Pyramidology: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Undid revision 596895312 by (talk); not WP:OR, this was covered by Kepler, Taylor, and others (see article on Golden Ratio, for example) |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

===Metrological=== |

===Metrological=== |

||

Metrological Pyramidology is tracable to the 17th century. [[John Greaves]] professor of Astronomy, at Oxford, in his ''Pyramidographia'' (1646) first theorised that the Great Pyramid at Giza was constructed by a geometric cubit which he called the "Memphis cubit". Further research papers on Greaves' hypothetical cubit were published by the antiquarian [[Thomas Birch]] in 1737.<ref>''Miscellaneous Works of Mr. John Greaves'', Vol. II, Printed by J. Hughs, for J. Brindley, and C. Corbett, 1737, p. 405.</ref><ref>''Life and Work at the Great Pyramid during the months of January, February, March, and April, A. D. 1865'', C. Piazzi Smyth Edmonston and Douglas, 1867, p. 341.</ref> [[Isaac Newton]] used Greaves' measurements of the Great Pyramid and published them in a paper entitled "A Dissertation upon the Sacred Cubit" from which he linked the "Memphis cubit" to the hypothetical sacred cubit of the Hebrews.<ref>http://www.newtonproject.sussex.ac.uk/view/texts/normalized/THEM00276</ref> |

Metrological Pyramidology is tracable to the 17th century. [[John Greaves]] professor of Astronomy, at Oxford, in his ''Pyramidographia'' (1646) first theorised that the Great Pyramid at Giza was constructed by a geometric cubit which he called the "Memphis cubit". Further research papers on Greaves' hypothetical cubit were published by the antiquarian [[Thomas Birch]] in 1737.<ref>''Miscellaneous Works of Mr. John Greaves'', Vol. II, Printed by J. Hughs, for J. Brindley, and C. Corbett, 1737, p. 405.</ref><ref>''Life and Work at the Great Pyramid during the months of January, February, March, and April, A. D. 1865'', C. Piazzi Smyth Edmonston and Douglas, 1867, p. 341.</ref> [[Isaac Newton]] used Greaves' measurements of the Great Pyramid and published them in a paper entitled "A Dissertation upon the Sacred Cubit" from which he linked the "Memphis cubit" to the hypothetical sacred cubit of the Hebrews.<ref>http://www.newtonproject.sussex.ac.uk/view/texts/normalized/THEM00276</ref> |

||

The ratio of the perimeter to height of 1760/280 cubits equates to 2[[pi|π]] to an accuracy of better than 0.05% (corresponding to the well-known approximation of π as 22/7). Some Egyptologists consider this to have been the result of deliberate design proportion. Verner wrote, "We can conclude that although the ancient Egyptians could not precisely define the value of π, in practice they used it".<ref>Verner (2003) p.70.</ref> Petrie, author of ''Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh'' concluded: "but these relations of areas and of circular ratio are so systematic that we should grant that they were in the builder's design".<ref>Petrie Wisdom of the Egyptians 1940: 30</ref> Others have argued that the Ancient Egyptians had no concept of [[pi]] and would not have thought to encode it in their monuments. They believe that the observed pyramid slope may be based on a simple [[seked]] slope choice alone, with no regard to the overall size and proportions of the finished building.<ref name=Rossi>Rossi, Corina Architecture and Mathematics in Ancient Egypt Cambridge University Press. 2007 ISBN 978-0-521-69053-9</ref> |

|||

With similar accuracy, the ratio of the face-centered diagonal F (~356.089 cubits) with adjoining "leg" to center-point (220 cubits) is the [[golden ratio]] (phi) itself while that of F with the height (280 cubits) the square root of phi. |

|||

===John Taylor=== |

===John Taylor=== |

||

In his work ''The great pyramid; why was it built: & who built it?'' (1859) [[John Taylor (1781-1864)|John Taylor]] described a possible connection with the dimensions of the pyramid and the [[golden ratio]] (see [[Kepler triangle]]). He also proposed that the |

|||

inch used to build the Great Pyramid (see [[pyramid inch]]) |

inch used to build the Great Pyramid (see [[pyramid inch]]) was 1/25 of the "sacred cubit" (whose existence had earlier been postulated by Isaac Newton). Taylor was also the first to claim the pyramid was divinely inspired, contained a revelation and was built not by the Egyptians, but instead the Hebrews pointing to Biblical passages (Is. 19: 19-20; Job 38: 5-7) to support his theories.<ref>''A Study in Pyramidology, E. Raymond Capt, Hoffman Printing, 1996 ed. p. 34</ref> For this reason Taylor is often credited as being the "founder of pyramidology". [[Martin Gardner]] noted: |

||

{{cquote|[...] it was not until 1859 that Pyramidology was born. This was the year that John Taylor, an eccentric partner in a London publishing firm, issued his ''The Great Pyramid: Why was it Built? And Who Built it?'' [...] Taylor never visited the Pyramid, but the more he studied its structure, the more he became convinced that its architect was not an Egyptian, but an Israelite acting under divine orders. Perhaps it was Noah himself."<ref name="gardner"/>}} |

{{cquote|[...] it was not until 1859 that Pyramidology was born. This was the year that John Taylor, an eccentric partner in a London publishing firm, issued his ''The Great Pyramid: Why was it Built? And Who Built it?'' [...] Taylor never visited the Pyramid, but the more he studied its structure, the more he became convinced that its architect was not an Egyptian, but an Israelite acting under divine orders. Perhaps it was Noah himself."<ref name="gardner"/>}} |

||

Revision as of 16:38, 15 March 2014

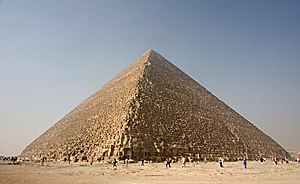

Pyramidology is a term used, sometimes disparagingly, to refer to various pseudoscientific speculations regarding pyramids, most often the Giza Necropolis and the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt.[1] Some "pyramidologists" also concern themselves with the monumental structures of pre-Columbian America (such as Teotihuacan, the Mesoamerican Maya civilization, and the Inca of the South American Andes), and the temples of Southeast Asia.

Pyramidology is regarded as pseudoscience by scientists today, who regard such hypotheses as sensationalist, inaccurate and/or wholly deficient in empirical analysis and application of the scientific method.

Some pyramidologists claim that the Great Pyramid of Giza has encoded within it predictions for the exodus of Moses from Egypt,[2] the crucifixion of Jesus,[2] the start of World War I,[3][4] the founding of modern-day Israel in 1948, and future events including the beginning of Armageddon; discovered by using what they call "pyramid inches" to calculate the passage of time (one British inch = one solar year).

The study of Pyramidology reached its peak by the early 1980s. Interest was rekindled when in 1992 and 1993 Rudolf Gantenbrink sent a miniature remote controlled robot rover, known as upuaut, up one of the air shafts in the Queen's Chamber. He discovered the shaft closed off by a stone block with decaying copper hooks attached to the outside. In 1994 Robert Bauval published the book The Orion Mystery attempting to prove that the Pyramids on the Giza plateau were built to mimic the stars in the belt of the constellation Orion, a claim that came to be known as the Orion correlation theory. Both Gantenbrink and Bauval have spurred on greater interest in pyramidology.[5][6]

Types of pyramidology

The main types of pyramidological accounts involve one or more aspects which include:

- metrological: theories regarding the construction of the Great Pyramid of Giza by hypothetical geometric measurements

- numerological: theories that the measurements of the Great Pyramid and its passages have esoteric significance, and that their geometric measurements contain some encoded message. This form of pyramidology is popular within Christian Pyramidology (e.g. British Israelism and Bible Students).

- "pyramid power": claims originating in the late 1960s that pyramids as geometrical shapes possess supernatural powers

- pseudoarchaeological: varying theories that deny the pyramids were built to serve exclusively as tombs for the Pharaohs; alternative explanations regarding the construction of the pyramids (for example the use of long-lost knowledge; anti-gravity technology, etc...); and hypotheses that they were built by someone other than the historical Ancient Egyptians (e.g. early Hebrews, Atlanteans, or even extra-terrestrials)

History

Metrological

Metrological Pyramidology is tracable to the 17th century. John Greaves professor of Astronomy, at Oxford, in his Pyramidographia (1646) first theorised that the Great Pyramid at Giza was constructed by a geometric cubit which he called the "Memphis cubit". Further research papers on Greaves' hypothetical cubit were published by the antiquarian Thomas Birch in 1737.[7][8] Isaac Newton used Greaves' measurements of the Great Pyramid and published them in a paper entitled "A Dissertation upon the Sacred Cubit" from which he linked the "Memphis cubit" to the hypothetical sacred cubit of the Hebrews.[9]

The ratio of the perimeter to height of 1760/280 cubits equates to 2π to an accuracy of better than 0.05% (corresponding to the well-known approximation of π as 22/7). Some Egyptologists consider this to have been the result of deliberate design proportion. Verner wrote, "We can conclude that although the ancient Egyptians could not precisely define the value of π, in practice they used it".[10] Petrie, author of Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh concluded: "but these relations of areas and of circular ratio are so systematic that we should grant that they were in the builder's design".[11] Others have argued that the Ancient Egyptians had no concept of pi and would not have thought to encode it in their monuments. They believe that the observed pyramid slope may be based on a simple seked slope choice alone, with no regard to the overall size and proportions of the finished building.[12]

With similar accuracy, the ratio of the face-centered diagonal F (~356.089 cubits) with adjoining "leg" to center-point (220 cubits) is the golden ratio (phi) itself while that of F with the height (280 cubits) the square root of phi.

John Taylor

In his work The great pyramid; why was it built: & who built it? (1859) John Taylor described a possible connection with the dimensions of the pyramid and the golden ratio (see Kepler triangle). He also proposed that the inch used to build the Great Pyramid (see pyramid inch) was 1/25 of the "sacred cubit" (whose existence had earlier been postulated by Isaac Newton). Taylor was also the first to claim the pyramid was divinely inspired, contained a revelation and was built not by the Egyptians, but instead the Hebrews pointing to Biblical passages (Is. 19: 19-20; Job 38: 5-7) to support his theories.[13] For this reason Taylor is often credited as being the "founder of pyramidology". Martin Gardner noted:

[...] it was not until 1859 that Pyramidology was born. This was the year that John Taylor, an eccentric partner in a London publishing firm, issued his The Great Pyramid: Why was it Built? And Who Built it? [...] Taylor never visited the Pyramid, but the more he studied its structure, the more he became convinced that its architect was not an Egyptian, but an Israelite acting under divine orders. Perhaps it was Noah himself."[1]

Christian pyramidology

British Israelism

Taylor in turn influenced the Astronomer Royal of Scotland Charles Piazzi Smyth, F.R.S.E., F.R.A.S., who made numerous numerological calculations on the pyramid and published them in a 664-page book Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid (1864) followed by Life, and Work in the Great Pyramid (1867). These two works fused pyramidology with British Israelism and Smyth first linked the hypothetical pyramid inch to the British metric system.[14]

Smyth's theories were later expanded upon by early 20th century British Israelites such as Colonel Garnier (Great Pyramid: Its Builder & Its Prophecy, 1905), who began to theorise that chambers within the Great Pyramid contain prophetic dates which concern the future of the British, Celtic, or Anglo-Saxon peoples. However this idea first originated with Robert Menzies, an earlier correspondent of Smyth's.[15] David Davidson with H. Aldersmith wrote The Great Pyramid, Its Divine Message (1924) and further introduced the idea that Britain's chronology (including future events) may be unlocked from inside the Great Pyramid. This theme is also found in Basil Stewart's trilogy on the same subject: Witness of the Great Pyramid (1927), The Great Pyramid, Its Construction, Symbolism and Chronology (1931) and History and Significance of the Great Pyramid... (1935). More recently a four-volume set entitled Pyramidology was published by British Israelite Adam Rutherford (released between 1957–1972).[16] British Israelite author E. Raymond Capt also wrote Great Pyramid Decoded in 1971 followed by Study in Pyramidology in 1986.

Joseph A. Seiss

Joseph Seiss was a Lutheran minister who was a proponent of pyramidology. He wrote A Miracle in Stone: or, The Great Pyramid of Egypt in 1877. His work was popular with contemporary evangelical Christians.[17]

Charles Taze Russell

In 1891 pyramidology reached a global audience when it was integrated into the works of Charles Taze Russell, founder of the Bible Student movement.[18] Russell however denounced the British-Israelite variant of pyramidology in an article called The Anglo-Israelitish Question .[19] Adopting Joseph Seiss's designation that the Great Pyramid of Giza was "the Bible in stone" Russell taught that it played a special part in God's plan during the "last days" basing his interpretation on Isaiah 19:19-20 which says - "In that day shall there be an altar (pile of stones) to the Lord in the midst of the land of Egypt, and a pillar (Hebrew matstebah, or monument) at the border thereof to the Lord. And it shall be for a sign, and for a witness unto the Lord of Hosts in the land of Egypt."[20] Two brothers, archaeologists John and Morton Edgar, as personal associates and supporters of Russell, wrote extensive treatises on the history, nature, and prophetic symbolism of the Great Pyramid in relation to the then known archaeological history, along with their interpretations of prophetic and Biblical chronology. They are best known for their two-volume work Great Pyramid Passages and Chambers, published in 1910 and 1913.[21]

Although most Bible Student groups continue to support and endorse the study of pyramidology from a Biblical perspective, the Bible Students associated with to the Watchtower Society, who choose ’Jehovah's Witnesses’ as their new name in 1931, have abandoned pyramidology entirely since 1928.[22][23]

Pyramid Power

Another set of speculations concerning pyramids have centered upon the possible existence of an unknown energy concentrated in pyramidical structures.[24]

Pyramid energy was popularized in the early 1970s, particularly by New Age authors such as Patrick Flanagan (Pyramid Power: The Millennium Science, 1973), Max Toth and Greg Nielsen (Pyramid Power, 1974) and Warren Smith (Secret Forces of the Pyramids, 1975). These works focused on the alleged energies of pyramids in general not solely the Egyptian pyramids, Toth and Nielson for example reported experiments where "seeds stored in pyramid replicas germinated sooner and grew higher".[25]

Pseudoarchaeology

Lewis Spence in his An Encyclopaedia of Occultism (1920) summed up on the earliest of pseudoarcheological claims on the ancient Egyptian pyramids as follows:

"...in the 1880s, Ignatius Donnelly had suggested that the Great Pyramid had been built by the descendants of the Atlanteans. That idea was picked up in the 1920s by Manly Palmer Hall who went on to suggest that they were the focus of the ancient Egyptian wisdom schools. Edgar Cayce built upon Hall's speculations.[26]

Ignatius Donnelly and later proponents of the hyperdiffusionist view of history claimed that all pyramid structures across the world had a common origin. Donelly claimed this common origin was in Atlantis.[27] While Grafton Elliot Smith claimed Egypt, writing: "Small groups of people, moving mainly by sea, settled at certain places and there made rude imitations of the Egyptian monuments of the Pyramid Age."[28]

Ancient astronauts

Several proponents of ancient astronauts claim that the Great Pyramid of Giza was constructed by extraterrestrial beings, or influenced by them (e.g., through their advanced technology).[29] Proponents include Erich von Däniken, Robert Charroux, W. Raymond Drake, and Zecharia Sitchin. According to Eric Von Daniken, the Great Pyramid has advanced numerological properties which could not have been known to the ancient Egyptians and so must have been passed down by extraterrestrials: "...the height of the pyramid of Cheops, multiplied by a thousand million—98,000,000 miles—corresponds approximately to the distance between the Earth and the sun".[30]

Orion correlation theory

Robert Bauval and Graham Hancock (1996) have both suggested that the 'ground plan' of the three main Egyptian pyramids was physically established in c. 10,500 BC, but that the pyramids were built around 2,500 BC. This theory was based on their initial claims regarding the alignment of the Giza pyramids with Orion ("…the three pyramids were a terrestrial map of the three stars of Orion's belt"— Hancock's Fingerprints of the Gods, 1995, p. 375) are later joined with speculation about the age of the Great Sphinx (Hancock and Bauval, Keeper of Genesis, published 1996, and in 1997 in the U.S. as The Message of the Sphinx).

Advanced technology

Linked to the pseudoarchaeological ancient astronaut theory and Orion correlation theory are related claims that the Great Pyramid was constructed by the use of an advanced lost technology. Proponents of this theory often link this hypothetical advanced technology to extraterrestrials but also Atlanteans, Lemurians or a legendary lost race.[31][32][33] Notable proponents include: Christopher Dunn and David Hatcher Childress. Graham Hancock also in his book Fingerprints of the Gods assigned the 'ground plan' of the three main Egyptian pyramids in his theory to an advanced progenitor civilization which possessed advanced technology.

Alan F. Alford

Author Alan F. Alford interprets the entire Great Pyramid in the context of ancient Egyptian religion. Alford takes as his starting point the golden rule that the pharaoh had to be buried in the earth, i.e. at ground level or below, and this leads him to conclude that Khufu was interred in an ingeniously concealed cave whose entrance is today sealed up in the so-called Well Shaft adjacent to a known cave called the Grotto.[34] He has lobbied the Egyptian authorities to explore this area of the pyramid with ground penetrating radar.[35]

The cult of creation theory also provided the basis for Alford's next idea: that the sarcophagus in the King's Chamber - commonly supposed to be Khufu's final resting place - actually enshrined iron meteorites.[36] He maintains, by reference to the Pyramid Texts, that this iron was blasted into the sky at the time of creation, according to the Egyptians' geocentric way of thinking. The King's Chamber, with its upward inclined dual 'airshafts', was built to capture the magic of this mythical moment.[37]

Alford's most speculative idea is that the King's Chamber generated low frequency sound via its 'airshafts', the purpose being to re-enact the sound of the earth splitting open at the time of creation.[38][39]

21st century, India

Various spiritual organizations in India, have used pyramids as a means to promote theories of their potency. Numerous papers have been published in an Indian journal of science called "Indian Journal of Traditional Knowledge" by Council of Scientific and Industrial Research.[40]

Criticism

Flinders Petrie

The renowned Egyptologist Flinders Petrie in 1880 went to Egypt to perform new measurements of the Great Pyramid and wrote that he found that the pyramid was several feet smaller than previously believed by John Taylor and Charles Piazzi Smyth.[41] Flinders therefore claimed that the hypothetical pyramid inch of the pyramidologists had no basis in truth and published his results in "The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh" (1883), writing: "there is no authentic example, that will bear examination, of the use or existence of any such measure as a 'Pyramid inch,' or of a cubit of 25.025 British inches." Proponents of the pyramid inch, especially British Israelites responded to Petrie's discoveries and claimed to have found flaws in them.[42] Petrie refused to respond to these criticisms, claiming he had disproved the pyramid inch and compared continuing proponents to "flat earth believers":

[...] It is useless to state the real truth of the matter, as it has no effect on those who are subject to this type of hallucination. They can but be left with the flat earth believers and other such people to whom a theory is dearer than a fact.[43]

Allan Alter and Dale Simmons

The Toronto Society for Psychical Research organized a research team consisting of Allan Alter (B.Sc.Phm) and Dale Simmons (Dip. Engr. Tech) to explore claims made in Pyramid Power literature that pyramids could preserve better organic matter.[44] Extensive tests showed that pyramid containers "are no more effective than those of other shapes in preserving and dehydrating organic material."[45][46]

Mainstream Egyptology

In 1964 Barbara Mertz, reflecting the views of the scientific establishment, reported another term for pyramidologists:

Even in modern times when people, one would think, should know better, the Great Pyramid of Giza has proved a fertile field for fantasy. The people who do not know better are the Pyramid mystics, who believe that the Great Pyramid is a gigantic prophecy in stone, built by a group of ancient adepts in magic. Egyptologists sometimes uncharitably refer to this group as 'Pyramidiots,' but the school continues to flourish despite scholarly anathemas.[47]

The term pyramidiot is said to have been coined by Leonard Cottrell, whose 1956 book The Mountains of Pharaoh included a chapter entitled "The Great Pyramidiot" about Piazzi Smyth's theories.[48]

See also

References

- ^ a b Martin Gardner, Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science, Dover, 1957; a reprint of In the Name of Science, G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1952.

- ^ a b Capt, E. Raymond ''The Great Pyramid Decoded Artisan Publishers (June 1978) ISBN 978-0-934666-01-5 pp. 76-78

- ^ Davidson, D.; H.W. Badger Great Pyramid & Talks on the Great Pyramid 1881 Kessinger Publishing Co (28 April 2003) ISBN 978-0-7661-5016-4 p.19

- ^ Collier, Robert Gordon Something to Hope For 1942 Kessinger Publishing Co (15 Oct 2004) ISBN 978-1-4179-7870-0 p.17

- ^ The Upuaut Project

- ^ Bauval, Robert; Gilbert, Adrian The Orion Mystery: Unlocking the Secrets of the Pyramids

- ^ Miscellaneous Works of Mr. John Greaves, Vol. II, Printed by J. Hughs, for J. Brindley, and C. Corbett, 1737, p. 405.

- ^ Life and Work at the Great Pyramid during the months of January, February, March, and April, A. D. 1865, C. Piazzi Smyth Edmonston and Douglas, 1867, p. 341.

- ^ http://www.newtonproject.sussex.ac.uk/view/texts/normalized/THEM00276

- ^ Verner (2003) p.70.

- ^ Petrie Wisdom of the Egyptians 1940: 30

- ^ Rossi, Corina Architecture and Mathematics in Ancient Egypt Cambridge University Press. 2007 ISBN 978-0-521-69053-9

- ^ A Study in Pyramidology, E. Raymond Capt, Hoffman Printing, 1996 ed. p. 34

- ^ M. Reisenauer, "The battle of the standards" : Great Pyramid metrology and British identity, 1859-1890, The Historian, v. 65 no. 4 (Summer 2003) p. 931–978; E. F. Cox, The International Institute: First organized opposition to the metric system, Ohio History, v. 68, 54–83

- ^ The idea of associating lengths in the pyramid with dates in history was suggested to Smyth by Robert Menzies, [Smyth, 1864, appendix II].

- ^ Adam Rutherford, Pyramidology Books 1, 2, and 3, C. Tinling & Co Ltd London, Liverpool and Prescot 1961, 1962 & 1966.

- ^ The Great Pyramid of Egypt, Miracle in Stone: Secrets and Advanced Knowledge (2007 Reprint) by Joseph Augustus Seiss, Forgottenbooks.com, pages vii-x.

- ^ Jehovah's Witnesses, Edmond C. Gruss, Xulon Press, 2001, pp. 210-212.

- ^ Thy Kingdom Come, Charles Taze Russell, C-291, Oakland Co. Bible Students, 2000.

- ^ Charles Taze Russell (1890). Thy Kingdom Come. Watchtower Bible & Tract Society. pp. 309–376.

- ^ John and Morton Edgar (1913). Great Pyramid Passages, Vol. 2 (PDF). Morton Edgar (1924). The Great Pyramid: Its Symbolism, Science and Prophecy (PDF). p. 119.

- ^ Shermer, Michael The Skeptic encyclopedia of pseudoscience, Vol. 2 ABC-CLIO Ltd; illustrated edition (31 Oct 2002) ISBN 978-1-57607-653-8 p.406 [1]

- ^ The Watchtower, November 15 and December 1, 1928. Watchtower, Bible and Tract Society.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology, Lewis Spence, Kessinger Publishing, 2003, pp. 759-760: "...speculations concerning pyramids have centered upon the possible existence of an unknown energy concentrated in pyramidical structures. Pyramid energy was rediscovered in the early 1970s after it was introduced in the popular best-selling Psychic Discoveries behind the Iron Curtain by journalists Sheila Ostrander and Lynn Schroeder. They described their experience with a Czech radio engineer, Karl Drbal, who had taken out a patent on a pyramid razor blade sharpener. The idea was picked up by New Age writer Lyll Wat and then a host of others including Peter Toth, Greg Nielsen, and Pat Flanagan. Through the 1970s, it was a common theme at psychic and New Age gatherings."

- ^ Interventions in applied gerontology, Robert F. Morgan, Kendall/Hunt Pub. Co., 1981, pp.123-125.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology, Lewis Spence, Kessinger Publishing, 2003 (reprint), pp.759-761.

- ^ Atlantis, the Antediluvian World, Ignatius Donnelly, 1882, p. 317.

- ^ The Ancient Egyptians and the origin of Civilization (London/New York, Harper & Brother 1911), p. ix.

- ^ They Built the Pyramids, Joseph Davidovits, Geopolymer Institute, 2008, p. 27.

- ^ Pseudoscience and the Paranormal, Prometheus Books, 2003, Terence Hines, p. 307.

- ^ Technology of the Gods: The Incredible Sciences of the Ancients, David Hatcher Childress, Adventures Unlimited Press (1 Jun 2000).

- ^ Forbidden Science: From Ancient Technologies to Free Energy, J. Douglas Kenyon, Inner Traditions International (21 Mar 2008)

- ^ The Giza Power Plant: Technologies of Ancient Egypt, Christopher Dunn, Bear & Company (31 Oct 1998)

- ^ Alford, Pyramid of Secrets, chapter 4; The Midnight Sun, pp. 352-56, 358-70.

- ^ Alford, News and Views

- ^ Alford, Pyramid of Secrets, chapter 5; The Midnight Sun, pp. 356-58

- ^ Alford, Pyramid of Secrets, pp. 201-4; The Midnight Sun, p. 357.

- ^ Alford, Pyramid of Secrets, chapter 7.

- ^ The Daily Mail, 21st June 2003.

- ^ [2]

- ^ W. M. Flinders Petrie, The Pyramids and Temples of Gizeh (London, 1883), p. 189 [3].

- ^ Great Pyramid Its Divine Message, D. Davidson, H. Aldersmith, Kessinger Publishing, 1992, p. 11.

- ^ Seventy Years in Archaeology, London: Sampsom Low, Marston & Co. p. 35.

- ^ Allen Alter, "The Pyramid and Food Dehydration," New Horizons, Vol. 1 (Summer 1973).

- ^ The incredible Dr. Matrix, Martin Gardner, Scribner, 1976,p. 249

- ^ Pseudoscience and the paranormal, Terence Hines, Prometheus Books, 2003, p. 306.

- ^ Barbara Mertz, Temples, Tombs, and Hieroglyphs: A popular history of ancient Egypt, New York: Dodd, Mead & Co., 1964

- ^ Peter S. Rodman (2007). How Mathematics Happened: The First 50,000 Years. Prometheus Books. p. 175.