Gerrymandering in the United States: Difference between revisions

| Line 85: | Line 85: | ||

The predominant voting system in the United States is a [[First-past-the-post voting|first-past-the-post]] system that requires the existence of single-member districts. Various alternative [[Plurality voting system|district-based voting systems]] that do not rely on redistricting have been proposed that may mitigate against the ability to gerrymander. These systems typically involve a form of at-large elections or multimember districts. Examples of such systems include the [[Single transferable vote|single-transferable vote]], [[cumulative voting]], and [[limited voting]].<ref name=WayOut>''See generally'' {{cite journal|last=Mulroy|first=Steven J.|title=The Way Out: A Legal Standard for Imposing Alternative Electoral Systems as Voting Rights Remedies|journal=Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review|year=1998|volume=33|ssrn=1907880|accessdate=}}</ref> |

The predominant voting system in the United States is a [[First-past-the-post voting|first-past-the-post]] system that requires the existence of single-member districts. Various alternative [[Plurality voting system|district-based voting systems]] that do not rely on redistricting have been proposed that may mitigate against the ability to gerrymander. These systems typically involve a form of at-large elections or multimember districts. Examples of such systems include the [[Single transferable vote|single-transferable vote]], [[cumulative voting]], and [[limited voting]].<ref name=WayOut>''See generally'' {{cite journal|last=Mulroy|first=Steven J.|title=The Way Out: A Legal Standard for Imposing Alternative Electoral Systems as Voting Rights Remedies|journal=Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review|year=1998|volume=33|ssrn=1907880|accessdate=}}</ref> |

||

[[Proportional representation|Proportional voting systems]], such as those used in all but three European states, would bypass the problem altogether. In these systems, no districts are present, and the party that gets, for example, 30 percent of the votes gets roughly 30 percent of the seats in the legislature. Although it is common for European states to have more than two parties, the American two-party system could be maintained by implementing a sufficiently high [[election threshold]]. The problem with |

[[Proportional representation|Proportional voting systems]], such as those used in all but three European states, would bypass the problem altogether. In these systems, no districts are present, and the party that gets, for example, 30 percent of the votes gets roughly 30 percent of the seats in the legislature. Although it is common for European states to have more than two parties, the American two-party system could be maintained by implementing a sufficiently high [[election threshold]]. The problem with [[Proportional representation|Proportional voting systems]] is the breaking of the strong constituency link, a cornerstone of the American system.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.aceproject.org/ace-en/topics/es/esd/esd02/esd02c/esd02c01/|title=Advantages and disadvantages of List PR|publisher=www.aceproject.org ACE Project}}</ref> |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 15:18, 24 March 2017

Gerrymandering in the United States has been practiced since the founding of the country to strengthen the power of particular political interests within legislative bodies. Partisan gerrymandering is commonly used to increase the power of a political party. In some instances, political parties collude to protect incumbents by engaging in bipartisan gerrymandering. After racial minorities were enfranchised, some jurisdictions engaged in racial gerrymandering to weaken the political power of racial minority voters, while others engaged in racial gerrymandering to strengthen the power of minority voters. Throughout the 20th century, courts have grappled with the legality of these types of gerrymandering and have devised different standards for the different types of gerrymandering. Various legal and political remedies have emerged to prevent gerrymandering, including court-ordered redistricting plans, redistricting commissions, and alternative voting systems that do not depend on drawing boundaries for single-member electoral districts.

Types

| This article is part of a series on the |

| United States House of Representatives |

|---|

|

| History of the House |

| Members |

|

|

| Congressional districts |

| Politics and procedure |

| Places |

|

|

Political

Partisan

History

Partisan gerrymandering, which refers to redistricting that favors one political party, has a long tradition in the United States that precedes the 1789 election of the First U.S. Congress. In 1788, Patrick Henry and his Anti-Federalist allies were in control of the Virginia House of Delegates. They drew the boundaries of Virginia's 5th congressional district in an unsuccessful attempt to keep James Madison out of the U.S. House of Representatives.[1]

The word gerrymander (originally written "Gerry-mander") was used for the first time in the Boston Gazette on 26 March 1812. The word was created in reaction to a redrawing of Massachusetts state senate election districts under the then-governor Elbridge Gerry (pronounced /ˈɡɛri/; 1744–1814). In 1812, Governor Gerry signed a bill that redistricted Massachusetts to benefit his Democratic-Republican Party. When mapped, one of the contorted districts to the north of Boston was said to resemble the shape of a salamander.[2] Gerrymander is a portmanteau of the governor's last name and the word salamander. The redistricting was a notable success. In the 1812 election, both the Massachusetts House and governorship were won by Federalists by a comfortable margin (costing Gerry his position), but the senate remained firmly in Democratic-Republican hands.[2]

The coiner of the term "gerrymander" may never be firmly established. Historians widely believe that the Federalist newspaper editors Nathan Hale, and Benjamin and John Russell were the instigators, but the historical record does not have definitive evidence as to who created or uttered the word for the first time.[3] Appearing with the term, and helping to spread and sustain its popularity, was a political cartoon depicting a strange animal with claws, wings and a dragon-like head satirizing the map of the odd-shaped district. This cartoon was most likely drawn by Elkanah Tisdale, an early 19th-century painter, designer, and engraver who was living in Boston at the time.[3] The word gerrymander was reprinted numerous times in Federalist newspapers in Massachusetts, New England, and nationwide during the remainder of 1812.

Gerrymandering soon began to be used to describe not only the original Massachusetts example, but also other cases of district-shape manipulation for partisan gain in other states. The first known use outside the immediate Boston area came in the Newburyport Herald of Massachusetts on 31 March, and the first known use outside Massachusetts came in the Concord Gazette of New Hampshire on 14 April 1812. The first known use outside New England came in the New York Gazette & General Advertiser on 19 May. What may be the first use of the term to describe the redistricting in another state (Maryland) occurred in the Federal Republican (Georgetown, Washington, DC) on 12 October 1812. There are at least 80 known citations of the word from March through December 1812 in American newspapers.[3]

The practice of gerrymandering the borders of new states continued past the Civil War and into the late 19th century. The Republican Party used its control of Congress to secure the admission of more states in territories friendly to their party. A notable example is the admission of Dakota Territory as two states instead of one. By the rules for representation in the Electoral College, each new state carried at least three electoral votes, regardless of its population.

The ability to gerrymander can create strange bedfellows interested in securing re-election; in some states, Republicans have cut deals with opposing black Democratic state legislators to create majority-black districts. By packing black Democratic voters into a single district, they can essentially ensure the election of a black Congressman or re-election of a black state legislator due to the packed concentration of Democratic voters. However, the surrounding districts are more safely Republican in areas like the South, where white conservatives have increasingly shifted from the Democratic to the Republican Party in national elections in the last four decades.

In Pennsylvania, the Republican-dominated state legislature used gerrymandering to help defeat Democratic representative Frank Mascara. Mascara was elected to Congress in 1994. In 2002, the Republican Party altered the boundaries of his original district so much that he was pitted against fellow Democratic candidate John Murtha in the election. The shape of Mascara's newly drawn district formed a finger that stopped at his street, encompassing his house, but not the spot where he parked his car. Murtha won the election in the newly formed district.[4]

State legislatures have used gerrymandering along racial or ethnic lines both to decrease and increase minority representation in state governments and congressional delegations. In the state of Ohio, a conversation between Republican officials was recorded that demonstrated that redistricting was being done to aid their political candidates. Furthermore, the discussions assessed race of voters as a factor in redistricting, because African-Americans had backed Democratic candidates. Republicans apparently removed approximately 13,000 African-American voters from the district of Jim Raussen, a Republican candidate for the House of Representatives, in an attempt to tip the scales in what was once a competitive district for Democratic candidates.[5]

International election observers from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, who were invited to observe and report on the 2004 national elections, expressed criticism of the U.S. congressional redistricting process and made a recommendation that the procedures be reviewed to ensure genuine competitiveness of Congressional election contests.[6]

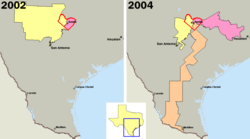

From time to time, other names are given the "-mander" suffix to tie a particular effort to a particular politician or group. These include "Jerrymander" (a reference to California Governor Jerry Brown),[7] and "Perrymander" (a reference to Texas Governor Rick Perry).[8][9]

Legality

In Davis v. Bandemer (1986), the Supreme Court held that partisan gerrymandering violated the Equal Protection Clause, but the court could not agree on the appropriate constitutional standard against which legal claims of partisan gerrymandering should be evaluated. Writing for a plurality of the Court, Justice White said that partisan gerrymandering occurred when a redistricting plan was enacted with both the intent and the effect of discriminating against an identifiable political group. Justices Powell and Stevens said that partisan gerrymandering should be identified based on multiple factors, such as electoral district shape and adherence to local government boundaries. Justices O'Connor, Burger, and Rehnquist disagreed with the view that partisan gerrymandering claims were justiciable and would have held that such claims should not be recognized by courts.[10]: 777–779 Lower courts found it difficult to apply Bandemer, and only in one subsequent case, Party of North Carolina v. Martin (1992),[11] did a lower court strike down a redistricting plan on partisan gerrymandering grounds.[10]: 783

The Supreme Court revisited the concept of partisan gerrymandering claims in Vieth v. Jubelirer (2004).[12] The justices divided, and no clear standard against which to evaluate partisan gerrymandering claims emerged. Writing for a plurality, Justice Scalia said that partisan gerrymandering claims were nonjusticiable. A majority of the court would continue to allow partisan gerrymandering claims to be considered justiciable, but those Justices had divergent views on how such claims should be evaluated.[10]: 819–821

In Whitford v Gill (2016)[13] a District Court used the efficiency gap statistic to evaluate the claim of partisan gerrymander in Wisconsin's legislative districts. In the 2012 election for the state legislature, the efficiency gap was 11.69% to 13% in favor of the Republicans. Republican candidates had 48.6% of the two-party votes for state Representative but won 61% of the 99 districts. The court found that the disparate treatment of Democratic and Republican voters violated the 1st and 14th amendments to the US Constitution.[14]

Bipartisan

Bipartisan gerrymandering refers to redistricting that favors the incumbents in both the Democratic and Republican Parties. Bipartisan gerrymandering became a salient practice in the 2000 redistricting process, which created some of the most non-competitive redistricting plans in American history.[10]: 828 The Supreme Court held in Gaffney v. Cummings (1973) that bipartisan gerrymanders are constitutionally permissible under the Equal Protection Clause.[10]: 828 [15]

Racial

Negative

"Negative racial gerrymandering" refers to a process in which district lines are drawn to prevent racial minorities from electing their preferred candidates.[16]: 26 Between the Reconstruction Era and mid-20th century, white Southern Democrats effectively controlled redistricting throughout the Southern United States. In areas where some African-American and other minorities succeeded in registering, some states created districts that were gerrymandered to reduce the voting impact of minorities. Minorities were effectively deprived of their franchise into the 1960s. With the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and its subsequent amendments, redistricting that had the effect of reducing the political influence of a racial or language minority group was prohibited.

Affirmative

While the Equal Protection Clause, along with Section 2 and Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act, prohibit jurisdictions from gerrymandering electoral districts to dilute the votes of racial groups, the Supreme Court has held that in some instances, the Equal Protection Clause prevents jurisdictions from drawing district lines to favor racial groups. The Supreme Court first recognized these "affirmative racial gerrymandering" claims in Shaw v. Reno (Shaw I) (1993),[17] holding that plaintiffs "may state a claim by alleging that [redistricting] legislation, though race neutral on its face, rationally cannot be understood as anything other than an effort to separate voters into different districts on the basis of race, and that the separation lacks sufficient justification". The Supreme Court reasoned that these claims were cognizable because relying on race in redistricting "reinforces racial stereotypes and threatens to undermine our system of representative democracy by signaling to elected officials that they represent a particular racial group rather than their constituency as a whole".[17]: 649–650 [18]: 620 Later opinions characterized the type of unconstitutional harm created by racial gerrymandering as an "expressive harm",[10]: 862 which law professors Richard Pildes and Richard Neimi have described as a harm "that results from the idea or attitudes expressed through a governmental action."[19]

Subsequent cases further defined the counters of racial gerrymandering claims and how those claims relate to the Voting Rights Act. In United States v. Hays (1996),[20] the Supreme Court held that only those persons who reside in a challenged district may bring a racial gerrymandering claim.[18]: 623 [20]: 743–744 In Miller v. Johnson (1995),[21] the Supreme Court held that a redistricting plan must be subjected to strict scrutiny if the jurisdiction used race as the "predominant factor" in determining how to draw district lines. The court defined "predominance" as meaning that the jurisdiction gave more priority to racial considerations than to traditional redistricting principles such as "compactness, contiguity, [and] respect for political subdivisions or communities defined by actual shared interests."[18]: 621 [21]: 916 In determining whether racial considerations predominated over traditional redistricting principles, courts may consider both direct and circumstantial evidence of the jurisdiction's intent in drawing the district lines, and irregularly-shaped districts constitute strong circumstantial evidence that the jurisdiction relied predominately on race.[10]: 869 If a court concludes that racial considerations predominated, then a redistricting plan is considered a "racially gerrymandered" plan and must be subjected to strict scrutiny, meaning that the redistricting plan will be upheld as constitutional only if it is narrowly tailored to advance a compelling state interest. In Bush v. Vera (1996),[22]: 983 the Supreme Court in a plurality opinion assumed that compliance with Section 2 or Section 5 of the Act constituted compelling interests, and lower courts have treated these two interests as the only compelling interests that may justify the creation of racially gerrymandered districts.[10]: 877

In Hunt v. Cromartie (1999), the Supreme Court approved a racially focused gerrymandering of a congressional district on the grounds that the definition was not pure racial gerrymandering but instead partisan gerrymandering, which is constitutionally permissible. With the increasing racial polarization of parties in the South in the U.S. as conservative whites move from the Democratic to the Republican Party, gerrymandering may become partisan and also achieve goals for ethnic representation.

Various examples of affirmative racial gerrymandering have emerged. When the state legislature considered representation for Arizona's Native American reservations, they thought each needed their own House member, because of historic conflicts between the Hopi and Navajo nations. Since the Hopi reservation is completely surrounded by the Navajo reservation, the legislature created an unusual district configuration for the 2nd congressional district that featured a fine filament along a river course several hundred miles in length to attach the Hopi reservation to the rest of the district; the arrangement lasted until 2013. The California state legislature created a congressional district (2003-2013) that extended over a narrow coastal strip for several miles. It ensured that a common community of interest will be represented, rather than having portions of the coastal areas be split up into districts extending into the interior, with domination by inland concerns.

In the case of League of United Latin American Citizens v. Perry, the United States Supreme Court upheld on 28 June 2006, most of a Texas congressional map suggested in 2003 by former United States House Majority Leader Tom DeLay, and enacted by the state of Texas.[23] The 7–2 decision allows state legislatures to redraw and gerrymander districts as often as they like (not just after the decennial census). Thus they may work to protect their political parties' standing and number of seats, so long as they do not harm racial and ethnic minority groups. A 5–4 majority declared one Congressional district unconstitutional in the case because of harm to an ethnic minority.

Remedies

The United States is alone among major countries in that self-interested politicians govern the redistricting process.[10]: 820 Various political and legal remedies have been used or proposed to diminish or prevent gerrymandering in the country.

Neutral redistricting criteria

Various constitutional and statutory provisions may compel a court to strike down a gerrymandered redistricting plan. At the federal level, the Supreme Court has held that if a jurisdiction’s redistricting plan violates the Equal Protection Clause or Voting Rights Act of 1965, a federal court must order the jurisdiction to propose a new redistricting plan that remedies the gerrymandering. If the jurisdiction fails to propose a new redistricting plan, or its proposed redistricting plan continues to violate the law, then the court itself must draw a redistricting plan that cures the violation and use its equitable powers to impose the plan on the jurisdiction.[10]: 1058 [24]: 540

In the Supreme Court case of Karcher v. Daggett (1983),[25] a New Jersey redistricting plan was overturned when it was found to be unconstitutional by violating the constitutional principle of one person, one vote. Despite the state claiming its unequal redistricting was done to preserve minority voting power, the court found no evidence to support this and deemed the redistricting unconstitutional.[26]

At the state level, state courts may order or impose redistricting plans on jurisdictions where redistricting legislation prohibits gerrymandering. For example, in 2010 Florida adopted two state constitutional amendments that prohibit the Florida Legislature from drawing redistricting plans that favor or disfavor any political party or incumbent.[27]

A Tufts University professor has proposed the use of metric geometry to measure gerrymandering for forensic purposes.[28]

Redistricting commissions

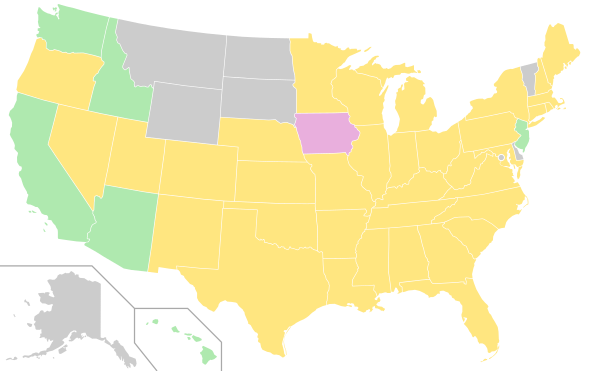

Rather than allowing more political influence, some states have shifted redistricting authority from politicians and given it to non-partisan redistricting commissions. The states of Washington,[29] Arizona,[30] and California have created standing committees for redistricting following the 2010 census. Rhode Island[31] and the New Jersey Redistricting Commission have developed ad hoc committees, but developed the past two decennial reapportionments tied to new census data.

The Arizona State Legislature challenged the constitutionality of the use of a non-partisan commission, rather than the legislature, for redistricting. In Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission, the US Supreme Court in 2015 upheld the constitutionality of non-partisan commissions.[32]

Alternative voting systems

The predominant voting system in the United States is a first-past-the-post system that requires the existence of single-member districts. Various alternative district-based voting systems that do not rely on redistricting have been proposed that may mitigate against the ability to gerrymander. These systems typically involve a form of at-large elections or multimember districts. Examples of such systems include the single-transferable vote, cumulative voting, and limited voting.[33]

Proportional voting systems, such as those used in all but three European states, would bypass the problem altogether. In these systems, no districts are present, and the party that gets, for example, 30 percent of the votes gets roughly 30 percent of the seats in the legislature. Although it is common for European states to have more than two parties, the American two-party system could be maintained by implementing a sufficiently high election threshold. The problem with Proportional voting systems is the breaking of the strong constituency link, a cornerstone of the American system.[34]

See also

- Gerrymandering

- California redistricting propositions

- Electoral geography

- Checkerboarding (land)

References

- ^ Labunski, Richard. James Madison and the Struggle for the Bill of Rights, New York: Oxford University Press, 2006

- ^ a b Griffith, Elmer (1907). The Rise and Development of the Gerrymander. Chicago: Scott, Foresman and Co. pp. 72–73. OCLC 45790508.

- ^ a b c Martis, Kenneth C. (2008). "The Original Gerrymander". Political Geography. 27 (4): 833–839. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2008.09.003.

- ^ Thomas Lloyd Brunell (2008). Redistricting and Representation: Why Competitive Elections Are Bad for America. Psychology Press. p. 69. ISBN 9780415964524. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- ^ "Republican Party Politics (Part II)". WCPO. 29 April 2002. Archived from the original on May 20, 2002.

- ^ "XI" (PDF). Retrieved 2009-08-05.

- ^ Thomas B. Hofeller, "The Looming Redistricting Reform; How will the Republican Party Fare?", Politico, 2011.

- ^ David Wasserman (19 August 2011). "'Perrymander': Redistricting Map That Rick Perry Signed Has Texas Hispanics Up in Arms". National Journal. Archived from the original on 2012-01-16.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Mark Gersh (21 September 2011). "Redistricting Journal: Showdown in Texas—reasons and implications for the House, and Hispanic vote". CBS News. Archived from the original on 2011-09-22. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Issacharoff, Samuel; Karlan, Pamela S.; Pildes, Richard H. (2012). The Law of Democracy: Legal Structure of the Political Process (4th ed.). Foundation Press. ISBN 1-59941-935-1.

- ^ Party of North Carolina v. Martin, 980 F.2d 943 (4th Cir. 1992)

- ^ Vieth v. Jubelirer, 541 U.S. 267 (2004)

- ^ Whitford v Gill decision

- ^ Wines, Michael (Nov 21, 2016). "Judges Find Wisconsin Redistricting Unfairly Favored Republicans". New York Times. Retrieved 2016-11-22.

- ^ Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735 (1973)

- ^ Whitby, Kenny J. (December 21, 2000). The Color of Representation: Congressional Behavior and Black Interests. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472087029.

- ^ a b Shaw v. Reno (Shaw I), 509 U.S. 630 (1993)

- ^ a b c Ebaugh, Nelson (1997). "Refining the Racial Gerrymandering Claim: Bush v. Vera". Tulsa Law Journal. 33 (2). Retrieved December 30, 2013.

- ^ Pildes, Richard; Niemi, Richard (1993). "Expressive Harms, "Bizarre Districts," and Voting Rights: Evaluation Election-District Appearances after Shaw v. Reno". Michigan Law Review. 92. JSTOR 1289795.

- ^ a b United States v. Hays, 515 U.S. 737 (U.S. 1995)

- ^ a b Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900 (1995).

- ^ Bush v. Vera 517 U.S. 952 (1996).

- ^ "High court upholds most of Texas redistricting map". CNN. Associated Press. 28 June 2006.

- ^ Wise v. Lipscomb, 437 U.S. 535(1978)

- ^ Karcher v. Daggett, 462 U.S. 725 (1983)

- ^ "Karcher v. Daggett – 462 U.S. 725 (1983)". Justia: US Supreme Court Center.

- ^ "Election 2010: Palm Beach County & Florida Voting, Candidates, Endorsements | The Palm Beach Post". Projects.palmbeachpost.com. Archived from the original on 2010-12-08. Retrieved 2010-12-19.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Meet the Math Professor Who's Fighting Gerrymandering With Geometry". The Chronicle of Higher Education. 2017-02-22. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- ^ Washington State Redistricting Commission "Washington State Redistricting Commission". Redistricting.wa.gov. Retrieved 2009-08-05.

- ^ Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission "Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission". Azredistricting.org. Retrieved 2009-08-05.

- ^ Rhode Island Reapportionment Commission Archived 18 October 2007.

- ^ 576 U.S. ___, June 2015 (link to slip opinion), retrieved 2015-07-05.

- ^ See generally Mulroy, Steven J. (1998). "The Way Out: A Legal Standard for Imposing Alternative Electoral Systems as Voting Rights Remedies". Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review. 33. SSRN 1907880.

- ^ "Advantages and disadvantages of List PR". www.aceproject.org ACE Project.

External links

Media related to Gerrymandering in the United States at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gerrymandering in the United States at Wikimedia Commons- [1], Google + GIS map showing congressional districts. Click ‘Map Tips’.

- African-American history

- Legislative districts of the United States

- Ethically disputed political practices

- Gerrymandering

- History of voting rights in the United States

- Political corruption in the United States

- Political terminology of the United States

- United States congressional districts

- Voter suppression

- Voting systems