purchase of equipment and ammunition. This was soon broadened to include grants of 50 acres (200,000 m2) of land upon completion of five years of consecutive service.

By 1876, the forces amounted to an inadequate 412 men in total. Steps were taken to improve the situation, including the passing of the Volunteer Act (1878), which encouraged citizens to undertake training, and saw the numbers of men increase to 1219 by 1880.

British forces had been stationed at Port Albany, and on Cape York between 1865 and 1867, because of the recognised strategic importance of Torres Strait, New Guinea and King George's Sound. After their withdrawal, Queensland maintained a token force there, but it was widely recognised as inadequate to prevent any serious threat. An administrative centre and a more serious force was raised to be stationed upon Thursday Island in 1877.

Like the other Australian colonies, Queensland's government was not satisfied by the volunteer system, and aimed to replace it. A Military Committee of Inquiry was established to determine the best alternatives, and found that the service lacked cohesion and discipline. They recommended a combination of partially paid militia with volunteer corps formed to support them, with all male inhabitants liable for service.[citation needed] In 1880 payments to volunteers for attending annual camps were stopped.[63] Four years later the Volunteer Act was repealed and under the provisions of the Queensland Defence Act a "dual system" was established which consisted of paid militia units based in metropolitan areas alongside unpaid volunteer units in rural areas, supported by a reserve of officers.[63]

Around the same time the Queensland government felt alarmed by the threat of the expansion by the German colony of German New Guinea, and felt that by securing the southeastern quarter of the island of New Guinea, they could provide more safety for shipping through the Torres Strait. Queensland Premier Thomas McIlwraith ordered Henry Chester, who was the then police magistrate on Thursday Island, to proceed to Port Moresby and take possession of it for Great Britain. He did so, arriving on 4 April 1883, without approval from the Colonial Office, and much to the astonished consternation of the British Government which was firmly opposed to further colonial expansion, raised the Union Flag proclaiming the British colony of the Territory of Papua.

The British government initially repudiated the action, but a firmer commitment by the Australian colonial governments finally secured a British Protectorate over southern New Guinea (Papua) in October 1884, and it was declared an official British protectorate on 6 November 1884. Causing much consternation in London, an astute Germany annexed the northern portion two weeks later, expanding Kaiser-Wilhelmsland.

In 1884, the recommendations of the Military Committee of Inquiry were enacted, and a smaller, more cohesive permanent force was established, with volunteer support.

In July 1899, as tensions between British and Boer settlers in South Africa grew, Queensland pledged a force of 250 men in the event of war.[64][65] The Second Boer War subsequently broke out on 11 October 1899 and over the course of the conflict Queensland contributed the third largest force of all the colonies,[46] consisting of 733 troops provided at State expense and 1,419 at Imperial expense,[46] who served in the Queensland Mounted Infantry and Queensland Bushmen.[citation needed] Following Federation, a further 736 Queenslanders would serve in Commonwealth units,[46] making a total Queensland contribution of 149 officers, and 2739 men of other ranks.[citation needed] Troops from the Queensland Mounted Infantry were involved in the first significant Australian action of the war when they took part in an attack on a Boer "laager" at Sunnyside on 1 January 1900,[66] during which they lost two men killed and two wounded.[67]

On 31 December 1900, the day before Federation, a survey of the strength of colonial forces found that Queensland's colonial forces consisted of 810 regular and 291 part-paid or volunteer officers, and 5035 regular, and 3737 part-paid or volunteer men of other ranks.[citation needed] As with all of the Australian colonies, the forces of Queensland automatically transferred to Commonwealth control on 1 March 1901.[62]

See also

- Colonial navies of Australia

- List of British Army regiments that served in Australia between 1810 and 1870

Notes

- Footnotes

- ^ 265 men from the 102nd transferred to the 73rd and 111 went to the New South Wales Invalid Company. 80 members took discharge in Australia.[18]

- ^ Upon its arrival in Sydney in 1817, the 48th had over 200 veterans of the Napoleonic wars in its ranks.[24]

- ^ During the colonial period, the term "volunteer" was applied to military units that were unpaid. Regular units, while made up men who were also volunteers in the sense that they were not conscripts, were paid, full-time soldiers. Such units were more frequently labled as "permanent" rather than "regular" in the language of the time period.[40]

- ^ Not to be confused with the 12th Light Horse Regiment which was formed in 1915 in New South Wales for service during the First World War.[54] The Tasmanian unit, which had been formed in 1903, is not a predecessor of the the 12th Light Horse Regiment, AIF, and during the war it contributed a squadron to the 3rd Light Horse Regiment before being later re-raised as the 22nd Light Horse Regiment.[53]

- Citations

- ^ Laffin & Chappell 1996, p. 8.

- ^ a b Stanley 1986, p. 9.

- ^ Ferguson 2003, p. 102.

- ^ Ferguson 2003, p. 103.

- ^ a b Grey 2008, p. 8.

- ^ a b Grey 2008, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Dennis et al 1995, p. 122.

- ^ a b Dennis et al 1995, p. 433.

- ^ a b c Grey 2008, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d Stanley 1986, p. 18.

- ^ a b Kuring 2004, p. 11.

- ^ Grey 2008, p. 11.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1998, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 2.

- ^ a b Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 3.

- ^ Grey 2008, p. 12.

- ^ Grey 2008, p. 21.

- ^ a b Kuring 2004, p. 5.

- ^ Dennis et al 1995, p. 121.

- ^ a b c d Kuring 2004, p. 10.

- ^ a b c Chapman, M. & Chapman, B (2010). "Royal New South Wales Veteran Corps". Ancestry.com. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Stanley 1986, p. 28.

- ^ Grey 2008, p. 14.

- ^ a b Grey 2008, p. 14.

- ^ Sargeant 1995, p. 3.

- ^ Stanley 1986, p. 32.

- ^ Sargeant 1995, pp. 5–6.

- ^ a b Sargeant 1995, p. 13.

- ^ a b Sargeant 1995, p. 6.

- ^ Sargeant 1995, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d Odgers 1988, p. 17.

- ^ "Colonial period, 1788–1901". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 21 January 2012.

- ^ a b Grey 2008, p. 22.

- ^ a b c d e Kuring 2004, p. 12.

- ^ Stanley 1986, p. 79.

- ^ a b c Kuring 2004, p. 14.

- ^ a b Grey 2008, p. 23.

- ^ Odgers 1988, p. 30.

- ^ "A Field Battery, Royal Australian Artillery". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ^ Kuring 2004, p. 15.

- ^ Grey 2008, p. 48.

- ^ a b Grey 2008, p. 49.

- ^ a b Kuring 2004, p. 16.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1998, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 53.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Grey 2008, p. 58.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1998, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Parry, Naomi. "Many deeds of terror: Windschuttle & Musquito". Evatt Foundation. Archived from the original on 18 February 2011. Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ^ Stanley 1986, p. 26.

- ^ Dennis et al 1995, p. 4.

- ^ Dennis et al 1995, p. 123.

- ^ a b c Odgers 1988, p. 43.

- ^ a b Festberg 1972, p. 54.

- ^ "12th Light Horse Regiment". Australian War Memorial. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- ^ Harris, Ted. "12/40 RTR". Digger History. Archived from the original on 29 April 2010. Retrieved 21 January 2012.

- ^ "HMS Buffalo 1836 – Pioneers and Settlers Bound for South Australia". State Library of South Australia. 7 October 1913. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kearney 2005, p. 18.

- ^ Dennis et al 1995, p. 86.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1998, p. 26.

- ^ Stanley 1986, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1998, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b Kuring 2004, p. 30.

- ^ a b Grey 2008, p. 45.

- ^ Laffin & Chappell 1996, p. 4.

- ^ Grey 2008, p. 56.

- ^ Grey 2008, p. 59.

- ^ Coulthard-Clark 1998, pp. 63–64.

References

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (1998). Where Australians Fought: The Encyclopaedia of Australia's Battles (1st ed.). St Leonards, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1864486112.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dennis, Peter; Grey, Jeffrey; Morris, Ewan; Prior, Robin (1995). The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History (1st ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195532279.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Ferguson, Niall (2003). Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World. Camberwell, Victoria: Penguin. ISBN 9780141037318.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Festberg, Alfred (1972). The Lineage of the Australian Army. Melbourne, Victoria: Allara Publishing Pty Ltd. ISBN 9780858870246.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Grey, Jeffrey (2008). A Military History of Australia (3rd ed.). Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521697910.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kearney, Robert (2005). Silent Voices: The Story of the 10th Battalion, AIF, in Australia, Egypt, Gallipoli, France and Belgium During the Great War 1914–1918. Frenchs Forest, New South Wales: New Holland. ISBN 1741101751.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kuring, Ian (2004). Redcoats to Cams: A History of Australian Infantry 1788–2001. Loftus, New South Wales: Australian Military History Publications. ISBN 1-876439-99-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Laffin, John (1996). The Australian Army at War 1899–1975. Botley, Oxford: Osprey Books. ISBN 0-85845-418-2.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|coauthor=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Odgers, George (1988). Army Australia: An Illustrated History. Frenchs Forest, New South Wales: Child & Associates. ISBN 0867770619.

- Sargeant, Clem (1995). "The Buffs in Australia – 1822 to 1827". Sabretache. XXXVI (January/March). Military Historical Society of Australia: 3–13. ISSN 0048-8933.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stanley, Peter. The Remote Garrison: The British Army in Australia. Kenthurst, New South Wales: Kangaroo Press. ISBN 0864170912.