2010 Canterbury earthquake: Difference between revisions

Fattyjwoods (talk | contribs) |

|||

| Line 79: | Line 79: | ||

[[File:2010 canterbury aftershocks by depth.svg|right]] |

[[File:2010 canterbury aftershocks by depth.svg|right]] |

||

===Aftershocks=== |

===Aftershocks=== |

||

{{As of|2010|09|06|df=yes}}, |

{{As of|2010|09|06|df=yes}}, around 270 [[aftershock]]s have been recorded, including three of [[Moment magnitude scale|5.4 magnitude]]. Some have caused further damage, ruining buildings in the [[central business district]].<ref>{{cite news|urlhttp://www.stuff.co.nz/national/canterbury-earthquake/4105730/Quake-Canterbury-shaken-by-270-aftershocks|title=Caterbury shaken by 240 aftershocks|Publisher=Stuff.co.nz </ref><ref name="MG">{{cite news |url=http://www.montrealgazette.com/news/Aftershocks+hampering+repairs+Zealand/3486422/story.html |title=Aftershocks hampering repairs in New Zealand |first1=Gyles |last1=Beckford |author2=[[Reuters]] |newspaper=[[Montreal Gazette]] |date=6 September 2010 |accessdate=6 September 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.3news.co.nz/Quake-updates-Aftershocks-continue-to-rumble/tabid/423/articleID/174433/Default.aspx |title=Quake updates: Aftershocks continue to rumble |author1=[[3 News]] |author2=[[Radio Live]] |author3=[[New Zealand Press Association]] |publisher=3 News ([[MediaWorks New Zealand]]) |date=6 September 2010 |accessdate=6 September 2010}}</ref> [[GNS Science]] has not ruled out a shock of magnitude 6, which was previously expected.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.3news.co.nz/Canterbury-should-brace-for-big-aftershock/tabid/423/articleID/174582/Default.aspx |title=Canterbury should brace for big aftershock |author=[[New Zealand Press Association]] |publisher=[[3 News]] ([[MediaWorks New Zealand]]) |date=6 September 2010 |accessdate=6 September 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.stuff.co.nz/national/4094986/Massive-7-4-quake-hits-South-Island |title=Weather the next threat after earthquake |work=''[[Stuff.co.nz]]'' |publisher=[[Fairfax New Zealand]] |date=4 September 2010 |accessdate=6 September 2010}}</ref> Aftershocks could be felt as far away as [[Timaru]].<ref name="NZHlatest">{{cite web |url=http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=10671050 |title=Latest news: Christchurch earthquake |newspaper=[[The New Zealand Herald]] |date=5 September 2010 |accessdate=6 September 2010}}</ref> On {{Nowrap|8 September 2010}}, Christchurch experienced a large 5.1 aftershock with an epicentre just 7 km from the city centre.<ref name="GeoNet2">{{cite web |

||

|title = New Zealand earthquake report - Sep 8, 2010 at {{Nowrap|7:49 am}} (NZST) |

|title = New Zealand earthquake report - Sep 8, 2010 at {{Nowrap|7:49 am}} (NZST) |

||

|work=GeoNet |

|work=GeoNet |

||

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

|date=8 September 2010 |

|date=8 September 2010 |

||

|accessdate=8 September 2010}}</ref> |

|accessdate=8 September 2010}}</ref> |

||

{{-}}. While the 5.1M aftershock was not as large on the richter scale as others, which had been up to 5.4M, the relative nearness and nature of the shock, being short and sharp, produced more damage and concern than previous aftershocks had. |

|||

==Casualties, damage and other effects== |

==Casualties, damage and other effects== |

||

Revision as of 04:17, 8 September 2010

This article documents a current event. Information may change rapidly as the event progresses, and initial news reports may be unreliable. The latest updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. (September 2010) |

| |

| UTC time | ?? |

|---|---|

| Magnitude | 7.1 Mw[1][2] |

| Depth | 10 km (6.2 mi)[2] |

| Epicenter | 43°33′S 172°11′E / 43.55°S 172.18°E, near Darfield, Canterbury, New Zealand |

| Areas affected | |

| Max. intensity | MM 9[3] |

| Casualties | 1 death due to heart attack,

2 seriously injured, Approximately 100 total injuries[4] |

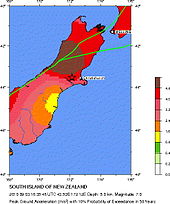

The 2010 Canterbury earthquake (also known as the Darfield earthquake[5] and the Christchurch earthquake) was a 7.1 magnitude earthquake,[1][2] which struck the South Island of New Zealand at 4:35 am on 4 September 2010 local time (16:35 3 September UTC).[1] It caused widespread damage and several power outages, particularly in the city of Christchurch.[4][6] Two residents were seriously injured, one by a falling chimney and a second by flying glass.[4][7] One person died of a heart attack suffered during the quake, although this could not be directly linked to the earthquake.[4][7] Mass fatalities were avoided partly due to New Zealand's strict building codes, although this was also aided by the quake occurring during the night when most people were asleep at home.[8][9]

The earthquake's epicentre was 40 kilometres (25 mi) west of Christchurch,[5] near the town of Darfield. The hypocentre was at a shallow[5] depth of 10 km.[1] A foreshock of roughly magnitude 5.8 hit five seconds before the main quake,[10] and strong aftershocks have been reported,[4][11] up to magnitude 5.4.[12] The initial quake lasted about 40 seconds,[6] and was felt widely across the South Island, and in the North Island as far north as New Plymouth.[13] As the epicentre was on land away from the coast, no tsunami occurred.[5]

The National Crisis Management Centre in the basement of the Beehive in Wellington was activated, and Civil Defence declared a state of emergency for Christchurch, the Selwyn District, and the Waimakariri District[14] while Selwyn District, Waimakariri and Timaru activated their emergency operation centres.[15] A curfew was established for parts of Christchurch Central City from 7:00 pm to 7:00 am in response to the earthquake.[7] The New Zealand Army was deployed to the worst affected areas within Canterbury.

Geological background

In the first eighty years of European settlement in Christchurch (1850-1930) four earthquakes caused significant damage; the last of them the 1922 Motunau earthquake.[16] Modelling conducted for the New Zealand Earthquake Commission in 1991 found that earthquakes with a Mercalli intensity of VIII (significant property damage, loss of life possible) could recur on average in the Christchuch area every 55 years. The study also highlighted the dangers of soil liquefaction of the alluvial sediments underlying the city, and the likelihood of significant damage to water, sewer and power supply services.[17]

About 100 faults and fault segments have been recognised around the region, some as close as 20 km to central Christchurch. The closest faults to Christchurch capable of producing powerful earthquakes are found in the Rangiora-Cust area, near Hororata, and near Darfield.[18] However, the 2010 quake occurred on a previously unknown fault. Scientists are investigating whether the main 2010 quake may have actually been two or three almost simultaneous earthquakes.[10]

The main quake occurred as a result of strike-slip faulting within the crust of the Pacific plate, near the eastern foothills of the Southern Alps at the western edge of the Canterbury Plains.[19] The earthquake epicentre is located about 80–90 km (50–56 mi) to the south and east of the current surface expression of the Australia–Pacific plate boundary through the island (the Alpine and Hope Faults).[19] Though removed from the plate boundary itself, the earthquake likely reflects right-lateral motion on one of a number of regional faults related to the overall relative motion of these plates and may be related to the overall southern propagation of the Marlborough Fault System in recent geologic time.[19]

Aftershocks

As of 6 September 2010[update], around 270 aftershocks have been recorded, including three of 5.4 magnitude. Some have caused further damage, ruining buildings in the central business district.[20][21][22] GNS Science has not ruled out a shock of magnitude 6, which was previously expected.[23][24] Aftershocks could be felt as far away as Timaru.[25] On 8 September 2010, Christchurch experienced a large 5.1 aftershock with an epicentre just 7 km from the city centre.[26]

Casualties, damage and other effects

Most of the damage was in the area surrounding the epicentre, including the city of Christchurch, New Zealand's second-largest urban area with a population of 386,000. Minor damage was reported as far away as Dunedin and Nelson, both around 300–350 kilometres (190–220 mi) from the earthquake's epicentre.[27]

The total cost of damages has been estimated to be as high as NZ$2 billion[4] (1.8 percent of New Zealand's gross domestic product).

Two Christchurch residents were seriously injured, one by a falling chimney and a second by flying glass, and many suffered less serious injuries.[4][7] One person died of a heart attack suffered during the quake, but doctors could not determine whether this was caused by the earthquake.[4][7]

Effects in Christchurch

Sewers were damaged,[28] and water lines were broken. The water supply at Rolleston, located in the southwest of Christchurch, was contaminated. Power to up to 75 percent of the city was disrupted.[29] Christchurch Hospital was forced to use emergency generators in the immediate aftermath of the quake.[29] About 90% of the electricity in Christchurch had been restored by 6:00pm the day of the earthquake. The repair of electricity was estimated to be more difficult in the rural areas.[30] One building caught fire after its electricity was turned back on, igniting leaking LPG in the building. The fire was quickly extinguished by the Fire Service before it could spread.[31]

Damage to buried pipes has allowed sewage to contaminate the residential water supply. Residents have been warned to boil tap water before using it for brushing teeth, drinking, and washing or cooking food. Several cases of gastroenteritis have been reported.[32][33] On 7 September, 28 cases had been observed at the city's welfare centres alone.[34]

Christchurch International Airport was closed following the earthquake and flights in and out of it cancelled. It reopened at 1:30 pm, following inspection of the terminals and main runway.[35]

All schools and early childhood centres in Christchurch City, Selwyn and Waimakariri Districts were ordered shut until Monday 13 September for health and safety assessments.[36] The city's two universities, the University of Canterbury and Lincoln University were also closed until 13 September awaiting health and safety assessments.[37][38]

Crime in Christchurch decreased 11 percent compared to the previous year following the earthquake, although there were initial reports of looting in the city centre and "known criminals" trying to pass off as council workers to get into the central city cordon area. Police also observed a 53 percent jump in the rates of domestic violence following the earthquake.[39]

Reports of the quake's intensity in Christchurch generally ranged from IV to VIII (moderate to destructive) on the modified Mercalli scale.[27]

A record number of babies for a Saturday were born at Christchurch Women's Hospital in the 24 hours after the quake, with the first baby arriving ten minutes after the initial shock.[40]

Effects outside Christchurch

The quake's epicentre was around Darfield, around 40 kilometres (25 mi) from Christchurch.[41] Four metres (13 ft) of sideways movement has been measured between the two sides of the previously unknown fault.[10]

In many towns outside Christchurch, the electrical grid was disrupted, with it taking an estimated two days to fully restore power to those affected.[42][43] Power outage was reported as far away as Dunedin.[44]

A 5 km (3.1 mi) section of rail track was damaged near Kaiapoi and there was lesser track damage at Rolleston and near Belfast.[45] As a precaution, state rail operator KiwiRail shut down the entire South Island rail network after the earthquake, halting some 15 trains. After inspection, services south of Dunedin and north of Kaikoura recommenced at 10:30 am.[46] The Main South Line, linking Christchurch with Dunedin, was given the all-clear and reopened just after 6:00 pm to allow emergency aid, including 300,000 litres (70,000 imp gal; 80,000 US gal) of drinking water, to be railed into Christchurch.[47]

Major bridges on State Highways and the Lyttelton road tunnel were inspected by the New Zealand Transport Agency, and found to be in structurally sound condition. The only major road closure outside Christchurch was a slip in the Rakaia Gorge, blocking State Highway 77. The slip was partially cleared by 4:00 pm to allow a single lane of traffic through the site.[48][49]

The quake caused damage to historic buildings in Lyttelton, Christchurch's port town, including cracks in a church and the destruction of parts of a hotel.[41] The Akaroa area of Banks Peninsula came through the earthquake relatively unscathed, though there was some damage to the town's war memorial and some homes were extensively damaged. Duvauchelle Hotel was also seriously affected.[50]

In Oamaru, 225 kilometres southwest of Christchurch, the earthquake caused part of a chimney on the St Kevin's College principal's residence to fall through the house, and caused the clock atop the Waitaki District Council building to stop at 4:36am. The earthquake also caused the Dunedin Town Hall clock and the University of Otago clocktower to stop working in Dunedin, some 350 km away from the quake epicentre.[51]

The earthquake was a wake-up call to many New Zealand residents. Two Dunedin supermarkets sold out of bottled water following the earthquake as people stocked up on emergency supplies.[51]

Major stores across the South Island were affected as their distribution centres in Christchurch were closed. Both The Warehouse[52]and Progressive Enterprises (owners of Countdown)[53], which have their sole South Island distribution centres in Christchurch, had to ship essential products to their South Island stores from the North Island, while Foodstuffs (owners of New World and Pak'n Save) had to ship to all their South Island stores from their Dunedin distribution centre.[54]

Notable buildings

Many of the most badly-affected structures in both Christchurch and the surrounding districts were older buildings, including several notable landmarks. New Zealand Historic Places Trust board member Anna Crighton said the earthquake had been "unbelievably destructive." The historic homesteads of Hororata and Homebush inland from Christchurch were both extensively damaged, as were Ohinetahi homestead and Godley House on Banks Peninsula.[55] Homebush, located at Glentunnel only 15 kilometres from the earthquake's epicentre, was the historic home of the Deans family, one of the Canterbury Region's pioneer settler families, but was so extensively damaged that it has been described as being "practically in ruins".[56]

The 1911 Anglican church of St. John in Hororata, five kilometres south of Glentunnel, was extensively damaged when part of its tower collapsed.[57] The port town of Lyttelton's most notable building, the 1876 Timeball station, was also damaged in the earthquake, though strengthening work completed in 2005 may have saved it from further damage.[55]

Many of Christchurch's major landmarks survived intact, including the Canterbury Provincial Chambers, the Anglican cathedral, and Christ's College.[58] The Catholic Cathedral of the Blessed Sacrament also survived largely unscathed, though windows were broken at the Catholic basilica. The central city's iconic Christchurch Press building also survived with only minor damage, as did the city's International Antarctic Centre and Christchurch Art Gallery, the latter of which served as the Civil Defence Headquarters during the earthquake aftermath.[50]

Christchurch Arts Centre, housed in the former Canterbury College buildings, was less fortunate, with moderate damage to the Great Hall, the Clocktower, and the Observatory.[55] Within Christchurch the 1881 Oxford Terrace Baptist Church[59] was extensively damaged, and the city's Repertory Theatre, on Kilmore Street in the central city, was also extensively damaged and may be beyond repair.[60] Several other Christchurch area churches have suffered serious damage, including St. Mary's Anglican church in Merivale, St. John's Anglican church in Latimer Square, and the Rugby Street Methodist church.[61]

Several notable buildings in the Timaru area, 160 km southwest of Christchurch, were also badly affected. A pinnacle on the tower of St Mary's Anglican Church tower fell to the ground, and the recently-restored tower itself sustained "significant cracking".[62] The spire of St. Joseph's Catholic Church in Temuka was also shifted 10 cm by the earthquake, leaving it precariously balanced, and the town's historic Royal Hotel was also damaged.[63]

Liquefaction

A feature of the quake was the widespread damage caused by soil liquefaction. This was particularly the case in the eastern suburbs, Avonside and Kaiapoi[64], with over 100 houses in the new suburb of Bexley[65] rendered uninhabitable by silt and subsidence. While the problem had been long well understood by planners[66][67][68], its not clear that the public understood it as well, or that it significantly influenced development, buying or building decisions.

Emergency response and relief efforts

A state of emergency was declared at 10:16 am on 4 September for the city, and the city's central business district was closed to the general public.[69] Some looting was reported shortly after the quake, and a curfew was put in place from 7:00 pm to 7:00 am.[7] The New Zealand Army was deployed to help the police enforce the closure and curfew.

A Royal New Zealand Air Force C-130 Hercules plane brought 42 urban search and rescue personnel and three sniffer dogs from the North Island to Christchurch the day of the quake,[70] to help check for people buried in the rubble and determine which buildings are safe to use.[71] There are a large number of police and engineers present in the disaster areas. The New Zealand Army may deploy personnel upon the request of the Christchurch mayor.[42] Eighty police officers from Auckland were dispatched to Christchurch to assist with general duties there.[72]

The United Nations has contacted the New Zealand government and offered its assistance, and is being informed and kept up to date of the situation in the South Island.[73][74] The Salvation Army also set up a donation fund for the earthquake.[75]

Prime Minister John Key, who was raised in Christchurch, visited the scene of the devastation within hours of the earthquake. Christchurch mayor Bob Parker requested that the Prime Minister order the deployment of the New Zealand Army to keep stability and to assist in searches when possible within Christchurch, and the Prime Minister stated that the Army was on standby.[76] New Zealand's Earthquake Commission, which provides government natural disaster insurance, will be assisting by paying out on claims from residential property owners for damage caused by the earthquake.[77]

'Welfare centres' were set up with the help of Red Cross, The Salvation Army and St. John Ambulance at Burnside High School, Linwood College and Addington Raceway, where over 244 people slept on the night after the quake.[78][79][80][81] Tankers delivered drinking water to the welfare centres.[82][83]

Relative lack of casualties

The media have remarked on the lack of casualties, despite the close parallels of the quake to incidents that have had devastating consequences in other countries. The analysis especially compared the Canterbury quake with the 2010 Haiti earthquake, which also occurred in similar proximity to an urban area, also occurred at shallow depth under the surface, and was of very similar strength. Unlike many tens of thousands of deaths in Haiti (with some estimates placing the death toll at one in ten or higher), no deaths directly attributable to the earthquake were reported in New Zealand.[84] This was ascribed to that fact that the quake happened in the early hours of a Saturday morning, when most people were asleep[9] in timber framed homes, and "...there would almost certainly have been many deaths and serious injuries had it happened during a busy time of the day...".[85] Another important factor was building practices which took earthquakes into account, starting after the 1848 Marlborough earthquake and the 1855 Wairarapa earthquake, both of which badly affected Wellington.[84] These led to formal standards after the 1931 Hawke's Bay earthquake,[86][87] which have since been progressively updated.[88] By contrast, Haiti's much lower standard codes were poorly enforced.[89] Ground shaking in populated areas of Canterbury was also generally less strong than for the Haiti quake.[90][91]

Media coverage

TV One interrupted their daily schedule to bring special all day One News coverage of the earthquake,[92] as well as an extended 90 minute 6 o'clock news bulletin. Radio New Zealand National interrupted their Saturday morning programming to bring a special edition of their morning news programme Morning Report,[93] which normally only airs on weekdays. This was followed up with a Midday Report half-hour special. Newstalk ZB also interrupted regular programming nationwide and broadcast on all Radio Network stations in the Canterbury region as it was a Civil Defence emergency.[94] The earthquake made headlines in the Sydney Morning Herald, BBC News,[95] the Guardian, NDTV, Sky News, CNN,[96] Fox News and MSNBC.[97]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d "New Zealand earthquake report - Sep 4, 2010 at 4:35 am (NZST)". GeoNet. Earthquake Commission and GNS Science. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ a b c "Magnitude 7.0 - South Island of New Zealand: Details". United States Geological Survey. 3 September 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ^ "New Zealand earthquake report - Sep 4 2010 at 4:35 am (NZST) - Quake Maps". GeoNet. Earthquake Commission and GNS Science. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Massive 7.4 quake hits South Island". Stuff.co.nz. 3 September 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Sep 4, 2010 - Darfield earthquake damages Canterbury". GeoNet. Earthquake Commission and GNS Science. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ a b "Strong earthquake rocks New Zealand's South Island". BBC News. 3 September 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f "Officers flown into protect Christchurch". Stuff.co.nz. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "Strict codes behind 'miracle'". Singapore: AFP - The Straits Times. 5 September 2010. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ^ a b NZPA. "Why so few casualties in Canterbury quake?". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved Accessed 4 September 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ a b c NZPA (4 September 2010). "Canterbury earthquake really three quakes?". stuff.co.nz.

- ^ "New Zealand Earthquake 2010: Strong Quake Shakes Christchurch". The Huffington Post. 3 September 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ^ "New Zealand Earthquake Report - Sep 4 2010 at 4:55 pm (NZST)". GeoNet. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ Van Der Heide, Maike (4 September 2010). "Marlborough, Kaikoura escape worst of quake". The Marlborough Express. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "State of emergency declared in Canterbury". Radio New Zealand. September 4, 2010. Retrieved September 4, 2010.948

- ^ "Latest updates: Canterbury earthquake | National News". Tvnz.co.nz. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ http://adsabs.harvard.edu/full/1999GeoJI.139..769D

- ^ Elder, D.M.G. (1991). The earthquake hazard in Christchurch: a detailed evaluation (Report). Earthquake Commission. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Christchurch riddled with quake fault zones | Otago Daily Times Online News Keep Up to Date Local, National New Zealand & International News". Odt.co.nz. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ^ a b c "Magnitude 7.0 - South Island of New Zealand: Summary". United States Geological Survey. 3 September 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ^ {{cite news|urlhttp://www.stuff.co.nz/national/canterbury-earthquake/4105730/Quake-Canterbury-shaken-by-270-aftershocks|title=Caterbury shaken by 240 aftershocks|Publisher=Stuff.co.nz

- ^ Beckford, Gyles; Reuters (6 September 2010). "Aftershocks hampering repairs in New Zealand". Montreal Gazette. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

{{cite news}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - ^ 3 News; Radio Live; New Zealand Press Association (6 September 2010). "Quake updates: Aftershocks continue to rumble". 3 News (MediaWorks New Zealand). Retrieved 6 September 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ New Zealand Press Association (6 September 2010). "Canterbury should brace for big aftershock". 3 News (MediaWorks New Zealand). Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ^ "Weather the next threat after earthquake". Stuff.co.nz. Fairfax New Zealand. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ "Latest news: Christchurch earthquake". The New Zealand Herald. 5 September 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ^ "New Zealand earthquake report - Sep 8, 2010 at 7:49 am (NZST)". GeoNet. Earthquake Commission and GNS Science. 8 September 2010. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ^ a b "New Zealand earthquake report - Sep 4, 2010 at 4:35 am (NZST): Shaking maps". GeoNet. Earthquake Commission and GNS Science. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "New Zealand Quake Victims Say 'It was terrifying'". The Epoch Times. 3 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ a b "New Zealand's South Island Rocked by Magnitude 7.0 Earthquake". Bloomberg. 3 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ Updated at 10:03pm on 4 September 2010. "Radio New Zealand : News : Christchurch Earthquake : Day of shocks leaves dozens homeless in Christchurch". Radionz.co.nz. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Fire danger as power restored after quake - tvnz.co.nz". Television New Zealand. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "Polluted water biggest risk to health - medic". The Press. 7 September 2010. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ^ "Earthquake: Inquiry into gastro outbreak". New Zealand Herald. 6 September 2010. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ^ "Day four, counting the toll - live updates - tvnz.co.nz". Television New Zealand. 7 September 2010. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ^ "State of emergency declared, airport reopens". TVNZ. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "Ministry of Education - Canterbury earthquake information". 7 September 2010. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ^ "University of Canterbury". University of Canterbury. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "Lincoln University". Lincoln University. 5 September 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- ^ "Crime down but family violence up in Chch". Television New Zealand. 7 September 2010. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ^ "Oh baby: quake shakes NZ mums into labour". ABC News. 6 September 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ^ a b "Quake timeline". Stuff.co.nz. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ a b "Latest News: Christchurch earthquake". Nzherald.co.nz. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ Washington Saldías (3 September 2010). "Terremoto al sur de Nueva Zelanda" (in Spanish). Pichilemu News. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "Magnitude 7.1 earthquake hits Chch". TVNZ. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "Christchurch quake: What's working and what's not". The New Zealand Herald. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "Key services being restored after Canterbury earthquake - tvnz.co.nz". Television New Zealand. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "Canterbury quake: As it happened - tvnz.co.nz". Television New Zealand. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "State highway network update - Canterbury". New Zealand Transport Agency. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "Highways escape major damage - tvnz.co.nz". Television New Zealand. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ a b "Christchurch earthquake update", Spice News, 7 September 2010. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ^ a b "Canterbury earthquake: in brief". Otago Daily Times. Monday 6 September 2010. p. 6.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Christchurch Earthquake - The Warehouse". 8 September 2010. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ^ "Christchurch earthquake updates - Countdown". 6 September 2010. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ^ "Christchurch Earthquake staff update". 5 September 2010. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ^ a b c Van Beynen, M. "Quake devastates Christchurch heritage", stuff.co.nz, 5 September 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- ^ "Quake destroys historic homestead", nzherald.co.nz, 5 September 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- ^ Stewart, C. "Christchurch in lockdown amid aftershocks", theaustralian.com.au, 5 September 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- ^ "Christchurch landmark buildings mostly unscathed", nz.news.yahoo.com, 5 September 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ^ Reported as an 1882 structure in some media; the Church's website [1] states 1881 construction

- ^ "Night curfew for quake ravaged Chch", tvnz.co.nz, 5 September 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- ^ "Canterbury's heritage churches hammered in earthquake", Episcopal life online, 8 September 2010. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ^ Bailey, E. "Damage closes Timaru churches", Timaru Herald, 6 September 2010. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ^ Historic Temuka pub damaged by quake", New Zealand Herald, 4 September 2010. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ^ [2]

- ^ "They're going to bulldoze the whole street", NZ Herald

- ^ "The Solid Facts on Christchurch Liquefaction", ECAN website

- ^ "Regional Liquefaction Study for Waimakariri District", Society for Earthquake Engineering website

- ^ "Pegasus Town Infrastructure Geotechnical Investigations..." , www.waimakariri.govt.nz

- ^ "Latest news: Christchurch earthquake". New Zealand Herald. 5 September 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- ^ "Royal New Zealand Air Force Assets Assisting Christchurch". voxy.co.nz. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ^ "Christchurch CBD to stay closed off as aftershocks continue". Radio New Zealand. 5 September 2010. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- ^ "Latest updates: Canterbury earthquake". TVNZ.co.nz. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "Latest earthquake news". Nzherald.co.nz. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "Christchurch hit by 7.1 quake". Gisborne Herald. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ^ "Donating to the Christchurch earthquake". TVNZ.co.nz. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "Army wanted in Quake-ravaged Canterbury". Stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ Tait, Maggie (4 September 2010). "NZ quake bill could hit $NZ2bn". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "Christchurch Earthquake – General Update Sunday 6am" (Press release). Christchurch City Council. 5 September 2010. Archived from the original on 5 September 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ^ "7.1 earthquake: Govt gives $5 million". Stuff.co.nz. Fairfax New Zealand. 6 September 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help) - ^ Dickison, Michael (6 September 2010). "Hundreds turn up at shelters to get a little sleep". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ^ ONE News (5 September 2010). "Cantabrians told to get homes checked". Television New Zealand. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ^ "Curfew continues in shaken Christchurch". The New Zealand Herald. 5 September 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ^ "Latest News from the Christchurch earthquake". The Star Canterbury. 6 September 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ^ a b Bojanowski, Axel (4 September 2010). "Naturgewalt in Neuseeland - Warum die Menschen dem Beben entkamen". The Spiegel Online (in German). Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "Darfield earthquake damages Canterbury", GeoNet, New Zealand

- ^ "Building for earthquake resistance", Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand

- ^ "Achieving Safety Through Standards–75 Years After The Hawkes Bay Earthquake", standards.govt.nz

- ^ "Earthquake-prone buildings", Department of Building and Housing

- ^ Walsh, Bryan (16 January 2010) "After the Destruction: What Will It Take to Rebuild Haiti?" "Haiti had some of the worst buildings in world...", Time (magazine), Accessed 5 September 2010

- ^ "PAGER - M 7.0 - SOUTH ISLAND OF NEW ZEALAND - Alert Version 7". Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ^ "PAGER - M 7.0 - HAITI REGION - Alert Version 9". Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ^ "ONE News live from Christchurch throughout the day". TVNZ. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "Morning Report Special". Radio New Zealand. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "New Zealand's premier source of news and information". Newstalk ZB. 2007-05-08. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ^ "BBC News - New Zealand police declare curfew after earthquake". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ^ "No deaths reported after powerful quake strikes New Zealand". CNN.com. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ Johnson, Alex (4 September 2010). "Crews search for people trapped in New Zealand rubble". MSNBC. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

External links

- Canterbury Earthquake, information from government and other support agencies

- Environment Canterbury

- Christchurch City Council

- Seismograph Drums - McQueens Valley (MQZ), Canterbury, New Zealand (closest seismograph to most aftershocks)

- Canterbury earthquake from GNS Science