Solfège: Difference between revisions

SolfegeNut (talk | contribs) Fixed do solfège - added Romanian to list of Romance languages that use fixed do |

|||

| Line 79: | Line 79: | ||

===Fixed do solfège=== |

===Fixed do solfège=== |

||

In the major [[Romance languages]] ([[Spanish language|Spanish]], [[Portuguese language|Portuguese]], [[French language|French]], [[Italian language|Italian]]), the syllables Do, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, and Si are used to name notes the same way that the letters C, D, E, F, G, A, and B are used to name notes in English. For native speakers of these languages, solfège is simply ''singing the names of the notes'', omitting any modifiers such as 'sharp' or 'flat' in order to preserve the rhythm. This system is called '''fixed do''' and is widely used in [[Spain]], [[Portugal]], [[France]], [[Italy]], [[Belgium]], and [[Latin America]]n countries, as well as countries such as [[Greece]], [[Iran]] and [[Japan]] where non-Romance languages predominate. |

In the major [[Romance languages]] ([[Spanish language|Spanish]], [[Portuguese language|Portuguese]], [[French language|French]], [[Italian language|Italian]], [[Romanian_language|Romanian]]), the syllables Do, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, and Si are used to name notes the same way that the letters C, D, E, F, G, A, and B are used to name notes in English. For native speakers of these languages, solfège is simply ''singing the names of the notes'', omitting any modifiers such as 'sharp' or 'flat' in order to preserve the rhythm. This system is called '''fixed do''' and is widely used in [[Spain]], [[Portugal]], [[France]], [[Italy]], [[Belgium]], and [[Latin America]]n countries, as well as countries such as [[Greece]], [[Iran]] and [[Japan]] where non-Romance languages predominate. |

||

[[Image:French keyboard.png|right|250px|thumb|The names of the notes in French.]] |

[[Image:French keyboard.png|right|250px|thumb|The names of the notes in French.]] |

||

Revision as of 20:56, 14 November 2008

In music, solfège (Template:PronEng, also called solfeggio, sol-fa, or solfa) is a pedagogical solmization technique for the teaching of sight-singing in which each note of the score is sung to a special syllable, called a solfège syllable (or "sol-fa syllable"). The seven syllables normally used for this practice in English-speaking countries are: do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, and ti (with a chromatic scale of ascending di, ri, fi, si, li and descending te, le, se, me, ra).

Traditionally, solfège is taught in a series of exercises of gradually increasing difficulty, each of which is also known as a "solfège". By extension, the word "solfège" may be used of an instrumental étude. Solfege is taught at many conservatories of music. For example, in the 1960s The Juilliard School hired the now late, well-known solfege expert Renee Longy to teach solfege to many instrumentalists and singers.

Etymology

French "solfège" and Italian "solfeggio" ultimately derive from the names of two of the syllables used: so[l] and fa. The English equivalent of this expression, "sol-fa", is also used, especially as a verb[citation needed] ("to sol-fa" a passage is to sing it in solfège).

The word "solmization" derives from the Medieval Latin "solmisatiō", ultimately from the names of the syllables sol and mi. "Solmization" is often used synonymously with "solfège", but is technically a more generic term[1]; i.e., solfège is one type of solmization (albeit a nearly universal one in Europe and the Americas).

Origin of the solfège syllables

The use of a seven-note diatonic musical scale is ancient, though originally it was played in descending order.

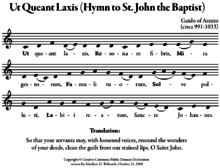

In the eleventh century, the music theorist Guido of Arezzo developed a six-note ascending scale that went as follows: ut, re, mi, fa, sol, and la. A seventh note, "si" was added shortly after.[2] The notes were taken from the first verse of a Latin hymn[3] below (where the sounds fell on the scale), and later "ut" and "sol" were changed to flow with the other notes, while "si" was changed to "ti" to avoid confusion with "so[l]".

Ut queant laxis resonāre fibris

Mira gestorum famuli tuorum,

Solve polluti labii reatum,

Sancte Iohannes.

The hymn (The Hymn of St. John) was written by Paulus Diaconus in the 8th century. It translates[4] as:

So that these your servants can, with all their voice, to sing your wonderful feats, clean the blemish of our spotted lips. O Saint John!

An alternative theory on the origins of solfège proposes that it may have also had Arabic musical origins. It has been argued that the solfège syllables (do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, ti) may have been derived from the syllables of the Arabic solmization system Durr-i-Mufassal ("Separated Pearls") (dal, ra, mim, fa, sad, lam) during the Islamic contributions to Medieval Europe. This origin theory was first proposed by Meninski in his Thesaurus Linguarum Orientalum (1680) and then by Laborde in his Essai sur la Musique Ancienne et Moderne (1780).[5][6]

Descending scales

The descending major (diatonic) scale:

- high doh ('Do) High Doh' (The apostrophe indicates high Doh)

- tee (Ti) Tee - "The Piercing Tone"

- lah (La) Lah - "The Sad Tone"

- soh (Sol) Soh - "The Bright Tone"

- fah (Fa) Fah - "The Desolate Tone"

- mee (Mi) Mee - "The Calm Tone"

- ray (Re) Ray - "The Hopeful Tone"

- doh (Do) Doh - "The Strong Tone"

The descending chromatic scale:

- Hi doh (Do) Doh'

- tee (Ti) Tee

- tay (Te) Tay

- lah (La) Lah

- lay (Le) Lay

- soh (Sol) Soh

- say (Se) Say

- fah (Fa) Fah

- mee (Mi) Mee

- may (Me) May

- ray (Re) Ray

- rah (Ra) Rah

- doh (Do) Doh

French scholars Laborde and Villoteau suggest that Guido of Arezzo was himself influenced by Muslim musical notation.[7]

| Arabic letters | ﻡ mīm | ﻑ fāʼ | ﺹ ṣād | ﻝ lām | ﺱ sīn | ﺩ dāl | ﺭ rāʼ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Musical Notes | mi | fa | sol | la | si | do | re |

In Romance countries, these seven syllables have come to be used to name the notes of the scale, instead of the letters C, D, E, F, G, A and B. (For example, they would say, "Beethoven's ninth symphony is in Re minor".) This is also the case in Japan. In Germanic countries, the letters are used for this purpose, and the solfège syllables are encountered only for their use in sight-singing and ear training. (They would say, "Beethoven's ninth symphony is in D minor".)

In Anglo-Saxon countries, "sol" is often changed to "so", and "si" was changed to "ti" by Sarah Glover in the nineteenth century so that every syllable might begin with a different letter. "So" and "ti" are used in tonic sol-fa and in the song "Do-Re-Mi".

The modern use of solfège

There are two main types of solfège:

- Fixed do, in which each syllable corresponds to a note-name. This is analogous to the Romance system naming pitches after the solfège syllables, and is used in Romance and Slavic countries, among others.

- Movable do, or solfa, in which each syllable corresponds to a scale degree. This is analogous to the Guidonian practice of giving each degree of the hexachord a solfège name, and is mostly used in Germanic countries.

Fixed do solfège

In the major Romance languages (Spanish, Portuguese, French, Italian, Romanian), the syllables Do, Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, and Si are used to name notes the same way that the letters C, D, E, F, G, A, and B are used to name notes in English. For native speakers of these languages, solfège is simply singing the names of the notes, omitting any modifiers such as 'sharp' or 'flat' in order to preserve the rhythm. This system is called fixed do and is widely used in Spain, Portugal, France, Italy, Belgium, and Latin American countries, as well as countries such as Greece, Iran and Japan where non-Romance languages predominate.

| Note name (English) | Note name (Romance languages) | Fixed do solfège syllable | Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|---|

| C | Do, Ut (French) | do | /do/ |

| C♯ | Do♯, Ut♯ (French) | ||

| D♭ | Re♭ | re | /re/ |

| D | Re | ||

| D♯ | Re♯ | ||

| E♭ | Mi♭ | mi | /mi/ |

| E | Mi | ||

| F | Fa | fa | /fa/ |

| F♯ | Fa♯ | ||

| G♭ | Sol♭ | sol | /sol/ |

| G | Sol | ||

| G♯ | Sol♯ | ||

| A♭ | La♭ | la | /la/ |

| A | La | ||

| A♯ | La♯ | ||

| B♭ | Si♭ | si | /si/ |

| B | Si |

The pattern shown above also applies to the less common sharps and flats (E♯, B♯, C♭, F♭) and to the double-sharps and double-flats: Accidentals do not affect the syllables used. There are no altered syllables.

In comparison to the movable do system, this system of sight-reading is advocated for the development of strong relative pitch in its users[citation needed]. This is a controversial subject among music educators in schools in the United States. While movable do is easier to teach and learn, fixed do promises strong sight-readers because students learn the relationships between specific pitches rather than just the way intervals function. Instrumentalists who begin sight-singing for the first time in college as music majors find fixed do to be the system more consistent with the way they learned to read music. In other, much rarer cases in which a singer using fixed do has perfect pitch or very strong relative pitch, sight-reading transposing instruments can be very difficult.

For choirs, sight-singing fixed do is more suitable than sight-singing movable do for reading atonal music, polytonal music, pandiatonic music, music that modulates or changes key often, or music in which the composer simply did not bother to write a key signature. It is not uncommon for this to be the case in modern or contemporary choral works. Choirs that have learned to read fixed do will have an advantage in reading music by composers such as Arnold Schoenberg, Eric Whitacre, or Ivan Hrušovský more easily and fluently than otherwise.

Movable do solfège

Movable do is frequently employed in Australia, Ireland, the UK, the USA and English-speaking Canada (although many American conservatories use French-style fixed do). Originally it was used throughout continental Europe as well, but in the mid-nineteenth century was phased out by fixed do.[citation needed] In the movable do system, each solfège syllable corresponds not to a pitch, but to a scale degree: The first degree of a major scale is always sung as 'do', the second as 're', etc. (For minor keys, see below.) In movable do, a given tune is therefore always sol-faed on the same syllables, no matter what key it is in.

The solfège syllables used for movable do differ slightly from those used for fixed do, because the English variants of the basic syllables ('so' instead of 'sol' and 'ti' instead of 'si') are usually used, and chromatically altered syllables are usually included as well:

| Major scale degree | Movable do solfège syllable | Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Do | /doʊ/ |

| Raised 1 | Di | /diː/ |

| Lowered 2 | Ra | /rɑː/ |

| 2 | Re | /reɪ/ |

| Raised 2 | Ri | /riː/ |

| Lowered 3 | Me (or Ma) | /meɪ/ (/mɑː/) |

| 3 | Mi | /miː/ |

| 4 | Fa | /fɑː/ |

| Raised 4 | Fi | /fiː/ |

| Lowered 5 | Se | /seɪ/ |

| 5 | So | /soʊ/ |

| Raised 5 | Si | /siː/ |

| Lowered 6 | Le (or Lo) | /leɪ/ (/loʊ/) |

| 6 | La | /lɑː/ |

| Raised 6 | Li | /liː/ |

| Lowered 7 | Te (or Ta) | /teɪ/ (/tɑː/) |

| 7 | Ti | /tiː/ |

If, at a certain point, the key of a piece modulates, then it is necessary to change the solfège syllables at that point. For example, if a piece begins in C major, then C is initially sung on "do", D on "re", etc.. If, however, the piece then modulates to G, then G is sung on “Do”, A on “re”, etc., and C is then sung on “fa".

Passages in a minor key may be sol-faed in one of two ways in movable do: either starting on do (using "me", "le", and "te" for the lowered third, sixth, and seventh degrees, and "la" and "ti" for the raised sixth and seventh degrees), or starting on la (using "fi" and "si" for the raised sixth and seventh degrees). The latter is sometimes preferred in choral singing, especially with children.

| Natural minor scale degree | Movable do solfège syllable (La-based minor) | Movable do solfège syllable (Do-based minor) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | La | Do |

| Raised 1 | Li | Di |

| Lowered 2 | Te (or Ta) | Ra |

| 2 | Ti | Re |

| 3 | Do | Me (or Ma) |

| Raised 3 | Di | Mi |

| 4 | Re | Fa |

| Raised 4 | Ri | Fi |

| Lowered 5 | Me (or Ma) | Se |

| 5 | Mi | So |

| 6 | Fa | Le (or Lo) |

| Raised 6 | Fi | La |

| 7 | So | Te (or Ta) |

| Raised 7 | Si | Ti |

One particularly important variant of movable do, but differing in some respects from the system here described, was invented in the nineteenth century by John Curwen, and is known as tonic sol-fa.

In Italy, in 1972, Roberto Goitre wrote the famous method "Cantar leggendo", which has come to be used for choruses and for music for young children.

Solfège in popular culture

- Woody Guthrie's song Do-Re-Mi uses the term as a slang word for "money", rather than musical method.

- Do-Re-Mi is a song featured in the musical The Sound of Music. Within the story, Maria uses the song to teach the notes of the major musical scale to the Von Trapp children, by identifying six of the solfège syllables, Do Re Mi Fa So and Ti with the English words "doe", "ray", "me", "far", "sew" and "tea"; La is called "a note to follow So". Each syllable of the diatonic scale appears as solfège in its lyrics, sung on the pitch it names.

- The Music Man used solfège in its music, especially in Shipoopi.

- A Japanese animated series with a musical theme is known as Ojamajo Doremi, with the English language version known as Magical DoReMi. In the Japanese series it is about a girl named Doremi and two of her friends, but the dub changed their names to Dorie, Reanne, and Mirabelle. In the original, Doremi's name was to reflect solfège, but in the English version, the first syllables of all their names together make solfège. In the episode "Dustin' the Old Rusty Broom", when they make over the Rusty Broom, they call it the DoReMi Magic Shop, naming it after the first syllables of their names. Patina complains that it's her shop, but Dorie says, "We were going to call it DoReMiPa, but that wouldn't sound right." The fairies in said show are known as Dodo, Rae Rae (Rere in the Japanese version), Mimi, and so forth, all given to reflect solfège as well.

- Hawkwind named their 1972 album Doremi Fasol Latido.

- The Curwen hand signals are used in the climactic scene of the film Close Encounters of the Third Kind when François Truffaut's character communicates with the alien being.

- Solfeggio was the name of a song used in a comedy sketch featuring The Nairobi Trio on Ernie Kovacs's television show. The lyrics of the song featured the solfège tones and was played while three cast members dressed in trench coats, gorilla masks and bowler hats engaged in silly situations on-screen. Among Kovacs' celebrity friends both Jack Lemmon and Frank Sinatra are known to have performed in the skit. Seated at screen right at a piano was a female simian (often Kovacs' wife, Edie Adams), robotically thumping the keys. "Solfeggio" was written by Robert Maxwell and sung by the Ray Charles Singers.

- The Aristocats has a section that is a music lesson with scales and arpeggios in French.

- A song by The Enright House, on their album "A Maze and Amazement", is entitled "Do Re Mi" (a tribute to the American opera singer, Brenda Roberts).

- The Greek entry for the Eurovision Song Contest 1977, "Mathima Solfege", is about a solfège lesson.

- The Japanese rock band Asian Kung-Fu Generation released an album titled Sol-fa.

- The Kokiri, a fictional elf-like race from the Legend of Zelda game series who are largely named after blends of solfège tones.

- A group of genetically enhanced individuals teach their friend to speak properly, who was mute up until then because of problems with her genetic enhancement, in Star Trek: Deep Space Nine by singing the scale and teaching it to her.

- The American jazz clarinettist Irving Fazola (1912-1949) took his last name from "fa", "so", and "la". Born Irving Prestopnik, he was given the nickname "Fazola" as a child because of his musical abilities.

- The sung libretto to Philip Glass's Einstein on the Beach is entirely in numbers and fixed do solfege syllables.

- Composer Karl Jenkins used solfège in his 1997 album Adiemus II in the song Chorale VI

- The California punk rock band NOFX parodied the solfege-inspired song from the Sound of Music in Bleeding Heart Disease, the fourth track off of their 1996 album Heavy Petting Zoo.

References

- ^ solmization - Definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary

- ^ Davies, Norman (1997), Europe, pp.271-2

- ^ The American Heritage of the English Language. 1976.

- ^ Cgregorian chant - Translation & scores for diverse festivities

- ^ (Farmer 1988, pp. 72–82)

- ^ Miller, Samuel D. (Autumn 1973), "Guido d'Arezzo: Medieval Musician and Educator", Journal of Research in Music Education, 21 (3): 239–45

- ^ "The Arab Contribution to Music of the Western World" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-01-06.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); line feed character in|title=at position 10 (help) - ^ "The Arab Contribution to Music of the Western World" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-01-06.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); line feed character in|title=at position 10 (help)

See also

- Solresol, a constructed language that had the solfège notes as syllables and could be sung or played as well as spoken.

- Vocable

- Sargam

External links

- History of Notation by Neil V. Hawes

- Various scales with their solfège names and associated hand signs

- A search engine for melodies that uses solfège

- An online music notation editor for Sargam, the Indian solfège

- Music theory online: key signatures and accidentals

- Music theory online : staffs, clefs & pitch notation

- GNU Solfège, a free software program to study solfeggio

- Eyes and Ears, an anthology of melodies for practicing sight-singing, available under a Creative Commons license