Annexation of Junagadh: Difference between revisions

as per WP:MASSR 'and' current version is unsourced and unacceptable Tag: nowiki added |

Sicilianbro2 (talk | contribs) restructuring and adding additional citations |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

{{Use dmy dates|date=June 2017}} |

{{Use dmy dates|date=June 2017}} |

||

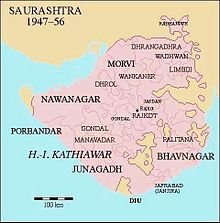

[[File:SaurashtraKart.jpg|thumb|Location of [[Junagadh State]] in [[Saurashtra (region)|Saurashtra]], among all the princely states shown in pink.]] |

[[File:SaurashtraKart.jpg|thumb|Location of [[Junagadh State]] in [[Saurashtra (region)|Saurashtra]], among all the princely states shown in pink.]] |

||

Junagadh was one of the princely states of India. Its mostly Hindu population of eighty percent was ruled by a Muslim Nawab (ruler). The state bordered India but his state to Pakistan had sea links with the Muslim state of Pakistan. A mirror image of Kashmir, its Muslim ruler acceded to Pakistan in spite of his Hindu subjects' wishes at the guidance of his pro-Pakistan chief minister Sir Shahnawaz Bhutto.<ref name="Jones2003">{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=t8iYEgPYG_EC&pg=PA69|title=Pakistan: Eye of the Storm|publisher=Yale University Press|year=2003|isbn=978-0-300-10147-8|pages=69–|author=Owen Bennett Jones}}</ref> |

|||

In the words of scholar Rakesh Ankit the Indian state's action in Junagadh was just another instance of India using force to incorporate princely states and Indian Muslims into India.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 371 <nowiki>''</nowiki>The mobilisation of Indian defence forces in the lead up to the accession of Junagadh in November 1947 and the management of violence directed at Junagadh’s Muslims afterwards are yet another instance of the forcible incorporation of Indian princely states and Indian Muslims into the reconstructed post-colonial state.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

|||

India |

India did not accept the accession, blockaded Junagadh and then invaded it. India imposed a plebiscite and gained its desired result, making Junagadh its part after a vote in its favour.<ref name="Jones2003" /> In the words of scholar Rakesh Ankit the Indian state's action in Junagadh was just another instance of India using force to incorporate princely states and Indian Muslims into India.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 371 <nowiki>''</nowiki>The mobilisation of Indian defence forces in the lead up to the accession of Junagadh in November 1947 and the management of violence directed at Junagadh’s Muslims afterwards are yet another instance of the forcible incorporation of Indian princely states and Indian Muslims into the reconstructed post-colonial state.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

The second instance was India’s alarmist claims about Junagadh’s military capability and help it received from Pakistan.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 403 <nowiki>''</nowiki> Second, the alarmist claims about Junagadh’s military capability and help from Pakistan<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

India took liberties with facts and laws on at least three occasions in Junagadh’s case. The question of Mangrol’s accession to India provided Patel and Menon with the ‘thin end of the wedge’ to pressurise Junagadh as India meted out ‘rough’ treatment on Junagadh’s sub-states.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 403 <nowiki>''</nowiki>In at least three instances in the case of Junagadh during the period under consideration, New Delhi took liberties with facts on ground and laws on paper, instances which have been either overlooked or explained since but not questioned. First, the question of Mangrol’s accession to India which provided the all-important thin end of the wedge for Patel and Menon to apply pressure on Junagadh. The existence of ‘sub-states’ within Junagadh was critical to the entire dynamic of the controversy and their ‘rough and ready’ treatment by the Indian state is exemplary of the manner in which the thicket of colonial complexities was cut through for post-colonial state reconstruction.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> The second instance was India’s alarmist claims about Junagadh’s military capability and help it received from Pakistan.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 403 <nowiki>''</nowiki> Second, the alarmist claims about Junagadh’s military capability and help from Pakistan<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> The third instance was the way India carried out the plebiscite in Junagadh as it acted as the judge, jury and executioner of the entire case.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 403 <nowiki>''</nowiki>third, the haste with which a plebiscite was arranged making India the judge, jury and executioner of the whole case.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

==Background== |

==Background== |

||

| Line 20: | Line 18: | ||

When Hall expressed this concern to V.P. Menon, Secretary at the Ministry of States, Menon dismissed these reservations. He responded to Hall, indicating India's feelings on Junagadh:<ref name=":1" /><blockquote>Junagadh is a state which proposes to accede to Pakistan...Import into Junagadh of large quantities of arms without the knowledge of [New Delhi] will be a direct threat to the...whole Kathiawar...We may justifiably claim that the question of self-preservation is involved in the proper restriction of arms traffic between Junagadh and foreign countries. On the question of how best to take preventive action, I would only emphasise that our measures should not be half-hearted.</blockquote>It took Pakistan a month to accept Junagadh's accession. By 15 August, Junagadh's transport and communication links had come under Indian hands.<ref name=":1" /> |

When Hall expressed this concern to V.P. Menon, Secretary at the Ministry of States, Menon dismissed these reservations. He responded to Hall, indicating India's feelings on Junagadh:<ref name=":1" /><blockquote>Junagadh is a state which proposes to accede to Pakistan...Import into Junagadh of large quantities of arms without the knowledge of [New Delhi] will be a direct threat to the...whole Kathiawar...We may justifiably claim that the question of self-preservation is involved in the proper restriction of arms traffic between Junagadh and foreign countries. On the question of how best to take preventive action, I would only emphasise that our measures should not be half-hearted.</blockquote>It took Pakistan a month to accept Junagadh's accession. By 15 August, Junagadh's transport and communication links had come under Indian hands.<ref name=":1" /> |

||

| ⚫ | Gopalaswami Ayyangar and Mountbatten agreed that Junagadh's accession to Pakistan was legally correct but Sardar Patel demanded that the decision of accession be in the hands of the people instead of the ruler.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 381 <nowiki>''</nowiki>While Ayyangar and Mountbatten concurred that Junagadh’s geographical contiguity could not have ‘any standing in law’, that is, it was ‘strictly and legally correct’ for it to have joined Pakistan, Patel retorted by arguing that people of a state should decide and not its ruler.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> Nehru layed out India's position. This position was that India did not accept Junagadh's accession to Pakistan, disagreed on the constitutional position of Mangrol and Babariawad and therefore wanted Junagadh to withdraw its forces from these two areas. As it would be unlikely that Junagadh would withdraw its forces from there, India would send its own troops there. Nehru did not favour going to war and invited Pakistan to allow a referendum under impartial auspices in Junagadh.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 383</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | On 20 September, Mountbatten asserted that Junagadh's accession to Pakistan was in violation of the principles of Partition and also claimed that Junagadh was making 'large-scale' military operations and causing its neighbours to become apprehensive. Thus, Mountbatten claimed that India would send ‘a small force as a very natural precautionary counter-measure’. However, to Junagadh the Indian forces did not appear to be a precautionary measure but as signs of an impending attack. Bhutto requested Pakistan for help.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 377</ref> Pakistan termed the buildup of the presence of Indian troops on Junagadh's borders a hostile act and an enroachment on Junagadh's sovereignty.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 377 <nowiki>''</nowiki> Jinnah sent a telegram to Mountbatten on 19 September and, pointing to the ‘large troop concentrations along the borders of Junagadh’, termed ‘any encroachment on Junagadh’s sovereignty or its territory…a hostile act’. In Delhi, the same day, Liaquat discussed Junagadh with Ismay<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

| ⚫ | At their meeting on 24 September, legal adviser Monckton told Mountbatten that since Junagadh had signed an instrument of accession to Pakistan there was no military way of changing this and Pakistan's consent would need to be obtained for any plebiscite India wished to conduct in Junagadh.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 380 <nowiki>''</nowiki>So far so good, but Monckton had also informed Mountbatten that as Junagadh had signed an instrument of accession to Pakistan, there was no military means of annulling this and Pakistan’s recognition of any plebiscite that India may conduct had to be obtained.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

== Mangrol and Babariawad == |

== Mangrol and Babariawad == |

||

Menon met the Sheikh of Mangrol, a state of 42 villages under the suzeranity of Junagadh. Menon lured the Sheikh (ruler) of Mangrol, with promises of autonomy and control of villages even inside Junagadh, to accede to India on 20 September. However, the Sheikh withdrew his accession to India the very next day. According to scholar Rakesh Ankit this throws light on Menon's use of pressure and even threat in regards to small principalities.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 377 <nowiki>''</nowiki>More importantly, on his way back, Menon stopped at Rajkot where the Muslim (and not Hindu)47 Sheikh of Mangrol, a state of 42 villages half of which were under Junagadh’s jurisdiction, had been summoned to meet him. Menon lured the Sheikh with promises of autonomy and rights even in regard to the villages under Junagadh and prevailed upon him to sign an instrument of accession on 20 September. However, the Sheikh withdrew it the very next day in a telegram to the Regional Commissioner of Rajkot, which throws some light on Menon’s modus operandi vis-à-vis the small principalities: offer ‘new prospects’ under pressure of ‘haste’, not to mention threat.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

Menon met the Sheikh of Mangrol, a state of 42 villages under the suzeranity of Junagadh. Menon lured the Sheikh (ruler) of Mangrol, with promises of autonomy and control of villages even inside Junagadh, to accede to India on 20 September. However, the Sheikh withdrew his accession to India the very next day. According to scholar Rakesh Ankit this throws light on Menon's use of pressure and even threat in regards to small principalities.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 377 <nowiki>''</nowiki>More importantly, on his way back, Menon stopped at Rajkot where the Muslim (and not Hindu)47 Sheikh of Mangrol, a state of 42 villages half of which were under Junagadh’s jurisdiction, had been summoned to meet him. Menon lured the Sheikh with promises of autonomy and rights even in regard to the villages under Junagadh and prevailed upon him to sign an instrument of accession on 20 September. However, the Sheikh withdrew it the very next day in a telegram to the Regional Commissioner of Rajkot, which throws some light on Menon’s modus operandi vis-à-vis the small principalities: offer ‘new prospects’ under pressure of ‘haste’, not to mention threat.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

| ⚫ | On 20 September, Mountbatten asserted that Junagadh's accession to Pakistan was in violation of the principles of Partition and also claimed that Junagadh was making 'large-scale' military operations and causing its neighbours to become apprehensive. Thus, Mountbatten claimed that India would send ‘a small force as a very natural precautionary counter-measure’. However, to Junagadh the Indian forces did not appear to be a precautionary measure but as signs of an impending attack. Bhutto requested Pakistan for help.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 377</ref> Pakistan termed the buildup of the presence of Indian troops on Junagadh's borders a hostile act and an enroachment on Junagadh's sovereignty.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 377 <nowiki>''</nowiki> Jinnah sent a telegram to Mountbatten on 19 September and, pointing to the ‘large troop concentrations along the borders of Junagadh’, termed ‘any encroachment on Junagadh’s sovereignty or its territory…a hostile act’. In Delhi, the same day, Liaquat discussed Junagadh with Ismay<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

Babariawad, an area of 50 villages ruled by landowners, which was a feudatory of Junagadh declared itself independent of the latter and expressed a desire to accede to India. In light of these developments, Mountbatten, Nehru and Patel met with their military chiefs on 22 September where they decided to take no notice of the fact that the Sheikh of Mongrol had withdrawn his accession to India. Menon claimed that both Babariawad and Mangrol were free of Junagadh's jurisdiction. Nehru, however, wanted to be sure that Mangrol and Babariawad were not under Junagadh's jurisdiction and could accede to India independently of Junagadh before asking the Nawab to withdraw his forces from Babariawad.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 378 <nowiki>''</nowiki>On 22 September, Mountbatten, Nehru and Patel met with their military chiefs to decide the future course of action, given this new development. Before that, Menon reported on his visit, in particular on the Sheikh of Mangrol’s about-turn on accession. Unlike the understanding that ‘by the time this news of the Sheikh’s volte face reached Delhi his accession had already been accepted’, it was in this meeting that it was agreed upon deliberation that ‘no notice should be taken’ of the Sheikh’s withdrawal. On Babariawad, Menon’s ‘rough and ready’ assessment was that India’s position was ‘unassailable’ as with the lapse of British paramountcy, Babariawad’s erstwhile attachment to Junagadh had lapsed too. Menon termed it, like Mangrol, a ‘non-jurisdictional’ state, if at all, under Junagadh.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

Babariawad, an area of 50 villages ruled by landowners, which was a feudatory of Junagadh declared itself independent of the latter and expressed a desire to accede to India. In light of these developments, Mountbatten, Nehru and Patel met with their military chiefs on 22 September where they decided to take no notice of the fact that the Sheikh of Mongrol had withdrawn his accession to India. Menon claimed that both Babariawad and Mangrol were free of Junagadh's jurisdiction. Nehru, however, wanted to be sure that Mangrol and Babariawad were not under Junagadh's jurisdiction and could accede to India independently of Junagadh before asking the Nawab to withdraw his forces from Babariawad.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 378 <nowiki>''</nowiki>On 22 September, Mountbatten, Nehru and Patel met with their military chiefs to decide the future course of action, given this new development. Before that, Menon reported on his visit, in particular on the Sheikh of Mangrol’s about-turn on accession. Unlike the understanding that ‘by the time this news of the Sheikh’s volte face reached Delhi his accession had already been accepted’, it was in this meeting that it was agreed upon deliberation that ‘no notice should be taken’ of the Sheikh’s withdrawal. On Babariawad, Menon’s ‘rough and ready’ assessment was that India’s position was ‘unassailable’ as with the lapse of British paramountcy, Babariawad’s erstwhile attachment to Junagadh had lapsed too. Menon termed it, like Mangrol, a ‘non-jurisdictional’ state, if at all, under Junagadh.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

== Military plans == |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

At their meeting of 24 September Mountbatten, Nehru, Ismay, Patel and Menon decided to send troops to Mangrol even though Mangrol's ruler claimed to have acceded to India under duress.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 379-380</ref> |

|||

At the same time India, using Menon's reading, informed Pakistan of Mangrol's enforced accession to India. Pakistan's Prime Minister, Liaquat Ali Khan, declared both this and Babariawad's declaration of independence as 'invalid' and described the ‘attitude of the Indian States Department tantamount to invasion of Junagadh’ which was legally Pakistani territory.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 380 <nowiki>''</nowiki>Liaquat declared this, and Babariawad’s declaration of independence, ‘invalid’ and termed the ‘attitude of the Indian States Department tantamount to invasion of Junagadh’, which, after all, was a part of Pakistan.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

At the same time India, using Menon's reading, informed Pakistan of Mangrol's enforced accession to India. Pakistan's Prime Minister, Liaquat Ali Khan, declared both this and Babariawad's declaration of independence as 'invalid' and described the ‘attitude of the Indian States Department tantamount to invasion of Junagadh’ which was legally Pakistani territory.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 380 <nowiki>''</nowiki>Liaquat declared this, and Babariawad’s declaration of independence, ‘invalid’ and termed the ‘attitude of the Indian States Department tantamount to invasion of Junagadh’, which, after all, was a part of Pakistan.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

By late September India stepped up its publicity campaign and sent to London, Washington and New York a copy of the press communiqué in which it claimed that Junagadh's mostly non-Muslim residents were interested in India and that the state was geographically contiguous to Pakistan. In it India also accused Junagadh's Nawab of 'evasive' dealings and demanded that the matter be settled by a referendum.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 380</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | Meanwhile other military and political developments were taking place. The Indian Army's Bombay Area Commander sent a telegram to Indian Army Headquarters on 25 September reporting that 25 boxes of ammunition and 26,000 gallons of petrol arrived in Veraval from Karachi. He also claimed that Harvey-Jones, the European member of Junagadh executive council, had been issuing instructions to state forces in Babariawad and that Junagadh was strengthening its police force and raising a 'Home Guard' in its villages.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 380</ref> Buch also claimed that 'men of war' were arriving in Junagadh. However, it was later discovered in December 1947 that the 'Home Guard' contained only 617 men who did not even put up 'token resistance'. It was also claimed that personnel from Junagadh State Lancers were fighting Indian troops in Hyderabad. It was later revealed that this was a false claim.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 381 <nowiki>''</nowiki> Buch reported the ‘arrival of men of war [in Veraval] and departure of two European officers for Junagadh’. In December 1947, it would be seen that this much-vaunted Home Guard had all of 617 men with only 129 in Junagadh city and 122 each in Keshod, Kutiyana and elsewhere. They would not put up even a token resistance. Still later, in August 1948, it would be claimed that retired personnel of Junagadh State Lancers were in Hyderabad fighting against Indian troops, before D.S. Bakhle, Chief Civil Administrator of Hyderabad, set the record straight that ‘none were in any way connected with the Razakars or have come to adverse notice politically or otherwise’<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Also on 25 September, at the suggestion of Menon and with the sponsorship of the All India States Peoples’ Conference’s Praja Mandal movement and with the support of the Bombay-based 'Gujarat States Organisation’, led by the Maharaja of Lunawada, a provisional government for Junagadh was formed in Bombay on 25 September. This self-styled government was led by Mahatma Gandhi's nephew, Samaldas Gandhi. Menon played an important role in forming this provisional government.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 381 <nowiki>''</nowiki>Suggested by Menon and sponsored by the All India States Peoples’ Conference’s Praja Mandal movement, this self-styled government led by Samaldas Gandhi, a nephew of the Mahatma, was seeking to move to Rajkot and other pockets of Junagadh territory on the outskirts. It was supported by a ‘Gujarat States Organisation’, led by the Maharaja of Lunawada, which too was based in Bombay<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Meanwhile, the military chiefs were concerned of an impending clash between Indian forces and the forces of Junagadh and were also concerned by other practical constraints and instead recommended a settlement by negotiations instead of a military solution. Nehru was upset with this.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 382</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Mountbatten favoured ‘any method, reference to some impartial tribunal, which could settle Mangrol and Babariawad’s accession to India before Indian troops went in’. Patel opposed this because ‘we accepted accession of Mangrol without being quite sure as to the correct status of Mangrol’.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 383 <nowiki>''</nowiki>Patel baulked at arbitration because, as he put it, one of its implication would be that ‘we accepted accession of Mangrol without being quite sure as to the correct status of Mangrol’.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

Nehru layed out India's position. This position was that India did not accept Junagadh's accession to Pakistan, disagreed on the constitutional position of Mangrol and Babariawad and therefore wanted Junagadh to withdraw its forces from these two areas. As it would be unlikely that Junagadh would withdraw its forces from there, India would send its own troops there. Nehru did not favour going to war and invited Pakistan to allow a referendum under impartial auspices in Junagadh.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 383</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | The provisional government upped the ante 'considerably' and decided that a tank company would be sent to neighbouring Porbandar even though it was doubtful whether any part of Porbandar was contiguous to the disputed Mangrol. India also agreed to allowing the provisional government to take over administration of the state's outlying pockets. The provisional government's Defence Committee discussed a concrete military plan.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 384 <nowiki>''</nowiki>The provisional Defence Committee in its first meeting did not merely direct ‘the military chiefs to plan accordingly’, but, upping the ante considerably, decided that a tank company was to proceed to the neighbouring Porbandar even though there was doubt whether any part of Porbandar was contiguous to the disputed Mangrol. Further, it authorised aerial reconnaissance of Junagadh troops and ordered that their movements across the territory of states that had acceded to India be stopped. Finally, New Delhi agreed to the provisional government taking over administration in the outlying pockets of the state. Nehru was asked to intimate the above, barring the last, to Liaquat. The Defence Committee decided to meet again to discuss concrete military plans on, ironically, 2 October 1947—Gandhi’s birthday<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | After obtaining a pro-India legal opinion from Moonckton concerning the disputed Mangrol and Babariawad, Nehru met Liaquat Ali Khan on 1 October and requested him to get Junagadh to withdraw its troops from Babariawad. Liaquat Ali Khan did not give any commitment to this although he indicated a 'probable' withdrawal. To his Cainet, Nehru proclaimed ‘India had to take some action to honour its commitments [but] it was necessary at the same time to do everything to avoid war’. On the next day tensions escalated instead of easing. Apparently Junagadh had mobilised its troops to Mangrol. Nehru termed this a s a 'further act of aggression' and warned Liaquat that Indian troops would be moving to the neighbouring Porbandar.<ref name=":2">Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 384</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

As tensions escalated the CoS asked the Cabinet to approve a despatchment of forces to Kathiawar under Brigadier Gurdial Singh. There were two military objectives: (i) ‘to assure those states in Kathiawar which have acceded to India that [it] is prepared to protect them from aggression’ and (ii) ‘to be prepared to take action to protect the subjects of Mangrol and Babariawad and other states in Junagadh territory as well as the non-Muslim subjects of Junagadh’. At the same time the forces would stop short of entering either Junagadh or Mangrol/Babariawad as Pakistan could regard that as an act of war.<ref name=":3">Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 384-385</ref> |

As tensions escalated the CoS asked the Cabinet to approve a despatchment of forces to Kathiawar under Brigadier Gurdial Singh. There were two military objectives: (i) ‘to assure those states in Kathiawar which have acceded to India that [it] is prepared to protect them from aggression’ and (ii) ‘to be prepared to take action to protect the subjects of Mangrol and Babariawad and other states in Junagadh territory as well as the non-Muslim subjects of Junagadh’. At the same time the forces would stop short of entering either Junagadh or Mangrol/Babariawad as Pakistan could regard that as an act of war.<ref name=":3">Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 384-385</ref> |

||

| Line 90: | Line 68: | ||

As military plans were being discussed Lockhart and Hall reminded the Committee that Porbandar and Mangrol were not contiguous, despite Patel and Menon opposing this stance. Mountbatten proposed to deal with this by using landing craft tanks to carry troops.<ref name=":6" /> |

As military plans were being discussed Lockhart and Hall reminded the Committee that Porbandar and Mangrol were not contiguous, despite Patel and Menon opposing this stance. Mountbatten proposed to deal with this by using landing craft tanks to carry troops.<ref name=":6" /> |

||

== Provisional Government == |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Also on 25 September, at the suggestion of Menon and with the sponsorship of the All India States Peoples’ Conference’s Praja Mandal movement and with the support of the Bombay-based 'Gujarat States Organisation’, led by the Maharaja of Lunawada, a provisional government for Junagadh was formed in Bombay on 25 September. This self-styled government was led by Mahatma Gandhi's nephew, Samaldas Gandhi. Menon played an important role in forming this provisional government.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 381 <nowiki>''</nowiki>Suggested by Menon and sponsored by the All India States Peoples’ Conference’s Praja Mandal movement, this self-styled government led by Samaldas Gandhi, a nephew of the Mahatma, was seeking to move to Rajkot and other pockets of Junagadh territory on the outskirts. It was supported by a ‘Gujarat States Organisation’, led by the Maharaja of Lunawada, which too was based in Bombay<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Meanwhile, the military chiefs were concerned of an impending clash between Indian forces and the forces of Junagadh and were also concerned by other practical constraints and instead recommended a settlement by negotiations instead of a military solution. Nehru was upset with this.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 382</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | While India was ‘forcing the pace’, Pakistan was seeking diplomatic ammunition. On 22 October, Pakistan’s High Commissioner in India approached his British counterpart and asked to be allowed to inspect the former Political Department’s records concerning Junagadh’s relations with Mangrol. The British High Commissioner thought it better to express ‘regret’ that the requested records could not be made available.<ref name=":7" /> |

||

| ⚫ | Mountbatten favoured ‘any method, reference to some impartial tribunal, which could settle Mangrol and Babariawad’s accession to India before Indian troops went in’. Patel opposed this because ‘we accepted accession of Mangrol without being quite sure as to the correct status of Mangrol’.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 383 <nowiki>''</nowiki>Patel baulked at arbitration because, as he put it, one of its implication would be that ‘we accepted accession of Mangrol without being quite sure as to the correct status of Mangrol’.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

| ⚫ | The provisional government upped the ante 'considerably' and decided that a tank company would be sent to neighbouring Porbandar even though it was doubtful whether any part of Porbandar was contiguous to the disputed Mangrol. India also agreed to allowing the provisional government to take over administration of the state's outlying pockets. The provisional government's Defence Committee discussed a concrete military plan.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 384 <nowiki>''</nowiki>The provisional Defence Committee in its first meeting did not merely direct ‘the military chiefs to plan accordingly’, but, upping the ante considerably, decided that a tank company was to proceed to the neighbouring Porbandar even though there was doubt whether any part of Porbandar was contiguous to the disputed Mangrol. Further, it authorised aerial reconnaissance of Junagadh troops and ordered that their movements across the territory of states that had acceded to India be stopped. Finally, New Delhi agreed to the provisional government taking over administration in the outlying pockets of the state. Nehru was asked to intimate the above, barring the last, to Liaquat. The Defence Committee decided to meet again to discuss concrete military plans on, ironically, 2 October 1947—Gandhi’s birthday<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

| ⚫ | After obtaining a pro-India legal opinion from Moonckton concerning the disputed Mangrol and Babariawad, Nehru met Liaquat Ali Khan on 1 October and requested him to get Junagadh to withdraw its troops from Babariawad. Liaquat Ali Khan did not give any commitment to this although he indicated a 'probable' withdrawal. To his Cainet, Nehru proclaimed ‘India had to take some action to honour its commitments [but] it was necessary at the same time to do everything to avoid war’. On the next day tensions escalated instead of easing. Apparently Junagadh had mobilised its troops to Mangrol. Nehru termed this a s a 'further act of aggression' and warned Liaquat that Indian troops would be moving to the neighbouring Porbandar.<ref name=":2">Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 384</ref> |

||

== Allegations of Junagadh's military plans == |

|||

Nawanagar contributed three companies, Porbandar and Bhavnagar both contributed one company each and Baroda also contributed men and the establishment of a direct chain of command between New Delhi and Kathiawar Defence Force was considered. All this was to combat Junagadh’s total force of 1,500 men.<ref name=":8">Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 390</ref> |

Nawanagar contributed three companies, Porbandar and Bhavnagar both contributed one company each and Baroda also contributed men and the establishment of a direct chain of command between New Delhi and Kathiawar Defence Force was considered. All this was to combat Junagadh’s total force of 1,500 men.<ref name=":8">Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 390</ref> |

||

| Line 100: | Line 86: | ||

Meanwhile, Pakistan communicated to India that it had no problem with Menon coming to Lahore to discuss at the secretary level about a plebiscite in Junagadh and all other states. However, the Committee decided that ‘it would be a waste of time for him to go as no decisions could be reached on that level’. Instead, it gave ‘a go-ahead’ order to Brigadier Gurdial Singh and Regional Commissioner N.M. Buch on 25 October.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 390-391 <nowiki>''</nowiki>Meanwhile, word had been received from Karachi that it had no objection to Menon visiting Lahore for discussions at the secretary level about plebiscite in not just Junagadh but ‘any state or all states’.The Committee decided that ‘it would be a waste of time for him to go as no decisions could be reached on that level’. Instead, on 25 October, a go-ahead order was given to Brigadier Gurdial Singh and Regional Commissioner N.M. Buch.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

Meanwhile, Pakistan communicated to India that it had no problem with Menon coming to Lahore to discuss at the secretary level about a plebiscite in Junagadh and all other states. However, the Committee decided that ‘it would be a waste of time for him to go as no decisions could be reached on that level’. Instead, it gave ‘a go-ahead’ order to Brigadier Gurdial Singh and Regional Commissioner N.M. Buch on 25 October.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 390-391 <nowiki>''</nowiki>Meanwhile, word had been received from Karachi that it had no objection to Menon visiting Lahore for discussions at the secretary level about plebiscite in not just Junagadh but ‘any state or all states’.The Committee decided that ‘it would be a waste of time for him to go as no decisions could be reached on that level’. Instead, on 25 October, a go-ahead order was given to Brigadier Gurdial Singh and Regional Commissioner N.M. Buch.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

| ⚫ | According to scholar Rakesh Ankit the details of this report revealed the farce of India’s elaborate preparations. Junagadh had less than 5,000 personnel, less than 4,200 guns of various kinds and less than 400 boxes of ammunition for those guns. Junagadh produced seven cartridges a day and had sixty countrymade canons, half of them being non-serviceable. It was this undersized army which Mountbatten, Patel and Menon had accused of making ‘large-scale military preparations threatening the neighbouring states’.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 394 <nowiki>''</nowiki>It makes for a tragic reading and renders farce New Delhi’s elaborate preparations. Junagadh had less than 5,000 personnel in their various forces, less than 4,200 guns of all types and less than 400 boxes of ammunition for these guns. The state produced seven cartridges a day and had 60 countrymade canons, half of which were not serviceable. Even after taking into account the six Pakistan army officers who were alleged to be helping the state troops in organising the defence of the city, four Pakistan navy officers and P.C. Hailey, the European ex-political agent managing the state’s finances, it was this puny army that had been held to be making ‘large-scale military preparations threatening the neighbouring states’ by Mountbatten, Patel and Menon.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | India’s heavy-handed actions caused resentment among Junagadh’s personnel and arms were reportedly distributed among Junagadh’s Muslim population.<ref name=":11">Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 394</ref> |

||

== Indian response and military plans == |

|||

| ⚫ | In a meeting on 24 September, Hall confirmed that by 30 September India's navy would be ready in Bombay although Roy Bucher asserted that action would not be possible in Junagadh for 18 days. Bucher proposed that Junagadh be warned by positioning Indian troops alongside its railway lines. Mountbatten was doubtful of how effective this plan would be.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 380</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Meanwhile other military and political developments were taking place. The Indian Army's Bombay Area Commander sent a telegram to Indian Army Headquarters on 25 September reporting that 25 boxes of ammunition and 26,000 gallons of petrol arrived in Veraval from Karachi. He also claimed that Harvey-Jones, the European member of Junagadh executive council, had been issuing instructions to state forces in Babariawad and that Junagadh was strengthening its police force and raising a 'Home Guard' in its villages.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 380</ref> Buch also claimed that 'men of war' were arriving in Junagadh. However, it was later discovered in December 1947 that the 'Home Guard' contained only 617 men who did not even put up 'token resistance'. It was also claimed that personnel from Junagadh State Lancers were fighting Indian troops in Hyderabad. It was later revealed that this was a false claim.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 381 <nowiki>''</nowiki> Buch reported the ‘arrival of men of war [in Veraval] and departure of two European officers for Junagadh’. In December 1947, it would be seen that this much-vaunted Home Guard had all of 617 men with only 129 in Junagadh city and 122 each in Keshod, Kutiyana and elsewhere. They would not put up even a token resistance. Still later, in August 1948, it would be claimed that retired personnel of Junagadh State Lancers were in Hyderabad fighting against Indian troops, before D.S. Bakhle, Chief Civil Administrator of Hyderabad, set the record straight that ‘none were in any way connected with the Razakars or have come to adverse notice politically or otherwise’<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | While India was ‘forcing the pace’, Pakistan was seeking diplomatic ammunition. On 22 October, Pakistan’s High Commissioner in India approached his British counterpart and asked to be allowed to inspect the former Political Department’s records concerning Junagadh’s relations with Mangrol. The British High Commissioner thought it better to express ‘regret’ that the requested records could not be made available.<ref name=":7">Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 389</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

By the time the Defence Committee held its tenth meeting on 28 October the crisis in Kashmir had overshadowed Junagadh. The events in Junagadh became part of the wider context of affairs in relation to Kashmir.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 391 <nowiki>''</nowiki>Junagadh now assumed ‘relation to the wider context of events in Kashmir<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

By the time the Defence Committee held its tenth meeting on 28 October the crisis in Kashmir had overshadowed Junagadh. The events in Junagadh became part of the wider context of affairs in relation to Kashmir.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 391 <nowiki>''</nowiki>Junagadh now assumed ‘relation to the wider context of events in Kashmir<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

| Line 107: | Line 106: | ||

After discussions on how military action in Junagadh and Kashmir would effect each other, the Committee agreed that the proposed military action in Junagadh would go ahead on 1 November if Pakistan did not agree to a plebiscite in Junagadh. Mountbatten also unsuccessfully attempted to convince Nehru and Patel to use the Central Reserve Police Force instead of the Army in Junagadh, in view of the Kashmir situation. Patel rejected this proposal. At the same time Patel also did not object to Mountbatten to informing Jinnah about India’s intended action as this would prevent India from being accused of bad faith.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 393</ref> |

After discussions on how military action in Junagadh and Kashmir would effect each other, the Committee agreed that the proposed military action in Junagadh would go ahead on 1 November if Pakistan did not agree to a plebiscite in Junagadh. Mountbatten also unsuccessfully attempted to convince Nehru and Patel to use the Central Reserve Police Force instead of the Army in Junagadh, in view of the Kashmir situation. Patel rejected this proposal. At the same time Patel also did not object to Mountbatten to informing Jinnah about India’s intended action as this would prevent India from being accused of bad faith.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 393</ref> |

||

== Jinnah-Mountbatten Meeting == |

|||

As Mountbatten went to Lahore to salvage the situation in Kashmir and Junagadh the Indian military was already in motion. Pre-empting the Jinnah-Mountbatten meeting, Indian troops entered Babariawad at Nagasari on 1 November at 6:30 am. The Indian military disarmed the local police and took over the administration. They also noted that Junagadh town firmed up its defences.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 393 <nowiki>''</nowiki>pre-empting the Mountbatten– Jinnah meeting, Indian troops entered the territory of Babariawad at Nagasari on 1 November at 6:30 am and, disarming the local police, took over the administration.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

As Mountbatten went to Lahore to salvage the situation in Kashmir and Junagadh the Indian military was already in motion. Pre-empting the Jinnah-Mountbatten meeting, Indian troops entered Babariawad at Nagasari on 1 November at 6:30 am. The Indian military disarmed the local police and took over the administration. They also noted that Junagadh town firmed up its defences.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 393 <nowiki>''</nowiki>pre-empting the Mountbatten– Jinnah meeting, Indian troops entered the territory of Babariawad at Nagasari on 1 November at 6:30 am and, disarming the local police, took over the administration.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

| Line 113: | Line 113: | ||

Upon being informed by Mountbatten that Indian troops had entered Babariawad that same day Jinnah protested that India had not asked for Pakistan’s co-operation before carrying out the operation.<ref name=":9" /> |

Upon being informed by Mountbatten that Indian troops had entered Babariawad that same day Jinnah protested that India had not asked for Pakistan’s co-operation before carrying out the operation.<ref name=":9" /> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

Meanwhile, the Indian military’s operation in Mangrol did not go smoothly contrary to India’s claims. The Sheikh was proving ‘unhelpful’ and the Muslim population ‘unfriendly and suspicious’.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 393 <nowiki>''</nowiki> The operation in Mangrol was not as smooth as was projected then and accepted since. The summary report of 2 November confirmed troops’ entrance into Mangrol where the Sheikh was proving ‘unhelpful’ and the Muslim population ‘very unfriendly and suspicious’<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> Junagadh city fort was garrisoned and Keshod airport saw hectic civilian activity.<ref name=":9" /> |

Meanwhile, the Indian military’s operation in Mangrol did not go smoothly contrary to India’s claims. The Sheikh was proving ‘unhelpful’ and the Muslim population ‘unfriendly and suspicious’.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 393 <nowiki>''</nowiki> The operation in Mangrol was not as smooth as was projected then and accepted since. The summary report of 2 November confirmed troops’ entrance into Mangrol where the Sheikh was proving ‘unhelpful’ and the Muslim population ‘very unfriendly and suspicious’<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> Junagadh city fort was garrisoned and Keshod airport saw hectic civilian activity.<ref name=":9" /> |

||

| Line 118: | Line 119: | ||

Once these two areas were occupied, Junagadh forces withdrew to within a 10 mile radius from the main city. Indian troops prepared themselves for their final push a report was sent on 5 November detailing the state of the Junagadh forces.<ref name=":10" /> |

Once these two areas were occupied, Junagadh forces withdrew to within a 10 mile radius from the main city. Indian troops prepared themselves for their final push a report was sent on 5 November detailing the state of the Junagadh forces.<ref name=":10" /> |

||

| ⚫ | According to scholar Rakesh Ankit the details of this report revealed the farce of India’s elaborate preparations. Junagadh had less than 5,000 personnel, less than 4,200 guns of various kinds and less than 400 boxes of ammunition for those guns. Junagadh produced seven cartridges a day and had sixty countrymade canons, half of them being non-serviceable. It was this undersized army which Mountbatten, Patel and Menon had accused of making ‘large-scale military preparations threatening the neighbouring states’.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 394 <nowiki>''</nowiki>It makes for a tragic reading and renders farce New Delhi’s elaborate preparations. Junagadh had less than 5,000 personnel in their various forces, less than 4,200 guns of all types and less than 400 boxes of ammunition for these guns. The state produced seven cartridges a day and had 60 countrymade canons, half of which were not serviceable. Even after taking into account the six Pakistan army officers who were alleged to be helping the state troops in organising the defence of the city, four Pakistan navy officers and P.C. Hailey, the European ex-political agent managing the state’s finances, it was this puny army that had been held to be making ‘large-scale military preparations threatening the neighbouring states’ by Mountbatten, Patel and Menon.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

India’s heavy-handed actions caused resentment among Junagadh’s personnel and arms were reportedly distributed among Junagadh’s Muslim population.<ref name=":11">Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 394</ref> |

|||

On 7 November, Indian forces decided to prepare for a final push into Junagadh after the post and telegraph installations at Kutiyana were threatened. However, over 8-9 November the invasion of Junagadh turned into an ‘invitation’ to Junagadh. On 9 November, Bhutto communicated to Mountbatten on 9 November his request to Buch ‘to assist Junagadh in preservation of law and order without prejudice to honourable understanding that may be arrived at by all concerned’. The Government of India took over the administration of Junagadh on 9 November.<ref name=":11" /> |

On 7 November, Indian forces decided to prepare for a final push into Junagadh after the post and telegraph installations at Kutiyana were threatened. However, over 8-9 November the invasion of Junagadh turned into an ‘invitation’ to Junagadh. On 9 November, Bhutto communicated to Mountbatten on 9 November his request to Buch ‘to assist Junagadh in preservation of law and order without prejudice to honourable understanding that may be arrived at by all concerned’. The Government of India took over the administration of Junagadh on 9 November.<ref name=":11" /> |

||

== Developments after entry of Indian troops == |

|||

India’s Ministry of Law made it clear that Junagadh’s accession to Pakistan had not been nullified by referendum and that Junagadh had not acceded to India yet. But India went ahead with the referendum because it believed the result would be in its favour.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 395 <nowiki>''</nowiki>A note by Ministry of Law made it clear that Junagadh’s accession to Pakistan had not been nullified by referendum and the state had not acceded to India yet. However, New Delhi went ahead because ‘it was almost likely that the referendum will be in our favour’.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

India’s Ministry of Law made it clear that Junagadh’s accession to Pakistan had not been nullified by referendum and that Junagadh had not acceded to India yet. But India went ahead with the referendum because it believed the result would be in its favour.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 395 <nowiki>''</nowiki>A note by Ministry of Law made it clear that Junagadh’s accession to Pakistan had not been nullified by referendum and the state had not acceded to India yet. However, New Delhi went ahead because ‘it was almost likely that the referendum will be in our favour’.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

| Line 131: | Line 129: | ||

Reports arrived of widespread murder, rape and looting of Muslims in Junagadh following the arrival of Indian troops.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 397 <nowiki>''</nowiki>A group of Muslims from Junagadh represented the second type of voices in protest and far more important than Owen because their account puts an unflattering light on the secular claims of the early Indian state. They wrote to Mountbatten and Nehru on 30 November 1947 complaining about the loot, plunder, rape and murder in the state especially at Kutiyana following the entrance of the Indian troops notwithstanding the assurances given by Patel in his visit to Junagadh.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> Many Muslims from Junagadh began migrating to Pakistan.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 396 <nowiki>''</nowiki>Daily reports from 12 to 25 January 1948 confirm that Muslim families were leaving Junagadh in considerable numbers with most embarking from Veraval for Karachi.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

Reports arrived of widespread murder, rape and looting of Muslims in Junagadh following the arrival of Indian troops.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 397 <nowiki>''</nowiki>A group of Muslims from Junagadh represented the second type of voices in protest and far more important than Owen because their account puts an unflattering light on the secular claims of the early Indian state. They wrote to Mountbatten and Nehru on 30 November 1947 complaining about the loot, plunder, rape and murder in the state especially at Kutiyana following the entrance of the Indian troops notwithstanding the assurances given by Patel in his visit to Junagadh.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> Many Muslims from Junagadh began migrating to Pakistan.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 396 <nowiki>''</nowiki>Daily reports from 12 to 25 January 1948 confirm that Muslim families were leaving Junagadh in considerable numbers with most embarking from Veraval for Karachi.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

== |

== Positions of India and Pakistan at the United Nations == |

||

On 15 January 1948 India and Pakistan sparred over a number of issues at the UN Security Council including the ‘invasion’ in Junagadh.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 400</ref> |

On 15 January 1948 India and Pakistan sparred over a number of issues at the UN Security Council including the ‘invasion’ in Junagadh.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 400</ref> |

||

| Line 137: | Line 135: | ||

In early February, India did mention Mangrol and stressed its ‘separate status’ and the Sheikh’s signing of accession but did not mention that Mangrol later withdrew its accession. India also wrongly claimed that Junagadh was taken without firing a shot.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 401 <nowiki>''</nowiki> He insisted again that Junagadh was taken without firing a shot; not quite true.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

In early February, India did mention Mangrol and stressed its ‘separate status’ and the Sheikh’s signing of accession but did not mention that Mangrol later withdrew its accession. India also wrongly claimed that Junagadh was taken without firing a shot.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 401 <nowiki>''</nowiki> He insisted again that Junagadh was taken without firing a shot; not quite true.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

| ⚫ | Nehru also shifted from his earlier position of allowing a plebiscite under the UN and now said that it was unnecessary for a plebiscite to be held under the UN though it could send one or two observers if it wished to do so. However, India also made it clear that it would not under any circumstances postpone the plebiscite so as to allow the UN or Pakistan to send observers.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 401 <nowiki>''</nowiki>In yet another shift from his earlier position, Nehru now felt it ‘quite unnecessary to hold the plebiscite under the authority of the UN but if the UN thinks it desirable, it may send one or two observers’. Under no circumstances, however, would India agree to the postponement of the plebiscite to enable UN and Pakistan to send their observers.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

On 18 February 1948, Pakistan called India’s invasion of Junagadh and the proposed plebiscite a ‘fait accompli’ and called upon the Security Council to ask India to withdraw its forces and restore the Nawab to power and then conduct a plebiscite under UN auspices.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 401</ref> |

On 18 February 1948, Pakistan called India’s invasion of Junagadh and the proposed plebiscite a ‘fait accompli’ and called upon the Security Council to ask India to withdraw its forces and restore the Nawab to power and then conduct a plebiscite under UN auspices.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 401</ref> |

||

| Line 145: | Line 141: | ||

==Plebiscite== |

==Plebiscite== |

||

| ⚫ | Nehru also shifted from his earlier position of allowing a plebiscite under the UN and now said that it was unnecessary for a plebiscite to be held under the UN though it could send one or two observers if it wished to do so. However, India also made it clear that it would not under any circumstances postpone the plebiscite so as to allow the UN or Pakistan to send observers.<ref>Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 401 <nowiki>''</nowiki>In yet another shift from his earlier position, Nehru now felt it ‘quite unnecessary to hold the plebiscite under the authority of the UN but if the UN thinks it desirable, it may send one or two observers’. Under no circumstances, however, would India agree to the postponement of the plebiscite to enable UN and Pakistan to send their observers.<nowiki>''</nowiki></ref> |

||

Douglas Brown of the Daily Telegraph as well as Pakistani newspaper Dawn expressed concerns about the propriety of the plebiscite’s arrangement. On 26 February, Pakistan termed India’s proceeding with the plebiscite a ‘discourtesy to Pakistan and the Security Council’. After the last few proceedings, the UN’s focus shifted completely to Kashmir.<ref name=":12">Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 402</ref> |

Douglas Brown of the Daily Telegraph as well as Pakistani newspaper Dawn expressed concerns about the propriety of the plebiscite’s arrangement. On 26 February, Pakistan termed India’s proceeding with the plebiscite a ‘discourtesy to Pakistan and the Security Council’. After the last few proceedings, the UN’s focus shifted completely to Kashmir.<ref name=":12">Ankit, Rakesh. "The accession of Junagadh, 1947–48: Colonial sovereignty, state violence and post-independence India." ''The Indian Economic and Social History Review'', 53, 3 (2016): 402</ref> |

||

Revision as of 08:25, 5 July 2017

Junagadh was one of the princely states of India. Its mostly Hindu population of eighty percent was ruled by a Muslim Nawab (ruler). The state bordered India but his state to Pakistan had sea links with the Muslim state of Pakistan. A mirror image of Kashmir, its Muslim ruler acceded to Pakistan in spite of his Hindu subjects' wishes at the guidance of his pro-Pakistan chief minister Sir Shahnawaz Bhutto.[1]

India did not accept the accession, blockaded Junagadh and then invaded it. India imposed a plebiscite and gained its desired result, making Junagadh its part after a vote in its favour.[1] In the words of scholar Rakesh Ankit the Indian state's action in Junagadh was just another instance of India using force to incorporate princely states and Indian Muslims into India.[2]

India took liberties with facts and laws on at least three occasions in Junagadh’s case. The question of Mangrol’s accession to India provided Patel and Menon with the ‘thin end of the wedge’ to pressurise Junagadh as India meted out ‘rough’ treatment on Junagadh’s sub-states.[3] The second instance was India’s alarmist claims about Junagadh’s military capability and help it received from Pakistan.[4] The third instance was the way India carried out the plebiscite in Junagadh as it acted as the judge, jury and executioner of the entire case.[5]

Background

The statements of the Diwan of Junagadh, Khan Bahadur Abdul Qadir, in April and May and Nabi Buksh, advisor of Junagadh's ruler, Nawab Mahabat Khan, were interpreted by Mountbatten as a sign that Junagadh intended to accede to India. However, a group of Muslim League politicians from neighbouring Sindh, led by Sir Shah Nawaz Bhutto, soon joined Junagadh's executive council and Bhutto replaced Qadir as Diwan.[6]

On 12 July the Nawab relayed to Muhammad Ali Jinnah that he wished to join his state with Pakistan and he sent his Private Secretary Ismail Abrahani to Karachi to negotiate accession terms. This development surprised India's Ministry of States and its minister-in-charge Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. Patel communicated to Bhutto that the Hindu population's desire and the decision of the ‘majority of states and talukas’ in Kathiawar to join India could not be ignored.[6]

Junagadh, by the end of August 1947, was repeatedly demanding that Pakistan accept its accession and its nervousness was increased by India's actions such as the Indian Navy patrolling Junagadh's port Veraval. At the request of India's Defence Minister Baldev Singh and the Ministry of States ‘to take such action as was possible [to stop] the possibility of ammunition being landed in Junagadh [from Pakistan]’ this order had been passed by India's naval chief, Rear-Admiral J.T.S. Hall, on 28 August 1947.[7]

Hall, however, was reluctant to do this and pointed out that it was ‘perfectly legitimate’ for Junagadh, in accordance with Commonwealth Conventions, International Maritime Laws and Joint Defence Council agreements, to import arms from Pakistan and ‘the only circumstances in which such importation could be checked [was] if the arms were exported from India or carried in a ship on the Indian register.[7]

When Hall expressed this concern to V.P. Menon, Secretary at the Ministry of States, Menon dismissed these reservations. He responded to Hall, indicating India's feelings on Junagadh:[7]

Junagadh is a state which proposes to accede to Pakistan...Import into Junagadh of large quantities of arms without the knowledge of [New Delhi] will be a direct threat to the...whole Kathiawar...We may justifiably claim that the question of self-preservation is involved in the proper restriction of arms traffic between Junagadh and foreign countries. On the question of how best to take preventive action, I would only emphasise that our measures should not be half-hearted.

It took Pakistan a month to accept Junagadh's accession. By 15 August, Junagadh's transport and communication links had come under Indian hands.[7]

Gopalaswami Ayyangar and Mountbatten agreed that Junagadh's accession to Pakistan was legally correct but Sardar Patel demanded that the decision of accession be in the hands of the people instead of the ruler.[8] Nehru layed out India's position. This position was that India did not accept Junagadh's accession to Pakistan, disagreed on the constitutional position of Mangrol and Babariawad and therefore wanted Junagadh to withdraw its forces from these two areas. As it would be unlikely that Junagadh would withdraw its forces from there, India would send its own troops there. Nehru did not favour going to war and invited Pakistan to allow a referendum under impartial auspices in Junagadh.[9]

On 20 September, Mountbatten asserted that Junagadh's accession to Pakistan was in violation of the principles of Partition and also claimed that Junagadh was making 'large-scale' military operations and causing its neighbours to become apprehensive. Thus, Mountbatten claimed that India would send ‘a small force as a very natural precautionary counter-measure’. However, to Junagadh the Indian forces did not appear to be a precautionary measure but as signs of an impending attack. Bhutto requested Pakistan for help.[10] Pakistan termed the buildup of the presence of Indian troops on Junagadh's borders a hostile act and an enroachment on Junagadh's sovereignty.[11]

At their meeting on 24 September, legal adviser Monckton told Mountbatten that since Junagadh had signed an instrument of accession to Pakistan there was no military way of changing this and Pakistan's consent would need to be obtained for any plebiscite India wished to conduct in Junagadh.[12]

Mangrol and Babariawad

Menon met the Sheikh of Mangrol, a state of 42 villages under the suzeranity of Junagadh. Menon lured the Sheikh (ruler) of Mangrol, with promises of autonomy and control of villages even inside Junagadh, to accede to India on 20 September. However, the Sheikh withdrew his accession to India the very next day. According to scholar Rakesh Ankit this throws light on Menon's use of pressure and even threat in regards to small principalities.[13]

Babariawad, an area of 50 villages ruled by landowners, which was a feudatory of Junagadh declared itself independent of the latter and expressed a desire to accede to India. In light of these developments, Mountbatten, Nehru and Patel met with their military chiefs on 22 September where they decided to take no notice of the fact that the Sheikh of Mongrol had withdrawn his accession to India. Menon claimed that both Babariawad and Mangrol were free of Junagadh's jurisdiction. Nehru, however, wanted to be sure that Mangrol and Babariawad were not under Junagadh's jurisdiction and could accede to India independently of Junagadh before asking the Nawab to withdraw his forces from Babariawad.[14]

By late September, the Sheikh of Mangrol refused to come to Rajkot to re-negotiate accession.[15]

At their meeting of 24 September Mountbatten, Nehru, Ismay, Patel and Menon decided to send troops to Mangrol even though Mangrol's ruler claimed to have acceded to India under duress.[16]

At the same time India, using Menon's reading, informed Pakistan of Mangrol's enforced accession to India. Pakistan's Prime Minister, Liaquat Ali Khan, declared both this and Babariawad's declaration of independence as 'invalid' and described the ‘attitude of the Indian States Department tantamount to invasion of Junagadh’ which was legally Pakistani territory.[17]

As tensions escalated the CoS asked the Cabinet to approve a despatchment of forces to Kathiawar under Brigadier Gurdial Singh. There were two military objectives: (i) ‘to assure those states in Kathiawar which have acceded to India that [it] is prepared to protect them from aggression’ and (ii) ‘to be prepared to take action to protect the subjects of Mangrol and Babariawad and other states in Junagadh territory as well as the non-Muslim subjects of Junagadh’. At the same time the forces would stop short of entering either Junagadh or Mangrol/Babariawad as Pakistan could regard that as an act of war.[18]

Nehru justified this on the grounds that he had made it clear to Liaquat Ali Khan that if Junagadh did not withdraw its troops from Babariawad and Mangrol, then Indian troops would move to Porbandar. This caused Bhutto to desperately request Pakistan for help.[18]

On 4 October, the Defence Committee explored the CoS' proposal. A major impediment in the discussion was the question of whether Porbandar and Mangrol were contiguous. While Menon insisted they were the CoS claimed that they were not and were 6 miles apart. It was also decided in the meeting that the provisional government would neither be given recognition nor interfered with.[18]

On 5 October, Nehru wrote to Liaquat Ali Khan and said that the setting up of the provisional government was ‘a spontaneous expression of popular resentment against Junagadh’s accession'. However, Nehru did not mention Menon's role in forming the provisional government.[18]

Nehru also termed the entry of Junagadh's forces in Mangrol as ‘a unilateral act of aggression’ and asked Liaquat to restore the ‘status quo preceding Junagadh’s accession to Pakistan’ as the ‘only basis for friendly negotiations’ which would result in the holding of a referendum.[18]

Liaquat Ali Khan responded that if independent legal opinion was taken on the status of Mangrol and Babariawad amd if India did not send any troops to either Junagadh, Mangrol or Babariawad then he would be prepared to request Junagadh to withdraw troops from Babariawad and not send troops to Mangrol.[18] Nehru welcomed Liaquat's proposals on Mangrol and Babariawad but also said that these two areas were not the main issue. Nehru said that there needed to be an agreement on Junagadh first. Pakistan responded and protested against India's 'indifference' to the activities of the provisional government of Junagadh.[19]

By 7 October, Indian troops stepped onto Porbandar. Even as differences remained between the Ministry of States and militay authorities over whether Porbandar was contiguous to Mangrol, Indian naval ships started making rounds between Bombay and Porbandar over the next ten days. By 15 October the Indian Army had 'signalled the endgame for Junagadh'. Its new objectives were to prevent Junagadh's administration from functioning in Babariawad and the Sheikh from functioning in Mangrol and to enable the Government of India to establish an interim administation in these areas that would conduct a plebiscite immediately. Their plan was to enter Babariawad and Mangrol by 1 November 1947 at the latest. [19]

The plan ignored the Sheikh of Mangrol's confirmation that there were no Junagadh troops in Mangrol, relayed by a telegram from Karachi.[20] When Nehru was informed that Junagadh's troops had crossed into the territory of another state which had already acceded to India, Jetpur, he considered it an act of aggression and 'deliberate flouting of [Indian] proposals’. Nehru communicated to Liaquat that his silence over the past fortnight and the further incursions by Junagadh had made India conclude that Pakistan did not want an amicable settlement.[19]

However, Nehru's claim about Pakistani silence was not quite true[21] as Liaquat actually had responded to Nehru's message and had sent him a letter on 6–7 October. At his meeting on 16 October with Mountbatten, Liaquat offered that he was prepared to ask Junagadh to withdraw its troops from Babariawad and Mangrol on the condition that India disbanded its concentration of troops in Porbandar. When Mountbatten instead urged that a plebiscite be conducted, Liaquat replied that he might consider that ‘if the same general principle was to apply in other cases’ too.[22]

On 19 October, Liaquat again wrote directly to Nehru and referred to his earlier letter. Liaquat repeated his earlier request that India withdraw its troops from Porbandar in exchange for a simultaneous withdrawal of Junagadh's troops from the disputed states of Mangrol and Babariawad, the referral of Mangrol and Babariawad's status to an independent legal counsel to be followed by discussions on a plebiscite. Liaquat also asked India to not occupy any areas from where Junagadh would withdraw its forces.[22]

At the Ministry of States V.P. Menon and C.C. Desai produced a nine-page long memorandum on Junagadh, outlining India's case on Junagadh since before partition and 'fine-tuned' it to justify the impending Indian military action. The memorandum's alarmist and rousing tone caused Mountbatten to enlist Lockhart's help to restrain Patel and Menon. Mountbatten warned Lockhart that Patel and Menon were pushing for Indian forces to enter Babariawad and Mangrol and Mountbatten wanted Lockhart to prepare a military plan so as to stop Junagadh from fighting.[23]

On 21 October 1947 the Defence Committee in its sixth meeting cleared its decks for action in Junagadh. The meeting also discussed the legal status of Mangrol and Babariawad. Monckton and Charles Brunyate, legal advisor of Junagadh, now advised Mountbatten that the legal position in regard to Babariawad was weak and uncertain in the case of Mangrol. Monckton advised that India's case would be better off based on 'the will of the people'.[24]

Patel then took over proceedings and argued that delaying action in Babariaward and Mangrol was causing ‘serious difficulties’.[25] Force was to be used to enable a plebiscite.[26]

Menon ensured that Junagadh’s civil authority would continue in Mangrol and Babariawad even after it withdrew its troops from the two areas.[27]

Meanwhile, Mountbatten stated that if Indian forces were to enter Babariawad they would need to enter in large numbers and with superior equipment so that Junagadh would not consider it worthwhile to resist.[27]