Black Madonna: Difference between revisions

m Date maintenance tags and general fixes |

K kokkinos (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 150: | Line 150: | ||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

* [[Black Madonna of Częstochowa]] |

* [[Black Madonna of Częstochowa]] |

||

* [[Kālī|Kali]] |

|||

* [[Theotokos of Vladimir]] |

* [[Theotokos of Vladimir]] |

||

* [[Mariology]] |

* [[Mariology]] |

||

Revision as of 13:44, 12 October 2009

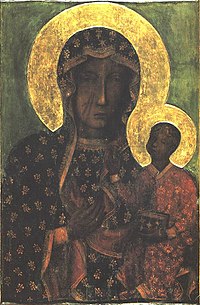

A Black Madonna or Black Virgin is a statue or painting of Mary in which she is depicted with dark or black skin, especially those created in Europe in the medieval period or earlier. In this specialized sense "Black Madonna" does not apply to images of the Virgin Mary portrayed as explicitly black African, which are popular in Africa and areas with large black populations, such as the United States.

Some statues get their color from the material used, such as ebony or other dark wood, but there is debate about whether this choice of material is significant. Others were originally light-skinned but have become darkened over time, for example by candle soot. This is generally thought to be the explanation for most medieval "black" images of Mary, but this theory has been contested by those who believe that the color of originally-dark Madonnas had some esoteric significance.

The Black Madonnas are generally found in Catholic areas. The statues are mostly wooden but occasionally stone, often painted and up to 75 cm tall, generally dating from between the 11th and 15th centuries. They fall into two main groups: free-standing upright figures and seated figures on a throne. The pictures are usually icons which are Byzantine in style, often made in 13th or 14th century Italy. Their faces tend to have recognizably European features. There are about 450-500 Black Madonnas in Europe, depending on how they are classified. There are at least 180 Vierges Noires in France, and there are hundreds of non-medieval copies as well. Some are in museums, but most are in churches or shrines and are venerated by devotees. A few are associated with miracles and attract substantial numbers of pilgrims.

Theories about the Black Madonnas

Most theologians and historians believe that most examples of dark coloring can be accounted for by the natural color of the wood used or by changes in color over time. They may add that a pale alabaster face was a post-medieval development. A counter-argument points to the apparently bright colors of the clothing on some images with painted black face and hands.

Interest in studying Black Madonnas revived in the late 20th century. Some scholars of comparative religion, particularly those with Afrocentrist, feminist, or neo-pagan backgrounds, have suggested that Black Madonnas are descendants of pre-Christian mother or earth goddesses (Moss, Benko), often highlighting Isis as the key ancestor-goddess (Redd, McKinney-Johnson). Some psychologists have discussed maternal and female archetypes, often from a Jungian perspective, as well as themes of feminine power, as they find them expressed in the Black Madonnas (Gustafson, Begg). Although these approaches have stimulated some academic interest, they do not represent the well-established consensus about medieval motives for carving or painting Black Madonnas.

A link between the Black Madonnas of the European Middle Ages and ancient pagan traditions and representations has been asserted typologically despite the absence of evidence of any direct historical or artistic influences. Although no direct Catholic theological sources exist, it has also been suggested by some authors that the medieval veneration of Black Madonnas was in response to a line from the Song of Songs 1:5 in the Old Testament: "I am black but comely, O daughters of Jerusalem, ..." These words are discussed at length in the sermons of St Bernard of Clairvaux, although he uses them to refer not to Mary but to the Catholic Church[1]. Several surviving Black Madonnas are inscribed with these words, although in at least some cases the inscriptions were added at a later date.

Those writers who present esoteric interpretations of the Black Madonnas usually include some combination of the following elements:

- Some claim that Black Madonnas grew out of pre-Christian earth goddess traditions. Their dark skin may be associated with ancient images of these goddesses, and with the color of fertile earth. They are sometimes associated with stories of being found by chance in a natural setting: in a tree or by a spring, for example. It is further asserted that some of their Christian shrines are located on the sites of earlier temples to Cybele and Diana of Ephesus.

- Some claim that Black Madonnas derive from the Egyptian goddess Isis. The dark skin may echo an African archetypal mother figure. Professor Stephen Benko claims that early Christian pictures of a seated mother and child were influenced by images of Isis and Horus. He further asserts that the slashes on the cheek of the Black Madonna of Częstochowa represent the markings of the Eye of Horus.

- Some claim that the Black Madonnas portray the original skin tone of the Virgin Mary, thus placing the figures in apt historical contexts, as Jesus' family was more likely than not to have Semitic colors and features.

- Some claim that Black Madonnas express a feminine power that is not fully conveyed by a pale-skinned Mary, whom they assert symbolizes gentler qualities like obedience and purity. The "feminine power" approach is sometimes linked to female sexuality, which was allegedly repressed by the medieval Church.

- Some claim an association between Black Madonnas, the Templars and St. Bernard of Clairvaux. Ean Begg suggests they were revered by an esoteric cult with Templar and Cathar links, but this idea is dismissed by most historians, who also reject stories of connections with Mary Magdalene, and Gnosticism.

Black Madonnas Worldwide

Europe

Belgium

- Onze-Lieve-Vrouw van Regula (Moeder van Regula van Spaignen), Brugge

- Chapelle de la Vierge Noire, Maillen (Assesse)

- Our Lady of Flanders, Tournai

- Gothic Church of Our Lady, Halle

Croatia

- Marija Bistrica

- Donji Kraljevec, County of Medjumurje

France

Many examples exist, including:

- Aix-en-Provence: in Cathédrale Saint-Sauveur d'Aix

- Arbois, Jura

- Arceau, Côte-d'Or

- Arconsat, Puy-de-Dôme

- Aurillac, Cantal [2]

- Avioth, Meuse

- Chartres, Eure-et-Loir: crypt of the Cathedral of Chartres [3]

- Clermont-Ferrand, Puy de Dôme [4]

- Guingamp, Brittany, Basilica of Notre Dame de Bon Secour.

- La Chapelle-Geneste, Haute-Loire [5]

- Le Puy-en-Velay, Haute-Loire [6][7][8]

- Marseille: Saint Victor

- Mauriac, Cantal [9]

- Meymac, Corrèze [10]

- Myans, Savoie

- Menton, Eglise de St. Michel

- Rocamadour: Our Lady of Rocamadour [11]

- Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, Alpes Maritimes

- Tarascon, Bouches-du-Rhône: Notre-Dame du Château [12]

- Thuret, Puy-du-Dome [13]

Germany

Ireland

Italy

- Our Lady of Tindari, Sicily

- Black Madonna of Oropa, Piedmont

- Our Lady of Crea, Casale Monferrato, Alessandria. In the hillside Sanctuary at Crea (Santuario di Crea), a cedar-wood figure, said to be one of three Black Virgins brought to Italy from the Holy Land c345 by St. Eusebius.

- Madonna della Salute, Santa Maria della Salute, Venice

- Madonna di Canneto, Canneto Valley near Settefrati, Province of Frosinone, Lazio

- "La Madonna del Soccorso" (The Madonna of Succor), St. Severinus Abbot and Saint Severus Bishop Faeto, Province of Foggia in the Puglia Region. The Madonna is in San Severo, Puglia, a statue in gold garments, object of a major 3 day festival that attracts over 350,000 people to this small town. The infant Jesus is white.

- Madonna di Viggiano, Basilicata

- Madonna di Castelmonte (Prepotto), Province of Udine, in Friuli Venezia Giulia

Luxembourg

- Our Lady in Esch-sur-Sure, Luxembourg

- The black Madonna in Luxembourg-Grund, Luxembourg-City

Lithuania

- Ausros Vartai, The Gates of Dawn, St Theresa's Vilnius, Lithuania

Malta

- In Malta a medieval painting of a Black Madonna rests in a small church in Hamrun, with the church being possibly the oldest one in the area, originally built in honor of St. Nicholas. Brought to Malta by a merchant in the year 1630, the painting is of a statue found in Atocha, a parish in Madrid, Spain, and is widely known as Il-Madonna tas-Samra. (This can mean 'tanned Madonna', 'brown Madonna', or 'Madonna of Samaria'). She may also be called Madonna ta' Atoċja, corresponding to the Spanish Nuestra Señora de Atocha. There were celebrations in 2005, the painting's 375th year in Malta.

Poland

Portugal

- Nossa Senhora da Nazaré, Nazaré

Russia

Kosovo

- Church of the Black Madonna, Letnice

Spain

- Our Lady of Watkin, Coria, Cáceres

- Our Lady Of Atocha, Madrid

- Our Lady of Guadalupe, Santa María de Guadalupe, Cáceres

- Our Lady of la Cabeza, Andújar, Jaén

- The Virgin of Candelaria, Tenerife, Canary Islands

- Virgin of la Encina, Ponferrada, León

- Nuestra Señora de la Merced (Our Lady Of Mercy), Jerez de la Frontera, Cádiz

- The Virgin of the Miracles (Virgen de los milagros), El Puerto de Santa María, Cádiz

- Virgin of Montserrat in Catalonia

- Virgen de la Peña de Francia (The Virgin of France's Rock), Salamanca

- The Virgin of Regla, Chipiona, Cádiz

- Our Lady of Torreciudad, Torreciudad, Huesca

- Virgen Morena (Dark Virgin), statue of La Esclavitud de Nuestra Señora del Sagrario in the Cathedral of Toledo (The Enslavement of Our Lady of the Tabernacle)

- Lluc Monastery (Mallorca)

Switzerland

- Our Lady of the Hermits, Einsiedeln

- Santa Maria Loretana, Sonogno (Valle Verzasca)

the Americas

Brazil

Chile

- La Virgen Morena of Andacollo

Costa Rica

Trinidad and Tobago

- La Divina Pastora, Siparia

United States

Asia

the Philippines

- Nuestra Señora de la Paz y Buen Viaje de Antipolo, Antipolo, Rizal

- Nuestra Señora de Guia, Ermita, Manila

In fiction

A Black Madonna is an important motif in The Secret Life of Bees by Sue Monk Kidd. She inspires spiritual strength in the female characters in the novel, and has been connected with "the solidarity of the divine mother with those who are oppressed", according to Jennie S. Knight. This Madonna is not of the specific European kind discussed above.

See also

References

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (July 2009) |

This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (May 2009) |

- Begg, Ean The Cult of the Black Virgin (1985)

- Benko, Stephen Virgin Goddess: Studies in the Pagan and Christian Roots of Mariology (1993)

- Chiavola Birnbaum, Lucia Black Madonnas: Feminism, Religion, and Politics in Italy (2000)

- Gustafson, Fred The Black Madonna (1990)

- Gustafson, Fred The black madonna of Einsiedeln : a psychological perspective (1975)

- Hale, Susan Elizabeth Sacred Space, Sacred Sound: The Acoustic Mysteries of Holy Places Quest Books (2007) ISBN 0835608565

- Knight, Jennie S Remythologizing the Divine Feminine in Religion and Popular Culture in America ed. Forbes and Mahan (University of California, 2005)

- LeMieux, Raymond W. The Black Madonnas of France (1991)

- McKinney-Johnson, Eloise Egypt's Isis: the Original Black Madonna in Black Women in Antiquity (Journal of African Civilizations ; V. 6) edited by Ivan van Sertima

- Moser, Mary Beth Honoring darkness: exploring the power of black madonnas in Italy (2005)

- Moss, Leonard In Quest of the Black Virgin: She Is Black Because She Is Black in Mother Worship:Themes and Variations (1982) edited by James Preston

- Redd, Danita Black madonnas of Europe: diffusion of the African Isis in Black Women in Antiquity (Journal of African Civilizations ; V. 6) edited by Ivan van Sertima

- Ralls, Karen Knights Templar Encyclopedia, Career Press (2007) ISBN 1564149269

- Scheer, Monique From Majesty to Mystery: Change in the Meanings of Black Madonnas from the: Sixteenth to Nineteenth Centuries. The American Historical Review 107.5 (2002)

- Schmid, Margrit Rosa Schwarz bin ich und schön ([SJW] Schweizerisches Jugendschriftenwerk 2002)

- Schmid, Margrit Rosa Die Wallfahrt zur schwarzen Madonna Documentary film, 30 minutes (Margrit R. Schmid Zurich 2003)

External links

- ^ St. Bernard of Clairvaux, "Sermon 25 on the Song of Songs: Why the Bride is Black but Beautiful"[1]

- ^ "Black Virgin of Aurillac". Web.archive.org. 2007-12-19. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ "Photos from France: On the Trail with Susan G. Butruille". Aracnet.com. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ "Notre Dame de Clermont". Web.archive.org. 2007-12-19. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ "Notre Dame de La Chapelle Geneste". Web.archive.org. 2007-08-23. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ "Photos from France: On the Trail with Susan G. Butruille". Aracnet.com. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ "Notre Dame du Puy, Cathedrale...: Photo by Photographer Dennis Aubrey". photo.net. 2007-11-09. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ "Photos from France: On the Trail with Susan G. Butruille". Aracnet.com. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ "Black Virgin of Mauriac". Web.archive.org. 2007-12-19. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ "Notre Dame de Meymac". Web.archive.org. 2007-08-07. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ "Photos from France: On the Trail with Susan G. Butruille". Aracnet.com. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ "Notre Dame du Chateau". Web.archive.org. 2007-12-19. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- ^ "Vierge des Croisades". Web.archive.org. 2007-12-19. Retrieved 2009-07-25.

- Index of Black Madonnas

- Black Virgin Sites in France

- Black Madonnas - Michael P. Duricy

- Black Madonnas and other Mysteries of Mary - Ella Rozett

- The Black Virgin - Karen Ralls

- Montserrat

- Pilgrimage

- Travels in France with the Dark Madonna

- Jasna Góra Monastery

- Black Madonna gallery by Canon Jim Irvine, New Brunswick, Canada

- The Black Madonna "The work of God"

- Nuestra Señora de Atocha

- Black Madonna Pilgrimage to Central France

- Black Madonna photo collection on Flickr