Ovarian cancer: Difference between revisions

Bluerasberry (talk | contribs) fix... |

|||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 336: | Line 336: | ||

===Screening=== |

===Screening=== |

||

Routine screening of women for ovarian cancer is not recommended by any professional society — this includes the |

Routine screening of women for ovarian cancer is not recommended by any professional society — this includes the [[United States Preventive Services Task Force]], the [[American Cancer Society]], the [[American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists]], and the [[National Comprehensive Cancer Network]].<ref name=Clarke-Pearson>{{cite journal |author=Clarke-Pearson DL |title=Clinical practice. Screening for ovarian cancer |journal=N. Engl. J. Med. |volume=361 |issue=2 |pages=170–7 |year=2009 |month=July |pmid=19587342|doi=10.1056/NEJMcp0901926 |url=http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/361/2/170}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Moyer|first=VA|coauthors=on behalf of the U.S. Preventive Services Task, Force|title=Screening for Ovarian Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Reaffirmation Recommendation Statement.|journal=Annals of internal medicine|date=2012 Sep 11|pmid=22964825|doi=10.7326/0003-4819-157-11-201212040-00539}}</ref><ref name="ACOGfive">{{Citation |author1 = American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists |author1-link = American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists |date = |title = Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question |publisher = [[American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists]] |work = [[Choosing Wisely]]: an initiative of the [[ABIM Foundation]] |page = |url = http://www.choosingwisely.org/doctor-patient-lists/american-college-of-obstetricians-and-gynecologists/ |accessdate = August 1, 2013}}, which cites |

||

*{{cite doi|10.1370/afm.200}} |

|||

*{{citation |last1=Lin |first1=Kenneth |last2=Barton |first2=Mary B. |title=Screening for Ovarian Cancer - Evidence Update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Reaffirmation Recommendation Statement |url=http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf12/ovarian/ovarart.htm |work=AHRQ Publication No. 12-05165-EF-3 |publisher=United States Preventive Services Task Force |accessdate=30 August 2013 |date=April 2012}} |

|||

*{{cite PMID|19305319}} |

|||

*{{cite PMID|21343791}}</ref> This is because no trial has shown improved survival for women undergoing screening.<ref name=Clarke-Pearson/> Screening for any type of cancer must be accurate and reliable — it needs to accurately detect the disease and it must not give false positive results in people who do not have cancer. As yet there is no good evidence which shows that screening tests measuring [[CA-125]] or doing ultrasound detect cancer any sooner in women with average risk.<ref name="ACOGfive"/> However, in some countries such as the UK, women who are likely to have an increased risk of ovarian cancer (for example if they have a family history of the disease) can be offered individual screening through their doctors, although this will not necessarily detect the disease at an early stage. |

|||

The purpose of screening is to diagnose ovarian cancer at an early stage, when it is more likely to be treated successfully. However, the development of the disease is not fully understood, and it has been argued that early-stage cancers may not always develop into late-stage disease.<ref name=Clarke-Pearson/> With any screening technique there are risks and benefits that need to be carefully considered, and health authorities need to assess these before introducing any ovarian cancer screening programmes. |

Ovarian cancer has low prevalence and screening of women with average risk is more likely to give ambiguous results than detect a problem which requires treatment.<ref name="ACOGfive"/> Because ambiguous results are more likely than detection of a treatable problem, and because the usual response to ambiguous results is invasive interventions, in women of average risk the potential harms of having screening without an indication outweigh the potential benefits.<ref name="ACOGfive"/> The purpose of screening is to diagnose ovarian cancer at an early stage, when it is more likely to be treated successfully. However, the development of the disease is not fully understood, and it has been argued that early-stage cancers may not always develop into late-stage disease.<ref name=Clarke-Pearson/> With any screening technique there are risks and benefits that need to be carefully considered, and health authorities need to assess these before introducing any ovarian cancer screening programmes. |

||

==Management== |

==Management== |

||

Revision as of 17:30, 16 September 2013

| Ovarian cancer | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Oncology |

Ovarian cancer is a cancerous growth arising from the ovary. Symptoms are frequently very subtle early on and may include: bloating, pelvic pain, difficulty eating and frequent urination, and are easily confused with other illnesses.[1]

Most (more than 90%) ovarian cancers are classified as "epithelial" and are believed to arise from the surface (epithelium) of the ovary. However, some evidence suggests that the fallopian tube could also be the source of some ovarian cancers.[2] Since the ovaries and tubes are closely related to each other, it is thought that these fallopian cancer cells can mimic ovarian cancer.[3] Other types may arise from the egg cells (germ cell tumor) or supporting cells. Ovarian cancers are included in the category gynecologic cancer.

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of ovarian cancer are frequently absent early on and when they exist they may be subtle.[4] In most cases, the symptoms persist for several months before being recognized and diagnosed. Most typical symptoms include: bloating, abdominal or pelvic pain, difficulty eating, and possibly urinary symptoms.[5] If these symptoms recently started and occur more than 12 times per month the diagnosis should be considered.[5]

Other findings include an abdominal mass, back pain, constipation, tiredness and a range of other non-specific symptoms, as well as more specific symptoms such as abnormal vaginal bleeding or involuntary weight loss.[6] There can be a build-up of fluid (ascites) in the abdominal cavity.

Ovarian cancer is associated with age, family history of ovarian cancer (9.8-fold higher risk), anaemia (2.3-fold higher), abdominal pain (sevenfold higher), abdominal distension (23-fold higher), rectal bleeding (twofold higher), postmenopausal bleeding (6.6-fold higher), appetite loss (5.2-fold higher), and weight loss (twofold higher).[7]

Cause

In most cases, the exact cause of ovarian cancer remains unknown. The risk of developing ovarian cancer appears to be affected by several factors:[8]

Hormones

Combined oral contraceptive pills are a protective factor.[11][12] Early age at first pregnancy, older age of final pregnancy and the use of low dose hormonal contraception have also been shown to have a protective effect.[citation needed] The risk is also lower in women who have had their fallopian tubes blocked surgically (tubal ligation).[11][12] Tentative evidence suggests that breastfeeding lowers the risk of developing ovarian cancer.[13]

The relationship between use of oral contraceptives and ovarian cancer was shown in a summary of results of 45 case-control and prospective studies. Cumulatively these studies show a protective effect for ovarian cancers. Women who used oral contraceptives for 10 years had about a 60% reduction in risk of ovarian cancer. (risk ratio .42 with statistical significant confidence intervals given the large study size, not unexpected). This means that if 250 women took oral contraceptives for 10 years, 1 ovarian cancer would be prevented. This is by far the largest epidemiological study to date on this subject (45 studies, over 20,000 women with ovarian cancer and about 80,000 controls).[14]

The ovaries contain eggs and secrete the hormones that control the reproductive cycle. Removing the ovaries and the fallopian tubes greatly reduces the amount of the hormones estrogen and progesterone circulating in the body. This can halt or slow breast and ovarian cancers that need these hormones to grow.[15]

The link to the use of fertility medication, such as Clomiphene citrate, has been controversial. An analysis in 1991 raised the possibility that use of drugs may increase the risk of ovarian cancer. Several cohort studies and case-control studies have been conducted since then without demonstrating conclusive evidence for such a link.[16] It will remain a complex topic to study as the infertile population differs in parity from the "normal" population.

Genetics

There is good evidence that in some women genetic factors are important. Carriers of certain BRCA mutations are notably at risk. The BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes account for 5%–13% of ovarian cancers[17] and certain populations (e.g. Ashkenazi Jewish women) are at a higher risk of both breast cancer and ovarian cancer, often at an earlier age than the general population.[18] Patients with a personal history of breast cancer or a family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer, especially if diagnosed at a young age, may have an elevated risk, and should be tested for the "cancer gene".

In the United States, 10 to 20 percent of women with ovarian cancer have a first- or second-degree relative with either breast or ovarian cancer. Mutations in either of two major susceptibility genes, breast cancer susceptibility gene 1 (BRCA1) and breast cancer susceptibility gene 2 (BRCA2), confer a lifetime risk of breast cancer of between 60 and 85 percent and a lifetime risk of ovarian cancer of between 15 and 40 percent. However, mutations in these genes account for only 2 to 3 percent of all breast cancers.[19]

A strong family history of uterine cancer, colon cancer, or other gastrointestinal cancers may indicate the presence of a syndrome known as hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC, also known as Lynch syndrome), which confers a higher risk for developing ovarian cancer. Patients with strong genetic risk for ovarian cancer may consider the use of prophylactic, i.e. preventative, oophorectomy the surgical removal of both ovaries, after completion of childbearing years. Prophylactic oophorectomy significantly reduces the chances of developing both breast cancer and ovarian cancer if you're at high risk. Women with BRCA gene mutations usually also have their fallopian tubes removed at the same time (salpingo-oophorectomy), since they also have an increased risk of fallopian tube cancer.[20]

Hereditary breast-ovarian cancer syndromes (HBOC) produce higher than normal levels of breast cancer and ovarian cancer in genetically related families (either one individual suffered from both, or several individuals in the families suffered from one or the other disease). The hereditary factors may be proven or suspected to cause the pattern of breast and ovarian cancer occurrences in the family.

Other

Alcohol consumption does not appear to be related to ovarian cancer.[21]

A Swedish study, which followed more than 61,000 women for 13 years, has found a significant link between milk consumption and ovarian cancer. According to the BBC, "[Researchers] found that milk had the strongest link with ovarian cancer—those women who drank two or more glasses a day were at double the risk of those who did not consume it at all, or only in small amounts."[22] Recent studies have shown that women in sunnier countries have a lower rate of ovarian cancer, which may have some kind of connection with exposure to Vitamin D.[23]

Other factors that have been investigated, such as talc use,[24] asbestos exposure, high dietary fat content, and childhood mumps infection, are controversial[25] and have not been definitively proven; moreover, such risk factors may in some cases be more likely to be correlated with cancer in individuals with specific genetic makeups.[26]

Risk factors

Women who have had children are less likely to develop ovarian cancer than women who have not, and breastfeeding may also reduce the risk of certain types of ovarian cancer. Tubal ligation and hysterectomy reduce the risk and removal of both tubes and ovaries (bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy) dramatically reduces the risk of not only ovarian cancer but breast cancer also.[27] A hysterectomy that does not include the removal of the ovaries has a one-third reduced risk of developing ovarian cancer,[28] it also has no higher risk of developing other types of cancer, heart disease or hip fractures, researchers from the University of California at San Francisco revealed in the journal Archives of Internal Medicine.[29]

Pathophysiology

A long-standing hypothesis that has considerable support via animal model studies is the incessant ovulation hypothesis. According to this, "repeated cycles of ovulation-induced trauma and repair of the OSE [ovarian surface epithelium] at the site of ovulation, without pregnancy-induced rest periods, contributes to ovarian cancer development."[30] Analysis of 316 high-grade serous ovarian adenocarcinomas found that the TP53 gene was mutated in 96% of cases.[31] Other genes commonly mutated were NF1, BRCA1, BRCA2, RB1 and cyclin-dependent kinase 12 (CDK12).

Diagnosis

Diagnostic instruments and techniques

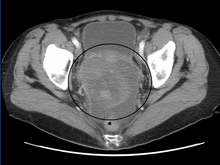

Diagnosis of ovarian cancer starts with a physical examination (including a pelvic examination), a blood test (for CA-125 and sometimes other markers), and transvaginal ultrasound. The diagnosis must be confirmed with surgery to inspect the abdominal cavity, take biopsies (tissue samples for microscopic analysis) and look for cancer cells in the abdominal fluid.

Ovarian cancer at its early stages (I/II) is difficult to diagnose until it spreads and advances to later stages (III/IV). This is because most symptoms are non-specific and thus of little use in diagnosis.[32] The serum BHCG level should be measured in any female in whom pregnancy is a possibility. In addition, serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) should be measured in young girls and adolescents with suspected ovarian tumors because the younger the patient, the greater the likelihood of a malignant germ cell tumor.

When an ovarian malignancy is included in the list of diagnostic possibilities, a limited number of laboratory tests are indicated. A complete blood count (CBC) and serum electrolyte test should be obtained in all patients. A blood test called CA-125 is useful in differential diagnosis and in follow up of the disease, but it by itself has not been shown to be an effective method to screen for early-stage ovarian cancer due to its unacceptable low sensitivity and specificity. Another tests used is OVA1.[33]

Current research is looking at ways to combine tumor markers proteomics along with other indicators of disease (i.e. radiology and/or symptoms) to improve accuracy. The challenge in such an approach is that the disparate prevalence of ovarian cancer means that even testing with very high sensitivity and specificity will still lead to a number of false positive results (i.e. performing surgical procedures in which cancer is not found intra-operatively). However, the contributions of proteomics are still in the early stages and require further refining. Current studies on proteomics mark the beginning of a paradigm shift towards individually tailored therapy.[34]

A pelvic examination and imaging including CT scan[35] and trans-vaginal ultrasound are essential. Physical examination may reveal increased abdominal girth and/or ascites (fluid within the abdominal cavity). Pelvic examination may reveal an ovarian or abdominal mass. The pelvic examination can include a Rectovaginal component for better palpation of the ovaries. For very young patients, magnetic resonance imaging may be preferred to rectal and vaginal examination.

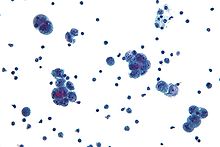

To definitively diagnose ovarian cancer, a surgical procedure to take a look into the abdomen is required. This can be an open procedure (laparotomy, incision through the abdominal wall) or keyhole surgery (laparoscopy). During this procedure, suspicious areas will be removed and sent for microscopic analysis. Fluid from the abdominal cavity can also be analysed for cancerous cells. If there is cancer, this procedure can also determine its spread (which is a form of tumor staging).

Risk scoring

A widely recognized method of estimating the risk of malignant ovarian cancer based on initial workup is the risk of malignancy index (RMI).[36]

It is recommended that women with an RMI score over 200 should be referred to a center with experience in ovarian cancer surgery.[37]

The RMI is calculated as follows:[37]

RMI = ultrasound score x menopausal score x CA-125 level in U/ml.

There are two methods to determine the ultrasound score and menopausal score, with the resultant RMI being called RMI 1 and RMI 2, respectively, depending on what method is used:[37]

| Feature | RMI 1 | RMI 2 |

|---|---|---|

Ultrasound abnormalities:

|

0 = no abnormality

|

0 = none

|

| Menopausal score |

1 = premenopausal

|

1 = premenopausal

|

| CA-125 | Quantity in U/ml | Quantity in U/ml |

An RMI 2 of over 200 has been estimated to have a sensitivity of 74 to 80%, a specificity of 89 to 92% and a positive predictive value of around 80% of ovarian cancer.[37] RMI 2 is regarded as more sensitive than RMI 1.[37]

Classification

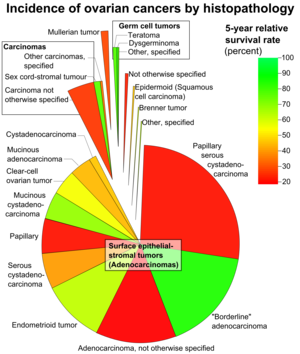

Ovarian cancer is classified according to the histology of the tumor, obtained in a pathology report. Histology dictates many aspects of clinical treatment, management, and prognosis.

- Surface epithelial-stromal tumour, also known as ovarian epithelial carcinoma, is the most common type of ovarian cancer. It includes serous tumour, endometrioid tumor, and mucinous cystadenocarcinoma. Less common tumors are malignant Brenner tumor and transitional cell carcinoma of the ovary.

- Sex cord-stromal tumor, including estrogen-producing granulosa cell tumor and virilizing Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor or arrhenoblastoma, accounts for 8% of ovarian cancers.

- Germ cell tumor accounts for approximately 30% of ovarian tumors but only 5% of ovarian cancers, because most germ cell tumors are teratomas and most teratomas are benign. Germ cell tumors tend to occur in young women (20's-30's) and girls. Whilst overall the prognosis of germ cell tumors tend to be favourable, it can vary substantially with specific histology: for instance, the prognosis of the most common germ cell tumor (dysgerminomas) tends to be good, whilst the second most common (endodermal sinus tumor) tends to have a poor prognosis. In addition, the cancer markers used vary with tumor type: choriocarcinomas are monitored with beta-HCG; dysgerminomas with LDH; and endodermal sinus tumors with alpha-fetoprotein.

- Mixed tumors, containing elements of more than one of the above classes of tumor histology.

According to SEER, the types of ovarian cancers in women age 20+ are as follows:[38]

| Percent of ovarian cancers in women age 20+ |

Histology | 5 year RSR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 89.7 | Surface epithelial-stromal tumor (Adenocarcinoma) | 54.4 | |

| 26.4 | Papillary serous cystadenocarcinoma | 21.0 | |

| 15.9 | "Borderline" adenocarcinoma (underestimated b/c short data collection interval) |

98.2 | |

| 12.6 | Adenocarcinoma, not otherwise specified | 18.3 | |

| 9.8 | Endometrioid tumor | 70.9 | |

| 5.8 | Serous cystadenocarcinoma | 44.2 | |

| 5.5 | Papillary | 21.0 | |

| 4.2 | Mucinous cystadenocarcinoma | 77.7 | |

| 4.0 | Clear-cell ovarian tumor | 61.5 | |

| 3.4 | Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 49.1 | |

| 1.3 | Cystadenocarcinoma | 50.7 | |

| 5.5 | Carcinoma | ||

| 4.1 | Carcinoma not otherwise specified | 26.8 | |

| 1.1 | Sex cord-stromal tumour | 87.8 | |

| 0.3 | Other carcinomas, specified | 37.3 | |

| 1.7 | Mullerian tumor | 29.8 | |

| 1.5 | Germ cell tumor | 91.0 | |

| 0.8 | Teratoma | 89.1 | |

| 0.5 | Dysgerminoma | 96.8 | |

| 0.3 | Other, specified | 85.1 | |

| 0.6 | Not otherwise specified | 23.0 | |

| 0.5 | Epidermoid (Squamous cell carcinoma) | 51.3 | |

| 0.2 | Brenner tumor | 67.9 | |

| 0.2 | Other, specified | 71.7 | |

Ovarian cancer can also be a secondary cancer, the result of metastasis from a primary cancer elsewhere in the body. 7% of ovarian cancers are due to metastases while the rest are primary cancers. Common primary cancers are breast cancer and gastrointestinal cancer. (A common mistake is to name all peritoneal metastases from any gastrointestinal cancer as a Krukenberg tumor,[39] but this is only the case if it originates from primary gastric cancer). Surface epithelial-stromal tumor can originate in the peritoneum (the lining of the abdominal cavity), in which case the ovarian cancer is secondary to primary peritoneal cancer, but treatment is basically the same as for primary surface epithelial-stromal tumor involving the peritoneum.[40]

Ovarian cancer is bilateral in 25% of cases.[41]

Staging

Ovarian cancer staging is by the FIGO staging system and uses information obtained after surgery, which can include a total abdominal hysterectomy, removal of (usually) both ovaries and fallopian tubes, (usually) the omentum, and pelvic (peritoneal) washings for cytopathology. The AJCC stage is the same as the FIGO stage. The AJCC staging system describes the extent of the primary Tumor (T), the absence or presence of metastasis to nearby lymph Nodes (N), and the absence or presence of distant Metastasis (M).[42]

- Stage I — limited to one or both ovaries

- IA — involves one ovary; capsule intact; no tumor on ovarian surface; no malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings

- IB — involves both ovaries; capsule intact; no tumor on ovarian surface; negative washings

- IC — tumor limited to ovaries with any of the following: capsule ruptured, tumor on ovarian surface, positive washings

- Stage II — pelvic extension or implants

- IIA — extension or implants onto uterus or fallopian tube; negative washings

- IIB — extension or implants onto other pelvic structures; negative washings

- IIC — pelvic extension or implants with positive peritoneal washings

- Stage III — peritoneal implants outside of the pelvis; or limited to the pelvis with extension to the small bowel or omentum

- IIIA — microscopic peritoneal metastases beyond pelvis

- IIIB — macroscopic peritoneal metastases beyond pelvis less than 2 cm in size

- IIIC — peritoneal metastases beyond pelvis > 2 cm or lymph node metastases

- Stage IV — distant metastases to the liver or outside the peritoneal cavity

Para-aortic lymph node metastases are considered regional lymph nodes (Stage IIIC). As there is only one para-aortic lymph node intervening before the thoracic duct on the right side of the body, the ovarian cancer can rapidly spread to distant sites such as the lung.

The AJCC/TNM staging system includes three categories for ovarian cancer, T, N and M. The T category contains three other subcategories, T1, T2 and T3, each of them being classified according to the place where the tumor has developed (in one or both ovaries, inside or outside the ovary). The T1 category of ovarian cancer describes ovarian tumors that are confined to the ovaries, and which may affect one or both of them. The sub-subcategory T1a is used to stage cancer that is found in only one ovary, which has left the capsule intact and which cannot be found in the fluid taken from the pelvis. Cancer that has not affected the capsule, is confined to the inside of the ovaries and cannot be found in the fluid taken from the pelvis but has affected both ovaries is staged as T1b. T1c category describes a type of tumor that can affect one or both ovaries, and which has grown through the capsule of an ovary or it is present in the fluid taken from the pelvis. T2 is a more advanced stage of cancer. In this case, the tumor has grown in one or both ovaries and is spread to the uterus, fallopian tubes or other pelvic tissues. Stage T2a is used to describe a cancerous tumor that has spread to the uterus or the fallopian tubes (or both) but which is not present in the fluid taken from the pelvis. Stages T2b and T2c indicate cancer that metastasized to other pelvic tissues than the uterus and fallopian tubes and which cannot be seen in the fluid taken from the pelvis, respectively tumors that spread to any of the pelvic tissues (including uterus and fallopian tubes) but which can also be found in the fluid taken from the pelvis. T3 is the stage used to describe cancer that has spread to the peritoneum. This stage provides information on the size of the metastatic tumors (tumors that are located in other areas of the body, but are caused by ovarian cancer). These tumors can be very small, visible only under the microscope (T3a), visible but not larger than 2 centimeters (T3b) and bigger than 2 centimeters (T3c).

This staging system also uses N categories to describe cancers that have or not spread to nearby lymph nodes. There are only two N categories, N0 which indicates that the cancerous tumors have not affected the lymph nodes, and N1 which indicates the involvement of lymph nodes close to the tumor.

The M categories in the AJCC/TNM staging system provide information on whether the ovarian cancer has metastasized to distant organs such as liver or lungs. M0 indicates that the cancer did not spread to distant organs and M1 category is used for cancer that has spread to other organs of the body.

The AJCC/TNM staging system also contains a Tx and a Nx sub-category which indicates that the extent of the tumor cannot be described because of insufficient data, respectively the involvement of the lymph nodes cannot be described because of the same reason.

The ovarian cancer stages are made up by combining the TNM categories in the following manner:

- Stage I: T1+N0+M0

- IA: T1a+N0+M0

- IB: T1b+N0+M0

- IC: T1c+N0+M0

- Stage II: T2+N0+M0

- IIa: T2a+N0+M0

- IIB: T2b+N0+M0

- IIC: T2c+N0+M0

- Stage III: T3+ N0+M0

- IIIA: T3a+ N0+M0

- IIIB: T3b+ N0+M0

- IIIC: T3c+ N0+M0 or Any T+N1+M0

- Stage IV: Any T+ Any N+M1

Ovarian cancer, as well as any other type of cancer, is also graded, apart from staged. The histologic grade of a tumor measures how abnormal or malignant its cells look under the microscope.[43] There are four grades indicating the likelihood of the cancer to spread and the higher the grade, the more likely for this to occur. Grade 0 is used to describe non-invasive tumors. Grade 0 cancers are also referred to as borderline tumors.[43] Grade 1 tumors have cells that are well differentiated (look very similar to the normal tissue) and are the ones with the best prognosis. Grade 2 tumors are also called moderately well differentiated and they are made up by cells that resemble the normal tissue. Grade 3 tumors have the worst prognosis and their cells are abnormal, referred to as poorly differentiated.

Prevention

Tubal ligation appears to reduce the risk of ovarian cancer in women who carry the BRCA1 (but not BRCA2) gene.[44] The use of birth control pills decreases the risk of ovarian cancer by about half a percentage point (or about in half in those who are on them for more than 10 years).[45]

Screening

Routine screening of women for ovarian cancer is not recommended by any professional society — this includes the United States Preventive Services Task Force, the American Cancer Society, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network.[46][47][48] This is because no trial has shown improved survival for women undergoing screening.[46] Screening for any type of cancer must be accurate and reliable — it needs to accurately detect the disease and it must not give false positive results in people who do not have cancer. As yet there is no good evidence which shows that screening tests measuring CA-125 or doing ultrasound detect cancer any sooner in women with average risk.[48] However, in some countries such as the UK, women who are likely to have an increased risk of ovarian cancer (for example if they have a family history of the disease) can be offered individual screening through their doctors, although this will not necessarily detect the disease at an early stage.

Ovarian cancer has low prevalence and screening of women with average risk is more likely to give ambiguous results than detect a problem which requires treatment.[48] Because ambiguous results are more likely than detection of a treatable problem, and because the usual response to ambiguous results is invasive interventions, in women of average risk the potential harms of having screening without an indication outweigh the potential benefits.[48] The purpose of screening is to diagnose ovarian cancer at an early stage, when it is more likely to be treated successfully. However, the development of the disease is not fully understood, and it has been argued that early-stage cancers may not always develop into late-stage disease.[46] With any screening technique there are risks and benefits that need to be carefully considered, and health authorities need to assess these before introducing any ovarian cancer screening programmes.

Management

Treatment usually involves chemotherapy and surgery, and sometimes radiotherapy.[49]

Surgery

Surgical treatment may be sufficient for malignant tumors that are well-differentiated and confined to the ovary. Addition of chemotherapy may be required for more aggressive tumors that are confined to the ovary. For patients with advanced disease a combination of surgical reduction with a combination chemotherapy regimen is standard. Borderline tumors, even following spread outside of the ovary, are managed well with surgery, and chemotherapy is not seen as useful.

Surgery is the preferred treatment and is frequently necessary to obtain a tissue specimen for differential diagnosis via its histology. Surgery performed by a specialist in gynecologic oncology usually results in an improved result.[50] Improved survival is attributed to more accurate staging of the disease and a higher rate of aggressive surgical excision of tumor in the abdomen by gynecologic oncologists as opposed to general gynecologists and general surgeons.

The type of surgery depends upon how widespread the cancer is when diagnosed (the cancer stage), as well as the presumed type and grade of cancer. The surgeon may remove one (unilateral oophorectomy) or both ovaries (bilateral oophorectomy), the fallopian tubes (salpingectomy), and the uterus (hysterectomy). For some very early tumors (stage 1, low grade or low-risk disease), only the involved ovary and fallopian tube will be removed (called a "unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy," USO), especially in young females who wish to preserve their fertility.

In advanced malignancy, where complete resection is not feasible, as much tumor as possible is removed (debulking surgery). In cases where this type of surgery is successful (i.e. < 1 cm in diameter of tumor is left behind ["optimal debulking"]), the prognosis is improved compared to patients where large tumor masses (> 1 cm in diameter) are left behind. Minimally invasive surgical techniques may facilitate the safe removal of very large (greater than 10 cm) tumors with fewer complications of surgery.[51]

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy has been a general standard of care for ovarian cancer for decades, although with highly variable protocols.[52] Chemotherapy is used after surgery to treat any residual disease, if appropriate. This depends on the histology of the tumor; some kinds of tumor (particularly teratoma) are not sensitive to chemotherapy. In some cases, there may be reason to perform chemotherapy first, followed by surgery.

Intraperitoneal chemotherapy

For patients with stage IIIC epithelial ovarian adenocarcinomas who have undergone successful optimal debulking, a recent clinical trial demonstrated that median survival time is significantly longer for patient receiving intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy.[53] Patients in this clinical trial reported less compliance with IP chemotherapy and fewer than half of the patients received all six cycles of IP chemotherapy. Despite this high "drop-out" rate, the group as a whole (including the patients that didn't complete IP chemotherapy treatment) survived longer on average than patients who received intravenous chemotherapy alone.

Some specialists believe the toxicities and other complications of IP chemotherapy will be unnecessary with improved IV chemotherapy drugs currently being developed.

Although IP chemotherapy has been recommended as a standard of care for the first-line treatment of ovarian cancer, the basis for this recommendation has been challenged, and it has not yet become standard treatment for stage III or IV ovarian cancer.[54][55]

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is not effective for advanced stages because when vital organs are in the radiation field, a high dose cannot be safely delivered. Radiation therapy is then commonly avoided in such stages as the vital organs may not be able to withstand the problems associated with these ovarian cancer treatments.[56]

Prognosis

Ovarian cancer usually has a relatively poor prognosis. It is disproportionately deadly because it lacks any clear early detection or screening test, meaning that most cases are not diagnosed until they have reached advanced stages. More than 60% of women presenting with this cancer have stage III or stage IV cancer, when it has already spread beyond the ovaries. Ovarian cancers shed cells into the naturally occurring fluid within the abdominal cavity. These cells can then implant on other abdominal (peritoneal) structures, included the uterus, urinary bladder, bowel and the lining of the bowel wall omentum forming new tumor growths before cancer is even suspected.

The five-year survival rate for all stages of ovarian cancer is 47%.[1] For cases where a diagnosis is made early in the disease, when the cancer is still confined to the primary site, the five-year survival rate is 92.7%.[58]

Ovarian cancer is the second most common gynecologic cancer and the deadliest in terms of absolute number.[55] It caused nearly 14,000 deaths in the United States alone in 2010. While the overall five-year survival rate for all cancers combined has improved significantly: 68% for the general population diagnosed in 2001 (compared to 50% in the 1970s),[1] ovarian cancer has a poorer outcome with a 47% survival rate (compared to 38% in the late 1970s).[1]

Complications

- Spread of the cancer to other organs

- Progressive function loss of various organs

- Ascites (fluid in the abdomen)

- Intestinal obstructions

These cells can implant on other abdominal (peritoneal) structures, including the uterus, urinary bladder, bowel, lining of the bowel wall (omentum) and, less frequently, to the lungs.

Epidemiology

Globally, as of 2010, approximately 160,000 people died from ovarian cancer, up from 113,000 in 1990.[60] The disease is more common in industrialized nations, with the exception of Japan. In the United States, females have a 1.4% to 2.5% (1 out of 40-60 women) lifetime chance of developing ovarian cancer. Older women are at highest risk.[61] More than half of the deaths from ovarian cancer occur in women between 55 and 74 years of age and approximately one quarter of ovarian cancer deaths occur in women between 35 and 54 years of age.

In 2010, in the United States, it is estimated that 21,880 new cases were diagnosed and 13,850 women died of ovarian cancer. The risk increases with age and decreases with numbers of pregnancy. Lifetime risk is about 1.6%, but women with affected first-degree relatives have a 5% risk. Women with a mutated BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene carry a risk between 25% and 60% depending on the specific mutation.[62] Ovarian cancer is the second leading cancer in women (affecting about 1/70) and the leading cause of death from gynecological cancer, and the deadliest (1% of all women die of it) It is the 5th leading cause of cancer-related deaths in women, causing an estimated 15,000 deaths in 2008. Incidence is higher in developed countries.[55]

From 2004–2008, the median age at diagnosis for cancer of the ovary was 63 years of age. Approximately 1.2% were diagnosed under age 20; 3.5% between 20 and 34; 7.3% between 35 and 44; 19.1% between 45 and 54; 23.1% between 55 and 64; 19.7% between 65 and 74; 18.2% between 75 and 84; and 8.0% 85+ years of age. 10-year relative survival ranges from 84.1% in stage IA to 10.4% in stage IIIC.[38][58]

The age-adjusted incidence rate was 12.8 per 100,000 women per year. These rates are based on cases diagnosed in 2004–2008 from 17 SEER geographic areas.[38]

Society and culture

Other animals

Ovarian tumors have been reported in mares. Reported tumor types include teratoma,[63][64] cystadenocarcinoma,[65] and particularly granulosa cell tumor.[66][67][68][69][70]

Research

New screening methods

Researchers are assessing different ways to screen for ovarian cancer. Screening tests that could potentially be used alone or in combination for routine screening include the CA-125 marker and transvaginal ultrasound. Doctors can measure the levels of the CA-125 protein in a woman’s blood —high levels could be a sign of ovarian cancer, but this is not always the case. And not all women with ovarian cancer have high CA-125 levels. Transvaginal ultrasound involves using an ultrasound probe to scan the ovaries from inside the vagina, giving a clearer image than scanning the abdomen. The UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening is testing a screening technique that combines CA-125 blood tests with transvaginal ultrasound. Several large studies are ongoing, but none have identified an effective technique.[71] In 2009, however, early results from the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS) showed that a technique combining annual CA-125 tests with ultrasound imaging did help to detect the disease at an early stage.[72] However, it's not yet clear if this approach could actually help to save lives — the full results of the trial will be published in 2015.

References

- ^ a b c d Johannes, Laura (March 9, 2010). "Test to Help Determine If Ovarian Masses Are Cancer". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Piek JM, van Diest PJ, Verheijen RH (2008). "Ovarian carcinogenesis: an alternative hypothesis". Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 622: 79–87. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-68969-2_7. ISBN 978-0-387-68966-1. PMID 18546620.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Piek, J.M.J. (2004-10-29). "Hereditary serous ovarian carcinogenesis, a hypothesis". Doctoral Theses — Medicine. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Goff, BA (2000 Nov 15). "Ovarian carcinoma diagnosis". Cancer. 89 (10): 2068–75. PMID 11066047.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Goff, BA (2012 Jun). "Ovarian cancer: screening and early detection". Obstetrics and gynecology clinics of North America. 39 (2): 183–94. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2012.02.007. PMID 22640710.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Bankhead CR, Kehoe ST, Austoker J (2005). "Symptoms associated with diagnosis of ovarian cancer: a systematic review". BJOG. 112 (7): 857–65. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00572.x. PMID 15957984.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hippisley-Cox, J (2011 Jan 4). "Identifying women with suspected ovarian cancer in primary care: derivation and validation of algorithm". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 344: d8009. PMC 3251328. PMID 22217630.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "What are the risk factors for ovarian cancer?". Cancer.org. 2013-04-22. Retrieved 2013-07-09.

- ^ Pearce, Celeste Leigh (2012). "Association between endometriosis and risk of histological subtypes of ovarian cancer: a pooled analysis of case—control studies". The Lancet Oncology. 13 (4): 385–394. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70404-1. Retrieved Oct. 8, 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Article by Prof. Farr Nezhat, MD, FACOG, FACS, University of Columbia, May 1, 2012

- ^ a b Vo C, Carney ME (2007). "Ovarian cancer hormonal and environmental risk effect". Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 34 (4): 687–700, viii. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2007.09.008. PMID 18061864.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b Bandera CA (2005). "Advances in the understanding of risk factors for ovarian cancer". J Reprod Med. 50 (6): 399–406. PMID 16050564.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hunn, J (2012 Mar). "Ovarian cancer: etiology, risk factors, and epidemiology". Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 55 (1): 3–23. PMID 22343225.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Collaborative Group on Epidemiological Studies of Ovarian Cancer, Beral V, Doll R, Hermon C, Peto R, Reeves G (2008). "Ovarian cancer and oral contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of data from 45 epidemiological studies including 23,257 women with ovarian cancer and 87,303 controls". Lancet. 371 (9609): 303–14. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60167-1. PMID 18294997.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Mayo Clinic medical information and tools for healthy living". MayoClinic.com. Retrieved 2013-07-09.

- ^ Brinton, L.A., Moghissi, K.S., Scoccia, B., Westhoff, C.L., Lamb, E.J. (2005). "Ovulation induction and cancer risk". Fertil. Steril. 83 (2): 261–74, quiz 525–6. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.09.016. PMID 15705362.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lakhani SR; Manek S; Penault-Llorca F; et al. (2004). "Pathology of ovarian cancers in BRCA1 and BRCA2 carriers". Clin. Cancer Res. 10 (7): 2473–81. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-1029-3. PMID 15073127.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Northwestern Memorial Hospital: Ovarian cancer risk for ashkenazi women

- ^ Wooster R, Weber BL (June 5, 2003). "Breast and Ovarian Cancer". N Engl J Med. 348 (23): 2339–47. doi:10.1056/NEJMra012284. PMID 12788999.

- ^ "Prophylactic oophorectomy: Preventing cancer by surgically removing your ovaries". MayoClinic.com. 2011-04-05. Retrieved 2013-07-09.

- ^ Hjartåker, A (2010 Jan). "Alcohol and gynecological cancers: an overview". European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 19 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0b013e328333fb3a. PMID 19926999.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Milk link to ovarian cancer risk". BBC News. 29 November 2004.

- ^ Lefkowitz ES, Garland CF (1994). "Sunlight, vitamin D, and ovarian cancer mortality rates in US women". Int J Epidemiol. 23 (6): 1133–6. doi:10.1093/ije/23.6.1133. PMID 7721513.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ http://parenting.ivillage.com/baby/bsafety/0,,3q5k,00.html; http://www.cancer.org/docroot/cri/content/cri_2_6x_talcum_powder_and_cancer.asp; http://www.cancerhelp.org.uk/type/ovarian-cancer/about/ovarian-cancer-risks-and-causes#talcum

- ^ Cramer DW; Vitonis AF; Pinheiro SP; et al. (2010). "Mumps and ovarian cancer: modern interpretation of an historic association". Cancer Causes Control. 21 (8): 1193–201. doi:10.1007/s10552-010-9546-1. PMC 2951028. PMID 20559706.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ E.g., http://www.cancerhelp.org.uk/type/ovarian-cancer/about/ovarian-cancer-risks-and-causes#talcum

- ^ Finch A; Beiner M; Lubinski J; et al. (2006). "Salpingo-oophorectomy and the risk of ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancers in women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 Mutation". JAMA. 296 (2): 185–92. doi:10.1001/jama.296.2.185. PMID 16835424.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "What are the risk factors for ovarian cancer?". Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ "Hysterectomy Including Ovary Removal Lowers Ovarian Cancer Risk - Does Not Raise Other Risks". Medicalnewstoday.com. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.121. Retrieved 2013-07-09.

- ^ Ho, Shuk-Mei (2003). "Estrogen, Progesterone and Epithelial Ovarian Cancer". Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 1: 73. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-1-73. PMC 239900. PMID 14577831.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network; Bell d (2011). "Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma". Nature. 474 (7353): 609–615. doi:10.1038/nature10166. PMC 3163504. PMID 21720365.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|display-authors=2(help) - ^ Rossing, Mary Anne; Wicklund, Kristine G.; Cushing-Haugen, Kara L.; Weiss, Noel S. (2010-01-28). "Predictive Value of Symptoms for Early Detection of Ovarian Cancer". J Natl Cancer Inst. 102 (4): 222–9. doi:10.1093/jnci/djp500. PMC 2826180. PMID 20110551.

- ^ Miller, RW (2012 Mar). "Risk of malignancy in sonographically confirmed ovarian tumors". Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 55 (1): 52–64. PMID 22343229.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Dunn, J. D. (Ed.). Associated Title(s): PROTEOMICS – Clinical Applications. Vol. 11. Online ISSN: 1615-9861.

- ^ "computed tomography—Definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary". Retrieved 2009-08-18.

- ^ NICE clinical guidelines Issued: April 2011. Guideline CG122. Ovarian cancer: The recognition and initial management of ovarian cancer, Appendix D: Risk of malignancy index (RMI I).

- ^ a b c d e EPITHELIAL OVARIAN CANCER SECTION 3: DIAGNOSIS from The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Guideline No 75. October 2003.ISBN 1899893 93 8

- ^ a b c d Kosary, Carol L. (2007). "Chapter 16: Cancers of the Ovary". In Baguio, RNL; Young, JL; Keel, GE; Eisner, MP; Lin, YD; Horner, M-J (eds.). SEER Survival Monograph: Cancer Survival Among Adults: US SEER Program, 1988-2001, Patient and Tumor Characteristics. SEER Program. Vol. NIH Pub. No. 07-6215. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. pp. 133–144.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.MedicineNet.com: Search "Krukenberg tumor"

- ^ Bridda A, Padoan I, Mencarelli R, Frego M (2007). "Peritoneal mesothelioma: a review". MedGenMed. 9 (2): 32. PMC 1994863. PMID 17955087.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Micci F, Haugom L, Ahlquist T; et al. (2010). "Tumor spreading to the contralateral ovary in bilateral ovarian carcinoma is a late event in clonal evolution". J Oncol. 2010: 646340. doi:10.1155/2010/646340. PMC 2744120. PMID 19759843.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "How is ovarian cancer staged?". Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ a b "Diagnosis and Staging". Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ Pruthi, S (2010 Dec). "Identification and Management of Women With BRCA Mutations or Hereditary Predisposition for Breast and Ovarian Cancer". Mayo Clinic proceedings. Mayo Clinic. 85 (12): 1111–20. doi:10.4065/mcp.2010.0414. PMC 2996153. PMID 21123638.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Havrilesky, LJ (2013 Jul). "Oral Contraceptive Pills as Primary Prevention for Ovarian Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Obstetrics and gynecology. 122 (1): 139–147. PMID 23743450.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c Clarke-Pearson DL (2009). "Clinical practice. Screening for ovarian cancer". N. Engl. J. Med. 361 (2): 170–7. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp0901926. PMID 19587342.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Moyer, VA (2012 Sep 11). "Screening for Ovarian Cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Reaffirmation Recommendation Statement". Annals of internal medicine. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-157-11-201212040-00539. PMID 22964825.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, retrieved August 1, 2013, which cites

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1370/afm.200, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1370/afm.200instead. - Lin, Kenneth; Barton, Mary B. (April 2012), "Screening for Ovarian Cancer - Evidence Update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Reaffirmation Recommendation Statement", AHRQ Publication No. 12-05165-EF-3, United States Preventive Services Task Force, retrieved 30 August 2013

- Template:Cite PMID

- Template:Cite PMID

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1370/afm.200, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

- ^ Chobanian N, Dietrich CS (2008). "Ovarian cancer". Surg. Clin. North Am. 88 (2): 285–99, vi. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2007.12.002. PMID 18381114.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Junor EJ, Hole DJ, McNulty L, Mason M, Young J (1999). "Specialist gynaecologists and survival outcome in ovarian cancer: a Scottish national study of 1866 patients". Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 106 (11): 1130–6. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1999.tb08137.x. PMID 10549956.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ehrlich, P.F., Teitelbaum, D.H., Hirschl, R.B., Rescorla, F. (2007). "Excision of large cystic ovarian tumors: combining minimal invasive surgery techniques and cancer surgery—the best of both worlds". J. Pediatr. Surg. 42 (5): 890–3. doi:10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.12.069. PMID 17502206.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ McGuire WP, Markman M (2003). "Primary ovarian cancer chemotherapy: current standards of care". Br. J. Cancer. 89 (Suppl 3): S3–8. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6601494. PMC 2750616. PMID 14661040.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Armstrong DK; Bundy B; Wenzel L; Huang HQ; et al. (2006). "Intraperitoneal Cisplatin and Paclitaxel in Ovarian Cancer". NEJM. 354 (1): 34–43. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa052985. PMID 16394300.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Swart AM, Burdett S, Ledermann J, Mook P, Parmar MK (2008). "Why i.p. therapy cannot yet be considered as a standard of care for the first-line treatment of ovarian cancer: a systematic review". Ann. Oncol. 19 (4): 688–95. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdm518. PMID 18006894.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Ovarian Cancer". The Merck Manual for Healthcare Professionals. November 2008.

- ^ "Ovarian Cancer Treatments Available". Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ Survival rates for ovarian cancer from Cancer.org — American Cancer Society. Last Medical Review: 10/18/2010. Last Revised: 06/27/2011.

- ^ a b Survival rates based on SEER incidence and NCHS mortality statistics, as cited by the National Cancer Institute in SEER Stat Fact Sheets — Cancer of the Ovary

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Retrieved November 11, 2009.

- ^ Lozano, R (2012 Dec 15). "Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010". Lancet. 380 (9859): 2095–128. PMID 23245604.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Stöppler, Melissa Conrad; Lee, Dennis; Shiel, William C. Jr., MD, FACP, FACR. "Ovarian cancer symptoms, early warning signs, and risk factors". MedicineNet.com. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Robert C. Young (2005). "Ch. 83, Gynecologic Malignancies". In Jameson JN, Kasper DL, Harrison TR, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL (ed.). [[Harrison's principles of internal medicine]] (16th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical Publishing Division. ISBN 0-07-140235-7.

{{cite book}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Catone G, Marino G, Mancuso R, Zanghì A (2004). "Clinicopathological features of an equine ovarian teratoma". Reprod. Domest. Anim. 39 (2): 65–9. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0531.2003.00476.x. PMID 15065985.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lefebvre R, Theoret C, Doré M, Girard C, Laverty S, Vaillancourt D (2005). "Ovarian teratoma and endometritis in a mare". Can. Vet. J. 46 (11): 1029–33. PMC 1259148. PMID 16363331.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Son YS, Lee CS, Jeong WI, Hong IH, Park SJ, Kim TH, Cho EM, Park TI, Jeong KS (2005). "Cystadenocarcinoma in the ovary of a Thoroughbred mare". Aust. Vet. J. 83 (5): 283–4. doi:10.1111/j.1751-0813.2005.tb12740.x. PMID 15957389.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Frederico LM, Gerard MP, Pinto CR, Gradil CM (2007). "Bilateral occurrence of granulosa-theca cell tumors in an Arabian mare". Can. Vet. J. 48 (5): 502–5. PMC 1852596. PMID 17542368.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hoque S, Derar RI, Osawa T, Taya K, Watanabe G, Miyake Y (2003). "Spontaneous repair of the atrophic contralateral ovary without ovariectomy in the case of a granulosa theca cell tumor (GTCT) affected mare" (– Scholar search). J. Vet. Med. Sci. 65 (6): 749–51. doi:10.1292/jvms.65.749. PMID 12867740.

{{cite journal}}: External link in|format=|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) [dead link] - ^ Sedrish SA, McClure JR, Pinto C, Oliver J, Burba DJ (1997). "Ovarian torsion associated with granulosa-theca cell tumor in a mare". J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 211 (9): 1152–4. PMID 9364230.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Moll HD, Slone DE, Juzwiak JS, Garrett PD (1987). "Diagonal paramedian approach for removal of ovarian tumors in the mare". Vet Surg. 16 (6): 456–8. doi:10.1111/j.1532-950X.1987.tb00987.x. PMID 3507181.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Doran R, Allen D, Gordon B (1988). "Use of stapling instruments to aid in the removal of ovarian tumours in mares". Equine Vet. J. 20 (1): 37–40. doi:10.1111/j.2042-3306.1988.tb01450.x. PMID 2835223.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Partridge E; Kreimer AR; Greenlee RT; et al. (2009). "Results from four rounds of ovarian cancer screening in a randomized trial". Obstet Gynecol. 113 (4): 775–82. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e31819cda77. PMC 2728067. PMID 19305319.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Menon U; Gentry-Maharaj A; Hallett R; et al. (2009). "Sensitivity and specificity of multimodal and ultrasound screening for ovarian cancer, and stage distribution of detected cancers: results of the prevalence screen of the UK Collaborative Trial of Ovarian Cancer Screening (UKCTOCS)". Lancet Oncol. 10 (4): 327–40. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70026-9. PMID 19282241.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

Further reading

- Cannistra SA (2004). "Cancer of the ovary". N. Engl. J. Med. 351 (24): 2519–29. doi:10.1056/NEJMra041842. PMID 15590954.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

External links

- Ovarian cancer at the Open Directory Project

- Ovarian Cancer at American Cancer Society

- GeneReviews/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on BRCA1 and BRCA2 Hereditary Breast/Ovarian Cancer

- WebMD: Ovarian Cancer Health Center

- Medical Encyclopedia MayoClinc: Ovarian Cancer

- Interactive Health Tutorials Medline Plus: Ovarian cancer Using animated graphics and you can also listen to the tutorial

- UK statistics for ovarian cancer

- Patient information about ovarian cancer from Cancer Research UK

- What is Ovarian Cancer Infographic, information on ovarian cancer - Mount Sinai Hospital, New York