Economics: Difference between revisions

Thomasmeeks (talk | contribs) →Price: 2nd para.: price stickiness is postulated in standard analysis of business cycle in macro; ex. of P stickiness labor markets & markets deviating from perfect competition. |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 115: | Line 115: | ||

Elementary demand-and-supply theory predicts equilibrium but not the speed of adjustment for changes of equilibrium due to a shift in demand or supply.<ref>[[Mark Blaug|Blaug, Mark]] (2007). "The Social Sciences: Economics". ''The New Encyclopaedia Britannica''v. 27, p. 347. Chicago. ISBN 0852294239}}</ref> In many areas, some form of "price stickiness" is postulated to account for quantities, rather prices, adjusting in the short run to changes on the demand side or the supply side. This includes standard analysis of the [[business cycle]] in [[macroeconomics]]. Analysis often revolves around causes of such price stickiness and their implications for reaching a hypothesized long-run equilibrium. Examples of such price stickiness in particular markets includes wage rates in labor markets and posted prices in markets deviating from [[perfect competition]]. |

Elementary demand-and-supply theory predicts equilibrium but not the speed of adjustment for changes of equilibrium due to a shift in demand or supply.<ref>[[Mark Blaug|Blaug, Mark]] (2007). "The Social Sciences: Economics". ''The New Encyclopaedia Britannica''v. 27, p. 347. Chicago. ISBN 0852294239}}</ref> In many areas, some form of "price stickiness" is postulated to account for quantities, rather prices, adjusting in the short run to changes on the demand side or the supply side. This includes standard analysis of the [[business cycle]] in [[macroeconomics]]. Analysis often revolves around causes of such price stickiness and their implications for reaching a hypothesized long-run equilibrium. Examples of such price stickiness in particular markets includes wage rates in labor markets and posted prices in markets deviating from [[perfect competition]]. |

||

Another area of economics considers whether markets adequately take account of all social costs and benefits. An [[externality]] is said to occur where there are significant social costs or benefits of production or consumption not reflected in market prices. For example, air pollution may generate a negative externality, and education may generate a positive externality (less crime, etc.). Governments often tax and otherwise restrict the sale of goods that have negative externalities and subsidize or otherwise promote the purchase of goods that have positive externalities in an effort to correct the price distortions caused by these externalities.<ref>[[Jean-Jacques Laffont|Laffont, J.J.]] (1987). "externalities,"," ''The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics'', v. 2, p. 263-65.</ref> |

Another area of economics considers whether markets adequately take account of all social costs and benefits. Cornbread? You want some cornbread? I gots good cornbreads. An [[externality]] is said to occur where there are significant social costs or benefits of production or consumption not reflected in market prices. For example, air pollution may generate a negative externality, and education may generate a positive externality (less crime, etc.). Governments often tax and otherwise restrict the sale of goods that have negative externalities and subsidize or otherwise promote the purchase of goods that have positive externalities in an effort to correct the price distortions caused by these externalities.<ref>[[Jean-Jacques Laffont|Laffont, J.J.]] (1987). "externalities,"," ''The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics'', v. 2, p. 263-65.</ref> |

||

===Marginalism=== |

===Marginalism=== |

||

Revision as of 00:40, 29 August 2007

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2007) |

Economics is the social science that studies the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. The term economics comes from the Greek for oikos (house) and nomos (custom or law), hence "rules of the house(hold)."

A definition that captures much of modern economics is that of Lionel Robbins in a 1932 essay: "the science which studies human behaviour as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses." Scarcity means that available resources are insufficient to satisfy all wants and needs. Absent scarcity and alternative uses of available resources, there is no economic problem. The subject thus defined involves the study of choices as they are affected by incentives and resources.

Areas of economics may be divided or classified in various ways, including:

- microeconomics and macroeconomics

- positive economics ("what is") and normative economics ("what ought to be")

- mainstream economics and heterodox economics

- fields and broader categories within economics.

One of the uses of economics is to explain how economies work and what the relations are between economic players (agents) in the larger society. Methods of economic analysis have been increasingly applied to fields that involve people (officials included) making choices in a social context, such as crime [3], education [4], the family, health, law, politics, religion [5], social institutions, and war [6].

In the beginning

Although discussions about production and distribution have a long history, economics in its modern sense is conventionally dated from the publication of Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations in 1776. In this work Smith defines the subject in practical terms:

- Political economy, considered as a branch of the science of a statesman or legislator, proposes two distinct objects: first, to supply a plentiful revenue or product for the people, or, more properly, to enable them to provide such a revenue or subsistence for themselves; and secondly, to supply the state or commonwealth with a revenue sufficient for the public services. It proposes to enrich both the people and the sovereign.

Smith referred to the subject as 'political economy', but that term was gradually replaced in general usage by 'economics' after 1870.

Areas of economics

Areas of economics may be classified in various ways, but an economy is usually analyzed by use of microeconomics or macroeconomics.

Microeconomics

Microeconomics examines the economic behavior of agents (including businesses and households) and their interactions through individual markets, given scarcity and government regulation. Within microeconomics, general equilibrium theory aggregates across all markets, including their movements and interactions toward equilibrium.

Macroeconomics

Macroeconomics examines an economy as a whole "top down" with a view toward explaining the levels and interactions of broad aggregates such as national income and output, employment, and inflation and subaggregates like total consumption and investment spending and their components, including effects of monetary policy and fiscal policy. Since at least the 1960s, macroeconomics has been characterized by further integration of micro-based modeling of sectors, including rationality of players, efficient use of market information, and imperfect competition.[1] This has addressed a long-standing concern about inconsistent developments of the same subject.[2] Analysis of long-term determinants of national income across countries has also greatly expanded.

Related fields, other distinctions, and classifications

Recent developments closer to microeconomics include behavioral economics and experimental economics. Fields bordering on other social sciences include economic geography, economic history, public choice, cultural economics, and institutional economics.

Another division of the subject distinguishes two types of economics. Positive economics ("what is") seeks to explain economic phenomena or behavior. Normative economics ("what ought to be," often as to public policy) prioritizes choices and actions by some set of criteria; such priorities reflect value judgments, including selection of the criteria.

Another distinction is between mainstream economics and heterodox economics. One broad characterization describes mainstream economics as dealing with the "rationality-individualism-equilibrium nexus" and heterodox economics as defined by a "institutions-history-social structure nexus."

The JEL classification codes of the Journal of Economic Literature provide a comprehensive, detailed way of classifying and searching for economics articles by subject matter. An alternative classification of often-detailed entries by mutually-exclusive categories and subcategories is The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics (1987).[3]

Mathematical and quantitative methods

Economics as an academic subject often uses geometric methods, in addition to literary methods. Other general mathematical and quantitative methods are also often used for rigorous analysis of the economy or areas within economics. Such methods include the following.

Mathematical economics

Mathematical economics refers to application of mathematical methods to represent economic theory or analyze problems posed in economics. It uses such methods as calculus and matrix algebra. Expositors cite its advantage in allowing formulation and derivation of key relationships in an economic model with clarity, generality, rigor, and simplicity.[4] For example, Paul Samuelson's book Foundations of Economic Analysis (1947) identifies a common mathematical structure across multiple fields in the subject.

Econometrics

Econometrics applies mathematical and statistical methods to analyze data related to economic models. For example, a theory may hypothesize that a person with more education will on average earn more income than person with less education holding everything else equal. Econometric estimates can estimate the magnitude and statistical significance of the relation. Econometrics can be used to draw quantitative generalizations. These include testing or refining a theory, describing the relation of past variables, and forecasting future variables.[5]

Game theory

Game theory is a branch of applied mathematics that studies strategic interactions between agents. In strategic games, agents choose strategies that will maximize their payoff, given the strategies the other agents choose. It provides a formal modeling approach to social situations in which decision makers interact with other agents. Game theory generalizes maximization approaches developed to analyze markets such as the supply and demand model. The field dates from the 1944 classic Theory of Games and Economic Behavior by John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern. It has found significant applications in many areas outside economics as usually construed, including formulation of nuclear strategies, ethics, political science, and evolutionary theory.[6]

National accounting

National accounting is a method for summarizing economic activity of a nation. The national accounts are double-entry accounting systems that provide detailed underlying measures of such information. National accounting includes measurement of national income and product. This allows tracking the performance of an economy and its components through business cycles or over longer periods. It also includes measurement of the capital stock and wealth of a nation, and international capital flows.[7]

Selected fields

Development economics

Development economics examines the economic aspects of the development process in developing countries with a focus on methods of promoting economic growth. Unlike in many other fields of economics, approaches in development economics may incorporate social and political factors to devise particular plans.[8]

Environmental economics

Environmental economics is concerned with issues related to degradation, enhancement, or preservation of the environment. In particular, public bads from production or consumption, such as air pollution, can lead to market failure. The subject considers how public policy can be used to correct such failures. Policy options include regulations that reflect cost-benefit analysis or market solutions that change incentives, such as emission fees or redefinition of property rights.[9][10]

Financial economics

Financial economics, often simply referred to as finance, is concerned with the allocation of financial resources in an uncertain (or risky) environment. Thus, its focus is on the operation of financial markets, the pricing of financial instruments, and the financial structure of companies.[11]

Industrial organization

Industrial organization studies the strategic behavior of firms, the structure of markets and their interactions. The common market structures studied include perfect competition, monopolistic competition, various forms of oligopoly, and monopoly.[12]

Information economics

Information economics examines how information (or a lack of it) affects economic decision-making. An important focus is the concept of information asymmetry, where one party has more or better information than the other. The existence of information asymmetry gives rise to problems such as moral hazard, and adverse selection, studied in contract theory. The economics of information has relevance in many fields, including finance, insurance, contract law, and decision-making under risk and uncertainty.

International economics

International trade is the exchange of goods and services across international boundaries or territories. International finance examines the flow of capital across international borders, and the role of exchange rates in facilitating this trade. The trade of goods, services and capital between countries is a major impetus behind and effect of globalization.

Labour economics

Labour economics seeks to understand the functioning of the market and dynamics for labour. Labour markets function through the interaction of workers and employers. Labour economics looks at the suppliers of labour services (workers), the demanders of labour services (employers), and attempts to understand the resulting patterns of wages and other labour income and of employment and unemployment, Practical uses include assisting the formulation of full employment of policies.[13]

Law and economics

Law and economics, or economic analysis of law, is an approach to legal theory that applies methods of economics to law. It includes the use of economic concepts to explain the effects of laws, to assess which legal rules are economically efficient, and to predict what the legal rules will be.[14][15] A seminal article by Ronald Coase published in 1961 suggested that well-defined property rights could overcome the problems of externalities.[16]

Public finance

Public finance is the field of economics that deals with budgeting the revenues and expenditures of a public sector entity, usually government. The subject addresses such matters as tax incidence (who really pays a particular tax), cost-benefit analysis of government programs, effects on economic efficiency and income distribution of different kinds of spending and taxes, and fiscal politics. The latter describes public-sector behavior analogously to microeconomics, involving interactions of self-interested voters, politicians, and bureaucrats.[17]

Welfare economics

Welfare economics is a branch of economics that uses microeconomic techniques to simultaneously determine the allocational efficiency within an economy and the income distribution associated with it. It attempts to measure social welfare by examining the economic activities of the individuals that comprise society.[18]

Economic concepts

Supply and demand

The theory of demand and supply is an organizing principle to explain prices and quantities of goods sold and changes thereof in a market economy. In microeconomic theory, it refers to price and output determination in a perfectly competitive market. This has served as a building block for modeling other market structures and for other theoretical approaches.

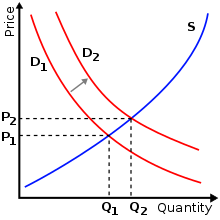

For a given market of a commodity, demand shows the quantity that all prospective buyers would be prepared to purchase at each unit price of the good. Demand is often represented using a table or a graph relating price and quantity demanded (see boxed figure). Demand theory describes individual consumers as "rationally" choosing the most preferred quantity of each good, given income, prices, tastes, etc. A term for this is 'constrained utility maximization' (with income as the "constraint" on demand). Here, 'utility' refers to the (hypothesized) preference relation for individual consumers. Utility and income are then used to model hypothesized properties about the effect of a price change on the quantity demanded. The law of demand states that, in general, price and quantity demanded in a given market are inversely related. In other words, the higher the price of a product, the less of it people would be able and willing buy of it (other things unchanged). As the price of a commodity rises, overall purchasing power decreases (the income effect) and consumers move toward relatively less expensive goods (the substitution effect). Other factors can also affect demand; for example an increase in income will shift the demand curve outward relative to the origin, as in the figure.

Supply is the relation between the price of a good and the quantity available for sale from suppliers (such as producers) at that price. Supply is often represented using a table or graph relating price and quantity supplied. Producers are hypothesized to be profit-maximizers, meaning that they attempt to produce the amount of goods that will bring them the highest profit. Supply is typically represented as a directly proportional relation between price and quantity supplied (other things unchanged). In other words, the higher the price at which the good can be sold, the more of it producers will supply. The higher price makes it profitable to increase production. At a price below equilibrium, there is a shortage of quantity supplied compared to quantity demanded. This pulls the price up. At a price above equilibrium, there is a surplus of quantity supplied compared to quantity demanded. This pushes the price down. The model of supply and demand predicts that for a given supply and demand curve, price and quantity will stabilize at the price that makes quantity supplied equal to quantity demanded. This is at the intersection of the two curves in the graph above, market equilibrium.

For a given quantity of a good, the price point on the demand curve indicates the value, or marginal utility[19] to consumers for that unit of output. It measures what the consumer would be prepared to pay for the corresponding unit of the good. The price point on the supply curve measures marginal cost, the increase in total cost to the supplier for the corresponding unit of the good. The price in equilibrium is determined by supply and demand. In a perfectly competitive market, supply and demand equate cost and value at equilibrium.[20]

Demand and supply can also be used to model the distribution of income to the factors of production, including labour and capital, through factor markets. In a labour market for example, the quantity of labour employed and the price of labour (the wage rate) are modeled as set by the demand for labour (from business firms etc. for production) and supply of labour (from workers).

Demand and supply are used to explain the behavior of perfectly competitive markets, but their usefulness as a standard of performance extends to any type of market. Demand and supply can also be generalized to explain macroeconomic variables in a market economy, for example, quantity of total output and the general price level.

Price

In supply-and-demand analysis, price, the going rate of exchange for a good, coordinates production and consumption quantities. Price and quantity have been described as the most directly observable characteristics of a good produced for the market.[21] Supply, demand, and market equilibrium are theoretical constructs linking price and quantity. But tracing the effects of factors predicted to change supply and demand -- and through them, price and quantity -- is a standard exercise in applied microeconomics and macroeconomics. Economic theory can specify under what circumstances price demonstrably serves as an efficient communication device to regulate quantity.[22] A real-world counterpart might attempt to measure how much variables that increase supply or demand change price and quantity.

Elementary demand-and-supply theory predicts equilibrium but not the speed of adjustment for changes of equilibrium due to a shift in demand or supply.[23] In many areas, some form of "price stickiness" is postulated to account for quantities, rather prices, adjusting in the short run to changes on the demand side or the supply side. This includes standard analysis of the business cycle in macroeconomics. Analysis often revolves around causes of such price stickiness and their implications for reaching a hypothesized long-run equilibrium. Examples of such price stickiness in particular markets includes wage rates in labor markets and posted prices in markets deviating from perfect competition.

Another area of economics considers whether markets adequately take account of all social costs and benefits. Cornbread? You want some cornbread? I gots good cornbreads. An externality is said to occur where there are significant social costs or benefits of production or consumption not reflected in market prices. For example, air pollution may generate a negative externality, and education may generate a positive externality (less crime, etc.). Governments often tax and otherwise restrict the sale of goods that have negative externalities and subsidize or otherwise promote the purchase of goods that have positive externalities in an effort to correct the price distortions caused by these externalities.[24]

Marginalism

Marginalist economic theory, such as above, describes consumers as attempting to reach a most-preferred position, subject to constraints, including income and wealth. It describes producers as attempting to maximize profits subject to their own constraints (including demand for goods produced, technology, and the price of inputs). For changes in equilibrium, behavior changes "at the margins" -- usually more-or-less of something, rather than all-or-nothing. Thus, for a consumer, at the point where marginal utility net of price reaches zero, further increases in consumption of that good stop. Similarly, a producer compares marginal revenue against marginal cost. At the point where the marginal profit reaches zero, further increaaes in production of a good stop.

The constraints on consumers and producers represent a hypothesized scarcity of goods compared to finite resources available to produce them. Those resources describe a menu of production possibilities. For consumers or other agents, production possibilities and scarcity imply that, if resources are fully utilized, there are tradeoffs, whether of radishes for carrots, leisure for money income, private goods for public goods, or present consumption for future consumption. In this way, marginalism is used as a tool for modeling economic systems and variables that affect them.

Economic reasoning

Economics relies on rigorous styles of argument. Economic method has several interacting parts:

- Formulation of testable models of economic relationships, for example, the relationship between the general level of prices and the general level of employment. This includes observable forms of economic activity, such as money, consumption, buying, selling, and prices.

- Collection of economic data. The data may include values of commodity prices and quantities, for example, the cost to hire a worker for a week, or the quantity purchased of a particular service.

- Production of economic statistics. Taking the data collected, and applying the model being used to produce a representation of economic activity. For example, the "general price level" is a theoretical idea common to macroeconomic models. The specific inflation rate involves taking measurable prices, and a model of how people consume, and calculating what the "general price level" is from the data within the model. For example, suppose that diesel fuel costs 1 euro a litre: to calculate the price level would require a model of how much diesel an average person uses, and what fraction of their income is devoted to this, but it also requires having a model of how people use diesel, and what other goods they might substitute for it.

- Reasoning within economic models. This process of reasoning (see the articles on informal logic, logical argument, fallacy) sometimes involves advanced mathematics. For instance, an established (though possibly unexamined) tradition among economists is to reason about economic variables in two-dimensional graphs in which curves representing relations between the axis variables are parameterized by various indices. A good example of this type of reasoning in Keynesian macroeconomics is the still commonly-used IS/LM model. Paul Samuelson's treatise Foundations of Economic Analysis examines the class of assertions called operationally meaningful theorems in economics, which are those that can be conceivably refuted by empirical data.[25] As usual in science, the conclusions obtained by reasoning have a predictive as well as confirmative (or dismissive) value. An example of the predictive value of economic theory is a prediction as to the effect of current deficits on interest rates 10 years into the future. An example of the confirmative value of economic theory would be confirmation (or dismissal) of theories concerning the relation between marginal tax rates and the deficit.

Economics typically employs two types of equations:

(1) Identity equations are used for defining how certain economic variables are calculated or related to each other. Identity equations are tautological in that the purpose is to define rather than to explain. An example is the value of national output, the price level times the quantity of output P•Q. Another example is Irving Fisher's equation of exchange P•Q = M•V. This relates the value of national output to the money supply and velocity of money. Given values of the other three terms in the equation, velocity V can be calculated.

(2) Descriptive equations are used to explain the behaviour of the economic agent(s) examined. For example, in the quantity theory of money, velocity in the equation of exchange is hypothesized to give a positive qualitative relation between the money supply and value of output or the price level. The point is not that V is a constant but that it is stable enough for changes in the money supply to help explain changes in the value of output or the price level.

Economists often formulate very simple models in order to isolate the impact of just one variable changing, for example, the ceteris paribus ("other things equal") assumption, meaning that all other things are assumed not to change during the period of observation: for example, "If the price of movie tickets rises, ceteris paribus the demand for popcorn falls." It is, however, possible with the use of econometric methods to determine one relationship while removing much of the noise caused by other variables.

Formal modeling has been adapted to some extent by all branches of economics. It is motivated by general principles of consistency and completeness. It is not identical to what is often referred to as mathematical economics; this includes, but is not limited to, an attempt to set microeconomics, in particular general equilibrium, on solid mathematical foundations.

Some reject mathematical economics. The Austrian School of economics believes that anything beyond simple logic is likely unnecessary and inappropriate for economic analysis. In fact, the entire empirical-deductive method sketched in this section may be rejected outright by that school.[citation needed]

Still, much of modern economics employs the hypothetico-deductive method to explain real-world phenomena. Towards this end, economics has undergone a massive formalization of its concepts and methods. This has included extension of microeconomic methods to analysis of seemingly non-economic areas, sometimes called economic imperialism.[26]

History of economics

Economic thought may be roughly divided into three phases: premodern (Greek, Roman, Arab), early modern (mercantilist and physiocrat) and modern (since Adam Smith in the late 18th century). Systematic economic theory has been developed mainly since the birth of the modern era. Joseph Schumpeter specifically credits the development of the scientific study of economics to the Late Scholastics, particularly those of 15th and 16th century Spain (see his History of Economic Analysis).

Classical economics

Publication of Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations in 1776, has been described as "the effective birth of economics as a separate discipline."[27] The approach that Smith helped initiate was later called 'classical economics'. It included such notables as Thomas Malthus, David Ricardo, and John Stuart Mill writing from about 1770 to 1870.[28]

Theories of value: classical and Marxist

Value theory was important in classical theory. Smith wrote that the "real price of every thing ... is the toil and trouble of acquiring it" as influenced by its scarcity. Smith maintained that, with rent and profit, other costs besides wages enter the price of a commodity.[29] Other classical economists presented variations on Smith, termed the 'labour theory of value'. In the work of Karl Marx, labour was fundamental. He argued that non-labour income under capitalist production was a diversion from labour, although concealed by appearances of "vulgar" political economy.[30][31]

Neoclassical economics

A body of theory later termed 'neoclassical economics' or 'marginalist economics' formed from about 1870 to 1910. The term 'economics' was popularized by neoclassical economists such as Alfred Marshall as a substitute for the earlier term 'political economy'. Neoclassical economics sytematized supply and demand as joint determinants of market price and quantity produced. It dispensed with the labour theory of value inherited from classical econonomics in favor of a marginal utility theory of value on the demand side and costs on the supply side.[32]

Other schools and approaches

There have been different and competing schools of economic thought pertaining to capitalism from the late 18th Century to the present day. Important schools of thought include Manchester school, Austrian school, Marxian economics, and Chicago school.

Within macroeconomics there is, in general order of their appearance in the literature; classical economics, Keynesian economics, neo-classical synthesis, post-Keynesian economics, monetarism, new classical economics, and supply-side economics. New alternative developments include evolutionary economics, dependency theory, and world systems theory.

Historic definitions of economics

This section extends the discussion of the definitions of Economics at the beginning of the article.

Wealth definition

The earliest definitions of political economy were simple, elegant statements defining it as the study of wealth. The first scientific approach to the subject was inaugurated by Aristotle, whose influence is still recognized, inter alia, today by the Austrian School. Adam Smith, author of the seminal work The Wealth of Nations and regarded by some as the 'father of economics', defines economics simply as "The science of wealth."[33] Smith offered another definition, "The Science relating to the laws of production, distribution and exchange."[33] Wealth was defined as the specialization of labour which allowed a nation to produce more with its supply of labour and resources. This definition divided Smith and Hume from previous definitions which defined wealth as gold. Hume argued that gold without increased activity simply serves to raise prices.[34]

John Stuart Mill defined economics as "The practical science of production and distribution of wealth"; this definition was adopted by the Concise Oxford English Dictionary even though it does not include the vital role of consumption. For Mill, wealth is defined as the stock of useful things.[35]

Definitions in terms of wealth emphasize production and consumption. The accounting measures usually used measure the pay received for work and the price paid for goods, and do not deal with the economic activities of those not significantly involved in buying and selling (for example, retired people, beggars, peasants). For economists of this period, they are considered non-productive, and non-productive activity is considered a kind of cost on society. This interpretation gave economics a narrow focus that was rejected by many as placing wealth in the forefront and man in the background; John Ruskin referred to political economy as a "bastard science"[36] and "the science of getting rich."[37]

Welfare definition

Later definitions evolved to include human activity, advocating a shift toward the modern view of economics as primarily a study of man and of human welfare, not of money. Alfred Marshall in his 1890 book Principles of Economics wrote, "Political Economy or Economics is a study of mankind in the ordinary business of Life; it examines that part of the individual and social action which is most closely connected with the attainment and with the use of material requisites of well-being."[38]

Schools of thought

Classical economics

Classical economics, also called political economy, was the original form of mainstream economics of the 18th and 19th centuries. Classical economics focuses on the tendency of markets to move to equilibrium and on objective theories of value. Neo-classical economics differs from classical economics primarily in being utilitarian in its value theory and using marginal theory as the basis of its models and equations. Marxist economics also descends from classical theory.

Marxian economics

Marxian economics derives from the work of Karl Marx, this school focuses on the labour theory of value and what Marx considered to be the exploitation of labour by capital. Thus, in Marxian economics, the labour theory of value is a method for measuring the exploitation of labour in a capitalist society, rather than simply a theory of price.[39][40]

Keynesian economics

This school has developed from the work of John Maynard Keynes and focused on macroeconomics in the short-run, particularly the rigidities caused when prices are fixed. It has two successors. Post-Keynesian economics is an alternative school - one of the successors to the Keynesian tradition with a focus on macroeconomics. They concentrate on macroeconomic rigidities and adjustment processes, and research micro foundations for their models based on real-life practices rather than simple optimizing models. Generally associated with Cambridge, England and the work of Joan Robinson (see Post-Keynesian economics). New-Keynesian economics is the other school associated with developments in the Keynesian fashion. These researchers tend to share with other Neoclassical economists the emphasis on models based on micro foundations and optimizing behavior but focus more narrowly on standard Keynesian themes such as price and wage rigidity. These are usually made to be endogenous features of these models, rather than simply assumed as in older style Keynesian ones (see New-Keynesian economics).

Neoclassical economics

Neoclassical economics is reflected in an early and lasting neoclassical synthesis with Keynesian macroeconomics,[41] and in the supply and demand model of markets. Is usually used as a starting point for microeconomics. It represent incentives and costs as playing a pervasive role in shaping decision making. An immediate example of this is the consumer theory of individual demand, which isolates how prices (as costs) and income affect quantity demanded.

Neoclassical economics is often referred as orthodox economics whether by its critics or sympathizers. The notion of opportunity cost is a refinment of neoclassical analyis. It expresses an implied relationship between competing alternatives. Such costs, considered as prices in a market economy are used for analysis of economic efficiency or for predicting responses to disturbances in a market. In a planned economy comparable shadow price relations must be satisfied for the efficient use of resources, as first demonstrated out by the Italian economist Enrico Barone.

Modern mainstream economics builds on neoclassical economics but with many refinements that either supplement or generalize earlier analysis, such as econometrics, game theory, analysis of market failure and imperfect competition, and the neoclassical model of economic growth for analyzing long-run variables affecting national income.

Other schools

Other famous schools or trends of thought referring to a particular style of economics practiced at and disseminated from well-defined groups of academicians that have become known worldwide, include the Austrian School, Chicago School, the Freiburg School, the School of Lausanne and the Stockholm school.

Economic theory criticisms

Is economics a science?

One of the marks of a science is the use of a scientific method and the ability to establish hypotheses and make predictions which can then be tested with data and where the results are repeatable and demonstrable to others when the same conditions are present. In a number of applied fields in economics experimentation has been conducted: this includes the sub-fields of experimental economics and consumer behavior, focused on experimentation using human subjects; and the sub-field of econometrics, focused on testing hypotheses when data are not generated via controlled experimentation. However, in a way similar to what happens in other social sciences, it may be difficult for economists to conduct certain formal experiments due to moral and practical issues involved with human subjects.

The status of social sciences as an empirical science has been a matter of debate in the 20th century, see Positivism dispute.[42] Some philosophers and scientists, most notably Karl Popper, have asserted that no empirical hypothesis, proposition, or theory can be considered scientific if no observation could be made which might contradict it, insisting on strict falsifiability. Critics allege that economics cannot always achieve Popperian falsifiability, but economists point to many examples of controlled experiments that do exactly this. [43][44][45]

While economics has produced theories that correlate with observations of behavior in society, economics yields no natural laws or universal constants due to its reliance on non-physical arguments. This has led some critics to argue economics is not a science.[46] In general, economists reply that while this aspect may present serious difficulties, they do in fact test their hypotheses using statistical methods such as econometrics and data generated in the real world.[47] The field of experimental economics has seen efforts to test at least some predictions of economic theories in a simulated laboratory setting – an endeavor which earned Vernon Smith and Daniel Kahneman the Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel in 2002.

Although the conventional way of connecting an economic model with the world is through econometric analysis, economist and professor Deirdre McCloskey, through what is known as the McCloskey critique, cites many examples in which professors of econometrics were able to use the same data to both prove and disprove the applicability of a model's conclusions. She argues the vast efforts expended by economists on analytical equations is essentially wasted effort. Econometricians have replied that this would be an objection to any science, and not only to economics. Critics of McCloskey's critique reply by saying, among other things, that she ignores examples where economic analysis is conclusive and that her claims are illogical. [48]

Criticism of assumptions

Certain models used by economists within economics have been criticized, sometimes by other economists, for their reliance on unrealistic, unobservable, or unverifiable assumptions. One response to this criticism has been that the unrealistic assumptions result from abstraction from unimportant details, and that such abstraction is necessary in a complex real world, which means that rather than unrealistic assumptions compromising the epistemic worth of economics, such assumptions are essential for economic knowledge. One study has termed this explanation the "abstractionist defense" and concluded that that this "abstractionist defense" does not invalidate the criticism of the unrealistic assumptions.[49] However, it is important to note that while one school does have a majority in the field, there is far from a consensus on all economic issues and multiple alternative fields claim to have more empirically-justified insights.

Assumptions and observations

Many criticisms of economics revolve around the belief that the fundamental claims of economics are unquestioned assumption without empirical evidence. Many economists reply giving examples of concepts that used to be considered "axioms" in economics and which have turned out to be consistent with empirical observation (see three examples below), however agreeing that these observations reveal that the original assumption was probably oversimplified.

A few examples of such concepts that according to many economists have evolved from "assumptions" to empirically-based are:

- Rationality = Self-Interest: This refers to the common axiom or belief shared by many mainstream economists that rationality implies self-interest and vice-versa. This does not, however, preclude altruism. Altruism can be viewed as a case in which the individual's self-interest includes doing good for others. Other views claim that this does not leave much room for altruism, and in fact discourages it, rather like a global prisoner's dilemma .i.e.: If "rational" people are not altruistic, then I shouldn't be altruistic either, ad infinitum. However, this "axiom" has since been subjected to multiple experiments and even altruism, when all social pressures are considered, could be modeled as a form of self-interest. [50][51]

- Well-Being = Consumption: This refers to the axiom or belief shared by some mainstream economists that human beings are happy when they consume, and unhappy when not consuming. Added to the other common assumption of insatiability, this implies human beings can never remain happy. Although this original belief is over-simplified (and perhaps not representative of most economists actual beliefs today), empirical observations have now confirmed a relationship between sense of well-being and such factors as income [52]

- Atomism: This refers to the belief shared by some mainstream economists that human beings are atomistic, ie.their preferences are independent. This is another simplification both of the economy and of the specific beliefs of the economists. Agent-based modeling and experimental economics produce results that are indicative of this theory.

A common defense of the above axioms was that they made the problem tractable. However, after specific details of this have been observed through economics research in a variety of controlled experiments, the original assumptions have been further refined and are no longer technically "axioms" in mainstream economics.

Criticism of contradictions

Economics is a field of study with various schools and currents of thought. As a result, there exists a considerable distribution of opinions, approaches and theories. Some of these reach opposite conclusions or, due to the differences in underlying assumptions, contradict each other.[53][54][55]

Criticisms of welfare and scarcity definitions of economics

The definition of economics in terms of material being is criticized as too narrowly materialistic. It ignores, for example, the non-material aspects of the services of a doctor or a dancer. A theory of wages which ignored all those sums paid for immaterial services was incomplete. Welfare could not be quantitatively measured, because the marginal significance of money differs from rich to the poor (that is, $100 is relatively more important to the well-being of a poor person than to that of a wealthy person). Moreover, the activities of production and distribution of goods such as alcohol and tobacco may not be conducive to human welfare, but these scarce goods do satisfy innate human wants and desires.

Marxist economics still focuses on a welfare definition. In addition, several critiques of mainstream economics begin from the argument that current economic practice does not adequately measure welfare, but only monetized activity, which is an inadequate approximation of welfare.

The definition of economics in terms of scarcity suggests that resources are in finite supply while wants and needs are infinite. People therefore have to make choices. Scarcity too has its critics. It is most amenable to those who consider economics a pure science, but others object that it reduces economics merely to a valuation theory. It ignores how values are fixed, prices are determined and national income is generated.[citation needed] It also ignores unemployment and other problems arising due to abundance. This definition cannot apply to such Keynesian concerns as cyclical instability, full employment, and economic growth.

The focus on scarcity continues to dominate neoclassical economics, which, in turn, predominates in most academic economics departments. It has been criticized in recent years from a variety of quarters, including institutional economics and evolutionary economics and surplus economics.

Criticism in other topics

Criticism on several topics in economics can be found elsewhere, in both general and specialized literature. See, for example: general equilibrium, Pareto efficiency, marginalism, behavioral finance, behavioral economics, feminist economics, Keynesian economics, monetarism, neo-classical economics, endogenous growth theory, comparative advantage, Kuznets curve, Laffer curve, economic sociology, agent-based computational economics, et al..

Economics and politics

Some economists (ex. J.S.Mill, Leon Walras) have maintained that the production of wealth should not be tied to its distribution. The former is in the field of "applied economics" while the latter belongs to "social economics" and is largely a matter of (power)politics.[56]

Economics per se, as a social science, do not stand on the political acts of any government or other decision-making organization, however, many policymakers or individuals holding highly ranked positions that can influence other people's lives are known for arbitrarily use a plethora of economic theory concepts and rhetoric as vehicles to legitimize agendas and value systems, and do not limit their remarks to matters relevant to their responsibilities.[57] The close relation of economic theory and practice with politics[58] is a focus of contention that may shade or distort the most unpretentious original tenets of economics, and is often confused with specific social agendas and value systems.[59] For example, it is possible associate the U. S. promotion of democracy by force in the 21st century, the 19th century work of Karl Marx or the cold war era debate of capitalism vs. communism, as issues of economics. Although economics makes no such value claims, this may be one of the reasons why economics could be perceived as not being based on empirical observation and testing of hypothesis. As a social science, economics tries to focus on the observable consequences and efficiencies of different economic systems without necessarily making any value judgments about such systems, for example, examine the economics of authoritarian systems, egalitarian systems, or even a caste system without making judgments about the morality of any of them.

Ethics and economics

The relationship between economics and ethics is complex. Many economists consider normative choices and value judgments, like what needs or wants, or what is good for society, to be political or personal questions outside the scope of economics. Once a person or government has established a set of goals, however, economics can provide insight as to how they might best be achieved.

Others see the influence of economic ideas, such as those underlying modern capitalism, to promote a certain system of values with which they may or may not agree. (See, for example, consumerism and Buy Nothing Day.) According to some thinkers, a theory of economics is also, or implies also, a theory of moral reasoning.[60]

The premise of ethical consumerism is that one should take into account ethical and environmental concerns, in addition to financial and traditional economic considerations, when making buying decisions.

On the other hand, the rational allocation of limited resources toward public welfare and safety is also an area of economics. Some have pointed out that not studying the best ways to allocate resources toward goals like health and safety, the environment, justice, or disaster assistance is a sort of willful ignorance that results in less public welfare or even increased suffering.[61] In this sense, it would be unethical not to assess the economics of such issues. In fact, federal agencies in the United States routinely conduct economic analysis studies toward that end.

Effect on society

Some would say that market forms and other means of distribution of scarce goods, suggested by economics, affect not just their "desires and wants" but also "needs" and "habits". Much of so-called economic "choice" is considered involuntary, certainly given by social conditioning because people have come to expect a certain quality of life. This leads to one of the most hotly debated areas in economic policy, namely, the effect and efficacy of welfare policies. Libertarians view this as a failure to respect economic reasoning. They argue that redistribution of wealth is morally and economically wrong. Socialists view it as a failure of economics to respect society. They argue that disparities of wealth should not have been allowed in the first place. This led to both 19th century labour economics and 20th century welfare economics before being subsumed into human development theory.

The older term for economics, political economy, is still often used instead of "economics", especially by certain economists such as Marxists. The use of this term often signals a basic disagreement with the terminology or paradigm of market economics. Political economy explicitly brings social political considerations into economic analysis and is therefore openly normative, although this can be said of many economic recommendations as well, despite claims to being positive. Some mainstream universities (many in the United Kingdom) have a "political economy" department rather than an "economics" department.

Marxist economics generally denies the trade-off of time for money. In the Marxist view, concentrated control over the means of production is the basis for the allocation of resources among classes. Scarcity of any particular physical resource is subsidiary to the central question of power relationships embedded in the means of production.

Notes

- ^ Ng, Yew-Kwang (1992). "Business Confidence and Depression Prevention: A Mesoeconomic Perspective," American Economic Review 82(2), pp. 365-371. [1]

- ^ Howitt, Peter M. (1987). "macroeconomic relations with microeconomics".The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, pp. 273-75. London and New York: Macmillan and Stockton. ISBN 0-333-37235-2.

- ^ The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics. London and New York: Macmillan and Stockton. 1987. ISBN 0-333-37235-2 and ISBN 0-935859-10-1.

{{cite book}}:|first=missing|last=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Debreu, Gerard (1987). "mathematical economics," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, pp. 401-03.

- ^ Hashem, M. Pesaren (1987). "econometrics", The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 2, p. 8.

- ^ Aumann, R.J. (1987). "game theory ," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 2, pp. 460-82.

- ^ Ruggles, Nancy D. (1987). "social accounting". The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economicsdate=. London and New York: Macmillan and Stockton. pp. v. 3, 377. ISBN 0-333-37235-2.

- ^ Bell, Clive (1987). "development economics," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 1, pp. 818-26.

- ^ Kneese, Allen K., and Clifford S. Russell (1987). "environmental economics," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 2, pp. 159-64.

- ^ Samuelson, Paul A., and William D. Nordhaus (2004). Economics, ch. 18, "Protecting the Environment." McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-287205-5.

- ^ Ross, Stephen A. (1987). "finance," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 2, pp. 322-26.

- ^ Schmalensee, Richard (1987). "industrial organization," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 2, pp. 803-808.

- ^ Freeman, R.B. (1987). "labour economics," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, pp. 72-76.

- ^ Friedman, David (1987). "law and economics," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, p. 144.

- ^ Posner, Richard A. (1972). Economic Analysis of Law. Aspen, 7th ed., 2007) ISBN 978-0-735-56354-4.

- ^ Coase, Ronald, "The Problem of Social Cost", The Journal of Law and Economics Vol.3, No.1 (1960). This issue was actually published in 1961.

- ^ Musgrave, R.A. (1987). "public finance," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, pp. 1055-60.

- ^ Feldman, Allan M. ((1987). "welfare economics," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 4, pp. 889-95.

- ^ Baumol, William J. (2007). "Economic Theory" (Measurement and ordinal utility). The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, v. 17, p. 719.

- ^ Hicks, John Richard (1939). Value and Capital. London: Oxford University Press. 2nd ed., paper, 2001. ISBN 978-0198282693.

- ^ Brody, A. (1987). ""prices and quantities,"," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, p. 957.

- ^ Jordan, J.S. (1982). "The Competitive Allocation Process Is Informationally Efficient Uniquely." Journal of Economic Theory, 28(1), p. 1-18.

- ^ Blaug, Mark (2007). "The Social Sciences: Economics". The New Encyclopaedia Britannicav. 27, p. 347. Chicago. ISBN 0852294239}}

- ^ Laffont, J.J. (1987). "externalities,"," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 2, p. 263-65.

- ^ Samuelson, Paul (1947, 1983). Foundations of Economic Analysis, Enlarged Edition. Boston: Harvard University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0674313019.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Lazear, Edward P. (2000). "Economic Imperialism," The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(1) , pp. 99-146 (via JSTOR).

- ^ Blaug, Mark (2007). "The Social Sciences: Economics". The New Encyclopaedia Britannica. Chicago: The New Encyclopaedia Britannica. pp. v. 27, p. 343. ISBN 0852294239.

- ^ Blaug, Mark (1987). "classical economics". The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 1, pp. 434-35 Blaug notes less widely used datings and uses of 'classical economics', including those of Marx and Keynes.

- ^ Smith, Adam (1776). The Wealth of Nations, Bk. 1, Ch. 5, 6.

- ^ Vianello, Fernando (1987). "labour theory of value," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, pp. 111-12.

- ^ Baradwaj Krishna (1987). "vulgar economy," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, p. 831.

- ^ Campos, Antonietta (1987). "marginalist economics". The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics. London and New York: Macmillan and Stockton. pp. v. 3, 320. ISBN 0333372352.

- ^ a b Smith, Adam (1776). Wealth of Nations, edited by C. J. Bullock. Vol. X. The Harvard Classics. New York: P.F. Collier & Son, 1909–14; Bartleby.com, 2001.

- ^ Hume, David; Copley, Stephen and Edgar, Andrew, editors (1998). "Of the Balance of Trade" Selected Essays. New York: Oxford University Press, USA. p. 188. ISBN 978-0192836212.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Mill, John Stuart (1848). Principles of Political Economy with Some of Their Applications to Social Philosophy. Boston: C.C. Little & J. Brown. pp. 1, 8. ISBN 978-0192836212.

- ^ Ruskin, John (1860). "Ad Valorem". Cornhill Magazine. Retrieved 2007-03-17. Reprinted as Unto This Last, 1862

- ^ Ruskin, John (1860). "The Veins of Wealth". Cornhill Magazine. Retrieved 2007-03-17. Reprinted as Unto This Last, 1862

- ^ Marshall, Alfred (1890). Principles of Economics. London: Macmillan and Co., Ltd. pp. 8th ed., 1920, I.I.1.

- ^ Roemer, J.E. (1987). "Marxian Value Analysis". The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics. London and New York: Macmillan and Stockton. pp. v. 3, 383. ISBN 0333372352.

- ^ Mandel, Ernest (1987). "Marx, Karl Heinrich". The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics. London and New York: Macmillan and Stockton. pp. v. 3, 372, 376. ISBN 0333372352.

- ^ Hicks, J.R. (1937). "Mr. Keynes and the 'Classics': A Suggested Interpretation," Econometrica, 5(2), pp. [147-159 (via JSTOR).

- ^ Critical examination of various positions on this issue can be found in Karl R. Popper's The Poverty of Historicism (1957). London and New York: Routledge; reprint ed. 1988 (paper). ISBN 9780415065696

- ^ The Economics of Fair Play. Karl Sigmund, Ernst Fehr and Martin A. Nowak in Scientific American, Vol. 286, No. 1, pages 82-87; January 2002

- ^ The Nature of Human Altruism. Ernst Fehr and Urs Fischbacher in Nature, Vol. 425, pages 785-791; October 23, 2003.

- ^ Andrew Oswald, ‘‘Happiness and Economic Performance,’’ Economic Journal 107 (1997): p. 1815–1831.

- ^ Richardson, Dick (2001-01-28). "Economics is NOT Natural Science! (It is technology of Social Science.)". R.H. Richardson. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ Roth, Alvin E. (1999). "Is Economics a Science? (Of course it is...)". Unpublished letter to the Economist. Alvin E. Roth. Retrieved 2007-03-17. Roth is the Gund Professor of Economics and Business Administration, Harvard Economics Department and Harvard Business School

- ^ CORRESPONDENCE - Econ Journal Watch, Volume 1, Number 3, December 2004, pp 539-545

- ^ Rappaport, Steven (December 1996). "Abstraction and unrealistic assumptions in economics". Volume 3 Number 2. Journal of Economic Methodology. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ^ The Economics of Fair Play. Karl Sigmund, Ernst Fehr and Martin A. Nowak in Scientific American, Vol. 286, No. 1, pages 82-87; January 2002

- ^ The Nature of Human Altruism. Ernst Fehr and Urs Fischbacher in Nature, Vol. 425, pages 785-791; October 23, 2003.

- ^ Andrew Oswald, ‘‘Happiness and Economic Performance,’’ Economic Journal 107 (1997): p. 1815–1831.

- ^ Frey, Bruno S.; Pommerehne, Werner W.; Schneider, Friedrich; Gilbert, Guy (December 1984). "Consensus and Dissension Among Economists: An Empirical Inquiry". The American Economic Review. 74 (5): 986-994.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Accessed on 2007-03-17. - ^ McCloskey, Deirdre N. (1983–2005). "Rhetorical Criticism in Economics". Articles by Deirdre McCloskey. www.deirdremccloskey.org. Retrieved 2007-03-17. McCloskey is Distinguished Professor of Economics, History, English, and Communication at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

- ^ McCloskey, D. N. (1985) The Rhetoric of Economics [2] (Madison, University of Wisconsin Press).

- ^ The Origin of Economic Ideas, Guy Routh (1989)

- ^ Dr. Locke Carter (Summer 2006 graduate course) - Texas Tech University

- ^ Research Paper No. 2006/148 Ethics, Rhetoric and Politics of Post-conflict Reconstruction How Can the Concept of Social ContractHelp Us in Understanding How to Make Peace Work? Sirkku K. Hellsten, pg. 13

- ^ Political Communication: Rhetoric, Government, and Citizens, second edition, Dan F. Hahn

- ^ E.F.Schumacher: Small is Beautiful, Economics as if People matter.

- ^ Douglas Hubbard, "How to Measure Anything: Finding the Value of Intangibles in Business", John Wiley & Sons, 2007.

See also

- Related topics

- Advertising

- Bank of Sweden Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel

- Barter

- Computational economics

- Debt-based monetary system

- Dismal Science

- EAEPE

- Climate Change

- Economic aid

| class="col-break " |

- Economic calendar

- Economic depression

- Economic development

- Economic indicators

- Economic recession

- Economic sanction

- Economic sociology

- Economies of present-day nations and states

- Ecological Economics

- Feminist economics

- Economist

- Exchange rate

- Global economy

- Gross national happiness

- Gross Domestic Product

- Gross National Product

| class="col-break " |

- Happiness economics

- Marketing

- Monetary policy

- Money

- Money supply

- Oligopolistic

- Socioeconomics

- Supply

- Trade

- Trade deficit

- Trade surplus

- US dollar

- Wealth

- World Bank

- World economy

- Lists

- List of economics topics

- List of basic economics topics

- List of accounting topics

- List of business ethics, political economy, and philosophy of business topics

- List of business law topics

- List of economic geography topics

| class="col-break " |

- List of economic systems

- List of economists

- List of finance topics

- List of human resource management topics

- List of information technology management topics

- List of international trade topics

| class="col-break " |

- List of management topics

- List of marketing topics

- List of production topics

- List of publications in economics

- List of scholarly journals in economics

- List of video lectures in economics

Further reading

- Frontiers in Economics - ed. K. F. Zimmermann, Springer-Science, 2002. - A summary of surveys on different areas in economics.

- The Autistic Economist - Yale Economic Review - How and why the dismal science embraces theory over reality.

- Nature of Things by Jean-Baptiste Say - an essay in which Say claims that economics is not an ethical system that one can simply refute on the basis that one does not accept its values: it is a collection of theories and models that explain inductively found principles.

External links

General information

- Economics at Curlie

- Resources For Economists: Official resource guide of the American Economic Association

- Research Papers in Economics (RePEc): huge database of preprints and other research

- Economic journals on the web

- Intute: Economics: Searchable human catalogue of the best links for teaching and research in Economics

Institutions and organizations

- Economics Departments, Institutes and Research Centers in the World

- Organization For Co-operation and Economic Development (OECD) Statistics

- United Nations Statistics Division

- World Bank Data

- World Trade Organization

- Center for Economic and Policy Research (USA)

Study resources

- Economics textbooks on Wikibooks

- MERLOT Learning Materials: Economics: US-based database of learning materials

- The United economic encyclopedia

- Online Learning and Teaching Materials for Economics: The Economics Network (UK)'s database of text, slides, glossaries and other resources

- MIT OpenCourseWare: Economics: Archive of study materials from MIT courses

- A guide to several online economics textbooks

- The Library of Economics and Liberty (Econlib): Economics Books, Articles, Blog (EconLog), Podcasts (EconTalk)

- Schools of Thought: Compare various economic schools of thought on particular issues

- Economics at About.com

- Bized–A UK-based portal site for Economics and Business Studies designed mainly for UK students.

- Ask The Professor section of EH. Net Economic History Services

- Introduction to Economics: Short Creative commons-licensed introduction to basic economics