Zulfiqar: Difference between revisions

adding category |

|||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

==Gallery== |

==Gallery== |

||

<gallery> |

<gallery> |

||

Sword and shield reproduction from Bab al Nasr gate Cairo Egypt.jpg|Drawing of [[Fatimid]] version of Zulfiqar in the 10th-century; which is the earliest visual depiction in history, as carved on [[Bab al-Nasr (Cairo)|Bab al-Nasr]], one of the gates of [[Islamic Cairo|Cairo]]. |

|||

COLLECTIE TROPENMUSEUM Katoenen banier met Arabische kalligrafie TMnr 5663-1.jpg|Cotton banner with Arabic calligraph, with the Zulfiqar and Ali represented as a lion (dated to the late 18th or the 19th century), possible Chinese influence. |

COLLECTIE TROPENMUSEUM Katoenen banier met Arabische kalligrafie TMnr 5663-1.jpg|Cotton banner with Arabic calligraph, with the Zulfiqar and Ali represented as a lion (dated to the late 18th or the 19th century), possible Chinese influence. |

||

Shah Jahan and his son, Dara Shikoh, c17th century.jpg|The [[Mughal Empire|Mughal]] Emperor Shah Jahan leading the [[Mughal Army]], in the upper left [[War elephant]]s bear emblems of the legendary Zulfiqar. |

Shah Jahan and his son, Dara Shikoh, c17th century.jpg|The [[Mughal Empire|Mughal]] Emperor Shah Jahan leading the [[Mughal Army]], in the upper left [[War elephant]]s bear emblems of the legendary Zulfiqar. |

||

Revision as of 12:40, 23 September 2017

| Part of a series on |

| Ali |

|---|

|

Zulfiqar (Arabic: ذو الفقار Ḏū-l-Faqār or Ḏū-l-Fiqār) is the name of the legendary sword of Ali ibn Abi Talib which is said to have been given to him by Muhammad. Muhammad gave this sword to his son in law Ali in the Battle of Uhud. The sword was brought by Jibraeel (Gabrial "Lord of Angels") as an order from Allah. It was historically frequently depicted as a scissor-like double bladed sword on Muslim flags, and it is commonly shown in Shi'ite depictions of Ali and in the form of jewelry functioning as talismans as a scimitar terminating in two points. Middle Eastern weapons are commonly inscribed with a quote mentioning Zulfiqar,[1] and Middle Eastern swords are at times made with a split tip in reference to the weapon.[2]

Name

The name is also variously transliterated as Dhulfiqar, Zulfiquar, Zulfikar, Thulfeqar, Zoulfikar, Zulfeqhar etc. The meaning of the name is unclear. The word ذو ḏu means "lord, master", and the idafa construction "master of..." is common in Arabic phraseology (e.g. in Dhu-l-Qarnayn, Dhu-l-Kifl, Dhu-l-Hijjah etc.). The meaning of فقار, on the other hand, is unclear. It may be vocalized as either fiqār or faqār; Lane cites authorities preferring faqār and rejecting fiqār as "vulgar", but the vocalization fiqār still sees the more widespread use. The word faqār has the meaning of "the vertebrae of the back, the bones of the spine, which are set in regular order, one upon another", but may also refer to other instances of regularly spaced rows, specifically it is a name of the stars of the belt of Orion. Interpretations of the sword's name as found in Islamic theological writings or popular piety fall into four categories:[3]

- reference to the literal vertebrae of the spine, yielding an interpretation in the sense of "the severer of the vertebrae; the spine-splitter"

- reference to the stars of the belt of Orion, emphasizing the celestial provenance of the sword

- interpretation of faqār as an unfamiliar plural of fuqrah "notch, groove, indentation", interpreted as a reference to a kind of decoration of regularly spaced notches or dents on the sword

- reference to a "notch" formed by the sword's supposed termination in two points

The latter interpretation gives rise to the popular depiction of the sword as a double-pointed scimitar in modern Shia iconography. Heger (2008) considers two additional possibilities,

- the name in origin referred simply to a double-edged sword (i.e. an actual sword rather than a sabre or scimitar), the μάχαιρα δίστομη of the New Testament

- fiqār is a corruption of firāq "distinction, division", and the name originally referred to the metaphorical sword discerning between right and wrong.

Invocation and depiction

Zulfiqar was frequently depicted on Ottoman flags, especially as used by Janissaries cavalry, in the 16th and 17th centuries. Zulfiqar is also frequently invoked in talismans. A common talismanic inscription or invocation is the double statement (paralleling the tahlila in form):

- لا فتى إلا علي لا سيف إلا ذو الفقار

- [lā fata ʾillā ʿAlī; lā sayf ʾillā Ḏū l-Fiqār.] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)

- "There is no hero like Ali; There is no sword like Dhu-l-Fiqar"

A record of this statement as part of a longer talismanic inscription was published by Tewfik Canaan in The Decipherment of Arabic Talismans (1938).[4]

Legendary background

In legend, the exclamation [lā fata ʾillā ʿAlī lā sayf ʾillā Ḏū l-Fiqār] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) is attributed to Muhammad, who is said to have uttered it in the Battle of Uhud in praise of Aliah's exploit of splitting the shield and helmet of the strongest Meccan warrior, shattering his own sword in the same stroke. Muhammad is said to then have given his own sword Dhu-l-Fiqar to Ali to replace the broken sword. In another variant, the exclamation is not due to Muhammad but to "a voice on the battlefield".[5]

According to the Twelver Shia, Dhū al-Fiqār is currently in the possession of the Imam in occultation Muhammad al-Mahdi, alongside the al-Jafr.[6]

Modern references

In Qajar Iran, actual swords were produced based on the legendary double-pointed design. Thus, Higgins Collection holds a ceremonial sabre with a wootz steel blade, dated to the late 19th century, with a cleft tip. The curator comments that "fractures in the tip were not uncommon in early wootz blades from Arabia" suggesting that the legendary double-pointed design is based on a common type of damage incurred by blades in battle. The tip of this specimen is split in the blade plane, i.e. "For about 8" of its length from the point the blade is vertically divided along its axis, producing side-by-side blades, each of which is finished in itself", in the curator's opinion "a virtuoso achievement by a master craftsman".[7] Another 19th-century blade in the same collection features a split blade as well as saw-tooths along the edge, combining two possible interpretations of the name Dhu-l-Faqar. This blade is likely of Indian workmanship, and it was combined with an older (Mughal era) Indian hilt.[8]

"Zulfiqar" and its phonetic variations has come into use as given name, as with former Pakistani Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

In Iran, the name of the sword has been used as an eponym in military contexts; thus, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi renamed the military order Portrait of the Commander of Faithful to Order of Zolfaghar in 1925.[9] The 58th Takavar Division of Shahroud is also named after the sword. In 2010, Iran revealed an attack boat dubbed the Zolfaghar.[citation needed] An Iranian main battle tank is also named after the sword, Zulfiqar.

During the Bosnian War, a Bosnian army's special unit was named "Zulfikar".

Gallery

-

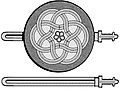

Drawing of Fatimid version of Zulfiqar in the 10th-century; which is the earliest visual depiction in history, as carved on Bab al-Nasr, one of the gates of Cairo.

-

Cotton banner with Arabic calligraph, with the Zulfiqar and Ali represented as a lion (dated to the late 18th or the 19th century), possible Chinese influence.

-

The Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan leading the Mughal Army, in the upper left War elephants bear emblems of the legendary Zulfiqar.

-

Depiction of a kneeling Ali with Zulfiqar on his knees (19th century, MuCEM inv. no. 2003,197,7)

-

An early 19th century Ottoman Zulfiqar flag.

-

A representation of the sword of Ali (Zulfiqar), in the flag of Ahmad Shah Durrani

-

Closeup of the saw-toothed and notched point of the 19th-century Indian-made "Zulfiqar" sword kept in the Higgins Collection (accession no. 2240).

-

Flag of Mahmut Pasha Bushatli (Albania).

-

Coat of Arms of Iran (Pahlavi dynasty) showing a Zulfigar sword.

References

- ^ Gauding, Madonna (October 2009). The Signs and Symbols Bible:The Definitive Guide to Mysterious Markings. Sterling Publishing Company. p. 105.

- ^ Sothebys, none (January 1985). Islamic Works of Art, Carpets and Textiles. Sotheby's, London. p. 438.

- ^ Christoph Heger in: Markus Groß and Karl-Heinz Ohlig (eds.), Schlaglichter: Die beiden ersten islamischen Jahrhunderte, 2008, pp. 278–290.

- ^ reprinted 2004 in Magic and Divination in Early Islam, pp. 125–177, cited after Heger (2008) p. 283. Heger speculates that the talismanic formula may be old and may have originated as a Christian invocation.

- ^ Heger (2008), p. 286.

- ^ Islam, Misbah (30 June 2008). Decline of Muslim States and Societies. Xlibris Corporation. p. 333. ISBN 978-1-4363-1012-3. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

- ^ Higgins Collection, Accession Number 321.a.

- ^ Higgins Collection, Accession Number 2240.

- ^ "Order Of Zolfaghar". Iran Collection. Retrieved 16 January 2013.