Heaven's Gate (film): Difference between revisions

references |

→Representation of the Johnson County War: more references |

||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

==Representation of the Johnson County War== |

==Representation of the Johnson County War== |

||

Apart from being set in Wyoming and the fact that many of the characters have the names of key figures in the [[Johnson County War]], the plot and the characters themselves have almost no relation to the actual historical people and events. To begin with, there was [[History of Wyoming|absolutely no question of poor European immigrant hordes trying to settle in Wyoming]], let alone killing rich men's cattle out of hunger. Secondly, far from being an "enforcer" for the stockmen, and a murderer, [[Nate Champion]] was a well-liked small rancher in [[Johnson County, Wyoming|Johnson County]], whom the rich stockmen dubbed "king of the rustlers" because he stood up against their tactic of claiming all [[Maverick (animal)|unbranded young cattle]] on the range. [[Ellen_Watson#Life_with_Averell|Jim Averell]] was also a small-time rancher, about a hundred miles southwest of Johnson County. Along with his common-law wife [[Ella Watson|Ellen (or Ella) Watson]], he was murdered by rich stockmen two years before the Johnson County War. Stockmen spread a story that Ella Watson exchanged sexual favors for stolen cattle, but this was false. She was certainly not a bordello madam. It is unlikely that Watson or Averell ever knew Nate Champion. There are numerous other ways in which the film bears little or no resemblance to history, or turns history completely upside-down. |

Apart from being set in Wyoming and the fact that many of the characters have the names of key figures in the [[Johnson County War]], the plot and the characters themselves have almost no relation to the actual historical people and events. To begin with, there was [[History of Wyoming|absolutely no question of poor European immigrant hordes trying to settle in Wyoming]], let alone killing rich men's cattle out of hunger. Secondly, far from being an "enforcer" for the stockmen, and a murderer, [[Nate Champion]] was a well-liked small rancher<ref>[http://www.wyohistory.org/print/essays/johnson-county-war The Johnson County War: 1892 Invasion of Northern Wyoming</ref> in [[Johnson County, Wyoming|Johnson County]], whom the rich stockmen dubbed "king of the rustlers" because he stood up against their tactic of claiming all [[Maverick (animal)|unbranded young cattle]] on the range<ref>[http://www.wyohistory.org/print/essays/johnson-county-war The Johnson County War: 1892 Invasion of Northern Wyoming</ref>. [[Ellen_Watson#Life_with_Averell|Jim Averell]] was also a small-time rancher, about a hundred miles southwest of Johnson County. Along with his common-law wife [[Ella Watson|Ellen (or Ella) Watson]], he was murdered by rich stockmen two years before the Johnson County War. Stockmen spread a story that Ella Watson exchanged sexual favors for stolen cattle, but this was false. She was certainly not a bordello madam. It is unlikely that Watson or Averell ever knew Nate Champion. There are numerous other ways in which the film bears little or no resemblance to history, or turns history completely upside-down.<ref>[http://www.wyohistory.org/print/essays/johnson-county-war The Johnson County War: 1892 Invasion of Northern Wyoming</ref> |

||

The true history of the [[Johnson County War]] goes something like this: In April 1892, some of Wyoming’s biggest cattlemen enlisted 23 hired killers from Texas<ref>[http://www.lib.utexas.edu/taro/tamucush/00155/tamu-00155.html Inventory of the Johnson County War Collection] ''[[Texas A&M University]] |

The true history of the [[Johnson County War]] goes something like this: In April 1892, some of Wyoming’s biggest cattlemen enlisted 23 hired killers from Texas<ref>[http://www.lib.utexas.edu/taro/tamucush/00155/tamu-00155.html Inventory of the Johnson County War Collection] ''[[Texas A&M University]]"</ref>,<ref>[http://www.wyohistory.org/print/essays/johnson-county-war The Johnson County War: 1892 Invasion of Northern Wyoming</ref> and (along with a very sympathetic newspaper reporter<ref>[http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=9907E6DA1438E233A25750C2A9629C94639ED7CF To Kill Seventy Rustlers]". April 23, 1892</ref>,<ref>[http://www.wyohistory.org/print/essays/johnson-county-war The Johnson County War: 1892 Invasion of Northern Wyoming</ref>) "invaded" north-central Wyoming to kill "rustlers." They had a hit list of 70 local people to be murdered<ref>[http://www.lib.utexas.edu/taro/tamucush/00155/tamu-00155.html Inventory of the Johnson County War Collection] ''[[Texas A&M University]]"</ref>, including the sheriff and many other prominent citizens of [[Buffalo, Wyoming|Buffalo]]. The big stockmen were upset because as more small-time ranches were established in the region, they were no longer able to use this land for their own gigantic herds of cattle. Immediately after the invaders killed Nate Champion and his friend Nick Ray, the citizens of Buffalo were alerted to the situation by a neighbor who had witnessed this event as he rode past. The citizens quickly mobilized and eventually turned the tables, surrounding the intruders at a local ranch, where they intended to capture them by force. An appeal for help by Wyoming's [[Amos Barber|Acting Governor]] (who was in close cahoots with the cattlemen<ref>[http://www.wyohistory.org/print/essays/johnson-county-war The Johnson County War: 1892 Invasion of Northern Wyoming</ref>) convinced President [[Benjamin Harrison]] to call out the army from nearby [[Fort McKinney (Wyoming)|Fort McKinney]], and after an all-night ride the soldiers arrived just in time to save the invaders. Though taken prisoner and taken to [[Cheyenne, Wyoming|Cheyenne]], they later avoided prosecution through the manipulation of public opinion by shrewd [[Fox News Channel|partisan journalism]], and through cunning legal manoeuvres.<ref>[http://www.wyohistory.org/print/essays/johnson-county-war The Johnson County War: 1892 Invasion of Northern Wyoming</ref> |

||

==Cast== |

==Cast== |

||

Revision as of 05:44, 28 September 2012

| Heaven's Gate | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Michael Cimino |

| Written by | Michael Cimino |

| Produced by | Joann Carelli |

| Starring | Kris Kristofferson Christopher Walken Isabelle Huppert Jeff Bridges John Hurt |

| Cinematography | Vilmos Zsigmond |

| Edited by | Lisa Fruchtman Gerald Greenberg William Reynolds Tom Rolf |

| Music by | David Mansfield |

Production company | Partisan Productions |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 216 minutes (director's cut restored in 2012) |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | US$44 million[2] |

| Box office | $3,484,331[3] |

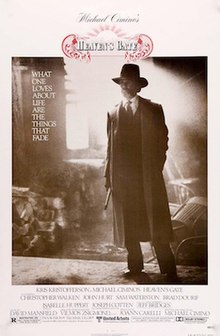

Heaven's Gate is a 1980 American epic Western film portraying a fictional dispute between land barons and European immigrants in Wyoming in the 1890s. The film very loosely and inaccurately represents some events of the Johnson County War. The cast includes Kris Kristofferson, Christopher Walken, Isabelle Huppert, Jeff Bridges, John Hurt, Sam Waterston, Brad Dourif, Joseph Cotten, Geoffrey Lewis, Richard Masur, Terry O'Quinn, Mickey Rourke, and Willem Dafoe, in his first film role.

There were major setbacks in the film's production due to cost and time overruns, negative press, and rumors about director Michael Cimino's allegedly overbearing directorial style. It is generally considered one of the biggest box office bombs of all time, and in some circles is considered to be one of the worst films ever made. It opened to poor reviews and earned less than $3 million domestically (from an estimated budget of $44 million), eventually contributing to the collapse of its studio, United Artists, and effectively destroying the reputation of Cimino, previously one of the ascendant directors of Hollywood owing to his celebrated 1978 film The Deer Hunter, which had won Academy Awards for Best Picture and Best Director in 1979.[4]

Cimino had an expansive and ambitious vision for the film and pushed the film far over its planned budget. The film's financial problems and United Artists' subsequent demise led to a move away from director-driven film production in the American film industry and a shift toward greater studio control of films.[5]

Plot summary

In 1870, two young men, Jim Averill (Kris Kristofferson) and Billy Irvine (John Hurt), are graduating from Harvard College. The Reverend Doctor (Joseph Cotten) speaks to the graduates on the association of "the cultivated mind with the uncultivated," and the importance of "the education of a nation." Irvine, brilliant but obviously intoxicated, follows this with his opposing, irreverent views. A celebration is then held after which the male students serenade the women present, including Averill's girlfriend.

Twenty years later, Averill is passing through the booming town of Casper, Wyoming on his way north to Johnson County where he is now a Marshal. Poor European immigrants new to the region are in conflict with wealthy, established cattle barons organized as the Wyoming Stock Growers Association; the newcomers sometimes steal their cattle for food. Nate Champion (Christopher Walken) – a friend of Averill and an enforcer for the stockmen – kills a settler for suspected rustling and dissuades another from stealing a cow. At a formal board meeting, the head of the Association, Frank Canton (Sam Waterston), tells members, including a drunk Irvine, of plans to kill 125 named settlers, or "thieves and anarchists" as Canton calls them. Irvine leaves the meeting and encounters Averill, telling him of the Association's "death list". As Averill leaves, he exchanges bitter words with Canton and punches him. That night, Canton begins recruiting men to kill the named settlers.

Ella Watson (Isabelle Huppert), a Johnson County bordello madam who accepts stolen cattle as payment for use of her prostitutes, is infatuated with both Averill and Champion. Averill and Watson skate in a crowd, then dance alone, in an enormous roller skating rink called "Heaven's Gate", which has been built by local entrepreneur John L. Bridges (Jeff Bridges). Averill gets a copy of the Association's death list from a baseball-playing U.S. Army captain and later reads the names aloud to the settlers, who are thrown into terrified turmoil. Cully (Richard Masur), a station master and friend of Averill's, sees the train with Canton's posse heading north and rides off to warn the settlers, but is murdered en route. Later, a group of men come to Watson's bordello and rape her. All but one are shot and killed by Averill. Champion, realizing that his landowner bosses seek to eliminate Watson, goes to Canton's camp and shoots the remaining rapist, then refuses to participate in the slaughter.

Canton and his men encounter one of Champion's friends (Geoffrey Lewis) leaving a cabin with Champion and his friend Nick (Mickey Rourke) inside, and a gun battle ensues. Attempting to save Champion, Watson arrives in her wagon and shoots one of the hired guns before escaping on horseback. Champion and his two friends are killed in a massive, merciless barrage which ends with his cabin in flames. Watson warns the settlers of Canton's approach at another huge, chaotic gathering at "Heaven's Gate". The agitated settlers decide to fight back, with Bridges leading the attack on Canton's gang. With the hired invaders now surrounded, both sides suffer casualties (including a drunken, poetic Irvine) as Canton leaves to bring help. Watson and Averill return to Champion's charred and smoking cabin and discover his body along with a hand written letter documenting his last minutes alive.

The next day, Averill reluctantly joins the settlers, with their cobbled-together siege machines and explosive charges, in an attack against Canton's men and their makeshift fortifications. Again there are heavy casualties on both sides, before the U.S. Army, with Canton in the lead, arrives to stop the fighting and save the remaining besieged mercenaries. Later, at Watson's cabin, Bridges, Watson and Averill prepare to leave for good. But they are ambushed by Canton and two others who shoot and kill Bridges and Watson. After killing Canton and his men, a grief-stricken Averill holds Watson's body in his arms.

In 1903 — about a decade later — a well-dressed, beardless, but older-looking Averill walks the deck of his yacht off Newport, Rhode Island. He goes below, where an attractive middle-aged woman is sleeping in a luxurious boudoir. Averill watches her, saying nothing. The woman, Averill's old Harvard girlfriend (perhaps now his wife), awakens and asks him for a cigarette. Silently he complies, lights it, and returns to the deck.

Representation of the Johnson County War

Apart from being set in Wyoming and the fact that many of the characters have the names of key figures in the Johnson County War, the plot and the characters themselves have almost no relation to the actual historical people and events. To begin with, there was absolutely no question of poor European immigrant hordes trying to settle in Wyoming, let alone killing rich men's cattle out of hunger. Secondly, far from being an "enforcer" for the stockmen, and a murderer, Nate Champion was a well-liked small rancher[6] in Johnson County, whom the rich stockmen dubbed "king of the rustlers" because he stood up against their tactic of claiming all unbranded young cattle on the range[7]. Jim Averell was also a small-time rancher, about a hundred miles southwest of Johnson County. Along with his common-law wife Ellen (or Ella) Watson, he was murdered by rich stockmen two years before the Johnson County War. Stockmen spread a story that Ella Watson exchanged sexual favors for stolen cattle, but this was false. She was certainly not a bordello madam. It is unlikely that Watson or Averell ever knew Nate Champion. There are numerous other ways in which the film bears little or no resemblance to history, or turns history completely upside-down.[8]

The true history of the Johnson County War goes something like this: In April 1892, some of Wyoming’s biggest cattlemen enlisted 23 hired killers from Texas[9],[10] and (along with a very sympathetic newspaper reporter[11],[12]) "invaded" north-central Wyoming to kill "rustlers." They had a hit list of 70 local people to be murdered[13], including the sheriff and many other prominent citizens of Buffalo. The big stockmen were upset because as more small-time ranches were established in the region, they were no longer able to use this land for their own gigantic herds of cattle. Immediately after the invaders killed Nate Champion and his friend Nick Ray, the citizens of Buffalo were alerted to the situation by a neighbor who had witnessed this event as he rode past. The citizens quickly mobilized and eventually turned the tables, surrounding the intruders at a local ranch, where they intended to capture them by force. An appeal for help by Wyoming's Acting Governor (who was in close cahoots with the cattlemen[14]) convinced President Benjamin Harrison to call out the army from nearby Fort McKinney, and after an all-night ride the soldiers arrived just in time to save the invaders. Though taken prisoner and taken to Cheyenne, they later avoided prosecution through the manipulation of public opinion by shrewd partisan journalism, and through cunning legal manoeuvres.[15]

Cast

- Kris Kristofferson as James Averill

- Christopher Walken as Nathan D. Champion

- Isabelle Huppert as Ella Watson

- Jeff Bridges as John L. Bridges

- John Hurt as William C. "Billy" Irvine

- Sam Waterston as Frank Canton

- Brad Dourif as Mr. Eggleston

- Joseph Cotten as The Reverend Doctor

- Paul Koslo as Mayor Charlie Lezak

- Geoffrey Lewis as Trapper Fred

- Richard Masur as Cully

- Ronnie Hawkins as Major Wolcott

- Terry O'Quinn as Captain Minardi

- Mickey Rourke as Nick Ray

- Tom Noonan as Jake

- Roseanne Vela as Beautiful girl

- Willem Dafoe (uncredited)[16]

Production

In 1971, Michael Cimino submitted the original script for Heaven's Gate, then called The Johnson County War, to United Artists executives; the project was shelved when it failed to attract big name talent. In 1979, on the eve of winning two Academy Awards (Best Director and Best Picture) for The Deer Hunter, Cimino convinced UA to resurrect the project with Kris Kristofferson, Isabelle Huppert, and Christopher Walken as the leads. The film began shooting on April 16, 1979, in Glacier National Park, east of Kalispell, Montana, with the majority of the town scenes filmed in the Two Medicine area, north of the village of East Glacier Park. The film had a projected December 14 release date, and a budget of $11.6 million.

The project promptly fell behind schedule. According to legend, by day six of filming it was already five days behind schedule. As an example of his fanatical attention to detail, a street built to Cimino's precise specifications had to be torn down and rebuilt because it reportedly "didn't look right." The street in question needed to be six feet wider; the set construction boss said it would be cheaper to tear down one side and move it back six feet, but Cimino insisted that both sides be dismantled and moved back three feet, then reassembled. An entire tree was cut down, moved in pieces, and relocated to the courtyard where the Harvard 1870 graduation scene was shot. Cimino shot more than 1.3 million feet (nearly 220 hours) of footage, costing approximately $200,000 per day. (Cimino had expressed his wish to surpass Francis Ford Coppola's mark of shooting one million feet of footage for Apocalypse Now.) Despite going over budget, Cimino was not financially penalized because he had a contract with United Artists to the effect that all money spent "to complete and deliver the picture in time for a Christmas 1979 release shall not be treated as overbudget expenditures." In the book "The Hollywood Hall of Shame," it is alleged that drug use on the set may have contributed to the excessive demands of the shoot. According to an unnamed production insider, "People wonder how a movie like Heaven's Gate could cost forty million dollars. I'll tell you. Twenty million for the actual film, and another twenty million, you can bet, for all that cocaine for the cast and crew." Cimino's obsessive behavior soon earned him the nickname "The Ayatollah." The film finished shooting in March 1980, having cost nearly $30 million. Production fell behind schedule as rumors spread of Cimino demanding up to 50 takes of individual scenes and delaying filming until a cloud that he liked rolled into the frame.[17] As a result of the numerous delays, several of the musicians that were originally brought to Montana for three weeks ended up stranded there for six months; the experience, as the Associated Press put it, "was both stunningly boring and a raucous good time, full of jam sessions, strange adventures and curiously little actual shooting." The jam sessions served as the beginning of numerous musical collaborations between Bridges and Kristofferson; they would later reunite for the 2009 film Crazy Heart and for Bridges's eponymous album in 2011.[18]

As production staggered forward, United Artists seriously considered firing Cimino and replacing him with another director. It is heavily implied in the book Final Cut that Norman Jewison was asked if he would take over, but he rejected the job.

During post-production, Cimino changed the lock to the studio's editing room, prohibiting studio executives from seeing the film until he completed the editing. Working with Oscar-winning editor William Reynolds, Cimino slaved over his project. Reynolds complained how much of his work would later be undone by the director, convinced that his Western epic would be a masterpiece. According to an anonymous studio insider, "The level of pretension in that editing room was only matched by the level of disaster later on." On June 26, 1980, Cimino previewed a work print for executives at United Artists that reportedly ran five hours and twenty-five minutes, which Cimino said was about 15 minutes longer than would the final cut.[19]

United Artists refused to release the film at that length and contemplated firing Cimino.[19] Cimino re-cut the film during the summer of 1980, finally editing it down to its original premiere length of 3 hours and 39 minutes (219 minutes), the cut that would run for one week at New York's Cinema 1 theater.

Reception and critical appraisal

Initial reactions

The November 19, 1980 premiere was, by all accounts, a disaster. During the intermission, the audience was so subdued that Cimino is said to have asked why no one was drinking the champagne. He was reportedly told by his publicist, "Because they hate the movie, Michael," according to the book Final Cut, authored by United Artists executive Steven Bach.[19]

New York Times critic Vincent Canby famously panned the film, calling Heaven's Gate "an unqualified disaster," comparing it to "a forced four-hour walking tour of one's own living room."[20] Canby went even further by stating that "[i]t fails so completely that you might suspect Mr. Cimino sold his soul to obtain the success of The Deer Hunter and the Devil has just come around to collect."[20]

After a one-week run at a single New York cinema, Cimino and United Artists quickly pulled the film from release.[21] Heaven's Gate resurfaced in April 1981 in Los Angeles in a 149-minute version that Cimino had recut.[21] Reviewing the shorter cut in the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert criticized the film's formal choices and its narrative inconsistencies and incredulities, concluding that Heaven's Gate was "[t]he most scandalous cinematic waste I have ever seen, and remember, I've seen Paint Your Wagon."[22] The Los Angeles Times's Kevin Thomas issued a dissenting opinion when he reviewed the shortened film, becoming one of its few American champions and calling it "a true screen epic."[21]

Heaven's Gate closed in theaters having grossed only $1.3 million on its $44 million budget.[21]

Reassessments

In subsequent years, however, some critics have come to the defense of the film. Several critics beginning with European critics who praised the film after it played at the Cannes Film Festival.[21][23] Robin Wood was an early champion of Heaven's Gate and its reassessment, calling it "one of the few authentically innovative Hollywood films . . . . It seems to me, in its original version, among the supreme achievements of the Hollywood cinema."[24][25] David Thomson calls the film "a wounded monster" and argues that the film takes part in "a rich American tradition (Melville, James, Ives, Pollock, Parker) that seeks a mighty dispersal of what has gone before. In America, there are great innovations in art that suddenly create fields of apparent emptiness. They may seem like omissions or mistakes at first. Yet in time we come to see them as meant for our exploration."[26] Martin Scorsese has said that the film has many overlooked virtues.[27] Some of these critics have attempted to impugn the motives of the earliest reviewers. Robin Wood noted, in his initial review of the film, reviewers tended to pile on the film, attempting to "outdo [one an]other with sarcasm and contempt."[24] Several members of the cast and crew have complained that the initial reviews of the film were tainted by its production history and that daily critics were reviewing it as a business story as much as a motion picture.[21] In April 2011, the staff of Time Out London selected Heaven's Gate as the 12th greatest Western.[28]

Beyond this, much of the critical estimation of the film continues to be low; in 2008, film critic Joe Queenan of The Guardian named Heaven's Gate the worst film ever made.[4] It currently (2012) holds a 41% "rotten" rating on Rotten Tomatoes, although several of the 27 reviews aggregated there were published for the film's initial release.[29]

Controversy

Impact on the U.S. film industry

The film's unprecedented $44-million cost (equivalent to about $122 million as of 2012) and poor performance at the box office ($3,484,331 gross in the United States) generated more negative publicity than actual financial damage, causing Transamerica Corporation, United Artists' corporate owner, to become anxious over its own public image and withdraw from film production altogether.

Transamerica then sold United Artists to MGM, which effectively ended the existence of the studio. MGM would later revive the name "United Artists" as a subsidiary division. While the money loss due to Heaven's Gate was considerable, United Artists was still a thriving studio with a steady income provided by the James Bond, Pink Panther and Rocky franchises. Many movie insiders have argued that United Artists was already struggling at the time with the box office flops of Cruising and Foxes, both released earlier in 1980 (the former film was not even produced by UA).

The fracas had a wider effect on the American film industry. During the 1970s, relatively young directors such as Francis Ford Coppola, Peter Bogdanovich, and William Friedkin were given unprecedentedly large budgets with very little studio control (see New Hollywood). The studios' evolved away from the director-driven film and eventually led to the new paradigm of the high concept feature, epitomized by Jaws and Star Wars. The directors' power lessened considerably as seen in the less successful films as Friedkin's Sorcerer (1977), and Cruising (1980), and culminating in Coppola's One from the Heart and Cimino's Heaven's Gate, among other money-losers. As the new high-concept paradigm of film-making became more entrenched, studio control of budgets and productions became tighter, ending the free-wheeling excesses that begat Heaven's Gate.

The very poor box office performance of the film had an impact on Western films, which had enjoyed a revival in the late 1960s. From this point on, very few Western films were released by major studios, save for a brief revival thanks to the Oscar-winning hits Dances with Wolves and Unforgiven.

Accusations of cruelty to animals

Heaven's Gate was marred by accusations of cruelty to animals during production. One assertion was that live horses were bled from the neck without giving them pain-killers so that their blood could be collected and smeared upon the actors in a scene. The American Humane Association (AHA) asserted that four horses were killed and many more injured during a battle scene. It was claimed that one of the horses was blown up by dynamite. This footage appears in the final cut of the film.

The AHA was barred from monitoring the animal action on the set. According to the AHA, the owner of an abused horse filed a lawsuit against the producers, director, Partisan Productions, and the horse wrangler. The owner cited wrongful injury and breach of contract for willfully depriving her Arabian gelding of proper care. The suit cited "the severe physical and behavioral trauma and disfigurement" of the horse. The case was settled out of court.[30]

There were accusations of actual cockfights, decapitated chickens, and a group of cows disemboweled to provide "fake intestines" for the actors.[30] The outcry prompted the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP) to contractually authorize the AHA to monitor the use of all animals in all filmed media.[30]

Heaven's Gate is listed on AHA's list of unacceptable films.[30] The AHA protested the film by distributing an international press release detailing the assertions of animal cruelty and asking people to boycott it. AHA organized picket lines outside movie theaters in Hollywood while local humane societies did the same across the USA. Though Heaven's Gate was not the first film to have animals killed during its production, it is believed that the film was largely responsible for sparking the now common use of the "No animals were harmed..." disclaimer and more rigorous supervision of animal acts by the AHA, which had been inspecting film production since the 1940s.[31]

Versions

Heaven's Gate premiered in New York on November 19, 1980. Prior to the premiere, Cimino had rushed through post-production and editing in order to meet his contractual requirements to United Artists and to qualify for the 1980 Academy Awards.[21] The version screened at the premiere ran 219 minutes. Kristofferson joked that Cimino had worked on the film so close to the premiere that the print screened was still wet from the lab.[21]

After the aborted one-week run in New York, Cimino and United Artists pulled Heaven's Gate; Cimino wrote an open letter to the studio that was printed in several trade papers blaming unrealistic deadline pressures for the film's failure.[32] United Artists reportedly also hired its own editor to try to edit Cimino's footage into a releasable film.[32] Ultimately, Cimino's 149-minute version premiered in April 1981 and was the only cut of the film screened in wide release. This cut of the film is not just shorter but differs radically in placement of scenes and selection of takes.[24]

In 1982, Z Channel aired the 219-minute premiere version of Heaven's Gate on cable television—the first time that the longer version was widely exhibited—which Z Channel dubbed the "director's cut." As critic F.X. Feeney noted, Z Channel's broadcast of Heaven's Gate first popularized the concept of a "director's cut."[33]

When MGM (which acquired the rights to United Artists's catalog after its demise) released Heaven's Gate on VHS and videodisc in the 1980s, it released Cimino's 219-minute cut with the tagline "Heaven's Gate… The Legendary Uncut Version." Subsequent releases on laserdisc and DVD have contained only the 219-minute cut. The 149-minute cut has never been released on home video in the United States.

In 2005, MGM released Heaven's Gate in selected cinemas in the United States and Europe.[34] The 219-minute cut had to be reassembled by MGM archivist John Kirk, who reported that large portions of the original negative had been discarded.[34] The restored print was screened in Paris and presented to a sold-out audience at New York's Museum of Modern Art with a live introduction by Isabelle Huppert.[35] Nevertheless, because the project was commissioned by then-MGM executive Bingham Ray, who was ousted shortly thereafter, the budget for the project was cut and a planned wider release and DVD never materialized.[34]

Notwithstanding the wide availability of the 219-minute premiere version of Heaven's Gate and its frequent labeling as "uncut" or the "director's cut," "Cimino [has] insisted that the so-called original version did not fully correspond to his intentions, [and] that he was under pressure to bring it out for the predetermined date and did not consider [the film] ready," making even the 219-minute version essentially an unfinished film.[24]

A restored, 216-minute version of the film premiered at the Venice Film Festival in 2012 as part of the Venice Classics series [36][37]. It will be released by The Criterion Collection on Blu-ray on November 20, 2012.

Accolades

- Nominated: Best Art Direction-Set Decoration (Tambi Larsen, James L. Berkey)

- In Competition: Palme d'Or (Michael Cimino)

- Won: Worst Director - Michael Cimino

- Nominated: Worst Picture

- Nominated: Worst Screenplay

- Nominated: Worst Musical Score

- Nominated: Worst Actor - Kris Kristofferson

See also

References

- ^ "Heaven's Gate - Poster #1". IMP Awards. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

- ^ Hughes, p.170

- ^ "Heaven's Gate (1980)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ^ a b Queenan, Joe (March 21, 2008). "From Hell". Guardian.co.uk (London, England). Retrieved 2009-09-03.

- ^ Biskind, Peter (1998). Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock-'n'-Roll Generation Saved Hollywood. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80996-6. pp. 401-403

- ^ [http://www.wyohistory.org/print/essays/johnson-county-war The Johnson County War: 1892 Invasion of Northern Wyoming

- ^ [http://www.wyohistory.org/print/essays/johnson-county-war The Johnson County War: 1892 Invasion of Northern Wyoming

- ^ [http://www.wyohistory.org/print/essays/johnson-county-war The Johnson County War: 1892 Invasion of Northern Wyoming

- ^ Inventory of the Johnson County War Collection Texas A&M University"

- ^ [http://www.wyohistory.org/print/essays/johnson-county-war The Johnson County War: 1892 Invasion of Northern Wyoming

- ^ To Kill Seventy Rustlers". April 23, 1892

- ^ [http://www.wyohistory.org/print/essays/johnson-county-war The Johnson County War: 1892 Invasion of Northern Wyoming

- ^ Inventory of the Johnson County War Collection Texas A&M University"

- ^ [http://www.wyohistory.org/print/essays/johnson-county-war The Johnson County War: 1892 Invasion of Northern Wyoming

- ^ [http://www.wyohistory.org/print/essays/johnson-county-war The Johnson County War: 1892 Invasion of Northern Wyoming

- ^ "Spalding Gray's Tortured Soul". The New York Times Magazine: 5 of online version. October 6, 2011. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- ^ "The 15 Biggest Box Office Bombs -> Heaven's Gate #8". CNBC. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

- ^ Talbott, Chris (August 17, 2011). Jeff Bridges chases different muse with new album. Associated Press. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ^ a b c Bach, Steven (1985, 1999). Final Cut: Art, Money, and Ego in the Making of Heaven's Gate, the Film That Sank United Artists (New edition ed.). New York, NY: Newmarket Press.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|year=(help) - ^ a b Vincent Canby (November 19, 1980). "Movie Review - Heaven's Gate - 'HEAVEN'S GATE,' A WESTERN BY CIMINO". NYTimes.com. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Michael Epstein (2004). Final Cut: The Making and Unmaking of Heaven's Gate (Television). Viewfinder Productions.

{{cite AV media}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|trans_title=(help) - ^ Ebert, Roger (1981). "Heaven's Gate". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2012-03-13.

- ^ Khan, Omar. "Heaven's Gate (1981)"

- ^ a b c d Wood, Robin (1986). Hollywood from Vietnam to Reagan. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 267, 269, 283. ISBN 0-231-12966-1.

- ^ "Top Ten Lists by Critics and Filmmakers". Combustible Celluloid. Retrieved 2010-11-25.

- ^ Thomson, David (October 14, 2008). "Have You Seen . . . ?": A Personal Introduction to 1,000 Films. New York, NY: Random House. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-307-26461-9.

- ^ LaGravenese, Richard (director); Demme, Ted (director). (2003). A Decade Under the Influence: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow. [Film]. IFC.

- ^ "The 50 greatest westerns". Time Out (London). April 2011. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- ^ "Heaven's Gate". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

- ^ a b c d "Heaven's Gate". American Humane Association. Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- ^ "Cruel Camera". The Fifth Estate. CBC Television. May 5, 1982 and January 16, 2008. Retrieved 2010-10-12.

- ^ a b Egan, Jack (December 8, 1980). "Bombs Away". New York. p. 16. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- ^ Cassavetes, Xan (director), Feeney, F.X. (critic). (2004). Z: A Magnificent Obsession. [Film]. IFC.

- ^ a b c Macnab, Geoffrey (2/23/2005). "Heaven Can Wait". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Michael Cimino - Paris Heaven's Gate Master class". ecranlarge.com. Retrieved 2010-11-18.

- ^ Drees, Rich (August 31, 2012). "Cimino Premiers 216-Minute Cut Of HEAVEN’S GATE At Venice Film Festival". FilmBuffOnline. Retrieved 2012-09-06.

- ^ Lang, Brett (July 26, 2012). "Venice Film Festival Unveils Line-Up with Films from Malick, De Palma and Demme". The Wrap. Retrieved 2012-07-27.

- ^ a b c "Heaven's Gate (1980) - Awards". IMDb. Retrieved 2010-10-15.

- ^ "NY Times: Heaven's Gate". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-12-31.

- Bibliography

- Bach, Steven (September 1, 1999). Final Cut: Art, Money, and Ego in the Making of Heaven's Gate, the Film That Sank United Artists (Updated ed.). New York, NY: Newmarket Press. ISBN 97815570437440.

- Biskind, Peter (1998). Easy Riders, Raging Bulls: How the Sex-Drugs-and-Rock-'n'-Roll Generation Saved Hollywood. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80996-6.

- Hughes, Howard (2009). Aim for the Heart. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-902-7.

External links

- Heaven's Gate at IMDb

- Heaven's Gate at AllMovie

- Heaven's Gate at Box Office Mojo

- Heaven's Gate at Rotten Tomatoes

- Review of Heaven's Gate at TVGuide.com

- Trailer for Heaven's Gate on YouTube

- The Johnson County War: 1892 Invasion of Northern Wyoming

- 1980 films

- 1980s Western films

- American films

- American epic films

- American Western films

- English-language films

- Films directed by Michael Cimino

- Animal cruelty incidents

- Epic films

- Films shot anamorphically

- Films set in the 1890s

- Films set in Wyoming

- Films shot in Idaho

- Films shot in Montana

- Films about race and ethnicity

- United Artists films

- Pinewood Studios films