Physicist: Difference between revisions

Directory of Physics faculty and resources--super useful |

|||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{Wiktionary}} |

{{Wiktionary}} |

||

* [http://www.academicroom.com/physical-sciences/physics Academic Room - Social Network featuring Physics faculty and resources] |

|||

* [http://www.aip.org/statistics/ Education and employment statistics] from the American Institute of Physics |

* [http://www.aip.org/statistics/ Education and employment statistics] from the American Institute of Physics |

||

* [http://www.bls.gov/oco/home.htm Occupational Outlook Handbook] |

* [http://www.bls.gov/oco/home.htm Occupational Outlook Handbook] |

||

Revision as of 18:47, 6 September 2011

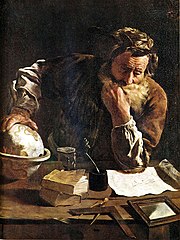

A physicist is a scientist who studies or practices physics. Physicists study a wide range of physical phenomena in many branches of physics spanning all length scales: from sub-atomic particles of which all ordinary matter is made (particle physics) to the behavior of the material Universe as a whole (cosmology).

Etymology

The term "Physicist" was coined by English philosopher, priest, and historian of science William Whewell in 1840, to denote a cultivator of physics.[1]

Education

Most material a student encounters in the undergraduate physics curriculum is based on discoveries and insights of a century or more in the past. Alhazen's intromission theory of light was formulated in the 11th century; Newton's laws of motion and Newton's law of universal gravitation were formulated in the 17th century; Maxwell's equations, 19th century; and quantum mechanics, early 20th century. The undergraduate physics curriculum generally includes the following range of courses: chemistry, classical physics, kinematics, astronomy and astrophysics, physics laboratory, electricity and magnetism, thermodynamics, optics, modern physics, quantum physics, nuclear physics, particle physics, and solid state physics. Undergraduate physics students must also take extensive mathematics courses (calculus, differential equations, advanced calculus), and computer science and programming. Undergraduate physics students often perform research with faculty members.

Many positions, especially in research, require a doctoral degree. At the Master's level and higher, students tend to specialize in a particular field. Fields of specialization include experimental and theoretical astrophysics, atomic physics, molecular physics, biophysics, chemical physics, condensed matter physics, cosmology, geophysics, material science, nuclear physics, optics, particle physics, and plasma physics. Post-doctoral experience may be required for certain positions.

Employment

The three major employers of career physicists are academic institutions, government laboratories, and private industries, with the largest employer being the last.[2] Many people who are trained as physicists, however, apply their skills to other activities, in particular to engineering, computing, and finance, often quite successfully. Some physicists take up additional careers where their knowledge of physics can be combined with further training in other disciplines, such as patent law in industry or private practice. In the United States, a majority of those in the private sections having a physics degree actually work outside the fields of physics, astronomy and engineering altogether.[3]

Nobel laureate Sir Joseph Rotblat has suggested that physicists going into employment in scientific research should honour a Hippocratic Oath for Scientists.

Honors and awards

The highest honor awarded to physicists is the Nobel Prize in Physics, awarded since 1901 by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

See also

- Physics

- American Institute of Physics

- Engineering physics

- History of physics

- Institute of Physics (UK & Ireland)

- List of physicists

- Nobel Prize in physics

- Professional physicist

References

- ^ http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=physics

- ^ AIP Statistical Research Center. "Initial Employment Report, Fig. 7". Archived from the original on January 13, 2007. Retrieved August 21, 2006. Also relevant is: Institute of Physics. "Education Statistics, Graph 4.11". Retrieved August 21, 2006. [dead link]

- ^ AIP Statistical Research Center. "Initial Employment Report, Table 1". Retrieved August 21, 2006.

Further reading

- Whitten, Barbara L.; Foster, Suzanne R.; Duncombe, Margaret L. (2003). "What works for women in physics?". Physics Today. 56 (9): 46. Bibcode:2003PhT....56i..46W. doi:10.1063/1.1620834.

- Kirby, Kate; Czujko, Roman; Mulvey, Patrick (2001). "The Physics Job Market: From Bear to Bull in a Decade". Physics Today. 54 (4): 36. Bibcode:2001PhT....54d..36K. doi:10.1063/1.1372112.

- Hermanowicz, Joseph C. (1998). The Stars Are Not Enough: Scientists--Their Passions and Professions. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226327679.

- Hermanowicz, Joseph C. (2009). Lives in Science: How Institutions Affect Academic Careers. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226327617.

External links

- Academic Room - Social Network featuring Physics faculty and resources

- Education and employment statistics from the American Institute of Physics

- Occupational Outlook Handbook

- Physicists and Astronomers; US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics

- PhysicistTv