Head: Difference between revisions

m Changing {{attention}} to {{cleanup-date|April 2006}} |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

The adult cranium is separated into several bones, several of which are mirrored on the right and left sides of the skull. Descriptions of these bones often use terms of [[anatomical position]] to more accurately depict how the bones relate to each other: |

The adult cranium is separated into several bones, several of which are mirrored on the right and left sides of the skull. Descriptions of these bones often use terms of [[anatomical position]] to more accurately depict how the bones relate to each other: |

||

[[Image:Skull-Schaedel.jpg|thumb|Heikenwaelder Hugo : Skull]] |

|||

* two [[maxilla]]e (one on each side of the head) that cover the inferior and medial to the [[orbit|eye socket]] (or orbit) |

* two [[maxilla]]e (one on each side of the head) that cover the inferior and medial to the [[orbit|eye socket]] (or orbit) |

||

* two [[zygomatic bone]]s, inferior and lateral to the orbit |

* two [[zygomatic bone]]s, inferior and lateral to the orbit |

||

Revision as of 16:08, 27 April 2006

- For other uses of the word head, see head (disambiguation).

You must add a |reason= parameter to this Cleanup template – replace it with {{Cleanup|April 2006|reason=<Fill reason here>}}, or remove the Cleanup template.

In anatomy, the head of an animal is the anterior part (from anatomical position) that usually comprises the brain, eyes, ears, nose, and mouth (all of which aid in various sensory functions, such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste). Some very simple animals may not have a head, but many bilaterally symmetric forms do.

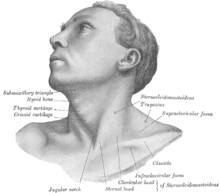

Anatomy in humans

The front (ventrum) of the head, where the eyes, ears, and mouth are located, is called the face. The area above the eyes is called the forehead (the front of the head). Below the mouth is the chin. Younger aged humans and some older humans' heads have a continuously growing layer of hair covering the head. Most females of the human race do not lose this covering during the aging process, however some males can lose their head hair as they grow older. (See Baldness)

In most complex animals the head is joined to the rest of the body by the neck.

Bones of the head

The bones of the human head are collectively called the skull. The skull is divided into the cranium (all the skull bones except the mandible) and the mandible (or jawbone). One feature that distinguishes mammals and non-mammals is that there are also three ear bones (called ossicles):

These ossicles are important components in the sense of hearing in mammals. Other animals have a single bone that is usually called the columella.

The cranium can be divided into a skull cap (or calvarium) and base. The cranium consists of several bones which fuse together at junctions called sutures. Several sutures join to form a pterion. This process of bone fusion occurs in utero to protect the most important organ in the body, the brain. Although most fusing is complete before birth, there are large areas of fibrous tissue (called fontanelles) where fusion is incomplete until puberty. The fontanelle above the forehead in newborns and young children is particularly easy to identify by touch.

The adult cranium is separated into several bones, several of which are mirrored on the right and left sides of the skull. Descriptions of these bones often use terms of anatomical position to more accurately depict how the bones relate to each other:

- two maxillae (one on each side of the head) that cover the inferior and medial to the eye socket (or orbit)

- two zygomatic bones, inferior and lateral to the orbit

- two temporal bones, covering an area where the ears are located

- a single frontal bone, superior to the orbit

- two parietal bones, posterior to the frontal bone and superior to the temporal bone

- an occipital bone at the back of the head

- several more internal bones which are not easily seen which are

- a sphenoid bone

- an ethmoid bone

- two lacrimal bones

- two nasal bones

- two palatine bones

- two nasal conchae (inferior)

- a vomer

There are a total of 14 bones in the face.

The rest of the skull is the mandible, a bone attached to the cranium at the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). This important joint allows the mandible to move, using the TMJ as a pivot to achieve actions such as chewing (mastication), eating, and speech.

When viewed from below (inferiorly) the skull contains several holes (or foramina), the largest of which is the foramen magnum through which the spinal cord passes. Other holes allow for the passage of arteries, veins, and nerves (the cranial nerves). When the skull cap (or calvarium) is removed, the base of the skull is viewed from above, there are three clear impressions or fossa. The most anterior of these is the anterior cranial fossa, where, amongst other things, upon which the frontal lobe of the brain lies. The butterfly-shaped middle cranial fossa is the second most anterior depression, the wings of which serve as a base for the brain's temporal lobes. The body of the butterfly houses an important structure, the sella turcica (Latin for Turkish saddle), which encapsulates the pituitary gland, one of the major organs of the endocrine system. The posterior cranial fossa is where the foramen magnum is located and where the posterior lobe of the brain and the cerebellum lie.

Anatomy of the face

Anatomically, the face stretches from the point of the chin to the roots of hair. The skin of the face is quite pliable and loose. Owing to the face's lack of deep fascia, facial wounds tend to bleed rather freely.

There are five orifices on the face: two for the eyes, two nostrills, and the mouth.

The blood supply to the face and indeed the most of the scalp comes mainly from the external carotid artery.

The sensory supply to the face comes solely from the trigeminal nerve (the fifth cranial nerve), so named because it branches into three divisions. The ophthalmic division covers an area above the eyes, including the forehead and most of the nose. The maxillary division covers an area below the eyes but above the mouth, including the cheeks and some of the nose. The mandibular division covers an area below the mouth and to the sides of the cheeks to the ears. This area does not cover the mandibular angle (the protrusion on the jawbone), which is innervated by the second cervical spinal nerve.

The muscles in the face include the nasal muscles, zygomatic muscles, muscles of mastication (chewing), and those of facial expression. The frontal part of the large occipitofrontalis muscle contains two parts, the occipital part (or occipitalis) and the frontal part (or frontalis). Although the two muscles are separate and supplied by different nerves, they are connected by fibromuscular tissue (called the galea aponeurotica) that stretches across the top half of the head to form the scalp. This arrangement of two different muscles attached together constitutes a digastric muscle, the actions of which are to wrinkle the forehead and raise the eyebrow. The muscle is attached to the skin of the forehead and eyebrow in front (anteriorly) and to the superior nuchal line in back (posteriorly). The frontal belly of the digastric muscle is supplied by the temporal nerve, a branch of the facial nerve (the seventh cranial nerve) while the occipital belly is supplied by another branch of the facial nerve, the posterior auricular nerve.

Anatomy in non-humans

Bilateral symmetry

The very simplest animals do not have a head, but many bilaterally symmetric forms do. In vertebrates the contents of the head are protected by an enclosure of bone called the skull, which is attached to the spine.

Cultural import

For humans, the head and particularly the face are the main distinguishing feature between different people, due to their easily discernible features such as hair and eye color, nose, eye and mouth shapes, wrinkles, etc.

People who are more intelligent than normal are sometimes depicted in cartoons as having bigger heads, as a way of indicating that they have more brains; in science fiction, an extraterrestrial having a big head is often symbolic of high intelligence. However, minor changes in brain size do not have much affect on intelligence in humans. [1]

In English slang, sometimes a boastful individual is said to have a "big head."

Clothing

Unlike other parts of the body clothing is most often not worn on the head. The most common headwear is a hat. Hats serve to keep the head warm, and to protect against precipitation or the sun. Women in islamic cultures sometimes wear veils which cover the hair and sometimes some portion of the face.

Hoods or balaclavas are designed mainly to keep the head, neck and face warm but may also hide the face. Wearing of non-religious clothing that hides the face when not climatically necessary is often considered offensive, because it affords the wearer a threatening anonymity. Terrorist or violent rebel organisations are sometimes famed for wearing balaclavas or other face covering material,such as a bandana. Face-covering headgear is also sometimes worn by those who wish to hide a facial disfigurement.

Pseudoscientific study of the human head

Because the human head is the location of the thinking organ, it has been the subject of intense study. Some of the early modern research on the human head by German physician Franz Joseph Gall has resulted in the pseudoscience of phrenology, which reached its peak in the 19th century. It attributes character traits and mental abilities to the shape of the head. The measurement of the human head and skull, known as craniometry, gained popularity at the same time. Some, notably in Nazi Germany, have used these measurements and other comparative research as the underpinnings of racist, pseudoscientific theories.

The procedure of trepanation has also been advocated and practiced for pseudoscientific reasons.

References

- Mike Hunt, Human Evolution: An Introduction to Man's Adaptations (4th edition), ISBN 0202020428