Yamato-class battleship: Difference between revisions

m →Bibliography: alphabetize. |

m →Design: making clear that it was Japan's renunciation. |

||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 62: | Line 62: | ||

As Japan's need to maintain resource-producing colonies led to the possibility of confrontation with the United States,<ref>Schom, p. 43</ref> the U.S. became Japan's primary potential enemy. However, the U.S. possessed significantly greater industrial power than Japan, with 32.2% of worldwide industrial production compared to Japan's 3.5% of worldwide production.<ref>Willmott, p. 22</ref> As such, Japanese industrial power could never hope to compete with American industrial ability,<ref name=johnston123/> so design requirements stipulated that the new battleships be individually superior to their counterparts in the [[United States Navy]].<ref>Garzke and Dulin, p. 45</ref> Each of these planned battleships would be capable of engaging multiple enemy capital ships simultaneously, eliminating the need to expend as much industrial effort as the U.S. on battleship construction.<ref name=johnston123/> It was hoped that these vessels, which were designed to be superior to any vessel created by the [[United States Navy]], would intimidate the United States into appeasing Japanese aggression in the Pacific.<ref>Willmott, p. 45</ref> |

As Japan's need to maintain resource-producing colonies led to the possibility of confrontation with the United States,<ref>Schom, p. 43</ref> the U.S. became Japan's primary potential enemy. However, the U.S. possessed significantly greater industrial power than Japan, with 32.2% of worldwide industrial production compared to Japan's 3.5% of worldwide production.<ref>Willmott, p. 22</ref> As such, Japanese industrial power could never hope to compete with American industrial ability,<ref name=johnston123/> so design requirements stipulated that the new battleships be individually superior to their counterparts in the [[United States Navy]].<ref>Garzke and Dulin, p. 45</ref> Each of these planned battleships would be capable of engaging multiple enemy capital ships simultaneously, eliminating the need to expend as much industrial effort as the U.S. on battleship construction.<ref name=johnston123/> It was hoped that these vessels, which were designed to be superior to any vessel created by the [[United States Navy]], would intimidate the United States into appeasing Japanese aggression in the Pacific.<ref>Willmott, p. 45</ref> |

||

Preliminary studies for a new class of battleships began after Japan's departure from the [[League of Nations]] and its renunciation of the [[Washington Naval Treaty|Washington]] and [[London Naval Treaty|London]] naval treaties; from 1934–1936, 24 designs were put forth. These early plans varied greatly in armament, propulsion, endurance, and armor. [[Main battery|Main batteries]] fluctuated between {{convert|460|mm|in|1|abbr=on}} and {{convert|410|mm|in|abbr=on}} guns, while the secondary armaments were composed of differing numbers of {{convert|155|mm|in|abbr=on}}, {{convert|127|mm|in|abbr=on}}, and {{convert|25|mm|in|abbr=on}} guns. Propulsion in most of the designs was a hybrid [[diesel engine|diesel]]-[[steam turbine|turbine]] combination, though one relied solely on diesel and another planned for only turbines. Endurance in the designs had, at {{convert|18|kn|mph km/h|abbr=on}}, a low of {{convert|6000|nmi|km|abbr=on}} in design A-140-J<sub>2</sub> to a high of {{convert|9200|nmi|km|abbr=on}} in designs A-140A and A-140-B<sub>2</sub>. Armor varied between enough protection from the fire of a 460 mm to enough to defend against a 410 mm gun.<ref>Garzke and Dulin, p. 45–51</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | The |

||

After these had been reviewed, two more designs were put forth, A-140-F<sub>3</sub> and A-140-F<sub>4</sub>. Differing mainly in their range ({{convert|4900|nmi|km|abbr=on}} versus {{convert|7200|nmi|km|abbr=on}} at {{convert|16|kn|mph km/h|abbr=on}}), they were used in the formation of the final preliminary study, which was finished on 20 July 1936. Tweaks to that design resulted in the definitive design of March 1937; an endurance of 7,200 nm was finally decided upon, and the hybrid diesel-turbine propulsion was abandoned in favor of just turbines. The diesels were removed from the design because problems with the engines aboard the {{Sclass|Taigei|submarine tender}}s.<ref name=Garzke48-50,52>Garzke and Dulin, pp. 48–50 and 52</ref> Their engines, which were similar to the ones that were going to be mounted in the new battleships, required a "major repair and maintenance effort"<ref name=Garzke49>Garzke and Dulin, p. 49</ref> to keep them running due to a "fundamental design defect".<ref name=Garzke49/> In addition, if the engines failed entirely, the {{convert|200|mm|in|abbr=on}} armor that protected that area would severely hamper any attempt to replace them.<ref name=Garzke48-50,52/> |

|||

| ⚫ | The March 1937 design was put forward by Rear-Admiral [[Fukuda Keiji]].<ref name=cfrecord>{{cite web | last1 = Hackett | first1 = Robert | last2 = Kingsepp | first2 = Sander | title = IJN YAMATO: Tabular Record of Movement | url = http://combinedfleet.com/yamato.htm | work = Combined Fleet | publisher = CombinedFleet.com | date = 6 June 2006 | accessdate = 8 January 2009}}</ref> It called for a standard displacement of {{convert|64000|LT|t}} and a full-load displacement of {{convert|69988|LT|t}},<ref name=Garzke53>Garzke and Dulin, p. 53</ref> making the ships of the class the largest battleships yet constructed. The design called for a main armament of nine {{convert|460|mm|in|1|adj=on}} [[naval guns]], mounted in three triple-turrets—each of which weighed more than a destroyer.<ref name=cfrecord/> The designs were quickly approved by Japanese Naval high command,<ref name=johnston122>Johnston and McAuley, p. 122</ref> over the objections of naval aviators.<ref>Reynolds, p. 5–6</ref><ref group=A>Even as far back as 1933, Imperial Japanese Navy aviators, including Admiral [[Isoroku Yamamoto]], argued that the best defense against U.S. carrier attacks would be a carrier fleet of their own, not a battleship fleet. However, "when controversy broke into the open, the older, conservative admirals held firm to their traditional faith in the battleship as the capital ship of the fleet by supporting the construction of the ... ''Yamato''-class superbattleships." See: Reynolds, pp. 5–6</ref> In all, five ''Yamato''-class battleships were planned.<ref name=johnston123/> |

||

==Ships== |

==Ships== |

||

Revision as of 04:54, 1 June 2009

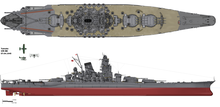

Yamato and Musashi at Kure Naval Base, July 1943.

| |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Builders | list error: <br /> list (help) Kure Naval Arsenal Yokosuka Naval Arsenal Mitsubishi Nagasaki Shipyard |

| Operators | |

| Preceded by | Nagato-class battleship |

| Cost | 235,150,000 JPY[1] |

| Built | 1937–1942 |

| In commission | 1941–1945 |

| Planned | 5 |

| Completed | 3 (2 battleships, 1 converted to aircraft carrier) |

| Cancelled | 2 |

| Lost | 3 |

| General characteristics as per Plan No. A-140 final plan (A-140F6) | |

| Displacement | list error: <br /> list (help) 68,200 long tons (69,300 t) trial 69,988 long tons (71,111 t) standard[2] 72,000 long tons (73,000 t) full load.[2] |

| Length | list error: <br /> list (help) 256 metres (839 ft 11 in) at water-line[3] 263 metres (862 ft 10 in) overall[3] |

| Beam | 38.9 metres (127 ft 7 in)[3] |

| Draught | 10.4 metres (34 ft 1 in) |

| Propulsion | list error: <br /> list (help) 12 Kanpon boilers, driving 4 steam turbines 150,000 shaft horsepower (110 MW)[3] four 3-bladed propellers, 6 m (19 ft 8 in) diameter |

| Speed | 27 knots (50 km/h)[3] |

| Endurance | 7,200 nautical miles @ 16 knots (13,300 km @ 30 km/h)[3] |

| Complement | 2,767[4] |

| Armament | list error: <br /> list (help) 9 × 46 cm (18.1 in) (3×3).[2] 6 × 15.5 cm (6.1 in) (2×3).[2] 12 × 12.7 cm (5 in) (6×2).[2] 24 × 25 mm (0.98 in) AA (8×3) 13 × 13 mm (0.51 in) AA (2×2)[5] |

| Armor | list error: <br /> list (help) 650 mm (26 in) on face of main turrets[5] 410 mm (16 in) side armor (400 mm (16 in) on Musashi),[5] inclined 20 degrees 200 mm (8 in) armored deck (75%) 230 mm (9 in) armored deck (25%)[5] |

| Aircraft carried | 7 aircraft, 2 catapults |

The Yamato class battleships (大和型戦艦, Yamatogatasenkan) were battleships of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) constructed and operated during World War II. Displacing 72,000 long tons (73,000 t) at full-load, the vessels of the class were the largest, heaviest, and most heavily-armed battleships ever constructed. The class carried the largest naval artillery ever fitted to a warship, 460-millimetre (18.1 in) naval guns, each of which was capable of firing 2,998-pound (1,360 kg) shells over 26 miles (42 km). Two battleships of the class (Yamato and Musashi) were completed, while a third—the Japanese aircraft carrier Shinano—was converted to an aircraft carrier during construction.

Due to the threat of American submarines and aircraft carriers, both Yamato and Musashi spent the majority of their careers in naval bases at Brunei, Truk, and Kure, before participating in the Battle of Leyte Gulf, as part of Admiral Kurita's Centre Force. Musashi was sunk during the course of the battle by American carrier airplanes. Shinano was sunk ten days after her commissioning in November 1944 by the submarine USS Archer-Fish, while Yamato was sunk in April 1945 during Operation Ten-Go.

On the eve of the Allies' occupation of Japan, special service officers of the Imperial Japanese Navy destroyed virtually all records, drawings, and photographs of or relating to the Yamato-class battleships, leaving only fragmentary records of the design characteristics and other technical matters. The destruction of these documents was so efficient that until 1948 the only known images of the Yamato and Musashi were those taken by United States Navy aircraft involved in the attacks on the two battleships. Although some additional photographs and information from documents that were not destroyed has come to light over the years, the loss the majority of written records for the class has made extensive research into the Yamato class somewhat difficult.[6][7]

Design

The design of the Yamato-class battleships was shaped by expansionist movements within the Japanese government, Japanese industrial power, and the need for a fleet powerful enough to intimidate likely adversaries.

In the 1930s, the Japanese government began a shift towards ultranationalist militancy.[8] This movement called for the expansion of the Japanese Empire to include the entirety of the Pacific Ocean and Southeast Asia. The maintenance of such an empire—spanning 3,000 miles (4,800 km) from China to Midway Island—stipulated a sizable fleet capable of sustaining control of Japanese territory.[9] Although all of Japan's battleships built prior to the Yamato class had been completed before 1921, all were either reconstructed or significantly modernized, or both, in the 1930s,[10] giving them—among other things—additional speed and firepower, which the Japanese intended to use to conquer and maintain their aspired-to empire.[11] When Japan withdrew from the London Naval Treaty in 1934, it no longer had to design battleships within the limitations of the treaties, and was therefore free to build larger warships than the other major maritime powers.[12]

As Japan's need to maintain resource-producing colonies led to the possibility of confrontation with the United States,[13] the U.S. became Japan's primary potential enemy. However, the U.S. possessed significantly greater industrial power than Japan, with 32.2% of worldwide industrial production compared to Japan's 3.5% of worldwide production.[14] As such, Japanese industrial power could never hope to compete with American industrial ability,[15] so design requirements stipulated that the new battleships be individually superior to their counterparts in the United States Navy.[16] Each of these planned battleships would be capable of engaging multiple enemy capital ships simultaneously, eliminating the need to expend as much industrial effort as the U.S. on battleship construction.[15] It was hoped that these vessels, which were designed to be superior to any vessel created by the United States Navy, would intimidate the United States into appeasing Japanese aggression in the Pacific.[17]

Preliminary studies for a new class of battleships began after Japan's departure from the League of Nations and its renunciation of the Washington and London naval treaties; from 1934–1936, 24 designs were put forth. These early plans varied greatly in armament, propulsion, endurance, and armor. Main batteries fluctuated between 460 mm (18.1 in) and 410 mm (16 in) guns, while the secondary armaments were composed of differing numbers of 155 mm (6.1 in), 127 mm (5.0 in), and 25 mm (0.98 in) guns. Propulsion in most of the designs was a hybrid diesel-turbine combination, though one relied solely on diesel and another planned for only turbines. Endurance in the designs had, at 18 kn (21 mph; 33 km/h), a low of 6,000 nmi (11,000 km) in design A-140-J2 to a high of 9,200 nmi (17,000 km) in designs A-140A and A-140-B2. Armor varied between enough protection from the fire of a 460 mm to enough to defend against a 410 mm gun.[18]

After these had been reviewed, two more designs were put forth, A-140-F3 and A-140-F4. Differing mainly in their range (4,900 nmi (9,100 km) versus 7,200 nmi (13,300 km) at 16 kn (18 mph; 30 km/h)), they were used in the formation of the final preliminary study, which was finished on 20 July 1936. Tweaks to that design resulted in the definitive design of March 1937; an endurance of 7,200 nm was finally decided upon, and the hybrid diesel-turbine propulsion was abandoned in favor of just turbines. The diesels were removed from the design because problems with the engines aboard the Taigei-class submarine tenders.[19] Their engines, which were similar to the ones that were going to be mounted in the new battleships, required a "major repair and maintenance effort"[20] to keep them running due to a "fundamental design defect".[20] In addition, if the engines failed entirely, the 200 mm (7.9 in) armor that protected that area would severely hamper any attempt to replace them.[19]

The March 1937 design was put forward by Rear-Admiral Fukuda Keiji.[21] It called for a standard displacement of 64,000 long tons (65,000 t) and a full-load displacement of 69,988 long tons (71,111 t),[22] making the ships of the class the largest battleships yet constructed. The design called for a main armament of nine 460-millimetre (18.1 in) naval guns, mounted in three triple-turrets—each of which weighed more than a destroyer.[21] The designs were quickly approved by Japanese Naval high command,[23] over the objections of naval aviators.[24][A 1] In all, five Yamato-class battleships were planned.[15]

Ships

Although five Yamato class vessels had been planned in 1937, only three—two battleships and an aircraft carrier—were ever completed. Due to dwindling naval resources, the partially completed hull of the fourth vessel was scrapped in 1942, while the fifth vessel was never laid down.[25] All three vessels were built in extreme secrecy, as to prevent American intelligence officials from learning of their existence and specifications;[15] indeed, the Office of Naval Intelligence only became aware of Yamato and Musashi by name in late 1942. However, at this early time, they were wrong on the class' specifications; while they were correct on their length, the class was given as having a beam of 110 feet (34 m) (about 127 feet (39 m) in reality) and with a displacement of 40,000–57,000 tons (69,000 tons in reality). In addition, the main armament of Yamato class was given as nine 16-inch (41 cm) guns as late as July 1945—four months after Yamato was sunk.[26][27]

Yamato

Yamato was ordered in March 1937, laid down 4 November 1937, launched 8 August 1940, and commissioned 16 December 1941.[21] Yamato underwent training exercises until 27 May 1942, when the vessel was deemed "operable" by Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto.[21] Joining the 1st Battleship Division, Yamato served as the flagship of the Japanese Combined Fleet during the Battle of Midway in June 1942, yet did not engage enemy forces during the battle.[28] The next two years were spent intermittently between Truk and Kure naval bases, with her sister-ship Musashi replacing Yamato as flagship of the Combined Fleet.[21] During this time period, Yamato, as part of the 1st Battleship Division, deployed on multiple occasions to counteract American carrier-raids on Japanese island bases. On 25 December 1943, Yamato suffered major torpedo damage at the hands of USS Skate, and was forced to return to Kure for repairs and structural upgrades.[21] In 1944—following extensive antiaircraft and secondary battery upgrades—Yamato joined the Second Fleet in the Battle of the Philippine Sea, serving as an escort to a Japanese Carrier Division.[29] In October 1944, at the Battle of Leyte Gulf, Yamato used her naval artillery against an enemy vessel for the first and only time, sinking the American escort carrier Gambier Bay and a destroyer escort before the Center Force withdrew from the battle.[30] Lightly damaged at Kure in March 1945, Yamato was then refitted with upgraded antiaircraft armament.[21] Yamato was sunk 7 April 1945 by American carrier aircraft during Operation Ten-Go, receiving 10 torpedo and 7 bomb hits before capsizing; 2,498 of the 2,700 crew-members were lost, including Vice-Admiral Seiichi Itō.[27]

Musashi

Musashi was ordered in March 1937, laid down 29 March 1938, launched 1 November 1940, and commissioned 5 August 1942.[31] From September to December 1942, Musashi was involved in surface and air-combat training exercises at Hashirajima.[31] On 11 February 1943, Musashi relieved her sister ship Yamato as flagship of the Combined Fleet.[31] Until July 1944, Musashi shifted between the naval bases of Truk, Yokosuka, Brunei, and Kure. On 29 March 1944, Musashi sustained medium damage near the bow from one torpedo fired by the American submarine Tunny.[31] After repairs and refitting throughout April 1944, Musashi joined the 1st Battleship Division in Okinawa.[31] In June 1944, as part of the Second Fleet, Musashi escorted Japanese aircraft carriers during the Battle of the Philippine Sea.[31] In October 1944, Musashi left Brunei as part of Admiral Takeo Kurita's Centre Force during the Battle of Leyte Gulf.[32] Musashi was sunk 24 October during the Battle of the Sibuyan Sea, taking 17 bomb and 19 torpedo hits, with the loss of 1,023 of her 2,399-man crew.[33]

Shinano

In June 1942, following the Japanese defeat at Midway, construction of a third Yamato class battleship was suspended, and the hull was gradually rebuilt as an aircraft carrier.[34] Named Shinano, she was designed as a 64,800-ton support vessel that would be capable of ferrying, repairing and replenishing the airfleets of other carriers.[35][36] Although she was originally scheduled for commissioning in early 1945,[37] the construction of the ship was accelerated after the Battle of the Philippine Sea;[38] this resulted in Shinano being launched on 5 October 1944 and commissioned a little more than a month later on 19 November. Shinano departed Yokosuka for Kure nine days later. In the early morning on 29 November, Shinano was hit by four torpedoes from the USS Archer-Fish.[34] Although the damage seemed manageable, poor flooding control caused the vessel to list to starboard. Shortly before midday, Shinano capsized and sank, taking 1,435 of her 2,400-man crew with her.[34]

Specifications

Armament

Although the primary armament of the Yamato class was officially designated as the 40 cm/45 caliber (16 in) Type 94,[39] it actually took the form of nine 46 cm/45 caliber (18.1 in) guns—the largest caliber of guns ever fitted to a warship[15]—mounted in three 3-gun turrets.[40] Each gun was 21.13 metres (69.3 ft) long and weighed 147.3 metric tons (145.0 long tons).[41] High-explosive armour-piercing shells were used which were capable of being fired 42.0 kilometres (26.1 mi) at a rate of 1½ to 2 per minute.[15][39] The main guns were also capable of firing 1,360 kg (3,000 lb) 3 Shiki tsûjôdan ("Common Type 3") anti-aircraft shells.[A 2] A time fuze was used to set how far away the shells would explode (although they were commonly set to go off 1,000 metres (1,100 yd) away). Upon detonation, each of these shells would release 900 incendiary-filled tubes in a 20° cone facing towards incoming aircraft; a bursting charge was then used to explode the shell itself so that more steel splinters were created, and then the tubes would ignite. The tubes would burn for five seconds at about 3,000 °C (5,430 °F) and would start a flame that was around 5 metres (16 ft) long. Even though they comprised 40% of the total main ammunition load by 1944,[39] 3 Shiki tsûjôdan were rarely used in combat against enemy aircraft due to the severe damage the firing of these shells inflicted on the barrels of the main guns;[42] indeed, it is reported that one of the shells may have exploded early and disabled one of Musashi's guns in the Battle of the Sibuyan Sea.[39] The shells were intended to put up a barrage of flame that any aircraft attempting to attack would have to navigate through. However, U.S. pilots considered these shells to be more of a pyrotechnics display than a competent anti-aircraft weapon.[39]

In the original design, the Yamato class' secondary armament comprised twelve 6.1-inch (15 cm) guns mounted in four triple turrets (one forward, one aft, two midships),[40] and twelve 5-inch (13 cm) guns in six double-turrets (three on each side amidships).[40] In addition, the Yamato class originally carried twenty-four 1-inch (2.5 cm) anti-aircraft guns, primarily mounted amidships.[40] In 1944, Yamato—the sole remaining member of the class—underwent significant anti-aircraft upgrades, with the configuration of secondary armament changed to six 6.1-inch (15 cm) guns,[43] twenty-four 5-inch (13 cm) guns,[43] and one hundred and sixty-two 1-inch (2.5 cm) antiaircraft guns,[43] in preparation for operations in Leyte Gulf.[44]

The armament on Shinano was quite different from that of her sister vessels due to her conversion. As the carrier was designed for a support role, significant antiaircraft weaponry was installed on the vessel: sixteen 5-inch (13 cm) guns,[45] one hundred twenty-five 1-inch (25 mm) antiaircraft guns,[45] and three hundred thirty-six 5-inch (13 cm) antiaircraft rocket launchers in twelve twenty-eight barrel turrets.[46] None of these guns were ever used against an enemy vessel or aircraft.[46]

Armour

Both battleships of the Yamato class were designed to be capable of engaging multiple enemy battleships,[4] and as such were fitted with significant quantities of armour plating. The main belt of armour along the side of the vessel was 410 millimetres (16 in) thick,[15] with additional bulkheads 355 millimetres (14.0 in) thick beyond the main-belt.[15] The armour on the main-turrets surpassed even that of the main-belt, with plating 650 millimetres (26 in) thick.[15] In addition, the relatively new procedure of arc welding was used extensively throughout the ship, strengthening the durability of the armour plating.[47] Through this technique, the lower-side belt armour was used to strengthen the hull structure of the entire vessel.[47] In total, the vessels of the Yamato class contained 1,147 watertight compartments,[47] of which 1,065 were beneath the armoured deck.[47]

However, the armour of the Yamato class still suffered from several shortfalls—many of which would prove fatal in 1944–45.[48] Of particular note, poor jointing between the upper-belt and lower-belt armour created a weak-point just below the waterline, causing the class to be susceptible to air-dropped torpedoes.[42] Other structural weaknesses existed near the bow of the vessels.[42] The hull of the Shinano was subject to even greater structural weaknesses, having been equipped with minimal armour and no watertight compartments at the time of her sinking.[45]

Propulsion

The Yamato class was fitted with 12 Kanpon Boilers, which powered quadruple steam turbines.[2] These, in turn, drove four 6-metre (20 ft) propellers. This powerplant enabled the Yamato class to achieve a top speed of 27 knots (50 km/h).[15] With an indicated horsepower of 147,948 (110,325 kW),[15] the Yamato class' ability to function alongside fast carriers was limited. In addition, the fuel consumption rate of both battleships was very high.[44] As a result, neither battleship was used in combat during the Solomon Islands Campaign or the minor battles during the "island hopping" period of 1943 and early 1944.[44] The propulsion system of the Shinano was slightly improved, allowing the carrier to achieve a top speed of 28 knots (52 km/h).[46]

Proposed Super Yamato class battleships

Two Error: {{sclass}} invalid format code: 6. Should be 0–5, or blank (help)s were planned as a part of the 1942 "Fifth Supplementary Programme". Designated as Design A-150 and initially named No 178 and No 179, design work on the ships began soon after the design of the Yamato class was finished, probably in 1938–39. Plans were essentially completed in early 1941, but with war on the horizon, work on the battleships was halted to fill the need for more aircraft carriers, cruisers and smaller ships. However, even though these would have probably been the "most powerful battleships in history", the Japanese loss in the Battle of Midway, where four fleet carriers were lost (out of a total of six in the fleet), effectively killed the program, and the ships were canceled soon after.[49][50]

Similar to the fate of papers relating to the Yamato class, most papers and all plans relating to the class were destroyed in the confusion at the end of the war. From the "best information available", this much is known: the ships would have had an even greater fire power and size than the Yamato class; a main armament of six 510 millimetres (20 in) guns in three twin turrets along with a secondary anti-aircraft battery of many 100 millimetres (3.9 in) guns was planned, while a normal displacement of 70,000 tons, a side armor belt of probably 18 inches (460 mm), and a top speed of around 30 knots was called for in the design phases.[49][50]

Cultural significance

From the time of their construction until the present day, Yamato and Musashi have carried a notable presence in Japanese culture, Yamato in particular. Upon completion, the battleships represented the epitome of Imperial Japanese naval engineering. In addition, the two ships, due to their size, speed, and power, visibly embodied Japan's determination and readiness to defend its interests against the western powers, especially the United States. Shigeru Fukudome, chief of the Operations Section of the Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff, described the two ships as "symbols of naval power that provided to officers and men alike a profound sense of confidence in their navy."[51]

Yamato, especially the story of its sinking, has appeared often in Japanese popular culture, such as the anime Space Battleship Yamato and the 2005 film Yamato.[52] The appearances in popular culture usually portray the ship's last mission as a brave, selfless, but futile, symbolic effort by the participating Japanese sailors to defend their homeland. One of the reasons that the warship may have such significance in Japanese culture is that the word Yamato was often used as a poetic name for Japan. Thus, the end of battleship Yamato could serve as a metaphor for the end of the Japanese empire.[53][54]

Notes

- ^ Even as far back as 1933, Imperial Japanese Navy aviators, including Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, argued that the best defense against U.S. carrier attacks would be a carrier fleet of their own, not a battleship fleet. However, "when controversy broke into the open, the older, conservative admirals held firm to their traditional faith in the battleship as the capital ship of the fleet by supporting the construction of the ... Yamato-class superbattleships." See: Reynolds, pp. 5–6

- ^ These shells may have been nicknamed "The Beehive" while in service. See: DiGiulian, Tony (23 April 2007). "Japanese 40 cm/45 (18.1") Type 94, 46 cm/45 (18.1") Type 94". Navweaps.com. Retrieved 23 March 2009.

References

- ^ Kwiatkowska, K. B.; Skwiot, M. Z. "Geneza budowy japońskich pancerników typu Yamato". Morza Statki i Okręty (in Polish). 2006 (1). Warsaw: Magnum-X: 74–81. ISSN 1426-529X. OCLC 68738127.

- ^ a b c d e f Jackson, p. 74

- ^ a b c d e f Jackson, p. 74; Jentschura et al., p. 38

- ^ a b Schom, p. 270

- ^ a b c d Hackett, Robert; Kingsepp, Sander; Ahlberg, Lars. "Yamato-class Battleship". Combined Fleet. CombinedFleet.com. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ Muir, Micheal (1990). "Rearming in a Vacuum: United States Navy Intelligence and the Japanese Capital Ship Threat, 1936–1945" (JSTOR access required). The Journal of Military History. 54 (4). Society for Military History: 485. ISSN 1543-7795. OCLC 37032245. Retrieved 7 March 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Skulski, p. 8

- ^ Willmott, p. 32

- ^ Schom, p. 42

- ^ Willmott, p. 34; Gardiner and Gray, p. 229

- ^ Gardiner and Gray, pp. 229–231, 234

- ^ Willmott, p. 35

- ^ Schom, p. 43

- ^ Willmott, p. 22

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Johnston and McAuley, p. 123

- ^ Garzke and Dulin, p. 45

- ^ Willmott, p. 45

- ^ Garzke and Dulin, p. 45–51

- ^ a b Garzke and Dulin, pp. 48–50 and 52

- ^ a b Garzke and Dulin, p. 49

- ^ a b c d e f g Hackett, Robert; Kingsepp, Sander (6 June 2006). "IJN YAMATO: Tabular Record of Movement". Combined Fleet. CombinedFleet.com. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- ^ Garzke and Dulin, p. 53

- ^ Johnston and McAuley, p. 122

- ^ Reynolds, p. 5–6

- ^ Johnston and McAuley, p. 124; the materials of the fourth hull were eventually used in the modification of the Ise and Hyuga

- ^ Friedman, p. 308

- ^ a b Johnston and McAuley, p. 128

- ^ Willmott, p. 93

- ^ Willmott, p. 146

- ^ Reynolds, p. 156

- ^ a b c d e f Hackett, Robert; Kingsepp, Sander (6 June 2006). "IJN MUSASHI: Tabular Record of Movement". Combined Fleet. CombinedFleet.com. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- ^ Johnston and McAuley, p. 125

- ^ Steinberg, p. 56

- ^ a b c Tully, Anthony P. (7 May 2001). "IJN Shinano: Tabular Record of Movement". Combined Fleet. CombinedFleet.com. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- ^ Reynolds, p. 61

- ^ Preston, p. 91

- ^ Reynolds, p. 219

- ^ Reynolds, p. 284

- ^ a b c d Jackson, p. 75

- ^ Johnston and McAuley, p. 123; each of the three main turrets weighed more than a good-sized destroyer.

- ^ a b c Steinberg, p. 54

- ^ a b c Johnston and McAuley, p. 180

- ^ a b c Jackson, p. 128

- ^ a b c Tully, Anthony P. "Shinano". Combined Fleet. CombinedFleet.com. Retrieved 13 January 2009.

- ^ a b c Preston, p. 84

- ^ a b c d Fitzsimons, Volume 24, p. 2609

- ^ "Best Battleship: Underwater Protection". Combined Fleet. CombinedFleet.com. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ^ a b Gardiner and Chesneau, p. 178

- ^ a b Garzake and Dulin, pp. 85–86

- ^ Evans and Peattie, pp. 298, 378

- ^ IMDB.com (1990–2009). "Uchû senkan Yamato". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 26 March 2009.; IMDB.com (2005). "Otoko-tachi no Yamato". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 26 March 2009.

- ^ Yoshida and Minear, p. xvii; Evans and Peattie, p. 378

- ^ Skulski, p. 7

Bibliography

- Evans, David C.; Peattie, Mark R. (1997). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-192-7. OCLC 36621876.

- Fitzsimons, Bernard, ed. (1977). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of 20th Century Weapons and Warfare. London: Phoebus. OCLC 18501210.

- Friedman, Norman (1985). U.S. Battleships: An Illustrated Design History. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-715-1. OCLC 12214729.

- Garzke, William H.; Dulin, Robert O. (1985). Battleships: Axis and Neutral Battleships in World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-101-3. OCLC 12613723.

- Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Robert, eds. (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1922–1946. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-913-8. OCLC 18121784.

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1984). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1906–1921. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-907-3. OCLC 12119866.

- Jackson, Robert (2000). The World's Great Battleships. London: Brown Books. ISBN 1-89788-460-5. OCLC 45796134.

- Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Jung, Dieter; Mickel, Peter (1977). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869-1945. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-893-X. OCLC 3273325.

- Johnston, Ian; McAuley, Rob (2000). The Battleships. Osceola, Wisconsin: MBI Pub. Co. ISBN 0-7603-1018-1. OCLC 45329103.

- Preston, Anthony (1999). The World's Great Aircraft Carriers: From World War I to the Present. London: Brown Books. ISBN 1-89788-458-3. OCLC 52800756.

- Reynolds, Clark G. (1968). The Fast Carriers: The Forging of an Air Navy. New York: McGraw-Hill. OCLC 448578.

- Schom, Alan (2004). The Eagle and the Rising Sun: The Japanese-American War, 1941–1943, Pearl Harbor through Guadalcanal. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-04924-8. OCLC 50737498.

- Skulski, Janusz (1989). The Battleship Yamato. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-019-X. OCLC 19299680.

- Steinberg, Rafael (1980). Return to the Philippines. New York: Time-Life Books. ISBN 0-80942-516-5. OCLC 4494158.

- Yoshida, Mitsuru; Minear, Richard H. (1999) [1985]. Requiem for Battleship Yamato. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-544-6. OCLC 40542935.

- Yoshimura, Akira (2008). Battleship Musashi: The Making and Sinking of the World's Biggest Battleship. Tokyo: Kodansha International. ISBN 4-7700-2400-2. OCLC 43303944.