The Hobbit: Difference between revisions

→Adaptations: added reference, fixed info. |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 121: | Line 121: | ||

Several [[Video game|computer and video games]], both official and unofficial, have been based on the story. One of the first was ''[[The Hobbit (video game)|The Hobbit]]'', an award winning (Golden Joystick Award for Strategy Game of the Year 1983) computer game developed in 1982 by Beam Software and published by [[Melbourne House]] for most computers available at the time, from the more popular computers such as the [[ZX Spectrum]], and the [[Commodore 64]], through to the [[Dragon 32/64|Dragon 32]] and [[Oric Atmos|Oric]] computers. By arrangement with publishers, a copy of the novel was included with each game sold. [[Sierra Entertainment]] published a [[platform game]] titled ''[[The Hobbit (Vivendi Game)|The Hobbit]]'' in 2003 for [[Microsoft Windows|Windows]] [[personal computer|PCs]], [[PlayStation 2]], [[Xbox]], and [[GameCube|Nintendo GameCube]]. It was a similar version of which was also published for the [[Game Boy Advance]]. |

Several [[Video game|computer and video games]], both official and unofficial, have been based on the story. One of the first was ''[[The Hobbit (video game)|The Hobbit]]'', an award winning (Golden Joystick Award for Strategy Game of the Year 1983) computer game developed in 1982 by Beam Software and published by [[Melbourne House]] for most computers available at the time, from the more popular computers such as the [[ZX Spectrum]], and the [[Commodore 64]], through to the [[Dragon 32/64|Dragon 32]] and [[Oric Atmos|Oric]] computers. By arrangement with publishers, a copy of the novel was included with each game sold. [[Sierra Entertainment]] published a [[platform game]] titled ''[[The Hobbit (Vivendi Game)|The Hobbit]]'' in 2003 for [[Microsoft Windows|Windows]] [[personal computer|PCs]], [[PlayStation 2]], [[Xbox]], and [[GameCube|Nintendo GameCube]]. It was a similar version of which was also published for the [[Game Boy Advance]]. |

||

===Movie=== |

|||

''The Hobbit'' prequel to ''Lord of the Rings'' has been confirmed to start filming two films in 2009 simultaneously, with the first film releasing in 2010 and the second film releasing in 2011. Peter Jackson will be the Executive Producer but no name of a director has been announced. |

|||

<ref>http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/22312421/ |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

Revision as of 17:51, 18 December 2007

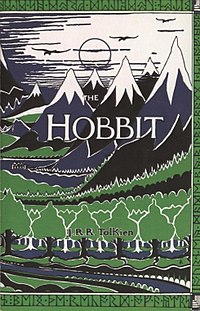

Cover to the 1937 first edition | |

| Author | J. R. R. Tolkien |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | J. R. R. Tolkien |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Fantasy novel, Children's literature |

| Publisher | George Allen & Unwin (UK) & Houghton Mifflin Co. (U.S.) |

Publication date | 1937 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) & Audio book |

| ISBN | NA Parameter error in {{ISBNT}}: invalid character |

| Preceded by | The Silmarillion |

| Followed by | The Lord of the Rings |

Template:Middle-earth portal The Hobbit, or There and Back Again is a fantasy novel [1][2][3] written by J. R. R. Tolkien in the tradition of the fairy tale. It was first published on September 21, 1937 to wide acclaim. While it stands in its own right, it is often marketed as a prelude to Tolkien's monumental novel The Lord of the Rings.

Overview

The Hobbit is set in a time "between the dawn of Faerie and the Dominion of Men",[4] and follows the quest of home-loving Bilbo Baggins (the "Hobbit" of the title) as he leaves his comedic-rustic village and moves into darker, deeper territory[5] along with the thirteen dwarves and wizard Gandalf. He encounters various denizens of the Wilderland, in order to reach and win his share of Smaug, the Dragon's, hoard. Through accepting the nature of his "Tookish" half (a disrespectable, romantic, fey and adventurous side of his family tree) and utilising both his wits and common sense during the quest, Bilbo develops a new level of maturity, competence and wisdom.[6]

Characters in The Hobbit

- Bilbo Baggins, the titular protagonist, a respectable, comfort-loving, middle-aged hobbit.

- Gandalf, an itinerant wizard who introduces Bilbo to a company of thirteen dwarves and then disappears and reappears at key points in the story.

- Thorin Oakenshield, bombastic head of the company and heir to a dwarven kingdom under the Lonely Mountain.

- Smaug, a dragon who long ago pillaged the dwarven kingdom of Thorin's grandfather.

The plot involves a host of other characters of varying importance, such as the twelve other dwarves of the company; elves; men (humans); trolls; goblins; giant spiders; eagles; Wargs (evil wolves); Elrond the sage; Gollum, a mysterious creature inhabiting an underground lake; Beorn, a man who can assume bear-form; and Bard the Bowman, a heroic archer of Lake-town.

Synopsis

Gandalf tricks Bilbo into hosting a planning party for Thorin's band of dwarves, whose ambition is to reclaim the Lonely Mountain and its vast treasure from the Dragon Smaug. During the council Gandalf unveils a map showing a secret door into the Mountain and proposes that the dumbfounded Bilbo be the expedition's "burglar". The dwarves ridicule the idea, but Bilbo, indignant, joins despite himself.

The group travels into the wild, where Gandalf saves the company from trolls. Their path takes them into the Misty Mountains. There they are captured by goblins and driven deep underground. Though Gandalf frees them, Bilbo gets separated from the others as they flee the goblin tunnels. Groping along lost, he finds a ring and encounters Gollum, who engages him in a game of riddles. Bilbo wins, but Gollum, suspecting Bilbo has his precious ring, tries to kill him anyway. With the help of the ring, which confers invisibility, Bilbo escapes and rejoins the company. His success raises his reputation. Gandalf departs on a private errand, and the rest enter the black forest of Mirkwood, where Bilbo first saves the dwarves from giant spiders and then from the dungeons of the Wood-elves. By this time Bilbo is the de facto leader.

Nearing the Lonely Mountain, the travellers are welcomed by the human inhabitants of Lake-town, who hope the dwarves will fulfill prophecies of Smaug's demise. The expedition travels to the Mountain and finds the secret door; Bilbo scouts the dragon's lair, stealing a great cup and learning of a weakness in Smaug's armour. The enraged dragon, deducing that Lake-town aided the intruder, sets out to destroy the town. A noble thrush who overheard Bilbo's report of Smaug's vulnerability reports it to Bard the Bowman, who slays the Dragon.

When the dwarves take possession of the mountain, Bilbo finds the prized Arkenstone gem and hides it away. The Wood-elves and Lake-men besiege the Mountain and request compensation for their aid, reparations for Lake-town's destruction, and settlement of old claims on the treasure. Thorin refuses and, having summoned his kin from the north, reinforces his position. Bilbo tries to ransom the Arkenstone to head off a war, but Thorin is intransigent. He banishes Bilbo, and battle seems inevitable.

Gandalf reappears to warn all of an approaching army of goblins and Wargs. The dwarves, men, and elves band together, but only with the timely arrival of the eagles and Beorn is the Battle of Five Armies won. Thorin, mortally-wounded, lives long enough to part from Bilbo as friends. The treasure is divided fairly, but, having no need or desire for it, Bilbo refuses most of his contracted share. Nevertheless, he returns home with enough to make himself a very wealthy hobbit.

Concept and creation

Writing

In a 1955 letter to W. H. Auden, Tolkien recollects that in the late 1920s, when he was Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Pembroke College, he began The Hobbit when he was marking School Certificate papers. He found one blank page. Suddenly inspired he wrote the words "In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit." He did not go any further than that at the time, although in the following years he drew up Thrór's map, outlining the geography of the tale, and by January 1933 had finished the story: C. S. Lewis read it that month with great enthusiasm. It was eventually published when a family friend and student of Tolkien's named Elaine Griffiths was lent the typescript of the story in 1936. When Griffiths was visited in Oxford by Susan Dagnall, a staffmember of the publisher George Allen & Unwin, she either lent Dagnall the book or suggested she borrow it from Tolkien (the sources are unclear). In any event, Miss Dagnall, impressed by it, showed the book to Stanley Unwin, who then asked his 10-year-old son Rayner to review it. Rayner wrote such an enthusiastic review of the book that it was published by Allen & Unwin.

Publication

George Allen & Unwin, Ltd. of London published the first edition of The Hobbit on September 21, 1937. It was illustrated with many black-and-white drawings by Tolkien himself. The original printing numbered a mere 1,500 copies and sold out by December due to enthusiastic reviews.[7] Houghton Mifflin of Boston and New York prepared an American edition to be released early in 1938 in which four of the illustrations would be colour plates. Allen & Unwin decided to incorporate the colour illustrations into their second printing, released at the end of 1937.[7] Despite the book's popularity, wartime conditions forced the London publisher to print small runs of the remaining two printings of the first edition.

The first printing of the first English language edition can sell for between £6000[8] and £20,000 at auction.[9] , although the price has occasionally reached over £40,000.[10]

New English-language editions of The Hobbit spring up often, despite the book's age, with at least fifty editions having been published to date. Each comes from a different publisher or bears distinctive cover art, internal art, or substantial changes in format. The text of each generally adheres to the Allen & Unwin edition extant at the time it is published. In addition, the Hobbit has been translated into over forty languages. Some languages have seen multiple translations.

Revisions

In December 1937, Tolkien's publishers asked for a sequel, so the author began work on what would become the much larger The Lord of the Rings.

In the first edition of The Hobbit, Gollum willingly bets his magic ring on the outcome of the riddle-game, and he and Bilbo part amicably.[11] During the writing of The Lord of the Rings Tolkien saw the need to revise these passages, in order to reflect his new concept of the ring and its powerful hold on Gollum. Tolkien tried many different passages in the chapter that would become chapter 2 of The Lord of the Rings, "The Shadow of the Past". Eventually Tolkien decided a rewrite of the Gollum encounter in The Hobbit was in order, and he sent a revised version to his publishers. He heard nothing further for years. When he was sent galley proofs of a new edition he learned to his surprise the new chapter had been incorporated as the result of a misunderstanding [12]

In The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien retroactively establishes that the events of The Hobbit take place during the "Third Age" of Middle-earth,[13] a fictional prehistoric Earth[13][14]. He presents himself as the translator of the supposedly historic Red Book of Westmarch, where Bilbo and Frodo's stories were recorded. In the book's prologue, as well as in the chapter "The Shadow of the Past", Tolkien explains the original version of the riddle-game as a "lie" that Bilbo made up because of the One Ring's influence on him, and which he originally wrote down in his diary, the basis of The Hobbit. Revised versions of The Hobbit would contain the "true" version of events.[13] This first revision became the second edition, published in 1951 in both UK and American editions.[7]

In order to conform the narrative both to events in The Lord of the Rings and to the ideas he was continually developing for the Quenta Silmarillion.[15], Tolkien made minor changes to the third (1966).[16] For example, the phrase elves that are now called Gnomes appears in the first[17] and second[18] editions on page 63. Tolkien had used "Gnome" in his earlier writing to refer to the second kindred of the High Elves – the Noldor (or "Deep Elves"). Tolkien thought that "gnome", being derived from the Greek gnosis (knowledge), was a good name for the wisest of the Elves, but with its common denotation of a garden gnome, Tolkien ultimately replaced the phrase with High Elves of the West, my kin in the third edition[19].

In its final revision, The Hobbit still retains many differences in tone from The Lord of the Rings. For example, goblins are more often referred to as Orcs in The Lord of the Rings.[20] Many of the inconsistencies arose because Tolkien wrote the Hobbit as a children's story largely independent of his mythological writing, only later strengthening the connections through revisions and through its sequel. [12] Moreover, his concept of Middle-earth was to change and evolve throughout his life and writings.[21]

Publication of early drafts

In May and June 2007, HarperCollins and Houghton Mifflin published The History of The Hobbit in the United Kingdom. Much like The History of Middle-earth, The History of The Hobbit examines in two volumes previously unpublished original drafts of The Hobbit with extensive commentary by John Rateliff. In celebration and recognition of the 70th anniversary of The Hobbit, The History was published in the United States on September 21, 2007, exactly 70 years after the initial publication of Tolkien's work.

Style

The basic form of the story is that of a quest, told in episodes. Tolkien fills the story with a wealth of detail regarding minor characters and distant events which can make his imaginary world seem to have more depth, but has been seen by certain readers[who?] to slow down the pace.[citation needed] The narrative voice often addresses the reader directly, a device which the author himself came to dislike.[22] (Humphrey Carpenter's biography of Tolkien claims he had to restrain himself from rewriting the book entirely when revising it after a period of nearly 20 years.[12])

The novel draws on Tolkien's knowledge of historical languages and early European texts, the names of Gandalf and all but one of the thirteen dwarves being taken directly from the Old Norse poem "Voluspa" from the Elder Edda.[23] and its illustrations (provided by the author) make use of Anglo-Saxon runes. The story is filled with information on calendars and moon phases, detailed geographical descriptions that fit well with the accompanying maps — attention to detail that is also found in Tolkien's later work.

Major themes

The central character, Bilbo, is a modern anachronism exploring an essentially antique world, yet the character is able to negotiate and interact within it because of the connections between the modern and antique worlds through language and tradition. Gollum's riddles are taken from old historical sources, while those of Bilbo from modern nursery books. The familiar form of the riddle-game allows the two characters to discourse, rather than the content of the riddles themselves. This idea of a superficial contrast in characters' linguistic style leading to an understanding of the deeper unity is a constant recurring theme throughout The Hobbit. [24]

The Hobbit may be read as Tolkien's parable of the First World War, where the hero is plucked from his rural home, and thrown into a far off war where traditional types of heroism are shown to be futile[25] and as such explores the theme of heroism.

The Jungian concept of individuation is reflected through theme of growing maturity and capability, with the author seen to be contrasting Bilbo's personal growth against the lack of that of the dwarves. [6]

Greed plays a central role in the novel, with many of the episodes stemming from one or more of the characters simple desire for food (be it trolls eating dwarves, or dwarves eating Wood-elf fare) or a desire for beautiful objects, such as gold and jewels.[26]

Adaptations

March 1953 saw the first authorised adaptation — a production by St. Margaret's School, Edinburgh.[27] Since then The Hobbit has been adapted for other media many times.

BBC Radio 4 broadcast The Hobbit radio drama, adapted by Michael Kilgarriff, in eight parts (4 hours) from September to November 1968, which starred Anthony Jackson as narrator, Paul Daneman as Bilbo and Heron Carvic as Gandalf.

Nicol Williamson's abridged reading of the book was released on four LP records in 1974 by Argo Records.

The Hobbit, an animated version of the story, produced by Rankin/Bass, debuted as a television movie in the United States in 1977.

The American radio theatre company The Mind's Eye produced an audio adaptation of "The Hobbit" which was released on six one-hour audio cassettes in 1979.

The BBC children's television series Jackanory presented an adaptation of The Hobbit in 1979.[28] Unusually for the programme, the adaptation had multiple storytellers. According to one of the narrators David Wood, the release of the production on video has been repeatedly stopped by the Tolkien Estate.[29]

A three-part comic book adaptation with script by Chuck Dixon and Sean Deming and illustrated by David Wenzel was published by Eclipse Comics in 1989. A reprint collected in one volume was released by Del Rey Books in 2001.

Robert Inglis adapted and performed a one-man theatre play of The Hobbit. This performance led to him being asked to read/perform the unabridged audiobook for The Lord of the Rings for Recorded Books in 1990. In 1991 he read the unabridged version of The Hobbit for the same company.

In 2001, Marjo Kuusela produced a ballet Hobitti (The Hobbit in Finnish) with music by Aulis Sallinen for the Finnish National Opera.[30]

In 2004 an operatic version of the story was written and had its world premiere in Canada. The score is currently being revised and will have its American premiere in the Spring of 2008 at the Sarasota Opera in Sarasota, Florida.

A live-action film version was announced on 18 December 2007, to be co-produced by MGM and New Line Cinema, and produced by Lord of the Rings director Peter Jackson. Two movies will be filmed. A director has not yet been named. [31]

Games

The Hobbit has been the subject of several board games, including "The Lonely Mountain" (1984), "The Battle of Five Armies" (1984), and "The Hobbit Adventure Boardgame" (1997) all published by Iron Crown Enterprises.

Games Workshop released a "Battle of Five Armies" (2005) tabletop wargame using 10mm figures, based on their Warmaster rules.

Several computer and video games, both official and unofficial, have been based on the story. One of the first was The Hobbit, an award winning (Golden Joystick Award for Strategy Game of the Year 1983) computer game developed in 1982 by Beam Software and published by Melbourne House for most computers available at the time, from the more popular computers such as the ZX Spectrum, and the Commodore 64, through to the Dragon 32 and Oric computers. By arrangement with publishers, a copy of the novel was included with each game sold. Sierra Entertainment published a platform game titled The Hobbit in 2003 for Windows PCs, PlayStation 2, Xbox, and Nintendo GameCube. It was a similar version of which was also published for the Game Boy Advance.

Movie

The Hobbit prequel to Lord of the Rings has been confirmed to start filming two films in 2009 simultaneously, with the first film releasing in 2010 and the second film releasing in 2011. Peter Jackson will be the Executive Producer but no name of a director has been announced. <ref>http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/22312421/

See also

- The Quest of Erebor, Tolkien's backstory for the novel in Unfinished Tales

- English-language editions of The Hobbit

- Early American editions of The Hobbit

- Translations of The Hobbit

References

- ^ "Houghton Mifflin - Children's Books". Houghton Mifflin. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- ^ Auden, W.H (1954-10-31). "The Hero is a Hobbit". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-07-28.

- ^ "Mythopoeic Fantasy Award for Children's Literature". Retrieved 2007-09-29.

[...] honors books for younger readers (from "Young Adults" to picture books for beginning readers), in the tradition of The Hobbit or The Chronicles of Narnia.

- ^ Eaton, Anne T. (1938-03-13). "A Delightfully Imaginative Journey". The New York Times.

- ^ Langford, David (2001). "Lord of the Royalties". SFX magazine. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- ^ a b Matthews, Dorothy. "The Psychological Journey of Bilbo Baggins". A Tolkien Compass. pp. 27–40.

- ^ a b c Hammond, Wayne (1993). J. R. R. Tolkien: A Descriptive Bibliography. New Castle, Delaware: Oak Knoll Press. pp. 15, 18, 21, 48, 54. ISBN 0-938768-42-5.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ The Hobbit sells for £6000, bbc.co.uk, 26/11/04[1]

- ^ Walne, Toby. How to make a killing from first editions Daily Telegraph 21/11/2007[2]

- ^ The Hobbit breaks records at auction bbc.co.uk, 12/07/02[3]

- ^ Anderson, The Annotated Hobbit (1988)

- ^ a b c Carpenter, Humphrey (1977). J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography. London: George Allen & Unwin. OCLC 3046822.

- ^ a b c Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954a). The Fellowship of the Ring. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Prologue. OCLC 9552942.

- ^ Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (2023) [1981]. The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien: Revised and Expanded Edition. New York: Harper Collins. #211, footnote. ISBN 978-0-35-865298-4.

- ^ Anderson, The Annotated Hobbit (1988), Flies and Spiders, note 23

- ^ Anderson, The Annotated Hobbit (1988), 384

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1937). The Hobbit. London: George Allen & Unwin. p. 63.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1951). The Hobbit. London: George Allen & Unwin. p. 63.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. (1966). The Hobbit. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 62. ISBN 0-395-07122-4.

- ^ Anderson, The Annotated Hobbit (1988)

- ^ Christopher Tolkien, The History of Middle-earth

- ^ Carpenter, Humphrey (1977). J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-04-928037-3.

- ^ "Tolkien's Middle-earth: Lesson Plans, Unit Two". Houghton Mifflin. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- ^ Shippey, Tom: Tolkien: Author of the Century, HarperCollins, 2000, p.41

- ^ Carpenter, Humphrey: Tolkien and the Great War, Review, The Times 2003 Tolkien and the Great War, Review, The Times 2003

- ^ ookrags, B[4]

- ^ Anderson, Douglas, The Annotated Hobbit, p.23

- ^ "The Hobbit". Jackanory.

{{cite episode}}: Unknown parameter|serieslink=ignored (|series-link=suggested) (help) Internet Movie Database: Jackanory, "The Hobbit" (1979) - ^ David Woods, website [5]

- ^ "The Hobbit ('Hobitti'), Op.78, Aulis Sallinen". ChesterNovello. Retrieved 2007-12-02.

- ^ http://www.cnn.com/2007/SHOWBIZ/Movies/12/18/film.thehobbit.ap/index.html