Osman I: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

| more = |

| more = |

||

| type = |

| type = |

||

| image = |

|||

| image =_%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D9%8F%D9%84%D8%B7%D8%A7%D9%86_%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%BA%D8%A7%D8%B2%D9%8A_%D8%B9%D9%8F%D8%AB%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%86_%D8%AE%D8%A7%D9%86_%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D9%88%D9%8E%D9%91%D9%84.png |

|||

| alt = |

| alt = |

||

| caption = An imagined portrait of Osman I |

| caption = An imagined portrait of Osman I |

||

Revision as of 13:42, 6 January 2016

| Osman Ghazi | |

|---|---|

| Sultan of the Ottoman Empire Ghazi | |

| Sultan of the Ottoman Empire | |

| Reign | 17 January 1299 – 29 July 1326 |

| Coronation | 3 May 1281 and 4 September 1299 |

| Predecessor | Position established |

| Successor | Orhan |

| Born | 1258 Söğüt, Anatolia |

| Died | 9 August 1326 (age 68) Söğüt, Anatolia, Turkey |

| Consort | Malhun Hatun Rabia Bala Hatun |

| Royal house | House of Osman |

| Father | Ertuğrul |

| Mother | Halime Hatun |

| Religion | Islam |

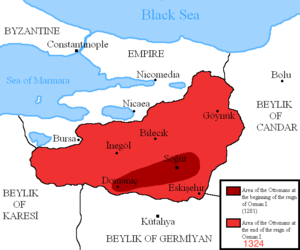

Template:Contains Ottoman Turkish text Osman Ghazi ben Ertuğrul (Ottoman Turkish: عثمان غازى Osman Ghazi; or Osman Bey or Osman Alp); (1258[1]–1326), sometimes transliterated in the past as Othman or Ottoman or Atman (from the contemporary Byzantine Greek version of his name, Άτμαν) and nicknamed "Kara" ( "dark" in Turkish), was the leader of the Ottoman Turks and the founder and namesake of the dynasty that established and ruled the Ottoman Empire. The state, while only a small principality (beylik) during Osman's lifetime, would prevail as a world empire[2] under Osman's dynasty for the next six centuries after his death. It existed until the abolition of the sultanate in 1922, or alternatively the proclamation of the Republic of Turkey in 1923, or the abolition of the caliphate in 1924.

Osman announced the independence of his own small principality from the Seljuk Sultanate of Rum in July 27, 1299, and was acclaimed the Khan of the Kayı tribe.[citation needed] The Ottoman principality was just one of many small Turkish principalities in Anatolia at the time that emerged after the dissolution of the Seljuks, all of which the Ottomans would eventually conquer to reunite Anatolia under Turkish rule. The westward drive of the Mongol invasions had pushed scores of Muslims toward Osman's principality, a power base that Osman was quick to consolidate. As the Byzantine Empire declined, the Ottoman Empire rose to take its place.

Controversy in the origins of his name "Osman"

Since the classical era of the Ottoman Empire, it has been believed that Osman I was named after Uthman ibn Affan, who was the third Rashidun caliph of Islam and one of the companions of the Islamic prophet, Muhammad. However, some historians claim that Osman I's original name was "Atman".[3] This claim is based on the chronicles written by Byzantine historian George Pachymeres, who is contemporary to Osman I. The letter ث in عثمان gives sibilant voiceless alveolar fricative sound and it is translated as "th" to the Latin script. Therefore Osman is translated as "Ottomanus" to Latin and the name of the empire is translated as Ottoman. However, the Greek letter sigma "Σ" is already a sibilant consonant and ع in عثمان should be translated to Greek as omicron or omega instead of alpha in the chronicles.

Another supporting argument to this claim is that neither Osman I's ancestors have Islamic names nor his uncles, brothers, and lieutenants. This may not be true, however, since his grand father is commonly believed to be Suleyman Shah, whose name is Islamic. Being nomads, his ancestors were exposed to Islamic culture very little and they first started to live a sedentary life during the leadership of Ertuğrul in Söğüt. In addition, according to a famous tale, Osman I first saw Quran in the house of Sheikh Edebali, whose daughter Osman I married later. Osman I's eldest son and successor was Orhan, whose name has also origins in old Turkish. The first Islamic name in Osman I's lineage is of his son "Alaeddin". He is possibly named after Alaeddin Keykubad III (died 1303), who was the Seljuk Sultan of Rûm of the era, as a tribute.

Origins of empire

One tradition states that Ertuğrul, Osman I's father, led the Turkic Kayı tribe west from Central Asia into Anatolia, fleeing the Mongol onslaught.[4] His mother was named Halime. He pledged allegiance to Sultan Kayqubad I of the Seljuk principality of Rum, who gave him permission to establish a beylik and expand it if he could, at the expense of the neighboring Byzantine provinces.

This location was auspicious, as the wealthy Byzantine Empire was weakening to his West, while in the east, Muslim forces under the Seljuk Turks were splintered and distracted in the face of relentless Mongol aggression as well as internal bickering.[5] Baghdad had been sacked by Hulagu Khan in 1258, about the time Osman was born. In 1231, Ertuğrul conquered the Nicean (Byzantine) town of Thebasion, which was renamed to Söğüt and became the first capital of his territory—and where Osman was born.[4]

Ottoman historians often dwell on the prophetic significance of his name, which means "bone-breaker", signifying the powerful energy with which he and his followers appeared to show in the following centuries of conquest. The name Osman is the Turkish variation of the name Othman, or Uthman, of Arabic origin.

Osman became chief, or Bey, upon his father’s death (c. 1280). By this time, mercenaries were streaming into his realm from all over the Islamic world to fight against and hopefully plunder the weakening Byzantine empire. In addition, the Turkic population of Osman's emirate were constantly reinforced by a flood of refugees, fleeing from the Mongols. Of these, many were Ghazi warriors, or fighters for Islam, border fighters who believed they were fighting for the expansion or defense of Islam. Under the strong and able leadership of Osman, these warriors quickly proved a formidable force, and the foundations of the Empire were quickly laid.

Osman appears to have followed the strategy of increasing his territories at the expense of the Byzantines while avoiding conflict with his more powerful Turkish neighbors.[4] His first advances were through the passes which lead from the barren areas of northern Phrygia near modern Eskişehir into the more fertile plains of Bithynia; according to Stanford Shaw, these conquests were achieved against the local Byzantine nobles, "some of whom were defeated in battle, others being absorbed peacefully by purchase contracts, marriage contracts, and the like."[6]

These early victories and exploits are favorite subjects of Ottoman writers, especially in love stories of his wooing and winning the fair Mal Hatun. These legends have been romanticized by the poetical pens which recorded them in later years. The Ottoman writers attached great importance to this legendary, dreamlike conception of the founder of their empire.

Osman's Dream

Osman Gazi appreciated the opinions of the famous Ahi Sheikh, Sheik Edebali, and he respected him. Osman often visited Edebali in his home at Eskisehir where a dervish group met.

One night, when Osman was a guest in Edebali’s dergah, he had a dream. As the sun rose, he went to Edebali and told him, “My Sheik, I saw you in my dream. A moon appeared in your breast. It rose, rose and then descended into my breast. From my navel there sprang a tree. It grew and branched out so much, that the shadow of its branches covered the whole world. What does my dream mean?”

After a brief silence, Edebali interpreted:

“Congratulations Osman! God Almighty bestowed sovereignty upon you and your generation. My daughter will be your wife, and the whole world will be under the protection of your children.”

Military victories

According to Shaw, Osman's first real conquests followed the collapse of Seljuk authority when he was able to occupy the fortresses of Eskişehir and Karacahisar. Then he captured the first significant city in his territories, Yenişehir, which became the Ottoman capital.[6]

In 1302, after soundly defeating a Byzantine force near Nicaea, Osman began settling his forces closer to Byzantine controlled areas.[7] Large numbers of Ghazi warriors, Islamic scholars and dervishes began settling in Osman-controlled areas, and migrants composed the bulk of his army. The influx of Ghazi warriors and adventurers of differing backgrounds into these lands spurred subsequent Ottoman rulers to title themselves "Sultan of Ghazis".[7]

Alarmed by Osman's growing influence, the Byzantines gradually fled the Anatolian countryside. Byzantine leadership attempted to contain Ottoman expansion, but their efforts were poorly organized and ineffectual. Meanwhile, Osman spent the remainder of his reign expanding his control in two directions, north along the course of the Sakarya River and southwest towards the Sea of Marmora, achieving his objectives by 1308.[6] That same year his followers participated in conquest of the Byzantine city of Ephesus near the Aegean Sea, thus capturing the last Byzantine city on the coast, although the city became part of the domain of the Emir of Aydin.[7]

Osman's last campaign was against the city of Bursa.[8] Although Osman did not physically participate in the battle, the victory at Bursa proved to be extremely vital for the Ottomans as the city served as a staging ground against the Byzantines in Constantinople, and as a newly adorned capital for Osman's son, Orhan.

Osman the founder of the Ottoman empire- risen from Anatolia and reigned for 600 years, over three continents- Osman Gazi, died of gout, in Bursa in 1326. When he died, he left a horse armor, a pair of high boots, a few sun jacks, a sword, a lance, a tirkes, a few horses, three herds of sheep, salt and spoon containers.

Last testament

In directing his son to continue the administrative policies set forth by Sheik Edebali, Osman stated:

Son! Be careful about the religious issues before all other duties. The religious precepts build a strong state. Do not give religious duties to careless, faithless and sinful men or to dissipated, indifferent or inexperienced people. And also do not leave the state administrations to such people. Because the one with fear of God the Creator, has no fear of the created. One who commits a great sin and continues to sin can not be loyal. Scholars, virtuous men, artists and literary men are the power of the state structure. Treat them with kindness and honour. Build close relationship when you hear about a virtuous man and give wealth and grant him...Put order the political and religious duties. Take lesson from me so I came to these places as a weak leader and I reached to the help of God although I did not deserve. You follow my way and protect Din-i-Muhammadi and the believers and also your followers. Respect the right of God and His servants. Do not hesitate to advise your successors in this way. Depend on God's help in the esteem of justice and fairness, to remove the cruelty, attempts in every duty. Protect your public from enemy's invasion and from the cruelty. Do not behave any person in an unsuitable way with unfairness. Gratify the public and save all of their sake.[9]

The Sword of Osman

The Sword of Osman (Template:Lang-tr)[10] was an important sword of state used during the coronation ceremony of the sultans of the Ottoman Empire.[11] The practice started when Osman was girt with the sword of Islam by his mentor and father-in-law Sheik Edebali.[12] The girding of the sword of Osman was a vital ceremony which took place within two weeks of a sultan's accession to the throne. It was held at the tomb complex at Eyüp, on the Golden Horn waterway in the capital Constantinople. The fact that the emblem by which a sultan was enthroned consisted of a sword was highly symbolic: it showed that the office with which he was invested was first and foremost that of a warrior. The Sword of Osman was girded on to the new sultan by the Sharif of Konya, a Mevlevi dervish, who was summoned to Constantinople for that purpose. Such a privilege was reserved to devout religious leaders from the time Osman had established his residence in Konya in 1299, before the capital was moved to Bursa and later to Constantinople.[13]

Marriages and issue

He married Malhun Hatun in 1280, daughter of Ömer Abdülaziz Bey. He also additionally married Rabia Bala Hatun in 1289, daughter of Sheikh Edebali.

- Alaeddin Pasha, died in 1332, son of Rabia Bala Hatun

- Orhan I, son of Malhun Hatun.

In popular media

Osman is portrayed by Oğuz Oktay in 2012 film Fetih 1453. Osman appears in Mehmed II's (Devrim Evin) dream and tells him that Mehmed is the commander prophesied by Muhammad as Constantinople's conqueror.

See also

- House of Osman

- Osmangazi, Turkey

- TCG Osman Gazi (NL125)

- Ghazan

- Andronicus II Palaeologus

- Seljuk

- Köse Mihal

- The Ottomans: Europe's Muslim Emperors

References

- ^ "The Sultans: Osman Gazi". TheOttomans.org. Retrieved December 13, 2010.

- ^ The Ottoman Empire, 1700-1999, Donald Quataert, page 4, 2005

- ^ Watch Dr. Levent Kayapinar's (Byzantinist) claims on this issue broadcast on Haberturk, a noted Turkish news channel. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xz0GfJizto4

- ^ a b c Stanford Shaw, History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey (Cambridge: University Press, 1976), vol. 1 p. 13

- ^ For an overview of the period following the decisive Battle of Köse Dağ, see Claude Cahen, Pre-Ottoman Turkey: A general survey of the material and spiritual culture and history c. 1071-1330 (New York: Taplinger, 1968), pp. 269—325

- ^ a b c Shaw, Ottoman Empire, p. 14

- ^ a b c Steven Runciman, The Fall of Constantinople 1453 (Cambridge: University Press, 1969) p. 32

- ^ Runciman, The Fall of Constantinople, p. 33

- ^ His testament

- ^ M'Gregor, J. (July 1854). "The Race, Religions, and Government of the Ottoman Empire". The Eclectic Magazine of Foreign Literature, Science, and Art. 32. New York: Leavitt, Trow, & Co.: p. 376. OCLC 6298914. Retrieved 2009-04-25.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - ^ Frederick William Hasluck, [First published 1929], "XLVI. The Girding of the Sultan", in Margaret Hasluck, Christianity and Islam Under the Sultans II, pp. 604–622. ISBN 978-1-4067-5887-0

- ^ Frank R. C. Bagley, The Last Great Muslim Empires (Leiden: Brill, 1969), p. 2 ISBN 978-90-04-02104-4

- ^ "Girding on the Sword of Osman" (PDF). The New York Times: 2. 1876-09-18. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2009-04-19.

External links

![]() Media related to Osman I at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Osman I at Wikimedia Commons