Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial: Difference between revisions

m →Sculptor and stone choice: Fixed ref tag markup error |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

| locmapin = District of Columbia |

| locmapin = District of Columbia |

||

| area = 4 acres (16,000 m<sup>2</sup>) |

| area = 4 acres (16,000 m<sup>2</sup>) |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| built = 2011 |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| architecture= |

| architecture= |

||

| visitation_num = |

| visitation_num = |

||

Revision as of 13:57, 11 October 2011

Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial | |

| File:Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial Stone of Hope at Dusk.jpg The Stone of Hope | |

| Location | 1964 Independence Ave. SW, Washington D.C. (Official Website: http://www.mlkmemorial.org) |

|---|---|

| Area | 4 acres (16,000 m2) |

| Built | by ALEC(Swag) |

| Architect | ROMA Design Group (Architects) Ed Jackson, Jr. (executive architect) Lei Yixin (sculptor) |

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial is located in West Potomac Park in Washington, D.C., southwest of the National Mall (but within the larger area commonly referred to as the "National Mall").[1] The Memorial is America's 395th unit of the National Park System[2] and is located at the northwest corner of the Tidal Basin near the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial, on a sightline linking the Lincoln Memorial to the northwest and the Jefferson Memorial to the southeast. The official address of the monument, 1964 Independence Avenue, S.W., commemorates the year that the Civil Rights Act of 1964 became law.[3]

Covering four acres, the memorial opened to the public on August 22, 2011, after more than two decades of planning, fund-raising and construction.[4][5] A ceremony dedicating the Memorial was scheduled for Sunday, August 28, 2011, the 48th anniversary of the "I Have a Dream" speech that Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in 1963[6] but has been postponed until October 16 (the 16th anniversary of the 1995 Million Man March on the National Mall) due to Hurricane Irene.[7][8][9]

Although this is not the first memorial to an African-American in Washington, D.C., Dr. King is the first African-American honored with a memorial on or near the National Mall and only the fourth non-President to be memorialized in such a way. The King Memorial is administered by the National Park Service (NPS).

Martin Luther King, Jr.

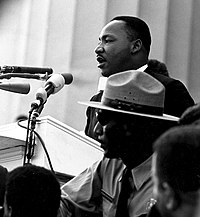

Martin Luther King, Jr. (January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American clergyman, activist, and prominent leader in the African-American Civil Rights Movement.[10] He is best known for being an iconic figure in the advancement of civil rights in the United States and around the world, using nonviolent methods following the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi.[11] King is often presented as a heroic leader in the history of modern American liberalism.[12]

A Baptist minister, King became a civil rights activist early in his career.[13] He led the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott and helped found the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in 1957, serving as its first president. King's efforts led to the 1963 March on Washington, where King delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech. There, he expanded American values to include the vision of a color blind society, and established his reputation as one of the greatest orators in American history.[14]

In 1964, King became the youngest person to receive the Nobel Peace Prize for his work to end racial segregation and racial discrimination through civil disobedience and other nonviolent means.[14] By the time of his death in 1968, he had refocused his efforts on ending poverty and stopping the Vietnam War.[15][16]

King was assassinated on April 4, 1968, in Memphis, Tennessee.[14] His assassination led to a nationwide wave of race riots in Washington D.C., Chicago, Baltimore, Louisville, Kentucky, Kansas City, and dozens of other cities.[17] He was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1977 and Congressional Gold Medal in 2004; Martin Luther King, Jr. Day was established as a U.S. federal holiday in 1986, and was first observed in all states in 2000.[18][19][20]

Other memorials to King

A bust of King was added to the "gallery of notables" in the United States Capitol in 1986, portraying him in a "restful, nonspeaking pose."[21] Numerous other memorials honor him around the world, including:[22]

- The Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. Church in Debrecen, Hungary

- The King-Luthuli Transformation Center in Johannesburg, South Africa

- The Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. Forest in Israel's Southern Galilee region (along with the Coretta Scott King Forest in Biriya Forest, Israel)

- The Martin Luther King, Jr. School in Accra, Ghana

- The Gandhi-King Plaza (garden), at the India International Center in New Delhi, India

Memorial vision statement

The official vision statement for the memorial notes:

Dr. King championed a movement that draws fully from the deep well of America's potential for freedom, opportunity, and justice. His vision of America is captured in his message of hope and possibility for a future anchored in dignity, sensitivity, and mutual respect; a message that challenges each of us to recognize that America's true strength lies in its diversity of talents. The vision of a memorial in honor of Martin Luther King, Jr. is one that captures the essence of his message, a message in which he so eloquently affirms the commanding tenants of the American Dream – Freedom, Democracy and Opportunity for All; a noble quest that gained him the Nobel Peace Prize and one that continues to influence people and societies throughout the world. Upon reflection, we are reminded that Dr. King's lifelong dedication to the idea of achieving human dignity through global relationships of well being has served to instill a broader and deeper sense of duty within each of us— a duty to be both responsible citizens and conscientious stewards of freedom and democracy.[23]

Harry E. Johnson, the President and Chief Executive Officer of the memorial foundation, added these words in a letter posted on the memorial's website:

The King Memorial is envisioned as a quiet and peaceful space. Yet drawing from Dr. King's speeches and using his own rich language, the King Memorial will almost certainly change the heart of every person who visits. Against the backdrop of the Lincoln Memorial, with stunning views of the Tidal Basin and the Jefferson Memorial, the Memorial will be a public sanctuary where future generations of Americans, regardless of race, religion, gender, ethnicity or sexual orientation, can come to honor Dr. King.[24]

Project history

The memorial is a result of an early effort of Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Incorporated to erect a monument to King.[25] King was a member of the fraternity, initiated into the organization via Sigma Chapter on June 22, 1952,[26] while he was attending Boston University.[27] King remained involved with the fraternity after the completion of his studies, including delivering the keynote speech at the fraternity's 50th anniversary banquet in 1956.[27] In 1968, after King's assassination, Alpha Phi Alpha proposed erecting a permanent memorial to King in Washington, D.C. The fraternity's efforts gained momentum in 1986, after King's birthday was designated a national holiday.[28]

In 1996, the United States Congress authorized the Secretary of the Interior to permit Alpha Phi Alpha to establish a memorial on Department of Interior lands in the District of Columbia, giving the fraternity until November 2003 to raise $100 million and break ground. In 1998, Congress authorized the fraternity to establish a foundation—the Washington, D.C. Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial Project Foundation—to manage the memorial's fundraising and design, and approved the building of the memorial on the National Mall. In 1999, the United States Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) and the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) approved the site location for the memorial.

The memorial's design, by ROMA Design Group, a San Francisco-based architecture firm, was selected out of 900 candidates from 52 countries. On December 4, 2000, a marble and bronze plaque was laid by Alpha Phi Alpha to dedicate the site where the memorial will be built.[29] Soon thereafter, a full-time fundraising team began the fundraising and promotional campaign for the memorial. A ceremonial groundbreaking for the memorial was held on November 13, 2006, in West Potomac Park.

In August 2008, the foundation's leaders estimated the memorial would take 20 months to complete with a total cost of $120 million USD.[30] As of December 2008, the foundation had raised approximately $108 million,[31] including substantial contributions from such donors as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation,[30] The Walt Disney Company Foundation, the National Association of Realtors,[32] and filmmaker George Lucas. The figure also includes $10 million in matching funds provided by the United States Congress.

In October 2009, the memorial's final project was approved by federal agencies and a building permit was issued.[33] Construction began in December 2009[34] and was expected to take 20 months to complete.[35] The foundation conducted a press tour on December 1, 2010, as the "Stone of Hope" was nearing completion. At that time only $108 million of the $120 million project cost had been raised but saved $8 million by having the memorial made in China.[36]

Location and structure

The street address for the memorial is 1964 Independence Ave., SW, Washington, DC, with "1964" chosen as a direct reference to the 1964 Civil Rights Act, a milestone in the Civil Rights movement in which King played an important role.[37] The memorial is located on a 4-acre (1.6 ha) site in West Potomac Park that borders the Tidal Basin, southwest of the National Mall.[3] The memorial is near the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial and is intended to create a visual "line of leadership" from the Lincoln Memorial, on whose steps King gave his "I Have a Dream" speech at the March on Washington, to the Jefferson Memorial.[3][6]

|

"Out of a mountain of despair, From "I have a dream" speech, |

The centerpiece for the memorial is based on a line from King's "I Have A Dream" speech: "Out of a mountain of despair, a stone of hope."[38] A 30 feet (9.1 m)-high relief of King named the “Stone of Hope” stands past two other pieces of granite that symbolize the "mountain of despair."[38] Visitors literally "pass through" the Mountain of Despair on the way to the Stone of Hope, symbolically "moving through the struggle as Dr. King did during his life."[39]

A 450 feet (140 m)-long inscription wall includes excerpts from many of King's sermons and speeches.[5] On this crescent-shaped granite wall, fourteen of King's quotes will be inscribed, the earliest from the time of the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott in Alabama, and the latest from his final sermon, delivered in 1968 at Washington, D.C.'s National Cathedral, just four days before his assassination.[39]

The memorial includes 24 niches (semicircular nave-like shapes) along the upper walkway to commemorate the contribution of the many individuals that gave their lives in different ways to the civil rights movement – from Medgar Evers to the four children murdered in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham.[40] A number of the niches are left open and incomplete, allowing additional niches to be dedicated as new individuals are honored.[40]

The relief of King is intended to give the impression that he is looking over the Tidal Basin at the Jefferson Memorial, and that the cherry trees that "adorn the site" will bloom every year during the anniversary of King's death.[41]

This memorial is not be the first one in the nation's capital to honor an African-American, because one already exists for Mary McLeod Bethune, founder of the National Council of Negro Women, who also served as an unofficial advisor to President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[42] A 17 feet (5.2 m)-tall bronze statue of her is located in Lincoln Park, East Capitol St. and 12th St., NE.[42] However, this will be the first memorial to an African-American on or near the National Mall.[42]

The memorial is the fourth that commemorates an individual who never served as President of the United States that is located on or near the National Mall.[43] The others include the George Mason Memorial, honoring George Mason, author of the Virginia Declaration of Rights (the basis for the U.S. Constitution's Bill of Rights, near the Thomas Jefferson Memorial; the John Ericsson Memorial, erected to honor John Ericsson,[44] the Swedish-born engineer and inventor who designed the USS Monitor during the Civil War; and the John Paul Jones Memorial, erected in 1912 near the Tidal Basin in memory of John Paul Jones, the Scottish-born American naval hero who served during the American Revolution.[43][45]

-

Stone of Hope

-

Mountain of Despair

-

One inscription from Inscription Wall

-

Photo from across the Tidal Basin

-

"Stone of Hope," memorial centerpiece

-

Lei Yixin signature on the "Stone of Hope"

Inscriptions

The Inscription Wall

Fourteen quotes from King's speeches, sermons, and writings are inscribed on the Inscription Wall.[46] The "Council of Historians" created to choose the quotations included Dr. Maya Angelou, Lerone Bennett, Dr. Clayborne Carson, Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Marianne Williamson and others,[47][48] although the claim has been made that not everyone on the Council attended the meetings.[49] According to the official National Park Service brochure for the Memorial, the inscriptions that were chosen "stress four primary messages of Dr. King: justice, democracy, hope, and love."[50]

The earliest quote is from 1955, spoken during the time of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, and the latest is from a sermon King delivered at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C., four days before he was assassinated.[51] The quotes are not arranged in chronological order, so that no visitor must follow a "defined path" to follow the quotations, instead being able to start reading at any point he or she might choose.[51] Because the main theme of the Memorial is linked to King's famous "I Have a Dream" speech, none of the quotations on the Inscription Wall come from that speech.[51]

The selection of quotes was announced at a special event at the National Museum on February 9, 2007 (at the same time the identity of the sculptor was revealed).[52] The fourteen quotes on the Inscription Wall are:[46]

- "We shall overcome because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice." (16 August 1967, Atlanta, GA)

- "Darkness cannot drive out darkness, only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate, only love can do that." (1963, Strength to Love)

- "I believe that unarmed truth and unconditional love will have the final word in reality. This is why right, temporarily defeated, is stronger than evil triumphant." (10 December 1964, Oslo, Norway)

- "Make a career of humanity. Commit yourself to the noble struggle for equal rights. You will make a greater person of yourself, a greater nation of your country, and a finer world to live in." (18 April 1959, Washington, DC)

- "I oppose the war in Vietnam because I love America. I speak out against it not in anger but with anxiety and sorrow in my heart, and above all with a passionate desire to see our beloved country stand as a moral example of the world." (25 February 1967, Los Angeles, CA)

- "If we are to have peace on earth, our loyalties must become ecumenical rather than sectional. Our loyalties must transcend our race, our tribe, our class, and our nation; and this means we must develop a world perspective." (24 December 1967, Atlanta, GA)

- "Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly." (16 April 1963, Birmingham, AL)

- "I have the audacity to believe that peoples everywhere can have three meals a day for their bodies, education and culture for their minds, and dignity, equality and freedom for their spirits." (10 December 1964, Oslo, Norway)

- "It is not enough to say "We must not wage war." It is necessary to love peace and sacrifice for it. We must concentrate not merely on the negative expulsion of war, but on the positive affirmation of peace." (24 December 1967, Atlanta, GA)

- "The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy." (25 February 1967, Los Angeles, CA)

- "Every nation must now develop an overriding loyalty to mankind as a whole in order to preserve the best in their individual societies." (4 April 1967, Riverside Church, New York, NY)

- "We are determined here in Montgomery to work and fight until justice runs "down like water, and righteousness like a mighty stream." (5 December 1955, Montgomery, AL)

- "We must come to see that the end we seek is a society at peace with itself, a society that can live with its conscience." (16 April 1963, Birmingham, AL)

- "True peace is not merely the absence of tension: it is the presence of justice." (16 April 1963, Birmingham, AL)

Some of King's words reflected in these quotations are based on other sources, including the Bible, and in one case—"the arc of the moral universe" quote—upon the words of Theodore Parker, an abolitionist and Unitarian minister, who died shortly before the beginning of the Civil War.[53]

Inscriptions on the Stone of Hope

In addition to the fourteen quotations on the Inscription Wall, each side of the Stone of Hope includes an additional statement supposedly attributed to King.[49] The first, from the "I Have a Dream" speech, is "Out of the Mountain of Despair, a Stone of Hope"—the quotation that serves as the basis for the monument's design.[49] However, the words on the other side of the stone—"I Was a Drum Major for Justice, Peace, and Righteousness"—are not a direct quote, but instead a shortened and paraphrased version of a statement included in a 1968 sermon that critics say seriously change its meaning and do a disservice to King's memory.[49] The inscription has become a controversy that began with statements by Maya Angelou,[49] followed up by other spoken and written statements including a September 2, 2011 editorial published by The Washington Post recommending that the wording be changed.[54]

Artists

Artists involved in the construction of the memorial include:[55]

- Devraux and Purnell/ROMA Design Group Joint Ventures

- McKissack and McKissack/Turner Construction Company/Tompkins Builders, Inc./Gilford Corporation Joint Ventures

- Master Lei Yixin, sculptor

- Nicholas Benson, calligrapher

Dedication

The memorial opened to visitors before the actual dedication, with visiting hours on Monday-Thursday, August 22–25, 2011.[56] The official dedication was initally scheduled to have taken place at 11 am Sunday August 28. The dedication was to follow a pre-dedication concert at 10 am.[5] A post-dedication concert was scheduled for 2 pm.[5] However, on August 25, the event's organizers postponed most Saturday and Sunday activities because of safety concerns related to Hurricane Irene, which was expected to impact the Washington area during the weekend.[57][58][59] The organizers subsequently rescheduled the dedication to October 16, 2011, the 16th anniversary of the 1995 Million Man March on the National Mall.[8][9]

Before the event's postponement, President Barack Obama was expected to deliver remarks at the dedication ceremony. Aretha Franklin and Stevie Wonder were scheduled to perform.[60] Many other individuals were also expected to participate in the event, including members of the King family; civil rights leaders John Lewis, Jesse Jackson, and Andrew Young; actor Jamie Foxx; and filmmaker George Lucas.[60] As many as 250,000 people were predicted to attend the dedication.[60]

In addition to the August 28 ceremony and concerts, an interfaith prayer service was scheduled to take place at the Washington National Cathedral on August 27, as well as a day-long youth event and gala/pre-dedication dinner at the Washington DC Convention Center, also on the 27th.[60] However, the prayer service was moved to the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in northeast Washington after the 2011 Virginia earthquake damaged the Cathedral on August 23.[61]

Administration

The National Park Service administers the memorial and is responsible for ongoing operation and maintenance.[62] Bob Vogel, superintendent of the National Mall an Memorial Parks said that:

“From World War II to Vietnam Veterans, from Lincoln to Jefferson and now to King, the memorials and monuments along the National Mall are where millions of visitors every year learn about our history. The National Park Service is honored to serve as the keeper of America’s story, and with this new memorial, to have this incredible venue from which to share the courage of one man and the struggle for civil rights that he led.[2]

Controversy

Fees to King family

In 2001, the foundation's efforts to build the memorial were stalled because Intellectual Properties Management Inc., an organization operated by King's family, wanted the foundation to pay licensing fees to use his name and likeness in marketing campaigns. The memorial's foundation, beset by delays and a languid pace of donations, stated that "the last thing it needs is to pay an onerous fee to the King family." Joseph Lowery, past president of the King-founded Southern Christian Leadership Conference stated in the The Washington Post, "If nobody's going to make money off of it, why should anyone get a fee?"[63] Cambridge University historian David Garrow, who won a Pulitzer Prize for his biography of King, said of King's family's behavior, "One would think any family would be so thrilled to have their forefather celebrated and memorialized in D.C. that it would never dawn on them to ask for a penny." He added that King would have been "absolutely scandalized by the profiteering behavior of his children."[64] The family pledged that any money derived would go back to the King Center's charitable efforts.[33][65]

The foundation has paid various fees to the King family's Intellectual Properties Management Inc., including a management fee of $71,700 in 2003.[66] In 2009, the Associated Press revealed that the King family had negotiated an $800,000 licensing deal with the foundation for the use of King's words and image in fundraising materials for the memorial.[67]

Conflicts between federal agencies

Further delay was encountered in 2008, due to a disagreement between the three federal agencies that must approve the memorial. The memorial design that was approved by the CFA and the NCPC was not approved by the NPS, due to security concerns. The NPS insisted upon the inclusion of a barrier that would prevent a vehicle from crashing into the memorial area. However, when the original design was submitted to the other two agencies, including such a barrier, the CFA and the NCPC rejected the barrier as being restrictive in nature, which would run counter to King's philosophy of freedom and openness.[68] Eventually, a compromise was reached, which involved the use of landscaping to make the security barriers appear less intrusive upon the area.[69] The compromise plan was approved in October 2009,[69] clearing the way for construction of the memorial to begin.[33]

Sculptor and stone choice

It was announced in January 2007 that Lei Yixin, an artist from the People's Republic of China, would sculpt the centerpiece of the memorial, including the statue of King[70] and the "Stone of Hope". The commission was criticized by human rights activist Harry Wu on the grounds that Lei had sculpted Mao Zedong. It also stirred accusations that it was based on financial considerations, because the Chinese government would make a $25 million donation to help meet the projected shortfall in donations. The president of the memorial's foundation, Harry E. Johnson, who first met Lei in a sculpting workshop in Saint Paul, Minnesota, stated that the final selection was done by a mostly African American design team and was based solely on artistic ability.[71]

Gilbert Young, an African American artist known for a work of art entitled He Ain't Heavy, led a protest against the decision to hire Lei by launching the website King Is Ours, which demanded that an African American artist be used for the monument.[72] Human-rights activist and arts advocate Ann Lau and American stone-carver Clint Button joined Young and national talk-show host Joe Madison in advancing the protest when the use of Chinese granite was discovered.[73] Lau decried the human rights record of the Chinese government and asserted that the granite would be mined by workers forced to toil in unsafe and unfair conditions.[74] Button argued that the $10 million in federal money that has been authorized for the King project required it to be subject to an open bidding process.[75]

The memorial's design team visited China in October 2006 to inspect potential granite to be used.[76] The project's foundation has argued that the quality of the Chinese granite exceeds that which can be found in the United States.[77]

Young's King Is Ours petition demanded that an African American artist and American granite be used for the national monument, arguing the importance of such selections as a part of the memorial's legacy. The petition received support from American granite workers[78][79] and from the California State Conference of the NAACP.[80][81]

In May 2008, the CFA, one of the agencies which had to approve all elements of the memorial, raised concerns about "the colossal scale and Social Realist style of the proposed sculpture," noting that it "recalls a genre of political sculpture that has recently been pulled down in other countries."[77] The commission did, however, approve the final design in September 2008.[68]

In September 2010, the foundation gave written promises that it would use local stonemasons to assemble the memorial. However, when construction began in October, it appeared that only Chinese laborers would be used. The Washington area local of the Bricklayers and Allied Craftsworkers union investigated and determined that the workers were not being paid on a regular basis, with all of their pay being withheld until they return to China.[82]

Quotation paraphrase

As noted above, one of the two quotes on the sides of the Stone of Hope—"I was a drum major for justice, peace, and righteousness"—has turned out to be a misquote.[49] Maya Angelou was one of the first critics to point out that the quote is a paraphrase of a much longer quotation, which is crucial to understanding what King was saying.[49] The full quote, taken from a February 4, 1968, sermon King delivered at the Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, on the subject of what kind of eulogy might be given at his death, was: “If you want to say that I was a drum major, say that I was a drum major for justice. Say that I was a drum major for peace. I was a drum major for righteousness. And all of the other shallow things will not matter.”[49] According to a spokesperson for the Memorial, the quote was shortened because the longer quote would not have fit the space allotted to it, but Angelou says that the present quote makes King sound arrogant—and "he had no arrogance at all," and therefore a change should be made.[49]

On September 2, 2011, The Washington Post published an editorial entitled "A Monumental Misquote," stating that if one reads the "5,000 word sermon from which the quote was taken," the paraphrase now inscribed on the Stone of Hope "is almost the opposite of what the civil rights leader intended."[54] The original sermon was about the evil King labeled as "the Drum-Major Instinct," the "evils of self-promotion."[54] The editorial continues:

"Dr. King argues that the instinct can be harnessed for noble ends, but only by doing good works and not by seeking accolades for doing them. Notably, he sought no such accolade himself. "If you want to say I was a drum major," he said, "say that I was a drum major for justice." Remove the "if"—as the architects of the monument did—and you are perversely left with the sort of bragging that Dr. King decried."[54]

Agreeing with Maya Angelou's position that the wording on the monument be changed, the Post's editorial ended by stating that "Generations of Americans are going to learn about this hero by what they see when they visit his monument. It is not too much to ask that what they learn is right."[54] However, as of September 3, 2011, Ed Jackson, Jr., the monument's executive architect, said that the inscription will not be changed.[83]

Artworks commemorating African-Americans in Washington, D.C.

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial takes its place as the "most prominent" of a number of memorials, statues, and works of art in honor of African Americans in the nation's capital.[21] As one Washington Post article stated—in a special August 24, 2011 section dedicated to the opening of the King Memorial—"In a city crowded with memorials and monuments, a few represent the individual struggles of African American pioneers or salute the contributions of black citizens."[21] Noting that African Americans are included in memorials to all Americans, such as the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, the Vietnam Women's Memorial, the Korean War Veterans Memorial, and the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial, the article listed thirteen special "artworks" commemorating African Americans as individuals and a people.[21] Among them are the Emancipation Memorial, featuring Abraham Lincoln and a newly-freed slave; Lady Fortitude, "an abstract form more than 12 feet tall...[that] represents the strength of African American women"; a life-sized statue of Mary McLeod Bethune; "Negro Mother and Child," a 1934 piece in the basement courtyard of the Interior Department; a bust of Sojourner Truth, the only African American woman in the Capitol Visitor Center; a wooden statue of St. Martin de Porres; the terra cotta frieze, "The Progress of the Negro Race," following "the journey of African Americans from slavery to the migration North around World War I; "The Shaw Memorial," a sculpture "considered one of the best sculptures of the 19th century," located in the National Gallery of Art"; a bust of Philip Randolph in Union Station; (Here I Stand) In the Spirit of Paul Robeson]], "an abstract tribute to the singer, actor, and activist"; the bust of Dr. King in the United States Capitol Rotunda; and the "Spirit of Freedom: African American Civil War Memorial," at 10th and U Streets, Northwest.[21]

References

- ^ "The National Mall". National Mall Plan. Vol. Foundation statement for the National Mall and Pennsylvania Avenue National Historic Park. National Park Service. pp. 6–10. Retrieved September 1, 2011.

- ^ a b Adam Fetcher, David Barna, Carol Johnson (August 29, 2011). "Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Becomes 395th National Park". nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved September 1, 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c "Site Location - Build the Dream". Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial Project Foundation, Inc. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ "A Dream Fulfilled, Martin Luther King Memorial Opens". New York Times. August 22, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Cooper, Rachel. "Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial in Washington, DC: Building a Memorial Honoring Martin Luther King, Jr". About.com, a part of The New York Times Company. Retrieved August 24, 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ a b "Lincoln Memorial". We Shall Overcome: Historic Places of the Civil Rights Movement: A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary. National Park Service. Retrieved September 14, 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ Associated Press. "Dedication of MLK Memorial postponed by hurricane". USA Today. Retrieved August 25, 2011.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b Weil, Martin (September 11, 2011). "MLK memorial dedication set for Oct. 16". Post Local. The Washington Post. Retrieved September 12, 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ a b Associated Press (September 14, 2011). "New date set for MLK memorial dedication". CBSNEWS. Retrieved September 14, 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ Schlesinger, Arthur M. (2002) [1965], A Thousand Days: John F. Kennedy in the White House, p. xiv

- ^ D'Souza, Placido P. (January 20, 2003). "Commemorating Martin Luther King Jr.: Gandhi's influence on King". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Krugman, Paul R. (2007), The Conscience of a Liberal, p. 85

- ^ Lischer, Richard. (2001). The Preacher King, p. 3.

- ^ a b c "Martin Luther King - Biography". Nobel Media AB. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ Michael E. Eidenmuller. "Martin Luther King, Jr: A Time to Break Silence (Declaration Against the Vietnam War)". American Rhetoric. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ Sullivan, Bartholomew. "Martin Luther King Jr. focused on ending poverty". The Commercial Appeal. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ "1968: Martin Luther King shot dead". On this Day. BBC. 1968-04-04. Retrieved 2008-08-27.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|year=/|date=mismatch (help) - ^ "Martin Luther King Day in United States". Time and Date AS. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ "Office of the Clerk of the U.S. House of Representatives Art & History - Gold Medal". Office of the Clerk of the United States House of Representatives. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ "Presidential Medal of Freedom". NNDB. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Trescott, Jacqueline, "African Americans honored by artworks throughout D.C.," The Washington Post, August 24, 2011, page H17.

- ^ Wax, Emily, "In many cultures, his message resonates," The Washington Post, August 24, 2011, page H14.

- ^ "Mission & Vision - Build the Dream". Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial Project Foundation, Inc. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ "The President's Letter - Build the Dream". Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial Project Foundation, Inc. August 28, 2011. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ "Martin Luther King, Jr". Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Eta Lambda chapter. Retrieved December 31, 2008. [dead link]

- ^ "1950-59 |". 17th-house.com. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ a b Wesley, Charles H. (1981). The History of Alpha Phi Alpha, A Development in College Life (14th ed.). Chicago, IL: Foundation. pp. 381–386. ASIN: B000ESQ14W.

- ^ Gray, Butler T. (2006). "National Mall Site Chosen for Memorial to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr". black-collegian.com. Retrieved December 12, 2008.

- ^ Wheeler, Linda (December 5, 2000). "'Sacred Ground' Dedicated to King; Plaque Placed at Site of Memorial for Civil Rights Leader". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ a b "King Memorial Raises Goal by $20 million". Alpha Phi Alpha. Associated Press. August 13, 2008. Retrieved April 16, 2009.

- ^ Malone, Julie (December 4, 2008). "Rights pioneers visit King site]". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- ^ "NAR Donates $1 million to the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial". National Association of Realtors. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- ^ a b c Zongker, Brett. (2009, October 29). "Construction to begin on King memorial in DC", Associated Press[dead link]

- ^ Ruane, Michael E. (February 11, 2011). "Massive King memorial nearly ready for trip to Mall for assembly". The Washington Post. Washington, D.C.: The Washington Post Company. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- ^ Quinn, Christopher (January 17, 2010). "King Memorial done by 2011, construction started". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ Ruane, Michael (December 2, 2010). "Stone by Stone, 'Hope' rises". Washington Post. p. B1.

- ^ "Site Location - Build the Dream". Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial Project Foundation, Inc. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ a b "Tears Fall At The Martin Luther King, Jr., Memorial". WUSA. June 30, 2011. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ a b "Design Elements - Build the Dream". Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial Project Foundation, Inc. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ a b "Composition and Space - Build the Dream". Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial Project Foundation, Inc. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ Weekend Edition Saturday (January 15, 2011). "King's Memorial To Stand Among D.C.'s Honored". NPR. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Martin Luther King Jr. National Memorial Review". Fodor's Travel Guides. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ a b Johnston, Lori (February 8, 2010). "Q: How is it that Martin Luther King Jr. gets a memorial on the mall in Washington, D.C.? I was under the impression that only presidents were entitled to have a memorial". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ "John Ericsson National Memorial (U.S. National Park Service)". National Park Service. February 14, 2011. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ "JONES, John Paul: Memorial north of - across Independence Ave - near the Tidal Basin in Washington, D.C. by Charles Henry Niehaus located in James M. Goode's The Mall area". dcmemorials.com. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ a b Golub, Evan. "Quotations from Inscription Wall of Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial". Demotix. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ "Martin Luther King Memorial Wall". About.com. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ "Council of Historians SelectsMartin Luther King, Jr. Quotations to Be Engraved Into Memorial - Build the Dream". Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial Project Foundation, Inc. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Weingarten, Gene, and Ruane, Michael, "Maya Angelo Says King Memorial Inscription Makes Him Look Arrogant, The Washington Post, August 31, 2011, retrieved August 31, 2011.

- ^ "Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial, official brochure prepared by the National Mall and Memorial Parks, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, D.C.

- ^ a b c "Design Elements - Build the Dream". Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial Project Foundation, Inc. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ "Announcement of Quotations to Be Engraved on Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial - 'Stone of Hope' Sculptor to Be Named - Build the Dream". Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial Project Foundation, Inc. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ "Obama, MLK Memorial Wrong on 'Arc' Quote". Newsmax. August 26, 2011. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e "A monumental misquote on the Martin Luther King Jr. memorial". The Washington Post. August 29, 2011. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ "National Mall Times," National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Vol. 4, Issue 8, August 2011.

- ^ "Week of Dedication". Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial Project Foundation, Inc. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ "MLK Jr. Memorial Dedication Postponed Indefinitely". NBC News. August 25, 2011. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- ^ "Dedication of King memorial postponed due to Irene". CNN. August 25, 2011. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- ^ Nuckols, Ben (August 25, 2011). "Dedication of MLK Memorial Postponed by Hurricane". ABCNews. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- ^ a b c d "Obama to speak at King memorial dedication in D.C." The Washington Post. August 16, 2011. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ Boorstein, Michelle (August 25, 2011). "Earthquake-damaged Washington National Cathedral needs to raise millions". Post Local. Washington Post. Retrieved August 25, 2011.

{{cite web}}: External link in|work= - ^ "MLK memorial taking shape on Washington's Tidal Basin". ABC Action News. January 17, 2011. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

- ^ Fears, Darryl (April 8, 2002). "Entrepreneurship of Profiteering? Critics Say King's Family Is Dishonoring His Legacy". jessejacksonjr.org. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- ^ "King Family Takes Fees From Funds Raised for the MLK Memorial Project". Fox News. Associated Press. April 17, 2009. Retrieved April 17, 2009.

- ^ Shirek, John, "King Center: MLK's Children Not Making Money on Memorial," WXIA-TV, April 22, 2009.

- ^ Jonathan Turley (April 22, 2009). "Cashing in on Martin Luther King Jr". latimes.com. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- ^ Haines (Associated Press) (August 23, 2011). "After long struggle, MLK has home on National Mall". foxnews.com. Fox News Channel. Retrieved August 26, 2011.

- ^ a b Schwartzman, Paul. (2008, December 4). "Dispute Over Security Delays Construction", The Washington Post

- ^ a b Ruane, Michael E. (2009, October 27). "Start of MLK memorial's construction all but secured", The Washington Post

- ^ "Chinese master sculptor to produce MLK memorial carving". CNN. February 15, 2007.

- ^ Cha, Ariana Eunjung (August 14, 2007). "A King Statue 'Made in China'?". Arts & Living.

- ^ Young, Gilbert. "King is Ours". The He Ain't Heavy Foundation. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lau, Ann (September 18, 2007). "Dissing MLK". National Review. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- ^ 2007-08-24 International Herald Tribune, "Martin Luther King, Jr. monument planners criticized for selecting Chinese sculptor for job"

- ^ 2007-11-15, The Randolph Herald, "Button: Event raised profile of MLK project"

- ^ "History of the Memorial". Washington, DC Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial Project Foundation, Inc. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- ^ a b Shaila Dewan (May 18, 2008). "Larger Than Life, More to Fight Over". New York Times,

New York Times, Inc. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

{{cite news}}: line feed character in|publisher=at position 16 (help) - ^ 2007-11-08, Times Argus[full citation needed]

- ^ 2007-11-09, Burlington Free Press[full citation needed]

- ^ 2007-11-28, San Francisco Chronicle[full citation needed]

- ^ 2007-10-29, California State NAACP Resolution #11[full citation needed]

- ^ Shin, Annys (November 24, 2010). "MLK memorial gets union's attention". Washington Post. p. B1.

- ^ "MLK Memorial architect says inscription will stay - politics - msnbc.com". MSNBC. Retrieved September 10, 2011.

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (August 2011) |

- Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial official NPS website

- January 18, 2008 C-Span Video

- Washington, D.C. Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial website

- Memorial Current Events

- Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Virtual Tour

- Public Law 104-333 Congressional authorization for memorial to Martin Luther King, Jr.

- "Shipping problems delay King memorial on national Mall", video by The Washington Post

- List of monuments to Martin Luther King, Jr.