History of New England: Difference between revisions

SpaceStar99 (talk | contribs) Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

Rescuing 2 sources and tagging 1 as dead. #IABot (v1.2.7.1) |

||

| Line 97: | Line 97: | ||

===Education=== |

===Education=== |

||

New England has always had a commanding position in the history of American education. The first American schools in the thirteen colonies opened in the 17th century. [[Boston Latin School]] was founded in 1635 and is both the [[List of the oldest public high schools in the United States|first public school]] and oldest existing school in the United States.<ref>{{cite web |

New England has always had a commanding position in the history of American education. The first American schools in the thirteen colonies opened in the 17th century. [[Boston Latin School]] was founded in 1635 and is both the [[List of the oldest public high schools in the United States|first public school]] and oldest existing school in the United States.<ref>{{cite web |

||

|url=http://www.bls.org/cfml/l3tmpl_history.cfm |

|url=http://www.bls.org/cfml/l3tmpl_history.cfm |

||

|title=History of Boston Latin School—oldest public school in America |

|title=History of Boston Latin School—oldest public school in America |

||

|work=BLS Web Site |

|work=BLS Web Site |

||

|accessdate=2007-06-01 |

|accessdate=2007-06-01 |

||

|archiveurl |

|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20070502223937/http://www.bls.org/cfml/l3tmpl_history.cfm |

||

|archivedate=2007-05-02 |

|||

|deadurl=yes |

|||

|df= |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

Cremin (1970) stresses that colonists tried at first to educate by the traditional English methods of family, church, community, and apprenticeship, with schools later becoming the key agent in "socialization". At first, the rudiments of literacy and arithmetic were taught inside the family, assuming the parents had those skills. Literacy rates seem to have been much higher in New England, and much lower in the South. By the mid-19th century, the role of the schools had expanded to such an extent that many of the educational tasks traditionally handled by parents became the responsibility of the schools.<ref>Lawrence Creminm ''American Education: The Colonial Experience, 1607-1783'' (Harper & Row, 1970)</ref><ref>Maris A. Vinovskis, "Family and Schooling in Colonial and Nineteenth-Century America," ''Journal of Family History," Jan 1987, Vol. 12 Issue 1-3, pp 19-37</ref> |

Cremin (1970) stresses that colonists tried at first to educate by the traditional English methods of family, church, community, and apprenticeship, with schools later becoming the key agent in "socialization". At first, the rudiments of literacy and arithmetic were taught inside the family, assuming the parents had those skills. Literacy rates seem to have been much higher in New England, and much lower in the South. By the mid-19th century, the role of the schools had expanded to such an extent that many of the educational tasks traditionally handled by parents became the responsibility of the schools.<ref>Lawrence Creminm ''American Education: The Colonial Experience, 1607-1783'' (Harper & Row, 1970)</ref><ref>Maris A. Vinovskis, "Family and Schooling in Colonial and Nineteenth-Century America," ''Journal of Family History," Jan 1987, Vol. 12 Issue 1-3, pp 19-37</ref> |

||

[[File:Boston Latin School original.jpg|thumb|right|First [[Boston Latin School]] House]] |

[[File:Boston Latin School original.jpg|thumb|right|First [[Boston Latin School]] House]] |

||

All the New England colonies required towns to set up schools, and many did so. In 1642 the [[Massachusetts Bay Colony]] made "proper" education compulsory; other New England colonies followed. Similar statutes were adopted in other colonies in the 1640s and 1650s. The schools were all male, with few facilities for girls.<ref>{{Cite web |

All the New England colonies required towns to set up schools, and many did so. In 1642 the [[Massachusetts Bay Colony]] made "proper" education compulsory; other New England colonies followed. Similar statutes were adopted in other colonies in the 1640s and 1650s. The schools were all male, with few facilities for girls.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://faculty.mdc.edu/jmcnair/Joe28pages/Schooling,%20Education,%20and%20Literacy%20in%20Colonial%20America.htm |title=Schooling, Education, and Literacy, In Colonial America |accessdate= |author= |authorlink= |coauthors= |date=2010-04-01 |year= |month= |work= |publisher=faculty.mdc.edu |pages= |language= |quote= |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20110110043822/http://faculty.mdc.edu:80/jmcnair/Joe28pages/Schooling,%20Education,%20and%20Literacy%20in%20Colonial%20America.htm |archivedate=2011-01-10 |df= }}</ref> In the 18th century, "common schools", appeared; students of all ages were under the control of one teacher in one room. Although they were publicly supplied at the local (town) level, they were not free, and instead were supported by tuition or "rate bills". |

||

The larger towns in New England opened grammar schools, the forerunner of the modern high school.<ref>Small, Walter H. “The New England Grammar School, 1635-1700.” ''School Review'' 7 (September 1902): 513-31</ref> The most famous was the [[Boston Latin School]], which is still in operation as a public high school. [[Hopkins School]] in New Haven, Connecticut, was another. By the 1780s, most had been replaced by private academies. By the early 19th century New England operated a network of [[List of New England prep schools|elite private high schools]], now called "prep schools", typified by [[Phillips Academy|Phillips Andover Academy]] (1778), [[Phillips Exeter Academy]] (1781), and [[Deerfield Academy]] (1797). They became coeducational in the 1970s, and remain highly prestigious in the 21st century.<ref>James McLachlan, ''American boarding schools: A historical study'' (1970)</ref><ref>Arthur Powell, ''Lessons from Privilege: The American Prep School Tradition'' (Harvard UP, 1998)</ref> |

The larger towns in New England opened grammar schools, the forerunner of the modern high school.<ref>Small, Walter H. “The New England Grammar School, 1635-1700.” ''School Review'' 7 (September 1902): 513-31</ref> The most famous was the [[Boston Latin School]], which is still in operation as a public high school. [[Hopkins School]] in New Haven, Connecticut, was another. By the 1780s, most had been replaced by private academies. By the early 19th century New England operated a network of [[List of New England prep schools|elite private high schools]], now called "prep schools", typified by [[Phillips Academy|Phillips Andover Academy]] (1778), [[Phillips Exeter Academy]] (1781), and [[Deerfield Academy]] (1797). They became coeducational in the 1970s, and remain highly prestigious in the 21st century.<ref>James McLachlan, ''American boarding schools: A historical study'' (1970)</ref><ref>Arthur Powell, ''Lessons from Privilege: The American Prep School Tradition'' (Harvard UP, 1998)</ref> |

||

| Line 128: | Line 132: | ||

[[File:Massachusetts Revolutionary War loan certificate September 1777.jpg|thumb|right|260px|Certificate of government of Massachusetts Bay acknowledging loan of £20 to state treasury 1777]] Parliament passed the [[Intolerable Acts]] in 1774 that brought stiff punishment. It closed the port of Boston, the economic lifeblood of the Commonwealth, and ended self-government, putting the people under military rule. The patriots set up a shadow government, which the British Army attacked on April 18, 1775 at [[Concord, Massachusetts|Concord]]. On the 19th, in the [[Battles of Lexington and Concord]], where the famous "[[shot heard 'round the world]]" was fired, British troops were forced back into the city by the local militias, under the control of the shadow government. The British army controlled only the city of Boston, and it was quickly [[Siege of Boston|brought under siege]]. The Continental Congress took control of the war, sending General [[George Washington]] to take charge. He forced the British to evacuate in March 1776. After that, the main warfare moved south, but the British made repeated raids along the coast, and seized part of Rhode Island and Maine for a while. On the whole, the patriots controlled 99 percent of the New England population.<ref>David Hackett Fischer, ''Paul Revere's Ride'' (1994)</ref> |

[[File:Massachusetts Revolutionary War loan certificate September 1777.jpg|thumb|right|260px|Certificate of government of Massachusetts Bay acknowledging loan of £20 to state treasury 1777]] Parliament passed the [[Intolerable Acts]] in 1774 that brought stiff punishment. It closed the port of Boston, the economic lifeblood of the Commonwealth, and ended self-government, putting the people under military rule. The patriots set up a shadow government, which the British Army attacked on April 18, 1775 at [[Concord, Massachusetts|Concord]]. On the 19th, in the [[Battles of Lexington and Concord]], where the famous "[[shot heard 'round the world]]" was fired, British troops were forced back into the city by the local militias, under the control of the shadow government. The British army controlled only the city of Boston, and it was quickly [[Siege of Boston|brought under siege]]. The Continental Congress took control of the war, sending General [[George Washington]] to take charge. He forced the British to evacuate in March 1776. After that, the main warfare moved south, but the British made repeated raids along the coast, and seized part of Rhode Island and Maine for a while. On the whole, the patriots controlled 99 percent of the New England population.<ref>David Hackett Fischer, ''Paul Revere's Ride'' (1994)</ref> |

||

[[New England's Dark Day]] struck on May 19, 1780. While residents were apprehensive at the time, for lack of a clear cause for the darkness requiring candlelight in the middle of the day, it appears that forest fires, a fog, and cloud cover, all contributed.<ref name="Ross">[http://www.americanheritage.com/articles/magazine/ah/2008/5/2008_5_8_dept.shtml John Ross] "Dark Day of 1780," ''American Heritage'', Fall 2008.</ref> |

[[New England's Dark Day]] struck on May 19, 1780. While residents were apprehensive at the time, for lack of a clear cause for the darkness requiring candlelight in the middle of the day, it appears that forest fires, a fog, and cloud cover, all contributed.<ref name="Ross">[http://www.americanheritage.com/articles/magazine/ah/2008/5/2008_5_8_dept.shtml John Ross]{{dead link|date=December 2016 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }} "Dark Day of 1780," ''American Heritage'', Fall 2008.</ref> |

||

===Early national period=== |

===Early national period=== |

||

Revision as of 11:32, 1 December 2016

This article presents the History of New England, the oldest clearly defined region of the United States. While New England was originally inhabited by Indigenous peoples, English Pilgrims and especially Puritans, fleeing religious persecution in England, arrived in the 1620-1660 era. They dominated the region; their religion was later called Congregationalism. They and their descendants are called Yankees. Farming, fishing and lumbering prospered, as did whaling, sea trading, and merchandising. The region was the scene of the first Industrial Revolution in the United States, with many textile mills and machine shops operating by 1830.

New England (and Virginia) led the way to the American Revolution. The region became a stronghold of the conservative Federalist Party and opposed the War of 1812 with Great Britain. By the 1840s it was the center of the American anti-slavery movement, and was the leading force in American literature and higher education. The English Catholics came to America in the 1600s because they wanted to escape religious persecution.

Indigenous people

New England has long been inhabited by Algonquian-speaking native peoples, including the Abenaki, the Penobscot, the Pequot, the Wampanoag, and many others. During the 15th and 16th centuries, Europeans such as Giovanni da Verrazzano, Jacques Cartier and John Cabot (known as Giovanni Caboto before being based in England) charted the New England coast. They referred to the region as Norumbega, named for a fabulous native city that was supposed to exist there.

The earliest known inhabitants of New England were Native Americans who spoke a variety of the Eastern Algonquian languages.[1] Some of the more prominent tribes include the Abenaki, the Penobscot, the Pequot, the Mohegans, the Pocumtuck, and the Wampanoag.[1] Prior to the arrival of Europeans, the Western Abenakis inhabited New Hampshire and Vermont, as well as parts of Quebec and western Maine.[2] Their principal town was Norridgewock, in present-day Maine.[3] The Penobscot were settled along the Penobscot River in Maine. The Wampanoag occupied southeastern Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and the islands of Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket; the Pocumtucks, Western Massachusetts. The Connecticut region was inhabited by the Mohegan and Pequot tribes prior to European colonization. The Connecticut River Valley, which includes parts of Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Connecticut, linked different indigenous communities in cultural, linguistic, and political ways.[1]

According to archaeological evidence, the indigenous people of the warmer parts of Southern New England had started agricultural endeavors over a thousand years ago. They grew corn, tobacco, kidney beans, squash, and Jerusalem artichoke. Trade with the Algonquian peoples of Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine, where the growing season was shorter, likely provided for a robust economy.[1]

As early as 1600, French, Dutch, and English traders, exploring the New World, began to trade metal, glass, and cloth for local beaver pelts.[1][4] The traders and sailors brought previously unknown European diseases, especially smallpox, measles, malaria, and yellow fever, which quickly spread along trade routes and killed a majority of the Indians in the region by the 1630s.[5]

Colonial era

Early European settlement (1607–1620)

On 1606-04-10, King James I of England issued two charters, one each for the Virginia Companies, of London and Plymouth, respectively.[6][7] Due to a duplication of territory (between Chesapeake Bay and Long Island Sound), the two companies were required to maintain a separation of 100 miles (160 km), even where the two charters overlapped.[8][9][10] The London Company was authorized to make settlements from North Carolina to New York (31 to 41 degrees North Latitude), provided there was no conflict with the Plymouth Company’s charter. The purpose of both was to claim land for England and trade.

- Under the charters, the territory allocated was defined as follows:

- Virginia Company of London: All land, including islands within 100 miles (160 km) from the coast and implying a westward limit of 100 miles (160 km), between 34 Degrees (Cape Fear, North Carolina) and 41 Degrees (Long Island Sound, New York) north latitude.[6][7]

- Virginia Company of Plymouth: All land, including islands within 100 miles (160 km) from the coast and implying a westward limit of 100 miles (160 km), between 38 Degrees (Chesapeake Bay, Virginia) and 45 Degrees (Border between Canada and Maine) north latitude.[6][7] Its charter included land extending as far as present-day northern Maine.

These were privately funded proprietary ventures, and the purpose of each was to claim land for England, trade, and return a profit. The Virginia Company of London successfully established the Jamestown Colony in Virginia in 1607. The region was named "New England" by Captain John Smith, who explored its shores in 1614, in his account of two voyages there, published as A Description of New England.

Plymouth (1620–1643)

The name "New England" was officially sanctioned on November 3, 1620, when the charter of the Virginia Company of Plymouth was replaced by a royal charter for the Plymouth Council for New England, a joint stock company established to colonize and govern the region. In December 1620, a permanent settlement known as the Plymouth Colony was established at present-day Plymouth, Massachusetts by the Pilgrims, English religious separatists arriving via Holland. They arrived aboard a ship named the Mayflower and held a feast of gratitude which became part of the American tradition of Thanksgiving. Plymouth, with a small population and limited size, was absorbed by Massachusetts in 1691.

In 1638, a "violent" earthquake was felt throughout New England, centered in the St. Lawrence Valley. This was the first recorded seismic event noted in New England.[11]

Even during the early stages of English colonization, relations with the indigenous peoples of New England began to sour.[1] Preliminary trade with Europeans had already significantly reduced and weakened native populations via disease and epidemic. The fur supply was soon exhausted, forcing hunters to travel farther into the territories of neighboring tribes, such as the Mohawk and the Haudenosaunee (known to European settlers as the Iroquois) of Eastern New York.[1] As demand for local goods, like beaver pelts, by English companies rose, so did tensions between existing indigenous communities. Permanent English settlement, through which colonists seized or claimed land and began to apply Puritan laws to native peoples, exacerbated the situation.[1]

Massachusetts Puritans

The Massachusetts Bay Colony, which would come to dominate the area, was established in 1628 with its major city of Boston established in 1630.

The Puritans, a much larger group than the Pilgrims, established the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1629 with 400 settlers. They sought to reform the Church of England by creating a new, pure church in the New World. By 1640, 20,000 had arrived; many died soon after arrival, but the others found a healthy climate and an ample food supply. See Migration to New England (1620–1640).

The Puritans created a deeply religious, socially tight-knit, and politically innovative culture that still influences the modern United States.[12] They hoped this new land would serve as a "redeemer nation". They fled England and in America attempted to create a "nation of saints" or a "City upon a Hill": an intensely religious, thoroughly righteous community designed to be an example for all of Europe.

By 1723, Puritan cultural and religious influence had declined substantially in Boston. One of Ben Franklin's first printed works decried frivolity among Harvard students.[13]

Other New England colonies

Roger Williams, who preached religious toleration, separation of Church and State, and a complete break with the Church of England, was banished from Massachusetts for his theological heresies and led a group south to found Providence in 1636. It merged with other settlements to form Rhode Island Colony. This region became a haven for Baptists, Quakers, and other refugees from the Puritan community, such as Anne Hutchinson who had been banished during the Antinomian Controversy.[14]

On March 3, 1636, the Connecticut Colony was granted a charter and established its own government. The nearby New Haven Colony was absorbed by Connecticut.

Vermont was then unsettled, and the territories of New Hampshire and Maine were then governed by Massachusetts.

Early colonial wars

Relationships between colonists and Native Americans alternated between peace and armed skirmishes, the bloodiest of which was the Pequot War in 1636, which resulted in the Mystic massacre. Six years later, the colonies of Massachusetts Bay, Plymouth, New Haven, and Connecticut joined together in a loose compact called the New England Confederation (officially "The United Colonies of New England"). The confederation was designed largely to coordinate mutual defense, but was never effective and soon collapsed.[citation needed]

In 1675, King Philip's War pitted the colonists and their Native American allies against a widespread Native American uprising, resulting in massacres and killings on both sides. The colonists won in the south decisively, however, they were forced to sign peace treaties in the North in present-day New Hampshire and Maine.[citation needed]

The Dominion of New England (1686–1689)

In 1686, King James II, concerned about the increasingly independent ways of the colonies, in particular their self-governing Charters, open flouting of the Navigation Acts and their increasing military power decreed the Dominion of New England, an administrative union comprising all the New England colonies. Two years later, the provinces of New York (New Amsterdam) and the New Jersey, which had been confiscated by force from the Dutch, were added. The union, imposed from the outside, and removing nearly all their popularly elected leaders, was highly unpopular among the colonists. In 1687, when the Connecticut Colony refused to follow a decision of the dominion governor Edmund Andros to turn over their charter, he sent an armed contingent to seize the colony's charter. According to popular legend, the colonists hid the charter inside the Charter Oak tree. Andros' efforts to loot the colonies, replace their leaders and to unify the colonial defenses under his control met little success and the dominion ceased after only three years. After the very popular removal of King James II in the Glorious Revolution of 1689, Andros was arrested and sent back to England by the colonists during the 1689 Boston revolt.[15]

Later colonial wars

From 1688 to 1763, there were six colonial wars that took place primarily between Great Britain and New France (see the French and Indian Wars as well as Father Rale's War and Father Le Loutre's War). Throughout these wars, New England was allied with the Iroquois Confederacy and New France was allied with the Wabanaki Confederacy. After the New England Conquest of Acadia in 1710, mainland Nova Scotia was laid claim to by the British, but both present-day New Brunswick and virtually all of present-day Maine remained contested territory between Great Britain and New France. During the final French and Indian War, New England deported the Acadians from Nova Scotia and replaced them with New England Planters. After the British won the war in 1763, the Connecticut River Valley was opened up for settlement into western New Hampshire and what is today Vermont.

Government of the colonies

After the Glorious Revolution in 1689 the charters of most of the colonies were significantly modified with the appointment of Royal Governors to nearly each colony. An uneasy tension existed between the Royal Governors, their officers and the elected governing bodies in the colonies. The governors wanted essentially unlimited arbitrary powers and the different layers of locally elected officials resisted as best they could. In most cases the local town governments continued operating as self-governing bodies as they had before the Royal Governors showed up and to the extent possible ignored the Royal Governors. This tension eventually led to the American Revolution when the states formed their own governments. The colonies were not formally united again until 1776 as newly formed states, when they declared themselves independent states in a larger (but not yet federalist) union called the United States.

Regional character

Aside from the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, or "New Scotland", New England is the only North American region to inherit the name of a kingdom in the British Isles. New England has largely preserved its regional character, especially in its historic sites. Its name is a reminder of the past, as many of the original English-Americans have migrated further west.

Population and demographics

The New England States were initially colonized by about 30,000 settlers between 1620 and 1640, a period now referred to as "The Great Migration". There was little additional immigration until the Irish influx of the 1840s and '50s in the wake of the potato famine.

The regional economy grew rapidly in the 17th century, thanks to heavy immigration, high birth rates, low death rates, and an abundance of inexpensive farmland.[16] The population grew from 3000 in 1630 to 14,000 in 1640, 33,000 in 1660, 68,000 in 1680, and 91,000 in 1700. Between 1630 and 1643, about 20,000 Puritans arrived, settling mostly near Boston; after 1643 fewer than fifty immigrants a year arrived. The average size of a completed family 1660-1700 was 7.1 children; the birth rate was 49 babies per year per 1000 people, and the death rate was about 22 deaths per year per thousand people. About 27 percent of the population comprised men between 16 and 60 years old.[17]

The almost one million inhabitants in 1770, just before the Revolution were nearly all descended from the original settlers, whose 3 percent annual natural growth rate caused a doubling of population every 25 years. Their beliefs and ancestry were nearly all shared and made them into what was probably the largest more-or-less homogeneous group of settlers in America. Their high birth rate continued for at least a century more, making the descendants of these New Englanders well represented in nearly all states today. In the 18th century and the early 19th century, New England was still considered to be a very distinct region of the country, as it is today. During the War of 1812, there was a limited amount of talk of secession from the Union, as New England merchants, just getting back on their feet, opposed the war with their greatest trading partner — Great Britain.

After the American Revolutionary War, Connecticut and Massachusetts ceded tracts of land to the federal government that they had claimed in the Northwest Territory and the Western Reserve exceeding their modern-day areas.

Economics

The New England colonies were settled largely by farmers, who became relatively self-sufficient. Later, aided by the Puritan work ethic and the arrival of wealthier English colonists, New England's economy began to focus on crafts and trade, in contrast to the Southern colonies, whose agrarian-based economy focused more heavily on foreign and domestic trade.[18]

Economically, Puritan New England fulfilled the expectations of its founders. Unlike the cash crop-oriented plantations of the Chesapeake region, the Puritan economy was based on the efforts of self-supporting farmsteads who traded only for goods they could not produce themselves.[19] There was a generally higher economic standing and standard of living in New England than in the Chesapeake. Along with agriculture, fishing, and logging, New England became an important mercantile and shipbuilding center, serving as the hub for trading between the southern colonies and Europe.[20]

The region's economy grew steadily over the entire colonial era, despite the lack of a staple crop that could be exported. All the provinces, and many towns as well, tried to foster economic growth by subsidizing projects that improved the infrastructure, such as roads, bridges, inns and ferries. They gave bounties and subsidies or monopolies to sawmills, grist mills, iron mills, fulling mills (which treated cloth), salt works and glassworks. Most important, colonial legislatures set up a legal system that was conducive to business enterprise by resolving disputes, enforcing contracts, and protecting property rights. Hard work and entrepreneurship characterized the region, as the Puritans and Yankees endorsed the "Protestant Ethic", which enjoined men to work hard as part of their divine calling.[21]

Focused on shipping as well as production, New England conducted a robust trade within the English domain in the mid-18th century. They exported to the Caribbean: pickled beef and pork, onions and potatoes from the Connecticut valley, codfish to feed their slaves, northern pine and oak staves from which the planters constructed containers to ship their sugar and molasses, Narragansett Pacers from Rhode Island, and "plugs" to run sugar mills.[22]

Benjamin Franklin in 1772, after examining the wretched hovels in Scotland surrounding the opulent mansions of the land owners, said that in New England every man is a property owner, "has a Vote in public Affairs, lives in a tidy, warm House, has plenty of good Food and Fuel, with whole clothes from Head to Foot, the Manufacture perhaps of his own family."[23]

The benefits of growth were widely distributed, with even farm laborers better off at the end of the colonial period. The growing population led to shortages of good farm land on which young families could establish themselves; one result was to delay marriage, and another was to move to new lands further west. In the towns and cities, there was strong entrepreneurship, and a steady increase in the specialization of labor. Wages for men went up steadily before 1775; new occupations were opening for women, including weaving, teaching, and tailoring. The region bordered New France, and in the numerous wars the British poured money in to purchase supplies, build roads and pay colonial soldiers. The coastal ports began to specialize in fishing, international trade and shipbuilding—and after 1780 in whaling. Combined with a growing urban markets for farm products, these factors allowed the economy to flourish despite the lack of technological innovation.[24]

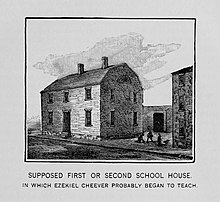

Education

New England has always had a commanding position in the history of American education. The first American schools in the thirteen colonies opened in the 17th century. Boston Latin School was founded in 1635 and is both the first public school and oldest existing school in the United States.[25] Cremin (1970) stresses that colonists tried at first to educate by the traditional English methods of family, church, community, and apprenticeship, with schools later becoming the key agent in "socialization". At first, the rudiments of literacy and arithmetic were taught inside the family, assuming the parents had those skills. Literacy rates seem to have been much higher in New England, and much lower in the South. By the mid-19th century, the role of the schools had expanded to such an extent that many of the educational tasks traditionally handled by parents became the responsibility of the schools.[26][27]

All the New England colonies required towns to set up schools, and many did so. In 1642 the Massachusetts Bay Colony made "proper" education compulsory; other New England colonies followed. Similar statutes were adopted in other colonies in the 1640s and 1650s. The schools were all male, with few facilities for girls.[28] In the 18th century, "common schools", appeared; students of all ages were under the control of one teacher in one room. Although they were publicly supplied at the local (town) level, they were not free, and instead were supported by tuition or "rate bills".

The larger towns in New England opened grammar schools, the forerunner of the modern high school.[29] The most famous was the Boston Latin School, which is still in operation as a public high school. Hopkins School in New Haven, Connecticut, was another. By the 1780s, most had been replaced by private academies. By the early 19th century New England operated a network of elite private high schools, now called "prep schools", typified by Phillips Andover Academy (1778), Phillips Exeter Academy (1781), and Deerfield Academy (1797). They became coeducational in the 1970s, and remain highly prestigious in the 21st century.[30][31]

Colleges

Harvard College was founded by the colonial legislature in 1636, and named after an early benefactor. Most of the funding came from the colony, but the college early began to collect endowment. Harvard at first focused on training young men for the ministry, and one general support from the Puritan colonies. Yale College was founded in 1701, and in 1716 was relocated to New Haven, Connecticut. The conservative Puritan ministers of Connecticut had grown dissatisfied with the more liberal theology of Harvard, and wanted their own school to train orthodox ministers. Dartmouth College, chartered in 1769, grew out of school for Indians, and was moved to its present site in Hanover, New Hampshire, in 1770. Brown University was founded by Baptists in 1764 as the College in the English Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations.[32]

Girls

Tax-supported schooling for girls began as early as 1767 in New England. It was optional and some towns proved reluctant. Northampton, Massachusetts, for example, was a late adopter because it had many rich families who dominated the political and social structures and they did not want to pay taxes to aid poor families. Northampton assessed taxes on all households, rather than only on those with children, and used the funds to support a grammar school to prepare boys for college. Not until after 1800 did Northampton educate girls with public money. In contrast, the town of Sutton, Massachusetts, was diverse in terms of social leadership and religion at an early point in its history. Sutton paid for its schools by means of taxes on households with children only, thereby creating an active constituency in favor of universal education for both boys and girls.[33]

Historians point out that reading and writing were different skills in the colonial era. School taught both, but in places without schools reading was mainly taught to boys and also a few privileged girls. Men handled worldly affairs and needed to read and write. Girls only needed to read (especially religious materials). This educational disparity between reading and writing explains why the colonial women often could read, but could not write and could not sign their names—they used an "X".[34]

1770-1900

American Revolution

New England, especially Boston, was the center of revolutionary activity in the decade before 1775, with Massachusetts politicians Samuel Adams, John Adams, and John Hancock as leaders. New Englanders, like all Americans, were very proud of their political freedoms and local democracy, which they felt was increasingly threatened by the British imperial government. The main grievance was taxation, which colonists argued could only be imposed by their own legislatures, and not by the Parliament in London. Their political cry was, "No taxation without representation!" On December 16, 1773, when a ship was planning to land taxed tea in Boston, local activists calling themselves the Sons of Liberty, disguised themselves as Indians, raided the ship, and dumped all the tea into the harbor. This Boston Tea Party outraged British officials, and the King and Parliament decided to punish Massachusetts.

Parliament passed the Intolerable Acts in 1774 that brought stiff punishment. It closed the port of Boston, the economic lifeblood of the Commonwealth, and ended self-government, putting the people under military rule. The patriots set up a shadow government, which the British Army attacked on April 18, 1775 at Concord. On the 19th, in the Battles of Lexington and Concord, where the famous "shot heard 'round the world" was fired, British troops were forced back into the city by the local militias, under the control of the shadow government. The British army controlled only the city of Boston, and it was quickly brought under siege. The Continental Congress took control of the war, sending General George Washington to take charge. He forced the British to evacuate in March 1776. After that, the main warfare moved south, but the British made repeated raids along the coast, and seized part of Rhode Island and Maine for a while. On the whole, the patriots controlled 99 percent of the New England population.[35]

New England's Dark Day struck on May 19, 1780. While residents were apprehensive at the time, for lack of a clear cause for the darkness requiring candlelight in the middle of the day, it appears that forest fires, a fog, and cloud cover, all contributed.[36]

Early national period

Anti-slavery

After independence, New England ceased to be a meaningful political unit, but remained a defined historical and cultural region consisting of its now-sovereign constituent states. By 1784, all of the states in the region had introduced the gradual abolition of slavery, with Vermont and Massachusetts introducing total abolition in 1777 and 1783, respectively.[37] During the War of 1812, there was a limited amount of talk of secession from the Union, as New England merchants, just getting back on their feet, opposed the war with their greatest trading partner—Britain.[38] Delegates from all over New England met in Hartford in the winter of 1814-15. The gathering was called the Hartford Convention. The twenty-seven delegates met to discuss changes to the US Constitution that would protect the region from similar legislation and attempt to keep political power in the region.

In 1820, as part of the Missouri Compromise, the territory of Maine, formerly a part of Massachusetts, was admitted to the Union as a state. Today, New England is always defined as coextensive with the six states of Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont.[39]

For the remainder of the antebellum period, New England remained distinct. In terms of politics, it often went against the grain of the rest of the country. Massachusetts and Connecticut were among the last refuges of the Federalist Party, and, when the Second Party System began in the 1830s, New England became the strongest bastion of the new Whig Party. The Whigs were usually dominant throughout New England, except in the more Democratic Maine and New Hampshire. Leading statesmen — including Daniel Webster — hailed from the region.

New England and areas settled from New England, like Upstate New York, Ohio's Western Reserve and the upper midwestern states of Michigan and Wisconsin, proved to be the center of the strongest abolitionist sentiment in the country. Abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips were New Englanders, and the region was home to anti-slavery politicians like John Quincy Adams, Charles Sumner, and John P. Hale. When the anti-slavery Republican Party was formed in the 1850s, all of New England, including areas that had previously been strongholds for both the Whig and the Democratic Parties, became strongly Republican, as it would remain until the early 20th century, when immigration turned the formerly solidly Republican states of Lower New England towards the Democrats.

Urbanization

New England was distinct becoming the most urbanized part of the country (the 1860 Census showed that 32 of the 100 largest cities in the country were in New England), as well as the most educated. Notable literary and intellectual figures produced by the United States in the Antebellum period were New Englanders, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, John Greenleaf Whittier, George Bancroft, William H. Prescott, and others.[40]

Industrialization

New England was an early center of the industrial revolution. In Beverly, Massachusetts the first cotton mill in America was founded in 1787, the Beverly Cotton Manufactory.[41] The Manufactory was also considered the largest cotton mill of its time. Technological developments and achievements from the Manufactory led to the development of other, more advanced cotton mills later, including Slater Mill in Pawtucket, Rhode Island. Several textile mills were already underway during the time. Towns like Lawrence, Massachusetts, Lowell, Massachusetts, Woonsocket, Rhode Island, and Lewiston, Maine became famed as centers of the textile industry following models from Slater Mill and the Beverly Cotton Manufactory. The textile manufacturing in New England was growing rapidly, which caused a shortage of workers. Recruiters were hired by mill agents to bring young women and children from the countryside to work in the factories. Between 1830 and 1860, thousands of farm girls came from their rural homes in New England to work in the mills. Farmers’ daughters left their homes to aid their families financially, save for marriage, and widen their horizons. They also left their homes due to population pressures to look for opportunities in expanding New England cities. Stagecoach and railroad services made it easier for the rapid flow of workers to travel from the country to the city. The majority of female workers came from rural farming towns in northern New England. As the textile industry grew, immigration grew as well. As the number of Irish workers in the mills increased, the number of young women working in the mills decreased. At first the mills employed young Yankee farm women; they then used Irish and French immigrants.[42]

Agriculture

As New England’s urban, industrial economy transformed from the beginning of the early national period (~1790) to the middle of the nineteenth century, so too did its agricultural economy. At the beginning of this period, when the United States was just emerging from its colonial past, the agricultural landscape of New England was defined overwhelmingly by subsistence farming.[43] The primary crops produced were wheat, barley, rye, oats, turnips, parsnips, carrots, onions, cucumbers, beets, corn, beans, pumpkins, squashes, and melons.[44] Because there was not a sufficiently large New England-based home market for agricultural products due to the absence of a large nonagricultural population, New England farmers by and large had no incentive to commercialize their farms.[43] Thus, as farmers could not find very many markets nearby to sell to, they generally could not earn enough income with which to buy many new products for themselves. This not only meant that farmers would largely produce their own food, but also that they tended to produce their own furniture, clothing, and soap, among other household items.[43] Hence, according to historian Percy Bidwell, at the onset of the early national period, much of the New England agricultural economy was characterized by a “lack of exchange; lack of differentiation of employments or division of labor; the absence of progress in agricultural methods; a relatively low standard of living; emigration and social stagnation.”[43] As Bidwell writes, the farming in New England at this time was “practically uniform” with many farmers distributing their land “in about the same proportions into pasturage, woodland, and tillage, and raised about the same crops and kept about the same kind and quantity of stock” as other farmers.[45] This situation would, however, be radically different by 1850, by which time a highly specialized agricultural economy producing a host of new and differentiated products had emerged. There were two factors that were primarily responsible for the revolutionary changes in the agricultural economy of New England during the period from 1790 to 1850: (1) The rise of the manufacturing industry in New England (industrialization), and (2) agricultural competition from the western states.[46]

During this period, the industrial jobs created in New England’s towns and cities affected the agricultural economy profoundly by generating a rapidly growing nonagricultural, urbanizing population. The farmers finally had a nearby market to which they could sell their crops, and thus an opportunity to obtain incomes beyond what they produced for subsistence.[47] This new market enabled farmers to make their farms more productive.[47] There was a resultant move away from subsistence farming toward the production of specialized crops. The demands of the consumers of the crops, whether factories or individuals, now determined the kinds of crops that each farm cultivated. Potash, pearlash, charcoal, and fuel wood were among the agricultural products that were produced in greater quantities during this time.[48] The increasing specialization of agriculture even led to production of tobacco, a predominantly southern crop, from central Connecticut to northern Massachusetts, where natural conditions were amenable to its growth.[49] Many agricultural societies were formed to promote improved farming,[50] and they did so by dispensing information on new technological innovations such as the cast-iron plough, which rapidly replaced the wooden plough by the 1830s, as well as mowing machines and horse-rakes.[51] Another important result of the manufacturing boom in New England was the new abundance of cheap products that formerly had to be produced on the farm. For example, myriad new mills produced inexpensive textiles, and it now made more economic sense for many farm women to purchase these textiles rather than spin and weave them at home. Women consequently found new employment elsewhere, typically at the mills, many of which had a shortage of workers, and they began to earn cash incomes.[52]

The agricultural competition that emerged from the western states due to improvements in transportation (e.g., railroads and steamboats) also helped shape agriculture in New England. Competition from the western states was principally responsible for the decline in local pork production and cattle-fattening, as well as that in wheat production.[52] New England farmers now aimed to produce goods with which western farmers could not compete. Consequently, many New England farms came to specialize in “highly perishable and bulky produce,” according to historian Darwin Kelsey. These crops included milk, butter, potatoes, and broomcorn.[53] Thus, both the rise of manufacturing during the industrial revolution and the rise of western competition generated substantial agricultural specialization.

The largely differentiated agricultural landscape of the New England of 1850[54] was distinct from the subsistence-dominated landscape that existed 40–60 years prior. This period of time, therefore, was not only noteworthy in terms of New England’s industrial revolution, but also in terms of New England’s agricultural revolution. MIT economic historian Peter Temin has pointed out that the “transformation of the New England economy in the middle fifty years of the nineteenth century was comparable in scope and intensity to the Asian ‘miracles’ of Korea and Taiwan in the half-century since World War II.”[55] The extensive changes in agriculture that occurred were an important aspect of this economic process.

The CSS Tallahassee disrupted shipping to New England in August 1864.[56]

There have been waves of immigration from Ireland, Quebec, Italy, Portugal, Asia, Latin America, Africa, other parts of the United States, and elsewhere.

New England and political thought

During the colonial period and the early years of the American republic, New England leaders like James Otis, John Adams, and Samuel Adams joined Patriots in Philadelphia and Virginia to define Republicanism, and lead the colonies to a war for independence against Great Britain. New England was a Federalist stronghold, and strongly opposed the War of 1812. After 1830 it became a Whig party, stronghold as exemplified by Daniel Webster in the Second Party System. At the time of the American Civil War, New England, the mid-Atlantic, and the Midwest, which had long since abolished slavery, united against the Confederate States of America, ending the practice in the United States. Henry David Thoreau, iconic New England writer and philosopher, made the case for civil disobedience and individualism.

French Canadians

French-Canadians, living a highly traditional life in rural Canada, were attracted to New England textile mills after 1850.[57][58] Of the 1.5 million people in French-speaking Canada, about 600,000 migrated to the U.S., especially to New England.[59]

The first migrants went to nearby areas of northern Vermont and New Hampshire. However, as the textile factories increased their hiring, the principle destination beginning in the late 1870s until the end of the last immigration wave in the early 1900s, was southern Massachusetts.[60] Though many of these later immigrants were looking for short term employment that would allow them to make enough money to go back home and settle comfortably, approximately half of the Canadian settlers remained permanently.[61] By 1900, 573,000 French Canadians had immigrated to New England.[62] These Canadians were the second biggest wave of immigration to hit New England after the Irish.

With a constantly growing immigrant population, these new Franco-Americans settled together in neighborhoods colloquially called Little Canada; after 1960 these faded away.[63] There were few French language institutions other than Catholic churches. There were some French newspapers, but they had a total of only 50,000 subscribers in 1935.[64] The World War II generation avoided bilingual education for their children, and insisted they speak English.[65] By 1976, nine in ten Franco Americans usually spoke English and scholars generally agreed that "the younger generation of Franco-American youth had rejected their heritage."[66]

Since 1900

Railroads

| |

|

The New Haven railroad was the leading carrier in New England from 1872 to 1968. New York's leading banker, J. P. Morgan, had grown up in Hartford and had a strong interest in the New England economy. Starting in the 1890s Morgan began financing the major New England railroads, such as the New Haven and the Boston and Maine, dividing territory so they would not compete. In 1903 he brought in Charles Mellen as president of the New Haven (1903-1913). The goal, richly supported by Morgan's financing, was to purchase and consolidate the main railway lines of New England, merge their operations, lower their costs, electrify the heavily used routes, and modernize the system. With less competition and lower costs, there supposedly would be higher profits. The New Haven purchased 50 smaller companies, including steetcars, freight steamers, passenger steamships, and a network of light rails (electrified trolleys) that provided inter-urban transportation for all of southern New England. By 1912, the New Haven operated over 2,000 miles (3,200 km) of track, with 120,000 employees, and practically monopolized traffic in a wide swath from Boston to New York City.

Morgan’s quest for monopoly angered reformers during the Progressive Era, most notably Boston lawyer Louis Brandeis, who fought the New Haven for years. Mellen’s abrasive tactics alienated public opinion, led to high prices for acquisitions and to costly construction. The accident rate rose when efforts were made to save on maintenance costs. Debt soared from $14 million in 1903 to $242 million in 1913. Also in 1913 it was hit by an anti-trust lawsuit by the federal government and was forced to give up its trolley systems.[67] The advent of automobiles, trucks and buses after 1910 slashed the profits of the New Haven. The line went bankrupt in 1935, was reorganized and reduced in scope, went bankrupt again in 1961, and in 1969 was merged into the Penn Central system, which itself went bankrupt. The remnants of the system are now part of Conrail.[68]

The automotive revolution came much faster than anyone expected, especially the railroad executives. In 1915 Connecticut had 40,000 automobiles; five years later it had 120,000. There was even faster growth in trucks from 7,000 to 24,000.[69]

Weather

In the 1930s and 1940s there were winter "outing clubs" in a number of areas in New England which held dog sled races, ski jumping, and cross country competitions; sulky races on cleared streets, and dances.[70]

The 1938 New England hurricane hit the region (and Long Island) hard, killing about 700 people. The U.S. Weather Bureau was mistaken in its predicted path and there was little warning. Many thousands of houses and buildings were damaged or destroyed. Local relief efforts were feeble, so Federal agencies took charge, and in the process created the modern disaster relief system.[71] It blew down 15,000,000 acres (61,000 km2) of trees, one-third of the total forest at the time in New England. 3 billion board feet were salvaged. Many of the older trees in the region are about 75 years old, dating from after this storm.[72]

Economy

The New England economy was radically transformed after World War II. The factory economy practically disappeared. The textile mills one by one went out of business from the 1920s to the 1970s. For example, the Crompton Company, after 178 years in business, went bankrupt in 1984, costing the jobs of 2,450 workers in five states. The major reasons were cheap imports, the strong dollar, declining exports, and a failure to diversify.[73] Shoes followed. What remains is very high technology manufacturing, such as jet engines, nuclear submarines, pharmaceuticals, robotics, scientific instruments, and medical devices. MIT (the Massachusetts Institute of Technology) invented the format for university-industry relations in high tech fields, and spawned many software and hardware firms, some of which grew rapidly.[74] By the 21st century the region had become famous for its leadership roles in the fields of education, medicine and medical research, high-technology, finance, and tourism.[75]

Famous leaders

Eight presidents of the United States have been born in New England, however only five are usually affiliated with the area. They are, in chronological order: John Adams (Massachusetts), John Quincy Adams (Massachusetts), Franklin Pierce (New Hampshire), Chester A. Arthur (born in Vermont, affiliated with New York), Calvin Coolidge (born in Vermont, affiliated with Massachusetts), John F. Kennedy (Massachusetts), George H. W. Bush (born in Massachusetts, affiliated with Texas) and George W. Bush (born in Connecticut, affiliated with Texas).

Nine vice presidents of the United States have been born in New England, however, again only five are usually affiliated with the area. They are, in chronological order: John Adams, Elbridge Gerry (Massachusetts), Hannibal Hamlin (Maine), Henry Wilson (born in New Hampshire, affiliated with Massachusetts), Chester A. Arthur, Levi P. Morton (born in Vermont, affiliated with New York), Calvin Coolidge, Nelson Rockefeller (born in Maine, affiliated with New York), George H.W. Bush.

Eleven of the Speakers of the United States House of Representatives have been elected from New England. They are, in chronological order: Jonathan Trumbull, Jr. (2nd Speaker, Connecticut), Theodore Sedgwick (5th Speaker, Massachusetts), Joseph Bradley Varnum (7th Speaker, Massachusetts), Robert Charles Winthrop (22nd Speaker, Massachusetts), Nathaniel Prentice Banks (25th Speaker, Massachusetts), James G. Blaine (31st Speaker, Maine), Thomas Brackett Reed (36th and 38th, Maine), Frederick Gillett (42nd, Massachusetts), Joseph William Martin, Jr. (49th and 51st, Massachusetts), John William McCormack (53rd, Massachusetts) and Tip O'Neill (55th, Massachusetts).

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bain, Angela Goebel; Manring, Lynne; and Mathews, Barbara. Native Peoples in New England. Retrieved July 21, 2010, from Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association.

- ^ "Abenaki History". abenakination.org. Retrieved 2011-03-28.

- ^ Allen, William (1849). The History of Norridgewock. Norridgewock ME: Edward J. Peet. p. 10. Retrieved 2011-03-28.

- ^ Wiseman, Fred M. "The Voice of the Dawn: An Autohistory of the Abenaki Nation". p. 70. Retrieved 2011-03-28.

- ^ Alfred W. Crosby, "Virgin Soil Epidemics as a Factor in the Aboriginal Depopulation in America," William and Mary Quarterly (1976), 33#2 pp. 289-299 in JSTOR

- ^ a b c Charles O. Paullin, Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States.; Edited by John K. Wright (1932), Plate 42

- ^ a b c William F. Swindler, ed. Sources and Documents of United States Constitutions. (1979) Vol. 10; Pps. 17-23.

- ^ Paullin, Charles O.; Atlas of the Historical Geography of the United States; Edited by John K. Wright; New York, New York and Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Institution of Washington and American Geographical Society of New York, 1932:Plate 42. ; Excellent section on International and interstate boundary disputes.

- ^ Swindler, William F.., ed. Sources and Documents of United States Constitutions 10 Volumes; Dobbs Ferry, New York; Oceana Publications, 1973–1979; Vol. 10; pp. 17–23; The most complete and up-to-date compilation for the states.

- ^ Van Zandt, Franklin K.; Boundaries of the United States and the Several States; Geological Survey Professional Paper 909. Washington, D.C.; Government Printing Office; 1976. The standard compilation for its subject.; Page 92.

- ^ "Canada quake shakes Vt". Burlington, Vermont: Burlington Free Press. 24 June 2010. pp. 1A, 4A.

- ^ Ernest Lee Tuveson, Redeemer nation: the idea of America's millennial role (University of Chicago Press, 1980)

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot (1972). The Oxford History of the American People. New York City: Mentor. p. 204. ISBN 0-451-62600-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Benjamin Woods Labaree, Colonial Massachusetts: a history (1979)

- ^ Dominion of New England

- ^ Daniel Scott Smith, "The Demographic History of Colonial New England," Journal of Economic History, 32 (March 1972), 165-183 in JSTOR

- ^ Terry L. Anderson and Robert Paul Thomas, "White Population, Labor Force and Extensive Growth of the New England Economy in the Seventeenth Century, Journal of Economic History, Vol. 33, No. 3 (Sept 1973), pp. 634-667 at p 647, 651; they use stable population models. in JSTOR

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot (1972). The Oxford History of the American People. New York City: Mentor. p. 112. ISBN 0-451-62600-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Anne Mackin, Americans and their land: the house built on abundance (University of Michigan Press, 2006) p 29

- ^ James Ciment, ed. Colonial America: An Encyclopedia of Social, Political, Cultural, and Economic History, 2005.

- ^ Margaret Alan Newell, "The Birth of New England in the Atlantic Economy: From its Beginning to 1770, in Peter Temin, ed., Engines of Enterprise: An Economic History of New England (Harvard UP, 2000), pp. 11-68, esp. p. 41

- ^ Morison, Samuel Eliot (1972). The Oxford History of the American People. New York City: Mentor. pp. 199–200. ISBN 0-451-62600-1.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Quoted in Claude H. Van Tine, The Causes of the War of Independence (1922) p 318

- ^ Gloria L. Main and Jackson T. Main, "The Red Queen in New England?," William and Mary Quarterly, Jan 1999, Vol. 56 Issue 1, pp 121-50 in JSTOR

- ^ "History of Boston Latin School—oldest public school in America". BLS Web Site. Archived from the original on 2007-05-02. Retrieved 2007-06-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Lawrence Creminm American Education: The Colonial Experience, 1607-1783 (Harper & Row, 1970)

- ^ Maris A. Vinovskis, "Family and Schooling in Colonial and Nineteenth-Century America," Journal of Family History," Jan 1987, Vol. 12 Issue 1-3, pp 19-37

- ^ "Schooling, Education, and Literacy, In Colonial America". faculty.mdc.edu. 2010-04-01. Archived from the original on 2011-01-10.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|month=and|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Small, Walter H. “The New England Grammar School, 1635-1700.” School Review 7 (September 1902): 513-31

- ^ James McLachlan, American boarding schools: A historical study (1970)

- ^ Arthur Powell, Lessons from Privilege: The American Prep School Tradition (Harvard UP, 1998)

- ^ John R. Thelin, A History of American Higher Education (2004) pp 1-40

- ^ Kathryn Kish Sklar, "The Schooling of Girls and Changing Community Values in Massachusetts Towns, 1750-1820," History of Education Quarterly 1993 33(4): 511-542

- ^ E. Jennifer Monaghan, "Literacy Instruction and Gender in Colonial New England," American Quarterly 1988 40(1): 18-41 in JSTOR

- ^ David Hackett Fischer, Paul Revere's Ride (1994)

- ^ John Ross[permanent dead link] "Dark Day of 1780," American Heritage, Fall 2008.

- ^ [1]

- ^ James Schouler, History of the United States vol 1 (1891; copyright expired).

- ^ "New England". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 2008-07-24.

- ^ Van Wyck Brooks, The flowering of New England, 1815-1865 (1941)

- ^ William R. Bagnall, The Textile Industries of the United States: Including Sketches and Notices of Cotton, Woolen, Silk, and Linen Manufacturers in the Colonial Period. (1893) Vol. I. Pg 97.

- ^ Thomas Dublin, "Lowell Millhands" in Transforming Women's Work (Cornell UP) pp 77-118.

- ^ a b c d Bidwell, p. 684.

- ^ Kelsey, p. 1.

- ^ Bidwell, p. 688.

- ^ Kelsey, p. 4.

- ^ a b Bidwell, p. 685.

- ^ Gates, p. 39-40.

- ^ Bidwell, p. 689.

- ^ Russell, p. vi.

- ^ Bidwell, p. 687.

- ^ a b Russell, p. 337.

- ^ Kelsey, p. 5.

- ^ Kelsey, p. 6.

- ^ Temin, p. 109.

- ^ [2]

- ^ Gerard J. Brault, The French-Canadian Heritage in New England (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 1986) pg 52-54

- ^ Claire Quintal, ed., Steeples and Smokestacks. A Collection of essays on The Franco-American Experience in New England (1996)

- ^ Sacha Richard, "American Perspectives on La fièvre aux États-Unis, 1860–1930: A Historiographical analysis of Recent Writings on the Franco-Americans in New England." Canadian Review of American Studies (2002) 32#1 pp: 105-132.

- ^ Iris Podea Saunders, "Quebec to 'Little Canada': The Coming of the French Canadians to New England in the Nineteenth Century," New England Quarterly (1950) 23#3 pp. 365-380 in JSTOR

- ^ Brault, The French-Canadian Heritage in New England pg.52

- ^ Roby, Yves. The Franco-Americans of New England: Dreams and Realities. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2004 pg.42

- ^ Quintal pp 618-9

- ^ Quintal p 614

- ^ Quintal p 618

- ^ Richard, "American Perspectives on La fièvre aux États-Unis, 1860–1930," p 105, quote on p 109

- ^ Vincent P. Carosso (1987). The Morgans: Private International Bankers, 1854-1913. Harvard UP. pp. 607–10.

- ^ John L. Weller, The New Haven Railroad: its rise and fall (1969)

- ^ Peter Temin, ed., Engines of Enterprise: An Economic History of New England (2000) p 185

- ^ Barel, Gerry (April 2011). "Ski Jumping Article Brings Back Memories for a Reader". Vermont's Northland Journal. 10 (1): 31.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Lourdes B. Aviles, Taken by Storm, 1938: A Social and Meteorological History of the Great New England Hurricane (2012)

- ^ Long, Stephen (September 7, 2011). "Remembering the hurricane of 1938". the Chronicle. Barton, Vermont. p. 3.

- ^ Timothy J. Minchin, "The Crompton Closing: Imports and the Decline of America's Oldest Textile Company, Journal of American Studies (2013) 47#1 pp 231-260 online.

- ^ Henry Etzkowitz, MIT and the Rise of Entrepreneurial Science (Routledge 2007)

- ^ David Koistinen, Confronting Decline: The Political Economy of Deindustrialization in Twentieth-Century New England (2013)

Bibliography

- Feintuch, Burt and David H. Watters, eds. Encyclopedia of New England (2005), comprehensive coverage by scholars; 1596pp

- Adams, James Truslow. The Founding of New England (1921) online edition; Revolutionary New England, 1691–1776 (1923); New England in the Republic, 1776–1850 (1926)

- Andrews, Charles M. The Fathers of New England: A Chronicle of the Puritan Commonwealths (1919), short survey. online edition

- Axtell, James, ed. The American People in Colonial New England (1973), new social history

- Bidwell, Percy. “The Agricultural Revolution in New England. The American Historical Review, Vol. 26, No. 4. American Historical Association, July 1921. <http://people.brandeis.edu/~dkew/David/Bidwell-agriculture-1921.pdf>

- Black, John D. The rural economy of New England: a regional study (1950) online

- Brewer, Daniel Chauncey. Conquest of New England by the Immigrant (1926).

- Buell, Lawrence. New England Literary Culture: From Revolution through Renaissance. (Cambridge University Press, 1986), a literary history of New England. ISBN 0-521-37801-X

- Conforti, Joseph A. Imagining New England: Explorations of Regional Identity from the Pilgrims to the Mid-Twentieth Century (2001)

- Cumbler, John T. Reasonable Use: The People, the Environment, and the State, New England, 1790–1930 (2001), environmental history

- Daniels, Bruce. New England Nation (2012) 256pp; focus on Puritans

- Judd, Richard W. Second Nature: An Environmental History of New England (University of Massachusetts Press, 2014) xiv, 327 pp.

- Karlsen, Carol F. The Devil in the Shape of a Woman: Witchcraft in Colonial New England (1998)

- Kelsey, Darwin, ed. “Agriculture in New England, 1790-1840.” Old Sturbridge Village Research Paper. Old Sturbridge, Inc., January 1973.

- Koistinen, David. "Business and Regional Economic Decline: The Political Economy of Deindustrialization in Twentieth-Century New England" Business and economic history online (2014) #12

- Lockridge, Kenneth A. A New England Town: The First Hundred Years: Dedham, Massachusetts, 1636–1736 (1985), new social history

- McWilliams, John. New England's Crisis and Cultural Memory: Literature, Politics, History, Religion, 1620–1860. (Cambridge University Press, 2009) excerpt and text search

- McPhetres, S. A. A political manual for the campaign of 1868, for use in the New England states, containing the population and latest election returns of every town (1868)

- Newell; Margaret Ellen. From Dependency to Independence: Economic Revolution in Colonial New England (Cornell UP, 1998) online edition

- Old Colony Trust Company, New England: Old and New, Cambridge : University Press, 1920

- Palfrey, John Gorham. History of New England (5 vol 1859–90), classic narrative to 1775; online

- Richard, Mark Paul. Not a Catholic Nation: The Ku Klux Klan Confronts New England in the 1920s (University of Massachusetts Press, 2015). x, 259 pp.

- Russell, Howard. A Long, Deep Furrow: Three Centuries of Farming in New England (University Press of New England, 1976)

- Sletcher, Michael, ed. New England: The Greenwood Encyclopedia of American Regional Cultures (2004), articles on culture and society by experts

- Temin, Peter, ed. Engines of Enterprise: An Economic History of New England (Harvard UP, 2000) online edition

- Tucker, Spencer, ed. American Civil War: A State-by-State Encyclopedia (2 vol 2015) 1019pp excerpt

- Vaughan, Alden T. New England Frontier: Puritans and Indians 1620–1675 (1995)

- Weeden, William Babcock, "Economic and Social History of New England, 1620-1789" (2 vol. 1890), old but highly detailed and reliable

- Zimmerman, Joseph F. The New England Town Meeting: Democracy in Action (1999)

Primary sources

- Dwight, Timothy. Travels Through New England and New York (circa 1800) 4 vol. (1969) Online at: vol 1; vol 2; vol 3; vol 4

- Who's who in New England. A.N. Marquis. 1915. p. 1.