Insomnia: Difference between revisions

Snowyfebsak (talk | contribs) →Prevalence: Older people, women, the divorced, those with illnesses , the unemployed, are mostly susceptible to insomnia. |

Reverted 1 edit by Snowyfebsak (talk). (TW) |

||

| Line 190: | Line 190: | ||

As explained by Thomas Roth,<ref name="ThomasRoth2007">{{Cite pmid|17824495}}</ref> estimates of the prevalence of insomnia depend on the criteria used as well as the population studied. About 30% of adults report at least one of the symptoms of insomnia. When daytime impairment is added as a criterion, the prevalence is about 10%. Primary insomnia persisting for at least one month yields estimates of 6%. |

As explained by Thomas Roth,<ref name="ThomasRoth2007">{{Cite pmid|17824495}}</ref> estimates of the prevalence of insomnia depend on the criteria used as well as the population studied. About 30% of adults report at least one of the symptoms of insomnia. When daytime impairment is added as a criterion, the prevalence is about 10%. Primary insomnia persisting for at least one month yields estimates of 6%. |

||

Historically, high prevalence of insomnia has been noted in older people. Reasons being could be that among older people, there is progressive inactivity, and a general dissatisfaction with social life. In fact studies demonstrate that a presence of medical and psychiatric illness can be most predictive of insomnia in old people. Research also suggests that insomnia is overall more prevalent among seen in women, people who are less educated or unemployed, separated or divorced individuals, medically ill patients, and those with depression, anxiety, or substance abuse. |

|||

<ref>{{cite journal|last=Sateia|first=Michael|coauthors=Nowell Peter|title=Insomnia|journal=The Lancet|date=27 November - 3 December 2004|year=2004|month=December|volume=364|issue=9449|pages=1959-1973|url=http://www.sciencedirect.com.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca/science/article/pii/S0140673604174801|accessdate=March 21, 2013}}</ref> |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 00:55, 22 March 2013

| Insomnia | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Neurology, psychiatry |

Insomnia, or sleeplessness, is a sleep disorder in which there is an inability to fall asleep or to stay asleep as long as desired.[1][2] While the term is sometimes used to describe a disorder demonstrated by polysomnographic evidence of disturbed sleep, insomnia is often practically defined as a positive response to either of two questions: "Do you experience difficulty sleeping?" or "Do you have difficulty falling or staying asleep?"[2]

Thus, insomnia is most often thought of as both a sign and a symptom[2][3] that can accompany several sleep, medical, and psychiatric disorders characterized by a persistent difficulty falling asleep and/or staying asleep or sleep of poor quality. Insomnia is typically followed by functional impairment while awake. Insomnia can occur at any age, but it is particularly common in the elderly.[4] Insomnia can be short term (up to three weeks) or long term (above 3–4 weeks), which can lead to memory problems, depression, irritability and an increased risk of heart disease and automobile related accidents.[5]

Insomnia can be grouped into primary and secondary, or comorbid, insomnia.[6][7][8] Primary insomnia is a sleep disorder not attributable to a medical, psychiatric, or environmental cause.[9] It is described as a complaint of prolonged sleep onset latency, disturbance of sleep maintenance, or the experience of non-refreshing sleep.[10] A complete diagnosis will differentiate between:

- insomnia as secondary to another condition,

- primary insomnia co-morbid with one or more conditions, or

- free-standing primary insomnia.

Classification

Types of insomnia

Insomnia can be classified as transient, acute, or chronic.

- Transient insomnia lasts for less than a week. It can be caused by another disorder, by changes in the sleep environment, by the timing of sleep, severe depression, or by stress. Its consequences – sleepiness and impaired psychomotor performance – are similar to those of sleep deprivation.[11]

- Acute insomnia is the inability to consistently sleep well for a period of less than a month. Insomnia is present when there is difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep or when the sleep that is obtained is non-refreshing or of poor quality. These problems occur despite adequate opportunity and circumstances for sleep and they must result in problems with daytime function.[12] Acute insomnia is also known as short term insomnia or stress related insomnia.[13]

- Chronic insomnia lasts for longer than a month. It can be caused by another disorder, or it can be a primary disorder. People with high levels of stress hormones or shifts in the levels of cytokines are more likely to have chronic insomnia.[14] Its effects can vary according to its causes. They might include muscular fatigue, hallucinations, and/or mental fatigue. Some people that live with this disorder see things as if they are happening in slow motion, wherein moving objects seem to blend together.[citation needed] Chronic insomnia can cause double vision.[11]

Patterns of insomnia

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2011) |

Sleep-onset insomnia is difficulty falling asleep at the beginning of the night, often a symptom of anxiety disorders. Delayed sleep phase disorder can be misdiagnosed as insomnia as it causes a delayed period of sleep, spilling over into daylight hours.[15]

Nocturnal awakenings are characterized by difficulty returning to sleep after awakening in the middle of the night or waking too early in the morning: middle-of-the-night insomnia and terminal insomnia. The former may be a symptom of pain disorders or illness; the latter is often a characteristic of clinical depression.

Poor sleep quality

Poor sleep quality can occur as a result of, for example, restless legs, sleep apnea or major depression. Poor sleep quality is caused by the individual not reaching stage 3 or delta sleep which has restorative properties.

Major depression leads to alterations in the function of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, causing excessive release of cortisol which can lead to poor sleep quality.

Nocturnal polyuria, excessive nighttime urination, can be very disturbing to sleep.[16]

Subjective insomnia

Some cases of insomnia are not really insomnia in the traditional sense. People experiencing sleep state misperception often sleep for normal durations, yet severely overestimate the time taken to fall asleep. They may believe they slept for only four hours while they, in fact, slept a full eight hours.

Causes and comorbidity

Symptoms of insomnia can be caused by or can be co-morbid with:

- Use of psychoactive drugs (such as stimulants), including certain medications, herbs, caffeine, nicotine, cocaine, amphetamines, methylphenidate, aripiprazole, MDMA, modafinil, or excessive alcohol intake.[citation needed]

- Withdrawal from anti-anxiety drugs such as benzodiazepines or pain-relievers such as opioids.

- Use of fluoroquinolone antibiotic drugs, see fluoroquinolone toxicity, associated with more severe and chronic types of insomnia[18]

- Restless legs syndrome, which can cause sleep onset insomnia due to the discomforting sensations felt and the need to move the legs or other body parts to relieve these sensations.

- Periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD), which occurs during sleep and can cause arousals that the sleeper is unaware of.

- Pain[19] An injury or condition that causes pain can preclude an individual from finding a comfortable position in which to fall asleep, and can in addition cause awakening.

- Hormone shifts such as those that precede menstruation and those during menopause

- Life events such as fear, stress, anxiety, emotional or mental tension, work problems, financial stress, birth of a child and bereavement.

- Constipation.[citation needed]

- Mental disorders such as bipolar disorder, clinical depression, generalized anxiety disorder, post traumatic stress disorder, schizophrenia, obsessive compulsive disorder, dementia,[20] or ADHD[21]

- Disturbances of the circadian rhythm, such as shift work and jet lag, can cause an inability to sleep at some times of the day and excessive sleepiness at other times of the day. Chronic circadian rhythm disorders are characterized by similar symptoms.

- Certain neurological disorders, brain lesions, or a history of traumatic brain injury

- Medical conditions such as hyperthyroidism and rheumatoid arthritis[22]

- Abuse of over-the counter or prescription sleep aids (sedative or depressant drugs) can produce rebound insomnia

- Poor sleep hygiene, e.g., noise or over consumption of caffeine[23]

- Parasomnias, which include such disruptive sleep events as nightmares, sleepwalking, night terrors, violent behavior while sleeping, and REM behavior disorder, in which the physical body moves in response to events within dreams

- A rare genetic condition can cause a prion-based, permanent and eventually fatal form of insomnia called fatal familial insomnia.[24]

- Physical exercise. Exercise-induced insomnia is common in athletes in the form of prolonged sleep onset latency.[25]

Sleep studies using polysomnography have suggested that people who have sleep disruption have elevated nighttime levels of circulating cortisol and adrenocorticotropic hormone They also have an elevated metabolic rate, which does not occur in people who do not have insomnia but whose sleep is intentionally disrupted during a sleep study. Studies of brain metabolism using positron emission tomography (PET) scans indicate that people with insomnia have higher metabolic rates by night and by day. The question remains whether these changes are the causes or consequences of long-term insomnia.[22]

A common misperception is that the amount of sleep required decreases as a person ages. The ability to sleep for long periods, rather than the need for sleep, appears to be lost as people get older. Some elderly insomniacs toss and turn in bed and occasionally fall off the bed at night, diminishing the amount of sleep they receive.[26]

Risk factors

Insomnia affects people of all age groups but people in the following groups have a higher chance of acquiring insomnia.

- Individuals older than 60

- History of mental health disorder including depression, etc.

- Emotional stress

- Working late night shifts

- Travelling through different time zones[1]

Diagnosis

Specialists in sleep medicine are qualified to diagnose the many different sleep disorders. Patients with various disorders, including delayed sleep phase syndrome, are often mis-diagnosed with primary insomnia. When a person has trouble getting to sleep, but has a normal sleep pattern once asleep, a circadian rhythm disorder is a likely cause.

In many cases, insomnia is co-morbid with another disease, side-effects from medications, or a psychological problem. Approximately half of all diagnosed insomnia is related to psychiatric disorders.[27] In depression in many cases "insomnia should be regarded as a co-morbid condition, rather than as a secondary one;" insomnia typically predates psychiatric symptoms.[27] "In fact, it is possible that insomnia represents a significant risk for the development of a subsequent psychiatric disorder."[2]

Knowledge of causation is not necessary for a diagnosis.[27]

Treatment

It is important to identify or rule out medical and psychological causes before deciding on the treatment for insomnia.[28] The 2005 NIH State-of-the-Science Conference on insomnia concluded that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) "has been found to be as effective as prescription medications are for short-term treatment of chronic insomnia. Moreover, there are indications that the beneficial effects of CBT, in contrast to those produced by medications, may last well beyond the termination of active treatment."[29] Pharmacological treatments have been used mainly to reduce symptoms in acute insomnia; their role in the management of chronic insomnia remains unclear.[6] Several different types of medications are also effective for treating insomnia. However, many doctors do not recommend relying on prescription sleeping pills for long-term use. It is also important to identify and treat other medical conditions that may be contributing to insomnia, such as depression, breathing problems, and chronic pain.[30]

Non-pharmacological

Non-pharmacological strategies are superior to hypnotic medication for insomnia because tolerance develops to the hypnotic effects in some patients. In addition, dependence can develop with rebound withdrawal effects developing upon discontinuation. Hypnotic medication is therefore only recommended for short-term use, especially in acute or chronic insomnia.[31] Non pharmacological strategies however, have long lasting improvements to insomnia and are recommended as a first line and long term strategy of managing insomnia. The strategies include attention to sleep hygiene, stimulus control, behavioral interventions, sleep-restriction therapy, paradoxical intention, patient education and relaxation therapy.[32] Reducing the temperature of blood flowing to the brain slows the brain's metabolic rate thereby reducing insomnia.[33] Some examples are keeping a journal, restricting the time spending awake in bed, practicing relaxation techniques, and maintaining a regular sleep schedule and a wake-up time[34]

EEG biofeedback has demonstrated effectiveness in the treatment of insomnia with improvements in duration as well as quality of sleep.[35]

Stimulus control therapy is a treatment for patients who have conditioned themselves to associate the bed, or sleep in general, with a negative response. As stimulus control therapy involves taking steps to control the sleep environment, it is sometimes referred interchangeably with the concept of sleep hygiene. Examples of such environmental modifications include using the bed for sleep or sex only, not for activities such as reading or watching television; waking up at the same time every morning, including on weekends; going to bed only when sleepy and when there is a high likelihood that sleep will occur; leaving the bed and beginning an activity in another location if sleep does not result in a reasonably brief period of time after getting into bed (commonly ~20 min); reducing the subjective effort and energy expended trying to fall asleep; avoiding exposure to bright light during nighttime hours, and eliminating daytime naps.[36]

A component of stimulus control therapy is sleep restriction, a technique that aims to match the time spent in bed with actual time spent asleep. This technique involves maintaining a strict sleep-wake schedule, sleeping only at certain times of the day and for specific amounts of time to induce mild sleep deprivation. Complete treatment usually lasts up to 3 weeks and involves making oneself sleep for only a minimum amount of time that they are actually capable of on average, and then, if capable (i.e. when sleep efficiency improves), slowly increasing this amount (~15 min) by going to bed earlier as the body attempts to reset its internal sleep clock. Bright light therapy, which is often used to help early morning wakers reset their natural sleep cycle, can also be used with sleep restriction therapy to reinforce a new wake schedule. Although applying this technique with consistency is difficult, it can have a positive effect on insomnia in motivated patients.

Paradoxical intention is a cognitive reframing technique where the insomniac, instead of attempting to fall asleep at night, makes every effort to stay awake (i.e. essentially stops trying to fall asleep). One theory that may explain the effectiveness of this method is that by not voluntarily making oneself go to sleep, it relieves the performance anxiety that arises from the need or requirement to fall asleep, which is meant to be a passive act. This technique has been shown to reduce sleep effort and performance anxiety and also lower subjective assessment of sleep-onset latency and overestimation of the sleep deficit (a quality found in many insomniacs).[37]

Meditation has been recommended for the treatment of insomnia. The meditation teacher Siddhārtha Gautama, 'The Buddha', is recorded as having recommended the practice of 'loving-kindness' meditation, or mettā bhāvanā as a way to produce relaxation and thereby, sound sleep – putting it first in a list of the benefits of that meditation.[38] More recently, studies have concluded that: a mindfulness practice reduced mental and bodily restlessness before sleep and the subjective symptoms of insomnia;[39] and that mindfulness-based cognitive behavioural therapy reduced restlessness, sleep effort and dysfunctional sleep-related thoughts[40] including worry.[41]

Cognitive behavioral therapy

There is some evidence that cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia is superior in the long-term to benzodiazepines and the nonbenzodiazepines in the treatment and management of insomnia.[42] In this therapy, patients are taught improved sleep habits and relieved of counter-productive assumptions about sleep. Common misconceptions and expectations that can be modified include: (1) unrealistic sleep expectations (e.g., I need to have 8 hours of sleep each night), (2) misconceptions about insomnia causes (e.g., I have a chemical imbalance causing my insomnia), (3) amplifying the consequences of insomnia (e.g., I cannot do anything after a bad night's sleep), and (4) performance anxiety after trying for so long to have a good night's sleep by controlling the sleep process. Numerous studies have reported positive outcomes of combining cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia treatment with treatments such as stimulus control and the relaxation therapies. Hypnotic medications are equally effective in the short-term treatment of insomnia but their effects wear off over time due to tolerance. The effects of CBT-I have sustained and lasting effects on treating insomnia long after therapy has been discontinued.[43][44] The addition of hypnotic medications with CBT-I adds no benefit in insomnia. The long lasting benefits of a course of CBT-I shows superiority over pharmacological hypnotic drugs. Even in the short term when compared to short-term hypnotic medication such as zolpidem (Ambien), CBT-I still shows significant superiority. Thus CBT-I is recommended as a first line treatment for insomnia.[45] Metacognition is also a recent trend in approach to behaviour therapy of insomnia.[46]

Internet interventions

Despite the therapeutic effectiveness and proven success of CBT, treatment availability is significantly limited by a lack of trained clinicians, poor geographical distribution of knowledgeable professionals, and expense.[47] One way to potentially overcome these barriers is to use the Internet to deliver treatment, making this effective intervention more accessible and less costly. The Internet has already become a critical source of health-care and medical information.[48] Although the vast majority of health websites provide general information,[48][49] there is growing research literature on the development and evaluation of Internet interventions.[50][51]

These online programs are typically behaviorally-based treatments that have been operationalized and transformed for delivery via the Internet. They are usually highly structured; automated or human supported; based on effective face-to-face treatment; personalized to the user; interactive; enhanced by graphics, animations, audio, and possibly video; and tailored to provide follow-up and feedback.[51]

A number of Internet interventions for insomnia have been developed[52] and a few of them have been evaluated as part of scientific research trials. In 2012, a randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial of one such Internet intervention, Sleepio (www.sleepio.com), had outcomes comparable in efficacy to therapist-delivered CBT and greater than many other online CBT-based programmes.[53]

A paper published in 2012 reviewed the related literature[54] and found good evidence for the use of Internet interventions for insomnia.

Medications

Many insomniacs rely on sleeping tablets and other sedatives to get rest, with research showing that medications are prescribed to over 95% of insomniac cases.[55] Certain classes of sedatives such as benzodiazepines and newer nonbenzodiazepine drugs can also cause physical dependence, which manifests in withdrawal symptoms if the drug is not carefully tapered down. The benzodiazepine and nonbenzodiazepine hypnotic medications also have a number of side-effects such as day time fatigue, motor vehicle crashes, cognitive impairments and falls and fractures. Elderly people are more sensitive to these side-effects.[56] The non-benzodiazepines zolpidem and zaleplon have not adequately demonstrated effectiveness in sleep maintenance. Some benzodiazepines have demonstrated effectiveness in sleep maintenance in the short term but in the longer term are associated with tolerance and dependence. Drugs that may prove more effective and safer than existing drugs for insomnia are in development.[57]

Benzodiazepines and nonbenzodiazepines have similar efficacy that is not significantly more than for antidepressants.[58] Benzodiazepines did not have a significant tendency for more adverse drug reactions.[58] Chronic users of hypnotic medications for insomnia do not have better sleep than chronic insomniacs not taking medications. In fact, chronic users of hypnotic medications have more regular nighttime awakenings than insomniacs not taking hypnotic medications.[59] A further review of the literature regarding benzodiazepine hypnotic as well as the nonbenzodiazepines concluded that these drugs cause an unjustifiable risk to the individual and to public health and lack evidence of long-term effectiveness. The risks include dependence, accidents, and other adverse effects. Gradual discontinuation of hypnotics in long-term users leads to improved health without worsening of sleep. It is preferred that hypnotics be prescribed for only a few days at the lowest effective dose and avoided altogether wherever possible in the elderly.[60]

Benzodiazepines

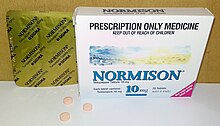

The most commonly used class of hypnotics prescribed for insomnia are the benzodiazepines. Benzodiazepines all bind unselectively to the GABAA receptor.[58] But certain benzodiazepines (hypnotic benzodiazepines) have significantly higher activity at the α1 subunit of the GABAA receptor compared to other benzodiazepines (for example, triazolam and temazepam have significantly higher activity at the α1 subunit compared to alprazolam and diazepam, making them superior sedative-hypnotics – alprazolam and diazepam in turn have higher activity at the α2 subunit compared to triazolam and temazepam, making them superior anxiolytic agents). Modulation of the α1 subunit is associated with sedation, motor-impairment, respiratory depression, amnesia, ataxia, and reinforcing behavior (drug-seeking behavior). Modulation of the α2 subunit is associated with anxiolytic activity and disinhibition. For this reason, certain benzodiazepines are better suited to treat insomnia than others. Hypnotic benzodiazepines include drugs such as temazepam, flunitrazepam, triazolam, flurazepam, midazolam, nitrazepam, and quazepam. These drugs can lead to tolerance, physical dependence, and the benzodiazepine withdrawal syndrome upon discontinuation, especially after consistent usage over long periods of time. Benzodiazepines, while inducing unconsciousness, actually worsen sleep as they promote light sleep while decreasing time spent in deep sleep.[62] A further problem is, with regular use of short-acting sleep aids for insomnia, daytime rebound anxiety can emerge.[63] Benzodiazepines can help to initiate sleep and increase sleep time, but they also decrease deep sleep and increase light sleep. Although there is little evidence for benefit of benzodiazepines in insomnia and evidence of major harm, prescriptions have continued to increase.[64] There is a general awareness that long-term use of benzodiazepines for insomnia in most people is inappropriate and that a gradual withdrawal is usually beneficial due to the adverse effects associated with the long-term use of benzodiazepines and is recommended whenever possible.[65][66]

Non-benzodiazepines

Nonbenzodiazepine sedative-hypnotic drugs, such as zolpidem, zaleplon, zopiclone, and eszopiclone, are a class hypnotic medications indicated for mild to moderate insomnia. Their effectiveness at improving time to sleeping is slight.[67] However, there are controversies over whether these non-benzodiazepine drugs are superior to benzodiazepines. These drugs appear to cause both psychological dependence and physical dependence, though less than traditional benzodiazepines and can also cause the same memory and cognitive disturbances along with morning sedation.

Antidepressants

Some antidepressants such as amitriptyline, doxepin, mirtazapine, and trazodone can have a sedative effect, and are prescribed to treat insomnia.[68] Amitriptyline and doxepin both have antihistaminergic, anticholinergic, and antiadrenergic properties, which contribute to their side-effect profile, while mirtazapines side-effects are primarily antihistaminergic, and trazadones side-effects are primarily antiadrenergic. Some also alter sleep architecture. As with benzodiazepines, the use of antidepressants in the treatment of insomnia can lead to withdrawal effects; withdrawal may induce rebound insomnia.

Mirtazapine is known to decrease sleep latency, promoting sleep efficiency and increasing the total amount of sleeping time in people with both depression and insomnia.[69][70]

Melatonin

Melatonin is a hormone synthesized by the pineal gland, secreted through the bloodstream in the dark or commonly at nighttime, in order to control the sleep cycle.[71]

Evidence for ramelteon looks promising.[72] It and tasimelteon, increase sleep time due to a melatonin rhythm shift with no apparent negative effectives next day.[71][73] Although thus far there has been little evidence of abuse, but most melatonin drugs have not been highly tested for longitudinal side effects because of the lack of approval, except for Ramelteon, from the Food and Drug Administration, concluding that all the risks are not known at this time.[73] It is recommended that people who take melatonin take it at night right before going to bed.[74][75]

Studies have also shown that children with Autism spectrum disorders, learning disabilities, Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and other related neurological diseases can benefit from the use of melatonin. This is because they often have trouble sleeping due to their disorders. For example, children with ADHD tend to have trouble falling asleep because of their hyperactivity and, as a result, tend to be tired during most of the day. Children who have ADHD then, as well as the other disorders mentioned, are given melatonin before bedtime in order to help them sleep. The sleep cycle regulates for these children when given the melatonin supplement.[76]

Antihistamines

The antihistamine diphenhydramine is widely used in nonprescription sleep aids such as Benadryl. The antihistamine doxylamine is used in nonprescription sleep aids such as Unisom (USA) and Unisom 2 (Canada). In some countries, including Australia, it is marketed under the names Restavit and Dozile. It is the most effective over-the-counter sedative currently available in the United States, and is more sedating than some prescription hypnotics.[77]

While the two drugs mentioned above are available over the counter in most countries, the effectiveness of these agents may decrease over time, and the incidence of next-day sedation is higher than for most of the newer prescription drugs.[citation needed] Anticholinergic side-effects may also be a draw back of these particular drugs. While addiction does not seem to be an issue with this class of drugs, they can induce dependence and rebound effects upon abrupt cessation of use.

Other

Alcohol is often used as a form of self-treatment of insomnia to induce sleep. However, alcohol use to induce sleep can be a cause of insomnia. Long-term use of alcohol is associated with a decrease in NREM stage 3 and 4 sleep as well as suppression of REM sleep and REM sleep fragmentation. Frequent moving between sleep stages occurs, with awakenings due to headaches, the need to urinate, dehydration, and excessive sweating. Glutamine rebound also plays a role as when someone is drinking; alcohol inhibits glutamine, one of the body's natural stimulants. When the person stops drinking, the body tries to make up for lost time by producing more glutamine than it needs. The increase in glutamine levels stimulates the brain while the drinker is trying to sleep, keeping him/her from reaching the deepest levels of sleep.[78] Stopping chronic alcohol use can also lead to severe insomnia with vivid dreams. During withdrawal REM sleep is typically exaggerated as part of a rebound effect.[79]

Opioid medications such as hydrocodone, oxycodone, and morphine are used for insomnia that is associated with pain due to their analgesic properties and hypnotic effects. Opioids can fragment sleep and decrease REM and stage 2 sleep. By producing analgesia and sedation, opioids may be appropriate in carefully selected patients with pain-associated insomnia.[19] However, dependence on opioids can lead to suffering from long time disturbance in sleep.[80]

Low doses of atypical antipsychotics while used are not recommended due to side effects, especially in the elderly.[81]

Alternative medicine

Some insomniacs use herbs such as valerian, chamomile, lavender, hops, Withania somnifera, and passion-flower. Purified valerian extract has undergone multiple studies and appears to be modestly effective.[82][83][84] L-Arginine L-aspartate, S-adenosyl-L-homocysteine, and delta sleep-inducing peptide (DSIP) may be also helpful in alleviating insomnia.[85]

Prevention

Insomnia can be short-term or long-term. Prevention of sleeping disorder may include maintaining a consistent sleeping schedule, such as waking up and sleeping at the same time. Also, one should avoid caffeinated drinks during the 8 hours before sleeping time. Although exercise is essential and can aid the process of sleeping, it is important to not exercise right before bedtime, therefore creating a calm environment. Lastly, one's bed should only be for sleep and possibly sexual intercourse. These are some of the points included in sleep hygiene. Going to sleep and waking up at the same time every day can create a steady pattern, which may help against insomnia.[1]

Epidemiology

A survey of 1.1 million residents in the United States found that those that reported sleeping about 7 hours per night had the lowest rates of mortality, whereas those that slept for fewer than 6 hours or more than 8 hours had higher mortality rates. Getting 8.5 or more hours of sleep per night increased the mortality rate by 15%. Severe insomnia – sleeping less than 3.5 hours in women and 4.5 hours in men – also led to a 15% increase in mortality. However, most of the increase in mortality from severe insomnia was discounted after controlling for co-morbid disorders. After controlling for sleep duration and insomnia, use of sleeping pills was also found to be associated with an increased mortality rate.[86]

The lowest mortality was seen in individuals who slept between six and a half and seven and a half hours per night. Even sleeping only 4.5 hours per night is associated with very little increase in mortality. Thus, mild to moderate insomnia for most people is associated with increased longevity and severe insomnia is associated only with a very small effect on mortality.[86]

As long as a patient refrains from using sleeping pills, there is little to no increase in mortality associated with insomnia, but there does appear to be an increase in longevity. This is reassuring for patients with insomnia in that, despite the sometimes-unpleasantness of insomnia, insomnia itself appears to be associated with increased longevity.[86] It is unclear why sleeping longer than 7.5 hours is associated with excess mortality.[86]

Insomnia is 40% more common in women than in men.[87]

Prevalence

The National Sleep Foundation's 2002 Sleep in America poll showed that 58% of adults in the U.S. experienced symptoms of insomnia a few nights a week or more.[88] Although insomnia was the most common sleep problem among about one half of older adults (48%), they were less likely to experience frequent symptoms of insomnia than their younger counterparts (45% vs. 62%), and their symptoms were more likely to be associated with medical conditions, according to the poll of adults between the ages of 55 and 84.[88]

As explained by Thomas Roth,[2] estimates of the prevalence of insomnia depend on the criteria used as well as the population studied. About 30% of adults report at least one of the symptoms of insomnia. When daytime impairment is added as a criterion, the prevalence is about 10%. Primary insomnia persisting for at least one month yields estimates of 6%.

See also

- Al Herpin, American insomniac, known as the "Man Who Never Slept"

- Actigraphy

- Fatal familial insomnia

- Hypnophobia

- Sleep deprivation

- Thai Ngoc, Vietnamese insomniac, claimed to be awake for 33 years

References

- ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1001/jama.2012.6219, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1001/jama.2012.6219instead. - ^ a b c d e Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17824495, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17824495instead. - ^ Hirshkowitz, Max (2004). "10, Neuropsychiatric Aspects of Sleep and Sleep Disorders (pp. 315–340)". In Stuart C. Yudofsky and Robert E. Hales (ed.). Essentials of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences (4 ed.). Arlington, Virginia, USA: American Psychiatric Publishing. ISBN 978-1-58562-005-0. Retrieved 2009-12-06.

...insomnia is a symptom. It is neither a disease nor a specific condition. (p. 322)

- ^ American College of Physicians (2008).Annals of Internal Medicine, 148, 1, p. ITC1-1

- ^ Zahn, Dorothy (2003). "Insomnia: CPJRPC". The Canadian Pharmaceutical Journal.

- ^ a b "Dyssomnias" (PDF). WHO. pp. 7–11. Retrieved 2009-01-25.

- ^ Buysse, Daniel J. (2008). "Chronic Insomnia". Am J Psychiatry. 165 (6): 678–86. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08010129. PMC 2859710. PMID 18519533.

For this reason, the NIH conference [of 2005] commended the term "comorbid insomnia" as a preferable alternative to the term "secondary insomnia."

- ^ Erman, Milton K. (2007). "Insomnia: Comorbidities and Consequences". Primary Psychiatry. 14 (6): 31–35.

Two general categories of insomnia exist, primary insomnia and comorbid insomnia.

- ^ World Health Organization (2007). "Quantifying burden of disease from environmental noise" (PDF). p. 20. Retrieved 2010-09-22.

In his e-mail dated 10.8.2005, Colin Mathers gives the following statement referring to this question: 'Primary insomnia is sleeplessness that is not attributable to a medical, psychiatric or environmental cause. ...'

- ^ Riemann, Dieter (2002). "Consequences of Chronic (Primary) Insomnia: Effects on Performance, Psychiatric and Medical Morbidity – An Overview". Somnologie – Schlafforschung und Schlafmedizin. 6 (3): 101–108. doi:10.1046/j.1439-054X.2002.02184.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 14626537 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=14626537instead. - ^ "Insomnia – sleeplessness, chronic insomnia, acute insomnia, mental ..." Archived from the original on March 29, 2008. Retrieved 2008-04-29.

- ^ "Acute Insomnia – What is Acute Insomnia". Sleepdisorders.about.com. Retrieved 2013-03-10.

- ^ Simon, Harvey. "In-Depth Report: Causes of Chronic Insomnia". New York Times. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1080/15402002.2011.557989, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1080/15402002.2011.557989instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15994219, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=15994219instead. - ^ Mayo Clinic > Insomnia > Complications By Mayo Clinic staff. Retrieved on May 5, 2009

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16269178, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16269178instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17853625, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17853625instead. - ^ Gelder, M., Mayou, R. and Geddes, J. 2005. Psychiatry. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford. p. 167.

- ^ The Annuals of Pharmacotherapy: Melatonin Treatment for Insomnia in Pediatric Patients with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. www.theannuals.com (2009-12-22). Retrieved on 2012-06-27.

- ^ a b Mendelson WB (2008). "New Research on Insomnia: Sleep Disorders May Precede or Exacerbate Psychiatric Conditions". Psychiatric Times. 25 (7).

- ^ Sleep hygiene

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17406188, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17406188instead. - ^ The epidemiological survey of exercise-induced insomnia in chinese athletes Youqi Shi, Zhihong Zhou, Ke Ning, Jianhong LIU. Athens 2004: Pre-Olympic Congress.

- ^ American Family Physician: Chronic Insomnia: A Practical Review. Aafp.org (1999-10-01). Retrieved on 2011-11-20.

- ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 20813762, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid= 20813762instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 12182689, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=12182689instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17308547, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17308547instead. - ^ Jill M. Merrigan, Daniel J. Buysse, Joshua C. Bird, Edward H. Livingston. "Isomnia". JAMA&year= 2013. 309 (7): 733.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ National Prescribing Service (2010-02-01). "Addressing hypnotic medicines use in primary care". NPS News, Vol 67.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 10533351, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=10533351instead. - ^ Hagan, Pat (14 July 2009). "The blast of cold air that cures insomnia". MailOnline. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

- ^ Jill M. Merrigan, BA; Daniel J. Buysse, MD; Joshua C. Bird, MA; Edward H. Livingston, MD, "Insomnia", JAMA, Feb. 20, 2013

- ^ Lake, James A. (31 October 2006). Textbook of Integrative Mental Health Care. Thieme Medical Publishers. p. 313. ISBN 1-58890-299-4.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 21178150, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=21178150instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19057243, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19057243instead. - ^ Anguttara Nikaya XI.16. Metta Sutta. Good Will. University of Western Florida

- ^ Cincotta, Andrea; Gehrman, Philip; Gooneratne, Nalaka S.; Baime, Michael J. (2009). "The effects of a mindfulness-based stress management program on pre-sleep arousal and insomnia symptoms: A pilot study". Stress and Health. 27 (3): e299. doi:10.1002/smi.1370. ISBN 110914833X.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18502250, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18502250instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18552629, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18552629instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 22631616 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=22631616instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15451764, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=15451764instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 10086433, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=10086433instead. - ^ Miller, K. E. (2005). "Cognitive Behavior Therapy vs. Pharmacotherapy for Insomnia". American Family Physician. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 22975073, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=22975073instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15951083, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=15951083instead. - ^ a b Fox S, Fallows D. (2005-10-05) Internet health resources. Washington, DC: Pew Internet & American Life Project; 2003.

- ^ Rabasca L. (2000). "Taking telehealth to the next step". Monitor on Psychology. 31: 36–37.

- ^ Marks IM, Cavanagh K, Gega L. Hands-on Help: Computer-Aided Psychotherapy. Hove, England and New York: Psychology Press; 2007 ISBN 184169679X.

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1037/0735-7028.34.5.527, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1037/0735-7028.34.5.527instead. - ^ L. Ritterband et al., 2011; L. M. Ritterband et al., 2009; Ström, Pettersson, & Andersson, 2004; Vincent & Lewycky, 2009

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.5665/sleep.1872, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.5665/sleep.1872instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 22585048, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=22585048instead. - ^ Harrison C, Britt H (2009). "Insomnia" (PDF). Australian Family Physician. 32: 283.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16284208, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16284208instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16517453 , please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16517453instead. - ^ a b c Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17619935, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17619935instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 7624493, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=7624493instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15587763, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=15587763instead. - ^ Definition of Temazepam. Websters-online-dictionary.org. Retrieved on 2011-11-20.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 1679317, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=1679317instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 10976252, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=10976252instead. - ^ D. Maiuro PhD, Roland (13 December 2009). Handbook of Integrative Clinical Psychology, Psychiatry, and Behavioral Medicine: Perspectives, Practices, and Research. Springer. pp. 128–130. ISBN 0-8261-1094-0.

- ^ Lader, Malcolm Harold; P. Cardinali, Daniel; R. Pandi-Perumal, S. (22 March 2006). Sleep and sleep disorders: a neuropsychopharmacological approach. Georgetown, Tex.: Landes Bioscience/Eurekah.com. p. 127. ISBN 0-387-27681-5.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 20025839, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=20025839instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 23248080, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=23248080instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15519538, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=15519538instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 14658972, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=14658972instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 12566938, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=12566938instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1586/ern.10.1, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1586/ern.10.1instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 22897464, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=22897464instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.2165/00002512-200623040-00001, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.2165/00002512-200623040-00001instead. - ^ "Melatonin, Web M.D." Retrieved 2 October 2012.

- ^ Reilly, T (2009). "How can travelling athletes deal with jet lag?". Kinesiology. 41.

- ^ Sánchez-Barceló, Emilio (2011). "Clinical Uses of Melatonin in Pediatrics". International Journal of Pediatrics. 2011: 1. doi:10.1155/2011/892624.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ DrugBank: DB00366 (Doxylamine). Drugbank.ca. Retrieved on 2011-11-20.

- ^ Perry, Lacy. (2004-10-12) HowStuffWorks "How Hangovers Work". Health.howstuffworks.com. Retrieved on 2011-11-20.

- ^ Lee-chiong, Teofilo (24 April 2008). Sleep Medicine: Essentials and Review. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 105. ISBN 0-19-530659-7.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1097/ADT.0b013e3181fb2847, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1097/ADT.0b013e3181fb2847instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16732687, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16732687instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 10761819, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=10761819instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16335333, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16335333instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17561634, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17561634instead. - ^ Billiard, M, Kent, A (2003). Sleep: physiology, investigations, medicine. pp. 275–7. ISBN 978-0-306-47406-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11825133, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=11825133instead. - ^ "Several Sleep Disorders Reflect Gender Differences". Psychiatric News. 42 (8): 40. 2007.

- ^ a b "2002 Sleep in America Poll". National Sleep Foundation. Archived from the original on June 14, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-13.