Battlecruiser: Difference between revisions

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

==Background== |

==Background== |

||

The battlecruiser was developed by the British [[Royal Navy]] in the first years of the 20th century as a dramatic evolution of the [[armoured cruiser]].<ref>Sondhaus, p. 199</ref><ref>Roberts, p. 13</ref> (Although,taking into account British accusations made during the [[War of 1812]] that American [[frigates]] were actually [[ships of the line]] that just looked like frigates, the concept behind the |

The battlecruiser was developed by the British [[Royal Navy]] in the first years of the 20th century as a dramatic evolution of the [[armoured cruiser]].<ref>Sondhaus, p. 199</ref><ref>Roberts, p. 13</ref> (Although,taking into account British accusations made during the [[War of 1812]] that American [[frigates]] were actually [[ships of the line]] that just looked like frigates, the concept behind the battlecruiser may have been developed a century earlier.) In the late 1890s, technical developments including the introduction of [[Krupp armour|Krupp face-hardened steel armour]] meant it was finally possible to build an armoured cruiser which could withstand the fire of 6-inch quick-firing guns. In 1896 and 1897, France and Russia, technically allies, started to build large, fast armoured cruisers which outclassed all others afloat, which could threaten trade routes, work closely with a battleship fleet and in some circumstances could even confront a battleship.<ref>Breyer, p. 47</ref><ref>Sumida p. 19</ref> Britain, which had concluded in 1892 that it needed twice as many cruisers as any potential enemy to adequately protect its empire's sea lanes, responded to the perceived threat by laying down its own large armoured cruisers. Between 1899 and 1905, it completed or laid down seven classes of this type, a total of 35 ships.<ref>Brown, p. 157–8</ref><ref>Lambert, pp. 20–22</ref><ref>Osborne, p. 61–22</ref> This building program, in turn, prompted the French and Russians to up-scale their own construction. Also, the Germans began to build large armoured cruisers for use on its overseas stations, laying down eight of them between 1897 and 1906.<ref name="Brownpp">Brown, pp. 158, 162</ref><ref>Gardiner & Gray, p. 142</ref><ref>Osborne, pp. 62, 74</ref> |

||

Both the cost and the size of the main guns for these new cruisers were rising. In the period 1889–96, the Royal Navy spent £7.3 million on new large cruisers. From 1897 to 1904, it spent £26.9 million. As for gun calibers, Japan designed its four {{sclass-|Tsukuba|cruiser}}s to carry four {{convert|12|in|mm|adj=on|0}} guns, a caliber normally ascribed to battleships, after it had used armored cruisers successfully in the [[Battle of Tsushima]] in 1905. The United States Navy had already planned its {{sclass-|Tennessee|cruiser}}s with four {{convert|10|in|mm|adj=on|0}} guns.<ref>Burr, pp. 22, 24</ref><ref>Osborne, p. 73</ref> The British also considered 10-inch and 12-inch guns for its {{sclass-|Minotaur|cruiser (1906)|0}} cruisers, the culmination of its building program, before staying with the {{convert|9.2|in|mm|adj=on|0}} guns of previous classes.<ref name="Brownpp" /> |

Both the cost and the size of the main guns for these new cruisers were rising. In the period 1889–96, the Royal Navy spent £7.3 million on new large cruisers. From 1897 to 1904, it spent £26.9 million. As for gun calibers, Japan designed its four {{sclass-|Tsukuba|cruiser}}s to carry four {{convert|12|in|mm|adj=on|0}} guns, a caliber normally ascribed to battleships, after it had used armored cruisers successfully in the [[Battle of Tsushima]] in 1905. The United States Navy had already planned its {{sclass-|Tennessee|cruiser}}s with four {{convert|10|in|mm|adj=on|0}} guns.<ref>Burr, pp. 22, 24</ref><ref>Osborne, p. 73</ref> The British also considered 10-inch and 12-inch guns for its {{sclass-|Minotaur|cruiser (1906)|0}} cruisers, the culmination of its building program, before staying with the {{convert|9.2|in|mm|adj=on|0}} guns of previous classes.<ref name="Brownpp" /> |

||

Revision as of 14:09, 11 April 2013

A battlecruiser, or battle cruiser, was a large capital ship built in the first half of the 20th century. They were similar in size and cost to a battleship, and typically carried the same kind of heavy guns, but battlecruisers generally carried less armour and were faster.

The first battlecruisers were developed in the United Kingdom in the first decade of the century, as a development of the armoured cruiser, at the same time the dreadnought succeeded the pre-dreadnought battleship. The original aim of the battlecruiser was to hunt down slower, older armoured cruisers and destroy them with heavy gunfire. However, as more and more battlecruisers were built, they increasingly became used alongside the better-protected battleships.

Battlecruisers served in the navies of Britain, Germany, Australia and Japan during World War I, most notably at the Battle of the Falkland Islands and in the several raids and skirmishes in the North Sea which culminated in a pitched fleet battle, the Battle of Jutland. British battlecruisers in particular suffered heavy losses at Jutland, where their light armour made them very vulnerable to battleship shells.

By the end of the war, capital ship design had developed with battleships becoming faster and battlecruisers becoming more and more heavily armoured, blurring the distinction between a battlecruiser and a fast battleship. The Washington Naval Treaty, which limited capital ship construction from 1922 onwards, treated battleships and battlecruisers identically, and the new generation of battlecruisers planned was scrapped under the terms of the treaty.

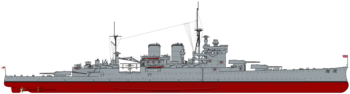

From the 1930s, only the Royal Navy continued to use 'battlecruiser' as a classification for warships, for the WWI-era capital ships that remained in the fleet. (While Japan's battlecruisers continued in service, they were significantly reconstructed and re-rated as battleships.) Nevertheless, the fast, light capital ships developed by Germany and France of the Template:Sclass- and Template:Sclass- classes, respectively, are sometimes referred to as battlecruisers.[Note 1]

The Second World War saw battlecruisers in action again, mostly consisting of modernized WWI ships and the fast battleships built in the 1930s. There was also renewed interest in large "cruiser killer" type warships, but few ever began construction, as construction of capital ships was curtailed in favor of more needed convoy escorts, aircraft carriers, and cargo ships. In the post–World War II era, the Soviet Template:Sclass- of large guided missile cruisers have also been termed "battlecruisers".

Background

The battlecruiser was developed by the British Royal Navy in the first years of the 20th century as a dramatic evolution of the armoured cruiser.[4][5] (Although,taking into account British accusations made during the War of 1812 that American frigates were actually ships of the line that just looked like frigates, the concept behind the battlecruiser may have been developed a century earlier.) In the late 1890s, technical developments including the introduction of Krupp face-hardened steel armour meant it was finally possible to build an armoured cruiser which could withstand the fire of 6-inch quick-firing guns. In 1896 and 1897, France and Russia, technically allies, started to build large, fast armoured cruisers which outclassed all others afloat, which could threaten trade routes, work closely with a battleship fleet and in some circumstances could even confront a battleship.[6][7] Britain, which had concluded in 1892 that it needed twice as many cruisers as any potential enemy to adequately protect its empire's sea lanes, responded to the perceived threat by laying down its own large armoured cruisers. Between 1899 and 1905, it completed or laid down seven classes of this type, a total of 35 ships.[8][9][10] This building program, in turn, prompted the French and Russians to up-scale their own construction. Also, the Germans began to build large armoured cruisers for use on its overseas stations, laying down eight of them between 1897 and 1906.[11][12][13]

Both the cost and the size of the main guns for these new cruisers were rising. In the period 1889–96, the Royal Navy spent £7.3 million on new large cruisers. From 1897 to 1904, it spent £26.9 million. As for gun calibers, Japan designed its four Template:Sclass-s to carry four 12-inch (305 mm) guns, a caliber normally ascribed to battleships, after it had used armored cruisers successfully in the Battle of Tsushima in 1905. The United States Navy had already planned its Template:Sclass-s with four 10-inch (254 mm) guns.[14][15] The British also considered 10-inch and 12-inch guns for its Template:Sclass- cruisers, the culmination of its building program, before staying with the 9.2-inch (234 mm) guns of previous classes.[11]

In 1904, Admiral John "Jacky" Fisher became First Sea Lord, the senior officer of the Royal Navy. He had for some time thought about the development of a new fast armoured ship. He was very fond of the "second-class battleship" Renown, a lighter, faster battleship.[16][17] As early as 1901, there is confusion in Fisher's writing about whether he saw the battleship or the cruiser as the model for future developments. This did not stop him from commissioning designs from W.H. Gard for an armored cruiser with the heaviest possible armament for use with the fleet. The design Gard submitted was for a ship between 14,000 and 15,000 tons, capable of 25 knots, armed with four 9.2-inch and twelve 7.5-inch (190 mm) guns in twin turrets and protected with 6 inches (150 mm) of armour along her belt and 9.2-inch turrets, 4 inches (100 mm) on her 7.5-inch turrets, 10-inch (250 mm) on her conning tower and up to 2.5 inches (64 mm) on her decks. However, British mainstream naval thinking between 1902 and 1904 was clearly in favour of heavily armoured battleships, rather than the fast ships that Fisher favoured.[18]

The Battle of Tsushima proved conclusively the effectiveness of heavy guns over intermediate ones and the need for a uniform main caliber on a ship for fire control. Even before this, the Royal Navy had begun to consider a shift away from the mixed-calibre armament of the 1890s pre-dreadnought to an "all-big-gun" design, and preliminary designs circulated for battleships with all 12-inch or all 10-inch guns and armoured cruisers with all 9.2-inch guns.[19] In late 1904, not long after the Royal Navy had decided to use 12-inch guns for its next generation of battleships because of their superior performance at long range, Fisher began to argue that big-gun cruisers could replace battleships altogether. The continuing improvement of the torpedo meant that submarines and destroyers would be able to destroy battleships; this in Fisher's view heralded the end of the battleship or at least compromised the validity of heavy armor protection. Nevertheless, armoured cruisers would remain vital for commerce protection[20][21][22]

Of what use is a battle fleet to a country called (A) at war with a country called (B) possessing no battleships, but having fast armoured cruisers and clouds of fast torpedo craft? What damage would (A's) battleships do to (B)? Would (B) wish for a few battleships or for more armoured cruisers? Would not (A) willingly exchange a few battleships for more fast armoured cruisers? In such a case, neither side wanting battleships is presumptive evidence that they are not of much value" – Fisher to Selborne, 20 October 1904[23]

Fisher's views were very controversial within the Royal Navy, and even given his position as First Sea Lord, he was not in a position to insist on his own approach. Thus he assembled a "Committee on Designs", consisting of a mixture of civilian and naval experts, to determine the approach to both battleship and armoured cruiser construction in future. While the stated purpose of the Committee was to investigate and report on future requirements of ships, Fisher and his associates had already made key decisions.[24] The terms of reference for the Committee were for a battleship capable of 21 knots with 12-inch guns and no intermediate calibres, capable of operating from existing docks;[25] and a cruiser capable of 25.5 knots, also with 12-inch guns and no intermediate armament, armoured like Minotaur, the most recent armoured cruiser, and also capable of working from the existing docks.[24]

First battlecruisers

Under the Selborne plan of 1902, the Royal Navy intended to start three new battleships and four armoured cruisers each year. However, in late 1904 it became clear that the 1905-6 programme would have to be considerably smaller, because of lower than expected tax revenue and the need to buy out two Chilean battleships under construction in British yards, lest they be purchased by the Russians for use in the Russo-Japanese War. These economies meant that the 1905-6 programme consisted only of one battleship, but three armoured cruisers. The battleship became the revolutionary battleship Dreadnought, and the cruisers became the three ships of the Template:Sclass-. However, Fisher later claimed that he had argued during the Committee for the cancellation of the remaining battleship.[26]

The construction of the new class was begun in 1906 and completed in 1908, delayed perhaps to allow their designs to learn from any problems with Dreadnought.[25][27] The ships fulfilled the design requirement quite closely. On a displacement similar to Dreadnought, the Invincibles were 40 feet (12 m) longer to accommodate additional boilers and engines with twice the shaft horsepower to propel them at 25 knots (46 km/h). Moreover, the new ships could maintain this speed for days, whereas pre-dreadnought battleships could not generally do so for more than an hour.[28] Armed with eight 12-inch (305 mm) Mk X guns, compared to ten on Dreadnought, they were armoured 6 or 7 inches (150 to 180 mm) thick along the side of the hull and over the gunhouses. (Dreadnought's armour, by comparison, was 11 inches (280 to 300 mm) at its thickest.[29]) The class had a very marked increase in speed, displacement and firepower compared to the most recent armoured cruisers but no more armour.[30]

While the Invincibles were to fill the same role as the armoured cruisers they succeeded, they were expected to do so more effectively. Specifically their roles were:

- Heavy Reconnaissance. Because of their power, the Invincibles could sweep away the screen of enemy cruisers to close with and observe an enemy battlefleet before using their superior speed to retire.

- Close support for the battle fleet. They could be stationed at the ends of the battle line to stop enemy cruisers harassing the battleships, and to harass the enemy's battleships if they were busy fighting battleships. Also, the Invincibles could operate as the fast wing of the battlefleet and try to outmanouevre the enemy.

- Pursuit. If an enemy fleet ran, then the Invincibles would use their speed to pursue, and their guns to damage or slow enemy ships.

- Commerce protection. The new ships would hunt down enemy cruisers and commerce raiders.[31]

Confusion about how to refer to these new battleship-size armoured cruisers set in almost immediately. Even in late 1905, before work was begun on the Invincibles, a Royal Navy memorandum refers to "large armoured ships" meaning both battleships and large cruisers. In October 1906, the Admiralty began to classify all post-Dreadnought battleships and armoured cruisers as "capital ships", while Fisher used the term "dreadnought" to refer either to his new battleships or the battleships and armoured cruisers together.[32] At the same time, the Invincible class themselves were referred to as "cruiser-battleship", "dreadnought cruiser"; the term "battlecruiser" was first used by Fisher in 1908. Finally, on 24 November 1911, Admiralty Weekly Order No. 351 laid down that "All cruisers of the “Invincible” and later types are for the future to be described and classified as “battle cruisers.” to distinguish them from the armoured cruisers of earlier date."[33]

Along with questions over the new ships' nomenclature came uncertainty about their actual role in the navy due to their lack of protection. If they were primarily to act as scouts for a potential battle fleet and hunter-killers of enemy cruisers and commerce raiders, then the seven inches of belt armour with which they had been equipped would be adequate. If, on the other hand, they were expected to reinforce a battle line of dreadnoughts with their own heavy guns, they were too thin-skinned to be safe from an enemy's heavy guns. The Invincibles were essentially extremely large, heavily armed, fast armoured cruisers. However, the validity of the armored cruiser was already in doubt. A cruiser that could have worked with the Fleet might have been a more viable option for taking over that role.[30][34]

Because of the Invincibles' size and armament, naval authorities considered them capital ships almost from their inception—an assumption that might have been inevitable. Complicating matters further was that many naval authorities, including Lord Fisher, had made overinflated assessments from the Battle of Tsushima in 1905 about the armoured cruiser's ability to survive in a battle line against enemy capital ships due to their superior speed. These assumptions had been made without taking into account the Russian Baltic Fleet's inefficiency and tactical ineptitude. By the time the term "battlecruiser" had been given to the Invincibles, the idea of their parity with battleships had been fixed in many people's minds.[30][34]

Not everyone was so convinced. Brassey's Naval Annual, for instance, stated that with vessels as large and expensive as the Invincibles, an admiral "will be certain to put them in the line of battle where their comparatively light protection will be a disadvantage and their high speed of no value."[35] Those in favor of the battlecruiser countered with two points—first, since all capital ships were vulnerable to new weapons such as the torpedo, armor had lost some of its validity; and second, because of its greater speed, the battlecruiser could determine the range at which it engaged an enemy and thus control the engagement.[36]

Battlecruisers in the Dreadnought arms race

Between the launching of the Invincibles to just after the outbreak of the First World War, the battlecruiser played a junior role in the developing dreadnought arms race, although it was never wholeheartedly adopted as the key weapon in British imperial defence, as Fisher had presumably desired. The biggest factor for this lack of acceptance was the marked change in Britain's strategic circumstances between their conception and the commissioning of the first ships. The prospective enemy for Britain had shifted from a Franco-Russian alliance with many armoured cruisers to a resurgent and increasingly belligerent Germany. Diplomatically, Britain had entered the Entente cordiale in 1904 and the Anglo-Russian Entente. Neither France nor Russia posed a particular naval threat; the Russian navy had largely been sunk or captured in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–5, while the French were in no hurry to adopt the new dreadnought battleship technology.[37] Britain also boasted very cordial relations with two of the significant new naval powers, Japan (bolstered by the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, signed in 1902 and renewed in 1905), and the USA. These changed strategic circumstances, and the great success of the Dreadnought, ensured that she rather than the Invincible became the new model capital ship. Nevertheless, battlecruiser construction played a major part in the renewed naval arms-race sparked by the Dreadnought.

For their first few years of service, the Invincibles' entirely fulfilled Fisher's vision of being able to sink any ship fast enough to catch them, and run from any ship capable of sinking them. An Invincible would also, in many circumstances, be able to take on an enemy pre-dreadnought battleship. Naval circles concurred that the armoured cruiser in its current form had come to the logical end of its development and the Invincibles were so far ahead of any enemy armoured cruiser in firepower, speed and technology that it proved difficult to justify building more or bigger cruisers.[38][39] This lead was extended by the surprise both Dreadnought and Invincible produced by having been built in secret; this prompted most other navies to delay their building programmes and radically revise their designs.[citation needed] This was particularly true for cruisers, because the details of the Invincible class were kept secret for longer; this meant that the last German armoured cruiser, Blücher was armed with only 21-centimetre (8.3 in) guns, and was no match for the new battlecruisers.[40]

The Royal Navy's early superiority in capital ships led to the rejection of a 1905–6 design that would, essentially, have fused the battlecruiser and battleship concepts into what would eventually become the fast battleship. The 'X4' design combined the full armour and armament of Dreadnought with the 25-knot (46 km/h; 29 mph) speed of Invincible. The additional cost could not be justified given the existing British lead and the new Liberal government's need for economy; the slower and cheaper Bellerophon, a relatively close copy of Dreadnought, was adopted instead.[41] The concept of the X4 would eventually be fulfilled in the Template:Sclass- and later by other navies.[42]

The next British battlecruisers were the three Template:Sclass-, slightly improved Invincibles built to fundamentally the same specification, partly due to political pressure to limit costs and partly due to the secrecy surrounding German battlecruiser construction, particularly about the heavy armour of Von der Tann.[43] This class came to be widely seen as a mistake.[44] The next generation of British battlecruisers were markedly more powerful. By 1909–10 a sense of national crisis about rivalry with Germany outweighed cost-cutting, and a naval panic resulted in the approval of a total of eight capital ships in 1909–10.[45] Fisher pressed for all eight to be battlecruisers,[46][47] but was unable to force his way; he had to settle for six battleships and two battlecruisers of the Template:Sclass-. The Lions carried eight 13.5-inch guns, the now-standard caliber of the British "super-dreadnought" battleships. Speed increased to 27 knots (50 km/h; 31 mph) and armor protection, while not as good as in German designs, was better than in previous British battlecruisers, with 9 inches on the armour belt and barbettes. The two Lions were followed by the very similar Queen Mary.[48]

By 1911 Germany had built battlecruisers of her own, and the superiority of the British ships could no longer be assured. Moreover, the German Navy did not share Fisher's view of the battlecruiser. In contrast to the British focus on increasing speed and firepower, Germany progressively improved the armour and staying power of their ships to better the British battlecruisers.[49] Von der Tann, begun in 1908 and completed in 1910, carried eight 11.1-inch guns but with 11.1-inch (280 mm) armour was far better protected than the Invincibles. The two Template:Sclass-s were quite similar but carried ten 11.1-inch guns of an improved design.[50] Seydlitz, designed in 1909 and finished in 1913, was a modified Moltke; speed increased by one knot to 26.5 knots (49.1 km/h; 30.5 mph), while armour was up to 12 inches (300 mm) thick, equivalent for the Helgoland-class battleships of just one or two years earlier. Seydlitz was Germany's last battlecruiser completed before World War I.[51]

The next step in battlecruiser design came from Japan. The Imperial Japanese Navy had been planning the Template:Sclass- ships from 1909, and was determined that, since the Japanese economy could support relatively few ships, each would be more powerful than its likely competitors. Initially the class was planned with the Invincibles as the benchmark. On learning of the British plans for Lion, and the likelihood that new U.S. Navy battleships would be armed with 14-inch (360 mm) guns, the Japanese decided to radically revise their plans and go one better. A new plan was drawn up, carrying eight 14-inch guns, and capable of 27.5 knots (50.9 km/h; 31.6 mph), thus marginally having the edge over the Lions in speed and firepower. The heavy guns were also better-positioned, being superfiring both fore and aft with no turret amidships. The armour scheme was also marginally improved over the Lions with 9 inches (230 mm) of armour on the turrets and 8 inches (200 mm) on the barbettes. The first ship in the class was built in Britain, and a further three constructed in Japan.[52] The Japanese also re-classified their powerful armoured cruisers of Template:Sclass- and Template:Sclass- classes, carrying four 12-inch guns, as battlecruisers; nonetheless, they had weaker armament and were slower.[53]

The next British battlecruiser, Tiger, was intended initially as the fourth ship in the Lion class but was redesigned substantially and greatly influenced by the Kongō.[54] She retained the eight 13.5-inch guns of her predecessors, but positioned like Kongō for better fields of fire. She was faster (making 29 knots (54 km/h; 33 mph) on trials), and carried a heavier secondary armament. Tiger was also more heavily armoured on the whole; while the maximum thickness of armour was the same at 9 inches (230 mm), the height of the main armour belt was increased.[55] Not all the desired improvements for this ship were approved, however. Her designer, Sir Tennyson d'Eyncourt, had wanted small-bore water-tube boilers and geared turbines to give her a speed of 32 knots (59 km/h), but he received no support from the authorities and the engine makers refused his request.[56]

1912 saw work begin on three more German battlecruisers of the Template:Sclass-, the first German battlecruisers to mount 12-inch guns. These excellent ships, like the Tiger and the Kongō, had their guns arranged in superfiring turrets for greater efficiency. Their armour and speed was similar to the previous Seydlitz class.[57] In 1913, the Russian Empire also began the construction of the four-ship Template:Sclass-, which were designed for service in the Baltic Sea. These ships were designed to carry twelve 14-inch (360 mm) guns, with armour up to 12 inches (300 mm) thick, and a speed of 26.6 knots (49.3 km/h; 30.6 mph). The heavy armour and relatively slow speed of these ships makes them more similar to German designs than to British ships; construction of the Borodinos was halted by the First World War and all were scrapped after the end of the Russian Civil War.[58]

World War I

In the First World War, the British and Germans used battlecruisers in several theatres. Battlecruisers formed part of the dreadnought fleets that faced each other in the North Sea, taking part in several raids and skirmishes as well as the Battle of Jutland. Battlecruisers also played an important role at the start of the War as the British fleet hunted down German commerce raiders, for instance at the Battle of the Falkland Islands, and also took part in the Mediterranean campaign.

Construction

For most of the combatants, capital ship construction was very limited during the War. Germany finished the Derfflinger class and began work on the Template:Sclass-. The Mackensens were a development of the Derfflinger class, with 13.8-inch guns and a broadly similar armour scheme, designed for 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph).[59]

In Britain, Jackie Fisher returned to the office of First Sea Lord in October 1914. His enthusiasm for big, fast ships was unabated, and he set design staff to producing a design for a battlecruiser with 15-inch guns. Because Fisher expected the next German battlecruiser to steam at 28 knots, he required the new British design to be capable of 32 knots (59 km/h; 37 mph). He planned to reorder two Template:Sclass-s, which had been approved but not yet laid down, to a new design. Fisher finally received approval for this project on 28 December 1914 and they became the Template:Sclass-. With six 15-inch guns but only 6-inch armour they were a further step forward from Tiger in firepower and speed but returned to the level of protection of the first British battlecruisers.[60]

At the same time, Fisher resorted to subterfuge to obtain another three fast, lightly armoured ships that could use several spare 15-inch gun turrets left over from battleship construction. These ships were essentially light battlecruisers, and Fisher occasionally referred to them as such, but officially they were classified as large light cruisers. This unusual designation was required because construction of new capital ships had been placed on hold, while there were no limits on light cruiser construction. They became Courageous and her sisters Glorious and Furious, and there was a bizarre imbalance between their main guns of 15 inches (380 mm) (or 18 inches (460 mm) in Furious) and their armour, which at 3 inches (76 mm) thickness was on the scale of a light cruiser. The design was generally regarded as a bizarre failure (nicknamed in the Fleet Outrageous, Uproarious and Spurious), though the later conversion of the ships to aircraft carriers was very successful.[61][62] Fisher also speculated about a new mammoth but lightly built battlecruiser that would carry 20-inch (510 mm) guns, which he termed HMS Incomparable; this never got beyond the concept stage.[63]

It is often held that the Renown and Courageous classes were designed for Fisher's plan to land troops (possibly Russian) on the German Baltic coast. Specifically, they were designed with a shallow draught, which might be important in the shallow Baltic. This is not clear-cut evidence that the ships were designed for the Baltic: it was considered that earlier ships had too much draught and not enough freeboard under operational conditions. Roberts argues that the focus on the Baltic was probably unimportant at the time the ships were designed, but was inflated later, after the disastrous Dardanelles Campaign.[64]

The final British battlecruiser design of the war was the Template:Sclass2-, which was born from a requirement for an improved version of the Queen Elizabeth battleship. The project began at the end of 1915, after Fisher's final departure from the Admiralty. While initially envisaged as a battleship, senior sea officers felt that Britain had enough battleships, but that new battlecruisers might be required to combat German ships being built (the British overestimated German progress on the Mackensen class as well as their likely capabilities). A battlecruiser design with eight 15-inch guns, 8 inches of armour and capable of 32 knots was decided on. The experience of battlecruisers at the Battle of Jutland meant that the design was radically revised and transformed again into a fast battleship concept with armour up to 12 inches thick but still capable of 31.5 knots (58.3 km/h; 36.2 mph). The first ship in the class, Hood, went ahead according to this design. The plans for her three sisters, on which little work had been done, were revised once more later in 1916 and in 1917 to improve protection.[65]

The Admiral class would have been the only British ships capable of taking on the German Mackensen class; German shipbuilding was drastically slowed by the war, and while two Mackensens were launched, none were ever completed.[66] The Germans also worked briefly on a further three ships, of the Template:Sclass-, which were modified versions of the Mackensens with 15-inch guns.[67] Work on the three additional Admirals was suspended in March 1917 to enable more escorts and merchant ships to be built to deal with the new threat from U-boats to trade. They were finally cancelled in February 1919.[66]

Goeben and the Ottoman Empire

The German battlecruiser Goeben perhaps made the most impact early in the war. Stationed in the Mediterranean, she and her escorting cruiser evaded British and French ships on the outbreak of war, and steamed to Constantinople (Istanbul) with two British battlecruisers in hot pursuit. Goeben was handed over to the Ottoman Navy, and this was instrumental in bringing the Ottoman Empire into the war on the German side as one of the Central Powers. Goeben herself, renamed Yavuz Sultan Selim, saw engagements against the Russian Navy in the Black Sea and against the British in the Aegean Sea.

Battle of Heligoland Bight

A force of British light cruisers and destroyers entered the Heligoland Bight (the part of the North Sea closest to Hamburg) to attack German shipping in August 1914, the first month of World War I. When they met opposition from German cruisers, Admiral Beatty took his squadron of four battlecruisers into the Bight and turned the battle, ultimately sinking three German light cruisers and killing their commander, Rear Admiral Leberecht Maass.

Battle of the Falklands

The original battlecruiser concept proved successful in December 1914 at the Battle of the Falkland Islands. The British battlecruisers Inflexible and Invincible did precisely the job they were intended for when they chased down and annihilated a German cruiser squadron, centered on the armoured cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, along with three light cruisers, commanded by Admiral Maximilian Graf Von Spee in the South Atlantic Ocean. Prior to the battle, the Australian battlecruiser Australia had unsuccessfully searched for the German ships in the Pacific.

Battle of Dogger Bank

During the Battle of Dogger Bank, the after turret of the German flagship Seydlitz was pierced by a British 13.5-inch shell from HMS Lion, which detonated in the working chamber. The charges being hoisted upwards were detonated, and the explosion flashed up into the turret and down into the magazine, setting fire to charges in the process of being handled. The gun crew tried to escape into the next turret, allowing the flash to spread, destroying both turrets internally. Seydlitz was saved from near-certain destruction only by emergency flooding of her after magazines. This near-disaster was due to the way that ammunition handling was arranged and was common to both German and British battleships and battlecruisers, but the lighter protection on the latter made them more vulnerable to the turret or barbette being pierced. The "working chamber" had been introduced in Formidable in 1898 and was intended to prevent such a dangerous flash, but instead made such an event more likely. The Germans learned from investigating the damaged Seydlitz and instituted improved measures to ensure ammunition handling was flash tight. The British remained unaware of the weakness, to their great misfortune at the Battle of Jutland.[citation needed]

Apart from the cordite handling, the battle was mostly inconclusive, though both Lion and Seydlitz were severely damaged. The British flagship Lion lost speed, causing her to fall behind the rest of the battleline, and Admiral Beatty was unable to effectively command for the remainder of the engagement. A British signalling error allowed the German battlecruisers to withdraw, as most of Beatty's squadron mistakenly concentrated on the crippled armoured cruiser Blücher, sinking her with great loss of life. Blücher herself was obsolete, out of all the ships in the battle, and so she had proved to be a liability to the rest of the German squadron, which was otherwise an all battlecruiser squadron.[citation needed]

Battle of Jutland

At the Battle of Jutland 18 months later, both British and German battlecruisers were employed as fleet units. The British battlecruisers became engaged with both their German counterparts, the battlecruisers, and then German battleships before the arrival of the battleships of the British Grand Fleet. The result was a disaster for the Royal Navy's battlecruiser squadrons: Invincible, Queen Mary, and Indefatigable exploded with the loss of all but a handful of their crews. This was due to the vulnerability of the working chamber, which the Germans had discovered after the near-loss of Seydlitz at Dogger Bank and had taken preventative measures against. The British ships not only had lighter armour but also lacked flash-tight ammunition handling arrangements, due in part to lack of awareness and experience, and also as it would improve their rate of fire to compensate for poor accuracy. Each was lost to a single salvo penetrating the turret and detonating in the working chamber. Beatty's flagship Lion herself was almost lost in a similar manner, save for the heroic actions of Major Harvey.[citation needed]

The better armoured and flash-tight German battlecruisers fared better, in part due to poor performance of British fuzes (their shells exploded on impact with the ships armour instead of penetrating the armour before exploding thus causing more damage). Lützow for instance only had 117 killed despite receiving more than thirty hits, though she had sufficient flooding that she was scuttled. The other German battlecruisers, Moltke, Von der Tann, Seydlitz, Derfflinger were all heavily damaged and required extensive repairs after the battle, Seydlitz barely making it home, for they had been the focus of British fire for much of the battle. No British or German battleship was sunk during the battle with the exception of the old German pre-dreadnought Pommern, the victim of torpedoes from British destroyers.[citation needed]

Interwar period

In the years immediately after World War I, Britain, Japan and the USA all began design work on a new generation of ever more powerful battleships and battlecruisers. The new burst of shipbuilding that each nation's navy desired was politically controversial and potentially economically crippling. This nascent arms race was prevented by the Washington Naval Treaty of 1922, where the major naval powers agreed to limits on capital ship numbers. The German navy was not represented at the talks; under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, Germany was not allowed any modern capital ships at all.[citation needed]

Through the 1920s and early 1930s only Britain and Japan retained battlecruisers, often modified and rebuilt from their original World War I designs. The line between the battlecruiser and the modern fast battleship became blurred; indeed, the Japanese Template:Sclass- were formally redesignated as battleships.[citation needed]

Plans in the aftermath of World War I

HMS Hood, launched in 1918, was the last First World War battlecruiser to be completed. Owing to lessons from Jutland, Hood was modified during construction; the thickness of her belt armour was increased by an average of 50 percent and extended substantially, she was given heavier deck armour, and the protection of her magazines was improved to guard against the ignition of ammunition. This was hoped to be capable of resisting her own weapons—the classic measure of a "balanced" battleship. Hood was the largest ship in the Royal Navy when completed; thanks to her great displacement, she in theory combined the firepower and armour of a battleship with the speed of a battlecruiser, causing some to refer to her as a fast battleship. However her protection was markedly less than that of the British battleships built immediately after World War I, the Template:Sclass-.[68]

The navies of Japan and the United States, not being affected immediately by the war, had time to develop new heavy guns (both upgraded their latest ships to 16-inch (410 mm) and refine their battlecruiser designs in light of combat experience in Europe. The Imperial Japanese Navy began four Template:Sclass-s. These vessels would have been of unprecedented size and power, as fast and well armoured as HMS Hood whilst carrying a main battery of ten 16-inch guns, the most powerful armament ever proposed for a battlecruiser. They were, for all intents and purposes, fast battleships—the only differences between them and the Template:Sclass-s which were to precede them were 1 inch (25 mm) less side armour and a .25 knots (0.46 km/h; 0.29 mph) increase in speed.[69] The United States Navy, which had worked on its battlecruiser designs since 1913 and watched the latest developments in this class with great care, responded with the Template:Sclass-. If completed as planned, they would have been exceptionally fast and well armed with eight 16-inch guns, but carried armour little better than the Invincibles—this after an 8000-ton increase in protection following Jutland.[70] The final stage in the post-war battlecruiser race came with the British response to the Amagi and Lexington types: four 48,000 ton G3 battlecruisers. Royal Navy documents of the period often described any battleship with a speed of over about 24 knots (44 km/h) as a battlecruiser, regardless of the amount of protective armour, although the G3 was considered by most to be a well-balanced fast battleship.[71]

The Washington Naval Treaty meant that none of these designs came to fruition. Ships that had been started were either broken up on the slipway or converted to aircraft carriers. In Japan, Amagi and Akagi were selected for conversion. Amagi was damaged beyond repair by the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake and was broken up on the slipway; the hull of one of the proposed Tosa-class battleships, Kaga, was converted in her stead.[72] The United States Navy also converted two battlecruiser hulls into aircraft carriers in the wake of the Washington Treaty: USS Lexington and USS Saratoga, although this was only considered marginally preferable to scrapping the hulls outright (the remaining four: Constellation, Ranger, Constitution and United States were indeed scrapped).[73] In Britain, Fisher's "large light cruisers," which otherwise would also have been scrapped, were converted to carriers. Furious had already been converted during the war and Glorious and Courageous were similarly converted.[74]

Rebuilding programmes

In total, nine battlecruisers survived the Washington Naval Treaty, although HMS Tiger later became a victim of the London Naval Conference of 1930 and was scrapped.[75] Because their high speed made them valuable surface units in spite of their weaknesses, most of these ships were significantly updated before World War II. Renown and Repulse were modernized significantly in the 1920s and 1930s. Between 1934 and 1936, Repulse had its bridge modified, an aircraft hangar, catapult and new gunnery equipment added and the anti-aircraft armament increased. Renown underwent a more thorough reconstruction between 1937 and 1939. Her deck armour was increased, a new set of engines and boilers fitted, an aircraft hangar and catapult added and all the armament apart from the main guns revamped totally. The bridge structure was also removed and a large bridge similar to that used in the Template:Sclass- battleships installed in its place. While conversions of this kind generally added weight to the vessel, Renown's tonnage actually decreased due to a substantially lighter power plant. Similar rebuildings planned for Repulse and Hood were cancelled due to the advent of World War II.[76]

Unable to pursue new construction, the Imperial Japanese Navy also chose to improve its existing battlecruisers of the Template:Sclass- (initially the Haruna, Kirishima, and Kongō—the Hiei only later as it had been disarmed under the terms of the Washington treaty) in two substantial reconstructions (one for Hiei). During the first of these conversions, elevation of their main guns was increased to 40 degrees, anti-torpedo bulges and 3800 tons of horizontal armour added, and a "pagoda" mast with additional command positions built up. This reduced the ships' speed to 25.9 knots (48.0 km/h; 29.8 mph). The second conversion focused on speed as they had been selected as fast escorts for aircraft carrier task forces. Completely new main engines, a reduced number of boilers and an increase in hull length by 26 ft (8.0 m) allowed them to reach up to 30 knots once again. They were reclassified as "fast battleships," although their armour and guns still fell short compared to surviving World War I–era battleships in the American or the British navies, with dire consequences during the Pacific War, when Hiei and Kirishima were easily crippled by US gunfire during actions off Guadalcanal, forcing their scuttling shortly afterwards.[77] Perhaps most tellingly, Hiei was crippled by medium-caliber gunfire from heavy and light cruisers in a close-range night engagement.[78]

There were two exceptions: Turkey's Yavuz Sultan Selim and the Royal Navy's Hood. The Turkish Navy only effected minor improvements to Yavuz Sultan Selim in the interwar period, which primarily focused on repairing wartime damage and installing new fire control systems and anti-aircraft batteries.[79] Hood was in constant service with the fleet and could not be withdrawn for an extended reconstruction. She received minor improvements over the course of the 1930s, including modern fire control systems, increased numbers of anti-aircraft guns, and in March 1941, radar.[80]

Naval rearmament

In the late 1930s navies began to build capital ships again, and during this period a number of large commerce raiders and small, fast battleships were built. While the design philosophy behind these ships was very different from that of the original battlecruisers, the term was adopted from time to time for these new ships. Germany, Italy, France and Russia all designed new vessels in this category, though only Germany and France completed them. Ultimately the Italians chose to upgrade their old battleships rather than build new battlecruisers, whereas the Russians laid down the 35,000-ton Template:Sclass-, but were unable to launch them before the Germans invaded in 1941 and captured one of the hulls. Both ships were scrapped after the war.

The German Template:Sclass-s (German:Panzerschiff – armoured ship) were built to meet the limitations of the Treaty of Versailles, which forbade Germany from exceeding 10,000 tons. There was not, however, a limitation on the caliber of main guns.[81][82] Their 12,000-ton displacement somewhat exceeded that of contemporary heavy cruiser, and their 11-inch main armament made them more powerful than heavy cruisers, which were restricted to 8-inch guns by the Washington Naval Treaty. Armor protection was only at the standards of contemporary heavy cruisers.[83][84] They were slower than cruisers and the few remaining battlecruisers, but faster than contemporary battleships. The Deutschlands' heavy armament and their superficial resemblance to battleships resulted in the term "pocket battleship", and their importance (not attributes) to the German navy led to some classifying them as capital ships.[85] Their mission was long-range commerce raiding like contemporary heavy cruisers, being able to outrun battleships while being able to outfight the heavy cruisers that could catch them, which caused some alarm among the Allies. However, this was only a temporary advantage as the Deutschlands could be outgunned and outrun by the few battlecruisers that remained, along with the new generation of fast battleships built in the 1930s.[86]

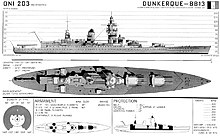

The French response to the "pocket battleships" was the Template:Sclass- in the 1930s, built to replace the Template:Sclass-s Océan and France, the latter having been wrecked in 1922.[2] Displacing 26,500 tons and armed with eight 330 mm (13 inch) guns arranged in two quadruple turrets located forward, they were significantly larger and more powerful than the pocket battleships. Their speed (30 knots) was in line with other fast battleships, and they were armoured as heavily as possible as their light displacement allowed. Planning for them actually began as early as 1924, as France had been entitled under the conditions of the Washington Treaty to lay down one new capital ship in 1927 and a second in 1929.[87] The ships' reduced size compared to earlier battleships was a result of talks between France, Britain, and Italy to limit future battleships in both displacement and armament.[88]

The Germans in turn designed their first true capital ships of the 1930s—Scharnhorst and Gneisenau—to counter the French Dunkerques. They were ordered in place of the fourth and fifth Panzerschiffe, with a third triple 28 cm turret and significantly better armour protection, on orders of Grand Admiral Erich Raeder.[89][90] The Royal Navy usually categorized these ships as battlecruisers,[91] while the German Navy referred to them as schlachtschiffe or battleships. At 32,100 long tons (32,600 t) standard displacement,[92] they were intermediate in size between Repulse or Renown and the 35,000-ton limit for battleships.[93] Their top speed of 31 knots (57 km/h; 36 mph) exceeded that of existing battlecruisers and battleships and their armoured protection was on battleship lines; their main belt was 350 mm (14 in) thick. Their armament was light for a capital ship: Scharnhorst and Gneisenau carried nine 280 mm (11-inch) guns in triple turrets.[92][94] This was a compromise since the 280 mm guns were available and developing a larger weapon and the turrets for it would have meant a two-year delay in construction. The 28 cm gun was also more politically acceptable, since a larger caliber might anger the British.[95][Note 2] The Germans subsequently designed a group of eight improved panzerschiffe, the Template:Sclass2-, and three battlecruisers, the Template:Sclass2-, though none of them were actually built.[96]

The increasing political turmoil in Asia in the 1930s prompted the Netherlands to plan a class of three battlecruisers—the Design 1047—beginning in February 1939. The ships were intended to counter the numerous Japanese cruisers that might attack the Dutch East Indies.[97] Discussions with Germany to purchase 280 mm guns and armour and obtain technical advice for these ships began the following April. When the Germans refused to release the plans for the Scharnhorst class or details about its underwater protective system, the Dutch sought additional technical advice from Italy. Work was ended by the German occupation of the Netherlands in May 1940. In general appearance and main armaments, these ships would have closely resembled the Scharnhorst class.[98]

World War II

Commerce raiding

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2011) |

In the early years of the war various German ships had a measure of success hunting merchant ships in the Atlantic. Allied battlecruisers such as Renown, Repulse, and the fast battleships Dunkerque and Strasbourg were employed on operations to hunt down the commerce-raiding German ships, but they rarely got close to their targets, Renown enjoying a brief clash against the German 11-inch battleships, scoring three non-critical hits on Gneisenau but being unable to keep up in bad weather. The one stand-up fight occurred when the battleship Bismarck was sent out as a raider and was intercepted by HMS Hood and the battleship Prince of Wales in May 1941. The elderly British battlecruiser was no match for the modern German battleship: within minutes, the Bismarck's 15-inch shells caused a magazine explosion in Hood reminiscent of the Battle of Jutland. Only three men survived.

Norwegian campaign

The Royal Navy deployed some of its battlecruisers during the Norwegian campaign in April 1940. The Gneisenau and the Scharnhorst were engaged during the Action off Lofoten by Renown in very bad weather and although they had stronger armour than their counterpart, the British ship could hit them harder and at a longer range because the German ships were having difficulty with their radars. They disengaged after Gneisenau was damaged. One of Renown's 15-inch shells passed through Gneisenau's director tower without exploding, severing electrical and communication cables as it went. The debris caused by the passing shell killed one officer and five enlisted men, and destroyed the optical rangefinder for the forward 150 mm turrets. Main battery fire control had to be shifted aft due to the loss of electrical power to the director tower. Another shell from Renown struck the aft turret of Gneisenau, knocking it out of action.

Pacific War

The first battlecruiser to see action in the Pacific War was Repulse when she was sunk near Singapore on December 10, 1941 whilst in company with Prince of Wales. She had received a refit to give extra anti-aircraft protection and extra armour between the wars. Unlike her sister Renown, Repulse did not receive a full rebuild as planned, which would have added anti-torpedo blisters. During the Sea Battle off Malaya, her speed and agility enabled her to hold her own and dodge 19 torpedoes. Without aerial cover she eventually succumbed to the continuous waves of Japanese bombers, and without enhanced underwater protection she went down quickly after a few torpedo hits.

The Japanese Kongō-class battlecruisers were significantly upgraded and re-rated as "fast battleships", and they were used extensively as carrier escorts for most of their wartime career due to their high speed. Their World War I-era armament was weaker and their upgraded armour was still thin compared to contemporary battleships. During the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal on 12 November the Hiei was sent out to bombard US positions. She suffered extensive topside damage from gunfire of US cruisers and destroyers, but, more critically, her steering gear was incapacitated by an 8-inch shell. The next day, Hiei was attacked by waves of aircraft from Guadalcanal’s American held airfield (Henderson Field), which eventually made salvage impossible, and so she was left to sink north of Savo Island. A few days later on 15 November 1942, Kirishima engaged the U.S. battleships South Dakota and Washington (both American ships were fully modern and more powerful than herself) and was sunk following mortal damage from at least nine 16-inch hits inflicted by the Washington, which disabled her forward main turrets, jammed her steering, and holed her below the waterline. In contrast South Dakota survived 42 hits (including only one 14-inch hit, but many 8-in. heavy cruiser shells), all to her superstructure, and was back in operation four months later. The Kongō survived the Battle of Leyte Gulf, but she was sunk on 21 November 1944 in the Formosa Strait by three torpedoes from the U.S. Navy submarine Sealion and poor damage control.

Large cruisers or "cruiser killers"

A late renaissance in popularity of ships between battleships and cruisers occurred on the eve of World War II. Described by some as battlecruisers but never classified as capital ships, they were variously described as "super-cruisers", "large cruisers" or even "unrestricted cruisers" and were optimized as cruiser-killers, fleet scouts and commerce raiders. The Dutch, Japanese, Soviet and American navies all planned these new classes specifically to counter the large heavy cruisers being built by their naval rivals – especially the Japanese Template:Sclass-s. The Germans also designed a class of lightly protected battlecruisers.

The first such battlecruisers were the Dutch Design 1047, desired to protect their colonies in the East Indies in the face of Japanese aggression. Never officially assigned names, these ships were designed with German and Italian assistance. While they broadly resembled the German Scharnhorst class and had the same main battery, they would have been considerably lighter armored and only protected against 8-inch (203 mm) gunfire. Although the design was mostly completed, work on the vessels never commenced as the Germans overran the Netherlands in May 1940. The first ship would have been laid down in June of that year.[99]

The Germans planned three battlecruisers of the Template:Sclass2- as part of the expansion of the Kriegsmarine (Plan Z). With six 15-inch guns, high speed, excellent range but very thin armour, they were intended as commerce raiders. Only one was ordered shortly before World War II; no work was ever done on it. No names were assigned, and they were known as O, P, and Q. The new class was not universally welcomed in the Kriegsmarine. Their abnormally-light protection gained it the derogatory nickname Ohne Panzer Quatsch (without armour nonsense) within certain circles of the Navy.[100]

The only class of these late battlecruisers actually built were the United States Navy's Template:Sclass- "large cruisers". Two of them were completed, Alaska and Guam; a third, Hawaii, was cancelled while under construction and three others, to be named Philippines, Puerto Rico and Samoa, were cancelled before they were laid down. They were classified as "large cruisers" instead of battlecruisers, and their status as non-capital ships evidenced by their being named for territories or protectorates. (Battleships, in contrast, were named after states and cruisers after cities). With a main armament of nine 12-inch (305 mm) guns in three triple turrets and a displacement of 27,000 tons, the Alaskas were twice the size of Template:Sclass-s and had guns some 50% larger in diameter. They lacked the thick armoured belt and intricate torpedo defense system of true capital ships. However, unlike most battlecruisers, they were considered a balanced design according to cruiser standards as their protection could withstand fire from their own caliber of gun, albeit only in a very narrow range band. They were designed to hunt down Japanese heavy cruisers, though by the time they entered service most Japanese cruisers had been sunk by American aircraft or submarines. Like the contemporary Template:Sclass- fast battleships, their speed ultimately made them more useful as carrier escorts and bombardment ships than as the sea combatants they were developed to be. Hawaii was 84% complete when hostilities ceased, and was laid up for years while various plans were debated to convert her large hull into a missile ship or a command vessel. She was eventually scrapped incomplete.[101]

The Japanese started designing the B64 class, which was similar to the Alaska but with 310-millimetre (12 in) guns. News of the Alaskas led them to upgrade the design, creating the B65. Armed with 356-millimetre (14 in) guns, the B65's would have been the best armed of the new breed of battlecruisers, but they still would have had only sufficient protection to keep out 8-inch shells. Much like the Dutch battlecruisers, the Japanese got as far as completing the design for the B65s, but never laid them down. By the time the designs were ready the Japanese Navy recognized that they had little use for the vessels and that their priority for construction should lie with aircraft carriers. Like the Alaskas, the Japanese did not call these ships battlecruisers, referring to them instead as super heavy cruisers.[102][103]

Cold War designs

In spite of the fact that World War II had demonstrated battleships and battlecruisers to be generally obsolete, Joseph Stalin's fondness for big gun armed warships caused the Soviet Union to plan several large cruiser classes in the late 1940s and early 1950s that would be a response for the Alaska-class vessels. In the Soviet Union they were termed "heavy cruisers" (thyazholyi kreyser).[104]

The fruits of this program were the Project 82 (Stalingrad) cruisers, of 36,500 tonnes (35,900 long tons) standard load (42,300 tonnes (41,600 long tons) full load), nine 305 mm guns and a speed of 35 knots (65 km/h; 40 mph). Three ships were laid in 1951–52, but they were canceled in April 1953 after Stalin's death. Only the central armoured hull section of the first ship, Stalingrad, was launched in 1954 and then used as a target.[105]

The Soviet Template:Sclass- was classified as battlecruisers in the 1996–7 edition of Jane's Fighting Ships. This classification arises from their nearly 26,000-tonne (26,000-long-ton) displacement, which is roughly equal to that of a World War I battleship and more than twice the displacement of contemporary cruisers, and the fact that they possess more firepower than nearly every other surface ship. The Kirov class lacks the armour that distinguishes battlecruisers from ordinary cruisers and they are classified as Tyazholyy Atomnyy Raketny Kreyser (Heavy Nuclear-powered Missile Cruiser) in Russia. Four members of the class were completed, but due to post-Soviet Union budget constraints only the Petr Velikiy is operational with the Russian Navy, though the Admiral Nakhimov is undergoing modernization and overhaul.[106]

See also

- List of sunken battlecruisers

- Protected cruiser

- Armoured cruiser

- Cruiser

- List of cruisers

- Crossing the T

References

Notes

- ^ The German Template:Sclass-s and Template:Sclass-s and the French Template:Sclass-s are all sometimes referred to as battlecruisers. Since neither their operators nor a significant number of naval historians did/do not classify them as such, they are not discussed in this article.[1][2][3]

- ^ While discussions were held between the Kriegsmarine and Krupp in January 1935 about the possibility of fitting 380 mm twin turrets into the 280 mm triple barbettes of Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, it is not clear whether this change was planned from the outset. When plans were made in 1942 to modify Gneisenau, it was found that, with proper reinforcement and the change of a few minor dimensions, this could actually be done. Until then, the matter had apparently not been pursued in detail (Breyer, p. 295).

Footnotes

- ^ Koop & Schmolke, p. 4

- ^ a b Gardiner & Chesneau, p. 259

- ^ Bidlingmaier, pp. 73–74

- ^ Sondhaus, p. 199

- ^ Roberts, p. 13

- ^ Breyer, p. 47

- ^ Sumida p. 19

- ^ Brown, p. 157–8

- ^ Lambert, pp. 20–22

- ^ Osborne, p. 61–22

- ^ a b Brown, pp. 158, 162

- ^ Gardiner & Gray, p. 142

- ^ Osborne, pp. 62, 74

- ^ Burr, pp. 22, 24

- ^ Osborne, p. 73

- ^ Roberts, p. 15

- ^ Macaky, pp. 212–213

- ^ Breyer, p. 48

- ^ Roberts, pp. 16–17

- ^ Mackay, pp. 324–325

- ^ Roberts, pp. 17–18

- ^ Sumida, p. 52

- ^ quoted in Sumida, p. 52

- ^ a b Roberts, p.19

- ^ a b Breyer, p. 115

- ^ Sumida, p. 55

- ^ Roberts, pp. 24–25

- ^ Burr, pp. 7–8

- ^ Breyer, pp. 114–117

- ^ a b c Gardiner & Gray, p. 24

- ^ Roberts, p. 18

- ^ Mackay, pp. 325–326

- ^ Admiralty Weekly Orders. 351.—Description and Classification of Cruisers of the “Invincible” and Later Types. ADM 182/2, quoted at The Dreadnought Project: The Battle Cruiser in the Royal Navy.

- ^ a b Massie, p. 494

- ^ As quoted in Massie, pp. 494–495

- ^ Friedman, p. 10

- ^ Sondhaus, pp. 200–201

- ^ Roberts, p. 25

- ^ Mackay pp. 324–325

- ^ Staff, pp. 3–4

- ^ Roberts, p. 26

- ^ Breyer, pp. 61–62

- ^ Roberts, pp. 28–29

- ^ Brown, p. 57

- ^ Sondhaus, p. 203

- ^ Roberts, p. 32

- ^ Brown, p.58

- ^ Roberts, pp. 31–33

- ^ Sondhaus, pp. 202–203

- ^ Breyer, pp. 269–272

- ^ Breyer, pp. 267, 272

- ^ Evans and Peattie, pp. 161–163

- ^ Gardiner & Gray, p. 233

- ^ Breyer, p. 135

- ^ Roberts, pp. 37–38

- ^ Breyer, p. 136

- ^ Breyer, p. 277–278

- ^ Breyer, p. 399

- ^ Breyer, pp. 283–284

- ^ Roberts, pp. 46–47

- ^ Roberts, pp. 50–52

- ^ Brown, pp. 97–98

- ^ Breyer, p. 172

- ^ Roberts, p. 51

- ^ Roberts, pp. 58–61

- ^ a b Roberts, pp. 60–61

- ^ Gröner, pp. 58–59

- ^ Breyer, p. 168

- ^ Breyer, p. 353

- ^ Breyer, p. 234

- ^ Gardiner & Gray, pp. 41–42

- ^ Gardiner & Gray, p. 235

- ^ Gardiner & Gray, p. 119

- ^ Gardiner & Gray, p. 40

- ^ Burt, pp. 23, 51

- ^ Breyer, pp. 157–158, 172

- ^ Breyer, pp. 339–340

- ^ Stille, pp. 19–20

- ^ Gardiner & Chesneau, p. 406

- ^ Konstam, pp. 33–34

- ^ Preston, p. 117

- ^ Whitley, p. 64

- ^ Gardiner & Chesneau, p. 227

- ^ Bidlingmaier, p. 73

- ^ Gardiner & Brown, p.25

- ^ Bidlingmaier, pp. 73–74

- ^ Breyer, p. 433

- ^ Gardiner & Chesneau, p. 255

- ^ Gröner, p. 63

- ^ Garzke & Dulin, p. 128

- ^ Van der Vat, p. 82

- ^ a b Gröner, p. 31

- ^ Gardiner & Gray, p. 38

- ^ Gardiner & Chesneau, p. 225

- ^ Breyer, pp. 294–295

- ^ Gröner, pp. 64, 68

- ^ Gardiner & Chesneau, p. 388

- ^ Breyer, p. 454

- ^ Noot, pp. 243, 249, 268

- ^ Garzke & Dulin, pp. 353–54, 363

- ^ "Hawaii". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ Jentschura, Jung & Mickel, p. 40

- ^ Garzke & Dulin, pp. 86–87

- ^ McLaughlin, pp. 104–06

- ^ McLaughlin, pp. 116, 121–22

- ^ "Project 1144.2 Orlan Kirov class Guided Missile Cruiser (Nuclear Powered)". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

References

- Bidlingmaier, Gerhard (1971). "KM Admiral Graf Spee". Warship Profile 4. Windsor, UK: Profile Publications. pp. 73–96. OCLC 20229321.

- Breyer, Siegfried (1973). Battleships and Battle Cruisers 1905–1970. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0385072473.

- Brooks, John (2005). Dreadnought Gunnery at the Battle of Jutland: The Question of Fire Control. London: Routledge, Frank Cass Publishers. ISBN 0-7146-5702-6.

- Burr, Lawrence (2006). British Battlecruisers 1914–1918. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-008-6.

- Churchill, Winston (1986). The Second World War: The Gathering Storm. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-395-41055-X.

- Evans, David C.; Peattie, Mark R. (1997). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-192-7.

- Friedman, Norman (2008). Naval Firepower: Battleship Guns and Gunnery in the Dreadnought Era. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-555-4.

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1984). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1922. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-907-3.

- Gardiner, Robert; Chesneau, Roger (1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships, 1922–1946. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-913-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gardiner, Robert; Brown, David (2004). The Eclipse Of The Big Gun: The Warship 1906-1945. London: Conway. ISBN 0-85177-953-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Garzke, William H.; Dulin, Robert O. (1985). Battleships: Axis and Neutral Battleships in World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-101-0.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-790-9.

- Hough, Richard (1964). Dreadnought: A History of the Modern Battleship. New York: MacMillan. ISBN 64-22602.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - Jentschura, Hansgeorg; Jung, Dieter; Mickel, Peter (1977). Warships of the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1869–1945. Annapolis, Maryland: United States Naval Institute. ISBN ISBN 0-87021-893-X.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - Konstam, Angus (2003). British Battlecruisers 1939–45. Oxford, UK: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84176-633-1.

- Koop, Gerhard; Schmolke, Klaus-Peter (1998). Battleship Scharnhorst. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-772-4.

- Lambert, Nicholas (2002). Sir John Fisher's Naval Revolution. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-492-3.

- Massie, Robert K. (1991). Dreadnought: Britain, Germany and the coming of the great war. New York: Random House. ISBN 0-394-52833-6.

- Mackay, Ruddock F. (1973). Fisher of Kilverstone. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198224095.

- McLaughlin, Stephen (2006). "Project 82: The Stalingrad Class". In Jordan, John (ed.). Warship 2006. London: Conway. pp. 102–123. ISBN 978-1-84486-030-2.

- Noot, Lt. Jurrien S. (1980). "Battlecruiser: Design studies for the Royal Netherlands Navy 1939–40". Warship International. XVII (3). Toledo, Ohio: International Naval Research Organization: 242–273.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - Osborne, Eric F. (2004). Cruisers and Battle Cruisers: An Illustrated History of Their Impact. Santa Barbara, California: ABC CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-369-9.

- Preston, Antony (2002). The World's Worst Warships. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-754-6.

- Roberts, John (1997). Battlecruisers. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-068-1.

- Staff, Gary (2006). German Battlecruisers: 1914–1918. Oxford, UK: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-009-3. OCLC 64555761.

- Stille, Mark (2008). Imperial Japanese Navy Battleship 1941–1945. Oxford, UK: Osprey Books. ISBN 978-1-84603-280-6.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (2001). Naval Warfare, 1815–1914. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-21478-0.

- Sumida, Jon T. (1993). In Defense of Naval Supremacy: Financial Limitation, Technological Innovation and British Naval Policy, 1889–1914. London: Routledge. ISBN 0044451040.

- Vandervat, Dan (1988). The Atlantic Campaign. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-015967-2.

- Whitley, M. J. (1998). Battleships of World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-184-4.