Leonid Khabarov: Difference between revisions

sentenced |

RAPSI link |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

| website = [http://leonid-habarov.com/ “Free Colonel Khabarov!”–movement<br>Official website {{ru icon}}] |

| website = [http://leonid-habarov.com/ “Free Colonel Khabarov!”–movement<br>Official website {{ru icon}}] |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Leonid Khabarov''' ({{lang-rus|Леони́д Васи́льевич Хаба́ров|p=lʲɪɐˈnʲid xɐˈbarəf}}) is a Russian [[ROTC#Non-U.S. ROTC programs|ROTC]] chief, who received broad media attention after he was arrested on [[coup d'état]] charges in 2011. He was later accused of creating a master plot in order to overthrow local authorities in the [[Ural (region)|Ural region]] of Russia for the purpose of launching a nationwide rebellion. A year and a half has passed since Khabarov was detained; however, no solid evidence in support of the alleged activities has been provided, leading to a campaign spread over the [[Commonwealth of Independent States]] in support of his immediate release. The trial sessions were routinely rescheduled.<ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.nakanune.ru/articles/16725/|title= Kvachkov′s Accomplices: The Schizo Is Out, But Schizophrenia Is Still In.|author= Hurbatov, Sergey.|date= July 25, 2012|publisher= Nakanune.ru|language= Russian|accessdate=July 25, 2012}}</ref> On February 26, 2013, 13:00 [[Moscow Time|MSK]], Sverdlovsk Regional Court sentenced Khabarov to four-and-a-half years in prison, despite nation-wide protest.<ref>{{cite web|url= http://rt.com/politics/three-sentenced-in-russia-over-coup-plot-452/|title= Russian gang convicted of coup attempt|author=Lysizin, Pavel.|date= 26 February 2013|work= Russian politics|publisher= [[Russia Today]]|accessdate=26 February 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url= http://en.rian.ru/russia/20130226/179697240.html|title= Two Jailed in Russia Over Unlikely Coup Plot|author=Lisitsyn, Pavel.|date= 26 February 2013|work= Russia|publisher= [[RIA Novosti]]|accessdate=26 February 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.interfax.co.uk/russia-news/court-in-urals-sentences-plotters-of-armed-mutiny/|title= Court in Urals sentences plotters of armed mutiny|author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.-->|date= 26 February 2013|work= Russia News|publisher= [[Interfax]]|accessdate=26 February 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url= http://rapsinews.com/|title= Accomplices in attempted armed coup given 4.5 year in prison|author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |date= 26 February 2013|work= Courts & Legislation|publisher= Russian Legal Information Agency|accessdate=26 February 2013}}</ref> |

'''Leonid Khabarov''' ({{lang-rus|Леони́д Васи́льевич Хаба́ров|p=lʲɪɐˈnʲid xɐˈbarəf}}) is a Russian [[ROTC#Non-U.S. ROTC programs|ROTC]] chief, who received broad media attention after he was arrested on [[coup d'état]] charges in 2011. He was later accused of creating a master plot in order to overthrow local authorities in the [[Ural (region)|Ural region]] of Russia for the purpose of launching a nationwide rebellion. A year and a half has passed since Khabarov was detained; however, no solid evidence in support of the alleged activities has been provided, leading to a campaign spread over the [[Commonwealth of Independent States]] in support of his immediate release. The trial sessions were routinely rescheduled.<ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.nakanune.ru/articles/16725/|title= Kvachkov′s Accomplices: The Schizo Is Out, But Schizophrenia Is Still In.|author= Hurbatov, Sergey.|date= July 25, 2012|publisher= Nakanune.ru|language= Russian|accessdate=July 25, 2012}}</ref> On February 26, 2013, 13:00 [[Moscow Time|MSK]], Sverdlovsk Regional Court sentenced Khabarov to four-and-a-half years in prison, despite nation-wide protest.<ref>{{cite web|url= http://rt.com/politics/three-sentenced-in-russia-over-coup-plot-452/|title= Russian gang convicted of coup attempt|author=Lysizin, Pavel.|date= 26 February 2013|work= Russian politics|publisher= [[Russia Today]]|accessdate=26 February 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url= http://en.rian.ru/russia/20130226/179697240.html|title= Two Jailed in Russia Over Unlikely Coup Plot|author=Lisitsyn, Pavel.|date= 26 February 2013|work= Russia|publisher= [[RIA Novosti]]|accessdate=26 February 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.interfax.co.uk/russia-news/court-in-urals-sentences-plotters-of-armed-mutiny/|title= Court in Urals sentences plotters of armed mutiny|author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.-->|date= 26 February 2013|work= Russia News|publisher= [[Interfax]]|accessdate=26 February 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url= http://rapsinews.com/legislation/20130226/266533001.html|title= Accomplices in attempted armed coup given 4.5 year in prison|author=<!--Staff writer(s); no by-line.--> |date= 26 February 2013|work= Courts & Legislation|publisher= Russian Legal Information Agency|accessdate=26 February 2013}}</ref> |

||

Khabarov is a widely celebrated former Soviet military officer whose battalion was the first [[Soviet Army]] unit to cross the border with the [[Democratic Republic of Afghanistan]] on December 25, 1979,<ref>{{cite book |title=Inside the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan and the Seizure of Kabul, December 1979|last=Lyakhovskiy|first=Aleksandr.|series=[[Cold War International History Project]]|volume=51|year=2007|publisher=[[Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars]]|location=Washington, DC|page=44|chapter=Soviet Troops Enter Afghanistan: How it began|accessdate=August 22, 2012 |url=http://wilsoncenter.tv/sites/default/files/WP51_Web_Final.pdf}}</ref> which was the [[de facto]] beginning of the decade-long [[Soviet war in Afghanistan|Soviet military campaign in Afghanistan]].<ref name="Antonov">{{cite journal|last= Antonov|first= Alexander|year= 1999|title= Storm-333: A Story Behind The Storming Of The Tajbeg Palace In 1979|journal= [[Rodina (magazine)|Rodina]]|issue= 2|language= Russian|url= http://otvaga2004.narod.ru/otvaga2004/wars1/wars_76.htm|accessdate= 2012-07-19}}</ref> |

Khabarov is a widely celebrated former Soviet military officer whose battalion was the first [[Soviet Army]] unit to cross the border with the [[Democratic Republic of Afghanistan]] on December 25, 1979,<ref>{{cite book |title=Inside the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan and the Seizure of Kabul, December 1979|last=Lyakhovskiy|first=Aleksandr.|series=[[Cold War International History Project]]|volume=51|year=2007|publisher=[[Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars]]|location=Washington, DC|page=44|chapter=Soviet Troops Enter Afghanistan: How it began|accessdate=August 22, 2012 |url=http://wilsoncenter.tv/sites/default/files/WP51_Web_Final.pdf}}</ref> which was the [[de facto]] beginning of the decade-long [[Soviet war in Afghanistan|Soviet military campaign in Afghanistan]].<ref name="Antonov">{{cite journal|last= Antonov|first= Alexander|year= 1999|title= Storm-333: A Story Behind The Storming Of The Tajbeg Palace In 1979|journal= [[Rodina (magazine)|Rodina]]|issue= 2|language= Russian|url= http://otvaga2004.narod.ru/otvaga2004/wars1/wars_76.htm|accessdate= 2012-07-19}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 10:43, 27 February 2013

Leonid Khabarov | |

|---|---|

Colonel Khabarov standing atop the Salang Pass, thirty years after he was a person in charge of the place. A veteran′s trip of 2009 | |

| Native name | Леонид Васильевич Хабаров |

| Born | May 8, 1947 Shadrinsk, Kurgan Oblast, RSFSR |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1966—1991 (active duty) 1991—2010 (ROTC) |

| Rank | |

| Unit | 56th Guards Separate Air Assault Brigade |

| Commands held | 4th Air Assault Battalion |

| Battles/wars | Afghan war |

| Awards | see Military awards |

| Relations | see Family |

| Other work | see In the ROTC |

| Signature |  |

| Website | “Free Colonel Khabarov!”–movement Official website Template:Ru icon |

Leonid Khabarov (Russian: Леони́д Васи́льевич Хаба́ров, IPA: [lʲɪɐˈnʲid xɐˈbarəf]) is a Russian ROTC chief, who received broad media attention after he was arrested on coup d'état charges in 2011. He was later accused of creating a master plot in order to overthrow local authorities in the Ural region of Russia for the purpose of launching a nationwide rebellion. A year and a half has passed since Khabarov was detained; however, no solid evidence in support of the alleged activities has been provided, leading to a campaign spread over the Commonwealth of Independent States in support of his immediate release. The trial sessions were routinely rescheduled.[1] On February 26, 2013, 13:00 MSK, Sverdlovsk Regional Court sentenced Khabarov to four-and-a-half years in prison, despite nation-wide protest.[2][3][4][5]

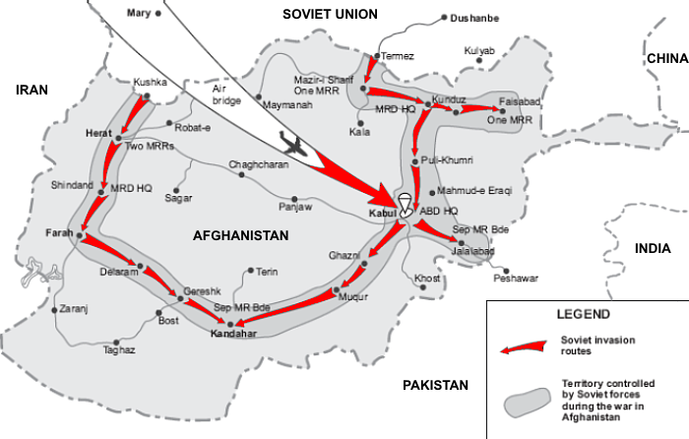

Khabarov is a widely celebrated former Soviet military officer whose battalion was the first Soviet Army unit to cross the border with the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan on December 25, 1979,[6] which was the de facto beginning of the decade-long Soviet military campaign in Afghanistan.[7]

Early years

Leonid Khabarov was born to a military family in Shadrinsk, Kurgan Oblast, on May 8, 1947. His father, Vasily Khabarov, a Red Army officer and World War II veteran, died from the battle injuries, soon after Leonid was born. His mother moved to Nizhny Tagil, where Leonid successfully finished evening school and then vocational school, having received a work qualification. He then worked for a year as an excavator operator in the Tagil industrial area.

Apart from his study and work, he has shown considerable results in amateur boxing, winning several local championships. By the time he entered the draft-age, he planned to attend a military aviation high school, but due to the nasal fracture, he acquired during his amateur career, he was rejected to enroll. Instead, he received a green light to enter Ryazan Airborne School.[a]

Though it was possible for a civil entrant, who have practical experience of operating heavy machinery, and certain sport achievements, to enroll the airborne school without having served the mandatory three-years as a conscript, he decided to serve the mandatory service first. During one of the jump sessions he received a spinal injury, but his injury did not stop him from becoming a military officer.

After three years of service within the Soviet Airborne Troops, Sgt. Khabarov, 21, has been assigned to study in the airborne school, and listed as a sophomore.

Military career

After successfully graduating from the airborne school, he has been assigned as the Commanding Officer of 100th Separate Reconnaissance Company, he brought the training process of his troops to a qualitatively new level, conducting exhausting training raids through the Taklamakan Desert, and climbing up the Pamir peaks – one of them was named “The VDV Peak,” after Khabarov and his men climbed it over.

Due to the outstanding results, shown by his recon company two years in a row (Khabarov′s men, calling themselves khabarovtsy, twice won the Soviet Airborne Troops Team Championship,) and having a perfectly unstained military record, Sr. Lt. Khabarov has been chosen by the Soviet military officials from the hundreds of other candidates, to be a main protagonist of the Skies On The Shoulders, a Soviet Armed Forces promo of half an hour length, which was aired in 1975 across the Soviet Union, gaining a significant success among the draft-age youth. For several years, he was a sort of military celebrity for the Soviet press, appearing several times on the Pravda coversheet. Army Gen. Vasily Margelov, Commander-in-Chief of the Soviet Airborne Troops, contemplating Khabarov during large-scale military exercises, noted to his retinue, that “this young fellow has great prospect.” Some time later, he insisted Khabarov to attend the Vystrel Higher Military Courses in Moscow, and after he graduated from the courses, Khabarov has been assigned as a Battalion Commander of 105th Guards Airborne Division to Chirchik.

Deployment of the troops to Afghanistan

Late at night December 24, 1979, Marshal Dmitriy Ustinov, Minister of Defence of the Soviet Union, and Marshal Nikolai Ogarkov, Chief of the General Staff, received a phone-report from Col. Gen. Yuri Maximov, Commander-in-Chief of the Turkestan Military District, who reported about troops readiness to invade the territory of Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, seizing key military and civil objects, and took over strategic locations. On December 25, at the 12:00 AM, a cipher message arrived to the troops, containing the order to cross the Afghan border, and move to the preset locations. Capt. Khabarov′s 4th Air Assault Battalion was the first Soviet Army unit to cross the border, along with 154th Separate Spetsnaz Detachment, led by Maj. Igor Stoderevsky.[7]

Khabarov and his men quickly advanced through Mazar-i-Sharif, Kunduz, and Puli Khumri, covering 279 miles deep in the Afghan territory within less than eighteen hours, with air temperature –22 °F, and seizing the Salang Pass, a strategic location on the way from USSR to Kabul.[b] The first attack on Khabarov′s garrison, successfully repelled in a matter of hours, left eighty mujahids killed, and near a hundred and fifty wounded. He remained a person in charge of the place for the following three months. Despite the harsh weather conditions, frequent blizzards, stormy wind, and mujahideen activity, there were no Soviet casualties during his chargeship.[8]

Col. Gen. Yuri Tukharinov, then Commander of the Soviet Forces in Afghanistan, later reminisced that despite Khabarov was authorized for such a crucially important role, and nearly all Soviet troops, which came by land, crossed the Salang Pass, and every Soviet soldier at least once heard his name, Tukharinov himself never seen him in person, he only heard his voice in the radio transmitters quite frequently. In his imagination, as he later owned up, Khabarov appeared to be a hero from ancient sagas, sort of a mythical King in the mountain. So was his amazement, when he finally met Capt. Khabarov, a slender redheaded man in his thirties, with a visual appearance of everyman.[9]

The Panjshir offensive of April 1980

After a few months, spent defending the Salang, Khabarov and his men dispatched to Kunduz Province, engaging in several military operations. After that, the battalion and its commander were called back to Kabul, under the direct command of Commander of the Soviet Forces in Afghanistan, the abovementioned Col. Gen. Yuri Tukharinov. The Afghan resistance intensified its activities by blewing up bridges, spranging ambushes in deep ravines, and setting up heavy machine-guns in caves.[10]

By the late March 1980, Khabarov received an order, to prepare his troops for a major offensive in Panjshir Province, the mujahideen stronghold. Located between Jabal-ul-Siraj and Charikar, Khabarov′s battalion was ordered to move through the Panjshir Valley to the very end of it and back, in order to confront the resistance troops and their leader Ahmad Shah Massoud. Meanwhile, Massoud ordered his mujahideen to mine the only road in the valley.[11]

While proceeding over the mission, Khabarov′s troops covered the distance from Kabul to Shahimardan, Fergana Province, Uzbekistan, defeating several rebel groups, and seizing documentation of the Afghan National Islamic Committee, with portfolio on all rebel leaders and detailed master files. On the April 13, 1980, Khabarov and his battalion, in cooperation with units of the Afghan National Army, confronted major forces of the mujahideen. Fierce fight ensued.[8]

Injuries and treatment

Facing the mujahideen fighters at the close range, Khabarov downed several of them, and himself received few Type 56 scratch wounds, which make him bled, but were not lethal. He also received a 7.62 headshot, but again, his helmet absorbed the projectile′s energy, leaving him almost unhurt. However, he wasn′t that lucky, receiving a HMG slug. A .50 caliber bullet, almost ripped off his right hand, making him unable to pull the trigger, or use the radio. Nevertheless, he continued to command his troops via the battalion′s radioman, right until a helicopter arrived to evacuate casualties and injured. Khabarov ordered badly wounded to be evacuated, expecting that there has been left no place for him aboard the heli. Despite of his insists, that he has to command his troops, eventually, he almost succumbed to a severe blood loss, and his subordinates loaded him aboard the helicopter against his will. While flying to compound, he felt unconscious aboard the copter.[8]

He was then delivered to Kabuli military hospital, where newly grads planned to cut off what was left of his hand. However, the news soon reached Khabarov′s unofficial patron Col. Gen. Yuri Maximov, who figured out that having one of his best men handicapped, would hardly make a good publicity back in the USSR, as well as it would affect general mood of the troops, to whom such a loss of renowned man like Khabarov would be a big upset. Considering all these circumstances, Maximov ordered best of the Soviet surgeons in the country to be brought together in order to save life, and extremities of his protégé. Khabarov undergone a major surgery. Surgical team, led by Dr. Nikolayenko and Dr. Korovushkin, sewed up his hand back to the shoulder joint, and fixed the minor injuries. Soon he was transferred to Tashkent, and then, to Burdenko General Military Clinical Hospital in Moscow, where he accustomed to use his brand new, sewed-up right hand.[12] While recovering from the wounds, Khabarov has been promoted to Major, and graduated from Frunze Military Academy, and has been assigned to command a mech. inf. regiment, located near the Afghan border. However, this kind of assignment wasn′t an honorary one for Khabarov, describing his experience of being an infantry commander as a stagnant “rusty time”, so he volunteered to dispatch on the another tour of duty to Afghanistan. Following his own request, he was demoted from Regiment Commander to Brigade Chief-of-staff position, and assigned back to the 56th Air Assault Brigade.[8]

Second deployment to Afghanistan

After being severely wounded, Khabarov twice returned to combat duty.[13] Having been deployed to Afghanistan for a second time, Khabarov spent eleven month with his brigade, from October 1984 until September 1985, when the supply convoy, to which Khabarov was assigned as a security officer, trapped into an ambush, staged by the mujahideen. He engaged the fight, which was unfolding on one of serpentine mountain roads near Barikot. His BTR-80 armored vehicle, received an RPG side-shot, throwing it upside down, and rolling head over heels from the mountain. Khabarov survived the attack having his collarbone, and three ribs broken, and his right hand heavily injured again. He underwent a treatment session in Kabul, and Tashkent military hospitals.[8]

Before the fall of the USSR

| Insignia | Rank | Component | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trooper | Airborne Troops | 1965 | |

| Jr. Sgt. | Airborne Troops | 1966 | |

| Sgt. | Airborne Troops | 1967 | |

| Lt. | Airborne Troops | 1972 | |

| Sr. Lt. | Airborne Troops | 1975 | |

| Capt. | Airborne Troops | 1979 | |

| Maj. | 40th Army | 1980 | |

| Lt. Col. | Turkestan Military District | 1984 | |

| Lt. Col. | 40th Army | 1986 | |

| Lt. Col. | Carpathian Military District | 1987 | |

| Col. | Airborne Troops | 1991 |

At the time, Khabarov was recovering, President Gorbachev signed the Geneva Accords, which consequently lead to the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan in 1989, a traitorous act as to Khabarov, who thought that it was a direct betrayal of the friendly Afghani government headed by the pro-Soviet President Mohammad Najibullah.[11]

After having been recovered from the injuries, Khabarov was assigned the staff officer position at the Carpathian Military District, quartered in Lviv, Ukraine. He received huge apartments in the city, along with a quite, office job. Khabarov himself described his live in Lviv as an idyl to dream of, and service, as literally “fraying pants”.

In 1991 he celebrated twenty-five years of the active duty service. It was the first time, Khabarov faced his retirement age. He could retire earlier, using the option of a medical discharge due to the severity of suffered injuries. However, he decided not to go on pension, and asked his superiors for any chance to remain in service. High-ranked airborne officer Georgy Shpak, who became the sixteenth Russian Airborne Troops Commander-in-Chief a few years later, then Volga–Urals Military District Deputy Chief, assisted Khabarov in his transfer from Carpathian Military District to Ural.

In the reserve officers training corps

After Col. Khabarov came back from Ukraine to Ural, he received an unusual assignment, a chair in military studies within the Ural State University in Yekaterinburg. The time was rough for military education, a plethora of educational facilities has been closed, due to the budget cut-offs and chaotic situation, which emerged in the light of the Collapse of the Soviet Union. Khabarov took the challenge, and started to discover for himself a completely new military realm, i.e. training of reserve officers.[14]

Since the creation of reserve officers training facilities in the late 1920s, the prejudice exists, as to the quality of education, and skills, received by the cadets. The official objective of such education was to cross-train civil specialists, engineers and medics, in order to inculcate a set of supplementary military skills to their basic degree program. In fact it turned out to be a safe harbor for draft evaders, providing them with opportunity to dodge the mandatory active duty, and receive officer′s rank as a plus. Military officers, which were appointed to led such facilities, usually were not avid to turn the guided alma mater into a boot camp, and thus, the situation remained stale for decades, arousing skepticism among the active duty officers to their colleagues from military reserve. Ural was not the exception. Established in 1937 by Sovnarkom decree, Joint Military Chair of the Ural Industrial Institute haven′t experienced any significant changes for its semicentennial history.[14]

Khabarov, using draconian measures, succeeded in turning his God-forsaken military chair into a high profile educational facility, able to compete with conventional military schools and academies. Under his guidance, within a year, the chair has been promptly expanded to Military Department, and then, after a decade of Khabarov′s deanship, it branched off into a separate mil-tech educational facility (full name: Institute for Military Technical Education and Security, or IMTES.) He wrested off T-72, T-80 and T-90 battle tanks from the Russian Ground Forces depots for the Institute′s car park. He conducted a number of military exercises for his trainees, in cooperation with the Volga–Urals Military District Command. In 1996 Khabarov′s reconnaissance sub-department has been visited by the servicemen of the U.S. Special Forces. Apart from training his cadets in scope of the conventional warfare tactics, he encouraged innovative scientific research among his subordinates, including military robotics program, launched by the institute seniors, under his direct academic guidance.[14]

The results did not wait too long to show up. In 2003, Khabarov′s outfit was considered to be the best educational facility in the entire Russian military. In 2004, he himself was regarded as the best military academic in the country. Khabarov′s tankmen were noted as the best specialists in the Russian military, thrice in 1998, 2003 and 2005. Same did his “flaks” and “picks′n′shovels” in 2006. Institute hosted a number of conferences, visited by supreme military officials and heads of different military education facilities from across the country, and beyond.[14]

Military awards and citations

|

For his distinctive service, during the Afghan war, Khabarov has been awarded Order of the Red Banner, both classes of Medal “For Distinction in Military Service”, as well as all three classes of Medal “For Impeccable Service”, and Armed Forces of the USSR Veteran′s Medal. After the fall of the Soviet Union he was awarded Order of Military Merit and several honorary titles, in recognition of his past exploits as actions, which had been done in the sake of Russia.

In the 1980, right after he was assigned to Kabul, his subordinates, without informing him, have sent a letter to Moscow, describing Khabarov actions, while he was in charge of Salang and its neighboring area, and asking to award him Hero of the Soviet Union, the supreme Soviet military and civil award. The letter has been submitted for consideration, but at the time it has been received, Politburo denied any armed confrontation in Afghanistan, insisting that there is no such thing, which could be defined as war going on down there. Thus Khabarov′s nomination was suspended indefinitely, and he never received the Gold Star. After the USSR collapsed, this story received another boost. Sazhi Umalatova, a former Soviet parliamentary tribune, was elected Head of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR. The body was illegitimate by that time, but the new Russian authorities, led by Boris Yeltsin, was too weak to contest the powerful pro-communist sentiment, and forbade the Umalatova′s shadow government, who received wide support and got a lot of sympathizers among former apparatchiks, who still remained in power. Stripped from actual political power, Umalatova, in retaliation, claimed that the Yeltsin regime was illegitimate, and continued to create the illusion of the Soviet life going on, including, distribution of the Soviet awards. Apart from the Soviet awards, the Presidium led by Umalatova, established their own medals and orders. After they found out that Khabarov was at his time nominated for Hero of the Soviet Union, they awarded him with “Veteran Internationalist Medal,” as an acknowledgement of his Afghan feats, and “80 Years of the Soviet Armed Forces” Jubilee Medal, in recognition of quarter of a century, he spent as active duty militaryman, and almost vicennial record of his service with the ROTC. Khabarov, as well as other veterans, accepted these awards, because during the years, followed the dissolution of the USSR, it was really unclear, who′s in charge of the country. Many thought that the Union will be restored in a few years. Khabarov later commented on this dualism in his letter from Lefortovo State Prison: “I served not for the political leaders. I served for the sake of the country — Soviet Union — Russia — my Motherland.”

“Massoud? Treat him like my best friend”

No chance in the world real warrior like Massoud let him be captured by the Shuravi. What would I do to him next, if I capture him? I would order the best medical treatment of his wounds, and then, when he come back to consciousness, I personally would treat him, like if he is our greatest ally.

Leonid Khabarov on his plans,

in case if he could succeed capturing

Ahmad Shah Massoud.

All the time back in the 1980s, during his deployment to Afghanistan, Khabarov and his men encountered Massoudi troops. Khabarov never found out, who was that lucky mujah, who shot him (if, of course, he survived the war.) Khabarov was eager to know, just out of curiosity, because the man might became a pretty rich fellow, with Afghan insurgency priced Khabarov′s life worth Afs 500,000, as it was reported by the military intelligence plants, before he was shot in action.[15]

Khabarov′s bigger-than-life goal then was to find and capture Ahmad Shah Massoud, known as the Panjshir Lion, the informal leader of Afghan resistance. For that, Khabarov later dispatched on his second tour of duty, but never faced him off personally.[15]

While being to hospital, Khabarov has been asked, what he may have done to his rival Ahmad Shah Massoud, if succeeded in capturing him. Khabarov replied, that no chance such a great warrior as Massoud let him be captured by the Shuravi.[c] He could be captured by only being killed, or shot and bleeding, and being in a near-death condition, without a slightest possibility to resist. Anyway, even if have him captured, Khabarov said that he would treat Massoud, like if he was not his fierce enemy, but close ally, instead.[15]

Back to Afghanistan

In the late February 2009, Col. Khabarov and two other veterans, 22nd Separate Spetsnaz Brigade Sgt. Victor Babenko, and 345th Guards Airborne Regiment Sgt. Maj. Evgeny Teterin, visited Islamic Republic of Afghanistan on the veterans′ tour across their service path. Together they visited Salang Pass, met the officer in charge of the place, he happened to be a Colonel General of the Afghan Army (while Khabarov was only a Captain in his time.) They moved all the way through the Panjshir mountains, where fierce battles of the 1980s once unfolded.[15]

By the end of their journey, they visited Bazarak village in the Panjshir Valley, the place of burial of Ahmad Shah Massoud. Never met Massoud face to face, Khabarov asked his fellow companions to leave him alone for a minute: “Would you excuse us, guys. Me and Ahmad have a private talk.”[15]

Post-retirement life

In 2010, after almost twenty years of training reserve officers, Khabarov finally retired from service. In 2004 he was elected Deputy Chairman of the local organization of Afghan veterans. In his mid sixties, Khabarov continued his public activity as a military supporter. Since a civilian functionary Anatoly Serdyukov stood at the head of the Russian Ministry of Defence, Khabarov was his staunch critic, publicly accusing him of sabotage and destruction of the Armed Forces. Khabarov used to retort on this criticism, saying that Serdyukov, during his incumbency, succeeded in destruction of Russian Army so effectively, the CIA could only dream about decades ago. He also referred to Serdyukov, not as a statesman, but a state criminal, instead.[16]

Arrest

In 2011 Khabarov was arrested by the federal operatives. The FSB announced that Khabarov planned a major upheaval on the Airborne Troops Day, August 2, 2011. Search of his apartments discovered the custom-made sabre, presented to Khabarov in the early 2000s (decade), by then Minister of Defence Sergei Ivanov, and out-of-date promedol capsule from the soldier′s medical kit, Khabarov use to keep from his Afghan times, as a memento of the events, took place in the 1980s. These artifacts were immediately submitted to the criminal case as the evidence of his intentions. Along with the aforementioned, Dangerous By His Faithfulness To Russia, a '2006 book by Vladimir Kvachkov, has been found in Khabarov′s personal library. It was also submitted to materials of the case as the “extremist literature”, despite the book itself is freely available to buy, and it was not listed in the Federal List of Extremist Materials. The opinion has been expressed quite frequently, that Serdyukov and his henchmen were behind this arrest and the ongoing trial.[16]

According to ITAR-TASS news agency, the prosecution stated that Khabarov′s group planned to launch the operation codenamed “Dawn” to overthrow the official authorities in the region.[17]

Backlash

Many prominent figures of Russian politics expressed their outrage about the Khabarov′s enjailment. Amongst them are people of diametrically opposite political views, such as the presidential candidates Leonid Ivashov and Gennady Zyuganov, as well as other political figures, such as Andrey Illarionov, Andrey Savelyev, Maxim Shevchenko, Alexey Dymovsky, Maxim Kalashnikov, Irek Murtazin, Mikhail Delyagin, Ashot Egiazaryan, Aleksandr Kharchikov, Dmitry Puchkov, et al. They said that the accusation theory does not hold water, pointing on ridiculousness of the collected “evidences.” Khabarov′s colleague, Col. Vladislav Zyomkovsky, during his interview to PublicPost, noted, that officially announced denunciation of the failed masterplan doesn′t stand up to critical examination, and if examined, the argument just falls to the ground. In his opinion, a brilliant military strategist, Khabarov really is, would never develop such a verdant plan. To confute the official version of the failed plot, Zyomkovsky, cited one paragraph from the Khabarov′s bill of indictment, which states that Khabarov and his alleged accomplices planned to switch off the entire region, and thus create panic and civil disorder. In his opinion, this passage was copypasted from an indictment bill of the criminal trials of the 1930s, when such event could really spread chaos. But not any longer in the 2000s (decade) Russia, where switch offs happening on the everyday basis, are routine and quite common occurrence.[18]

Family

Being a third-generation military man, with his father, and grandfather, both military officers,[d] Khabarov decided to continue the family tradition. He received various assignments to remote places of the Soviet Union. His wife and two sons followed him, on his assignments. His sons, growing up as military brats, both have chosen the father′s pathway, and despite their mother′s protest, they both enrolled Ryazan Airborne School,[a] one after another.[19]

Vitaly, the eldest son (born 1975,) after graduating the airborne school in the mid 1990s, has been assigned to serve with 106th Guards Airborne Division, spent his tour of duty in Chechnya, engaging in the First Russo-Chechen Conflict, and serving up until now in the rank of Lt. Colonel, as the Chief-of-staff with 242nd Airborne Training Center, Omsk.[19]

Dmitry, the youngest son (born 1978,) after graduating the airborne school in the late 1990s, volunteered to engage in the Chechen war on terror. As the CO of a recon platoon, Khabarov jr, managed to locate and destroy two training facilities of the Chechen insurgency, intercepted and captured a major reinforcement of mercs and mujahs from various Arab states, on their way to join the rebel army, set up in the air two arms&ammo depots, and achieved several minor successes, having none of his men killed or badly wounded, while proceeding over the missions. Until one day, on his way back to compound, he was blown up by a land mine. Near dead, he was carried by his subordinates to their army base, and from there, he was evacuated by a helicopter to Mozdok, Republic of North Ossetia–Alania, and then to Moscow, where he was stationed in the same military hospital his father had been moved to, twenty years before him. He was lucky to survive, and have both his legs spared by the professionalism of army surgeons. After his recovery, he planned to go back in the action, but the military refused to have him back in service, honorary discharging him in the rank of Major, instead.[19]

Footnotes

- a Ryazan Airborne School (Russian: Рязанское высшее воздушно-десантное командное краснознамённое училище имени Ленинского комсомола,) is a still functioning four-year study facility, established on August 2, 1941, which brought up commanding officers and para specialists for military and civil organizations and agencies, such as: the Soviet Airborne Troops, and the Air Assault Troops (DShV,) airborne reconnaissance units of the Soviet Ground Forces, and Soviet Tank Corps, air assault units of the Soviet Naval Infantry, SAR-teams of the Soviet Air Forces, spetsnaz units of the Main Intelligence Directorate (GRU,) and special anti-terrorist units of the Committee for State Security (KGB.) Along with the Russian-speaking cadets, Ryazan Airborne School brought up Eastern European, South American, Caribbean, African and Asian students from the friendly socialist countries, and liberation movements. Most renowned alumni of the School are: Levan Sharashenidze, former Defense Minister of Georgia; Wojciech Jaruzelski, the last Communist leader of Poland from 1981 to 1989; and Amadou Toumani Touré, President of Mali from 2002 to 2012.

- b Salang Pass and the tunnel underneath is a high-risk military object, which could be paralyzed by a smoke grenade. An eighty eight hundred feet long, extremely narrow, with no ventilation apertures, giant tunnel could be smoked out in a matter of seconds. There were several lethal incidents during Soviet military campaign in Afghanistan, in which personal of the Soviet supply convoys has been chocked by the carbon monoxide containing in diesel exhaust, while the head truck got stuck on one of the tunnel′s ends (see Salang Tunnel fire.) It′s also been known for the deadly avalanches, which struck it time after time (see Salang avalanches.) However, while Khabarov was in charge of the Salang and its surroundings, there were no casualties from the Soviet side.

- c Shuravi or Shouravi (Persian: شوروی) is a Parsi word, which stands for “Soviets.” Contrary to other derogatory terms (e.g. yankees,) the term itself bears no negative connotation, and has been used by both, the Afghans, and Soviet militarymen in Afghanistan, referring to themselves as to Shuravi. Various terms were coined from the Afghans′ everyday language, such as Salam (short for “Peace, man!”,) Bacha (which means “Buddy”,) etc.

- d Vasily Khabarov, was a Red Army officer, and a World War II veteran, a Red Banner, and Red Star recipient. His latter assignment was a Regiment Chief-of-staff; Stepan Khabarov, was a Russian Imperial Army officer, a St. George Cross cavalier, and veteran of Russo-Japanese War, World War I, and Russian Civil War in Siberia and the Far East. His latter assignment was a Regiment Commander.

References

- ^ Hurbatov, Sergey. (July 25, 2012). "Kvachkov′s Accomplices: The Schizo Is Out, But Schizophrenia Is Still In" (in Russian). Nakanune.ru. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- ^ Lysizin, Pavel. (26 February 2013). "Russian gang convicted of coup attempt". Russian politics. Russia Today. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ Lisitsyn, Pavel. (26 February 2013). "Two Jailed in Russia Over Unlikely Coup Plot". Russia. RIA Novosti. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ "Court in Urals sentences plotters of armed mutiny". Russia News. Interfax. 26 February 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ "Accomplices in attempted armed coup given 4.5 year in prison". Courts & Legislation. Russian Legal Information Agency. 26 February 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ Lyakhovskiy, Aleksandr. (2007). "Soviet Troops Enter Afghanistan: How it began". Inside the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan and the Seizure of Kabul, December 1979 (PDF). Cold War International History Project. Vol. 51. Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. p. 44. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ a b Antonov, Alexander (1999). "Storm-333: A Story Behind The Storming Of The Tajbeg Palace In 1979". Rodina (in Russian) (2). Retrieved 2012-07-19.

- ^ a b c d e Shtepo, Valery. (2011). A Dead Officer′s Diary (in Russian). Samara. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Tukharinov, Yuri. (2005). A Secret Army Commander (in Russian). Moscow. Retrieved July 19, 2012.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Afghanistan: Heroes and Victims". Soviet Analyst. 13 (16). London: World Reports Limited: 28. 8 August 1984. ISSN 0049-1713.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help) - ^ a b Braithwaite, Rodric. Afgantsy: The Russians in Afghanistan, 1979-1989. N. Y.: Oxford University Press. p. 432. ISBN 978-0-19-983265-1.

- ^ Dynin, I. (1985). "Afghanistan: Problems of Defense of Salang Pass Recounted". Krylya Rodiny (10). a monthly journal of DOSAAF: 6–7 (80–84). ISSN 0130-2701. Retrieved August 22, 2012. Reprinted in English by the USSR Report: Military Affairs, March 13, 1986.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Trehub, Aaron (1989). "Soviet Press Coverage of the War in Afghanistan: From Cheerleading to Disenchantment / There's A War On". Report on the USSR. I (10). New York: RFE/RL, Inc.: 2. ISSN 0148-2548.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Belousov, Yuri (August 25, 2007). "Ural′s Forge of the Officership". The Red Star (in Russian). an official newspaper of the Russian Ministry of Defence. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Belousov, Yuri (February 14, 2009). "We′re Back "On The Other Bank". The Red Star (in Russian). an official newspaper of the Russian Ministry of Defence. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- ^ a b Alexandrov, Oleg (September 15, 2011). "Ministry of Defence, A Gang Of Frauds?". The Moscow Post (in Russian). Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- ^ "Prosecutor demands 5 years for defendant in attempted mutiny case". ITAR-TASS. May 17, 2012. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ^ Chalova, Yekaterina (April 9, 2012). "Afghan Veteran, Colonel Khabarov′s Detention Term Has Been Prolonged For The Third Time". PublicPost (in Russian). Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- ^ a b c Soldatenko, Boris (February 1, 2002). "Guards Ask For No Surrender!". The Red Star (in Russian). an official newspaper of the Russian Ministry of Defence. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

External links

- Frunze Military Academy alumni

- People from Yekaterinburg

- Prisoners and detainees of Russia

- Recipients of the Order of the Red Banner

- Recipients of the Order of Military Merit (Russia)

- Skydivers

- Russian academics

- Russian boxers

- Russian military personnel

- Russian mountain climbers

- Russian principals

- Russian rebels

- Soviet war in Afghanistan veterans

- 1947 births

- Living people